Biomimetic Self-Assembly: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Advanced Applications in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Engineering

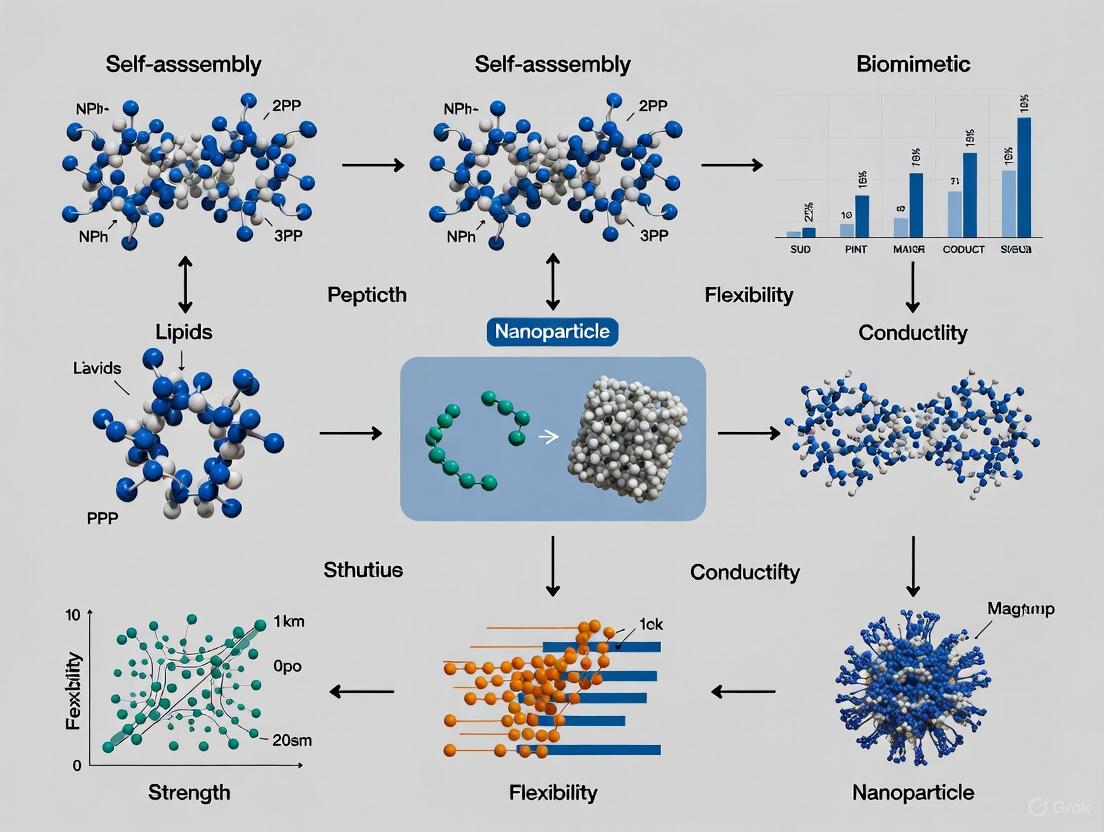

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the self-assembly properties of biomimetic materials, exploring the fundamental mechanisms inspired by natural processes and their transformative applications in biomedicine.

Biomimetic Self-Assembly: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Advanced Applications in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the self-assembly properties of biomimetic materials, exploring the fundamental mechanisms inspired by natural processes and their transformative applications in biomedicine. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it systematically covers foundational principles, advanced methodological approaches for drug delivery systems, troubleshooting of common challenges, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing the latest research, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging biomimetic self-assembly to develop next-generation therapeutic platforms, intelligent precision assembly modes, and multifunctional biomedical coatings with enhanced efficacy and biocompatibility.

Nature's Blueprint: Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms of Biomimetic Self-Assembly

Biomimetic self-assembly represents a paradigm shift in materials science, leveraging nature's evolutionary-optimized principles to create complex, functional structures from elementary building blocks. This technical guide delves into the core mechanisms, design principles, and experimental methodologies underpinning biomimetic self-assembling systems. By examining natural prototypes—from viral capsids to cellular matrices—we extract fundamental rules governing bottom-up organization and apply these principles to engineer advanced materials with tailored properties. Framed within broader research on self-assembly properties of biomimetic materials, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with quantitative frameworks, standardized protocols, and visualization tools to advance this transformative interdisciplinary field.

Fundamental Principles and Biological Inspiration

Biomimetic self-assembly is defined as the autonomous organization of components into patterned structures or functional systems without external intervention, inspired by biological processes [1]. This approach stands in stark contrast to traditional top-down manufacturing, instead leveraging nature's bottom-up strategies where entropy and thermodynamic driving forces guide organization [1]. Biological systems demonstrate remarkable self-assembling capabilities, from the precise folding of proteins into three-dimensional functional structures to the complex formation of viral capsids from protein subunits [1]. These natural processes share common elements: structured particles, specific binding forces, controlled environmental conditions, and entropy-driven forces that collectively enable spontaneous organization into complex architectures.

The fundamental distinction between self-assembly and related processes lies in their pathways and constraints. Self-assembly typically occurs through parallel processes where multiple components spontaneously organize simultaneously, while self-folding represents a constrained form of self-assembly where bending and binding occur at specific points within building blocks, often through serial processes [1]. In practice, hybrid processes frequently emerge, such as template-assisted self-assembly where components are tethered to templates that restrict their interaction possibilities, combining aspects of both self-assembly and self-folding [1]. This is exemplified in RNA-tethered viral capsomeres, where the template introduces serial aspects into the parallel assembly process [1].

Natural systems provide exquisite models for biomimetic design. The self-assembly of viral capsids demonstrates how identical protein subunits can efficiently form highly symmetric, stable containers for genetic material [1]. Similarly, keratin structures in avian feathers achieve remarkable mechanical properties through disulfide cross-links that preserve secondary structure and facilitate specific assembly pathways [2]. These biological systems share common design principles: hierarchical organization across multiple length scales, specific molecular recognition capabilities, and energy-efficient assembly pathways that minimize external intervention requirements.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Self-Organization Processes

| Process Type | Assembly Pathway | External Guidance | Biological Analogues | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Assembly | Parallel | None | Viral capsid formation, ribosome formation | Spontaneous organization of autonomous components |

| Self-Folding | Serial | None | Protein folding, wing-unfolding in beetles | Bending and binding at specific points within components |

| Template-Assisted Self-Assembly | Hybrid (Serial/Parallel) | Template scaffolding | RNA-tethered viral capsomeres | Components constrained by tethering to templates |

| Human-Guided Serial Folding | Serial | Intelligent external force | None | Robotic or human-directed folding along specific pathways |

Quantitative Performance Metrics of Biomimetic Materials

The translation of biological design principles into engineered materials has yielded remarkable advances in material performance. Biomimetic approaches enable the creation of materials with enhanced mechanical properties, environmental responsiveness, and multifunctionality that often surpass conventional engineering materials. These performance enhancements are quantified through standardized metrics across mechanical, functional, and sustainability domains, providing researchers with benchmark values for material development and optimization.

Recent breakthroughs in biomass-derived polymers demonstrate the efficacy of biomimetic self-assembly strategies. A novel self-reinforcing polyester material (PAOM) derived from lignin and soybeans incorporates aromatic π-conjugated vinylidene structures that enable performance enhancement under service conditions through a [2+2]-cycloaddition mechanism [3]. This biomimetic approach results in exceptional property enhancements, with tensile strength increasing to 103 MPa, elongation at break reaching 560%, and anti-ultraviolet efficiency of 73% - representing improvements of 61%, 201%, and 9% respectively over conventional materials [3]. These metrics significantly exceed those of most petroleum-based engineered plastics while maintaining full recyclability.

