Engineering Complexity: Advanced 3D Bioprinting Strategies for Porous, Biomimetic Scaffolds in Regenerative Medicine

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current 3D bioprinting techniques for fabricating porous, biomimetic scaffolds.

Engineering Complexity: Advanced 3D Bioprinting Strategies for Porous, Biomimetic Scaffolds in Regenerative Medicine

Abstract

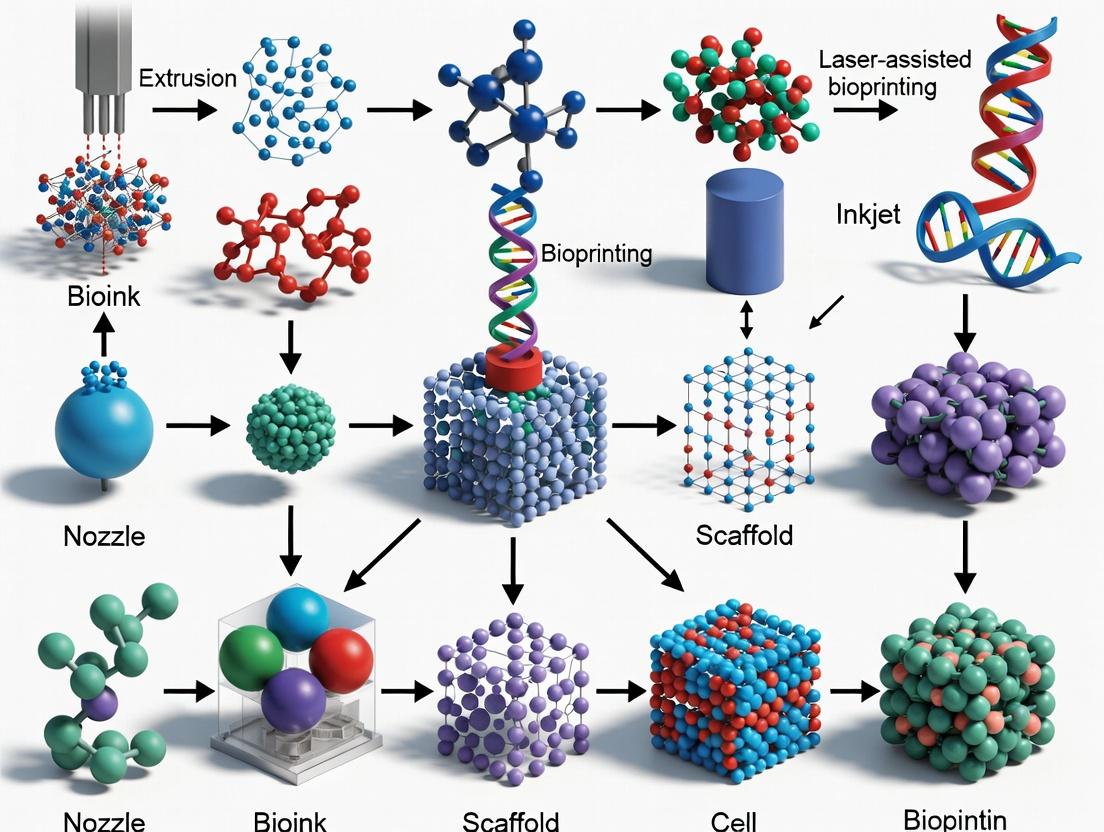

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current 3D bioprinting techniques for fabricating porous, biomimetic scaffolds. It explores the foundational principles of scaffold design, detailing key methodologies such as extrusion-based, inkjet, and light-assisted bioprinting. The content delves into practical applications in tissue engineering and drug screening, addresses common fabrication challenges and optimization strategies, and validates techniques through comparative analysis of structural, mechanical, and biological outcomes. Aimed at researchers and pharmaceutical developers, this review synthesizes cutting-edge advancements to guide the development of next-generation scaffolds for clinical translation.

The Blueprint of Life: Core Principles of Porosity and Biomimicry in Scaffold Design

Within the advancement of 3D bioprinting for porous biomimetic scaffolds, defining the ideal scaffold is paramount. It must transcend being a passive 3D structure and become a bioactive, instructive microenvironment that supports cell viability, proliferation, and specific function. This application note delineates the essential scaffold characteristics—architectural, mechanical, and biochemical—and provides detailed protocols for their quantitative assessment.

Essential Characteristics & Quantitative Data

A scaffold’s performance is governed by a hierarchy of physical and chemical properties. The following table summarizes key metrics and their target ranges for an ideal cell-supportive scaffold.

Table 1: Quantitative Characteristics of an Ideal Biomimetic Scaffold

| Characteristic | Parameter | Ideal Range/Target | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural | Porosity | > 90% | Micro-CT Analysis |

| Pore Size | 100 - 500 μm (cell-type dependent) | SEM Image Analysis | |

| Pore Interconnectivity | > 99% | Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry | |

| Mechanical | Compressive Modulus | 0.1 - 20 kPa (soft tissues) to 10 - 500 MPa (bone) | Uniaxial Compression Test |

| Degradation Rate | Match rate of neo-tissue formation (weeks-months) | Mass Loss in vitro | |

| Surface/Biochemical | Surface Roughness (Ra) | 0.5 - 5 μm | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| Bioactive Molecule Density | 0.1 - 1.0 μg/cm² | Fluorescent Tag Quantification | |

| Biological Performance | Cell Seeding Efficiency | > 85% | DNA Quantification Assay |

| Cell Viability (Day 7) | > 90% | Live/Dead Staining & Confocal | |

| Metabolic Activity (Day 7) | 150-300% of Day 1 Baseline | AlamarBlue/MTT Assay |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessment of Scaffold Porosity and Pore Architecture via Micro-CT Objective: To non-destructively quantify porosity, pore size distribution, and interconnectivity. Materials: µCT scanner (e.g., SkyScan 1272), scaffold sample (dry), image analysis software (CTAn, ImageJ). Procedure:

- Mount the dry scaffold securely on the sample stage.

- Set scan parameters: Voltage=40 kV, Current=250 µA, Pixel Size=5 µm, Rotation Step=0.4°, 180° rotation.

- Perform the scan and reconstruct cross-sectional slices using NRecon software.

- Import reconstructed slices into CTAn. Apply a uniform global threshold to binarize scaffold material from pores.

- Analysis:

- Porosity: Calculate as (Total Volume - Material Volume) / Total Volume.

- Pore Size Distribution: Execute the "Sphere Fitting" algorithm.

- Interconnectivity: Use the "Analyze Particles" function on a binarized inverse image; interconnectivity = (volume of connected pores / total pore volume) x 100%.

- Generate 3D models for visualization.

Protocol 2: Evaluation of Cell Viability, Distribution, and Metabolic Activity Objective: To assess the cytocompatibility and bioactivity of the scaffold over time. Materials: Seeded scaffold, PBS, Calcein-AM (4 µM) and Ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1, 2 µM) in PBS, AlamarBlue reagent, Confocal microscope, Plate reader. Procedure: Part A: Live/Dead Staining & Confocal Microscopy

- At designated time points (Days 1, 3, 7), aspirate culture medium.

- Rinse scaffold gently with warm PBS.

- Incubate with Live/Dead staining solution (Calcein-AM/ EthD-1) for 45 minutes at 37°C, protected from light.

- Rinse with PBS and image immediately using a confocal microscope (z-stack 50 µm deep). Calculate viability as: (Live cells / (Live+Dead cells)) x 100%. Part B: Metabolic Activity (AlamarBlue Assay)

- Prepare a 10% (v/v) solution of AlamarBlue reagent in fresh culture medium.

- After Live/Dead imaging, transfer scaffolds to a new plate, add the 10% reagent solution, and incubate for 3 hours at 37°C.

- Transfer 100 µL of the reacted supernatant to a 96-well plate.

- Measure fluorescence (Ex 560 nm / Em 590 nm) on a plate reader. Express data as percentage relative to Day 1 control scaffolds.

Protocol 3: Functional Assessment of Osteogenic Differentiation in a Bone Scaffold Objective: To quantify scaffold-induced osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). Materials: hMSC-seeded scaffold, Osteogenic medium (OM: DMEM, 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 µM ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, 100 nM dexamethasone), ALP staining kit, Quantification buffer (pNPP), qPCR reagents for RUNX2, OSP. Procedure:

- Culture hMSC-seeded scaffolds in OM for 7, 14, and 21 days.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity (Day 7/14):

- Lyse cells in 0.1% Triton X-100.

- Mix lysate with pNPP substrate, incubate 30 min, stop with 1N NaOH.

- Measure absorbance at 405 nm. Normalize to total DNA content.

- Gene Expression Analysis (Day 14/21):

- Extract total RNA, synthesize cDNA.

- Perform qPCR for osteogenic markers (RUNX2, OSP) and housekeeping gene (GAPDH). Calculate fold change using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method.

