Biomimethics in Biomedicine: Integrating Ethical Frameworks for Sustainable Drug Development

This article examines the critical intersection of bioethics and biomimicry for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Biomimethics in Biomedicine: Integrating Ethical Frameworks for Sustainable Drug Development

Abstract

This article examines the critical intersection of bioethics and biomimicry for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational ethical principles of learning from nature, outlines methodological frameworks for application, addresses challenges in implementing biomimetic strategies, and validates the approach through comparative analysis with conventional methods. The synthesis provides a roadmap for integrating nature-inspired, ethically-grounded innovation into biomedical research and clinical practice to advance sustainable and effective therapeutic solutions.

The Ethical Bedrock of Biomimicry: Principles for Responsible Bio-Inspiration

Biomimicry, the practice of learning from and emulating nature's strategies to solve human challenges, represents a frontier in scientific innovation with applications ranging from materials science to drug development [1]. The core premise is that nature, through 3.8 billion years of evolution, has developed highly efficient, sustainable solutions to complex problems [2] [3]. While the technical aspects of biomimicry—the imitation of biological structures and processes—have advanced significantly, the ethical dimensions require parallel development. This framework establishes biomimicry ethics as the responsible transition from mere technical imitation to value-driven emulation, with particular significance for drug development research where efficacy, safety, and sustainability intersect.

The ethical consideration in biomimicry extends beyond conventional research ethics to encompass environmental responsibility, symbiotic cooperation, and ecological alignment [2] [3]. In pharmaceutical development, this translates to methodologies that not only mimic biological structures but do so through processes that minimize environmental impact and respect ecological systems. This paper establishes both the philosophical foundation and practical methodology for implementing biomimetic ethics in research settings, with specific application to drug development challenges.

Theoretical Foundation: From Imitation to Emulation

Defining the Biomimetic Ethical Spectrum

Biomimetic research spans a continuum from superficial technical imitation to profound ecological emulation. The distinction between these approaches carries significant ethical implications for research design and implementation.

Technical Imitation involves adopting nature's designs without considering the underlying ecological principles or sustainability. This approach might yield innovative solutions but risks replicating nature's outputs without its efficiency or environmental harmony. Examples include early biomimetic materials that mimicked biological structures but required energy-intensive manufacturing processes.

Responsible Emulation, in contrast, embraces nature's overarching principles: optimizing for multiple functions, using life-friendly chemistry, and maintaining systems within ecological boundaries [1] [4]. This approach aligns with the concept of "biomimicry thinking" – a philosophical orientation that considers nature not merely as a catalog of design solutions but as a mentor and standard for what constitutes sustainable innovation [1].

Ethical Principles Derived from Natural Systems

Natural systems offer robust ethical frameworks when properly understood. The collaboration between University of Akron philosophers and biologists has identified key principles for ethical biomimicry [2] [3]:

- Symbiotic Cooperation: Emulating mutualistic relationships where entities coexist beneficially rather than competitively

- Resource Efficiency: Prioritizing energy and material conservation as observed in natural systems

- Ecological Embeddedness: Designing technologies and processes that align with planetary health

- Adaptive Resilience: Creating systems capable of responding to change while maintaining core functions

These principles provide a foundation for evaluating biomimetic research beyond technical efficacy to include ethical and ecological dimensions.

Biomimetic Ethics in Drug Development

Current Challenges in Pharmaceutical Development

The drug development pipeline faces significant ethical and practical challenges that biomimetic approaches may help address. Current statistics reveal the scope of these challenges:

Table 1: Drug Development Challenges and Biomimetic Opportunities

| Development Challenge | Traditional Approach Limitations | Biomimetic Ethical Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High failure rate in clinical trials (90%) [5] | Limited predictive capability of 2D culture and animal models | Development of more physiologically relevant 3D models inspired by human tissue architecture |

| Cardiovascular drug progression rate of only 7% [5] | Species differences in preclinical models | Human iPSC-derived organoids that better mimic human pathology |

| High development costs averaging $2.6 billion per approved drug [5] | Resource-intensive screening processes | Biomimetic efficiency in research design and execution |

| Cardiovascular toxicity concerns causing drug attrition [5] | Inadequate toxicity screening models | Organ-on-a-chip technology mimicking human physiological responses |

Ethical Frameworks for Biomimetic Drug Discovery

Biomimetic ethics in pharmaceutical research extends the principles of replacement, reduction, and refinement (the 3Rs) in animal testing [5]. The FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which overturned the mandate for animal testing in every new drug development protocol, has created regulatory space for biomimetic approaches [5]. This legislation advocates for integrating alternative methods including human iPSC-derived organoids and organ-on-a-chip technologies in conjunction with artificial intelligence methodologies [5].

The ethical framework for biomimetic drug development prioritizes:

- Human-Relevant Predictive Models: Shifting from animal models to human biomimetic systems that more accurately predict efficacy and toxicity

- Resource Efficiency: Implementing nature-inspired efficient research designs that reduce material and energy waste

- Sustainable Sourcing: Considering the environmental impact of biomimetic materials and processes

Methodological Implementation: Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing Biomimetic 3D Cardiac Tissues for Drug Screening

Objective: Create physiologically relevant human cardiac tissue models for more predictive and ethical cardiovascular drug testing.

Background: Traditional 2D culture systems lack the structural and mechanical cues necessary for native cardiomyocyte function. Numerous studies have shown myocyte cell behavior to be much more physiologically relevant in 3D culture compared to 2D culture [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomimetic 3D Cardiac Tissue

| Research Reagent | Function | Biomimetic Ethical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes | Provide patient-specific cardiac cells for disease modeling | Replacement of animal models, human-relevant data |

| Tunable synthetic hydrogel matrix | Mimics native cardiac extracellular matrix structure and stiffness | Avoids biologically-derived matrices (e.g., Matrigel) with undefined composition |

| Microfluidic perfusion system | Recreates nutrient and oxygen gradient similar to coronary circulation | Enables long-term culture without excessive media consumption |

| Electrical stimulation apparatus | Mimics native cardiac electrophysiological conditioning | Promotes mature cardiac phenotype without genetic manipulation |

| Mechanical stretching device | Recreates cyclic strain experienced by native myocardium | Enhances physiological relevance without animal-derived stimulants |

Methodology:

- Differentiation: Differentiate human iPSCs to cardiomyocytes using established small molecule protocols

- 3D Construction: Mix cardiomyocytes with tunable polyethylene glycol-based hydrogels at a density of 50-100 million cells/mL

- Mechanical Conditioning: Subject constructs to uniaxial stretching (10-15% strain) at 1Hz frequency for 7-14 days

- Electrical Conditioning: Apply field stimulation beginning at 0.5Hz, gradually increasing to 2Hz over 7 days

- Functional Assessment: Measure contractile force, conduction velocity, and calcium handling

- Drug Testing: Expose tissues to candidate compounds and measure functional changes

Ethical Validation: This protocol reduces animal use by providing more human-relevant preliminary data, potentially reducing late-stage failures due to species differences. The use of defined, synthetic matrices avoids the ethical concerns associated with animal-derived materials.

Protocol 2: Biomimetic Atherosclerosis Model for Anti-Inflammatory Drug Screening

Objective: Develop a biomimetic model of atherosclerotic plaque formation that captures the complexity of vascular inflammation while enabling high-throughput compound screening.

Background: Atherosclerosis involves complex interactions between vascular cells, inflammatory cells, and lipoproteins in a three-dimensional arterial environment. Traditional monolayer cultures cannot replicate these dynamics.

Methodology:

- Vessel-on-a-chip fabrication: Create microfluidic devices with parallel endothelialized channels (diameter: 100-200μm) embedded in a stromal compartment

- Cell seeding: Seed primary human endothelial cells in lumen and human vascular smooth muscle cells in surrounding matrix

- Hemodynamic conditioning: Apply pulsatile flow with arterial shear stress (10-20 dyn/cm²) and cyclic strain (5-10%)

- Disease induction: Introduce oxidized LDL (50-100μg/mL) and inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) to the circulation

- Monocyte recruitment: Introduce fluorescently labeled monocytes to the circulation and monitor adhesion and transmigration

- Compound testing: Introduce anti-inflammatory candidates and measure monocyte adhesion, cytokine production, and plaque characteristics

Ethical Validation: This human-based system provides pathophysiological insight without animal use and enables study of human-specific inflammatory pathways.

