Bypassing the Lysosomal Trap: Strategies for Efficient Endosomal Escape in Nanoparticle Drug Delivery

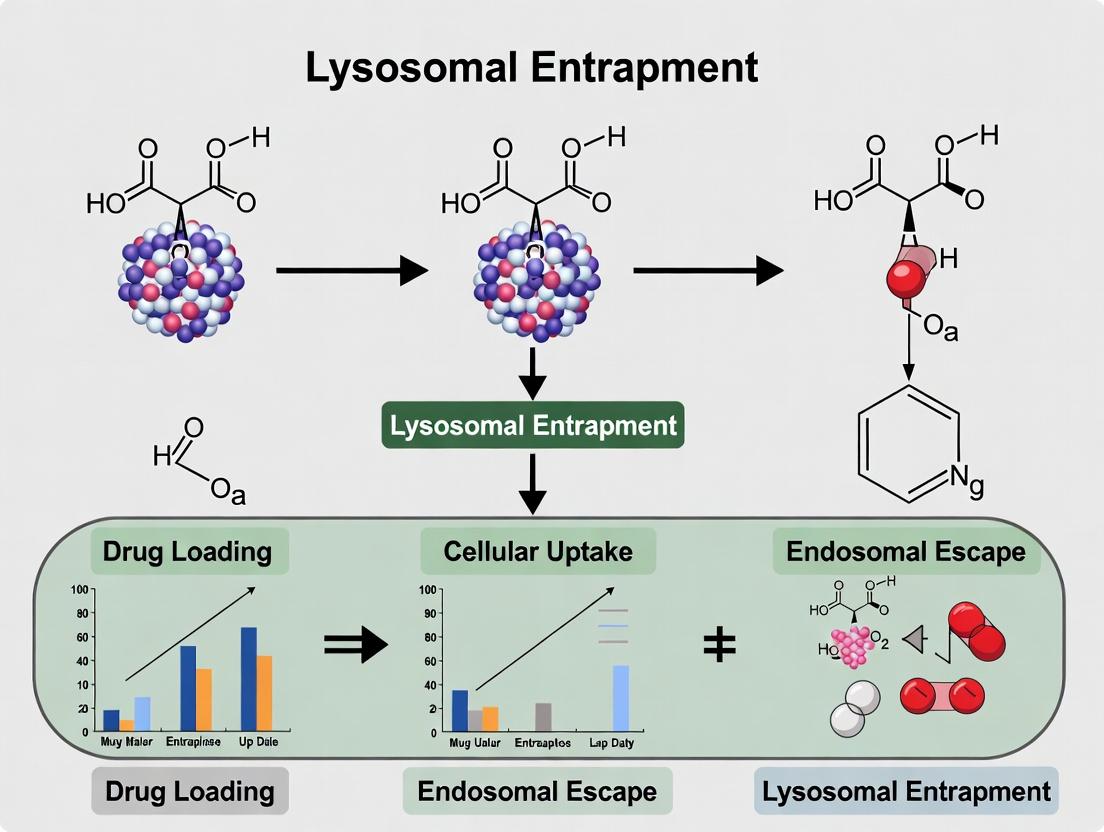

Lysosomal entrapment is a critical barrier limiting the therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery.

Bypassing the Lysosomal Trap: Strategies for Efficient Endosomal Escape in Nanoparticle Drug Delivery

Abstract

Lysosomal entrapment is a critical barrier limiting the therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of endocytosis and lysosomal degradation, reviews current and emerging strategies to engineer nanoparticles for efficient endosomal escape, discusses methods to evaluate and optimize escape efficiency, and compares the performance of different material classes and strategies. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to design next-generation nanocarriers that successfully bypass this key biological hurdle and achieve effective cytosolic drug delivery.

The Lysosomal Labyrinth: Understanding the Biology and Impact of Nanoparticle Entrapment

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Lysosomal Escape in Nanoparticle Drug Delivery

Welcome to the Nanodelivery Lysosomal Escape Technical Support Hub. This resource is designed to assist researchers in diagnosing and overcoming the critical barrier of lysosomal entrapment, which severely limits the cytosolic bioavailability of therapeutic cargo (e.g., nucleic acids, proteins, small molecules) delivered by nanoparticles.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our siRNA-loaded lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) show excellent cellular uptake but negligible gene knockdown. What's the primary suspect? A: Lysosomal entrapment is the most likely culprit. While uptake is efficient, the nanoparticles are being trafficked to the acidic lysosomal compartment where the siRNA is degraded before it can reach the cytosol and engage the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Check colocalization with lysotracker dyes.

Q2: How can I experimentally confirm if my nanoparticles are trapped in lysosomes? A: Perform a quantitative colocalization assay using confocal microscopy. Co-stain cells with a lysosomal marker (e.g., LysoTracker, LAMP1 antibody) and a fluorescent label on your nanoparticle. Colocalization coefficients (Pearson's > 0.7) typically indicate significant entrapment.

Q3: What are the most promising strategies to engineer "lysosome-escaping" nanoparticles? A: Current strategies focus on endosomal disruption mechanisms:

- Proton-Sponge Effect: Use polymers with high buffering capacity (e.g., PEI, PBAEs) to cause osmotic swelling and rupture.

- Fusogenic Lipids: Incorporate pH-sensitive, cone-shaped lipids (e.g., DOPE) that promote membrane fusion at low pH.

- Surface Charge Reversal: Design particles with charge that switches from anionic to cationic in lysosomes.

- Membrane-Disruptive Peptides: Conjugate peptides that undergo conformational change in acidic pH to puncture the lysosomal membrane.

Q4: We observe high cytotoxicity after modifying our particles for lysosomal escape. How can we mitigate this? A: Cytotoxicity often arises from non-specific membrane disruption. To mitigate:

- Titrate the "escape" functionality: Reduce the density of fusogenic lipids or peptides.

- Use biodegradable linkers: Ensure disruptive elements are cleaved after escape.

- Implement masking strategies: Use PEG shells or other stealth coatings that shed only in the acidic environment.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Cytosolic Delivery Efficiency

- Step 1: Verify Uptake. Quantify total cellular fluorescence (flow cytometry) to ensure the issue isn't simply poor internalization.

- Step 2: Map Intracellular Trafficking. Perform time-course colocalization studies with markers for early endosomes (EEA1), late endosomes (Rab7), and lysosomes (LAMP1/LysoTracker). See workflow below.

- Step 3: Test Escape Functionality. Use a reporter assay (e.g., Gal8-EGFP recruitment assay for endosome damage, or a cytosolic delivery fluorophore like Cytosolic Delivery Bright Green).

- Step 4: Iterate Design. Based on the trafficking map, choose an escape strategy timed to the dominant compartment of entrapment.

Issue: Inconsistent Escape Performance Across Cell Lines

- Cause: Variability in endocytic pathways, lysosomal pH, or protease activity between cell types.

- Solution:

- Characterize the endocytic mechanism in each line using pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., chlorpromazine for clathrin, amiloride for macropinocytosis).

- Measure lysosomal pH using rationetric pH probes.

- Adjust nanoparticle surface chemistry (ligands, charge) to steer entry into a more favorable pathway for your escape mechanism.

Table 1: Efficacy of Common Lysosomal Escape Strategies

| Strategy | Example Materials | Typical Escape Efficiency (% Cytosolic Release) | Common Cytotoxicity Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proton-Sponge Polymers | Polyethylenimine (PEI), Poly(amidoamine) | 15-35% | High, especially with high MW polymers |

| Fusogenic Lipids | DOPE, pH-sensitive cationic lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA) | 20-50% | Low to Moderate (highly structure-dependent) |

| Charge-Reversal NPs | Polymers with cis-aconityl or β-carboxylic amide linkages | 25-45% | Generally Low |

| Disruptive Peptides | GALA, HA2, melittin-derived peptides | 30-60% | High without controlled conjugation/masking |

Table Note: Efficiency is highly dependent on nanoparticle core, cell line, and cargo. Values represent typical ranges from recent literature.

Table 2: Standard Colocalization Analysis Outcomes & Interpretation

| Colocalization Result (with Lysotracker) | Pearson's Coefficient (Typical) | Mandel's Overlap (Typical) | Likely Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong Punctate Overlap | > 0.7 | > 0.8 | Significant Lysosomal Entrapment |

| Partial/Moderate Overlap | 0.4 - 0.7 | 0.5 - 0.8 | Mixed Trafficking; Some Escape |

| Low Overlap/Distinct Signals | < 0.4 | < 0.5 | Successful Avoidance or Escape |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantitative Confocal Microscopy for Lysosomal Colocalization

- Objective: Quantify the degree of nanoparticle colocalization with lysosomes.

- Materials: Cultured cells, fluorescent nanoparticles, LysoTracker Deep Red (100 nM), Hoechst 33342 (nuclear stain), confocal microscope, image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ/Fiji with Coloc2 or JACoP plugin).

- Method:

- Seed cells on glass-bottom dishes 24h prior.

- Incubate with nanoparticles for desired time (e.g., 4-6h).

- Replace medium with fresh medium containing LysoTracker and Hoechst. Incubate 30 min.

- Wash 3x with warm PBS. Image in live-cell compatible medium.

- Analysis: Use software to calculate Pearson's Correlation Coefficient (PCC) and Mandel's Overlap Coefficient (MOC) for the nanoparticle and LysoTracker channels on a per-cell basis (threshold applied). Analyze ≥ 30 cells per condition.

Protocol 2: Gal8-EGFP Recruitment Assay for Endolysosomal Damage

- Objective: Detect disruption of the endolysosomal membrane as an indicator of escape activity.

- Materials: Gal8-EGFP expressing cell line (or transiently transfected), nanoparticles, confocal microscope.