Signaling Pathway: Integrin-Mediated Cell Adhesion on a Functionalized Scaffold

Title: RGD-Integrin Signaling to Cell Functions

Workflow: Bioprinting and Evaluating a Biomimetic Scaffold

Title: Bioprinted Scaffold Fabrication and Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Scaffold Biofabrication and Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photo-crosslinkable bioink providing natural cell-adhesion motifs (RGD). | Tuneable mechanical properties via degree of substitution and concentration. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA) | Synthetic, bio-inert hydrogel precursor for controlled mechanical and biochemical functionalization. | Serves as a blank slate for covalent attachment of peptides. |

| RGD Peptide Solution | Synthetic Arg-Gly-Asp peptides to functionalize synthetic scaffolds for integrin-mediated cell adhesion. | Commonly used at 0.5-2.0 mM concentration for coupling. |

| AlamarBlue Cell Viability Reagent | Resazurin-based, non-toxic assay for quantifying metabolic activity over time in the same sample. | Allows longitudinal tracking. |

| Calcein-AM / EthD-1 Live/Dead Kit | Two-color fluorescence assay for simultaneous determination of live (green) and dead (red) cells in 3D constructs. | Critical for confocal z-stack viability assessment. |

| Triton X-100 Solution (0.1%) | Non-ionic detergent for cell lysis to release intracellular enzymes (e.g., ALP) for quantitative biochemical assays. | |

| p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate (pNPP) | Colorimetric substrate for Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), turning yellow upon cleavage, measured at 405 nm. | Standard for early osteogenic marker detection. |

| Osteogenic Induction Cocktail | Defined supplement (Dexamethasone, β-Glycerophosphate, Ascorbate) to direct hMSCs toward bone lineage. | Essential for functional differentiation assays. |

Application Notes

Within the field of 3D bioprinting for biomimetic scaffolds, porosity is not merely the presence of voids but a critical architectural determinant of biological function. The triad of interconnectivity, pore size, and diffusive transport dictates the ultimate success of a scaffold in supporting cell viability, tissue ingrowth, and functional maturation. This is paramount for applications in regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug screening.

- Interconnectivity: Refers to the degree to which pores are linked, forming a continuous network. It is the non-negotiable enabler for cell migration, vascularization, and uniform tissue formation. Scaffolds with high porosity but low interconnectivity act as isolated chambers, leading to necrotic cores.

- Pore Size: Governs specific cellular behaviors. While optimal sizes are cell-type and tissue-dependent, general ranges are established: <50µm for neovascularization, 50-150µm for osteogenesis, 100-350µm for bone ingrowth, and 200-500µm for chondrogenesis and hepatocyte function.

- Nutrient/Waste Diffusion: In the avascular phase post-implantation, survival depends on passive diffusion. The effective diffusion coefficient (Deff) within a porous scaffold is a function of its tortuosity (τ) and porosity (ε): Deff = (ε/τ) * D. This makes interconnectivity a direct regulator of metabolic waste clearance and nutrient supply, preventing central necrosis.

The design challenge in 3D bioprinting is to precisely engineer this porous architecture concurrently with the deposition of bioinks. Techniques like sacrificial bioprinting, cryogenic printing, and the tuning of printing parameters (pressure, speed, infill pattern) are leveraged to achieve target porosity profiles.

Table 1: Optimal Pore Size Ranges for Tissue-Specific Scaffolds

| Tissue Target | Optimal Pore Size Range (µm) | Primary Cellular/Physiological Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Regeneration | 300 - 500 | Facilitates osteoconduction, vascular invasion, and bone matrix deposition. |

| Cartilage Tissue | 200 - 350 | Supports chondrocyte migration and ECM production, while maintaining structural integrity. |

| Skin Regeneration | 80 - 150 | Promotes fibroblast infiltration, keratinocyte migration, and rapid neovascularization. |

| Neural Tissue | 50 - 120 | Guides neurite extension and supports glial cell integration. |

| Hepatocyte Culture | 200 - 500 | Enhances oxygenation and mass transfer for high-density, metabolically active cells. |

| Vascular Ingrowth | > 50 (interconnected) | Minimum size required for endothelial cell sprouting and capillary formation. |

Table 2: Impact of Porosity & Interconnectivity on Diffusion Efficiency

| Scaffold Material | Total Porosity (ε) % | Interconnectivity (%) | Measured D_eff / D (Glucose) | Key Outcome (In Vitro/In Vivo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Printed PCL (Honeycomb) | 70 | ~100 | 0.68 | Uniform cell distribution; no central necrosis after 14 days. |

| Salt-Leached PLGA | 85 | 75 | 0.45 | Viable periphery, necrotic core (>500µm depth) observed. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | 90 (Cryogel) | >95 | 0.82 | Superior cell viability (>95%) throughout 1.5mm thick construct. |

| Silk Fibroin (Freeze-dried) | 92 | 60 | 0.32 | Limited cell infiltration; viability restricted to <200µm surface layer. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Scaffold Interconnectivity via Micro-CT Analysis

Objective: To non-destructively calculate the percentage of interconnected porosity within a 3D-bioprinted scaffold. Materials: Micro-CT scanner (e.g., SkyScan 1272), 3D-bioprinted scaffold sample (dry), image analysis software (CTAn, Fiji/ImageJ), computer. Procedure:

- Sample Mounting: Secure the dry scaffold on the sample holder using low-density foam to prevent movement.

- Scanning Parameters: Set isotropic voxel size to 1/3 of the target minimum pore diameter. Use a rotation step of 0.4° over 180°. Apply a 0.5mm aluminum filter if using a polymer scaffold to reduce beam hardening.

- Image Reconstruction: Use the scanner's proprietary software (NRecon for SkyScan) to reconstruct cross-sectional images. Apply consistent beam hardening and ring artifact correction.

- Binarization (CTAn):

- Load the image stack. Define a global threshold using the Otsu method to separate solid material from pore space.

- Apply a despeckle function to remove noise.

- 3D Analysis:

- Select the region of interest (ROI) encompassing the entire scaffold.

- Execute "Analysis -> 3D Analysis." The key output is "Open Porosity %," which represents the interconnected pore volume as a percentage of total scaffold volume. The "Closed Porosity %" represents isolated pores.

- Visualization: Use CTVox or Fiji's 3D Viewer to generate 3D models of the interconnected pore network.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Nutrient Diffusion and Cell Viability in Thick Scaffolds

Objective: To correlate scaffold porosity parameters with gradients in cell viability driven by diffusion limits. Materials: 3D-bioprinted cell-laden scaffold (e.g., with mesenchymal stem cells), live/dead viability/cytotoxicity kit (Calcein AM/EthD-1), confocal microscope, image analysis software (e.g., Imaris, Fiji). Procedure:

- Scaffold Culture: Culture a thick (>2mm) cell-laden scaffold in standard medium for 3-7 days under static conditions to establish diffusion-driven gradients.

- Staining:

- Prepare staining solution per manufacturer's protocol (e.g., 2µM Calcein AM, 4µM Ethidium homodimer-1 in PBS).

- Rinse scaffold with PBS. Incubate in staining solution for 45-60 minutes at 37°C, protected from light.

- Imaging:

- Rinse and image the scaffold immediately. Using a confocal microscope, acquire Z-stacks from the top surface to the center of the scaffold. Use 10x or 20x objective.

- Set excitation/emission for Calcein (494/517 nm, green) and EthD-1 (528/617 nm, red).

- Quantitative Analysis (Fiji):

- Split channels. For each Z-slice (representing a depth), threshold the green (live) and red (dead) channels separately.

- Measure the area fraction of live and dead signal for each slice.

- Plot % Live Cells vs. Depth (µm).

- Correlation: Compare the depth at which viability drops below 70% with the scaffold's measured interconnectivity and average pore size from Protocol 1. High-interconnectivity scaffolds will maintain viability to greater depths.

Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Porosity & Diffusion Studies

| Item | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Sacrificial Bioink (e.g., Pluronic F-127, Gelatin) | Printed as a temporary lattice to create interconnected channels, which are later liquefied and removed. | Must be cytocompatible during printing and dissolve under mild conditions (e.g., cooling, enzymatic digestion). |

| Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) System | Provides non-destructive 3D quantification of total porosity, pore size distribution, and interconnectivity. | Resolution must be significantly higher than the feature size of interest (e.g., <5µm voxel for 50µm pores). |

| Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit | Dual-fluorescence stain (Calcein AM for live, EthD-1 for dead cells) to map viability gradients within scaffolds. | Requires penetration through the scaffold matrix; incubation times may need optimization for dense constructs. |

| Mathematical Diffusion Models (e.g., Fick's Law, COMSOL) | Used to predict nutrient/waste concentration gradients and D_eff based on scaffold architecture pre-experiment. | Input parameters (ε, τ) must be derived from accurate structural data (e.g., Micro-CT). |

| Tunable Hydrogel (e.g., GelMA, Alginate) | Base bioink material whose crosslinking density can be modulated to intrinsically alter matrix porosity and diffusivity. | Polymer concentration, degree of methacrylation, and UV crosslinking time are critical control parameters. |

| Perfusion Bioreactor System | Applied post-printing to overcome diffusion limits, allowing culture of large, dense constructs. Validates the importance of designed porosity. | Flow rates must be optimized to provide shear stress conducive to the target cell type without causing detachment. |

Within the broader thesis on 3D bioprinting techniques for porous biomimetic scaffolds, replicating native tissue ECM architecture is paramount. The ECM is not a passive scaffold but a dynamic, instructive niche that regulates cellular adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and mechanotransduction. Biomimicry of the ECM involves recapitulating its biochemical composition, hierarchical architecture (from nano- to microscale), mechanical properties, and spatiotemporal signaling. This document provides application notes and protocols for analyzing native ECM and fabricating biomimetic scaffolds via advanced 3D bioprinting.

Quantitative Analysis of Native ECM Architecture

Understanding native ECM parameters is the first critical step. Below are summarized metrics for key tissues, guiding scaffold design targets.