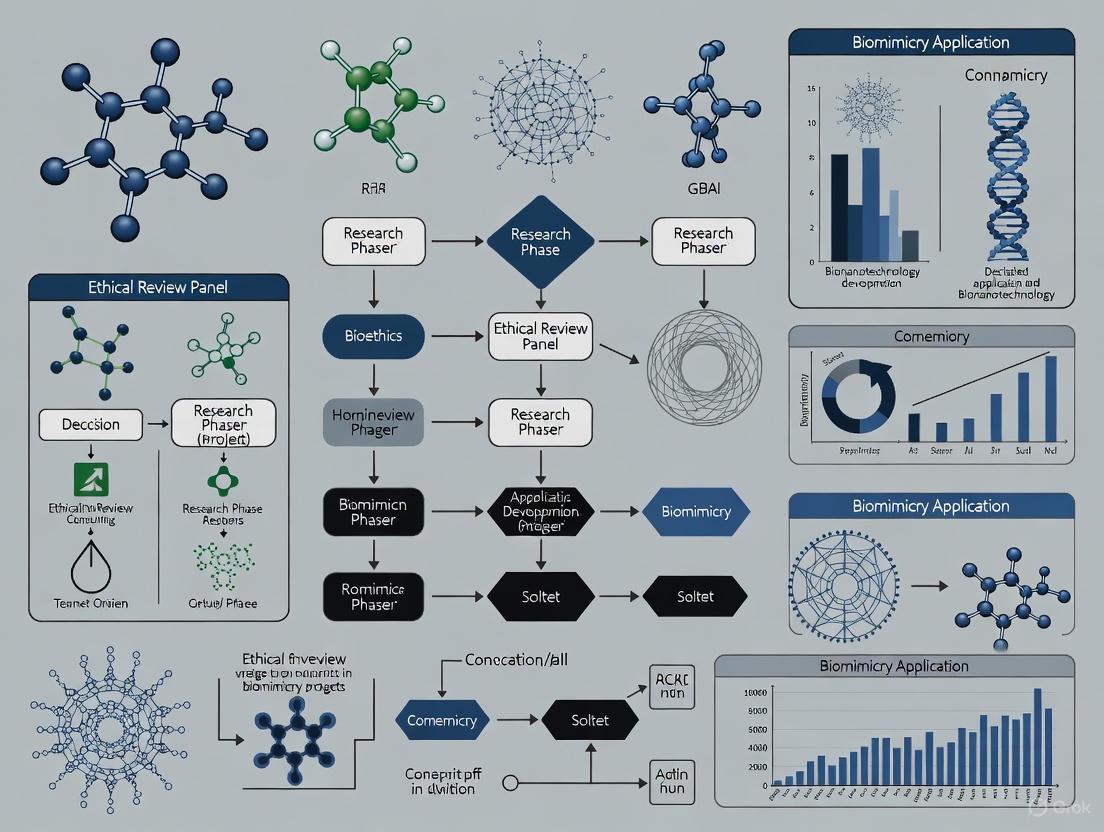

Visualization of Biomimetic Ethical Frameworks

Ethical Decision Framework for Biomimetic Research

Diagram 1: Biomimetic Ethics Decision Pathway

Biomimetic 3D Tissue Development Workflow

Diagram 2: Biomimetic Tissue Development Workflow

Quantitative Analysis of Biomimetic Approaches

Performance Metrics for Biomimetic Drug Screening Platforms

The implementation of biomimetic ethics in research requires quantitative validation to demonstrate both ethical and practical advantages.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Drug Screening Platforms

| Performance Metric | Traditional 2D Culture | Animal Models | Biomimetic 3D Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy for Human Toxicity | 30-40% [5] | 70-75% [5] | 85-90% (projected) |

| Species-specific Relevance | Human cells but non-physiological context | Limited by species differences | Human cells in physiological context |

| Throughput (samples/week) | High (1000+) | Low (10-100) | Medium-High (100-500) |

| Development Timeline | 1-3 months | 6-24 months | 3-9 months |

| Resource Consumption | Low per sample but high overall due to volume | Very high | Medium |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Well-established for early screening | Required for current approvals | Growing acceptance with FDA Modernization Act 2.0 [5] |

The transition from technical imitation to responsible emulation in biomimicry represents both an ethical imperative and practical opportunity for drug development research. By embracing nature's principles of efficiency, adaptation, and symbiosis, researchers can develop more predictive, human-relevant models while reducing environmental impact and animal use. The methodological frameworks presented herein provide actionable pathways for implementing biomimetic ethics across the drug development pipeline.

Future directions should include standardized ethical assessment metrics for biomimetic research, expanded regulatory frameworks for biomimetic models, and increased interdisciplinary collaboration between biologists, engineers, and ethicists. As noted by researchers at the University of Akron, alignment with ecological systems represents the next frontier in responsible innovation [2] [3]. Through committed application of these principles, biomimetic research can fulfill its potential to transform drug development while honoring its ethical obligations to both human and planetary health.

Biomimicry, the practice of emulating nature's models, systems, and elements to solve human challenges, is rapidly transforming research and development across industries from medicine to materials science [6]. While its technical potential is vast, its responsible implementation demands a rigorous ethical foundation. This whitepaper addresses the critical need for integrating core ethical frameworks—environmental ethics, bioethics, and the precautionary principle—into biomimicry research and development. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these frameworks provide essential guidance to ensure that innovations inspired by nature are developed and applied in a responsible, sustainable, and morally defensible manner [7].

The ethical practice of biomimicry requires a shift from a mentality of resource extraction to one of partnership with the natural world [8]. This involves acknowledging the intrinsic value of nature, independent of its direct utility for human innovation [8]. A purely utilitarian framework, which views organisms and ecosystems exclusively as repositories of valuable design blueprints, is insufficient and risks the commodification of biological life [8]. Ethical biomimicry, therefore, is predicated on a foundational ethical orientation that embeds a sense of stewardship and responsibility into the core of the research and design brief [8].

Core Ethical Frameworks and Their Application in Biomimicry

Environmental Ethics: From Anthropocentrism to Ecocentrism

Environmental ethics in biomimicry challenges the anthropocentric worldview that has traditionally framed nature as a resource for human exploitation [8]. This philosophical stance argues that human interests are of paramount importance, a perspective that can persist even in biomimicry if it merely views nature as a source of clever design solutions for human problems [9].

- Ecocentric and Biocentric Perspectives: A sophisticated ethical analysis requires a deconstruction of anthropocentrism in favor of ecocentric or biocentric perspectives, which attribute intrinsic value to all living organisms and ecosystems, independent of their utility to humans [8]. Adopting this view has profound implications, shifting the goal of biomimicry from creating more sustainable human artifacts to fostering a deeper integration of human systems within the biosphere [8].

- Respect for Life Principles: Operationalizing this shift, the "Respect for Life Principles," developed by the Biomimicry Institute, provide a foundational framework for ethical practice. These principles include recognizing the interconnectedness of all life, supporting biodiversity, using life-friendly materials and processes, and engaging in mutual benefit with nature [7].

- Strong vs. Weak Biomimicry: Research from Wageningen University further distinguishes between "strong" and "weak" biomimicry [9]. Strong biomimicry assumes the perfection of nature and views mimicry as a direct reproduction of nature. Weak biomimicry, considered more robust conceptually, acknowledges potential deficiencies in nature and the role of mimicry in supplementing it productively. This distinction helps avoid the naturalistic fallacy—the assumption that something is inherently good because it is natural [9].

Bioethics: Governing the Use of Biological Knowledge

Bioethics provides the moral principles for regulating research and applications involving biological systems. In biomimicry, bioethics plays a crucial role in determining the limits for the proper and conscious use of natural resources [6]. It encourages principles that connect human behavior with biological and medical management, designing complex systems that are both effective and ethically sound [6].