Hierarchical porous structures inspired by natural materials like bone, pomelo peel, and honeycomb configurations exhibit exceptional energy absorption properties critical for lightweight engineering applications [4]. Bio-inspired honeycomb structures achieve specific energy absorption values of 25.8-41.3 kJ/kg, substantially outperforming conventional hexagonal honeycombs (16.1-29.5 kJ/kg) [4]. Similarly, multilayer tube structures modeled after bamboo and horsetail plants demonstrate progressive collapse mechanisms with crush force efficiency (CFE) values of 0.68-0.87, compared to 0.55-0.65 for single-cell tubes, indicating more stable and efficient energy dissipation [4]. These quantitative improvements highlight the performance advantages attainable through biomimetic design principles.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Biomimetic Materials Versus Conventional Counterparts

| Material System | Key Performance Metrics | Biomimetic Materials | Conventional Materials | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Reinforcing Polyester (PAOM) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | 103 | 64 | +61% |

| Elongation at Break (%) | 560 | 186 | +201% | |

| Anti-UV Efficiency (%) | 73 | 67 | +9% | |

| Bio-inspired Honeycombs | Specific Energy Absorption (kJ/kg) | 25.8-41.3 | 16.1-29.5 | +60% (max) |

| Multilayer Tubes | Crush Force Efficiency (CFE) | 0.68-0.87 | 0.55-0.65 | +58% (max) |

| Biomimetic Porous Adsorbents | Heavy Metal Removal Efficiency (%) | 90.27 (BSA) | 70-85 | +15% |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Biological Template-Directed Synthesis

Biological tissue templating utilizes native biological structures as scaffolds for material synthesis, preserving their intricate architectural features. The protocol begins with template selection and preparation: plant-derived architectures (cotton fibers, lotus roots, cane leaves) or microbial templates (yeast, bacteria) are cleaned and subjected to surface functionalization [5]. For cotton fiber templates, the methodology involves hydrothermal in situ growth on Al2O3 fiber surfaces to engineer hierarchical microporous 3D architectures of LDH (layered double hydroxides)/Al2O3 composites [5]. The specific protocol entails immersing the biological template in precursor solutions (e.g., 0.1M Al(NO₃)₃ for 24 hours), followed by controlled calcination at 400-600°C in an inert atmosphere to remove the organic template while preserving the microstructural morphology [5]. This approach yields materials with high specific surface areas (documented up to 90.27% adsorption efficiency for bovine serum albumin) and tailored pore size distributions ranging from micropores (tens of micrometers) to macroporous frameworks (hundreds of micrometers) [5].

For microbial templating, urease-producing bacteria are employed in microbially induced carbonate precipitation. The protocol involves cultivating bacterial colonies in a nutrient-rich medium (e.g., 5g/L peptone, 3g/L beef extract) at 30°C for 24 hours, then suspending the cells in a solution containing urea (20g/L) and calcium chloride (25g/L) [5]. Heavy metal ions (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) are introduced to coordinate with carbonate ions, forming hybrid adsorbents through a 7-day incubation period. The resulting materials demonstrate exceptional adsorption capacity for heavy metals through combined electrostatic attraction and chemical complexation mechanisms, maintaining performance through multiple regeneration cycles [5].

Biomimetic Mineralization Techniques

Biomimetic mineralization employs biological macromolecules to control the assembly of inorganic materials into mineralized structures, mimicking natural processes like bone and tooth formation [5]. A standardized protocol involves preparing an aqueous solution of organic matrix macromolecules (e.g., collagen, chitin, or synthetic polypeptides) at 1-5 mg/mL concentration, followed by dropwise addition of inorganic precursors (e.g., CaCl₂ and Na₂HPO₄ for hydroxyapatite) under constant stirring at physiological pH (7.4) and temperature (37°C) [5]. The mineralization process proceeds for 24-72 hours, with morphological control achieved through modulation of ion concentration, temperature, and macromolecular templates. This bottom-up approach enables fabrication of porous nanomaterials with tunable morphology and dimensions, exhibiting enhanced mechanical properties including high elastic modulus and hardness [5].

Molecular Self-Assembly of Synthetic Polymers

The molecular self-assembly of keratin-based biomaterials exemplifies protein-derived approaches. The protocol begins with keratin extraction from poultry feathers using ionic liquid-based treatment or reduction processes that preserve the protein's secondary structure [2]. Critical to this process is maintaining disulfide crosslinks that enable the formation of homogeneous gels indicative of successful structure preservation [2]. The extracted keratin (at 5-10% w/v concentration) is dissolved in appropriate solvents (e.g., hexafluoroisopropanol or aqueous urea solutions), followed by solvent casting or electrospinning to create fibrous networks. Self-assembly occurs through controlled precipitation in anti-solvents or pH adjustment, resulting in materials that mimic the mechanical properties of native feathers—specifically designed to withstand flexure and lateral buckling at low thicknesses [2].

Visualization of Biomimetic Self-Assembly Pathways

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate key pathways and relationships in biomimetic self-assembly processes. The color palette complies with the specified requirements, ensuring sufficient contrast for accessibility.

Diagram 1: Biomimetic Self-Assembly Workflow illustrates the conceptual pathway from natural systems observation to functional structures creation through self-assembly processes.

Diagram 2: Self-Assembly Pathway Classification delineates the three primary pathways through which building blocks organize into functional structures.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of biomimetic self-assembly protocols requires specific reagents and materials that enable replication of biological design principles in synthetic systems. The following toolkit details essential components, their functions, and application contexts to facilitate experimental design and reproduction of results.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biomimetic Self-Assembly

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids | Keratin extraction with structure preservation | Feather keratin extraction [2] | Preserves disulfide crosslinks, maintains secondary structure |

| Hydroxyethylated Soy Isoflavone Monomer (DDF–OH) | Provides aromatic π-conjugated vinylidene structures | Self-reinforcing polyester materials [3] | Enables [2+2]-cycloaddition, enhances mechanical properties |

| Biological Templates (Plant/Microbial) | Structural scaffolds for biomimetic synthesis | Hierarchical porous materials [5] | Provides optimized architectures, controlled porosity |

| Polyelectrolytes (PDDA/PAA) | Surface modification for biomimetic mineralization | Yeast cell templating [5] | Enables layer-by-layer assembly, controls mineralization |

| Urease-Producing Bacteria | Microbially-induced carbonate precipitation | Heavy metal adsorbents [5] | Enables eco-friendly material synthesis, wastewater treatment |

| Ru-TiO₂/PC Composite | Photocatalytic functionality | Biomimetic photocatalysts [5] | Enhances visible-light absorption, improves electron-hole separation |

The selection of appropriate reagents must align with the targeted biomimetic principle and desired material properties. For structural applications requiring high strength and damage tolerance, reagents enabling π-π stacking interactions (such as DDF–OH) are critical for creating physically cross-linked networks that enhance chain segment friction and molecular dynamic volume [3]. For environmental applications including filtration or adsorption, biological templates with hierarchical porosity combined with surface modification agents enable creation of materials with superior selectivity and capacity [5]. In all cases, biomass-derived precursors align with sustainability objectives while maintaining performance requirements comparable to petroleum-based alternatives.

Biomimetic self-assembly represents a transformative approach to materials design, translating evolutionary-optimized biological principles into engineering solutions. This technical guide has established fundamental frameworks, quantitative metrics, standardized protocols, and visualization tools to advance research in this interdisciplinary domain. The integration of biomimetic principles with materials science enables creation of systems with enhanced performance, sustainability, and functionality across biomedical, environmental, and energy applications. As research progresses, the convergence of biological design rules with synthetic systems promises to unlock new generations of adaptive, self-repairing, and intelligent materials that address pressing global challenges while operating in harmony with natural systems.

In biomimetic materials research, the rational design of functional systems relies on mastering fundamental non-covalent interactions that drive molecular self-assembly. Hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and hydrophobic effects represent three cornerstone mechanisms governing the spontaneous organization of molecular building blocks into sophisticated architectures mirroring biological complexity. These directional, reversible, and synergistic interactions enable the bottom-up construction of materials with precise structural control and responsive functionalities, making them indispensable in applications ranging from targeted drug delivery to adaptive tissue engineering. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these key interaction mechanisms, focusing on their physical origins, quantitative characterization, and exploitation in biomimetic material design, particularly for pharmaceutical and therapeutic applications.

Hydrogen Bonding

Fundamental Principles and Energetics

Hydrogen bonding (H-bonding) is an attractive interaction between a hydrogen atom (H) covalently bonded to an electronegative donor atom (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a lone pair of electrons – the hydrogen bond acceptor (Ac). The general notation is Dn−H···Ac, where the solid line represents a polar covalent bond, and the dotted line indicates the hydrogen bond [6]. This interaction arises from a combination of electrostatics, charge transfer through orbital overlap, and dispersion forces, displaying partial covalent character that distinguishes it from purely electrostatic interactions [6].