- Method:

- Seed Gal8-EGFP reporter cells.

- Treat cells with nanoparticles. Gal8 protein binds to exposed glycans upon endosome damage.

- At timepoints (e.g., 1, 2, 4h), image EGFP fluorescence. Untreated cells show diffuse cytosolic signal.

- Analysis: Quantify the number of bright Gal8-EGFP puncta per cell. An increase directly correlates with endolysosomal membrane disruption.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Nanoparticle Intracellular Trafficking and Escape Points

Diagram Title: Primary Lysosomal Escape Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying Lysosomal Entrapment

| Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| LysoTracker Dyes (e.g., Deep Red, Green) | Fluorescent Probe | Live-cell staining of acidic organelles (lysosomes). |

| LAMP1 Antibody | Immunofluorescence Marker | Specific immunostaining of lysosomal membrane protein. |

| Chloroquine / Bafilomycin A1 | Pharmacological Inhibitor | Raises lysosomal pH; used as control to inhibit acidification and block certain degradation pathways. |

| Gal8-EGFP Reporter Cell Line | Functional Assay System | Detects endolysosomal membrane damage via Galectin-8 recruitment. |

| PEI (Polyethylenimine), 25kDa | Proton-Sponge Control | A gold-standard polymer known for its buffering capacity; positive control for escape experiments. |

| DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) | Lipid | pH-sensitive, fusogenic lipid commonly blended with cationic lipids to promote escape. |

| Cytosolic Delivery Bright Green | Fluorescent Reporter Dye | Cell-permeant peptide conjugate that fluoresces only upon cleavage by cytosolic proteases, confirming cytosolic delivery. |

| Endocytic Pathway Inhibitors (Chlorpromazine, Amiloride, etc.) | Pharmacological Toolkit | To determine the primary uptake pathway, which influences subsequent trafficking. |

Technical Support Center

Welcome to the technical support center for investigating cellular uptake pathways. This resource is designed within the context of a research thesis aimed at overcoming lysosomal entrapment, a major bottleneck for nanoparticle (NP)-mediated drug delivery. The following guides address common experimental pitfalls.

Troubleshooting Guide: Uptake Pathway Inhibition & Validation

Issue 1: Inconclusive or Off-Target Effects from Pharmacological Inhibitors

- Problem: Your inhibitor experiment shows reduced fluorescence (e.g., from labeled NPs), but you suspect cytotoxicity or non-specific effects are causing the result.

- Solution: Always implement the following controls.

- Viability Check: Perform a concurrent cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, ATP-based) at the exact inhibitor concentration and exposure time used in your uptake experiment.

- Inhibitor Cocktail Toxicity: Test the combined toxicity when using multiple inhibitors.

- Positive Control Ligands: Use established positive controls for each pathway (see Table 1).

- Validation: Correlate with a second method (e.g., genetic knockdown/knockout).

Issue 2: Inconsistent Results in siRNA/Knockdown Experiments

- Problem: Uptake is not sufficiently inhibited after siRNA treatment against a key endocytic protein (e.g., CLTC for clathrin).

- Solution:

- Verify Knockdown Efficiency: Always measure protein knockdown via western blot from the same experiment used for uptake quantification. Do not rely on literature efficiency alone.

- Optimize Transfection: Use a fluorescently-labeled non-targeting siRNA to confirm >95% transfection efficiency in your cell line.

- Timing: Align the peak of protein knockdown (usually 48-72h post-transfection) with your uptake assay.

Issue 3: Distinguishing Macropinocytosis from Other Pathways

- Problem: It is challenging to confirm macropinocytic uptake definitively.

- Solution: Employ a multi-pronged validation strategy.

- Pharmacological: Use EIPA (5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride) at 50-100 µM.

- Morphological: Use dextran (70 kDa, TMR-labeled) as a co-tracker; its large size and lack of specific receptor targeting make it a canonical macropinocytosis probe.

- Biochemical: Test Na⁺/H⁺ exchanger dependence (EIPA's mechanism) and actin dependence (using Cytochalasin D).

Issue 4: Quantifying Co-localization for Lysosomal Entrapment

- Problem: High Pearson's Coefficient with lysosomal markers (e.g., LAMP1) confirms entrapment, but the value is skewed by a few bright pixels.

- Solution:

- Use Manders' Colocalization Coefficients (M1 & M2) in addition to Pearson's. These measure the fraction of NP fluorescence that overlaps with the lysosome marker, which is more biologically relevant for trafficking studies.

- Perform line profile analysis across vesicles in merged images to visually confirm signal overlap.

- Use lysosomotropic agents (e.g., Bafilomycin A1) as a functional control. If NP signal increases (due to prevented lysosomal degradation), it confirms lysosomal localization.

FAQs: Addressing Specific Experimental Challenges

Q1: Which combination of inhibitors is most effective for a comprehensive uptake mechanism screen? A: A standard initial screen should target the major pathways in parallel, with careful attention to solvent and toxicity controls (see Table 2).

Q2: How long should I pre-treat cells with inhibitors before adding nanoparticles? A: Pre-treatment times are inhibitor-specific and critical for efficacy.

- Chlorpromazine: 30 min - 1 hr.

- Dynasore: 30 min.

- Genistein / Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD): 30 min - 1 hr.

- EIPA: 15 - 30 min.

- Cytochalasin D / Latrunculin A: 15 - 30 min.

- Always use serum-free media during inhibitor pre-treatment and uptake assays to avoid interference.

Q3: My nanoparticles aggregate in physiological buffer, affecting uptake. How can I mitigate this? A:

- Characterize: First, measure hydrodynamic diameter and PDI by DLS in complete cell culture medium at 37°C over 24 hours.

- Stabilize: Use sterile filtration (0.22 µm) or sonication (water bath, 5-10 min) immediately before adding to cells.

- Additive: Include low-concentration (0.05-0.1% w/v) human serum albumin (HSA) or poloxamer (e.g., F68) in the NP dispersion buffer to sterically stabilize particles.

Q4: What is the best method to track nanoparticles from uptake to lysosomal delivery over time? A: Implement a pulse-chase experiment with live-cell imaging.

- Pulse: Incubate cells with fluorescent NPs for a short, defined period (e.g., 15-60 min).

- Chase: Replace medium with NP-free, pre-warmed medium.

- Image: Acquire time-lapse images at defined intervals (e.g., every 5-10 min for 2-4 hours) using a confocal microscope with environmental control.

- Label: Use a live-cell lysotracker dye (added during the chase phase according to manufacturer protocol) to visualize lysosome dynamics relative to NP cargo.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Pharmacological Inhibitors for Uptake Pathways

| Pathway | Target | Common Inhibitor | Typical Working Concentration | Key Consideration / Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis (CME) | Clathrin assembly | Chlorpromazine HCl | 5-20 µg/mL | Alters plasma membrane fluidity; check viability. |

| CME | Dynamin GTPase | Dynasore | 40-80 µM | Can inhibit mitochondrial dynamin; use limited exposure. |

| Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis | Tyrosine kinases | Genistein | 100-200 µM | Solubilize in DMSO; final [DMSO] < 0.5%. |

| Caveolae / Lipid Rafts | Cholesterol depletion | Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) | 2-10 mM | Drastically alters membrane properties; use short treatment (<1 hr). |

| Macropinocytosis | Na⁺/H⁺ exchanger | EIPA | 50-100 µM | Canonical macropinocytosis inhibitor; also affects other pH-dependent processes. |

| Actin-Dependent (All pathways) | Actin polymerization | Cytochalasin D | 1-5 µM | Broad-spectrum; disrupts most endocytic mechanisms. |

Table 2: Standardized Experimental Conditions for Initial Uptake Screening

| Parameter | Condition 1 (CME) | Condition 2 (Caveolae) | Condition 3 (Macropinocytosis) | Control Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | Dynasore (80 µM) | Genistein (200 µM) | EIPA (75 µM) | DMSO (0.5% v/v) |

| Pre-treatment Time | 30 min | 30 min | 20 min | 30 min |

| Serum during Treatment | Serum-free | Serum-free | Serum-free | Serum-free |

| Assay Temperature | 37°C & 4°C | 37°C | 37°C | 37°C |

| Positive Control Probe | Transferrin (Alexa Fluor 488) | Cholera Toxin B Subunit (AF555) | Dextran (70 kDa, TMR) | All probes |

| Mandatory Validation | Viability assay, 4°C uptake baseline | Cholesterol repletion control | Co-localization with dextran | Solvent vehicle control |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Uptake Pathway with Inhibitors & Flow Cytometry Objective: To quantify the contribution of a specific pathway to the cellular uptake of fluorescent nanoparticles. Materials: Adherent cells, fluorescent NPs, pharmacological inhibitors, flow cytometry buffer (PBS + 1% BSA + 0.1% NaN₃), trypsin/EDTA. Steps:

- Seed cells in a 24-well plate to reach 70-80% confluency at assay time.

- Prepare inhibitor solutions in pre-warmed, serum-free medium.

- Aspirate cell medium and add inhibitor/vehicle solutions. Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for the specified pre-treatment time.

- Add fluorescent NPs directly to the inhibitor-containing medium. Incubate for the desired uptake period (e.g., 2 hours).

- Stop Uptake & Wash: Place plate on ice. Aspirate medium and wash cells 3x with ice-cold PBS.

- Harvest: Add trypsin/EDTA (without phenol red) to detach cells. Neutralize with complete medium. Transfer cells to FACS tubes.

- Wash & Analyze: Pellet cells (300 x g, 5 min), resuspend in ice-cold flow cytometry buffer, and keep on ice. Analyze fluorescence intensity via flow cytometry (≥10,000 events per sample). Use untreated cells and cells at 4°C for baseline subtraction.