Key bioethical challenges in biomimicry include:

- Intellectual Property and Biopiracy: The legal frameworks for patents struggle to accommodate innovations derived from biological systems, raising profound questions about the ownership of designs refined over millions of years of evolution [8]. This challenge is compounded by the potential appropriation of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) held by indigenous communities. Ethical biomimicry requires robust frameworks for Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS), such as those outlined in the Nagoya Protocol, to ensure these communities provide consent, receive acknowledgment, and obtain equitable compensation for their knowledge [8].

- Ethical Sourcing and Benefit-Sharing: Businesses and research institutions engaged in biomimicry must ensure that biological models are sourced ethically and sustainably [7]. This involves obtaining proper permits and engaging in fair and transparent benefit-sharing agreements with countries of origin and indigenous communities, preventing biopiracy and promoting mutually beneficial relationships [8] [7].

The Precautionary Principle: Navigating Uncertainty and Risk

The precautionary principle is a strategic approach to managing potential risks when scientific understanding of a technology's full impact is incomplete. It is a key component of responsible innovation processes in biomimicry [7].

Biomimicry innovations, like any new technology, may have unintended consequences when introduced into complex social and ecological systems [7]. For instance, a biomimetic solution sustainable at a micro level, such as a biofuel inspired by photosynthesis, could lead to widespread deforestation if scaled up without careful systemic planning [8]. The precautionary principle dictates that in the face of such uncertain but potentially severe risks, a lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason to postpone cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation or harm to human health [7].

Responsible biomimicry practice requires the use of tools like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and systems thinking to evaluate potential risks and unintended consequences across the entire lifecycle of a product, from raw material sourcing to end-of-life management [8] [7].

Table 1: Core Ethical Frameworks in Biomimicry R&D

| Ethical Framework | Core Question | Application in Biomimicry R&D | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Ethics | Does the innovation respect nature's intrinsic value? | Adopting an ecocentric perspective; using "Respect for Life" principles; ensuring designs contribute to ecosystem health [8] [7]. | Overcoming anthropocentric bias; ensuring genuine sustainability, not just technical mimicry [9]. |

| Bioethics | Are the biological knowledge and resources used justly? | Implementing Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS); protecting Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK); ensuring ethical sourcing of biological models [8] [7]. | Preventing biopiracy; navigating intellectual property of nature; establishing equitable partnerships [8]. |

| Precautionary Principle | How do we manage uncertain risks? | Conducting systemic risk analyses; employing Life Cycle Assessment (LCA); adopting anticipatory governance and adaptive management [8] [7]. | Balancing innovation with caution; identifying second-order effects; avoiding paralysis by analysis [8]. |

Methodological Integration: From Principle to Practice

Experimental Protocols for Ethical Biomimicry Research

Translating ethical frameworks into actionable research protocols ensures that principles are embedded throughout the R&D lifecycle. The following methodologies provide a structured approach for researchers.

Protocol 1: Ethical Life Cycle Assessment (E-LCA) for Biomimetic Products

- Objective: To evaluate the environmental, social, and ethical impacts of a biomimetic product or material from raw material extraction to end-of-life.

- Methodology:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Define the assessment's purpose, system boundaries, and functional unit. Explicitly include ethical criteria such as sourcing impacts on biodiversity and potential social impacts on local communities [8].

- Inventory Analysis (LCI): Compile an inventory of relevant energy, material inputs, and environmental releases. Include data on the geographical origin of biological models and any associated Traditional Ecological Knowledge [8].

- Impact Assessment (LCIA): Assess the potential impacts using categories like resource depletion, ecosystem degradation, and human health. Incorporate a "Ethical Sourcing Score" to evaluate the fairness of benefit-sharing arrangements [8] [7].

- Interpretation: Analyze results to make informed, ethically-grounded decisions regarding design improvements, material selection, and end-of-life strategies (e.g., designing for disassembly, recycling, or safe biodegradation) [8].

Protocol 2: Systemic Risk Assessment for Novel Biomimetic Technologies

- Objective: To identify and evaluate potential unintended consequences of a biomimetic technology at micro (local), meso (industry), and macro (global) scales.

- Methodology:

- System Scoping: Map the core technology and its direct and indirect connections to ecological and socio-economic systems [8].

- Risk Identification: Brainstorm potential unintended consequences across different scales (e.g., local ecosystem disruption, market displacement, macro-level resource competition) [8] [7].

- Risk and Trade-off Analysis: Qualitatively or quantitatively assess the likelihood and severity of identified risks. Evaluate trade-offs where a positive impact at one level may cause a negative impact at another [8].

- Mitigation Strategy Development: Develop proactive measures to avoid, mitigate, or manage identified risks. This could include establishing monitoring programs, designing for closed-loop systems, or creating plans for a just transition for affected workers [8].

Visualization of an Ethical Biomimicry R&D Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a integrated workflow that embeds ethical considerations into each stage of the biomimetic research and development process.

Ethical R&D Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Ethical Biomimetic Research

This toolkit outlines key reagents and materials used in advanced biomimetic research, particularly in drug development and biotechnology, with an emphasis on ethically-sourced and life-friendly components.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions in Biomimetic Drug Development

| Research Reagent / Material | Natural Inspiration / Function | Ethical & Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-derived Organoids [5] | Used in 3D culture to create more physiologically relevant human tissue models for preclinical drug screening (e.g., engineered cardiac tissues). | Supports the 3Rs (Refinement, Reduction, Replacement) in animal testing [5]. Ethical sourcing of original cell lines and informed consent are paramount. |

| Peptidomimetics & Synthetic Peptides [10] | Small molecules or short synthetic peptides designed to mimic natural antimicrobial peptides (e.g., LL-37). | Aims to create stable, effective "armored" versions of natural defenses. Requires careful assessment of long-term ecological impact if released into the environment [10]. |

| Biomimetic Scaffolds (e.g., Collagen, Chitosan, Alginate) [6] | Natural polymers used as scaffolds in tissue engineering that mimic the extracellular matrix. | Prioritizes biocompatibility and biodegradability [6]. Sourcing should be sustainable (e.g., from fishery waste for chitin) and avoid depletion of natural stocks. |

| Cell Membrane-Camouflaged Nanoparticles [6] | Nanoparticles coated with natural cell membranes (e.g., from red blood cells) to evade the immune system and improve targeted drug delivery. | Uses natural human-derived components, raising questions about donor consent and the ethical sourcing of biological materials [6]. |

| Bio-inspired Adhesives (e.g., Polydopamine) [6] | Adhesives inspired by marine organisms like mussels and tubeworms for use in wet environments, including surgical applications. | Aims for water-resistant and potentially biodegradable alternatives to synthetic glues. Life cycle assessment is needed to ensure manufacturing is environmentally benign [6]. |

The ultimate ethical challenge for biomimicry is to transcend its utilitarian origins and become a practice that actively contributes to the regeneration of ecosystems, driven by an ecocentric worldview [8]. This requires more than just technical protocols; it demands a fundamental cognitive shift from a mindset of exploitation to one of deep integration and partnership with nature [11]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this means embedding the core frameworks of environmental ethics, bioethics, and the precautionary principle into every stage of their work—from initial observation of a biological model to the global deployment of a resulting technology.

By adopting interdisciplinary collaboration, holistic systems thinking, and responsible innovation processes, the field of biomimicry can fulfill its promise [7]. This approach ensures that the pursuit of innovation is guided by a commitment to sustainability, social equity, and a profound respect for the 3.8 billion years of evolutionary wisdom that nature embodies [11]. The frameworks and methodologies outlined in this whitepaper provide a roadmap for this transition, enabling the development of biomimetic solutions that are not only effective but also ethical, just, and regenerative.

Life's Principles are a set of design strategies derived from the observation of organisms and ecosystems that have survived and thrived on Earth for 3.8 billion years. These principles form the core of biomimicry, the practice of learning from and emulating nature’s designs to solve human challenges. For researchers and scientists in drug development and other advanced fields, these principles offer a robust framework for creating innovations that are not only effective but also inherently sustainable and life-friendly. The Biomimicry Life's Principles inform the Ethos and Measure components of biomimicry and serve as a tool for both ideation and evaluation, ensuring that projects are true expressions of biomimicry [12]. In the context of a broader thesis on bioethics, Life's Principles provide a tangible methodology for aligning technological development with ethical imperatives, ensuring that our innovations respect the natural systems from which they are inspired.