The strength of hydrogen bonds varies considerably based on the donor-acceptor pair, geometry, and chemical environment, typically ranging from 1 to 40 kcal/mol – stronger than van der Waals interactions but generally weaker than covalent or ionic bonds [6]. Table 1 summarizes characteristic hydrogen bond strengths for biologically relevant pairs.

Table 1: Characteristic Hydrogen Bond Strengths in Various Systems

| Donor-Acceptor Pair | Example System | Bond Energy (kJ/mol) | Bond Energy (kcal/mol) | Strength Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F−H···:F− | HF⁻₂ ion | 161.5 | 38.6 | Very strong |

| O−H···:O | Water-water, Alcohol-alcohol | 21 | 5.0 | Strong |

| O−H···:N | Water-ammonia | 29 | 6.9 | Strong |

| N−H···:N | Ammonia-ammonia | 13 | 3.1 | Moderate |

| N−H···:O | Water-amide | 8 | 1.9 | Moderate |

| C−H···:O | Various molecular systems | <17 | <4.0 | Weak |

| C−H···:S | Organosulfur compounds | 4-13 (approx.) | 1-3 (approx.) | Weak [7] |

Structural Characteristics and Directionality

Hydrogen bonds exhibit distinct geometric preferences that contribute to their directionality in molecular self-assembly. The X−H distance is typically approximately 110 pm, whereas the H···Y distance ranges from 160 to 200 pm [6]. In water, the typical hydrogen bond length is 197 pm [6]. The ideal bond angle depends on the nature of the hydrogen bond donor, with linear (180°) D-H···A arrangements generally forming the strongest interactions, though significant deviation can occur with weaker donors or in constrained systems [6] [7].

The recent identification of C−H···S hydrogen bonding highlights the expanding understanding of non-traditional hydrogen bonds in biomimetic systems. These interactions, with strengths of 1-3 kcal/mol, meet the definition of proper hydrogen bonds and play important roles in molecular recognition, particularly with sulfur-containing biological molecules and reactive sulfur species [7].

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

X-ray Crystallography

Principle: Measures electron density distributions to determine atomic positions and identify D···A distances shorter than the sum of van der Waals radii as evidence of hydrogen bonding [6] [7].

Procedure:

- Grow high-quality single crystals of the target compound

- Collect X-ray diffraction data at appropriate temperature (typically 100-150 K for biomimetic compounds)

- Solve and refine the crystal structure

- Identify short D···A contacts (L2) and H···A distances (L1)

- Measure D-H···A (θ₁) and R-A···H (θ₂) angles

- Apply statistical analysis using databases (Cambridge Structural Database for small molecules, Protein Data Bank for biomacromolecules) to establish significance [7]

Key Parameters: L1 < sum of van der Waals radii; θ₁ typically 130-180°; θ₂ preferably approaching 180° for stronger bonds [7]

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Principle: Detects hydrogen bonding through downfield chemical shift changes of the involved proton in ¹H NMR spectra [6] [7].

Procedure:

- Prepare sample in appropriate deuterated solvent

- Acquire ¹H NMR spectrum at controlled temperature

- Compare chemical shifts (δH) with non-hydrogen-bonded references

- For C−H···S systems, chemical shift changes of up to 0.65 ppm have been observed for protons involved in hydrogen bonding [7]

- Perform titration experiments to measure association constants and binding energies

Application: Particularly valuable for detecting strong hydrogen bonds, such as the acidic proton in the enol tautomer of acetylacetone (δH = 15.5 ppm) [6]

Infrared Spectroscopy

Principle: Monitors X−H stretching frequency red shifts and band broadening due to hydrogen bond formation [6] [8].

Procedure:

- Acquire IR spectrum of compound in appropriate state (solution, solid, or gas phase)

- Identify X-H stretching region (e.g., O-H: 3600-3200 cm⁻¹, N-H: 3500-3300 cm⁻¹)

- Compare frequencies with non-bonded references

- Measure shift magnitude correlates with bond strength

- For advanced analysis, use variable-temperature IR to study hydrogen bond dynamics [6]

Application: The amide I mode of backbone carbonyls in α-helices shifts to lower frequencies when forming H-bonds with side-chain hydroxyl groups [6]

π-π Stacking Interactions

Fundamental Principles and Energetics

π-π stacking refers to reversible, noncovalent interactions between aromatic rings containing π-orbitals [9]. These interactions arise from the quadrupolar moment introduced by delocalized π-electrons, resulting in electrostatic interactions that compete with dispersion forces [9]. The benzene dimer represents the simplest prototype of π-π stacking, with binding energies of only 2-3 kcal/mol, explaining the challenge in studying these weak interactions [9].

Contrary to simplistic "sandwich" structures, parallel-displaced (staggered) configurations dominate π-π stacking, where aromatic rings are horizontally offset to maximize electrostatic attraction between positively charged hydrogen atoms and negatively charged π-clouds [9]. This configuration balances attractive van der Waals interactions with Pauli repulsion [9].

Structural Patterns and Biological Relevance

The strength of π-π stacking increases with the size of the conjugated system. Table 2 summarizes binding energies for representative polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, demonstrating this size-dependent enhancement.

Table 2: Binding Energies of π-π Stacking in Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

| Aromatic System | Number of π-electrons | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Preferred Configuration | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene dimer | 6 each | 2-3 | Parallel-displaced | DFT/MD [9] |

| Anthracene dimer | 14 each | 7.83 (SMD) / 8.30 (DFT) | Parallel-displaced | SMD/DFT [9] |

| Phenanthrene dimer | 14 each | 8.59 (SMD) / 9.08 (DFT) | Parallel-displaced | SMD/DFT [9] |

| Rhodamine 6G dimer | 12 each | 8.07 (SMD) / 8.55 (DFT) | Parallel-displaced | SMD/DFT [9] |

In biological systems, π-π stacking contributes to nucleic acid base pairing, protein structure stabilization, and molecular recognition events. These interactions are particularly important in drug design, where aromatic moieties in pharmaceutical compounds often engage in stacking interactions with biological targets.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) with Force Field Parameters

Principle: Utilizes molecular dynamics simulations with specially parameterized force fields to estimate binding energies of stacked aromatic dimers [9].

Procedure:

- Parameterize force field with specific atom types (e.g., CA for sp² carbons in aromatic rings) with unique ε and radius values [9]

- Perform MD simulations of free diffusion for aromatic molecules in explicit solvent (e.g., 100 ns time scale at 300 K)

- Monitor center of mass (COM) distance between molecules to identify spontaneous dimerization events

- For stable dimers, apply SMD to gradually separate molecules while measuring force

- Integrate force-distance curve to obtain binding energy

- Validate with quantum chemical calculations (e.g., DFT at ωB97X-D3/cc-pVQZ level) [9]

Advantages: Computationally efficient compared to full quantum mechanical calculations; good agreement with DFT results [9]

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

Principle: Quantum chemical approach that explicitly models electron distribution to calculate interaction energies.

Procedure:

- Select appropriate functional (e.g., ωB97X-D3) and basis set (e.g., cc-pVQZ) [9]

- Generate initial geometries of monomer and dimer structures

- Perform geometry optimization to locate energy minima

- Calculate binding energy as: Ebinding = Edimer - 2E_monomer

- Include correction for basis set superposition error (BSSE)

- Analyze interaction components using energy decomposition analysis

Application: Provides reference data for validating force-field methods; reveals detailed electronic structure contributions to stacking interactions [9]

Hydrophobic Effects

Fundamental Principles and Thermodynamics

The hydrophobic effect describes the tendency of nonpolar molecules or molecular surfaces to aggregate in aqueous environments, minimizing their contact with water [8] [10]. This phenomenon is involved in numerous chemical and biological processes, including molecular recognition, protein folding, membrane formation, and surfactant aggregation [8].

Contrary to early "hydrophobic bond" misconceptions, hydrocarbon-water attractions are actually stronger than hydrocarbon-hydrocarbon attractions, but weaker than water-water interactions [10]. The hydrophobic effect thus primarily stems from the strong self-attraction of water molecules through hydrogen bonding, which makes them thermodynamically prefer to interact with each other rather than with nonpolar solutes [10].

The thermodynamics of hydrophobic interactions depends on the size scale of the solute. For small solutes (<1 nm), the process is entropy-driven at room temperature, with minimal enthalpy changes. For larger hydrophobic surfaces, hydration involves significant enthalpic penalties due to broken water hydrogen bonds [8] [10].