Table 1: Architectural and Mechanical Properties of Native Tissue ECM

| Tissue Type | Average Fiber Diameter (nm) | Pore Size Range (μm) | Porosity (%) | Elastic Modulus (kPa) | Predominant ECM Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin (Dermis) | 50 - 150 | 50 - 200 | 75 - 90 | 2 - 80 | Collagen I/III, Elastin, HA, Fibronectin |

| Bone (Trabecular) | 500 - 2000 (fibril bundle) | 200 - 600 | 50 - 90 | 10,000 - 20,000 | Collagen I, Hydroxyapatite |

| Articular Cartilage | 20 - 80 | 30 - 100 | 60 - 85 | 500 - 1000 | Collagen II, Aggrecan, HA |

| Liver | 40 - 100 | 10 - 50 | 20 - 40 | 0.5 - 1.5 | Collagen I/III/IV, Laminin, Fibronectin |

| Cardiac Muscle | 80 - 200 | 50 - 150 | 70 - 80 | 10 - 50 | Collagen I/IV, Laminin, Fibronectin |

| Peripheral Nerve | 50 - 100 (basal lamina) | 5 - 20 (conduit) | 60 - 80 | 0.5 - 1.0 | Collagen IV, Laminin, Fibronectin |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Decellularized ECM (dECM) Hydrogel Preparation for Bioink Formulation

Objective: To create a bioactive bioink derived from tissue-specific ECM. Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit, Section 5.0. Procedure:

- Tissue Acquisition & Processing: Mince 1g of porcine or human source tissue (e.g., skin, heart) into <1 mm³ pieces. Rinse in PBS with 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic.

- Decellularization: Treat tissue with:

- 0.1% SDS for 48h (agitation at 4°C) to lyse cells and solubilize cytoplasmic components.

- Rinse with PBS until no SDS is detectable (conductivity measurement).

- Treat with 1% Triton X-100 for 24h (agitation, RT) to remove nuclear remnants.

- Rinse with nuclease-free water (72h, with changes) to remove detergents.

- Lyophilization & Milling: Freeze at -80°C, lyophilize for 48h. Pulverize into a fine powder using a cryomill.

- Digestion & pH Neutralization: Digest dECM powder in 0.5M acetic acid with 1 mg/mL pepsin (w/v) for 48-72h at 4°C (constant stirring). Maintain a 1:100 (w/v) ratio. Neutralize to pH 7.4 using 1M NaOH and dilute with 10x PBS to achieve isotonicity.

- Sterilization & Storage: Filter sterilize (0.22 μm) under vacuum. Store at 4°C for up to 1 week. For long-term storage, aliquot and freeze at -80°C.

Protocol 3.2: Multi-Material 3D Bioprinting of a Zonal Cartilage-Mimetic Scaffold

Objective: To fabricate a scaffold mimicking the depth-dependent collagen architecture of articular cartilage. Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit, Section 5.0. Procedure:

- Bioink Preparation:

- Superficial Zone Ink: 8% (w/v) Methacrylated Silk Fibroin (SilMA), 2% (w/v) Methacrylated Hyaluronic Acid (HAMA), 0.1% LAP photoinitiator. Mix with primary chondrocytes at 20x10⁶ cells/mL.

- Deep Zone Ink: 4% (w/v) SilMA, 4% (w/v) Methacrylated Chondroitin Sulfate (CSMA), 0.1% LAP. Mix with chondrocytes at 10x10⁶ cells/mL.

- Printing Parameters (Extrusion-based, dual-head):

- Nozzle Diameter: 250 μm.

- Pressure: 20-25 kPa (Superficial), 15-20 kPa (Deep).

- Print Speed: 8 mm/s.

- Print Bed Temp: 15°C.

- Layer-by-Layer Fabrication:

- Program a 0/90° filament pattern for each layer.

- Print 10 layers of Superficial Zone Ink (final height ~500 μm).

- Without interrupting the print, switch to Deep Zone Ink.

- Print subsequent 40 layers (final scaffold height ~2.5 mm).

- Crosslinking: Immediately after printing, expose the entire construct to 405 nm light at 15 mW/cm² for 60 seconds per side. Incubate in chondrogenic medium (with TGF-β3) at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

Key Signaling Pathways in ECM-Biomimetic Scaffold Interaction

Diagram 1: Key Mechanotransduction Pathways from Biomimetic ECM

Diagram 2: Workflow for Biomimetic ECM Scaffold Development

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for ECM Biomimicry and 3D Bioprinting

| Item Name / Catalog Example | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Methacrylated Gelatin (GelMA) | Bioink Polymer | Provides RGD motifs for cell adhesion and tunable photocrosslinkability for soft tissue mimics. |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) Powder | Bioink Additive | Preserves tissue-specific biochemical cues (collagens, GAGs, growth factors). |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-Trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Photoinitiator | Enables rapid, cytocompatible visible light (405 nm) crosslinking of methacrylated bioinks. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Detergent | Primary agent for decellularization; lyses cells and solubilizes cytoplasmic components. |

| Triton X-100 | Detergent | Non-ionic surfactant used to remove nuclear remnants and lipids after SDS treatment. |

| Recombinant Human TGF-β3 | Growth Factor | Induces chondrogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage scaffolds. |

| Integrin α5β1 Inhibitor (ATN-161) | Signaling Modulator | Validates the specific role of fibronectin-integrin interactions in cell-scaffold responses. |

| AlamarBlue / CellTiter-Glo | Viability Assay | Quantifies metabolic activity and proliferation of cells within 3D printed constructs. |

| Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDFs) or Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Cell Source | Standardized primary cells for evaluating scaffold biocompatibility and bioactivity. |

| Advanced Rheometer (e.g., TA Instruments) | Equipment | Characterizes bioink viscoelastic properties (storage/loss modulus) to optimize printability. |

Application Notes and Protocols

Thesis Context: Within the research on 3D bioprinting techniques for porous biomimetic scaffolds, the selection and formulation of the biomaterial ink (bioink) is critical. These scaffolds must mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM), provide structural integrity, support cell viability, and guide tissue regeneration. This document details the application and processing protocols for key biomaterial classes.

Hydrogel-Based Bioinks: Crosslinking Protocols

Hydrogels form the foundational aqueous environment for cell encapsulation. Their crosslinking method dictates printability, mechanical properties, and gelation kinetics.

Protocol 1.1: Dual-Crosslinking of Alginate-Gelatin (Alg-Gel) Composite Bioink

Objective: To create a shape-fidelity stable, cell-laden construct using ionic and thermal crosslinking. Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit," Table 2. Workflow:

- Bioink Preparation: Sterilize sodium alginate (4% w/v) and gelatin (8% w/v) in DPBS separately at 60°C. Mix in a 1:1 ratio under sterile conditions. Cool to 37°C and mix with cell suspension to a final density of 1-5 x 10^6 cells/mL.

- Printing & Primary Crosslink: Bioprint the Alg-Gel/cell mixture into a pre-cooled (4°C) printing bed. The rapid thermal gelation of gelatin provides initial shape fidelity.

- Secondary Crosslink: Immerse the printed construct in a sterile 100 mM CaCl₂ solution for 5-10 minutes. Ca²⁺ ions ionically crosslink the alginate chains, providing long-term stability.

- Culture: Rinse with culture medium and transfer to an incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂). Gelatin gradually solubilizes, increasing scaffold porosity and leaving behind a stable alginate network.

Diagram: Dual-Crosslinking Workflow for Alg-Gel Bioink

Table 1: Crosslinking Methods for Common Hydrogel Bioinks

| Hydrogel | Crosslinking Mechanism | Key Agent/Stimulus | Gelation Time | Key Property |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | Ionic | Ca²⁺, Ba²⁺ ions | Seconds-Minutes | Rapid, reversible |

| GelMA | Photo-chemical | UV/VIS light (LAP photoinitiator) | < 60 seconds | Spatiotemporal control |

| Fibrin | Enzymatic | Thrombin + Ca²⁺ | Seconds | Natural cell adhesion |

| PEGDA | Photo-chemical | UV light | Seconds | Highly tunable mechanics |

| Collagen I | Thermal/pH | Temperature shift to 37°C, pH 7.4 | Minutes | Native ECM composition |

Ceramic Bioinks: Printing and Sintering for Bone Scaffolds

Ceramics like hydroxyapatite (HA) and tricalcium phosphate (TCP) are essential for osteoconductive bone scaffolds but require dispersion in a carrier hydrogel for printability.

Protocol 2.1: Direct Ink Writing (DIW) of α-TCP/Pluronic F127 Composite Paste Objective: To fabricate a macro-porous ceramic green body for subsequent sintering into a pure bioceramic scaffold. Materials: α-TCP powder (≤ 50 µm), Pluronic F127, deionized water, 3D bioprinter with pneumatic syringe extruder, high-temperature furnace. Workflow:

- Paste Synthesis: Create a 30% w/v Pluronic F127 solution in cold water. Gradually blend in α-TCP powder to a final ceramic loading of 40-50% w/w. Homogenize under vacuum to remove air bubbles.

- Printing: Load paste into a syringe. Print at 4-10°C (to keep Pluronic viscous) through a tapered nozzle (400-610 µm). Apply constant pressure (25-40 psi) for steady extrusion.

- Post-Processing: Air-dry the printed "green body" for 24h. Sinter in a furnace with a controlled ramp (1-5°C/min to 1100-1300°C, hold for 2h, cool slowly). Pluronic burns off, leaving a densified, micro-porous α-TCP scaffold.

Table 2: Sintering Parameters for Ceramic Bioinks

| Ceramic Type | Sintering Temp. Range | Hold Time | Final Porosity | Compressive Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) | 1100 - 1150°C | 2-3 hours | 40-60% | 10-20 MPa |

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) | 1200 - 1300°C | 2-4 hours | 30-50% | 20-50 MPa |

| Bioactive Glass (4555) | 600 - 700°C | 1 hour | 50-70% | 5-15 MPa |

Composite Bioink Protocol: Reinforced GelMA with Nanocellulose

Protocol 3.1: Formulating a Nanocomposite Bioink for Meniscus Tissue Engineering Objective: To enhance the mechanical resilience of a soft, cell-laden hydrogel for load-bearing soft tissue applications. Materials: GelMA (5-10% w/v), Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) photoinitiator (0.25% w/v), TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibrils (CNF, 0.5-1.5% w/v), chondrocytes. Workflow:

- CNF Dispersion: Sonicate CNF suspension in PBS (1% w/v) for even dispersion.