Protocol 2: Co-localization Analysis via Confocal Microscopy Objective: To visualize and quantify the localization of NPs with endocytic and lysosomal markers. Materials: Cells on glass-bottom dishes, fluorescent NPs, fluorescent markers (e.g., Transferrin-AF488, Dextran-TMR, LysoTracker Deep Red), fixation/permeabilization buffer, primary & fluorescent secondary antibodies (e.g., anti-LAMP1), mounting medium with DAPI. Steps:

- Pulse-Chase: Incubate cells with NPs in complete medium for the "pulse" duration (e.g., 30 min). Replace with NP-free medium for the "chase" period (e.g., 2, 4, 24 hours).

- Live-Cell Staining (Optional): For lysotracker, add dye to chase medium for final 30 min.

- Fix & Permeabilize: Wash with PBS, fix with 4% PFA for 15 min, wash, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min.

- Immunostaining: Block with 5% BSA for 1 hr. Incubate with primary antibody (e.g., anti-LAMP1, 1:200) overnight at 4°C. Wash, incubate with secondary antibody (e.g., AF647, 1:500) for 1 hr at RT. Wash.

- Image: Acquire z-stack images using a confocal microscope with sequential scanning to avoid bleed-through.

- Analyze: Use ImageJ/Fiji with coloc2 or JaCoP plugins to calculate Pearson's and Manders' coefficients from thresholded images.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Key Endocytic Pathways to Lysosome

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Uptake & Trafficking

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item / Reagent | Primary Function in Uptake Studies | Key Consideration for Lysosomal Entrapment Thesis |

|---|---|---|

| Dynasore | Dynamin inhibitor; blocks CME and caveolae scission. | Useful for determining if uptake is dynamin-dependent, a characteristic of many lysosome-destined pathways. |

| EIPA (Amiloride analog) | Inhibits Na⁺/H⁺ exchange; canonical macropinocytosis blocker. | Macropinocytosis often leads to lysosomal delivery; inhibiting it can test alternative, non-degradative routes. |

| LysoTracker Dyes (e.g., Deep Red) | Live-cell, acidotropic probes for labeling acidic organelles (lysosomes). | Critical for live-cell co-localization studies to track NP arrival in lysosomes in real time. |

| LAMP1 Antibody | Gold-standard marker for lysosomal membrane via immunofluorescence. | Used for fixed-cell confirmation of lysosomal co-localization with high specificity. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor; neutralizes lysosomal pH and blocks degradation. | Functional assay: if NP signal increases after treatment, it confirms lysosomal localization and degradation. |

| Chloroquine | Lysosomotropic agent that raises lysosomal pH. | Used to study "lysosomal escape"; if NP efficacy (e.g., drug action) increases, it suggests entrapment is limiting. |

| Fluorescent Dextran (70 kDa, TMR-labeled) | Fluid-phase marker for macropinocytosis. | Serves as a positive control for lysosomal trafficking via bulk uptake. |

| Transferrin, Alexa Fluor Conjugate | Ligand for transferrin receptor; marker for CME. | Positive control for a well-characterized CME-to-lysosome pathway. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guide for Lysosomal Pathway & Nanoparticle Research

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My fluorescently tagged nanoparticles show strong co-localization with LAMP1/LAMP2 markers. Does this definitively prove lysosomal entrapment and failure of escape?

A: Not definitively. Co-localization with late endosomal/lysosomal markers indicates localization to the acidic compartment, but it does not distinguish between active lysosomal degradation and temporary residence in a late endosome. To confirm entrapment and degradation, you must perform a functional assay:

- Protocol: Lysosomal Degradation Assay using DQ-BSA. Co-incubate cells with your nanoparticles and DQ-Red BSA (10 µg/mL). This substrate fluoresces only upon proteolytic cleavage. High red fluorescence in the same vesicles as your nanoparticles confirms an active, degradative lysosomal environment.

Q2: I am designing nanoparticles to promote endosomal escape. How can I best quantify and compare escape efficiency between formulations in vitro?

A: A robust method is the Cytosolic Delivery Assay using β-lactamase.

- Protocol: Use cells expressing a cytosolic CCF4-AM substrate (e.g., GeneBLAzer technology). CCF4 is FRET-based and emits green light. If your nanoparticle successfully delivers cytosolic β-lactamase, the enzyme cleaves CCF4, disrupting FRET and shifting emission to blue. Quantify the blue/green fluorescence ratio via flow cytometry or high-content imaging. Higher ratios indicate greater endosomal escape efficiency.

Q3: My drug-loaded nanoparticles lose efficacy over time in cell culture, but the drug alone is stable. Is this due to lysosomal degradation?

A: Very likely. This is a classic symptom of lysosomal entrapment where the carrier degrades before releasing its cargo.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Measure Lysosomal pH: Use a pH-sensitive reporter (e.g., LysoSensor Yellow/Blue) to confirm vesicles are at pH 4.5-5.0.

- Test with Inhibitors: Pre-treat cells with Bafilomycin A1 (20 nM, 1 hour), a V-ATPase inhibitor that neutralizes lysosomal pH and inhibits degradation. If nanoparticle efficacy is restored, it confirms the loss was due to acidic degradation.

- Direct Drug Stability Test: Incubate the drug-loaded nanoparticle in simulated lysosomal fluid (pH 4.5, with cathepsin B) and measure drug recovery by HPLC over 24 hours.

Q4: What are the best positive and negative controls for studying endosomal escape mechanisms?

A:

- Positive Control for Escape: Polyethylenimine (PEI, 25kDa) or Lipofectamine LTX. These are known to facilitate the "proton sponge" effect and disrupt endosomes.

- Negative Control for Entrapment: Inert polystyrene nanoparticles (e.g., 100nm carboxylated PS beads) or nanoparticles coated with only PEG. These typically follow the full pathway to lysosomes without escape.

- Control Experiment: Treat cells with chloroquine (50 µM) or ammonium chloride (20 mM) for 1 hour prior to and during nanoparticle incubation. These lysosomotropic agents raise endo-lysosomal pH and can artificially enhance the escape of some formulations, serving as a benchmark.

Table 1: Key Milestones & Durations in the Endosomal-Lysosomal Pathway

| Compartment | Typical pH | Key Marker Proteins | Approximate Time from Uptake | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Endosome | 6.0 - 6.5 | EEA1, Rab5, Transferrin Receptor | 2 - 5 minutes | Sorting: recycle or degrade. |

| Late Endosome / MVBs | 5.0 - 6.0 | Rab7, CD63, LBPA | 10 - 20 minutes | Cargo processing, ILV formation. |

| Lysosome | 4.5 - 5.0 | LAMP1, LAMP2, Cathepsin D | >30 minutes | Macromolecular degradation. |

Table 2: Common Strategies to Overcome Lysosomal Entrapment & Their Efficacy

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Reported Increase in Cytosolic Delivery* (Range) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proton Sponge Effect (e.g., PEI) | Buffers low pH, causes osmotic swelling & rupture. | 2 - 8 fold | High cytotoxicity; limited to polycations. |

| Fusogenic Peptides (e.g., GALA, INF7) | pH-dependent conformational change, membrane disruption. | 3 - 10 fold | Can be immunogenic; stability issues. |

| Surface Charge Reversal | Coating shifts from anionic at pH 7.4 to cationic at low pH. | 2 - 5 fold | Complex synthesis; potential off-target interactions. |

| Photo/Ultrasound Disruption | External trigger creates physical pores in endosome. | 5 - 15 fold | Requires precise targeting; specialized equipment. |

| Chemical Endosomolytics (e.g., Chloroquine) | Raises lumenal pH, inhibits maturation, weakens membrane. | 2 - 6 fold | Non-specific; toxic at high doses. |

*Compared to non-enhancing controls, varies widely by cell type and readout.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Co-localization Analysis of Nanoparticles with Endo-Lysosomal Markers Objective: Quantify nanoparticle progression through the pathway. Materials: Fixed cells, primary antibodies (EEA1, Rab7, LAMP1), fluorescent secondary antibodies, DAPI, mounting medium. Steps:

- Incubate cells with nanoparticles for desired timepoints (e.g., 15min, 1h, 4h, 24h).

- Wash, fix with 4% PFA for 15 min, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100.

- Block with 5% BSA for 1 hour.

- Incubate with primary antibody (1:200 in 1% BSA) overnight at 4°C.

- Wash 3x, incubate with fluorescent secondary antibody (1:500) and DAPI for 1 hour.

- Image using a confocal microscope with consistent settings. Use ImageJ or similar software with a plugin (e.g., JaCoP) to calculate Manders' or Pearson's co-localization coefficients for ≥30 cells per group.

Protocol 2: Assessing Lysosomal Integrity Post-Nanoparticle Treatment Objective: Determine if nanoparticles cause lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP), a toxic side effect. Materials: LysoTracker Red DND-99, propidium iodide (PI) or Galectin-3-GFP plasmid. Steps:

- Plate cells 24h prior. Transfect with Galectin-3-GFP if using that method.

- Treat cells with nanoparticles at relevant concentrations.

- For LysoTracker/PI: 30 min before the endpoint, add LysoTracker Red (50 nM) and PI (1 µg/mL). Wash and image live. Diffuse PI staining in LysoTracker-positive cells indicates LMP.

- For Galectin-3: Image GFP puncta (intact lysosomes) vs. diffuse cytosolic GFP (LMP). Quantify the percentage of cells with Galectin-3 puncta.