Molecular Mechanism and Length-Scale Dependence

The molecular origin of hydrophobic effects lies in the structural competition between hydrogen bonding of interfacial versus bulk water [8]. When a hydrophobic solute is introduced to water, the interface mainly affects the structure of interfacial water (the topmost water layer). The hydration free energy depends on solute size, leading to different behaviors:

- Small hydrophobic solutes: Water molecules can reorganize around the solute while largely preserving their hydrogen-bond network, resulting in an entropy-driven process with minimal enthalpy changes.

- Large hydrophobic surfaces: Hydrogen bonds of water are broken at the solute surface, causing an enthalpic penalty that dominates the thermodynamics.

This size dependence leads to a crossover in hydration behavior at the nanometer length scale, with hydration free energy growing linearly with solute volume for small solutes but with surface area for large solutes [8].

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Hydration Free Energy Measurements

Principle: Determines the free energy change when transferring a solute from a nonpolar environment to water.

Procedure:

- Select a series of hydrophobic solutes with varying sizes and surface areas

- Measure partition coefficients (log P) between water and a nonpolar solvent (e.g., octanol)

- Calculate hydration free energy using: ΔG_hyd = -RT ln P

- Analyze dependence on solute volume (small solutes) or surface area (large solutes)

- Alternatively, use computational approaches to derive hydration free energy from structural studies of water and air-water interfaces [8]

Application: Reveals the crossover from entropy-driven to enthalpy-driven hydrophobic effects with increasing solute size [8]

Neutron Scattering with Contrast Variation

Principle: Probes water structure around hydrophobic groups in aqueous solutions.

Procedure:

- Prepare aqueous solutions containing hydrophobic solutes (e.g., tetramethylammonium chloride, methane)

- Use neutron scattering with isotopic substitution (H/D) to highlight different components

- Measure scattering patterns at multiple concentrations

- Analyze water structure through radial distribution functions

- Compare with bulk water structure to identify ordering or disordering effects

Application: Studies do not generally support increased tetrahedral order around small hydrophobic groups, contrary to the "iceberg" model [8]

Synergistic Integration in Biomimetic Self-Assembly

Cooperative Interaction Networks

In biological and biomimetic systems, hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and hydrophobic effects rarely operate in isolation. Instead, they form cooperative networks that enable sophisticated self-assembly with precise structural control and dynamic responsiveness. For instance, DNA base pairing combines hydrogen bonding with π-π stacking of nucleobases, while protein folding integrates hydrophobic clustering with specific hydrogen bonding patterns.

The hierarchical self-assembly observed in natural systems emerges from the interplay of these interactions operating across multiple length scales. By strategically designing molecular building blocks that leverage all three interactions, researchers can create biomimetic materials with programmable assembly pathways and functionalities.

Applications in Drug Delivery Systems

Self-assembled nanostructures for drug delivery represent a prime example where these interactions are harnessed in biomimetic materials. As illustrated in Figure 2, these systems utilize multiple non-covalent forces to create functional architectures for therapeutic applications.

Drug-based self-assembled nanostructures represent a promising platform where therapeutic agents spontaneously organize into well-defined structures stabilized through these non-covalent interactions [11]. These systems eliminate the need for additional nondrug excipients, making them efficient for targeted delivery [11]. Key advantages include improved drug bioavailability, enhanced solubility, greater stability, and targeted delivery to specific cell types and tissues, thereby minimizing off-target toxicity [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Non-Covalent Interactions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonding | Deuterated solvents (D₂O, CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | NMR spectroscopy for H-bond detection | Purity, water content, hydrogen-deuterium exchange |

| Cambridge Structural Database | Statistical analysis of geometric parameters | Subscription access, search expertise | |

| π-π Stacking | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (anthracene, phenanthrene) | Model systems for stacking studies | Purity, photostability, handling precautions |

| CHARMM 36 force field | Molecular dynamics parameterization | Proper atom typing (CA for aromatic carbons) | |

| Hydrophobic Effects | Tetramethylammonium chloride, methane derivatives | Model hydrophobic solutes for hydration studies | Purity, concentration range for neutron scattering |

| Partition coefficient standards (octanol-water) | Hydration free energy measurements | Standardized measurement protocols | |

| General Materials | Squalene conjugates, amphiphilic drugs | Self-assembly building blocks | Synthetic accessibility, characterization |

| Targeting ligands (folic acid, hyaluronic acid, oligopeptides) | Active targeting functionalization | Binding affinity, stability in circulation |

Hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and hydrophobic effects represent fundamental interaction mechanisms that collectively enable the sophisticated self-assembly processes observed in both biological systems and engineered biomimetic materials. The quantitative understanding of their strength, directionality, and context-dependence provides the foundation for rational design of functional nanomaterials with precise structural control. As characterization methodologies continue to advance, particularly in computational prediction and real-time monitoring of assembly processes, researchers are increasingly able to harness these interactions synergistically for applications in targeted drug delivery, biosensing, and adaptive materials. The continued refinement of our understanding of these key interaction mechanisms will undoubtedly yield next-generation biomimetic materials with enhanced complexity and functionality.

Biological templates represent a cornerstone of biomimetic materials research, leveraging evolutionary-optimized architectures from nature to synthesize advanced functional materials. This approach utilizes microbial and plant-derived structures as scaffolds or patterns to create porous materials with hierarchical structures that are often impossible to achieve through conventional synthesis methods. Framed within the broader context of biomimetic self-assembly, biological templating enables precise control over material architecture across multiple length scales, from nanometers to micrometers, facilitating the development of materials with enhanced properties for specialized applications in biomedicine, environmental remediation, and energy technologies [5].

The fundamental premise of biological temploring revolves around replicating and optimizing biological structures through techniques including biological templating, microbial templating, biomimetic mineralization, and self-assembly. These methods allow researchers to overcome the limitations of traditional materials synthesis, which often involves energy-intensive processes with significant waste generation and limited control over material properties [12]. In contrast, biological templating offers enhanced operational flexibility, improved mechanical properties of porous matrices, precise control over pore size distribution, optimal interporous connectivity, and reduced defect formation probability [5].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Biological Templating

Structural Principles from Nature

Biological templates exploit the unique structural organizations found in nature, where complex architectures have evolved to optimize specific functions. Plant-derived templates often feature hierarchical porous networks, such as the intricate vascular systems in leaves and stems, while microbial templates offer nanoscale surface features and metabolic activities that can direct material synthesis. These biological structures serve as scaffolds that can be replicated through various synthesis techniques, preserving their optimized architectures in inorganic or synthetic materials [5].

The self-assembly properties of biomimetic materials research are intrinsically linked to biological templating, as natural structures already employ sophisticated self-assembly principles. For instance, in plant cell walls, cellulose chains synthesized by enzymes crystallize in situ into nanofibers, which coassemble with cellulose-binding polysaccharides to form structures with remarkable mechanical properties [13]. Similarly, microbial surfaces provide precisely organized templates that can direct the assembly of molecules through electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and other non-covalent forces [5] [12].

Key Interactions in Bio-Templated Synthesis

The successful implementation of biological templates relies on fundamental interactions between the biological scaffold and the target material precursors:

- Electrostatic Interactions: Charged groups on biological surfaces (e.g., carboxyl groups in plant fibers, amine groups in microbial cell walls) facilitate the adsorption of precursor ions or nanoparticles [5] [14].

- Hydrogen Bonding: Hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amine groups on biological templates form hydrogen bonds with precursor molecules, directing their assembly and crystallization [15] [13].

- Biomineralization: Microorganisms can actively mediate mineral formation through metabolic processes that alter local pH or redox conditions, leading to template-directed precipitation [5] [12].

- Spatial Confinement: The physical dimensions of biological structures (pores, channels, surface features) confine material growth to specific geometries, replicating the template architecture [5] [13].

Plant-Derived Biological Templates

Plant-derived architectures offer a diverse array of structurally optimized templates for material synthesis. The preparation typically involves harvesting biological structures, processing them to preserve or modify their architecture, and then using them to direct material synthesis.