The urgency of integrating such a framework is underscored by the rapid growth of biomimetic research; an analysis of 74,359 publications reveals a staggering increase in activity, yet also highlights a reliance on a narrow set of animal taxa, suggesting an untapped potential for innovation through a more diverse and principled approach [13]. This guide provides a detailed exploration of the 27 strategies, their quantitative assessment methodologies, and their critical role in addressing the ethical considerations—such as respect for nature's intellectual property and the avoidance of unintended consequences—that are paramount in responsible research and development [7] [14].

The Framework of Life’s Principles

The Six Overarching Principles and Their 27 Strategies

The Biomimicry Life's Principles are categorized into six overarching principles, which collectively contain 27 specific strategies. These were abstracted from biological literature and translated into a generic design language to be usable by designers, scientists, and engineers. They are based on the recognition that all life is interconnected and subject to the same operating conditions, and thus have evolved winning strategies for sustainability [12]. The following table summarizes the complete set of 27 strategies as updated in 2024, providing a comprehensive reference for researchers.

Table 1: The Complete Set of 27 Biomimicry Life's Principles

| Overarching Principle | Specific Strategy | Technical Description |

|---|---|---|

| Evolve to Survive | Replicate Strategies that Work | Incorporate successful, time-tested biological strategies into designs. |

| Integrate the Unexpected | Build in flexibility and mechanisms to adapt to unforeseen changes. | |

| Reshuffle Information | Encourage the exchange and recombination of ideas and genetic information. | |

| Adapt to Changing Conditions | Incorporate Diversity | Leverage functional diversity to enhance resilience and performance. |

| Maintain Integrity through Self-Renewal | Continuously repair and renew components at multiple scales. | |

| Embody Resilience | Withstand and recover from disturbances without collapsing. | |

| Be Locally Attuned and Responsive | Leverage Cyclic Processes | Design for closed-loop systems with no waste. |

| Use Readily Available Materials and Energy | Utilize abundant, local resources to minimize energy expenditure. | |

| Use Feedback Loops | Incorporate continuous information flow to maintain system stability. | |

| Cultivate Cooperative Relationships | Foster synergies and mutualism between system components. | |

| Integrate Development with Growth | Self-Organize | Create structure and pattern through local interactions and decentralized control. |

| Build from the Bottom Up | Assemble complex systems from simple, modular units. | |

| Combine Modular and Nested Components | Design systems where modules operate at multiple scales. | |

| Be Resource Efficient (Material and Energy) | Use Low Energy Processes | Minimize energy consumption by using passive and efficient mechanisms. |

| Use Multi-Functional Design | Assign multiple functions to a single element to reduce material use. | |

| Recycle All Materials | Treat all outputs as inputs for another process. | |

| Fit Form to Function | Shape structures to optimally perform their intended task. | |

| Use Life-Friendly Chemistry | Build from a Small Subset of Elements | Prefer common, non-toxic elements in manufacturing and design. |

| Break Down Products into Benign Constituents | Ensure all byproducts are non-toxic and easily reassimilated. | |

| Do Chemistry in Water | Use water as a primary solvent in industrial and synthetic processes. | |

| Employ Elegant Processes | Minimize synthetic steps and use mild, efficient reaction conditions. |

The Ethical Imperative of Life's Principles

Life's Principles are more than a design checklist; they are a manifestation of a deeper ethical commitment. At its core, biomimicry proposes a shift from viewing nature as a resource to be exploited to recognizing it as a mentor offering billions of years of wisdom [14]. This shift is critical for bioethics in research, as it challenges the anthropocentric worldview—the human-centered perspective that often places human interests above all else. By rigorously applying Life's Principles, researchers can move towards a more ecocentric or biocentric perspective, where the well-being of the entire ecological community is considered [14]. This aligns with the "Respect for Life" principles developed by the Biomimicry Institute, which include recognizing interconnectedness, supporting biodiversity, using life-friendly materials, and engaging in mutual benefit with nature [7].

A key ethical challenge in biomimicry is the risk of instrumentalizing nature—reducing living organisms to mere sources of design inspiration without acknowledging their intrinsic value or complexity [14]. The superficial application of biological forms without adhering to the underlying processes and ethics can lead to "biomimetic greenwashing." Life's Principles serve as a benchmark to prevent this, ensuring that solutions are not just inspired by nature's forms but also follow its processes and overarching ethos, promoting truly regenerative, context-appropriate innovations [12]. This is particularly relevant in drug development, where the line between inspiration and exploitation of biological resources must be carefully managed with attention to fair and equitable benefit-sharing [7].

Quantitative Assessment of Biomimetic Performance

The BiomiMETRIC Assistance Tool

To move beyond qualitative assessment and enable rigorous, quantitative evaluation of how well a design or project aligns with Life's Principles, researchers have developed the BiomiMETRIC assistance tool. This tool complements standards like ISO 18458 by combining the principles of biomimetic design with the quantitative impact assessment methods used in Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) [15]. The core premise of BiomiMETRIC is to structure a quantitative assessment of biomimetic performance by linking Life's Principles to measurable environmental impact indicators. This addresses a significant weakness in the biomimetic design process, which has traditionally relied on qualitative checks during the performance assessment phase [15].

The BiomiMETRIC tool operationalizes the principles proposed by the Biomimicry Institute, such as "Use materials sparingly," "Do not exhaust resources," and "Do not pollute your nest," by connecting them to established LCA impact methods like ReCiPe 2016, Impact 2002+, and TRACI [15]. These methods use characterization factors to quantify impact categories. For instance, the climate change impact is measured in kg CO₂ equivalent, and resource depletion can be quantified in terms of antimony equivalent [15]. By prioritizing midpoint impact categories over more aggregated endpoint categories, BiomiMETRIC maintains scientific rigor and reduces uncertainty in the assessment [15].

Table 2: Linking Life's Principles to Quantitative LCA Impact Categories

| Life's Principle (Example) | Relevant LCA Impact Category | Quantitative Indicator (Example) |

|---|---|---|

| Use Materials Sparingly | Resource Depletion (Abiotic) | kg Sb (antimony) equivalent |

| Use Energy Efficiently | Global Warming Potential | kg CO₂ equivalent |

| Do Not Pollute Your Nest | Freshwater Ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DB equivalent |

| Remain in Dynamic Equilibrium | Acidification Potential | kg SO₂ equivalent |

| Use Waste as a Resource | Depletion of Abiotic Resources | kg Sb equivalent (for saved resources) |

Experimental Protocol for Applying BiomiMETRIC

The following workflow details the methodology for using the BiomiMETRIC tool in a research and development context, providing a reproducible experimental protocol.

Title: BiomiMETRIC Assessment Workflow

Protocol Steps:

- Define Project Scope and Function: Clearly articulate the primary function of the drug delivery system, material, or process under development. This aligns with the biomimetic design sequence where "function" is the central focus [15].

- Identify Relevant Life's Principles: Select the most applicable principles from the 27 Life's Principles. For a drug delivery nanoparticle, this might include "Use Life-Friendly Chemistry," "Be Resource Efficient," and "Break Down Products into Benign Constituents."

- Map Principles to LCA Impact Categories: Use a predefined matrix (as in Table 2) to link the selected Life's Principles to quantifiable LCA impact categories. For "Use Life-Friendly Chemistry," relevant categories could include Human Toxicity and Freshwater Ecotoxicity.

- Gather Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Data: Collect data on all material and energy inputs and environmental outputs across the entire life cycle of the project (raw material extraction, manufacturing, use, end-of-life). This data is the foundation for all calculations.

- Calculate Impact Scores: Using LCA software (e.g., openLCA, SimaPro) and the chosen impact method (e.g., ReCiPe 2016), compute the characterized impact scores for each category identified in Step 3.

- Calculate Biomimetic Performance Index (BPI): Aggregate the individual impact scores into a normalized composite index. This can be a weighted sum based on the relevance of each impact category to the selected Life's Principles, providing a single score for the project's overall biomimetic performance.