Pathway and Workflow Diagrams

Title: Nanoparticle Trafficking and Escape Opportunities

Title: Experimental Workflow to Test Lysosomal Escape

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Lysosomal Entrapment & Escape

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| LysoTracker Dyes (e.g., Red DND-99) | Fluorescent weak bases that accumulate in acidic compartments. | Live-cell staining to label all acidic endosomes and lysosomes. |

| LAMP1 / LAMP2 Antibodies | Lysosome-Associated Membrane Proteins. | Immunofluorescence marker for late endosomes/lysosomes. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Specific inhibitor of V-type H+-ATPase (proton pump). | Neutralizes endo-lysosomal pH to inhibit maturation & degradation. |

| Chloroquine Diphosphate | Lysosomotropic agent that raises luminal pH. | Positive control for enhancing endosomal escape of certain agents. |

| DQ-BSA | Heavily labeled BSA that fluoresces upon proteolysis. | To specifically visualize and quantify active degradative lysosomes. |

| CCF4-AM / β-lactamase | FRET-based substrate for β-lactamase enzyme. | Quantitative reporter assay for cytosolic (endosomal escape) delivery. |

| Galectin-3-GFP | Cytosolic protein that binds exposed glycans on damaged vesicles. | Sensitive reporter for Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization (LMP). |

| Recombinant Cathepsin B | Key lysosomal protease. | In vitro testing of nanoparticle stability under degradative conditions. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Mitigating Lysosomal Entrapment

FAQ 1: How can I confirm that my nanoparticle drug delivery system is suffering from lysosomal entrapment?

- Answer: Lysosomal entrapment is a primary cause of reduced drug efficacy. To confirm, you can perform co-localization studies.

- Protocol: Incubate your nanoparticle formulation with target cells (e.g., HeLa, MCF-7) for a predetermined time (e.g., 4-24h). Fix, permeabilize, and stain with:

- Primary Antibody: Anti-LAMP1 (Lysosomal-Associated Membrane Protein 1) or use a fluorescent dye like LysoTracker.

- Fluorescent Nanoparticle/Drug Label: Ensure your nanoparticle or payload (e.g., doxorubicin) is tagged with a spectrally distinct fluorophore (e.g., Cy5, FITC).

- Analysis: Use confocal microscopy and calculate Pearson's or Manders' co-localization coefficients. A coefficient >0.7 indicates significant entrapment. Quantify fluorescence intensity of the drug in lysosomal vs. cytosolic regions.

- Protocol: Incubate your nanoparticle formulation with target cells (e.g., HeLa, MCF-7) for a predetermined time (e.g., 4-24h). Fix, permeabilize, and stain with:

FAQ 2: My therapeutic payload is a siRNA. How do I determine if it is being degraded in lysosomes?

- Answer: siRNA integrity post-cellular uptake can be assessed via gel electrophoresis.

- Protocol:

- Treat cells with siRNA-loaded nanoparticles.

- After incubation (e.g., 12-48h), lyse cells and isolate total RNA.

- Run the RNA on a non-denaturing agarose gel (e.g., 2-4%).

- Stain with an RNA-specific dye (e.g., SYBR Gold).

- Expected Result: If siRNA is degraded, you will observe a smeared band or complete loss of the distinct siRNA band compared to the pristine control. Intact siRNA will show a clear, sharp band.

- Protocol:

FAQ 3: What experimental evidence can demonstrate drug inactivation due to the acidic lysosomal pH?

- Answer: Perform an in vitro drug stability assay mimicking lysosomal conditions.

- Protocol:

- Prepare a buffer simulating lysosomal pH (pH 4.5-5.0) and cytosolic pH (pH 7.4).

- Incubate your free drug or drug-loaded nanoparticles in both buffers at 37°C.

- Sample at various time points (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24h).

- Analyze drug concentration and integrity using HPLC or LC-MS.

- Data Presentation: The data clearly shows faster degradation at acidic pH.

- Protocol:

Table 1: Simulated Drug Stability in Lysosomal vs. Cytosolic pH Conditions

| Drug/Compound | Buffer pH | Half-life (t1/2) | % Intact Drug at 24h | Analytical Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin | 7.4 | >48 h | 98% | HPLC-Fluorescence |

| Doxorubicin | 4.5 | 12.5 h | 35% | HPLC-Fluorescence |

| Camptothecin (lactone form) | 7.4 | 8.3 h | 15% | LC-MS |

| Camptothecin (lactone form) | 4.5 | 0.5 h | <1% | LC-MS |

| Model siRNA | 7.4 | >72 h | >95% | Gel Electrophoresis |

| Model siRNA | 4.5 with RNase A | <0.1 h | 0% | Gel Electrophoresis |

FAQ 4: How do I quantitatively measure the reduction in bioavailability caused by entrapment?

- Answer: Compare the cytotoxic or therapeutic potency of free drug vs. nanoparticle-encapsulated drug. A right-ward shift in IC50 indicates reduced bioavailability.

- Protocol: Perform a standard cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo).

- Treat cells with a dose range of free drug and an equivalent dose range of drug loaded in nanoparticles.

- Incubate for 48-72 hours.

- Measure cell viability and calculate IC50 values.

- Interpretation: The ratio of IC50(NP) / IC50(Free) is the "Potency Loss Factor," directly correlating to reduced bioavailability. A factor >1 indicates entrapment/sequestration.

- Protocol: Perform a standard cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo).

Table 2: Impact of Lysosomal Entrapment on Drug Bioavailability (Potency)

| Cell Line | Drug | IC50 (Free Drug, nM) | IC50 (NP-Delivered Drug, nM) | Potency Loss Factor (IC50 NP / IC50 Free) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 (Breast Cancer) | Doxorubicin | 125 nM | 850 nM | 6.8 |

| PC-3 (Prostate Cancer) | Paclitaxel | 8.5 nM | 102 nM | 12.0 |

| HeLa (Cervical Cancer) | siRNA (GFP Knockdown) | 20 nM (Lipo. Transfect.) | 150 nM | 7.5 |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Endosomal Escape Efficiency Title: Quantifying Nanoparticle Endosomal Escape via Fluorescence Quenching/Dequenching Assay. Methodology:

- Labeling: Load nanoparticles with a high concentration of a pH-sensitive fluorophore (e.g., Calcein, FITC-dextran) that is self-quenched.

- Cell Treatment: Incubate labeled nanoparticles with cells for 2-4 hours. Remove media and wash.

- Quenching Control: Add an external quencher (e.g., Trypan Blue 0.4%) to the medium. This quenches only extracellular and endosomal fluorescence (still accessible via the endosomal lumen), but not cytosolic fluorescence.

- Imaging & Analysis: Immediately image using a plate reader or microscope. Calculate the percentage of protected (cytosolic) fluorescence:

% Escape = (Fluorescence with Quencher / Fluorescence without Quencher) * 100.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| LysoTracker Dyes (e.g., Deep Red) | Cell-permeant fluorescent probes that accumulate in acidic organelles. Vital for live-cell imaging of lysosomes. |

| LAMP1 Antibody | Gold-standard marker for late endosomes/lysosomes for fixed-cell immunofluorescence co-localization studies. |

| Chloroquine / Bafilomycin A1 | Lysosomotropic agents that raise lysosomal pH. Used as positive controls to inhibit acidification and demonstrate pH-dependent drug inactivation. |

| pH-Sensitive Fluorophores (e.g., CypHer5E, pHrodo) | Dyes that increase fluorescence upon acidification. Useful for tracking nanoparticle uptake and endosomal localization. |

| PEGylated Phospholipids (e.g., DSPE-PEG2000) | Common coating material to create "stealth" nanoparticles, which can alter protein corona and downstream trafficking, potentially affecting entrapment. |

| Endosomolytic Polymers (e.g., PEI, PPAA) | Polymers with protonable groups that disrupt the endosomal membrane via the "proton sponge" effect or membrane destabilization, promoting escape. |

| SYBR Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain | Highly sensitive dye for visualizing intact vs. degraded siRNA or oligonucleotides in gel assays. |

Diagram: Lysosomal Entrapment Consequences Pathway

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Entrapment Analysis

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Lysosomal Entrapment

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our nanoparticles show poor endosomal escape despite optimizing size. What could be the issue? A: Size is critical, but surface charge is often the dominant factor for endosomal escape. Positively charged surfaces (cationic polymers like PEI) promote the "proton sponge" effect, leading to osmotic swelling and endosomal rupture. If your neutral or anionic nanoparticles are trapped, consider:

- Verify Surface Charge (Zeta Potential): Ensure your measurement pH matches the endosomal pH (~5.5). A charge switchable polymer may be needed.

- Check Material Composition: Incorporate cationic lipids (e.g., DOTAP) or pH-sensitive polymers (e.g., PBAE) into your formulation. See Protocol 1 for a standard zeta potential measurement.

Q2: How do I accurately determine if my nanoparticles are trapped in lysosomes versus other organelles? A: Co-localization studies using specific dyes are essential.

- Issue: Faint or non-specific staining.

- Solution:

- Use LysoTracker Deep Red for live-cell imaging of acidic organelles.

- Fix cells and immunostain for LAMP-1, a definitive lysosomal marker.

- Use analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to calculate Manders' or Pearson's co-localization coefficients. A coefficient >0.7 indicates significant lysosomal entrapment. Refer to Protocol 2 for the detailed workflow.

Q3: We are using PEGylated nanoparticles to avoid clearance, but our drug efficacy is still low. Could PEG cause entrapment? A: Yes. While PEG prolongs circulation, it can also create a steric barrier that inhibits nanoparticle interaction with the endosomal membrane, a step necessary for escape. This is known as the "PEG dilemma."

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Shorten PEG Chain Length: Reduce from 5kDa to 2kDa or 1kDa.

- Use Cleavable PEG: Incorporate PEG linked via pH-sensitive (e.g., vinyl ether) or enzyme-sensitive bonds that shed inside the endosome.

- Optimize PEG Density: A lower surface density (e.g., 10% vs. 50%) may improve escape.

Q4: Our in vitro results show excellent escape, but in vivo drug delivery fails. What factors should we re-evaluate? A: This discrepancy often arises from the protein corona.