Table 1: Common Plant-Derived Templates and Their Applications

| Template Source | Processing Method | Resulting Material | Key Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotton fibers | Hydrothermal in situ growth | Hierarchical LDH/Al₂O₃ composites | Adsorption (90.27% BSA efficiency) | [5] |

| Lotus root | Freeze polymerization crosslinking | Multiscale porous polymers | CO₂ and aniline adsorption | [5] |

| Pomelo peel | Two-step leach calcination | Ru-TiO₂/PC composite photocatalyst | Visible-light photocatalysis | [5] |

| Canna leaves | Calcination in nitrogen | TiO₂-coated multilayer carbon | Enhanced photocatalytic performance | [5] |

| Epipremnum aureum leaves | Biomorphic synthesis | Porous Al₂O₃ with hierarchical microstructure | High-surface-area scaffold | [5] |

| Cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) | Evaporation-driven self-assembly | Cholesteric liquid crystalline films | Structural colors, sensors | [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Plant-Derived Templating

Hierarchical LDH/Al₂O₃ Composite Synthesis Using Cotton Templates

Objective: Fabricate fibrous crystalline alumina with hierarchical microporous 3D architecture for enhanced adsorption capabilities.

Materials:

- Cotton fibers (biological template)

- Aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) precursors

- LDH (Layered Double Hydroxides) precursors

- Hydrothermal reactor

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Clean cotton fibers thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol to remove impurities

- Prepare Al₂O₃ precursor solution (e.g., aluminum isopropoxide in ethanol)

- Immerse cotton fibers in Al₂O₃ precursor solution under vacuum to ensure complete infiltration

- Transfer to hydrothermal reactor and heat at 180°C for 12 hours

- Recover the Al₂O₃-coated fibers and calcine at 500°C for 2 hours to remove organic template

- Prepare LDH precursor solution (typically containing Mg²⁺ and Al³⁺ ions in specific ratio)

- Subject the Al₂O₃ fibers to secondary hydrothermal treatment with LDH precursors at 120°C for 6 hours

- Wash and dry the resulting LDH/Al₂O₃ composite

Key Parameters: Precursor concentration, hydrothermal temperature and duration, calcination conditions [5]

Biomimetic TiO₂-Coated Multilayer Carbon from Canna Leaves

Objective: Replicate multilayer leaf structure to create visible-light-active photocatalytic materials.

Materials:

- Fresh Canna leaves

- Titanium isopropoxide (TiO₂ precursor)

- Nitrogen gas supply

- Muffle furnace

Procedure:

- Wash Canna leaves thoroughly to remove surface contaminants

- Immerse leaves in titanium isopropoxide solution for controlled duration

- Slowly withdraw leaves to ensure uniform coating

- Air-dry coated leaves overnight

- Transfer to muffle furnace and calcine at 400-500°C under pure nitrogen atmosphere for 2 hours

- Gradually cool to room temperature under continued nitrogen flow

Key Parameters: Titanium precursor concentration, immersion time, withdrawal speed, calcination temperature [5]

Performance Metrics of Plant-Templated Materials

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Plant-Templated Materials

| Material System | Specific Surface Area (m²/g) | Key Performance Metric | Value | Application Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDH/Al₂O₃ composites | Not specified | BSA adsorption efficiency | 90.27% | High protein adsorption |

| Lotus root-templated polymers | High surface area | CO₂ and aniline adsorption | Significant enhancement | Rapid mass transport |

| Ru-TiO₂/PC photocatalyst | Large specific surface area | Visible-light absorption | Substantial capacity | Outstanding photocatalytic performance |

| TiO₂-coated carbon materials | High specific surface area | Photogenerated electron-hole separation | Improved separation | Enhanced organic degradation and H₂ generation |

| Al₂O₃ leaf-templated structure | High surface area | Structural replication | Faithful hierarchical reproduction | Platform for photocatalytic composites |

Microbial Biological Templates

Microbial Systems and Their Applications

Microorganisms provide versatile templates for material synthesis through their cellular structures and metabolic activities. Different classes of microorganisms offer distinct advantages based on their surface properties, size, and biological functions.

Table 3: Microbial Template Systems and Applications

| Microbial Template | Synthesis Approach | Resulting Material | Key Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urease-producing bacteria | Microbially induced carbonate precipitation | Heavy metal carbonates | Wastewater treatment (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ removal) | [5] |

| Yeast cells (S. cerevisiae) | Biomimetic mineralization with polyelectrolytes | Wavy-surfaced hollow spheres | Microcapsules with tunable permeability | [5] |

| Caustic alkali-pretreated yeast | Surfactant-free emulsion stabilization | Interconnected superporous adsorbents | Radioactive ion adsorption (Rb⁺, Cs⁺, Sr²⁺) | [5] |

| Magnetotactic bacteria | Biomineralization in magnetosomes | Magnetic nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄ or Fe₃S₄) | Magnetic materials, biomedical applications | [12] |

| Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria | Enzyme-induced phosphate precipitation | Heavy metal phosphates | Bioremediation of metal contaminants | [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Microbial Templating

Heavy Metal Removal via Microbially Induced Carbonate Precipitation

Objective: Synthesize innovative adsorbents for heavy metal removal from wastewater using urease-producing bacteria.

Materials:

- Urease-producing bacteria (e.g., Sporosarcina pasteurii)

- Urea broth medium

- Heavy metal solutions (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ at specified concentrations)

- Calcium chloride (CaCl₂)

- Centrifuge and incubation equipment

Procedure:

- Culture urease-producing bacteria in urea broth at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm) for 24-48 hours

- Harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 10 minutes

- Resuspend bacterial pellet in reaction solution containing urea (3g/L), CaCl₂ (2.5g/L), and heavy metal ions (concentration based on contamination level)

- Incubate reaction mixture at 30°C with mild shaking (50 rpm) for 24-72 hours

- Monitor pH increase due to urea hydrolysis (from ~7.0 to ~8.5)

- Collect precipitates by centrifugation and characterize for metal carbonate formation

Key Parameters: Bacterial cell density, urea concentration, metal ion concentration, incubation time [5] [12]

Yeast-Templated Porous Microcapsules via Biomimetic Mineralization

Objective: Fabricate porous microcapsules with distinctive wavy-surfaced hollow spheres using yeast cells as core templates.

Materials:

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker's yeast)

- Poly (diallyl dimethylammonium chloride) (PDDA)

- Polyacrylic acid (PAA)

- Precursor solutions for target material

- Muffle furnace for calcination

Procedure:

- Culture yeast cells in standard growth medium to mid-log phase

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and wash with deionized water

- Resuspend yeast cells in PDDA solution (1 mg/mL in 0.5 M NaCl) for 20 minutes with gentle agitation

- Centrifuge and wash to remove excess PDDA

- Resuspend in PAA solution (1 mg/mL in 0.5 M NaCl) for another 20 minutes

- Repeat polyelectrolyte layering as needed to achieve desired coating thickness

- Add material precursors for mineralization reaction

- Incubate for specified time to allow mineralization on template surface

- Recover composite material and calcine at 500°C to remove biological template

Key Parameters: Yeast cell concentration, polyelectrolyte concentration and molecular weight, mineralization time, calcination temperature [5]

Performance Metrics of Microbial-Templated Materials

Table 4: Quantitative Performance of Microbial-Templated Materials

| Material System | Template Organism | Key Performance Metric | Value | Application Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy metal carbonates | Urease-producing bacteria | Heavy metal adsorption | High efficiency | Effective Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ removal |

| Porous microcapsules | Yeast cells | Elastic modulus and hardness | Enhanced values | Superior impermeability |

| Radioactive ion adsorbents | Pretreated yeast | Adsorption capacity retention | ~99% after 5 cycles | Efficient Rb⁺, Cs⁺, Sr²⁺ removal |

| Magnetic nanoparticles | Magnetotactic bacteria | Magnetic properties | Controlled size and morphology | Biomedical applications |

| Phosphate precipitates | Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria | Heavy metal stabilization | Thermodynamic stability | Lower pH tolerance |

Advanced Characterization and Experimental Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of biological templating strategies requires specific reagents and materials optimized for interacting with biological systems while enabling precise material synthesis.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Biological Templating