- Interpret Results and Redesign: Compare the BPI against a benchmark (e.g., a conventional product or a previous design iteration). A lower aggregate environmental impact and a higher BPI indicate stronger alignment with Life's Principles. Use these results to identify hotspots and inform a redesign feedback loop.

This protocol was applied in a comparative study of insulation materials, where BiomiMETRIC analysis revealed that stone wool had a higher biomimetic performance than cork, despite cork being a bio-based material, demonstrating the tool's ability to provide counter-intuitive, quantitative insights [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomimetic R&D

The practical application of Life's Principles in a research setting, particularly in drug development and materials science, requires a suite of conceptual and analytical tools. The following table details key "research reagents" – both conceptual frameworks and physical materials – that are essential for conducting rigorous, ethically-grounded biomimetic research.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Biomimetic Research & Development

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Utility | Application in Biomimetic R&D |

|---|---|---|

| AskNature Database | A free online database of biological strategies and their technological applications. | Serves as the primary resource for identifying biological models that solve a specific function (e.g., "how does nature achieve targeted delivery?"). It is recommended during the biomimetic design process to discover Nature's principles [15]. |

| Life's Principles Framework | The set of 27 strategies (see Table 1) used as an ideation and evaluation tool. | Provides ethical and sustainable design constraints during the ideation phase and serves as a qualitative checklist for evaluating concepts. |

| Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) | A quantitative methodology for assessing environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life. | Used within the BiomiMETRIC tool to quantitatively measure a project's alignment with Life's Principles, moving beyond qualitative claims to data-driven validation [15]. |

| ISO 18458 Standard | An international standard providing terminology, concepts, and a methodology for biomimetics. | Ensures consistency and rigor in communication and methodology across interdisciplinary teams in science and industry [15]. |

| Water-Soluble / Biodegradable Polymers | Physical materials (e.g., specific polysaccharides, polyesters) for drug encapsulation and delivery. | Enable the implementation of the "Do Chemistry in Water" and "Break Down into Benign Constituents" principles for creating life-friendly drug delivery vehicles. |

Ethical Considerations and Future Outlook

Navigating the Ethical Landscape

The integration of Life's Principles into research is inextricably linked to a broader bioethical discourse. Several critical ethical considerations must be actively managed:

- Intellectual Property and Benefit-Sharing: A primary ethical question revolves around the "intellectual property of nature." Commercializing innovations derived from nature's designs necessitates careful consideration of fair and equitable benefit-sharing, particularly with indigenous communities and countries of origin that are stewards of rich biodiversity [7] [16]. This is a key component of ethical biomimicry practice in business [7].

- Avoiding Reductionism: There is a risk of oversimplifying or misinterpreting biological strategies by focusing on isolated mechanisms while ignoring their broader ecological context. Ethical practice demands a deep ecological understanding and holistic systems thinking to avoid unintended consequences [14] [12].

- Equity and Access: As biomimetic technologies advance, it is vital to ensure that their benefits are equitably distributed and do not exacerbate existing social and economic inequalities. This requires deliberate policies for open innovation, knowledge sharing, and technology transfer to ensure solutions are accessible to those who need them most [14] [16].

The Path Forward: From Sustainability to Regeneration

The future of biomimetic research lies in moving beyond simply reducing harm towards creating technologies that are actively regenerative. Life's Principles provide the blueprint for this transition. However, current research shows a persistent taxonomic bias, with over 75% of biomimetic models drawn from the animal kingdom and a reliance on a narrow set of species, limiting the field's innovative potential [13]. Future efforts must prioritize stronger collaboration with biologists to integrate underutilized taxa and specify biological inspirations at the species level to enhance evolutionary insights [13]. By fully embracing the depth and breadth of Life's Principles, researchers and drug development professionals can usher in a new era of innovation that not only solves human health challenges but also contributes to the health of the planet, fulfilling the ultimate purpose of life: to create conditions conducive to life.

The field of biomimicry, defined as the practice of learning from and emulating nature's strategies to solve human challenges, is rapidly transforming research and development across disciplines, from medicine to materials science [6]. At its core, biomimicry presents a paradigm shift, proposing that nature should serve not merely as a resource to be exploited, but as a model, measure, and mentor [17] [18]. This philosophical foundation is intrinsically linked to a set of ethical principles often termed "Respect for Life Principles," which emphasize interconnectedness, biodiversity, and mutual benefit [14]. For researchers in drug development and other scientific fields, integrating these principles is not an abstract ideal but a practical necessity for conducting responsible and sustainable innovation. This guide provides a technical framework for embedding these bioethical considerations into biomimetic R&D, ensuring that our quest for inspiration from nature is conducted with respect for the complex, interconnected systems from which we learn.

The urgency of this ethical integration is underscored by a critical analysis of the field's current state. A comprehensive study analyzing 74,359 biomimetics publications reveals a significant reliance on a narrow set of biological models, with over 75% of inspiration drawn from animals and fewer than 23% of models specified at the species level [13]. This taxonomic bias risks overlooking vast reservoirs of biological genius and undermines the principle of respecting biodiversity. Furthermore, without a firm ethical grounding, biomimicry can inadvertently perpetuate a utilitarian view of nature, where biological systems are instrumentalized for human gain without reciprocal consideration [14]. This paper details methodologies and frameworks to align cutting-edge biomimetic research with the fundamental principles that allow life to thrive.

Quantitative Analysis of Biodiversity in Biomimetic Research

Systematic analysis of publication data provides a clear, quantitative picture of how biomimetics currently engages with biological biodiversity. Such analyses are crucial for establishing a baseline and measuring progress toward a more inclusive and respectful practice.

Taxonomic Distribution of Biological Models

An analysis of 31,776 biological models identified in biomimetics literature reveals distinct patterns in taxonomic representation. The following table summarizes the distribution of inspiration across the major kingdoms of life, illustrating a heavy bias toward certain groups.

Table 1: Kingdom-Level Distribution of Biological Models in Biomimetics Research

| Kingdom | Proportion of Biological Models | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Animalia | >75% (as of 2024) | Dominant source; primarily chordates (vertebrates) and arthropods (insects, spiders) [13]. |

| Plantae | ~16% | Early popularity; 679 species cited, showing greater utilized species richness than animals [13]. |

| Other Kingdoms | <9% (combined) | Includes Bacteria, Fungi, Protista, Archaea, and Viruses; consistently play a less influential role [13]. |

This data indicates that while the field draws inspiration from all kingdoms of life, the exploration is highly uneven. The recent surge in animal-based models coincides with the field's rapid growth but suggests a potential narrowing of exploratory focus [13].

Resolution and Breadth of Model Taxa

The depth of taxonomic identification in research publications is a key indicator of biological specificity. Analysis shows that a minority of biological models are resolved at the species level, with a preference for broader classifications.

Table 2: Taxonomic Resolution of 31,776 Identified Biological Models

| Taxonomic Rank | Percentage of Models | Cumulative Distinct Species |

|---|---|---|

| Species | 22.6% | 1,604 distinct species [13] |

| Genus | 7.1% | Information Missing |

| Family | 8.3% | Information Missing |

| Order | 9.2% | Information Missing |

| Class | 22.5% | Information Missing |

| Phylum | 24.9% | Information Missing |

| Kingdom | 5.4% | Information Missing |

This reliance on broad classifications can limit the field's capacity to leverage deep evolutionary insights. Species-level resolution is critical for understanding the precise adaptations and contextual pressures that shape a biological strategy, which is essential for robust and ethical translation into applications like pharmaceutical design [13].

The Ethical Framework: Life's Principles as a Guide for Research

The "Life's Principles" framework, derived from the strategies that have sustained life on Earth for 3.8 billion years, provides a concrete set of design guidelines for aligning biomimetic research with Respect for Life Principles [19] [17]. These principles can be directly operationalized within a research and development context.

The Six Overarching Life's Principles

The Biomimicry 3.8 framework distills nature's strategies into six overarching principles, each comprising more specific sub-principles [19]. For researchers, these serve as a checklist for evaluating the ethical and ecological alignment of their work.