- Problem: Serum proteins adsorb onto nanoparticles in vivo, dramatically altering their surface charge and identity.

- Solutions:

- Pre-incubate nanoparticles with 10-50% FBS for 1 hour before in vitro assays to simulate corona formation.

- Re-measure hydrodynamic size and zeta potential post-incubation. A shift towards negative charge is common and can promote lysosomal trafficking.

- Consider "corona engineering" by pre-coating with specific proteins (e.g., albumin) to steer fate.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) & Zeta Potential Measurement for Nanoparticle Characterization

- Objective: Determine hydrodynamic diameter (size) and surface charge (zeta potential) of nanoparticles.

- Materials: Purified nanoparticle suspension, suitable cuvette (disposable for size, folded capillary for zeta), DLS/Zeta potential analyzer.

- Method:

- Dilute nanoparticle sample in the same buffer used for dialysis/filtration (e.g., 1xPBS, 1mM KCl) to a concentration that yields an ideal scattering intensity.

- Filter the diluted sample through a 0.45 or 0.22 µm syringe filter into a clean vial.

- For size: Load into a disposable sizing cuvette, insert into instrument, and run measurement at 25°C with appropriate material refractive index settings. Perform minimum 3 runs.

- For zeta potential: Load into a folded capillary cell. Measure at 25°C, with a minimum of 12 runs. Set the measurement pH to 7.4 (physiological) and 5.5 (endosomal) for comparison.

- Data Analysis: Report Z-Average size (d.nm) and PDI for polydispersity. Report zeta potential as mean ± standard deviation (mV).

Protocol 2: Confocal Microscopy for Lysosomal Co-localization Analysis

- Objective: Quantify the degree of nanoparticle co-localization with lysosomes.

- Materials: Cells grown on glass-bottom dishes, nanoparticle sample, LysoTracker Deep Red, Hoechst 33342, paraformaldehyde (4%), anti-LAMP1 primary antibody, fluorescent secondary antibody, blocking buffer (5% BSA in PBS), confocal microscope.

- Method:

- Treat cells with nanoparticles for desired time (e.g., 4-6 hours).

- Live-cell staining: Incubate with LysoTracker Deep Red (50-75 nM) and Hoechst 33342 (5 µg/mL) for 30 min at 37°C.

- OR Fix and immunostain: Wash cells, fix with 4% PFA for 15 min, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100, block for 1 hour. Incubate with anti-LAMP1 antibody overnight at 4°C, then with fluorescent secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temp. Counterstain nuclei with Hoechst.

- Image using a confocal microscope with appropriate laser lines and sequential scanning to avoid bleed-through.

- Export images and analyze using ImageJ with the "JACoP" plugin or similar. Calculate Manders' overlap coefficients (M1 and M2).

Table 1: Impact of Nanoparticle Properties on Lysosomal Trafficking and Escape

| Property | Optimal Range for Escape | Typical Trap-Prone Range | Key Mechanism & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic Size | 20 - 50 nm | >100 nm | Smaller size facilitates clathrin-mediated endocytosis and potential escape before late endosome maturation. Large particles often trafficked to lysosomes. |

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) | Slightly Positive (+5 to +15 mV) at pH 5.5 | Neutral or Negative (< -10 mV) at pH 5.5 | Cationic charge promotes proton sponge effect (buffering) and interaction with anionic endosomal membrane, leading to rupture. |

| Material Composition | pH-sensitive polymers (PBAE), cationic lipids (DOTAP), cell-penetrating peptides (TAT). | Non-degradable polymers (PS), Dense PEG shells. | Functional materials respond to endosomal low pH or redox conditions, causing structural destabilization and release. Inert materials follow default lysosomal pathway. |

Table 2: Common Characterization Techniques & Target Metrics

| Technique | Measures | Target Metric for Escape | Notes for Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic diameter, PDI | Size: 20-100 nm, PDI < 0.2 | High PDI (>0.3) indicates aggregation, which severely compromises performance and uptake uniformity. |

| Zeta Potential Analyzer | Surface charge in solution | Shift towards positive charge at endosomal pH (5.5) | Always measure in relevant buffer. A highly positive charge (>+30 mV) may indicate cytotoxicity. |

| Confocal Microscopy | Subcellular localization | Low co-localization coefficient with LAMP-1/LysoTracker | Use quantitative analysis (Pearson's R). Qualitative images alone are insufficient. |

Visualizations

Title: Nanoparticle Intracellular Trafficking & Escape Pathways

Title: Systematic Workflow to Diagnose Lysosomal Entrapment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Entrapment Studies | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylenimine (PEI), branched | Model cationic polymer for "proton sponge" effect. Induces endosomal rupture. | High molecular weight PEI (25kDa) is effective but cytotoxic. Use low MW or conjugate for delivery. |

| DOTAP (Cationic Lipid) | Component of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to impart positive charge, facilitating escape. | Often used with helper lipids (DOPE) to promote membrane fusion/destabilization. |

| LysoTracker Dyes | Fluorescent probes that accumulate in acidic organelles (late endosomes/lysosomes). | Use Deep Red for better photostability and to avoid overlap with common GFP/FITC channels. |

| LAMP-1 Antibody | Gold-standard marker for immunostaining of lysosomal membranes. | Provides definitive identification vs. early/late endosomes. Essential for quantitative co-localization. |

| Poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) | Biodegradable, FDA-approved polymer for NPs. Hydrolyzes in aqueous environments. | Inherently follows endolysosomal pathway. Requires surface functionalization (peptides, cations) for escape. |

| pH-sensitive polymer (e.g., PBAE) | Polymer that undergoes structural change or degradation at low endosomal pH. | Enables controlled, pH-triggered disassembly and content release. Library screening optimizes efficiency. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor that neutralizes endolysosomal pH. | Control experiment: If NP escape is inhibited by Bafilomycin, it confirms a pH-dependent escape mechanism. |

Engineered Escape: Proven and Novel Strategies for Lysosomal Bypass

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: In my transfection experiment using PEI/DNA polyplexes, I observe high cytotoxicity but low transfection efficiency. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

A: This is a common issue often related to an excessive polymer-to-DNA ratio (N/P ratio) or high molecular weight PEI. The high positive charge density can disrupt cell membranes excessively.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Optimize the N/P Ratio: Systematically test a range of N/P ratios (e.g., 5:1 to 15:1). Use the table below as a starting guide.

- Consider Polymer Form: Switch to lower molecular weight PEI (e.g., 10 kDa instead of 25 kDa) or use linear PEI instead of branched, as they are often less cytotoxic.

- Implement a Post-Transfection Media Change: Replace the transfection media with fresh growth media 4-6 hours after adding polyplexes to limit prolonged exposure.

- Verify pH of Buffers: Ensure the pH of your polyplex formation buffer (often HEPES or saline) is correct. Deviations can affect polyplex size and stability.

Q2: How do I accurately measure and control the N/P ratio for PEI polyplex formation?

A: The N/P ratio is the molar ratio of polymer nitrogen (N) to DNA phosphate (P). Accurate calculation is crucial.

- Protocol: Calculating and Preparing PEI/DNA Polyplexes at a Specific N/P Ratio

- Determine the concentration of DNA in µg/µL and its base pair length. The average molecular weight per base pair is ~660 g/mol.

- Calculate the micromoles of phosphate (P) in your DNA aliquot: µmol P = (mass of DNA in µg) / (330 µg/µmol). The constant 330 comes from the average molecular weight of a nucleotide phosphate (330 g/mol).

- For PEI, determine its nitrogen content. Branched PEI (e.g., Sigma 408727) has a nitrogen concentration of ~23 mmol/g for the 25 kDa form.

- Calculate the required mass of PEI solution: Volume PEI (µL) = (µmol P * N/P ratio) / (PEI Nitrogen Concentration in mmol/g * PEI solution concentration in g/L).

- Formation Protocol: Dilute the calculated amount of DNA in an appropriate volume of opti-MEM or serum-free buffer (e.g., 150 mM NaCl). In a separate tube, dilute the calculated amount of PEI in the same volume of the same buffer. Add the PEI solution dropwise to the DNA solution while vortexing. Incubate at room temperature for 15-30 minutes before use.

Q3: My polyplexes appear to aggregate or precipitate. How can I improve colloidal stability?

A: Aggregation is typically due to insufficient electrostatic stabilization, often in media with high salt or serum content.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Form Polyplexes in Low-Ionic-Strength Buffers: Use deionized water or 5% glucose instead of saline for initial formation. Perform a buffer exchange post-formation if needed.

- Introduce Steric Stabilization: Conjugate polyethylene glycol (PEG) to a portion of the PEI (PEGylation). This creates a hydrophilic shell that prevents aggregation and protein opsonization.

- Characterize Size and Zeta Potential: Use dynamic light scattering (DLS) to monitor polyplex hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential. Stable polyplexes should have a positive zeta potential (+10 to +30 mV) and a consistent, sub-200 nm size in their delivery buffer.

Q4: How can I experimentally confirm the "Proton Sponge Effect" is functioning in my system?

A: Direct confirmation requires measuring lysosomal pH buffering and rupture. Here is a key experiment.

- Protocol: Lysosomal pH Buffering Capacity Assay using Acridine Orange

- Plate cells (e.g., HeLa) in a 24-well plate.

- Treat cells with PEI polyplexes (without cargo) or chloroquine (positive control) in serum-free media. Untreated cells serve as a negative control.

- After 2-4 hours, incubate cells with 5 µg/mL Acridine Orange (AO) in complete media for 15 minutes.

- Wash cells gently with PBS. Immediately image using fluorescence microscopy.