- Bioink Formulation: Dissolve GelMA and LAP in warm PBS (40°C). Cool to room temp, then mix with the CNF dispersion and cell suspension. Final concentrations: 7.5% GelMA, 0.25% LAP, 1% CNF, 5x10^6 cells/mL.

- Printing & Crosslinking: Extrude bioink into a lattice structure. Immediately expose to 405 nm visible light (5-10 mW/cm²) for 60-90 seconds per layer for full photocrosslinking.

- Mechanical Assessment: Perform rheology (storage modulus G') and cyclical compression testing to quantify reinforcement.

Diagram: CNF-Reinforced GelMA Composite Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Bioink Development and Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photo-crosslinkable hydrogel providing natural RGD motifs for cell adhesion. | Advanced BioMatrix, ESI-BIO |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Cytocompatible, visible-light photoinitiator for rapid crosslinking of GelMA/PEGDA. | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI Chemicals |

| Alginic Acid (Sodium Salt) | Polysaccharide for ionic crosslinking; provides shear-thinning behavior. | NovaMatrix, Sigma-Aldrich |

| β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) Powder | Osteoconductive ceramic for bone scaffold bioinks. | Sigma-Aldrich, Berkeley Advanced Biomaterials |

| TEMPO-Oxidized Nanocellulose | Nanofibrillar additive to enhance bioink viscosity, stiffness, and shape fidelity. | CelluForce, University of Maine Process Center |

| Pluronic F127 | Thermoreversible sacrificial polymer for ceramic paste printing. | Sigma-Aldrich, BASF |

| Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) | Multipotent primary cells for evaluating osteogenic/chondrogenic differentiation in scaffolds. | Lonza, ATCC |

| Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit | Fluorescent assay (Calcein AM/EthD-1) to quantify cell viability post-printing. | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

The success of 3D bioprinted porous biomimetic scaffolds in tissue engineering hinges on the recapitulation of native biological imperatives. This involves the precise spatial and temporal incorporation of three core components: (1) living cells as building blocks, (2) growth factors (GFs) as biochemical messengers, and (3) physical/chemical signaling cues from the scaffold matrix. The convergence of these elements within a porous 3D architecture directs cell fate—including adhesion, proliferation, migration, and differentiation—toward functional tissue formation. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this integration is critical for developing advanced in vitro disease models, high-throughput drug screening platforms, and clinically viable implants.

Key Application Notes:

- Spatial Patterning: Multi-material bioprinting allows the codeposition of different cell types and bioinks laden with specific GFs into distinct zones of a scaffold, mimicking tissue interfaces (e.g., osteochondral tissue).

- Temporal Control: GF release kinetics can be engineered via encapsulation in microparticles (e.g., gelatin, PLGA) or by leveraging enzyme-sensitive or shear-thinning bioinks to provide staged signaling crucial for complex morphogenesis.

- Mechanotransduction: Scaffold porosity, stiffness (elastic modulus), and microtopography are physical cues that interact with integrin-mediated signaling pathways, influencing stem cell lineage commitment. A pore size of 100-300 µm is often optimal for cell infiltration and vascularization.

- Drug Screening: Bioprinted tumor models incorporating patient-derived cells, relevant ECM components, and gradient-forming GF cues provide more predictive platforms for oncology drug efficacy and toxicity testing compared to 2D cultures.

Table 1: Common Growth Factors & Their Roles in 3D Bioprinted Scaffolds

| Growth Factor | Abbreviation | Typical Concentration Range in Bioinks | Primary Cellular Target | Key Function in 3D Scaffolds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor | VEGF | 10-100 ng/mL | Endothelial Cells, Progenitors | Promotes angiogenesis; critical for vascularization of thick constructs. |

| Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 | BMP-2 | 50-200 ng/mL | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Osteoprogenitors | Induces osteogenic differentiation; enhances bone regeneration. |

| Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor | bFGF/FGF-2 | 5-50 ng/mL | MSCs, Chondrocytes, Fibroblasts | Promotes cell proliferation, chondrogenesis, and maintains stemness. |

| Transforming Growth Factor-beta 3 | TGF-β3 | 10-50 ng/mL | MSCs, Chondrocytes | Potent inducer of chondrogenic differentiation; stimulates ECM production. |

| Nerve Growth Factor | NGF | 50-100 ng/mL | Neurons, PC12 Cells | Supports neuronal outgrowth, guidance, and survival in neural scaffolds. |

Table 2: Impact of Scaffold Physical Cues on Cell Behavior

| Scaffold Parameter | Typical Target Range | Key Signaling Pathways Influenced | Cellular Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Pore Size | 100-300 µm (bone), 150-500 µm (soft tissue) | Integrin/FAK, YAP/TAZ | Cell infiltration, nutrient diffusion, neo-tissue formation. |

| Elastic Modulus (Stiffness) | ~0.1-1 kPa (brain), ~8-15 kPa (muscle), ~25-40 kPa (bone) | Rho/ROCK, YAP/TAZ, MKL/SRF | Stem cell lineage specification (soft->neuro/adirogenic, stiff->osteogenic). |

| Fiber Diameter (Nanofibrous) | 50-500 nm | Integrin clustering, Wnt/β-catenin | Enhanced cell adhesion, spreading, and differentiation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bioprinting a VEGF-Gradient Scaffold for Angiogenesis Studies Aim: To fabricate a gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA)-based scaffold with a spatially defined VEGF gradient to direct endothelial cell network formation.

Materials:

- Cells: Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs).

- Bioink A: 7% (w/v) GelMA, 0.25% photoinitiator (LAP), HUVECs (5x10^6 cells/mL) in cell culture medium.

- Bioink B: 7% (w/v) GelMA, 0.25% LAP, HUVECs (5x10^6 cells/mL), VEGF (50 ng/mL) in medium.

- Bioprinter: Extrusion-based with dual-printhead and UV crosslinking module.

- Software: Slicer capable of generating gradient infill patterns.

Method:

- Preparation: Sterilize printer stage and printheads. Maintain cells and bioinks on ice.

- Bioink Loading: Load Bioink A into printhead 1 and Bioink B into printhead 2.

- Gradient Design: Using the slicer software, design a rectangular construct (10x10x2 mm). Set the infill pattern to a linear gradient from 100% Bioink A (left) to 100% Bioink B (right).

- Printing Parameters: Set nozzle diameter (27G), pressure (20-30 kPa), printing speed (5 mm/s), and layer height (150 µm). Stage temperature: 15°C.

- Bioprinting: Print the construct layer-by-layer. After each layer, apply UV light (365 nm, 5 mW/cm²) for 30 seconds for partial crosslinking.

- Final Crosslinking: Post-print, irradiate the entire construct with UV light (365 nm, 5 mW/cm²) for 2 minutes.

- Culture: Transfer to endothelial cell growth medium (without VEGF) and culture for up to 14 days. Analyze network formation (total tube length, junctions) via fluorescence microscopy on days 3, 7, and 14.

Protocol 2: Assessing Osteogenic Differentiation in BMP-2 Loaded, Bioprinted Scaffolds Aim: To evaluate the osteo-inductive capacity of a BMP-2-releasing, alginate/hydroxyapatite bioink on encapsulated MSCs.

Materials:

- Cells: Human Bone Marrow-derived MSCs (passage 3-5).

- Bioink: 3% (w/v) alginate, 2% (w/v) nano-hydroxyapatite, 5x10^6 MSCs/mL, BMP-2 (100 ng/mL).

- Crosslinker: 100 mM CaCl₂ solution.

- Control: Bioink without BMP-2.

Method:

- Scaffold Fabrication: Extrude bioink into a grid structure (15x15x3 mm) directly into a CaCl₂ bath for 10 minutes for ionic crosslinking. Wash with PBS.

- Culture: Maintain scaffolds in basic osteogenic medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep) without dexamethasone or β-glycerophosphate to isolate BMP-2 effect. Change media every 3 days.

- Analysis (Day 21):

- Gene Expression (qRT-PCR): Lyse cells, extract RNA, and analyze markers: Runx2 (early), Osteocalcin (OCN) (late). Normalize to GAPDH.

- Protein Detection (Immunofluorescence): Fix scaffolds, permeabilize, stain for OCN (primary anti-OCN, secondary Alexa Fluor 488), and DAPI for nuclei. Image via confocal microscopy.

- Biochemical Assay (Quantitative): Perform Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity assay on cell lysates using pNPP substrate. Normalize to total protein content (BCA assay).

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Key Signaling Pathways in a 3D Bioprinted Scaffold

Diagram 2: Workflow for a Functionalized Bioink Experiment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Incorporating Biological Imperatives

| Item | Function in 3D Bioprinting Research | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Photo-crosslinkable Hydrogels | Provide a biocompatible, printable matrix that can be stabilized via light, enabling high-fidelity 3D structures. | Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA), Poly(ethylene glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA). |

| Integrin-Binding Peptides | Graft onto inert polymers to provide essential cell adhesion signaling (e.g., via RGD sequence). | RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) peptide, IKVAV peptide for neural cells. |

| Growth Factor Carriers | Protect GFs from denaturation and control their release kinetics from the scaffold over time. | Gelatin microparticles, Heparin-based coacervates, PLGA nanoparticles. |

| Mechano-sensitive Reporters | Tools to visualize and quantify cellular response to scaffold physical properties. | FRET-based tension biosensors (e.g., Vinculin-FRET), YAP/TAZ localization antibodies. |

| Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay Kits | Standardized methods to assess cell health post-printing in 3D. | Live/Dead (Calcein AM/EthD-1) assay, AlamarBlue/Resazurin metabolic assay. |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) Bioinks | Provide a complex, tissue-specific cocktail of native structural proteins and signaling molecules. | Cardiac dECM, Liver dECM, Adipose dECM powders. |

From Digital Model to Living Construct: A Guide to Primary 3D Bioprinting Techniques

Within the broader thesis on 3D bioprinting techniques for fabricating porous biomimetic scaffolds, extrusion-based bioprinting (EBB) stands out as the predominant and versatile workhorse. Its significance lies in its unique capacity to handle high-viscosity, cell-laden bioinks, enabling the fabrication of high-cell-density constructs essential for tissue engineering and drug development. This application note details protocols and data central to leveraging EBB for creating biomimetic, cell-rich porous structures.