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(diallyl dimethylammonium chloride) - PDDA | Cationic polyelectrolyte for surface modification | Yeast cell templating, layer-by-layer assembly | Molecular weight affects film thickness and uniformity |

| Polyacrylic acid - PAA | Anionic polyelectrolyte for multilayer assembly | Microbial surface functionalization | Concentration and pH critical for adsorption |

| Uridine 5'-diphosphate glucose - UDP-glucose | Enzyme substrate for cellulose synthesis | In vitro enzymatic synthesis of low-molecular-weight cellulose | Purity essential for controlled polymerization |

| Cellodextrin phosphorylase - CDP | Enzyme for cellulose oligomerization | Biomimetic hydrogel formation with polysaccharides | Activity assays required for consistency |

| Ionic liquids (e.g., CnECholBr) | Green solvents with antimicrobial properties | Surface-active agents, biofilm control | Biodegradability varies with alkyl chain length |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose - CMC | Cellulose-binding polysaccharide | Stiff hydrogel formation with LMW cellulose | Degree of substitution affects interaction with cellulose |

| S811 chiral dopant | Induces helical structures in liquid crystals | Biomimetic Bouligand structures in thin films | Concentration determines pitch length |

Diagram: Workflow for Biological Template-Mediated Material Synthesis

The following diagram illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for developing materials through biological temploring approaches, integrating both plant-derived and microbial strategies:

Diagram Title: Biological Template-Mediated Material Synthesis Workflow

Diagram: Self-Assembly Mechanisms in Biomimetic Materials

Understanding the self-assembly principles underlying biological temploring is essential for advancing biomimetic materials design. The following diagram illustrates key mechanisms and their relationships:

Diagram Title: Self-Assembly Mechanisms in Biomimetic Materials

Biological templates derived from microbial and plant sources represent a powerful paradigm for materials synthesis that aligns with the broader principles of biomimetic self-assembly. These approaches leverage evolutionary-optimized architectures to create functional materials with hierarchical structures, enhanced properties, and improved sustainability profiles compared to conventional synthesis methods.

The future of biological temploring will likely focus on several key areas: (1) developing hybrid approaches that combine multiple biological templates to create materials with synergistic properties, (2) advancing synthetic biology tools to engineer microbial templates with enhanced functionality and specificity, (3) scaling up production methods while maintaining structural fidelity, and (4) expanding the range of applications to include advanced drug delivery systems, tissue engineering scaffolds, and next-generation energy storage devices.

As the field progresses, integration of computational design with experimental implementation will enable more precise control over template-directed material synthesis. Machine learning approaches can help predict optimal template-material combinations and processing parameters, accelerating the development of novel biomimetic materials with tailored properties for specific applications. The continued exploration of biological templates promises to yield increasingly sophisticated materials that bridge the gap between biological complexity and engineering functionality.

Biomimetic mineralization represents a frontier in materials science, employing nature's principles to direct the synthesis and assembly of inorganic nanostructures. This whitepaper delineates the core mechanisms, methodologies, and applications of biologically inspired mineralization, framing it within the broader context of self-assembling biomimetic materials. Unlike traditional high-temperature synthetic routes, these processes occur under benign conditions, leveraging molecular recognition, non-covalent interactions, and organic templates to exert precise control over the morphology, hierarchy, and functionality of inorganic materials such as calcium phosphate, silica, and metal oxides. This technical guide provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and advanced characterization techniques essential for harnessing biomimetic mineralization in applications ranging from regenerative medicine to environmental technologies.

Biomimetic mineralization is an efficient bottom-up approach where biological macromolecules precisely control the assembly of inorganic materials into mineralized structures [5]. This paradigm shift from conventional fabrication draws inspiration from natural biomineralization processes, such as the formation of bone, teeth, and seashells, which exhibit remarkable mechanical properties and hierarchical organization [17]. The process is characterized by its environmentally benign nature, cost-effectiveness, and precise controllability, enabling the fabrication of porous nanomaterials with tunable morphology and dimensions [5].

The fundamental distinction between engineered and biological materials lies in their formation. Biological structures are grown through biologically controlled self-assembly according to a genetic recipe, allowing for functional adaptation and hierarchical structuring. In contrast, engineered materials are fabricated according to a fixed design from a wide palette of elements, often requiring extreme conditions [17]. Biomimetic mineralization bridges this gap by replicating the natural strategy of using organic matrices to direct inorganic crystallization at ambient temperatures, leading to structures with enhanced structural fidelity and functional performance.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Templates

The controlled assembly of inorganic nanostructures is governed by specific mechanisms and templates that guide nucleation and growth.

The Role of Organic Matrices and Interfaces

In natural systems, the organic matrix provides a critical biointerface that templates and directs the mineralization process. For instance, in tooth enamel remineralization, a complex of polyfunctional organic and polar amino acids is required to form an organic matrix similar to that of natural enamel. This matrix provides crystallization processes and determines the orientation and binding of inorganic subunits [18]. The formation of a mineralized layer with properties surpassing natural enamel is contingent upon the homogeneous crystallization and binding of individual nanocrystals into a single complex by this organic booster [18].

Template-Directed Synthesis

Biological Tissue Templates: Plant and animal-derived architectures offer a diverse array of structurally optimized templates. For example, using cotton fibers as biological templates allows for the fabrication of fibrous crystalline alumina with a hierarchical microporous 3D architecture. Similarly, Canna leaves have been used as both a substrate and carbon precursor to create biomimetic titanium dioxide-coated multilayer carbon materials, which possess a multilayer structure and a nanoporous-rich surface that enhances photocatalytic performance [5].

Microbial Template Technique: This approach utilizes bacterial and biological cell structures as scaffolds for constructing novel porous architectures through mineralization processes. Urease-producing bacteria can be used in microbially induced carbonate precipitation, synthesizing innovative adsorbents through the coordination of free heavy metal ions with carbonate ions. Yeast cells are also effective templates; their robust redox enzyme systems facilitate the secretion of acidic macromolecules that promote spontaneous mineralization, leading to porous microcapsules or superporous adsorbents [5].

Table 1: Common Templates in Biomimetic Mineralization and Their Applications

| Template Type | Specific Example | Resulting Material/Structure | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Booster | Polar amino acid complex | Nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite layer | Enamel remineralization [18] |

| Plant Tissue | Canna leaves | TiO₂-coated multilayer carbon | Photocatalysis [5] |

| Plant Tissue | Lotus root | Multiscale porous polymers | CO₂ and aniline adsorption [5] |

| Microbial | Urease-producing bacteria | Carbonate precipitates | Heavy metal adsorbent [5] |

| Microbial | Yeast cells | Wavy-surfaced hollow spheres | Microcapsules [5] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Controlled Assembly

This section provides detailed methodologies for key biomimetic mineralization experiments.

Protocol: Biomimetic Mineralization of Tooth Enamel

This protocol is adapted from studies demonstrating the formation of a biomimetic mineralizing layer on dental enamel using nanocrystalline carbonate-substituted calcium hydroxyapatite (ncHAp) and an amino acid booster [18].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Source: Use human teeth with sound enamel (ICDAS code 0), extracted for orthodontic reasons. Clean teeth of plaque and store in distilled water at +4 °C.

- Sectioning: Using a low-speed (120 rpm) water-cooled diamond blade, segment teeth into ~2 mm thick segments.

- Cleaning: Clean enamel segments in an ultrasonic bath (transmitter power ~25 W) in distilled water for 60 s to remove residual contamination.

2. Sample Pretreatment (Group-Specific): Divide segments into groups for different pretreatment conditions:

- Group N1: Healthy enamel standards (no treatment).

- Group N2: Control (no pretreatment, stored in distilled water).

- Group N3: Acid-etching. Etch enamel surface with 38% orthophosphoric acid (H₃PO₄) for 30 seconds. Wash with distilled water.

- Group N4: Alkaline pretreatment. Place each sample in an alkaline solution of Ca(OH)₂ (pH=12) for 30 s. Wash with distilled water.

- Group N5: Two-step pretreatment. First, place sample in Ca(OH)₂ solution for 30 s. Wash, then place in an amino acid booster for 30 s.

3. Mineralization Procedure:

- Prepare a solution of nanocrystalline carbonate-substituted hydroxyapatite (ncHAp), pH 8.5.

- Immerse pretreated samples (N2-N5) in the ncHAp solution.

- Perform mineralization for 24 hours at room temperature.

- Wash the enamel segments in distilled water and store at 4 °C until analysis.

4. Analysis and Validation:

- Use Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) to characterize the morphology and homogeneity of the mineralized layer.

- Employ X-ray Diffraction (XRD) and Raman spectromicroscopy to analyze the crystallographic and molecular structure of the deposited ncHAp.