- Expected Outcome: In control cells, AO accumulates in acidic lysosomes and emits intense red fluorescence. Cells where PEI buffers the lysosome will show a decrease in red fluorescence and an increase in diffuse green cytoplasmic fluorescence, indicating lysosomal permeabilization and AO release.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Influence of PEI Properties on Transfection and Cytotoxicity

| PEI Type (Molecular Weight) | Typical Optimal N/P Ratio | Transfection Efficiency | Relative Cytotoxicity | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branched PEI (25 kDa) | 8:1 - 10:1 | High | High | Standard for in vitro work; requires optimization. |

| Linear PEI (25 kDa) | 5:1 - 8:1 | High | Moderate | Often more efficient and less toxic than branched. |

| Branched PEI (10 kDa) | 10:1 - 15:1 | Moderate | Low | Useful for sensitive cell lines; may require higher N/P. |

| PEI-PEG Conjugate | Varies by PEG% | Moderate-High | Low | Improved stability and reduced toxicity for in vivo. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Polyplex Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Transfection Efficiency | Polyplexes too large, unstable, or not endocytosed. | Form polyplexes in low-ionic buffer; check size via DLS; add a targeting ligand. |

| High Cytotoxicity | Excessive positive charge, high MW polymer. | Lower N/P ratio; use lower MW PEI; change media after 4-6h. |

| Polyplex Aggregation | High salt during formation, lack of steric stabilization. | Use 5% glucose as formation buffer; consider PEGylation. |

| Inconsistent Results | Variability in polymer stock, inaccurate N/P calculation. | Aliquot and standardize PEI stock concentration; recalculate N/P fundamentals. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Formulating Stable PEI-siRNA Polyplexes for Gene Silencing

- Materials: Linear PEI (MW 40,000), siRNA (target and scramble control), Nuclease-Free Water, 5% Glucose solution, Opti-MEM.

- Preparation: Dilute 3 µg of siRNA in 50 µL of 5% glucose (Tube A). Dilute the required amount of PEI (for N/P ratio of 6) in 50 µL of 5% glucose (Tube B).

- Complexation: Rapidly mix the contents of Tube B into Tube A by pipetting. Vortex immediately for 10 seconds.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes to form stable polyplexes.

- Delivery: Add the 100 µL polyplex solution dropwise to cells in 1 mL of Opti-MEM. Incubate for 4-6 hours before replacing with complete growth media.

- Analysis: Assess gene knockdown via qPCR or Western blot 48-72 hours post-transfection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Branched Polyethylenimine (PEI), 25 kDa | The classic "proton sponge" polymer. High charge density facilitates complexation and endosomal buffering/rupture. |

| Linear Polyethylenimine (PEI), 40 kDa | Often shows higher transfection efficiency and lower cytotoxicity than branched PEI in many cell lines. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-PEI Conjugates | PEG chains grafted onto PEI improve solubility, reduce non-specific interactions, and enhance in vivo circulation time. |

| Chloroquine Diphosphate | Small molecule lysosomotropic agent used as a positive control for endosomal disruption. |

| Acridine Orange (AO) | Metachromatic dye used to visualize lysosomal integrity and pH; accumulation in acidic compartments shifts fluorescence from green to red. |

| LysoTracker Dyes | Fluorescent probes (e.g., LysoTracker Red) that specifically accumulate in acidic organelles, useful for imaging lysosomes. |

| HEPES-Buffered Saline | Common isotonic buffer for polyplex formation, maintains stable pH during complexation. |

| 5% Glucose Solution | Low-ionic-strength vehicle for polyplex formation, helps prevent aggregation during complex assembly. |

Mechanism & Workflow Visualizations

Mechanism of the Proton Sponge Effect for Endosomal Escape

Workflow for Optimizing PEI-Based Transfection Experiments

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My GALA or INF7 peptide is not inducing efficient endosomal/lysosomal escape. What could be wrong? A: Inefficient escape is common. First, verify the peptide-to-nanoparticle ratio (often 20-50 peptides per particle is optimal). Check the pH of the buffering system; these peptides require a precise pH drop (typically to ~pH 5.5-6.0) to undergo the conformational change to an amphipathic α-helix. Ensure your endocytic trafficking is not altered. Run a control using a fluorophore-quencher assay (e.g., Dio/DPX) to confirm membrane disruption activity independently of your cargo.

Q2: My photosensitizer (e.g., Verteporfin, Rose Bengal) mediated photochemical internalization (PCI) is causing excessive cytotoxicity. A: This indicates off-target membrane damage. Optimize three key parameters, which should be titrated in a matrix:

- Photosensitizer Concentration: Start with a low nM range (e.g., 1-50 nM).

- Light Dose (J/cm²): Use low fluence rates (e.g., 0.5-2 J/cm²).

- Incubation-to-Irradiation Interval: This is critical for lysosomal localization. Typically, a 4-18 hour incubation allows for endo-lysosomal accumulation. Perform a time-course experiment to find the window where lysosomal localization is maximal but photosensitizer redistribution to other membranes is minimal.

Q3: The endosomolytic polymer (e.g., PEI, PBAE) I am using is aggregating with my nanoparticle formulation. A: Polycationic polymers can cause non-specific aggregation. Consider:

- Order of Addition: Add the polymer to the pre-formed nanoparticles last, with gentle vortexing.

- Buffer Ionic Strength: Use a low-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., 10 mM HEPES) during formulation to minimize salt-bridge induced aggregation.

- Alternative Chemistry: Switch to a charge-shifting or pH-responsive polymer that is neutral or anionic at physiological pH (e.g., PMPC-PDPA) and only becomes cationic in the endosome, reducing serum interaction and aggregation.

Q4: How do I quantitatively compare the endosomal escape efficiency of different agents? A: Use a standardized, quantitative assay. The "Split Luciferase Endosomal Escape Assay" is highly recommended. See the detailed protocol below.

Q5: My controls suggest significant lysosomal entrapment despite using a disruption agent. What are the next steps? A: This is the core challenge. You may need a combinatorial approach.

- Co-formulation: Covalently conjugate or physically co-encapsulate a peptide (e.g., GALA) with a photosensitizer for a light-triggered, spatially precise double-disruption mechanism.

- Sequential Activation: Use a polymer that disrupts at early endosome pH (~6.5) followed by a peptide activated at late endosome/lysosome pH (~5.0-5.5).

- Check Trafficking: Use lysosomal inhibitors (e.g., Bafilomycin A1) to confirm the escape is pH-dependent. If escape improves with inhibition, your agent may be degrading before activation.

Experimental Protocol: Split Luciferase Endosomal Escape Assay

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the cytosolic delivery efficiency of membrane disruption agents.

Principle: A large protein, Gaussian Luciferase (GLuc), is split into two inactive fragments. One fragment (the large fragment, GLuc(1)) is delivered inside nanoparticles. The other (the small complementing fragment, SNAP-GLuc(2)) is expressed in the cytoplasm of the target cells. Only when the nanoparticle contents (GLuc(1)) escape the endosome and enter the cytoplasm will the fragments complement and generate luminescent signal.

Materials:

- Stable cell line expressing cytoplasmic SNAP-GLuc(2) (e.g., HeLa SNAP-GLuc(2)).

- Nanoparticles loaded with GLuc(1) fragment and your membrane disruption agent.

- Control nanoparticles without disruption agent.

- Lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100) for total uptake control.

- Native Glow Luciferase Assay Kit.

- Luminometer.

Procedure:

- Seed Cells: Plate cells in a 24-well plate at 70% confluency and incubate for 24h.

- Treat Cells: Add nanoparticle formulations (test and controls) in serum-free medium. Incubate for 4h at 37°C.

- Wash & Read Escape: Aspirate medium, wash cells 3x with PBS. Add 200 µL of pre-warmed, serum-containing medium to each well. Incubate for 1h to allow complementation. Transfer 50 µL of medium to a opaque-walled plate, add 50 µL luciferase assay reagent, and measure luminescence immediately (Escape Signal).

- Measure Total Uptake: For parallel wells, after 4h incubation, aspirate, wash 3x with PBS, and lyse cells with 200 µL lysis buffer. Measure luminescence of the lysate (Total Uptake Signal).

- Calculation: Normalize the Escape Signal of test samples to the Total Uptake Signal of the same sample and to the signal from control nanoparticles (set to 1% or 0% escape). This yields the Relative Escape Efficiency (%).

Table 1: Comparison of Membrane Disruption Agent Efficiencies & Parameters

| Agent Class | Example | Typical Working Concentration | Key Activation Trigger | Reported Escape Efficiency* | Major Cytotoxicity Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH-Sensitive Peptide | GALA | 10-100 µM (in formulation) | pH ~6.0 (Helix formation) | 15-30% (Split Luciferase) | Hemolysis at high conc. |

| pH-Sensitive Peptide | INF7 (HA2 derived) | 5-50 µM (in formulation) | pH ~5.5 (Fusion pore) | 20-40% (Split GFP) | Serum protein inhibition |

| Cationic Polymer | PEI (25 kDa) | N/P ratio 5-10 | Proton Sponge Effect (pH <6.5) | 10-25% (Gal8 assay) | High intrinsic toxicity |

| pH-Responsive Polymer | PMPC-PDPA | 10-50 mg/mL (polymer) | pH ~6.2 (Micelle de-stabilization) | 25-50% (Content release) | Low transfection efficiency alone |

| Photosensitizer | Verteporfin (PCI) | 10-100 nM + Light (1-5 J/cm²) | Light (~690 nm) & ROS | 30-60% (Cytosolic delivery) | Off-target photodamage |

*Efficiency values are highly dependent on cell type, assay, and formulation. Values represent ranges from recent literature (2023-2024).