Key Advantages and Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes the core capabilities of EBB that make it ideal for high-cell-density applications.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Extrusion-Based Bioprinting for High-Cell-Density Constructs

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Significance for High-Cell-Density Constructs |

|---|---|---|

| Bioink Viscosity | 30 mPa·s to > 6 x 10⁷ mPa·s | Enables incorporation of high cell densities (10⁶ – 10⁸ cells/mL) without rapid sedimentation. |

| Cell Viability (Post-Printing) | 40% – 95% (Protocol Dependent) | Direct function of shear stress management; target is >80% for functional constructs. |

| Printing Resolution | 50 µm – 1 mm | Suitable for creating porous networks (100-500 µm pores) that mimic native tissue vasculature. |

| Printing Speed | 1 – 50 mm/s | Balances throughput with shear stress exposure time. |

| Maximum Cell Density | Up to 1 x 10⁸ cells/mL | Facilitates fabrication of tissue-like cellularity, crucial for organotypic models and tissue repair. |

| Common Gelation Method | Thermal, Ionic, Photocrosslinking | Provides structural integrity to the soft, cell-dense filament post-deposition. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bioink Preparation & Rheological Characterization for High Cell Density

Aim: To formulate and characterize a shear-thinning bioink capable of supporting high cell density.

Materials:

- Primary cells or cell line (e.g., NIH/3T3, hMSCs)

- Base hydrogel (e.g., Alginate, GelMA, Collagen, Fibrin)

- Crosslinker (e.g., CaCl₂ for alginate, photoinitiator for GelMA)

- Cell culture medium (appropriate for cell type)

- Sterile centrifuge tubes, pipettes, biosafety cabinet

Method:

- Cell Harvesting: Culture cells to ~80% confluence. Trypsinize, quench, and centrifuge. Count cells using a hemocytometer.

- Bioink Mixing: Prepare sterile hydrogel precursor solution. Gently resuspend the cell pellet in the precursor solution to achieve the target final density (e.g., 5 x 10⁶ to 5 x 10⁷ cells/mL). Mix by slow pipetting to minimize air bubbles and shear stress. Keep on ice for temperature-sensitive materials (e.g., collagen).

- Rheology:

- Load bioink onto a parallel-plate rheometer.

- Perform a shear rate sweep (e.g., 0.1 to 100 s⁻¹) at printing temperature to confirm shear-thinning behavior.

- Perform an amplitude sweep to determine the linear viscoelastic region and gelation time if applicable.

- Key Metric: Ensure viscosity at high shear (∼10-100 s⁻¹, simulating nozzle flow) is low enough for extrusion, and at low shear (∼0.1 s⁻¹, post-deposition) is high enough to hold shape.

Protocol 2: Optimized Extrusion Bioprinting of High-Density Constructs

Aim: To print a porous, high-cell-density scaffold with maintained cell viability.

Materials:

- Prepared cell-laden bioink

- Extrusion bioprinter (pneumatic or piston-driven)

- Sterile printing cartridge and nozzles (diameter: 22G-27G)

- Sterile, crosslinking-compatible substrate (e.g., Petri dish, transwell)

- Crosslinking apparatus (e.g., UV lamp for GelMA, CaCl₂ mist for alginate)

Method:

- Printer Setup: Sterilize all fluid-path components (nozzle, cartridge) with 70% ethanol and UV light. Load the bioink into the cartridge, avoiding bubbles. Mount cartridge and nozzle.

- Print Parameter Calibration:

- Set printing temperature (e.g., 4°C for collagen, 20-37°C for others).

- Calibrate pressure (pneumatic) or plunger speed (piston) using a dummy bioink of similar viscosity to achieve a consistent filament flow.

- Critical Optimization: Perform a test print grid, varying pressure and speed. Measure filament diameter. Select parameters where extruded filament diameter matches nozzle inner diameter ± 10%.

- Scaffold Printing:

- Design a porous scaffold (e.g., 0/90° grid) with 300-500 µm pore size using slicing software.

- Initiate print. For materials requiring immediate gelation (e.g., alginate), use a co-axial nozzle or perform post-print immersion/misting in crosslinker.

- For photocrosslinkable materials (e.g., GelMA), integrate a UV source at the print head for in-situ gelation.

- Post-Processing: Transfer the printed construct to a culture dish with complete medium. Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

Protocol 3: Assessment of Cell Viability and Function Post-Printing

Aim: To quantify the impact of the extrusion process on cell health and phenotype.

Materials:

- Printed construct (from Protocol 2)

- Live/Dead assay kit (Calcein AM / Ethidium homodimer-1)

- Cell viability/cytotoxicity assay (e.g., AlamarBlue, MTT)

- Confocal/multiphoton microscope

- Histology/Immunostaining reagents

Method:

- Viability (Live/Dead Assay):

- At 1, 24, and 72 hours post-printing, incubate constructs in Live/Dead stain solution per manufacturer protocol.

- Image using confocal microscopy at multiple depths (Z-stack).

- Quantify: % Viability = (Live cells / (Live+Dead cells)) * 100.

- Metabolic Activity (AlamarBlue Assay):

- Incubate constructs in medium with 10% AlamarBlue reagent for 2-4 hours at 37°C.

- Measure fluorescence (Ex/Em: 560/590 nm). Plot relative fluorescence units (RFU) over time as a proxy for proliferation.

- Phenotype Assessment (Histology):

- At 7-14 days, fix constructs, dehydrate, embed (e.g., in OCT), and section.

- Perform H&E staining for general morphology and specific immunostaining (e.g., Collagen I for osteoblasts, Aggrecan for chondrocytes) to confirm phenotype retention.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Extrusion-Based Bioprinting of High-Cell-Density Constructs

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Alginate (High G-Content) | Rapid ionic crosslinking with Ca²⁺ provides immediate shape fidelity for soft, cell-dense structures. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable, bioactive hydrogel mimicking the RGD motifs of native ECM; excellent for cell adhesion. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (MeHA) | Shear-thinning, photocrosslinkable; key component for cartilage and neural tissue bioinks. |

| Fibrinogen/Thrombin | Forms a natural fibrin clot; promotes excellent cell migration and angiogenesis in dense constructs. |

| Nanocellulose / Silk Fibroin | Reinforcing agents added to soft hydrogels to enhance mechanical strength for printing. |

| Sacrificial Pluronic F127 | Used to print perfusable channels within dense constructs; liquefies at low temperature and is washed out. |

| RGD Peptide | Synthetically added to less-adhesive hydrogels (e.g., pure alginate) to promote cell attachment. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) Solution | Crosslinking agent for alginate bioinks; often applied as a mist or in a support bath. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-Trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Efficient, cytocompatible photoinitiator for UV/Viscous light crosslinking of polymers like GelMA. |

| Carbopol Support Bath | A yield-stress fluid that enables freeform embedding printing of low-viscosity, high-cell-density bioinks. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: EBB Workflow for High-Cell-Density Constructs

Diagram 2: Shear Stress Impact on Cell Viability Pathways

Within the broader thesis on 3D bioprinting techniques for porous biomimetic scaffolds, inkjet bioprinting emerges as a critical non-contact, droplet-based modality for fabricating hierarchical vascular networks. This technology enables the precise spatial deposition of living cells, bioinks, and signaling molecules to create perfusable, lumen-like structures essential for sustaining engineered tissues. Recent advances focus on improving resolution, cell viability, and the complexity of printed architectures to mimic native vasculature's mechanical and biochemical properties.

Key applications include:

- Pre-vascularized Tissue Constructs: Creating capillary-like networks within larger tissue scaffolds (e.g., for bone, cardiac, or skin tissue) to enhance post-implantation integration and survival.

- Organ-on-a-Chip and Disease Models: Printing endothelial-lined microfluidic channels to study vascular biology, drug transport, and pathological processes like cancer metastasis or atherosclerosis in a controlled setting.

- Angiogenic Factor Screening: Precisely patterning gradients of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or other morphogens to study and guide neovascularization.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Contemporary Inkjet Bioprinters for Vascular Applications

| Parameter | Typical Range | Optimal Target for Vasculature | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet Volume | 1 – 100 picoliters (pL) | 1 – 10 pL | Determines printing resolution and single-cell deposition capability. |

| Printing Resolution (XY) | 10 – 50 µm | 10 – 20 µm | Defines the fineness of printed vessel branches and wall definition. |

| Cell Density in Bioink | 1x10^6 – 1x10^7 cells/mL | 1-5x10^6 cells/mL | Balances cell-cell interaction and printability/nozzle clogging. |

| Post-Printing Viability | 85% – 95% | >90% | Critical for endothelial cell function and network formation. |

| Maximum Printing Speed | 1 – 10 kHz (droplet frequency) | 1 – 5 kHz | Speed must be balanced against precision for complex networks. |

| Feature Size (Vessel Diameter) | 50 – 300 µm | 50 – 100 µm | Targets the scale of pre-capillary arterioles and venules. |

Table 2: Common Bioink Formulations for Vascular Inkjet Printing

| Bioink Base Component | Crosslinking Method | Key Advantage for Vasculature | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate (Low Viscosity) | Ionic (CaCl₂) | Rapid gelation, good structural definition. | Low bioactivity, requires modification with RGD peptides. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photo (UV/Light) | Tunable stiffness, naturally cell-adhesive. | May require viscosity modifiers for reliable jetting. |

| Fibrin | Enzymatic (Thrombin) | Excellent biological cues for endothelial maturation. | Low mechanical stability, fast degradation. |

| Hyaluronic Acid Derivatives | Photo or Ionic | Mimics native extracellular matrix, promotes morphogenesis. | Can be challenging to optimize for jetting parameters. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Printing a 2D Endothelial Network Pattern

Objective: To create a planar, patterned endothelial cell network for angiogenesis studies.

Materials:

- Thermo- or piezoelectric inkjet bioprinter.

- Sterile, low-viscosity GelMA bioink (5-7% w/v).

- Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs).

- Photoinitiator (LAP, 0.25% w/v).

- Sterile PBS and cell culture medium (EGM-2).

- Treated glass slide or Petri dish.

Methodology:

- Bioink Preparation: Mix HUVECs at 3x10^6 cells/mL into sterile, cold GelMA solution containing photoinitiator. Keep on ice to prevent premature gelation.

- Printer Setup: Load bioink into a sterile print cartridge. Calibrate droplet ejection using waveform optimization. Define a 2D branching pattern (e.g., a fractal or honeycomb design) in printing software.

- Printing: Print the pattern onto the substrate maintained at 15°C.

- Crosslinking: Immediately expose the printed structure to 405 nm light (5-10 mW/cm²) for 30-60 seconds to crosslink the GelMA.

- Culture: Gently flood the substrate with EGM-2 medium. Culture at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Monitor network formation and endothelial junction development over 3-7 days.

Protocol 2: Sequential Printing of a Perfusable Bifurcating Channel

Objective: To fabricate a simple 3D perfusable channel with an endothelial lining.

Materials:

- Multi-cartridge inkjet bioprinter.

- Bioink Cartridge 1: Sacrificial bioink (e.g., 10% w/v Pluronic F-127).

- Bioink Cartridge 2: Structural bioink (e.g., 4% Alginate).

- Bioink Cartridge 3: Cell-laden bioink (HUVECs in 3% GelMA).

- Crosslinking agent (100 mM CaCl₂ solution).

- Perfusion chamber setup.

Methodology:

- Print Sacrificial Core: Print a linear filament with a "Y" bifurcation using the Pluronic F-127 ink onto a cooled stage (4°C). This acts as a temporary mold.

- Encapsulate with Structural Layer: Print the alginate bioink around the sacrificial core to form an outer wall. Immediately crosslink by misting with CaCl₂ solution.

- Remove Sacrificial Core: Raise temperature to 20°C and wash with culture medium to liquefy and remove the Pluronic F-127, leaving a hollow channel.

- Seed Endothelial Lining: Print the HUVEC-laden GelMA bioink directly into the hollow channel. Photo-crosslink briefly.

- Maturation: Connect the channel ends to a perfusion system with a low flow rate (0.1 mL/min) of EGM-2 medium. Culture for 5-14 days to allow endothelial monolayer formation.

Visualization: Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Title: Inkjet Bioprinting Workflow

Title: Key VEGF Signaling in Printed Endothelia

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Inkjet Bioprinting of Vascular Networks

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Piezoelectric Printhead | Provides precise, gentle droplet ejection via mechanical vibration. Preferred for cell printing due to lower thermal stress. | MicroFab Technologies Jetlab series. |

| Low-Viscosity GelMA | A photo-crosslinkable, cell-adhesive hydrogel base. Allows high-resolution printing and supports endothelial cell spreading. | Merck (Sigma-Aldrich) or Engityre. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-Trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | A biocompatible photoinitiator for visible light crosslinking. Enables rapid gelation with low cytotoxicity. | Superior to Irgacure 2959 for cell-laden bioinks. |

| Pluronic F-127 | A thermoreversible sacrificial ink. Solidifies when cool, liquefies when warm, allowing creation of hollow channels. | Used as a fugitive ink for lumen fabrication. |

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF-165) | Critical morphogen to include in bioink or culture medium. Drives endothelial proliferation, migration, and network maturation. | Human recombinant protein, often used at 10-50 ng/mL. |

| Peristaltic Micro-Perfusion System | Provides controlled, low-shear flow through printed channels. Essential for endothelial shear stress signaling and lumen maturation. | Ibidi or Elveflow systems. |

Light-assisted bioprinting, encompassing Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP), is a vat-photopolymerization technique pivotal for fabricating biomimetic scaffolds with high architectural fidelity. Within the broader thesis on 3D bioprinting for porous biomimetic scaffolds, these techniques address the critical need for replicating the complex, micron-scale geometries of native extracellular matrix (ECM). Unlike extrusion-based methods, SLA/DLP offer superior resolution (≈10-50 µm), smooth surface finishes, and the ability to create intricate internal pore networks—essential for nutrient diffusion, cell migration, and vasculogenesis.

Current Applications:

- Bone & Osteochondral Tissue Engineering: Fabrication of scaffolds with graded porosity and mechanically tunable zones mimicking cortical and cancellous bone.

- Vascularized Constructs: Creation of branched, perfusable channel networks within hydrogels to support tissue viability beyond diffusion limits.

- High-Throughput Drug Screening: Generation of arrays of precise, tissue-mimetic microstructures for consistent in vitro testing.

- Patient-Specific Implants: Utilization of clinical imaging data (CT/MRI) to print anatomically accurate, bioactive scaffolds.

Key Advantages:

- High Resolution: Achieves feature sizes down to 10 µm, enabling capillary-level detail.

- Structural Complexity: Creates true 3D lattices (e.g., gyroid, diamond) with controlled porosity (>90%) and interconnectivity.

- Speed (DLP): Whole-layer projection significantly reduces print time compared to point-scanning SLA.

- Cell-Laden Printing: Compatible with bioinks containing live cells (cytocompatible photoinitiators and wavelengths) for direct bioprinting.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Light-Assisted Bioprinting Techniques

| Parameter | Stereolithography (SLA) | Digital Light Processing (DLP) | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical XY Resolution | 10 - 50 µm | 10 - 100 µm | Dependent on laser spot size or pixel size. |

| Typical Z Resolution (Layer Height) | 10 - 100 µm | 10 - 100 µm | Adjustable, impacts print time and surface finish. |

| Print Speed | 1 - 20 mm³/hour | 10 - 100 mm³/hour | Speed varies greatly with resolution and part volume. DLP is faster for full layers. |

| Bioink Viscosity Range | 1 - 300 mPa·s | 5 - 5000 mPa·s | DLP can often process higher viscosities due to vat dynamics. |

| Common Photoinitiator Concentration | 0.1 - 1.0 % (w/v) | 0.05 - 0.5 % (w/v) | Lower concentrations often sufficient for DLP due to high light intensity. |

| Cytocompatible Wavelength | 365 nm, 405 nm (UV-Vis) | 365 nm, 405 nm (UV-Vis) | Longer wavelengths (e.g., 405 nm) reduce cell phototoxicity. |

| Mechanical Strength (Typical Crosslinked Gelatin Methacryloyl) | Elastic Modulus: 5 - 100 kPa | Elastic Modulus: 5 - 200 kPa | Highly tunable via polymer concentration, crosslink density, and processing parameters. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DLP Bioprinting of a Cell-Laden, Porous Gyroid Scaffold with Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA)

Aim: To fabricate a high-resolution, biomimetic scaffold with interconnected porosity for 3D cell culture.

I. Materials & Pre-Print Preparation

- Bioink Formulation:

- GelMA (10% w/v): Dissolve lyophilized GelMA in warm (37°C) PBS or culture medium. Sterile filter (0.22 µm).

- Photoinitiator: Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP), 0.25% (w/v). Add to cooled GelMA solution (<30°C) and mix gently in low light.

- Cells: Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs), passage 4-6. Trypsinize, count, and resuspend in a small volume of medium.

- Final Bioink: Gently mix cell suspension into GelMA-LAP solution to a final density of 1-5 x 10^6 cells/mL. Keep on ice, protected from light.

- CAD Model Preparation:

- Design a 10 x 10 x 2 mm gyroid lattice unit cell with a pore size of 300 µm using CAD software (e.g., SolidWorks, nTopology).

- Slice the model into 2D layers (e.g., 50 µm layer thickness) using the printer's proprietary software or a compatible slicer (e.g., CHITUBOX). Export as a sequence of bitmap images.

II. Bioprinting Procedure

- Printer Setup: Sterilize the DLP printer vat and build platform with 70% ethanol and UV light. Preheat the build plate to 15-18°C.

- Bioink Loading: Pour the cell-laden GelMA bioink into the vat.

- Printing Parameters: Set the following in the printer software:

- Layer Thickness: 50 µm

- Exposure Time: 2 - 8 seconds/layer (optimize for crosslinking depth)

- Light Intensity: 5 - 15 mW/cm² @ 405 nm

- Rest Time After Exposure: 1 second

- Initiate Print: Start the print job. The build platform will descend, and each layer will be projected and crosslinked sequentially.

- Post-Print Retrieval: After completion, raise the platform and carefully remove the printed construct using a sterile spatula.

III. Post-Print Processing & Culture

- Rinsing: Rinse the scaffold gently in warm, sterile PBS to remove uncrosslinked polymer.

- Further Crosslinking (Optional): Immerse the scaffold in a PBS solution containing 0.1% LAP and expose to a low-intensity 405 nm light for 30-60 seconds to ensure complete gelation.

- Cell Culture: Transfer the scaffold to a 24-well plate. Add complete culture medium and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Change medium every 2-3 days.