- Evolve to Survive: This principle emphasizes replication of successful strategies, integration of the unexpected, and reshuffling of information. In a research context, this translates to iterative design processes and genetic algorithms that mimic evolutionary optimization [20].

- Adapt to Changing Conditions: Strategies include incorporating diversity, maintaining integrity through self-renewal, and embodying resilience. This is crucial for designing therapeutic systems that can adapt to in-vivo conditions or pathogen evolution.

- Be Locally Attuned and Responsive: This involves leveraging cyclic processes, using readily available materials and energy, cultivating cooperative relationships, and using feedback loops [19] [20]. For drug delivery systems, this could mean designing mechanisms that respond to specific local biochemical signals.

- Integrate Development with Growth: Key strategies are self-organization, building from the bottom-up, and combining modular and nested components [19]. This guides the fabrication of complex structures, such as scaffolds for tissue engineering, in a more efficient and less wasteful manner.

- Be Resource Efficient (Material and Energy): This principle mandates the use of low-energy processes, multi-functional design, recycling all materials, and fitting form to function [19]. This is directly applicable to sustainable lab practices and designing synthetic pathways that mimic the efficiency of biological chemistry, such as doing chemistry in water at ambient temperature [20].

- Use Life-Friendly Chemistry: This involves employing elegant, non-toxic processes, using a small subset of elements, doing chemistry in and with water, and breaking down products into benign constituents [19]. This is a fundamental directive for developing green chemistry protocols and biodegradable medical materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Operationalizing Ethics in Research

Translating ethical principles into laboratory practice requires specific tools and a shift in methodology. The following table details key research reagents and approaches inspired by biomimetic ethics.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Biomimicry in Drug Development

| Research Reagent / Material | Function | Ethical & Practical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-inspired Scaffolds (e.g., Collagen/Nanotube composites, alginate, chitosan) [6] | Tissue engineering; 3D cell culture models for drug testing. | Biodegradability, biocompatibility, and resemblance to original tissue promote natural cell growth and reduce environmental burden (Be Resource Efficient, Use Life-Friendly Chemistry) [6]. |

| Life-Friendly Solvents (e.g., Water-based systems) [20] | Replacement for petroleum-based solvents in synthesis and processing. | Reduces energy intensity, eliminates toxic waste, and utilizes renewable resources (Use Life-Friendly Chemistry) [20]. |

| Red Blood Cell (RBC) Membrane-Camouflaged Nanoparticles [6] | Drug delivery vehicle for targeted therapy. | Leverages biological mimicry for prolonged systemic circulation, reduced immune recognition, and improved biocompatibility (Be Locally Attuned and Responsive) [6]. |

| Polydopamine Coatings [6] | Surface modification to enhance hydrophilicity and functionality of materials. | Mimics mussel adhesive chemistry; a versatile, strong, and often more benign alternative to synthetic coatings (Use Life-Friendly Chemistry, Be Resource Efficient) [6]. |

| Actinia-like Micellar Nanocoagulants [6] | Water pollutant removal for sustainable lab waste management. | Core-shell structure mimics sea anemone trapping mechanism; provides a cost-efficient, effective method for treating contaminated water (Integrate Development with Growth, Be Locally Attuned) [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Ethical Biomimetic Research

Adhering to Respect for Life Principles requires integrating specific considerations and methodologies at each stage of the research pipeline. The following workflow diagram and accompanying protocol details outline a rigorous approach.

Diagram 1: Biomimetic Research Workflow

Protocol 1: Problem Definition & Bio-Ethical Scoping (Define & Biologize)

- Objective: To frame the research challenge in biological terms while incorporating ethical constraints from the outset.

- Procedure:

- Define Function, Not Just Form: Clearly articulate the core function your design must perform (e.g., "targeted drug delivery to inflamed tissues," not just "create a new nanoparticle") [17].

- Biologize the Context: Reframe the problem and its operating environment in biological terms. Consider the chemical, physical, and biological constraints of the final application environment (e.g., the human body, a wastewater stream) [17].

- Integrate Life's Principles as Constraints: Use the Life's Principles as a checklist during problem definition. For example, specify that the solution must "Use Life-Friendly Chemistry" or "Be Resource Efficient" as a non-negotiable design parameter [19] [20].

- Ethical Considerations: This stage prevents the narrow, problem-only focus that can lead to solutions with negative unintended consequences. It forces consideration of the full life cycle of the research output.

- Objective: To identify biological models while respecting biodiversity and leveraging evolutionary insights.

- Procedure:

- Discover Beyond Iconic Models: Actively search for biological models beyond the well-known, iconic species (e.g., geckos, sharks). Utilize databases and biological literature to explore underutilized taxa, including plants, fungi, and bacteria [13].

- Employ a Multi-Model, Comparative Approach: To leverage evolutionary biology, select multiple biological models that solve the same problem in different ecological contexts. This comparative method can reveal the core principles of the solution shaped by different selective pressures [13].

- Abstract at the Species Level: Where possible, study the biological strategy at the species level to understand the specific adaptation in its ecological context. Abstract the underlying physical or chemical mechanism, not just the superficial form [13] [17].

- Ethical Considerations: This protocol directly addresses the taxonomic bias in the field, respecting biodiversity by valuing a wider array of life forms. The deep contextual understanding gained helps avoid reductionism and misinterpretation of the biological strategy [14].

Protocol 3: Emulation and Rigorous Evaluation (Emulate & Evaluate)

- Objective: To translate biological strategies into technical applications and evaluate them against both performance and ethical criteria.

- Procedure:

- Emulate with Sustainable Materials: In the design and prototyping phase, prioritize the use of bio-inspired, life-friendly materials identified in the Scientist's Toolkit (e.g., bio-polymers, water-based chemistry) [6] [20].

- Evaluate with Dual Metrics: Establish clear evaluation metrics for both performance (e.g., drug delivery efficacy, material strength) and sustainability/ethics (e.g., biodegradability, toxicity, energy consumption over life cycle) [17] [14].

- Conduct a Precautionary Impact Assessment: Before scaling, conduct a holistic assessment of potential unintended ecological and social consequences. This includes life cycle assessment (LCA) and consideration of equity and access to the resulting technology [14].

- Ethical Considerations: This stage ensures that the emulation of nature's forms is coupled with emulation of nature's processes and ethics, moving beyond superficial mimicry to truly regenerative design [19]. It mitigates the risks of greenwashing and instrumentalization of nature [14].

Integrating Respect for Life Principles—interconnectedness, biodiversity, and mutual benefit—into biomimetic research is not a constraint on innovation but a pathway to more robust, sustainable, and truly transformative solutions. For researchers in drug development and related fields, the frameworks, data, and protocols provided here offer a concrete starting point. By consciously expanding the taxonomic breadth of our biological models, adhering to the design principles that life itself uses, and rigorously evaluating our work against ethical metrics, we can shift the paradigm. The goal is to create a research culture that not only learns from nature's genius but also honors its source, ensuring that our advancements contribute to a world that is more resilient, adaptive, and conducive to all life.

The fields of biology-inspired innovation have generated multiple terms that are often used interchangeably but embody fundamentally distinct philosophies and objectives. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these distinctions is critical for aligning methodological approaches with intended outcomes, particularly when operating within a bioethical framework. This technical guide examines the core distinctions between biomimicry and biomimetics, two disciplines that differ significantly in their underlying motivations, ethical considerations, and applications in therapeutic development.

While both approaches derive inspiration from biological models, biomimetics primarily focuses on the technical imitation of biological structures and processes to advance technological innovation, often without explicit sustainability considerations [7]. In contrast, biomimicry emphasizes sustainability and respect for life as core principles, adopting a holistic, systems-thinking approach that considers the interconnectedness of life and aims to create solutions that fit harmoniously within natural systems [7]. This distinction carries profound implications for research design, ethical evaluation, and ultimate application in drug discovery and development pipelines.