Visualizations

DOT Diagram 1: Pathways for Lysosomal Escape of Nanoparticles

DOT Diagram 2: Split Luciferase Escape Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Membrane Disruption

| Reagent | Function & Rationale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor. Raises endo-lysosomal pH, used to confirm pH-dependent escape mechanisms. | Use at 50-100 nM. Highly toxic with prolonged (>4h) exposure. |

| Dextran, Alexa Fluor conjugates | Fluid-phase endocytosis markers and probes for endosomal integrity (quenched until release). | Use 10,000 MW for lysosomal trafficking. Useful for co-localization studies. |

| LysoTracker Dyes (e.g., Deep Red) | Stains acidic organelles. Visualize lysosomal mass and integrity post-treatment. | Signal lost upon membrane rupture/neutralization. Best for live-cell imaging. |

| Galectin-8 (Gal8) assay | Cytosolic galectin-8 binds exposed endosomal glycans upon damage, recruiting fluorescent tag (e.g., Gal8-mCherry). | Sensitive, qualitative/quantitative (imaging/flow) measure of endomembrane damage. |

| Dio/DPX Assay Kit | (Dio = lipophilic dye, DPX = quencher). Fluorescence dequenching upon membrane disruption. | In vitro lipid vesicle assay to test agent activity independent of cellular uptake. |

| CellTiter-Glo / LDH Kit | Measure viability (ATP) or membrane integrity (LDH release) to balance escape efficiency with cytotoxicity. | Critical for determining therapeutic index of any disruptor formulation. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My pH-responsive nanoparticle shows premature payload release at physiological pH (7.4). What could be the cause? A: Premature release often stems from linker instability or suboptimal material packing. First, verify the pKa of your cleavable bond (e.g., hydrazone, acetal, β-thiopropionate). Use the calibration table below to check buffer conditions. Ensure your nanoparticle purification protocol (e.g., dialysis, tangential flow filtration) thoroughly removes unencapsulated payload, which can confound release assays.

Q2: I observe insufficient payload release in the late endosome/lysosome pH range (4.5-5.5). How can I improve cleavage kinetics? A: This is a common challenge related to lysosomal entrapment. Consider switching to a linker with a higher hydrolysis rate at lower pH. For instance, replace a standard hydrazone with a cis-aconityl or a double-ester linker. Confirm that your material allows sufficient water penetration to the cleavable bonds. Perform a buffer capacity assay to ensure your nanoparticles effectively buffer the endosome and do not delay acidification.

Q3: How do I accurately measure and calibrate pH within in vitro cellular compartments to validate release? A: Use a combination of fluorescent pH sensors (e.g., LysoSensor, pHrodo dyes) and ratiometric measurements. Co-localize signal with lysosomal markers (e.g., LAMP1). The following protocol provides a standardized method.

Protocol 1: Calibration of Intracellular Compartment pH for Release Validation

- Seed cells in a glass-bottom dish.

- Incubate with pH-responsive nanoparticles (50 µg/mL) for 4 hours.

- Replace medium with fresh medium containing 100 nM LysoTracker Deep Red (90 min).

- Wash cells 3x with PBS.

- Image using confocal microscopy (ex/em for your payload and LysoTracker).

- For ratiometric pH calibration, treat separate cells with pre-mixed buffers (pH 4.0-7.0) containing 10 µM nigericin and 10 µM monensin (K+/H+ ionophores) for 10 min. Image the pH-sensor channel.

- Generate a standard curve of fluorescence ratio vs. pH.

Q4: My material aggregates at endosomal pH, potentially trapping the payload. How can I design for better disassembly? A: Aggregation indicates insufficient hydrophilicity switch upon protonation. Incorporate more ionizable groups (e.g., tertiary amines) into your polymer or lipid backbone. Alternatively, use a charge-conversional material (e.g., citraconyl amide) that becomes cationic at low pH, promoting endosomal escape via the proton sponge effect and reducing lysosomal entrapment.

Q5: What are the best analytical methods to quantify linker cleavage and payload release kinetics in vitro? A: Use complementary techniques:

- Dialysis or Floatation: Separate released from encapsulated payload at various time points in buffers at pH 7.4, 6.5, 5.0. Quantify via HPLC/UV-Vis.

- FRET-based Assay: If payload is fluorescent, use a FRET pair where the nanoparticle matrix is labeled with a quencher. Cleavage increases fluorescence.

- NMR Spectroscopy: Use

¹H NMRto directly observe the disappearance of linker protons in deuterated buffers at different pHs.

Table 1: Hydrolysis Half-Lives of Common pH-Cleavable Linkers

| Linker Type | Chemical Structure | Typical pH for Cleavage (t₁/₂ < 1 hr) | Approximate Half-life at pH 5.0 | Approximate Half-life at pH 7.4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrazone | R₁R₂C=N-NR₃R₄ | 4.5 - 6.0 | 10 - 60 minutes | 20 - 100 hours |

| Acetal | RCH(OR')₂ | 4.0 - 5.5 | 5 - 30 minutes | >48 hours |

| Vinyl Ether | R-O-CH=CH₂ | 4.5 - 5.5 | 2 - 15 minutes | 10 - 50 hours |

| β-Thiopropionate | R-S-CH₂CH₂-C(=O)- | 5.0 - 6.0 (intramolecular) | 30 - 120 minutes | >72 hours |

| cis-Aconityl | HOOC-CH=C(COOH)-CH₂-C(=O)- | 4.0 - 5.0 | <10 minutes | >48 hours |

Table 2: Characterization of pH-Responsive Materials

| Material Class | Example | Responsive Motif | Trigger pH | Key Advantage for Lysosomal Escape |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | DLin-MC3-DMA | Tertiary amine | ~6.5 (endosomal) | Promotes membrane disruption |

| Charge-Conversional Polymers | PAH-Cit | Citraconic amide | 5.0-6.0 | Switches anionic to cationic charge |

| PEG-Shedding Polymers | PEG-b-PASP(DET-Aco) | cis-Aconityl | <5.5 | Removes PEG shield for membrane interaction |

| Porphyrin-based MOFs | PCN-222 | Zn-Tetracarboxy-porphyrin | 5.0-6.0 | Intrinsic imaging & ROS generation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for pH-Responsive Release Experiments

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| LysoSensor Yellow/Blue DND-160 | Ratiometric, long-wavelength pH indicator for acidic organelles. |

| pHrodo Red / Green Dextran | Fluorescent dye whose intensity increases sharply in acidic pH; used for tracking phagocytosis and endosomal maturation. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor; used as a control to alkalinize endo/lysosomes and inhibit pH-dependent cleavage. |

| Chloroquine | Lysosomotropic agent that neutralizes acidic compartments; control for proton-sponge effect studies. |

| Nigericin & Monensin (K+/H+ Ionophores) | Used in high-K+ buffers to clamp intracellular pH for calibration curves. |

| HEPES & MES Buffers | For precise extracellular pH control during pulse-chase experiments. |

| Citrate-Phosphate Buffers (McIlvaine's) | Provides stable buffering across a wide pH range (2.6 to 7.8) for in vitro release studies. |

| Dialysis Membranes (MWCO 3.5-14 kDa) | For separating released small molecule payloads from nanoparticles during kinetic studies. |

Experimental Protocol

Protocol 2: Standard In Vitro Payload Release Kinetics Assay Objective: Quantify pH-dependent release from nanoparticles.

- Prepare Release Media: 30 mL each of PBS (pH 7.4), acetate buffer (pH 5.5), and acetate buffer (pH 5.0), all with 0.1% w/v Tween 80 to maintain sink conditions.

- Load Nanoparticles: Place 1.0 mL of nanoparticle suspension (1 mg/mL in PBS) into a pre-wetted dialysis tube (MWCO appropriate for payload).

- Dialyze: Immerse the dialysis bag in 30 mL of the respective release medium at 37°C with gentle stirring (100 rpm). Protect from light if payload is light-sensitive.

- Sample: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 h), remove 1 mL of the external medium and replace with 1 mL of fresh pre-warmed medium.

- Quantify: Analyze the sampled medium for payload concentration using a pre-validated HPLC or fluorescence method. Calculate cumulative release.

Visualizations

Mechanisms to Overcome Lysosomal Entrapment

pH-Responsive NP Release Validation Workflow

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My fusogenic liposome formulation shows low encapsulation efficiency for my siRNA payload. What could be the cause and how can I improve it? A: Low encapsulation efficiency (EE%) in fusogenic liposomes is often due to suboptimal lipid composition or hydration conditions. The cationic lipid DOPE is crucial for membrane fusion but can compromise stability. Ensure a balanced molar ratio. Use the ethanol injection or thin-film hydration method with a controlled pH (e.g., citrate buffer, pH 4.0) during hydration to enhance siRNA retention. Post-formation, implement a dialysis or tangential flow filtration step to remove unencapsulated siRNA effectively. Monitor EE% using a Ribogreen assay.

Q2: I observe high cytotoxicity in my target cells when using ionizable lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). How can I mitigate this? A: High cytotoxicity often stems from the cationic charge of ionizable lipids at low endosomal pH or from poorly biodegradable lipid structures. Troubleshoot by: 1) Adjusting the ionizable lipid to helper lipid ratio. Reduce the ionizable lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA) percentage and increase the structurally neutral phospholipid (DSPC) or cholesterol. 2) Evaluate next-generation biodegradable ionizable lipids (e.g., those with ester linkages). 3) Perform a comprehensive cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo) across a range of N/P (nitrogen-to-phosphate) ratios to identify the optimal, less toxic formulation window.

Q3: My LNPs exhibit poor shelf-life stability and aggregate within one week of storage at 4°C. What stabilizers or conditions should I use? A: Aggregation indicates physical instability. Implement these steps:

- Cryoprotectants: Add a cryoprotectant (e.g., 10% w/v sucrose or trehalose) before freezing. This forms a stable glassy matrix during lyophilization.