Protocol 2: SLA Bioprinting of a Multi-Material, Graded Scaffold

Aim: To create a scaffold with spatially controlled mechanical properties using a multi-resin SLA system.

I. Materials & Preparation

- Resin A (Soft Zone): 8% (w/v) GelMA, 0.15% LAP.

- Resin B (Stiff Zone): 15% (w/v) GelMA, 0.3% LAP, supplemented with 1% (w/v) hydroxyapatite nanoparticles.

- CAD Model: Design a rectangular scaffold (15 x 15 x 5 mm) with a defined internal region for Resin B.

II. Bioprinting Procedure

- Printer Setup: Use an SLA printer equipped with a resin-switching mechanism. Load Resin A into the primary vat and Resin B into a secondary reservoir.

- Slicing & Material Assignment: In advanced slicing software, assign specific layers or regions to be printed with Resin B.

- Printing:

- The printer begins, constructing layers with Resin A using a focused UV laser (λ=365 nm, scan speed=1500 mm/s, power=200 mW).

- At the designated layer, the build platform rises, the vat drains, Resin B is pumped in, and printing resumes for the assigned region.

- The vat is flushed, Resin A is reintroduced, and printing completes.

- Post-Processing: Retrieve scaffold, rinse thoroughly in PBS, and sterilize under UV light.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Light-Assisted Bioprinting

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Methacrylated Polymers (GelMA, Hyaluronic Acid Methacrylate) | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel backbone providing biological cues and tunable physical properties. | Advanced BioMatrix (GelMA), Sigma-Aldrich. |

| Cytocompatible Photoinitiator (LAP, Irgacure 2959) | Initiates polymerization upon light exposure without generating excessive cytotoxic free radicals. | Toronto Research Chemicals (LAP), Sigma-Aldrich (Irgacure 2959). |

| UV-Absorbing Dye (Tartrazine, Food Dye Yellow #5) | Added in trace amounts (≈0.01% w/v) to control light penetration depth, improving Z-resolution. | Sigma-Aldrich. |

| Dynamic Binding Peptides (RGD, MMP-sensitive peptides) | Incorporated into the bioink to enhance specific cell adhesion and provide cell-remodelable crosslinks. | Peptide synthesis vendors (e.g., GenScript). |

| Nanoparticle Additives (Hydroxyapatite, Laponite) | Enhance mechanical properties (stiffness, toughness) and introduce bioactivity (osteoconduction). | Sigma-Aldrich, BYK Additives. |

| Support Bath (Carbopol, PF127) | A yield-stress fluid used in freeform SLA/DLP to print low-viscosity bioinks without a solid vat. | Lubrizol (Carbopol), Sigma-Aldrich (Pluronic F127). |

Diagrams

Light-Assisted Bioprinting Workflow

Cell-Scaffold Interaction Signaling

Laser-Assisted Bioprinting (LAB) is a nozzle-free, non-contact bioprinting technique enabling high-resolution, high-viability patterning of living cells and biomaterials. Within the broader thesis on 3D bioprinting techniques for constructing porous biomimetic scaffolds, LAB addresses a critical limitation: the precise spatial arrangement of multiple cell types within a 3D matrix to mimic native tissue microarchitecture. Unlike extrusion-based methods, LAB avoids shear stress, making it ideal for patterning sensitive primary cells and co-cultures into predefined, often porous, hydrogel scaffolds to create complex tissue models for regenerative medicine and drug development.

Core Principles and Quantitative Performance Data

LAB operates on the Laser-Induced Forward Transfer (LIFT) principle. A pulsed laser beam is focused on a donor substrate ("ribbon") coated with a thin layer of bioink. This generates a high-pressure bubble, propulating a microdroplet of bioink containing cells toward a collector substrate. Key performance metrics are summarized below.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Laser-Assisted Bioprinting

| Performance Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Impact on Scaffold Research |

|---|---|---|

| Print Resolution (Cell Level) | Single cell to ~50 µm droplets | Enables single-cell patterning within porous networks. |

| Cell Viability Post-Print | 85% - 95% (within 24h) | High viability maintains cell function for long-term culture in scaffolds. |

| Printing Speed | 1 - 10,000 droplets per second | Influences scalability for fabricating large, cell-laden scaffolds. |

| Bioink Viscosity Range | 1 - 300 mPa·s | Compatible with low-viscosity, cell-friendly hydrogels (e.g., collagen, alginate). |

| Cell Density in Bioink | 1x10^6 - 1x10^8 cells/mL | Allows for physiologically relevant cell densities in printed constructs. |

| Max Cell Types per Print Session | Typically 1-4 (multi-ribbon systems) | Facilitates creation of complex, multi-cellular tissue interfaces in porous scaffolds. |

Table 2: LAB vs. Other Bioprinting Techniques for Porous Scaffold Fabrication

| Technique | Cell Viability | Resolution | Suitability for Porous Soft Hydrogels | Key Limitation for Scaffold Patterning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser-Assisted (LAB) | Very High (90-95%) | High (μm) | Excellent | Throughput, limited bioink viscosity. |

| Extrusion-Based | Moderate-High (70-90%) | Low-Med (100-500 μm) | Good (if crosslinked) | Shear stress can damage cells. |

| Inkjet-Based | High (85-90%) | Medium (50-100 μm) | Good (low viscosity) | Clogging, limited cell density. |

| Stereolithography (SLA) | Medium (80-90%) | Very High (10-100 μm) | Excellent (photopolymers) | UV/photoinitiator cytotoxicity. |

Detailed Application Notes

Application in Multi-Cellular Porous Scaffold Patterning

A primary application is sequentially printing endothelial cells and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) into a porous gelatin-methacryloyl (GelMA) scaffold to create a pre-vascularized bone model. LAB first patterns HUVECs in a branching network geometry, followed by MSCs in the surrounding matrix. This exploits LAB's high spatial resolution and multi-material capability to engineer complex tissue interfaces within a 3D porous environment.

Application in High-Throughput Drug Screening Micromodels

LAB can print patient-derived tumor spheroids/organoids into arrays within a porous collagen scaffold housed in a multi-well plate. This creates physiologically relevant 3D micro-tumors with stromal interactions for high-content drug testing. High post-print viability ensures reliable response metrics.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: LAB Patterning of a Co-Culture within a Porous GelMA Scaffold

Objective: To create a patterned co-culture of HUVECs and MSCs in a 5% (w/v) GelMA scaffold with >85% viability.

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" (Section 6).

Pre-Experiment:

- Scaffold Preparation: Synthesize and characterize porous GelMA scaffolds (e.g., via freeze-drying or porogen leaching) to achieve ~200 µm mean pore size. Sterilize with 70% ethanol and UV irradiation.

- Bioink Preparation:

- HUVEC Bioink: Suspend HUVECs (P3-P5) at 5x10^6 cells/mL in sterile PBS with 1% (v/v) alginate (for droplet stabilization).

- MSC Bioink: Suspend MSCs (P3-P5) at 10x10^6 cells/mL in sterile PBS with 1% (v/v) alginate.

- Ribbon Coating: Coat a gold/nanoporous titanium donor ribbon (absorbing layer) with ~60 µm thickness of the respective bioink.

LAB Printing Procedure:

- System Setup: Place sterile porous GelMA scaffold on the collector stage (coated with GelMA precursor). Maintain stage at 15°C.

- Laser Calibration: Use a low-energy (e.g., 30 µJ) pulse from a Nd:YAG laser (λ=1064 nm, pulse duration ~10 ns) to test droplet formation and adjust focus.

- First Cell Pattern Printing: Load HUVEC-coated ribbon. Program the laser path to print a branching network pattern onto the scaffold. Typical parameters: 35 µJ pulse energy, 5 kHz frequency.

- Scaffold Partial Crosslinking: Expose the scaffold to blue light (405 nm, 5 mW/cm²) for 60 sec to partially crosslink the printed HUVECs in place.

- Second Cell Pattern Printing: Replace ribbon with MSC-coated ribbon. Program a fill pattern around the HUVEC network. Print using similar parameters (35 µJ).

- Final Crosslinking: Crosslink the entire construct for 180 sec to achieve full scaffold gelation.

Post-Printing Analysis:

- Viability Assay: After 24h culture (EGM-2/Mesencult media, 1:1 mix), incubate with Calcein-AM (2 µM) and Ethidium homodimer-1 (4 µM) for 45 min. Image via confocal microscopy.

- Viability Quantification: Viability (%) = (Calcein+ cells / (Calcein+ + EthD-1+ cells)) * 100. Calculate from 5 random fields (n≥3 constructs).

Protocol 2: Viability Assessment Post-LAB (Live/Dead Assay)

Objective: To quantify cell viability within 24 hours of LAB printing.

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a 4 µM EthD-1 and 2 µM Calcein-AM solution in cell culture medium (without serum).

- Staining: Aspirate medium from printed construct. Add enough staining solution to cover. Incubate for 30-45 minutes at 37°C, protected from light.

- Imaging: Rinse gently with PBS. Image immediately using a confocal microscope (e.g., 488 nm excitation for Calcein, 561 nm for EthD-1). Take z-stacks for 3D constructs.

- Analysis: Use ImageJ/Fiji with cell counter plugin. Count green (live) and red (dead) cells in at least three independent fields of view per sample.