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Biomimetics and Biomimicry

| Aspect | Biomimetics | Biomimicry |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Technical imitation of biological structures and processes [7] | Sustainable innovation through nature's guidance [21] |

| Core Philosophy | Problem-solving through biological models | Respect for life, holistic systems thinking [7] |

| Historical Origin | Coined by Otto H. Schmitt (1969), biomedical engineering [22] | Coined by Janine Benyus, natural sciences [22] |

| Sustainability | Not inherently considered [7] | Central design principle [21] [7] |

| Ethical Framework | Often implicit or secondary | Explicitly integrated (Respect for Life principles) [7] |

Conceptual and Historical Foundations

Etymological and Philosophical Origins

The terminological divergence between biomimetics and biomimicry reflects their distinct historical pathways and philosophical underpinnings. The term "biomimetics" was coined approximately in 1969 by Otto H. Schmitt, a pioneer in biomedical engineering, deriving from the Greek words "bios" (life) and "mimesis" (imitate) [22]. This emerging discipline was predominantly rooted in engineering and focused on extracting biological principles for technological application without necessarily considering ecological context.

The field of "biomimicry" was formally named by Janine Benyus, a natural sciences writer, who positioned it as a revolutionary approach to innovation that seeks sustainable solutions by emulating nature's time-tested patterns and strategies [21]. Benyus specifically associated biomimicry with sustainability, emphasizing that unlike previous revolutions, "it is not about stealing nature's secrets, ruling over it, or domesticating it" but rather "invites humility, encouraging humans to approach nature as part of it" [21]. This fundamental philosophical distinction continues to inform the practice and ethical orientation of each field.

Disciplinary Positioning and Evolution

The historical context of these approaches reveals how their divergent goals emerged from different professional environments. Bionics (another related term) was developed by Jack Steele, an engineer and psychiatrist in the Air Force's Aerospace Medical Division, with initial emphasis on systems design and neuroanatomy [22]. Biomimetics emerged from biomedical engineering, with Schmitt's early work concentrating on mimicking the electrical action of a nerve [22]. In contrast, biomimicry draws inspiration from principles of ecologically informed design and positions itself within sustainability science and ecological design frameworks [22].

This historical analysis clarifies that these movements "historically have had different goals and underlying connotations: innovation for the purpose of technological advancement, and innovation for the purpose of social, environmental, and economic sustainability" [22]. For drug development professionals, this historical context is valuable for understanding how these approaches might be strategically deployed within research and development pipelines with different ultimate objectives.

Ethical Dimensions in Research and Application

Biomimicry's Embedded Ethical Framework

Biomimicry incorporates an explicit ethical dimension that distinguishes it from purely technically focused approaches. This ethical framework is operationalized through principles such as the "Respect for Life Principles" developed by the Biomimicry Institute, which include "recognizing the interconnectedness of all life, supporting biodiversity, using life-friendly materials and processes, and engaging in mutual benefit with nature" [7]. These principles provide tangible guidance for researchers seeking to align their work with sustainable and ethical outcomes.

The ethical practice of biomimicry requires careful consideration of potential ecological impacts through tools like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which evaluates environmental performance across a product's entire lifespan [7]. Additionally, it raises questions about "intellectual property of nature," specifically regarding whether natural designs can or should be patented, and if so, how benefits should be shared with indigenous communities and countries of origin [7]. These considerations are particularly relevant in drug discovery, where biological resources may form the basis of profitable therapeutics.

Ethical Challenges in Biomimetics Application

While biomimetics does not inherently incorporate the explicit ethical framework of biomimicry, its application in pharmaceutical research nonetheless raises significant ethical considerations that researchers must address. The potential for unintended consequences when introducing new technologies based on biological models into complex systems requires careful risk assessment and ongoing monitoring [7]. Furthermore, the dual-use dilemma applies equally to biomimetics, where the same biological insights that could lead to therapeutic breakthroughs might also be applied to harmful purposes without appropriate ethical oversight [7].

The ethical ambiguity in biomimetic technologies stems from their potential to "reproduce nature-like artefacts, systems and environments" that could ultimately replace rather than complement non-artificial nature [23]. This raises philosophical questions about the relationship between nature and technology that are particularly salient in drug development, where the line between natural and artificial therapeutic interventions is increasingly blurred.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Biomimetic Approaches in Cardiovascular Research

The application of biomimetic principles in drug discovery is particularly advanced in cardiovascular disease research, which remains the leading cause of death worldwide despite massive investment in drug discovery [5]. Traditional approaches have relied heavily on animal models, particularly rodents, which have significant limitations including "fundamental species differences," lack of long-standing cardiac pathology, and rare consideration of concomitant diseases like diabetes [5].

Biomimetic innovations have emerged to address these limitations through advanced in vitro engineered cardiac tissues that "aim to resemble human heart morphology and function" and have been "implemented in disease modelling, compound testing, and patient-specific screening" [5]. These systems attempt to replicate the complex loading environment of native cardiomyocytes, which "experience static and cyclic tension, as well as shear stresses" [5]. The technological focus of biomimetics is evident in these sophisticated tissue engineering approaches that prioritize physiological accuracy without explicit sustainability considerations.

The Shift Toward 3D Culture Systems

A significant advancement in both biomimetic and biomimicry-inspired drug discovery has been the transition from two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) culture systems. "Numerous studies have shown myocyte cell behaviour to be much more physiologically relevant in 3D culture compared to 2D culture," highlighting the advantages of using 3D-based models for preclinical drug screening [5]. This technological evolution represents a more accurate imitation of natural biological systems—a goal shared by both approaches, though potentially for different ultimate purposes.

The development of these systems faces significant challenges, as "standard matrices of Matrigel or other biologically derived gels lack the structural, chemical, and biochemical control needed to mimic specific tissues" [5]. This limitation has driven innovation in biomimetic material science, creating more sophisticated scaffolds that better replicate the native extracellular matrix. The FDA's Modernization Act 2.0, which overturned previous mandates for animal testing in drug development, has further accelerated adoption of these advanced models [5].

Table 2: Biomimetic/Biomimicry Applications in Drug Development Workflows

| Application Area | Traditional Approach | Bio-inspired Advanced Model | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Toxicity Screening | 2D cell culture, animal models | 3D engineered cardiac tissues [5] | More physiologically relevant cell behavior [5] |

| Disease Modeling | Rodent models with species differences | Human iPSC-derived organoids [5] | Human-specific pathology, patient-specific screening [5] |

| Compound Testing | Well-plate culture techniques | Microfluidic or organ-on-a-chip technologies [5] | High-throughput, complex microenvironment mimicry [5] |

| Pathophysiological Study | Isolated factor analysis | Systems biology approaches | Understanding of interconnected biological networks |

Experimental Protocols for Cardiac Tissue Engineering

The development of biomimetic cardiac tissues for drug screening involves sophisticated protocols that balance biological fidelity with practical utility. The following methodology outlines key considerations for creating engineered cardiac tissues that mimic native heart tissue for pharmaceutical testing:

Cell Source Selection: Utilize human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes to create human-relevant models while adhering to 3Rs principles (refinement, reduction, and replacement of animal studies) [5].

Scaffold Fabrication: Employ advanced biomaterials that provide structural, chemical, and biochemical control beyond traditional Matrigel, creating defined microenvironments that mimic specific tissue properties [5].

Mechanical Conditioning: Apply complex loading environments that replicate the static and cyclic tension, as well as shear stresses experienced by native cardiomyocytes [5]. This is typically achieved through bioreactor systems that provide controlled mechanical stimulation.

Functional Assessment: Implement multiparameter readouts including electrophysiological measurements (microelectrode arrays), contractility analysis (video-based tracking), and biochemical signaling profiling to comprehensively evaluate tissue function and drug responses.