- Perform nanoindentation to measure the nanohardness of the mineralized layer. A successful mineralization, particularly from the N5 protocol, can show a ~15% increase in nanohardness in the enamel rods area compared to healthy natural enamel [18].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental sequence for the enamel mineralization protocol, highlighting the critical branching points for different pretreatment methods:

Protocol: Chiral Self-Assembly of Inorganic Nanostructures

Chiral inorganic structures exhibit properties useful for medical applications like molecular probes and tumor therapy. One common synthesis strategy is chiral ligand-induced assembly [19].

1. Synthesis of Chiral Gold Nanorods (Au NRs):

- Method: Seed-mediated growth.

- Procedure: Perform the synthesis in the presence of L- or D-cysteine as chiral ligands. The cysteine enantiomers direct the asymmetric growth of the gold nanorods.

- Outcome: This yields discrete Au NRs with strong chiroptical responses (circular dichroism) in the visible and near-infrared region [19].

2. DNA Origami-Templated Chiral Assembly:

- Template Design: Create a two-dimensional DNA origami template with an 'X' pattern of DNA capturing strands (15 nt) on both sides.

- Functionalization: Functionalize Gold Nanorods (AuNRs) with DNA sequences complementary to those on the origami template.

- Assembly: Mix the components. The AuNRs position themselves on the origami via DNA hybridization, self-assembling into helical structures with the origami intercalated between neighboring rods [19].

Characterization and Performance Data

Rigorous characterization is vital to confirm the structure and properties of biomimetic minerals.

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques for Biomimetic Mineralized Materials

| Analytical Technique | Information Obtained | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) | High-resolution surface morphology, homogeneity of mineralized layer. | Visualizing the nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite layer on enamel [18]. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Surface topography, roughness, and mechanical properties at the nanoscale. | Mapping the surface of remineralized enamel and measuring local hardness [18]. |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystallographic phase, crystal size, and preferred orientation. | Confirming the formation of nanocrystalline carbonate-substituted hydroxyapatite [18]. |

| Raman Spectromicroscopy | Molecular bonding, chemical composition, and phase identification. | Studying the molecular structure of biointerfaces with high spatial resolution [18]. |

| Nanoindentation | Nanomechanical properties (hardness, elastic modulus). | Quantifying the ~15% increase in nanohardness of the mineralized enamel layer [18]. |

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Selected Biomimetic Porous Materials

| Material | Synthetic Method | Key Performance Metric | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alumina/LDH Composite [5] | Biological templating (cotton fibers) | 90.27% adsorption efficiency for bovine serum albumin. | Environmental remediation |

| Multiscale Porous Polymer [5] | Biological templating (lotus root) | High CO₂ and aniline adsorption capacity. | Gas capture & environmental |

| All-ceramic Silica Nanofiber Aerogel [5] | Bionic blind bristle structure | Ultralow thermal conductivity (0.0232–0.0643 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹, -50 to 800 °C). | Energy-efficient insulation |

| Ru-TiO₂/PC Composite [5] | Biological templating (pomelo peel) | Enhanced visible-light absorption and outstanding photocatalytic performance. | Photocatalysis & H₂ generation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting biomimetic mineralization experiments.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Biomimetic Mineralization Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biomimetic Mineralization | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Boosters (e.g., Asp, Pro, Cysteine) [18] [19] | Form an organic matrix; control crystallization, orientation, and binding of inorganic nanocrystals; induce chirality. | Specific polar amino acids are chosen to mimic the natural enamel matrix or to act as chiral ligands for metal assembly. |

| Nanocrystalline Carbonate-Substituted Hydroxyapatite (ncHAp) [18] | Primary inorganic building block for biomimetic bone and enamel repair. | Its physical and chemical properties are closest to natural apatite. Carbonate substitution is crucial for bioactivity. |

| Calcium Hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) [18] | Alkaline pretreatment agent; prepares the biotemplate surface for enhanced mineralization. | Can be synthesized from bird eggshells via annealing to create CaO, followed by hydration. |

| Chiral Ligands (e.g., L-/D-Cysteine, Aspartic Acid) [19] | Induce asymmetric geometry and chiroptical properties in inorganic nanoparticles and their assemblies. | The enantiomer used (L or D) dictates the handedness of the final chiral structure. |

| DNA Origami Templates [19] | Provide a programmable, high-precision scaffold for the site-specific assembly of inorganic nanoparticles into complex shapes (e.g., helices). | Allows for exquisite control over the 3D arrangement of metallic nanoparticles like gold. |

| Biological Templates (e.g., plant tissues, microbial cells) [5] | Provide a pre-structured, often hierarchical, scaffold that is replicated during synthesis to create porous materials. | Templates like cotton, lotus root, and yeast cells impart their unique microstructures to the final material. |

Biomimetic mineralization has matured from a field of serendipitous discovery to a discipline grounded in systematic engineering principles [17]. The controlled assembly of inorganic nanostructures using organic templates and bioinspired processes enables the creation of materials with unparalleled hierarchical organization and functionality. As detailed in this guide, the successful application of these principles—from enamel repair to the synthesis of chiral nanomaterials for medicine—hinges on a deep understanding of the structure-function relationships in natural materials and their meticulous translation into experimental protocols.

The future of biomimetic mineralization lies in enhancing the precision and scalability of these techniques. Emerging directions include the integration of 3D printing and self-assembly to create hierarchically ordered porous transition metal compounds [20], the development of autonomous, self-regulating systems for environmental remediation [20], and a deeper exploration of chiral inorganic materials for advanced medical therapies, including precise tumor treatment and the induction of tissue regeneration [19]. Overcoming the challenges of mass production, long-term stability, and cost-effectiveness will be key to the widespread commercial deployment of these sophisticated bio-inspired materials.

The controlled organization of nanoscale building blocks into functional architectures is a cornerstone of modern nanotechnology and biomimetic materials research. Two fundamental paradigms—molecular self-assembly and directed assembly—enable the construction of nanostructures with spatial order, structural hierarchy, and replicable function. Self-assembly exploits spontaneous molecular interactions to create ordered patterns, while directed assembly employs external guidance to engineer order with enhanced precision. This comprehensive analysis compares these strategies across mechanistic principles, material systems, experimental methodologies, and performance metrics, with specific emphasis on their applications in biomimetic material design for therapeutic development and tissue engineering. The insights presented herein aim to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge and practical protocols necessary to advance next-generation biomimetic systems.

In biological systems, molecular self-assembly is the dominant form of chemical organization, responsible for nearly every critical cellular process from genome replication to cytoskeletal formation [21]. Natural systems have evolved to capitalize on self-assembly, converting chemically simple building blocks into sophisticated materials and machinery fundamental to cellular function [22]. Biomimetic research seeks to emulate these natural processes by designing synthetic systems that replicate the structural and functional attributes of biological assemblies.

The fundamental distinction between self-assembly and directed assembly lies in the degree of external control imposed on the organization process. Self-assembly relies on spontaneous organization through non-covalent interactions—hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and van der Waals forces—without external intervention [23] [24]. This approach mimics how natural systems like the cytoskeleton form through reversible protein interactions [22]. In contrast, directed assembly introduces external guidance through fields, templates, or patterned surfaces to dictate the organization pathway and final architecture [23] [25]. This paradigm combines the advantages of bottom-up self-assembly with top-down spatial control, enabling more complex and functionally specific architectures.

This technical review provides a comparative analysis of these assembly strategies, with particular emphasis on their implementation in biomimetic materials for biomedical applications. We present structured experimental protocols, performance metrics across key criteria, and visualization of assembly mechanisms to facilitate research in this rapidly advancing field.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Mechanisms

Molecular Self-Assembly: Biomimetic Foundations

Molecular self-assembly operates through the spontaneous organization of components into stable, well-defined structures driven by equilibrium thermodynamics. The process is governed by the principle of free energy minimization, where components arrange to achieve the most thermodynamically favorable state [24]. Biological systems exemplify this approach through the folding of polypeptides into complex three-dimensional proteins, the formation of phospholipid bilayers, and the hierarchical assembly of amyloid fibrils [22] [24].