Visualizations

Title: LAB Process for Multi-Cell Scaffold Patterning

Title: Cellular Stress & Viability Pathways in LAB

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Laser-Assisted Bioprinting Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations for High Viability |

|---|---|---|

| Gold/Titanium Donor Ribbon | Laser-absorbing layer for bubble generation. | Nanoporosity enhances bioink film uniformity and jet stability. |

| Low-Viscosity Hydrogel Precursor (e.g., GelMA, Alginate) | Forms the printable bioink matrix; later crosslinked. | Must have low viscosity (<30 mPa·s) for clean droplet formation. |

| Cell-Friendly Photoinitiator (e.g., LAP) | Initiates crosslinking of photopolymer bioinks under cytocompatible light. | LAP (Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate) allows visible light crosslinking, less toxic than Irgacure 2959. |

| Programmable XYZ Stage | Precisely positions collector substrate/scaffold. | Micrometer precision needed for aligning multiple cell patterns within scaffold pores. |

| Pulsed Laser Source (e.g., Nd:YAG) | Provides the energy pulse for droplet ejection. | Nanosecond pulses (e.g., 10 ns) minimize thermal diffusion and cell damage. |

| Sterile Environment Enclosure | Maintains aseptic conditions during printing. | Critical for long-term culture of printed constructs; often integrated HEPA filter. |

| Calcein-AM / EthD-1 Live/Dead Kit | Standard assay for quantifying post-print viability. | Calcein-AM stains live cells (green), EthD-1 stains dead cells (red). Use within 24h of printing. |

| Matrigel or Fibrinogen | Additive for bioink to enhance cell adhesion & signaling. | Improves post-print cell survival and function within synthetic scaffolds like GelMA. |

Emerging Hybrid and Multi-Modal Bioprinting Strategies

Application Notes

Hybrid and multi-modal bioprinting integrates complementary fabrication techniques to overcome the limitations of single-modality printing, enabling the creation of complex, hierarchical, and biomimetic porous scaffolds. This approach is critical for replicating the nuanced microenvironments of native tissues, which often require gradients of materials, cells, and porosities. The strategic combination of methods such as extrusion, inkjet, stereolithography (SLA), and melt electrowriting (MEW) allows for the simultaneous deposition of high-strength structural filaments and high-resolution, cell-laden bioinks. These scaffolds show significant promise in advancing regenerative medicine, high-fidelity disease modeling, and more physiologically relevant drug screening platforms.

Key Advantages:

- Structural Integrity & Resolution: MEW or SLA can create micrometer-scale, mechanically robust frameworks, which are then infilled with cell-laden hydrogels via extrusion or inkjet printing.

- Spatial Heterogeneity: Multi-modal printing facilitates the creation of region-specific compositions, enabling co-culture systems and graded interfaces mimicking osteochondral or vascular tissues.

- Improved Viability & Function: By separating the printing of supportive structures from cell deposition, harsh crosslinking conditions can be isolated, leading to higher post-print cell viability and functionality.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hybrid Extrusion-SLA Bioprinting of Osteochondral Scaffold

Aim: To fabricate a biphasic scaffold with a dense, osteoconductive bone region and a porous, chondrocyte-laden cartilage region.

Materials:

- SLA Printer: Equipped with 405 nm laser.

- Extrusion Bioprinter: Pneumatic or mechanical, with temperature control.

- Bioink for Bone Region: Photocurable resin containing 20% (w/v) hydroxyapatite (HA) nanoparticles and poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA).

- Bioink for Cartilage Region: Alginate (3% w/v) - gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) (5% w/v) blend laden with human chondrocytes (10 million cells/mL).

- Crosslinkers: 0.1M Calcium chloride (CaCl₂) solution, Photoinitiator (LAP, 0.25% w/v) in PBS.

Procedure:

- SLA Printing of Bone Layer:

- Load the HA-PEGDA resin into the SLA printer vat.

- Use the designed CAD model (dense, porous network with ~200 µm pores) to print the bottom bone layer (e.g., 5 mm height). Layer-by-layer polymerization is achieved with 405 nm light (100 mW/cm², 5 s exposure per layer).

- Post-print, rinse the structure in ethanol to remove uncured resin and cure under broad-spectrum UV for 5 minutes.

Extrusion Bioprinting of Cartilage Layer:

- Mount the SLA-printed bone scaffold onto the extrusion printer's build plate.

- Load the alginate-GelMA-chondrocyte bioink into a sterile cartridge maintained at 18°C.

- Print the porous cartilage lattice (e.g., 300 µm nozzle, 150 kPa pressure, 8 mm/s speed) directly onto the bone layer, using a cross-hatch pattern with 500 µm spacing.

- Simultaneously co-axially spray 0.1M CaCl₂ for ionic crosslinking of alginate.

Secondary Crosslinking:

- Immerse the entire hybrid construct in a LAP solution and expose to 405 nm light (20 mW/cm², 60 s) for covalent crosslinking of GelMA.

Culture & Analysis:

- Transfer to chondrogenic medium. Assess cell viability (Live/Dead assay) at days 1, 7, and 14. Perform mechanical compression testing and histological analysis (Safranin O for glycosaminoglycans) at week 4.

Protocol 2: Multi-Modal Inkjet-MEW Bioprinting for Vascularized Constructs

Aim: To create a prevascularized tissue construct with a perfusable MEW core scaffold surrounded by a parenchymal cell niche.

Materials:

- MEW Printer: High-voltage setup, heated syringe.

- Inkjet Printer: Piezoelectric, with heated printheads.

- MEW Polymer: Medical-grade poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL).

- Bioinks: Ink A: Fibrinogen (20 mg/mL) with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, 5 million cells/mL). Ink B: Collagen I (5 mg/mL) with human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs, 10 million cells/mL).

- Crosslinker: Thrombin solution (2 U/mL).

Procedure:

- MEW of Core Microfiber Scaffold:

- Load PCL into a syringe heated to 85°C.

- Print a tubular, porous mesh (fiber diameter: 15 µm, pore size: 150 µm x 150 µm) using MEW parameters (voltage: 4 kV, pressure: 0.8 bar, collector speed: 300 mm/s).

Inkjet Deposition of Vascular Lining:

- Mount the MEW scaffold on the inkjet stage.

- Load Ink A (HUVEC-laden fibrinogen) into the printhead (maintained at 22°C).

- Precisely jet droplets (~70 pL) onto the PCL microfiber surfaces to coat them with a continuous endothelial cell layer. Use a printing pattern that follows the fiber paths.

Fibrin Gelation:

- Immediately after inkjet printing, mist the construct with thrombin solution (2 U/mL) to initiate fibrin polymerization, immobilizing the HUVECs.

Inkjet Deposition of Parenchymal Niche:

- Load Ink B (hMSC-laden collagen) into a separate printhead.

- Print droplets to fill the porous spaces between the endothelial-coated MEW fibers.

- Transfer the construct to a 37°C incubator for 30 minutes for collagen gelation.

Culture & Analysis:

- Culture in endothelial growth medium (EGM-2). Monitor HUVEC confluence and lumen formation via confocal microscopy (CD31 staining) over 7 days. Assess hMSC viability and spatial organization.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Modal Bioprinting Strategies

| Strategy Combination | Key Resolutions Achieved | Reported Cell Viability (>Day 7) | Typical Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion + SLA | Extrusion: 200-500 µm; SLA: 25-100 µm | 85-92% | Osteochondral Tissue, Hard-Soft Interfaces | High structural precision combined with cell-laden hydrogel deposition. |

| Inkjet + MEW | Inkjet: 50-100 µm (droplet); MEW: 5-20 µm (fiber) | 90-95% | Vascularized Constructs, Filter Systems | Micrometer-scale fibrous architecture with precise cell placement. |

| Extrusion + Inkjet | Extrusion: 150-400 µm; Inkjet: 50-150 µm | 80-90% | Gradient Constructs, Multi-Cell Type Patterns | High-throughput cell deposition with structural support. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Hybrid Bioprinting

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel providing cell-adhesive RGD motifs; a versatile bioink base for extrusion, inkjet, or SLA. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | Photocurable, bioinert polymer used in SLA; tunable mechanical properties, often combined with bioactive additives. |

| Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | Thermoplastic polyester for MEW; provides long-term, tunable mechanical stability to hybrid constructs. |

| Laponite XLG | Nanosilicate clay used as a rheological modifier; enhances print fidelity of extrusion bioinks and supports cell function. |

| Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Efficient, cytocompatible photoinitiator for UV (365-405 nm) crosslinking of methacrylated hydrogels. |

| Alginate (High G-Content) | Rapidly ionically crosslinked polysaccharide; used for cell immobilization and as a sacrificial material. |

| Fibrinogen/Thrombin | Forms natural fibrin hydrogel upon mixing; excellent for angiogenesis and cell migration studies. |

Visualizations

Title: Hybrid Extrusion-SLA Bioprinting Workflow

Title: Scaffold-Cell Signaling in Multi-Modal Bioprinting

This Application Note details practical protocols for the 3D bioprinting of porous, biomimetic scaffolds for three critical tissues. It directly supports the broader thesis that "multi-material, extrusion-based bioprinting, integrated with bioactive factor delivery, is paramount for creating hierarchically porous scaffolds that recapitulate native tissue microarchitecture and function." The focus is on translating bioprinting techniques into actionable experimental setups for bone, cartilage, and skin regeneration.

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Target Tissues, Biomaterials, and Key Outcomes

| Tissue | Primary Biomaterials | Pore Size (µm) Target | Key Bioactive Factors | Typical Cell Source | Maturation Time (Days) | Key Mechanical/Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | Alginate-Gelatin-Methacrylate (GelMA) w/ β-TCP, Nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) | 300-500 | BMP-2, VEGF | Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) | 21-28 | Compressive Modulus: 0.5 - 2.5 MPa; Significant mineral deposition (Alizarin Red S+) |

| Cartilage | Hyaluronic Acid Methacrylate (HAMA), Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | 100-200 | TGF-β3, BMP-6 | Chondrocytes, hMSCs | 14-21 | Compressive Modulus: 0.2 - 0.8 MPa; GAG/DNA content >80% of native tissue |