- Buffer Exchange: Store LNPs in a histidine or Tris-based buffer (pH ~7.4) with sufficient ionic strength to prevent fusion.

- Sterile Filtration: If particle size is <200 nm, use a 0.22 µm polyethersulfone (PES) membrane for sterile filtration to remove potential nucleation sites for aggregation.

- Storage: For long-term stability, store as lyophilized powder at -20°C or below. Reconstitute with sterile water or buffer just before use.

Q4: I am getting inconsistent endosomal escape efficiency across different cell lines with my fusogenic liposomes. How can I standardize this assay? A: Inconsistent escape is common due to cell line-dependent variation in endocytic pathways and lysosomal activity.

- Standardize Internalization: First, normalize cellular uptake using flow cytometry with a fluorescent lipid tag (e.g., Dil).

- Use a Quantitative Endosomal Escape Assay: Implement a Galectin-8 (Gal8) recruitment assay or a split-GFP endosomal escape assay. These provide quantifiable, image-based data.

- Control Endosomal pH: Use pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., Bafilomycin A1 to inhibit v-ATPase) as a negative control. If escape is pH-dependent, inhibition should abolish activity, confirming the mechanism.

- Protocol - Gal8 Assay: Seed cells on imaging plates. Transfect cells with a Gal8-mCherry construct 24h prior. Treat with LNPs. After 2-4h, fix cells and image. Co-localization of Gal8 puncta with fluorescently labeled LNPs indicates endosomal disruption.

Q5: During the microfluidic mixing preparation of LNPs, how do I troubleshoot the formation of particles with a polydispersity index (PDI) > 0.2? A: High PDI (>0.2) indicates a heterogeneous particle population. Key parameters to optimize in microfluidic mixing are:

- Flow Rate Ratio (FRR): Increase the aqueous-to-organic phase flow rate ratio (e.g., from 3:1 to 5:1) to accelerate mixing and nucleation.

- Total Flow Rate (TFR): Increase the TFR (e.g., from 12 mL/min to 18 mL/min) to achieve faster turbulent mixing.

- Buffer Composition: Ensure the aqueous phase (e.g., siRNA in citrate buffer) and the organic phase (lipids in ethanol) are at the same temperature (e.g., room temp) before mixing.

- Post-Formulation Processing: Immediately after mixing, dialyze or buffer-exchange to remove ethanol, which can destabilize particles. Filter through a 0.45 µm syringe filter if large aggregates are visible.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Formulation Parameters & Outcomes

| Parameter | Fusogenic Liposomes (siRNA) | Ionizable LNPs (mRNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Size Range | 80 - 150 nm | 70 - 120 nm |

| PDI Target | < 0.15 | < 0.10 |

| Encapsulation Efficiency | 70 - 90% | > 95% |

| Key Functional Lipid | DOPE (neutral, fusogenic) | DLin-MC3-DMA (ionizable) |

| N/P Ratio | 2:1 - 6:1 (N from cationic lipid) | 3:1 - 10:1 (N from ionizable lipid) |

| Optimal Storage | Lyophilized with 10% trehalose, -80°C | Lyophilized with 10% sucrose, -80°C |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Gene Knockdown (siRNA) | Lysosomal degradation, poor escape | Incorporate endosomolytic polymer (e.g., PLL) or optimize fusogenic lipid ratio. |

| High Hemolytic Activity | Excessive cationic charge at physiological pH | Reduce cationic lipid %, include PEG-lipid for shielding, perform hemolysis assay. |

| Rapid Clearance In Vivo | Opsonization and RES uptake | Increase PEG-lipid content (1-5 mol%), optimize PEG chain length (C14 vs. C18). |

| mRNA Delivery Inefficiency | mRNA degradation, incomplete translation | Ensure mRNA is cap-1 modified and poly(A)-tailed. Verify endosomal escape via co-delivery of endosomolytic agent. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for LNP Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| DLin-MC3-DMA | Industry-standard, FDA-approved ionizable lipid for in vivo mRNA delivery. Protonates in endosome to enable escape. |

| DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) | Fusogenic helper lipid that adopts a hexagonal (HII) phase at low pH, destabilizing the endosomal membrane. |

| DSPC (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) | Saturated phospholipid that provides structural integrity and bilayer stability to the nanoparticle. |

| Cholesterol | Modulates membrane fluidity and integrity, and enhances cellular uptake and stability in vivo. |

| DMG-PEG 2000 | PEG-lipid (PEG conjugated to dimyristoyl glycerol) used for surface shielding to reduce opsonization and improve circulation time. Typically incorporated at 1-2 mol%. |

| Microfluidic Mixer (e.g., NanoAssemblr, iLiNP) | Enables reproducible, scalable, and rapid mixing of lipid-ethanol and aqueous phases to form uniform LNPs via self-assembly. |

| Ribogreen Assay Kit | Fluorometric assay for quantifying encapsulated nucleic acid (siRNA/mRNA) by measuring fluorescence before and after addition of a disrupting detergent. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor used as a critical control experiment to inhibit endosomal acidification, thereby confirming pH-dependent endosomal escape mechanisms. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Microfluidic Preparation of siRNA-LNPs Objective: Formulate uniform, siRNA-encapsulating LNPs for gene silencing studies.

- Lipid Stock Prep: Dissolve ionizable lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA), DSPC, Cholesterol, and PEG-lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG2000) in ethanol at a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5. Final total lipid concentration: 10-12.5 mM.

- Aqueous Phase Prep: Dissolve siRNA in citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.0) to a concentration of 0.1-0.2 mg/mL.

- Microfluidic Mixing: Use a staggered herringbone mixer chip. Set the aqueous phase (siRNA) flow rate to 15 mL/min and the organic phase (lipids) flow rate to 5 mL/min (Total Flow Rate = 20 mL/min, FRR = 3:1). Collect the effluent in a vial.

- Buffer Exchange & Dialysis: Immediately dilute the formed LNPs 1:1 with PBS (pH 7.4). Transfer to a dialysis cassette (MWCO 3.5-10 kDa) and dialyze against 2L PBS for 4 hours, with one buffer change.

- Characterization: Measure particle size and PDI via DLS. Determine siRNA encapsulation efficiency using the Ribogreen assay.

Protocol 2: Assessing Endosomal Escape via Galectin-8 Recruitment Assay Objective: Visually quantify endosomal membrane disruption by lipid nanoparticles.

- Cell Preparation: Seed HeLa or HEK293T cells in an 8-well chambered coverslip at 70% confluency.

- Transfection: After 24h, transfect cells with a plasmid encoding Galectin-8-mCherry using a standard transfection reagent.

- LNP Treatment: 24h post-transfection, treat cells with fluorescently labeled (e.g., Cy5-lipid) LNPs. Include a positive control (e.g., Lipofectamine 2000) and a negative control (PBS).

- Inhibition Control: Pre-treat a set of cells with 100 nM Bafilomycin A1 for 1 hour before LNP addition.

- Fixation & Imaging: Incubate for 2-4 hours. Wash cells with PBS, fix with 4% PFA for 15 min, and mount with DAPI-containing medium.

- Analysis: Image using a confocal microscope. Quantify the number of Gal8-mCherry puncta that co-localize with Cy5-LNP signal per cell using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, CellProfiler).

Visualizations

Fusogenic LNP Endosomal Escape Pathway

LNP Formulation by Microfluidic Mixing

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center addresses common experimental issues within the context of advanced strategies to overcome lysosomal entrapment in nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery. The questions are framed by challenges reported in recent literature.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our porphyrin-based MOF (PMOF) shows inconsistent drug loading efficiency between batches. What are the critical parameters to control? A: Inconsistent loading often stems from variations in MOF crystallinity and pore accessibility. Ensure strict control of:

- Solvent Removal: Activate the MOF (remove solvent from pores) thoroughly before loading. Use a supercritical CO₂ dryer if available for better pore preservation.

- Synthesis Temperature: Maintain the solvothermal synthesis temperature within a ±2°C range. Crystallinity directly correlates with pore uniformity.

- Drug Solubility: Use a drug solvent that does not cause MOF decomposition. Pre-dissolve the drug in a minimal amount of solvent before adding to the MOF suspension.

- Quantitative Data from Recent Studies:

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Loading Efficiency | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Temperature | 80-120°C (under vacuum) | <80°C: Incomplete solvent removal; >120°C: Potential framework collapse | 2023 |

| Solvothermal Synthesis Time | 18-24 hours | Shorter: Poor crystallinity; Longer: No significant gain, particle aggregation | 2024 |

| Drug Incubation Time (Post-MOF) | 48-72 hours | <48h: Incomplete diffusion into pores; >72h: Risk of premature release | 2023 |

Protocol: Standardized Drug Loading into PMOFs

- Synthesize PMOF via solvothermal method (e.g., 100°C, 20h).

- Centrifuge and wash particles 3x with ethanol.

- Activate pores by heating at 100°C under vacuum (10⁻³ bar) for 12h.

- Incubate 10 mg activated PMOF with 5 mL of drug solution (2 mg/mL in anhydrous DMSO) under gentle agitation (200 rpm) for 60h at 25°C.

- Centrifuge at 15,000g for 20 min, collect pellet, and wash 2x with PBS to remove surface-adsorbed drug.

- Lyophilize the drug-loaded PMOF for storage.

Q2: The gas-generating nanoparticles (e.g., CaCO₃-based) we produce have poor dispersity and aggregate immediately in cell culture media. How can we improve colloidal stability? A: Aggregation is a common issue due to high ionic strength and protein adsorption. Solutions include:

- Surface PEGylation: Coat nanoparticles with polyethylene glycol (PEG) after drug loading but before the final wash. Use a PEG-silane or PEG-carboxylic acid suitable for your nanoparticle core material.