In engineered biomimetic systems, self-assembly typically employs peptides, proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and synthetic polymers designed with complementary interaction sites. A prominent example is the self-assembly of short peptide sequences like diphenylalanine (FF), which forms amyloid-like nanofibrils through a nucleation-dependent mechanism involving β-sheet formation [22]. These assemblies emerge from carefully designed molecular recognition events where building blocks interact through:

- Complementary shape and geometry

- Balanced attractive and repulsive forces

- Reversible interaction mechanisms

- Molecular mobility to explore configurations

The dynamic, reversible nature of non-covalent bonds in self-assembled systems confers self-healing properties and environmental responsiveness, making them particularly valuable for biomedical applications such as drug delivery and tissue engineering [24].

Directed Assembly: Engineering Spatial Control

Directed assembly introduces external guidance to steer the organization process toward desired configurations that may not correspond to thermodynamic minima. This approach combines the advantages of bottom-up self-assembly with elements of top-down control, enabling precise spatial patterning and alignment of nanoscale features [23] [25].

The two primary methodologies for directed assembly are:

Graphoepitaxy: Utilizes physical topographical templates (trenches, posts) fabricated via lithography to confine and guide assembly. The sidewalls of these templates impose structural constraints that direct the orientation of assembling blocks [25].

Chemoepitaxy: Employs chemically patterned surfaces with precisely controlled interfacial energies to direct nanoscale organization. Chemical patterns create alternating surface affinities that preferentially attract specific components of the assembling system [25].

Directed assembly is particularly valuable for semiconductor manufacturing and electronic device fabrication, where precise feature registration is essential. In biomedical contexts, it enables the creation of patterned biomimetic surfaces that control cell adhesion, alignment, and differentiation [26] [25].

Table 1: Fundamental Principles of Assembly Paradigms

| Characteristic | Molecular Self-Assembly | Directed Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Driving Force | Thermodynamic equilibrium (free energy minimization) | Combined thermodynamic and external guidance |

| Control Mechanism | Intrinsic molecular properties and interaction specificity | External fields, templates, or patterned surfaces |

| Process Reversibility | High (dynamic non-covalent interactions) | Variable (dependent on guidance mechanism) |

| Spatial Precision | Limited to molecular recognition capabilities | High (can achieve atomic-scale critical dimension uniformity) |

| Primary Interactions | Non-covalent (hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, electrostatic) | Combination of non-covalent and directed alignment forces |

| Inherent Error Correction | Yes (through reversible interactions) | Limited (dependent on guidance system flexibility) |

Visualization of Assembly Pathways and Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental pathways and mechanisms for both self-assembly and directed assembly approaches, highlighting key decision points and methodological distinctions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Biomimetic Peptide Self-Assembly for Nanofiber Formation

This protocol describes the formation of amyloid-like nanofibrils from short peptide sequences, a foundational methodology in biomimetic material assembly with applications in tissue engineering and drug delivery [22].

Materials Required:

- Diphenylalanine (FF) peptide or other self-assembling sequences (e.g., FFKLVFF)

- Organic solvent (methanol, hexafluoroisopropanol)

- Aqueous buffer solution (pH ~7.4)

- Ultrasonic bath

- Temperature-controlled incubator or water bath

- Atomic force microscopy (AFM) or transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for characterization

Procedure:

- Peptide Solution Preparation: Dissolve the peptide in organic solvent (e.g., methanol) at a concentration of 1-100 mg/mL to create a stock solution. Sonication for 10-30 minutes may be required for complete dissolution.

Initiation of Assembly: Dilute the peptide stock solution into aqueous buffer under vigorous stirring. Critical parameters include:

- Final peptide concentration: 0.1-5 mg/mL

- Buffer ionic strength: 10-100 mM

- pH: Specific to peptide sequence (typically 5-8)

Incubation and Assembly: Incubate the solution at controlled temperature (20-37°C) for 2-48 hours. Assembly progression can be monitored through turbidity measurements, thioflavin T fluorescence, or circular dichroism spectroscopy.

Structural Characterization:

- AFM Sample Preparation: Deposit 10-50 μL of assembly solution onto freshly cleaved mica, incubate for 1-5 minutes, rinse gently with deionized water, and air dry.

- TEM Sample Preparation: Apply 5-10 μL of assembly solution to carbon-coated grid, blot after 1 minute, negatively stain with 1% uranyl acetate if needed, and air dry.

Mechanical Property Assessment: For hydrogel formation, rheological measurements can determine storage (G') and loss (G") moduli using oscillatory rheometry at 0.1-10% strain and 0.1-10 rad/s frequency.

Technical Notes: Environmental conditions significantly influence assembly outcomes. Humidity [22] and oxygen levels [22] must be controlled for reproducibility. For Fmoc-protected peptides, gelation may occur immediately upon pH adjustment.

Protocol: Directed Assembly of Block Copolymers via Graphoepitaxy

This protocol details the graphoepitaxial directed assembly of polystyrene-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) (PS-b-PMMA) for nanoscale patterning, a widely adopted methodology in semiconductor manufacturing and functional surface engineering [25].

Materials Required:

- Block copolymer (e.g., PS-b-PMMA with appropriate molecular weight for target feature size)

- Neutral brush layer material (e.g., random copolymer of PS and PMMA)

- Appropriate solvent (toluene, propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate)

- Pre-patterned substrate with topographic features

- Thermal annealing oven or solvent vapor annealing chamber

- Reactive ion etching system

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation:

- Clean substrate (silicon wafer) with oxygen plasma or piranha solution

- Apply neutral brush layer by spin-coating (1-2% solution in toluene) at 2000-4000 rpm for 60 seconds

- Anneal at 150-250°C for 5-30 minutes to form brush layer

- Rinse with toluene to remove ungraf ted polymer

Guiding Pattern Fabrication:

- Use lithography (optical, EUV, or electron beam) to create topographic patterns (lines, trenches, holes)

- Pattern dimensions should be integer multiples of the natural periodicity (L0) of the BCP

Block Copolymer Deposition:

- Prepare 0.5-2.0% BCP solution in appropriate solvent

- Spin-coat onto patterned substrate at 1500-3000 rpm for 60 seconds to achieve desired film thickness

- Soft bake at 70-100°C for 1 minute to remove residual solvent

Annealing and Microphase Separation:

- Thermal Annealing: Process at 180-250°C for 5-60 minutes under nitrogen atmosphere

- Solvent Vapor Annealing: Expose to controlled solvent vapor (e.g., toluene) for 1-60 minutes in saturated environment

Selective Block Removal and Pattern Transfer:

- Expose to UV radiation (254 nm) for 5-20 minutes to degrade PMMA block

- Develop in acetic acid or reactive ion etch (RIE) with oxygen plasma to remove degraded PMMA

- Use resulting pattern as etch mask for underlying substrate transfer

Technical Notes: The Flory-Huggins parameter (χ) and degree of polymerization (N) determine the inherent domain spacing (L0). Successful directed assembly requires precise matching of guide pattern dimensions to integer multiples of L0. Defect densities can be minimized through optimized annealing conditions and surface chemistry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Assembly Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Biomimetic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Building Blocks | Diphenylalanine (FF), Fmoc-FF, FFKLVFF, Elastin-like peptides (ELPs) | Self-assemble into nanofibers, hydrogels, and tubular structures | Mimic extracellular matrix components; tissue engineering scaffolds [22] [26] |

| Block Copolymers | PS-b-PMMA, PLA-b-PEG, PEO-b-PPO-b-PEO (Pluronics) | Form nanostructured domains through microphase separation | Create patterned surfaces for cell guidance; drug delivery vehicles [25] |

| Surface Modification Agents | Silane coupling agents, thiols for gold surfaces, neutral brush layers | Modulate surface energy and chemical patterning for directed assembly | Control cell-biomaterial interactions; create bioadhesive patterns [26] [25] |

| Crosslinking Agents | Genipin, glutaraldehyde, EDAC/NHS, photoinitiators (Irgacure 2959) | Stabilize assembled structures and enhance mechanical properties | Mimic natural crosslinking in tissues; improve scaffold stability [26] |

| Characterization Standards | Thioflavin T, Congo red, fluorescently-labeled biomolecules | Detect and characterize assembly structures and morphology | Identify amyloid-like structures; track assembly kinetics [22] |

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

The selection between self-assembly and directed assembly strategies involves critical trade-offs across multiple performance dimensions. The following comparative analysis outlines these trade-offs to inform research and development decisions.

Table 3: Comparative Performance Metrics of Assembly Strategies

| Performance Criterion | Molecular Self-Assembly | Directed Assembly | Biomimetic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|