Validation Against Clinical Data: Correlate in vitro model responses with known clinical outcomes to establish predictive validity, focusing particularly on cardiotoxicity endpoints that have previously led to drug attrition [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The implementation of biomimetic and biomimicry approaches requires specialized materials and reagents that enable the faithful reproduction of biological principles in experimental systems. The following table details key resources used in advanced bio-inspired research, particularly in cardiovascular drug discovery applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bio-inspired Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Human iPSCs | Patient-specific disease modeling; avoids species-specific differences [5] | Generating biologically relevant cardiomyocytes for cardiac toxicity screening [5] |

| Advanced Biomaterial Scaffolds | Provide structural, chemical, and biochemical control to mimic native extracellular matrix [5] | 3D engineered cardiac tissues that better replicate in vivo microenvironment [5] |

| Tissue-specific Matrices | Replace traditional biologically derived gels (e.g., Matrigel) with defined composition | Creating reproducible microenvironments for organoid development |

| Microfluidic Chips | Enable precise fluid control and mechanical stimulation; high-throughput capability [5] | Organ-on-a-chip technologies for predictive ADMET screening |

| Biosensors | Real-time monitoring of metabolic activity, electrophysiology, and contractility | Functional assessment of engineered tissues during compound testing |

The distinction between biomimetics and biomimicry represents more than mere semantic differences—it reflects fundamentally divergent approaches to biological inspiration with significant implications for drug discovery and development. Biomimetics offers powerful tools for creating technologically sophisticated models that enhance the physiological relevance of preclinical screening, potentially reducing late-stage drug attrition due to efficacy failures or unexpected toxicities [5]. Meanwhile, biomimicry provides an ethical framework that emphasizes sustainability, life-friendly materials, and consideration of broader ecological impacts [7].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic integration of both approaches offers a pathway to more ethical, effective, and sustainable innovation. Biomimetic technologies can address the "limited predictability and transferability of preclinical research to human patients" [5], while biomimicry's ethical principles can guide responsible innovation that respects biological systems and promotes equitable benefit-sharing. As the field advances, this integrated approach will be essential for addressing complex challenges in cardiovascular medicine and beyond while aligning pharmaceutical innovation with broader societal and environmental values.

From Principle to Practice: Ethical Methodologies for Biomimetic Drug Development

System-Level Biomimicry represents a transformative approach to research and development that moves beyond imitating discrete natural forms or processes. Instead, it seeks to emulate the overarching patterns, strategies, and performance standards of resilient ecosystems [24]. This paper focuses specifically on the application of Ecological Performance Standards (EPS) within R&D, framing this methodology as a core component of a broader bioethical framework for scientific innovation. A bioethical perspective in biomimicry development research demands that we move beyond a purely utilitarian relationship with nature—one of extraction and domination—and toward a relationship based on cooperation, respect, and a commitment to the preservation of life [2]. EPS operationalizes this ethic by challenging researchers to ask not "How can we minimize our harm?" but rather "How can our R&D activities contribute to the health and resilience of the local ecosystem, becoming functionally indistinguishable from nature?" [24]. This shift from a reductionist to a holistic, systems-level perspective is crucial for addressing complex 21st-century challenges in fields ranging from materials science to drug development, ensuring that our technological advancements align with the ecological principles that have sustained life for 3.8 billion years.

Core Principles and Methodologies of Ecological Performance Standards

Defining Ecological Performance Standards

Ecological Performance Standards (EPS) represent a rigorous, metrics-driven framework within system-level biomimicry. Building on the regenerative design agenda, EPS proposes a fundamental shift in design baselines: instead of using conventional or "less bad" human design as a benchmark, it uses the functional performance of a mature, resilient ecosystem as the target [24]. The core process involves quantifying the ecosystem services—such as water purification, nutrient cycling, climate regulation, and habitat provision—that would be generated by an intact, pre-development ecosystem in a specific location. These quantified metrics then become the mandatory performance standards for the R&D project or built-environment asset, establishing a goal of creating designs that are "functionally indistinguishable" from nature [24].

This approach is inherently place-based and context-specific, acknowledging that a successful ecological strategy in one biome may be maladaptive in another. This principle is mirrored in the Genius of Place biomimetic tool, which involves a detailed investigation of the local ecosystem to identify the key strategies and mechanisms that native organisms have evolved to thrive in that specific environment [24]. For instance, organisms in an arid environment will have vastly different water retention and thermal regulation strategies than those in a tropical rainforest. A bioethically-grounded R&D process must therefore be locally attuned and responsive, respecting the unique biological and cultural context in which it operates.

The "Life's Principles" as a Guiding Framework

Underpinning the successful implementation of EPS are "Life's Principles"—a set of six overarching design patterns and strategies distilled from the study of successful organisms and ecosystems [24]. These principles provide a comprehensive checklist for evaluating the ecological and ethical alignment of an R&D project. The table below summarizes these principles and their implications for R&D.

Table 1: Life's Principles as a Framework for Bio-Inspired R&D

| Overarching Principle | Key Sub-Elements | Implications for R&D |

|---|---|---|

| Evolve to Survive | Replicate, diversify, incorporate mistakes | Design for iterative adaptation and continuous learning; build in feedback loops. |

| Adapt to Changing Conditions | Incorporate diversity, maintain integrity, embody resilience | Create solutions that are robust, flexible, and "safe-to-fail". |

| Be Locally Attuned & Responsive | Use readily available materials and energy, leverage feedback loops, cultivate cooperative relationships | Source locally; design for circularity; foster interdisciplinary collaboration. |

| Integrate Development with Growth | Self-organize, build from the bottom-up, combine modular components | Design modular systems; use scalable, distributed manufacturing. |

| Be Resource Efficient | Use multi-functional design, recycle all materials, use low-energy processes | Minimize waste and energy input; design for disassembly and upcycling. |

| Use Life-Friendly Chemistry | Use water-based chemistry, break down into benign constituents, build selectiveity | Avoid toxic solvents and persistent pollutants; prefer green chemistry. |

The bioethical imperative is clear: for an innovation to be truly sustainable and responsible, it should, as a holistic system, embody all of these principles, not just one or two in isolation [24]. This multi-level, principle-based approach is the most effective path to achieving solutions with truly sustainable performance [21].

Quantitative Frameworks and Data Analysis for EPS

The successful application of EPS in R&D requires moving from qualitative inspiration to quantitative benchmarking. This involves establishing measurable targets derived from ecosystem functioning.

Table 2: Exemplar Ecological Performance Standards for R&D Projects

| Ecosystem Service Category | Quantitative Performance Metric | Baseline (Pre-Development Ecosystem) | R&D Project Target | Measurement Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Regulation | Stormwater retention capacity (m³/ha/year) | 95% of annual rainfall retained/infiltrated [24] | ≥ 95% retention | Continuous monitoring of inflow/outflow; soil moisture sensing. |

| Carbon Sequestration | Net carbon fixed (kg CO₂eq/m²/year) | 0.5 - 2 kg CO₂eq/m²/year (temperate forest) [24] | ≥ 0.5 kg CO₂eq/m²/year | Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) combined with biomass carbon accounting. |

| Material Cycling | % of material flow closed-loop (biodegraded/upcycled) | >99% in mature ecosystems [24] | >95% closed-loop | Material Flow Analysis (MFA) tracking all inputs and outputs. |

| Biodiversity Support | Habitat unit value (HU) per area | 1.0 HU (reference ecosystem) [24] | ≥ 1.0 HU | Species richness and abundance surveys compared to reference. |

Recent bibliometric analysis reveals a sharp increase in scholarly attention to bio-based materials, underscoring their growing relevance. An analysis of 1247 research articles from 2019 to 2024 shows a significant rise in publications focusing on the energy absorption mechanisms of bio-inspired structures, indicating a maturation of the field and a growing body of quantitative data available for setting robust EPS [25].

Experimental Protocols for Bio-Inspired Material Development

A critical area for applying EPS in R&D is the development of new materials. The following protocol outlines a methodology for creating lightweight, high-strength, energy-absorbing materials inspired by natural structures, directly contributing to resource efficiency and resilience.

Protocol: Developing Bio-Inspired Composite Materials for Impact Resistance

1. Bio-Inspiration and Abstraction:

- Identify Model Organisms: Select biological models with proven mechanical excellence. Key models include:

- Nacre (Mother of Pearl): For its "brick-and-mortar" microstructure, providing high toughness and crack deflection [25].

- Beetle Elytra: For its lightweight, sandwich structure with high compressive strength [25].

- Bamboo Culm: For its functionally graded, hollow cylindrical structure optimized for flexural strength [25].

- Abstract the Design Principle: Translate the biological observation into an engineering design principle. For example, abstract nacre's structure into a "high-aspect-ratio platelet composite architecture with compliant interfacial layers."

2. Modeling and Simulation: