Controlled Drug Release from Nanocarriers: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the methods and mechanisms for achieving controlled drug release from pharmaceutical nanocarriers.

Controlled Drug Release from Nanocarriers: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the methods and mechanisms for achieving controlled drug release from pharmaceutical nanocarriers. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of drug release kinetics, details advanced methodological approaches including stimuli-responsive and targeted systems, addresses key challenges in optimization and biocompatibility, and evaluates the current landscape of preclinical and clinical validation. The synthesis of these four core intents offers a state-of-the-art resource for designing next-generation nanocarriers that enhance therapeutic efficacy and accelerate clinical application.

The Fundamentals of Controlled Release: Understanding Drug Release Mechanisms and Kinetics

A drug's therapeutic window is the specific concentration range in which it is effective without causing excessive toxicity. Concentrations below this window are ineffective, while those above it are toxic. For researchers in nanocarrier development, controlled release is the engineering discipline that actively shapes and maintains drug concentration within this critical window. It moves beyond simple drug encapsulation to the precise programming of drug release kinetics, which is fundamental to enhancing therapeutic efficacy and safety.

Conventional drug delivery systems, such as immediate-release tablets, often cause significant fluctuations in plasma drug levels. This leads to a cycle of brief therapeutic effect followed by sub-therapeutic troughs and potential peak-related side effects [1] [2]. Controlled release systems are designed to overcome these limitations by releasing the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) at a predetermined rate to maintain stable concentrations within the therapeutic window over an extended period [3]. This capability is particularly critical in fields like oncology, where many chemotherapeutic agents have a very narrow therapeutic index [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Controlled Release Experimentation

This section addresses frequent experimental hurdles and provides evidence-based solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Controlled Release Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Root Cause | Potential Solutions & Investigations |

|---|---|---|

| Bursted Release Profile | • Insufficient polymer matrix density or cross-linking [2].• Poor drug-carrier compatibility or surface adsorption [5].• Damage to the nanocarrier coating (reservoir systems) [1]. | • Increase polymer concentration or cross-linker density.• Use a different polymer or incorporate hydrophobic modifiers.• Characterize nanocarrier integrity post-synthesis via TEM/SEM [6]. |

| Incomplete or Slow Release | • Overly dense or thick polymer matrix/coating [2].• Drug instability or precipitation at local pH.• Inadequate sink conditions in release media [5]. | • Optimize polymer molecular weight or coating thickness.• Verify sink conditions (ensure volume ≥ 5-10x saturation solubility).• Incorporate enzyme or pH-responsive excipients for targeted sites [7]. |

| High Polydispersity Index (PDI) in Nanocarriers | • Aggregation or instability of nanocarriers [6].• Inconsistent mixing during synthesis.• Unoptimized purification process. | • Adjust surface charge (Zeta potential) to > ±30 mV for electrostatic stabilization [6].• Use surfactants or steric stabilizers (e.g., PEG).• Introduce a fractionation step like AF4 before DLS measurement [6]. |

| Poor Correlation Between In Vitro and In Vivo Release | • Over-simplified in vitro release media not mimicking in vivo conditions (enzymes, flow, pH gradients) [8].• Failure to account for protein binding in vivo. | • Develop a biorelevant dissolution media (correct pH, enzymes, surfactants).• Use a model that accounts for hydrodynamic conditions and binding proteins.• Consider advanced modeling (e.g., machine learning) to bridge the gap [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Release Kinetics

Protocol: Establishing a Standard In Vitro Release Study

Objective: To determine the drug release profile of a pH-responsive polymeric nanocarrier under simulated physiological and tumor microenvironment conditions.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) at pH 7.4, Acetate Buffer at pH 6.5 and pH 5.0, PBS with 0.1% w/v Tween 80 (to maintain sink conditions), dialysis membranes with appropriate molecular weight cut-off (MWCO), nanocarrier suspension.

- Equipment: USP Type II (paddle) dissolution apparatus, HPLC system with UV-Vis detector, dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument.

Methodology:

- Nanocarrier Characterization: Prior to release studies, characterize the nanocarrier batch for particle size, PDI, and zeta potential using DLS to ensure quality and reproducibility [6].

- Sink Condition Validation: Determine the solubility of the drug in each release medium. The volume of medium used should be at least 5-10 times the volume required to create a saturated solution of the drug dose.

- Release Study Setup:

- Place a precise volume of nanocarrier suspension (equivalent to a known drug dose) into a dialysis tube sealed at both ends.

- Immerse the dialysis tube in the release vessel containing a known volume (e.g., 500 mL) of pre-warmed (37°C) release medium, stirred at 50 rpm.

- Perform the study in triplicate for each pH condition (pH 7.4, 6.5, and 5.0) to simulate blood, tumor microenvironment, and endolysosomal conditions, respectively [4] [7].

- Sampling and Analysis:

- At predetermined time intervals, withdraw a known aliquot (e.g., 1 mL) from the release medium and replace it with an equal volume of fresh, pre-warmed medium to maintain sink conditions.

- Filter the withdrawn samples (0.45 µm filter) and analyze the drug concentration using a validated HPLC method.

- Continue the experiment until at least 80% of the drug has been released or a plateau is reached.

Protocol: Data Analysis and Release Kinetics Modeling

Objective: To fit experimental release data to mathematical models to identify the predominant release mechanism.

Methodology:

- Data Compilation: Calculate the cumulative percentage of drug released versus time.

- Model Fitting: Fit the release data to the following key mathematical models using statistical software. The table below summarizes the models and their interpretations [5].

Table 2: Key Mathematical Models for Analyzing Drug Release Kinetics

| Model Name | Equation | Mechanistic Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-Order | ( Qt = Q0 + k_0 t ) | Constant release rate over time, ideal for controlled release systems. ( Qt ) is the amount of drug released at time ( t ), ( k0 ) is the rate constant. |

| First-Order | ( \log Qt = \log Q0 + \frac{k_1 t}{2.303} ) | Release rate is concentration-dependent. Common for water-soluble drugs in porous matrices. |

| Higuchi | ( Qt = kH \sqrt{t} ) | Drug release from an insoluble matrix is controlled by Fickian diffusion. ( k_H ) is the Higuchi dissolution constant. |

| Korsmeyer-Peppas (Power Law) | ( \frac{Mt}{M\infty} = k t^n ) | Empirically describes drug release from polymeric systems. The release exponent ( n ) indicates the release mechanism (e.g., Fickian diffusion, Case-II transport, anomalous transport) [5]. |

- Model Selection: The best-fit model is typically selected based on the highest correlation coefficient (R²) and the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The Korsmeyer-Peppas model is particularly useful for identifying the underlying release mechanism in the initial 60% of release.

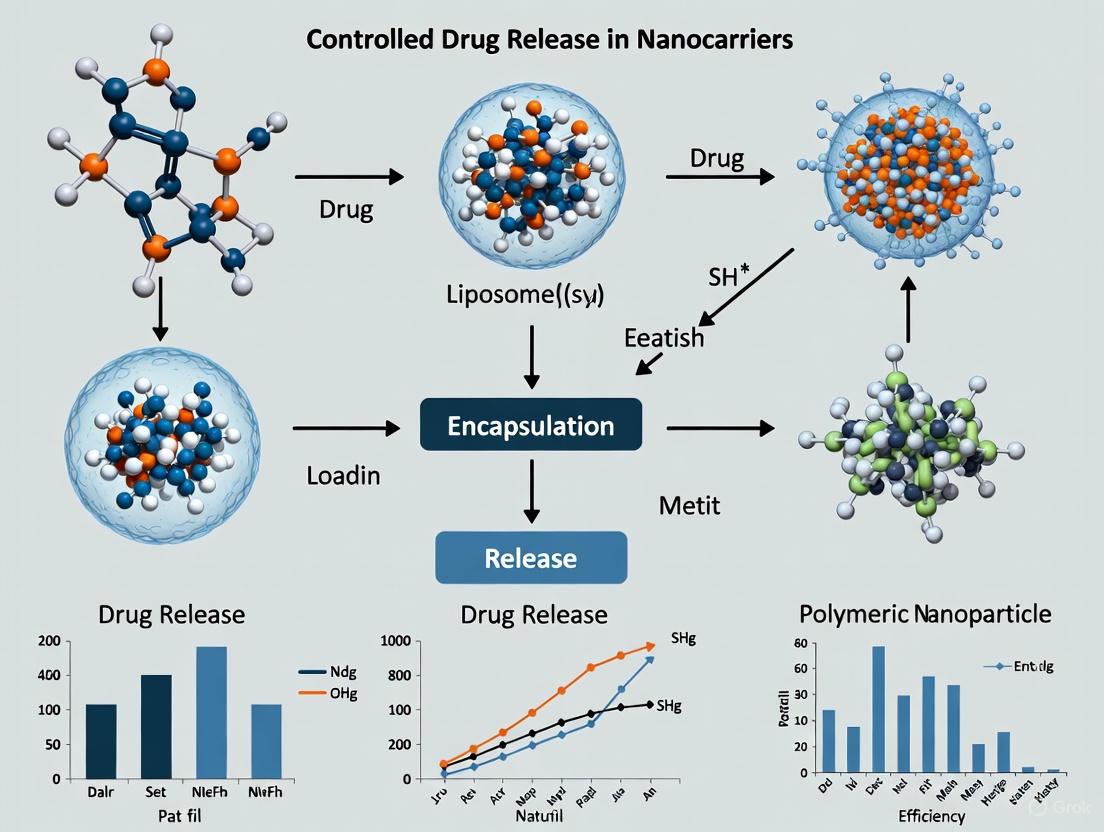

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing and characterizing a controlled-release nanocarrier system, from formulation to data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Controlled Release Nanocarrier Development

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| pH-Sensitive Polymers | Backbone of nanocarriers that degrade or swell in response to acidic pH (e.g., tumor microenvironment, endosomes). Enable targeted drug release [4] [7]. | Poly(L-histidine), Eudragit series (S100, L100), Poly(β-amino esters). |

| Ionizable Lipids | Critical component of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). Their headgroup protonation/deprotonation in different pH environments can facilitate endosomal escape and content release [4] [10]. | DLin-MC3-DMA, ALC-0315. |

| Hydrophilic Polymers | Used to create gel-forming matrix tablets or as stealth coatings on nanocarriers to reduce opsonization and prolong circulation half-life [1] [2]. | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). |

| Enzyme-Sensitive Linkers | Cross-linkers or building blocks that are cleaved by enzymes overexpressed in disease sites (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases in tumors). Provide a biological trigger for release [7]. | MMP-cleavable peptides (e.g., GPLG↓VRG), hyaluronic acid (cleaved by hyaluronidase). |

| Osmotic Agents | Core component in osmotic pump systems. They generate osmotic pressure to push the drug solution out through a laser-drilled orifice at a constant rate, independent of environmental pH [1]. | Sodium chloride, potassium phosphate, sucrose. |

| Targeting Ligands | Molecules attached to the nanocarrier surface to facilitate active targeting to specific cell types via receptor-mediated endocytosis, enhancing site-specific release [4] [7]. | Folate, monoclonal antibodies, transferrin, peptides (e.g., RGD). |

Advanced Topics: Integrating Machine Learning and Pathway Analysis

Machine Learning in Release Kinetics Prediction

Traditional mathematical models are powerful but can struggle with the complexity of multi-stimuli responsive systems. Machine learning (ML) is emerging as a robust tool for modeling and predicting drug release. A recent study demonstrated that ML regression models like Decision Tree Regression (DTR) can achieve exceptional predictive accuracy (R² > 0.99) for drug release from complex polymeric matrices by learning from large datasets generated via computational fluid dynamics (CFD) [9]. This data-driven approach can significantly accelerate the formulation optimization process.

Molecular Pathways in Colorectal Cancer and Nanocarrier Design

Understanding disease-specific molecular pathways is crucial for designing intelligent, targeted nanocarriers. The following diagram outlines key pathways in Colorectal Cancer (CRC) that can be exploited for controlled release, illustrating the connection between molecular biology and delivery system engineering.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between "Extended Release" (ER) and "Controlled Release" (CR)? While often used interchangeably, there is a technical distinction. Extended-release (ER) is a broad term for any dosage form that prolongs the release of an API. Controlled-release (CR) is a specific type of ER designed to release the drug at a constant, predetermined rate (zero-order kinetics) by using advanced mechanisms like osmotic pumps, maintaining plasma levels within the therapeutic window with minimal fluctuation [1].

Q2: Why is my nanocarrier formulation showing high batch-to-batch variability in release profiles? Inconsistent physicochemical properties like particle size and PDI are the most common culprits. Strict control over synthesis parameters (e.g., mixing speed, solvent addition rate, temperature) and purification processes is essential. Implement rigorous in-process controls and characterize every batch for size, PDI, and zeta potential using DLS before proceeding to release studies [6].

Q3: How can I determine if my nanocarrier's release mechanism is diffusion- or erosion-controlled? Fit your release data to the Korsmeyer-Peppas model. The release exponent (n) value provides insight. For spherical matrices, an n ≈ 0.43 suggests Fickian diffusion, while n ≈ 0.85 indicates Case-II transport (relaxation/erosion controlled). An n value between 0.43 and 0.85 signifies anomalous transport, a combination of both diffusion and erosion [5].

Q4: Our in vitro release data looks excellent, but the in vivo efficacy is poor. Where should we focus our investigation? This disconnect often arises from biological barriers not accounted for in in vitro tests. Key areas to investigate are:

- Protein Corona: Serum proteins adsorb onto nanocarriers in vivo, altering their surface properties and targeting capability [6] [10].

- Premature Clearance: The mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) may rapidly clear nanocarriers. Consider modifying the surface with "stealth" coatings like PEG.

- Biological Sink: The drug may be rapidly distributed, metabolized, or cleared in vivo, preventing local accumulation.

Q5: Are there strategies to create a multi-pulsed (chronotherapeutic) release profile from a single nanocarrier system? Yes, this is an advanced area of research. Strategies include:

- Multi-layered Systems: Coating drug cores with polymers of different thicknesses and degradation rates.

- Pulsatile Systems: Using a rupturable coating that dissolves after a specific time lag.

- Multi-Material Nanocarriers: Designing particles with a core-shell structure where each compartment responds to a different stimulus (e.g., pH then enzyme), resulting in staged release [2].

In pharmaceutical nanotechnology, controlling the release of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is fundamental to enhancing therapeutic efficacy and reducing systemic side effects. Controlled-release nanocarriers are designed to deliver drugs in a spatiotemporally controlled manner, which helps maintain drug concentration within the therapeutic window—between the minimum effective concentration (MEC) and the minimum toxic concentration (MTC) [11]. The primary mechanisms governing this controlled release are diffusion-controlled, solvent-controlled, and degradation-controlled release. For researchers developing nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems (DDS), a deep understanding of these mechanisms is critical for rational design and overcoming common experimental challenges. This guide provides a technical foundation and practical troubleshooting support for investigating these core release mechanisms.

Core Drug Release Mechanisms: Principles and Analysis

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, driving forces, and typical release profiles of the three primary drug release mechanisms.

Table 1: Fundamental Drug Release Mechanisms in Nanocarriers

| Mechanism | System Design | Driving Force | Release Kinetics | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion-Control [11] [12] | Reservoir system (drug core surrounded by polymer membrane) or Matrix system (drug dispersed in polymer matrix) | Concentration gradient across the polymer barrier [11] | First-order (matrix); Zero-order (reservoir, ideal case) [11] | Membrane thickness, drug solubility, polymer porosity, diffusion coefficient [11] |

| Solvent-Control [11] | Osmotic pumps (semi-permeable membrane) or Swelling systems (glassy hydrophilic polymers) | Osmotic pressure gradient or Water absorption/polymer swelling [11] | Zero-order (osmosis); Often complex, can be zero-order (swelling) [11] | Membrane permeability, osmotic pressure, polymer relaxation rate, cross-link density [11] |

| Degradation-Control [11] | Systems comprising biodegradable polymers (e.g., polyesters, polyamides) | Chemical or enzymatic cleavage of polymer chains [11] | Often correlated with degradation rate (e.g., first-order, biphasic) | Polymer crystallinity, molecular weight, pH, enzyme concentration [11] |

Diffusion-Controlled Release

Diffusion is a mass transport process where particles move from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration [13]. In nanocarriers, this mechanism is governed by Fick's laws of diffusion [13].

- Fick's First Law describes the steady-state flux (J):

J = -D (dC/dx), whereDis the diffusion coefficient, anddC/dxis the concentration gradient [13]. - Fick's Second Law describes how the concentration changes with time at a definite location:

∂C/∂t = D (∂²C/∂x²)[13].

Two main types of diffusion-controlled systems are prevalent:

- Reservoir Systems (Membrane Systems): The drug is contained in a core surrounded by a polymeric membrane. Drug release is controlled by diffusion through this rate-controlling membrane [11] [12].

- Matrix Systems (Monolithic Systems): The drug is uniformly dispersed or dissolved throughout a polymer matrix. Release occurs as the drug diffuses from the matrix to the surrounding medium [11] [12].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental principles of the diffusion-controlled release mechanism.

Solvent-Controlled Release

This mechanism relies on the transport of solvent (typically water) into the drug carrier. It is subdivided into two categories:

- Osmosis-Controlled Release: The system is encapsulated by a semi-permeable membrane. Water flows into the core due to an osmotic gradient, building up internal pressure that pushes the drug solution out through a laser-drilled orifice [11] [12]. This mechanism can achieve a constant (zero-order) release rate [11].

- Swelling-Controlled Release: This involves glassy, hydrophilic polymers. Upon contact with water, the polymer swells as water diffuses in, transitioning from a glassy to a rubbery state. The drug then diffuses out through the swollen polymer network. The release rate depends on both the water diffusion rate and the polymer chain relaxation rate [11].

The diagram below outlines the sequential process of solvent-controlled release.

Degradation-Controlled Release

In this mechanism, drug release is regulated by the chemical breakdown of the carrier material itself. Biodegradable polymers, such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and other polyesters, are commonly used. Degradation can occur via:

- Bulk Erosion: The polymer degrades uniformly throughout the matrix.

- Surface Erosion: Degradation is confined to the surface of the device, which can lead to a more constant release rate.

The degradation process itself can be driven by hydrolysis (cleavage of chemical bonds by water) or by enzymatic activity in the target environment [11].

Essential Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Investigation

Protocol: In Vitro Drug Release Kinetics Study

Objective: To characterize and model the drug release profile from a nanocarrier formulation under simulated physiological conditions.

Materials:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4: Standard dissolution medium simulating physiological pH [11].

- Dialysi s Bag or Membrane: Acts as a barrier between the nanocarrier suspension and the release medium, simulating a diffusion path [6].

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer or HPLC: For quantitative analysis of drug concentration in the release medium [6].

- Stirring Plate and Water Bath: To maintain constant temperature (e.g., 37°C) and hydrodynamics (sink conditions) [6].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Place a known volume of nanocarrier suspension (with precise drug content) into a pre-hydrated dialysis bag. Seal the bag securely.

- Dissolution Setup: Immerse the dialysis bag in a vessel containing a sufficient volume of pre-warmed PBS (37°C) to maintain sink conditions. Ensure constant, gentle agitation.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals, withdraw a fixed aliquot of the release medium from the vessel.

- Replenishment: Immediately replace the withdrawn volume with fresh, pre-warmed PBS to maintain a constant volume and sink conditions.

- Analysis: Quantify the drug concentration in each aliquot using a pre-validated analytical method (e.g., UV-Vis at λ_max, HPLC).

- Data Processing: Calculate the cumulative drug release (%) versus time. Plot the release profile and fit the data to various mathematical models (e.g., Zero-order, First-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to identify the predominant release mechanism [11].

Protocol: Nanocarrier Physicochemical Characterization

Objective: To determine key physical properties of the nanocarrier that directly influence its release behavior and performance.

Materials:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument: For measuring particle size, size distribution (PDI), and zeta potential [6].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) or Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): For visualizing particle morphology, size, and structure [6].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): For high-resolution topographical imaging of nanocarriers [6].

Methodology:

- Particle Size & PDI: Dilute the nanocarrier suspension appropriately with a filtered solvent (e.g., water). Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and PDI using DLS. A PDI value <0.3 is generally considered acceptable for a monodisperse system [6].

- Zeta Potential: Dilute the sample and measure the electrophoretic mobility to determine zeta potential, which indicates colloidal stability. Values greater than ±30 mV typically suggest good physical stability [6].

- Morphology: Deposit a diluted drop of nanocarrier suspension onto a TEM grid or SEM stub. Allow to dry and image under the microscope to confirm the DLS size data and observe the shape and surface characteristics [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Table 2: Frequently Encountered Problems and Solutions in Release Studies

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Burst Release [11] | Drug adsorbed on or near the particle surface; Inadequate encapsulation; Fast water penetration. | Modify preparation method to enhance encapsulation efficiency; Increase polymer wall thickness; Use a hydrophobic coating or cross-linking [11]. |

| Incomplete Release | Poor drug solubility in release medium; Insufficient degradation of polymer; Drug-polymer interactions. | Incorporate solubilizing agents (e.g., surfactants) in the release medium; Use polymers with faster degradation kinetics; Optimize drug-polymer compatibility [11]. |

| Irreproducible Release Profiles | Inconsistent nanocarrier batch quality (size, PDI); Aggregation during release study; Variable experimental conditions. | Standardize nanocarrier synthesis and purification protocols; Include stabilizers to prevent aggregation; Strictly control temperature, pH, and agitation speed [6]. |

| Deviation from Expected Kinetics | Complex, overlapping release mechanisms (e.g., diffusion and swelling); Changes in carrier structure during release. | Conduct release studies under different conditions (e.g., pH, enzyme presence) to deconvolute mechanisms; Use microscopy (SEM/TEM) to observe structural changes post-release [11] [6]. |

| Nanocarrier Instability | Low zeta potential leading to aggregation; Chemical degradation during storage; Ostwald ripening. | Optimize formulation to increase surface charge; Lyophilize with appropriate cryoprotectants; Store under inert conditions and appropriate temperature [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Controlled-Release Nanocarrier Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers (e.g., PLGA, PLA) | Form the degradable matrix or membrane of the nanocarrier, controlling release rate [11]. | Matrix systems for sustained release; Micro/Nanospheres for encapsulation [11]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Surface coating agent to impart "stealth" properties, reducing opsonization and extending circulation half-life [11]. | PEGylation of liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles to enhance passive targeting via the EPR effect [11]. |

| Lipids (Phospholipids, Cholesterol) | Building blocks for lipid-based nanocarriers like liposomes and solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) [6]. | Forming biocompatible vesicles for encapsulating hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs [6]. |

| Targeting Ligands (e.g., Folate, Antibodies, Peptides) | Surface functionalization moieties for active targeting to receptors overexpressed on specific cells [11] [7]. | Functionalizing nanoparticles for targeted delivery to cancer cells (e.g., folate for CRC cells) [11] [7]. |

| Disintegrants & Porogens (e.g., Crospovidone, NaCl) | Agents that create channels or cause the structure to break apart, facilitating drug release [14]. | Incorporated into matrix systems to modify release profiles from diffusion-controlled to erosion-controlled [14]. |

FAQ: Addressing Critical Research Questions

Q1: How can I differentiate between diffusion-controlled and degradation-controlled release in my experimental data? A: Fit your release data to mathematical models. A good fit to the Higuchi model (cumulative release ∝ √time) often suggests a diffusion-controlled mechanism from a matrix system. For degradation control, monitor both mass loss of the polymer and drug release; if they correlate closely, degradation is likely the primary driver. Additionally, observe the carrier morphology post-release—significant structural disintegration points toward degradation-control [11].

Q2: My nanocarrier formulation shows high initial burst release. How can I mitigate this? A: Burst release is often caused by poorly encapsulated drug or drug crystals on the surface. Solutions include: 1) Optimizing your preparation method (e.g., double emulsion for hydrophilic drugs) to improve encapsulation efficiency. 2) Applying a sealing or coating layer (e.g., with a polyelectrolyte or polymer shell). 3) Washing the final nanocarrier product thoroughly to remove surface-bound drug [11].

Q3: Why is achieving zero-order (constant rate) release kinetics challenging with nanocarriers? A: The high surface-area-to-volume ratio of nanocarriers makes them prone to initial rapid release. True zero-order release requires the release area and the concentration gradient to remain constant, which is difficult to maintain in a shrinking or degrading nanoparticle. Reservoir systems (nanocapsules) and swelling-controlled systems that exhibit a constant moving diffusion front are your best candidates for approaching zero-order kinetics [11].

Q4: How does the nanocarrier's size and surface charge influence drug release? A: Size: Smaller particles have a larger surface area for diffusion, which can lead to a faster initial release rate. Surface Charge (Zeta Potential): A high zeta potential (positive or negative) improves colloidal stability by preventing aggregation. If particles aggregate during the release study, the effective surface area changes, leading to altered and irreproducible release kinetics [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary goal of achieving zero-order release kinetics in a drug delivery system?

Zero-order release describes a system where the drug is released at a constant rate, independent of its concentration [15]. This is the ultimate goal for many controlled-release systems because it maintains a stable, therapeutic concentration of the drug in the blood for a prolonged period [15] [5]. This leads to better patient compliance, reduces the frequency of drug administration, and minimizes the risk of side effects caused by plasma concentration fluctuations, which is especially critical for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index [15].

Q2: When should I use the Korsmeyer-Peppas model over other release kinetic models?

The Korsmeyer-Peppas model is particularly useful when the exact drug release mechanism from a polymeric system is unknown or when multiple release phenomena are involved [16] [17] [18]. It is a semi-empirical model that is often applied to analyze the first 60% of the release curve to understand the underlying transport mechanism [17]. Its strength lies in its ability to analyze non-Fickian diffusion, which is common in polymeric systems, by using a diffusional exponent, 'n', to provide insight into the release mechanism [15] [18].

Q3: My release data shows an initial burst release. Is this normal for nanocarrier systems?

Yes, an initial burst release is a common characteristic of many nanocarrier systems, including those made from polymers like PLGA [17]. This often occurs due to the rapid release of drug molecules attached to the surface or residing in the peripheral layers of the nanoparticle [17]. Following this initial burst, a slower, more sustained release phase is typically observed, which is often dominated by the diffusion of the drug through the polymer matrix and the subsequent degradation of the polymer itself [17].

Q4: How do I determine if my drug release is controlled by Fickian diffusion or other mechanisms using the Korsmeyer-Peppas model?

The value of the release exponent 'n' in the Korsmeyer-Peppas model is used to interpret the release mechanism. For a thin film formulation, the general interpretation is as follows [15] [19]:

- n = 0.5: Indicates Fickian diffusion, where release is controlled by the concentration gradient.

- 0.5 < n < 1.0: Indicates non-Fickian or anomalous transport, where release is governed by a combination of diffusion and polymer relaxation.

- n = 1.0: Indicates Case-II transport, which is purely relaxation-controlled.

- n > 1.0: Indicates super Case-II transport. It is crucial to consult literature for the specific 'n' values corresponding to your delivery system's geometry (e.g., spherical, cylindrical) [16].

Q5: Why is my drug release profile not fitting well with any standard kinetic model?

Poor model fitting can occur for several reasons. The release process may be complex, involving a combination of diffusion, swelling, and erosion mechanisms that a single model cannot capture [19]. The model might be applied outside its valid range; for example, the Korsmeyer-Peppas model is recommended only for the first 60% of the release data [17]. Furthermore, specific experimental conditions, such as changes in osmotic stress or ionic strength in the release medium, can significantly alter the release kinetics, leading to non-linear profiles that are difficult to fit with simple models [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Failure to Achieve Zero-Order Release Profile

Problem: The drug release rate from your matrix system decreases over time, showing first-order kinetics instead of the desired constant, zero-order release.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient multi-diffusion pathways | Incorporate a combination of release-controlling polymers with different characteristics. For example, use methacrylic acid copolymers (e.g., Eudragit) in combination with a swellable polymer like HPMC to create a homogenous, intermeshing gel structure that provides a multi-step diffusion system [15]. |

| Poorly controlled reservoir system | For reservoir-type devices, ensure the coating membrane is uniform and acts as a true rate-controlling barrier. The core should function as a saturated drug reservoir. Optimize the coating process and the permeability of the polymer membrane [15] [19]. |

| Rapid erosion of the matrix | If using an erodible system, adjust the polymer composition and ratio to slow down the erosion process. Using a non-eroding polymer network that is formed by heat curing can provide a more stable structure for constant release [15]. |

Issue 2: Interpreting the Diffusional Exponent (n) in the Korsmeyer-Peppas Model

Problem: You have calculated the 'n' value but are unsure how to interpret it for your specific drug delivery system.

| System Geometry | n value for Fickian Diffusion | n value for Case-II Transport (Polymer Relaxation) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thin Film | 0.5 | 1.0 | [15] [19] |

| Cylinder | 0.45 | 0.89 | [19] |

| Sphere | 0.43 | 0.85 | [19] |

Action Plan:

- Confirm Geometry: First, correctly identify the geometry of your drug delivery system (e.g., a spherical nanoparticle, a cylindrical implant, or a thin film).

- Refer to Table: Use the table above to find the critical 'n' values for your system's geometry.

- Interpret Mechanism: Compare your calculated 'n' value to the reference values.

- If n is equal to the Fickian diffusion value, release is diffusion-controlled.

- If n is between the Fickian and Case-II values, release is anomalous (a combination of diffusion and relaxation).

- If n is equal to the Case-II value, release is controlled by polymer relaxation/swelling [19].

Issue 3: Managing Burst Release from Polymeric Nanoparticles

Problem: Your polymeric nanoparticle formulation exhibits a significant initial burst release, depleting a large portion of the drug too quickly.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Drug adsorbed on the surface | Modify the synthesis technique or include a washing step after nanoparticle formation to remove surface-bound drug molecules [17]. |

| High porosity and fast water penetration | Optimize the formulation by adjusting the polymer molecular weight, lactide/glycolide (LA:GA) ratio in PLGA, or adding excipients to reduce initial porosity and slow down water ingress [17]. |

| Low drug-polymer interaction | Consider functionalizing the polymer or the drug to promote stronger interactions, thereby reducing the diffusion of drug molecules near the surface [17]. |

Key Mathematical Models for Release Kinetics

The table below summarizes the most common mathematical models used to analyze in-vitro drug release data.

| Model Name | Equation | Application & Release Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-Order | Q<sub>t</sub> = Q<sub>0</sub> + K<sub>0</sub>t [15] |

Describes systems where drug release is constant over time (ideal for controlled release). Release rate is independent of drug concentration [15] [5]. |

| First-Order | ln Q<sub>t</sub> = ln Q<sub>0</sub> + K<sub>1</sub>t [17] |

Describes systems where the release rate is concentration-dependent. The release rate declines over time as the drug concentration in the dosage form decreases [15] [5]. |

| Higuchi | Q = K<sub>H</sub>t<sup>1/2</sup> [15] [5] |

Describes drug release from an insoluble matrix as a square root of time-dependent process based on Fickian diffusion. It is often used for systems where the drug is dispersed in a solid matrix [15] [5]. |

| Korsmeyer-Peppas | M<sub>t</sub>/M<sub>∞</sub> = Kt<sup>n</sup> [16] [17] |

A semi-empirical model used to analyze the release mechanism from polymeric systems when the mechanism is unknown or more than one phenomenon is involved. The diffusional exponent 'n' characterizes the release mechanism [15] [16]. |

| Hixson-Crowell | Q<sub>0</sub><sup>1/3</sup> - Q<sub>t</sub><sup>1/3</sup> = K<sub>HC</sub>t [15] |

Describes release from systems where the surface area and diameter of the drug particles change over time, such as in erodible systems [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of Multi-Step Diffusion-Based Matrix Tablets for Zero-Order Release

This protocol is adapted from a study aiming to achieve pH-independent, zero-order release for a freely water-soluble drug [15].

1. Materials and Equipment:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API): Freely water-soluble model drug.

- Release-Controlling Polymers: Eudragit RS/RL and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) K100M.

- Excipients: Colloidal silicon dioxide (glidant), calcium phosphate dibasic dihydrate (disintegrant), microcrystalline cellulose and lactose monohydrate (diluents), magnesium stearate (lubricant).

- Granulating Solution: Polyvinyl pyrolidone (PVP) K30 (binder) and triethyl citrate (TEC, plasticizer) in solvent.

- Equipment: Planetary mixer, wet granulation equipment, drying oven, tablet compression machine, coating pan.

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Dry Blending. Screen the API, polymers (Eudragit RS/RL, HPMC), and all excipients (except lubricant) through a 20-mesh sieve. Dry blend them in a planetary mixer [15].

- Step 2: Wet Granulation. Wet the blended mixture with a binder solution comprising PVP K30 and triethyl citrate. This aids in granule formation [15].

- Step 3: Drying and Lubrication. Dry the resulting wet granules. Afterwards, blend the dried granules with the lubricant (magnesium stearate) [15].

- Step 4: Compression. Compress the final blend into round tablets with a target hardness of approximately 15 KP [15].

- Step 5: Heat Curing. Heat cure the core tablets at 35°C for two hours. This critical step allows the methacrylic acid copolymers to form a structure that entraps the drug molecules, creating a multi-diffusional network [15].

- Step 6: (Optional) Coating. For further release control, the core tablets can be coated with a minimal weight gain (e.g., 5% w/w) of a controlled-release polymer membrane (e.g., Eudragit RS/RL). The coated tablets must also be dried and cured at 35°C for two hours [15].

3. Release Kinetics Analysis:

- Use USP Apparatus II (paddle method) at 100 rpm with sequential dissolution media (e.g., 2 hours at pH 1.2 followed by 10 hours at pH 6.8) to obtain the drug release profile [15].

- Fit the cumulative release data to various kinetic models (Zero-order, First-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to analyze the release mechanism and confirm the achievement of zero-order kinetics [15].

Protocol 2: Analyzing Drug Release from Liposomes using the Korsmeyer-Peppas Model

This protocol outlines the use of the Korsmeyer-Peppas model to interpret non-linear drug release data from liposomes, which can be affected by the external environment [16].

1. Materials and Equipment:

- Liposomal Formulation: Large unilamellar vesicle (LUV) dispersions.

- Drugs: Hydrophilic (e.g., caffeine) and lipophilic (e.g., hydrocortisone) drugs.

- Release Media: Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) of varying ionic strengths/tonicity (e.g., 65 mOsm/kg and 300 mOsm/kg) to simulate osmotic stress.

- Dialysis Barriers: Low-retention barriers (e.g., regenerated cellulose membrane) and high-retention barriers (e.g., Permeapad).

- Equipment: Dialysis apparatus, UV-Vis spectrophotometer or HPLC for drug quantification.

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Liposome Preparation and Characterization. Prepare LUV dispersions using a method like thin-film hydration and extrusion. Characterize the liposomes for size, polydispersity index (PDI), zeta potential (ZP), and encapsulation efficiency (EE) [16].

- Step 2: In Vitro Release Study. Place the liposomal dispersion in the donor compartment of a dialysis device. The acceptor compartment contains the release medium (PBS). Maintain the system under sink conditions where possible [16].

- Step 3: Sampling. At predetermined time intervals, withdraw samples from the acceptor compartment and replace with fresh medium to maintain volume. Analyze the samples for drug concentration [16].

- Step 4: Data Collection. Calculate the cumulative amount of drug released (

M_t) and the fractional release (M_t / M_∞) over time, whereM_∞is the total amount of drug released at the end of the experiment.

3. Data Fitting with Korsmeyer-Peppas Model:

- Input the fractional release (

M_t / M_∞) and time (t) data into non-linear regression software. - Fit the data to the Korsmeyer-Peppas equation:

M_t / M_∞ = K * t^n[16]. - Obtain the release constant (K) and the release exponent (n).

- Interpret the value of 'n' to understand the drug release mechanism from the liposomes under different osmotic conditions [16].

Experimental Workflow and Model Selection

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for selecting and applying kinetic models to analyze drug release data.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials used in the featured experiments for developing controlled release dosage forms.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Methacrylic Acid Copolymers (Eudragit RS/RL) | Non-eroding, pH-independent release-controlling polymers that form a permeable membrane for drug diffusion. RL is more permeable than RS [15]. | Used in matrix tablets to create a multi-diffusional network for zero-order release of freely soluble drugs [15]. |

| Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) | A swellable hydrophilic polymer that forms a gel layer upon hydration, controlling drug release through diffusion and erosion [15]. | Combined with Eudragit polymers to form a homogenous, intermeshing gel structure in matrix tablets [15]. |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A biodegradable polymer used in nanocarriers. Release kinetics can be controlled by adjusting its molecular weight and LA:GA ratio [17]. | Used in nanoparticles for sustained release; shows biphasic release (initial burst followed by slow release) [17]. |

| Triethyl Citrate (TEC) | A plasticizer used to improve the flexibility and processability of polymeric films, especially in coating formulations [15]. | Added to the granulating solution and coating suspension for Eudragit-based tablets to ensure a stable film structure [15]. |

| Cholesterol | A membrane-stabilizing agent incorporated into liposomal bilayers to increase rigidity and reduce permeability, thereby modulating drug release [16]. | Added to liposome formulations to study its effect on release kinetics under different osmotic stress conditions [16]. |

Nanocarriers have emerged as powerful tools in controlled drug delivery, offering the potential to enhance therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic side effects. However, their extremely high surface area to volume ratio—a fundamental property at the nanoscale—presents both a significant opportunity and a substantial challenge for controlling drug release profiles. While this property enables greater interaction with biological environments and enhanced functionality, it also creates a strong tendency for rapid drug release due to the short diffusion distance and extensive surface area exposed to the surrounding medium [11] [20]. This technical guide addresses the common challenges researchers face when working with nanocarrier drug release profiles and provides practical methodologies to overcome them.

Technical FAQs: Addressing Research Challenges

Q1: Why do my nanocarriers consistently show high burst release, and how can I mitigate this?

High initial burst release occurs when drug molecules located at or near the nanoparticle surface rapidly dissolve and diffuse into the surrounding medium. This is primarily due to the large surface area and short diffusion path inherent to nanoscale systems [11] [21].

Solutions:

- Implement core-shell structures: Create a physical barrier using polymer membranes to control diffusion rates [11]

- Modify surface properties: PEGylation creates a hydrophilic layer that can slow initial drug release while improving circulation time [11] [20]

- Optimize drug-polymer interactions: Increase hydrophobic interactions or incorporate specific binding motifs to strengthen drug retention

- Adjust manufacturing parameters: Modify solvent removal rates and emulsification conditions to promote more uniform drug distribution

Q2: What are the limitations of dialysis methods for measuring nanocarrier drug release, and what alternatives exist?

Traditional dialysis methods often underestimate burst release and provide inaccurate release kinetics due to several factors [21]:

| Limitation | Impact on Release Data |

|---|---|

| Slow drug permeation through membrane | Masks true burst release kinetics |

| Potential saturation inside dialysis bag | Creates non-sink conditions, altering release rates |

| Lack of internal agitation | Allows drug/particle sedimentation and membrane fouling |

| Continuous concentration gradient disruption | Prevents accurate kinetic measurements |

Superior Alternatives:

- NanoDis System: Uses tangential flow filtration (TFF) with hollow fiber membranes to rapidly separate nanoparticles from dissolved drug, providing more accurate burst release characterization [21]

- Centrifugal ultrafiltration: Faster separation than dialysis but may risk particle damage at high speeds [21]

- In-situ UV measurement with scattering correction: Direct measurement in nanoparticle suspension without separation [21]

Q3: How does nanoparticle size specifically impact drug release kinetics?

The relationship between size and release kinetics involves multiple interacting factors:

Q4: What mathematical models are most appropriate for analyzing nanocarrier release data?

Several mathematical models can describe drug release kinetics from nanocarriers, each with specific applications and limitations [11] [20]:

| Model | Application | Release Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-order | Ideal sustained release | Constant release rate independent of drug concentration |

| First-order | Diffusion-dominated systems | Release rate proportional to drug concentration |

| Higuchi | Matrix systems | Drug release by diffusion through the matrix |

| Korsmeyer-Peppas | Polymeric systems | Determines release mechanism (Fickian/non-Fickian) |

| Hixson-Crowell | Erosion-controlled systems | Release via surface erosion and particle dissolution |

The Korsmeyer-Peppas model (Mt/M∞ = ktⁿ) is particularly valuable for identifying the dominant release mechanism through the release exponent 'n' [11].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Controlled Release Nanocarrier Fabrication and Evaluation

Objective: Synthesize PLGA nanocarriers with modified release profiles and characterize their release kinetics using validated methods.

Materials and Reagents:

- PLGA (50:50 lactic:glycolic acid): Biodegradable polymer matrix [21]

- Dichloromethane (DCM): Organic solvent for oil-in-water emulsion

- Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA): Stabilizer and emulsifying agent

- Drug compound: Model compounds (all-trans retinoic acid, doxorubicin)

- Dialysis membrane (MWCO 12-14 kDa): Traditional release assessment [21]

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS): Release medium simulating physiological conditions

- HPLC system with UV detection: Drug quantification

Procedure:

- Nanoparticle Preparation:

- Dissolve 100 mg PLGA and 10 mg drug in 5 mL DCM

- Emulsify in 20 mL aqueous PVA solution (1% w/v) using probe sonication

- Stir overnight to evaporate organic solvent

- Collect nanoparticles by centrifugation and wash twice with distilled water

Release Study Setup:

- Suspend 10 mg drug-loaded nanoparticles in 50 mL PBS (pH 7.4)

- Maintain at 37°C with constant agitation

- At predetermined intervals, separate nanoparticles via:

- Analyze drug concentration using validated HPLC method

Data Analysis:

- Calculate cumulative drug release (%) vs. time

- Fit data to multiple mathematical models

- Determine release mechanism from best-fit model

Protocol 2: Surface Modification to Modulate Release Profiles

Objective: Implement PEGylation strategy to reduce burst release and prolong circulation time.

Procedure:

- Surface Functionalization:

- Prepare PLGA nanoparticles as above

- Add mPEG-NHS ester (10 mol% relative to polymer) to nanoparticle suspension

- React for 4 hours at room temperature with gentle stirring

- Purify by centrifugation and characterize surface modification

- Release Comparison:

- Conduct parallel release studies with unmodified and PEGylated nanoparticles

- Compare burst release (% released at 1 hour) and overall release profile

- Evaluate the impact on release kinetics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent/Category | Function in Nanocarrier Research | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | Form nanoparticle matrix; control degradation rate | PLGA, PLA, PCL; Adjust lactide:glycolide ratio to modify release [11] [21] |

| Surface Modifiers | Reduce burst release; improve stability; enhance targeting | PEG derivatives, polysorbates, poloxamers; PEGylation extends circulation half-life [11] [20] |

| Characterization Tools | Quantify size, surface charge, and drug release | DLS, Zeta Potential, HPLC, TFF systems; NanoDis provides accurate release data [21] |

| Stimuli-Responsive Materials | Enable triggered release at target site | pH-sensitive polymers, thermoresponsive materials, enzyme-cleavable linkers [11] |

| Model Drug Compounds | Benchmark release kinetics under development | All-trans retinoic acid, doxorubicin, fluorescent markers; RA used in neural differentiation studies [21] |

Advanced Troubleshooting: Complex Release Profile Issues

Problem: Inconsistent release profiles between batches

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Characterize size distribution: Use DLS to ensure consistent nanoparticle size between batches

- Analyze drug loading efficiency: Variations in encapsulation efficiency significantly impact release kinetics

- Standardize purification methods: Incomplete removal of unencapsulated drug causes artificially high burst release

- Control manufacturing parameters: Precisely regulate solvent evaporation rates and mixing conditions

Problem: Achieving zero-order release kinetics from nanocarriers

Implementation Strategies:

- Core-shell architectures: Create reservoir systems with rate-controlling membranes [11]

- Multilayer nanoparticles: Incorporate successive polymer layers with different permeability

- Hybrid particle designs: Combine rapid and slow-release compartments within single systems

- Swelling-controlled systems: Utilize hydrophilic polymers that control release through hydration kinetics [11]

Visualization: Experimental Workflow for Release Study

The high surface area of nanocarriers presents a fundamental challenge in controlled drug delivery that requires multidisciplinary approaches. Through careful design strategies including surface modification, advanced characterization techniques, and appropriate mathematical modeling, researchers can transform this challenge into an opportunity for developing optimized nanocarrier systems with precisely controlled release profiles. The methodologies and troubleshooting approaches outlined in this guide provide a foundation for addressing the complex interplay between nanoscale properties and drug release behavior in pharmaceutical development.

In the field of drug delivery, nanocarriers are submicron-sized (typically 1–1000 nm) colloidal systems designed to transport therapeutic agents. Their primary function within the context of controlled release is to enhance drug bioavailability, provide sustained release kinetics, and enable spatiotemporally precise delivery to target tissues, thereby minimizing systemic side effects [22]. The major platforms—liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, lipid nanoparticles, and inorganic systems—each offer unique mechanisms for controlling drug release, navigating biological barriers, and responding to specific physiological or external stimuli [23] [24]. This technical support center addresses the key experimental challenges and frequently asked questions researchers encounter when developing and characterizing these advanced drug delivery systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Liposomes

Q1: How can I improve the stability and circulation time of my liposomal formulations?

A: Short circulation half-life is often due to rapid clearance by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS). To mitigate this:

- PEGylation: Incorporate polyethylene glycol (PEG)-conjugated lipids (e.g., DSPE-PEG) during formulation. PEG creates a steric hydration layer on the liposome surface, reducing opsonization and recognition by immune cells, leading to a longer circulation half-life [20] [24]. Troubleshooting Tip: If your drug encapsulation efficiency drops after PEGylation, consider the post-insertion technique, where PEG-lipids are inserted into pre-formed drug-loaded liposomes.

- Optimize Lipid Composition: Use high-phase-transition-temperature lipids (e.g., DSPC) and include cholesterol (up to 45 mol%) to enhance bilayer rigidity and reduce drug leakage during storage and circulation [23].

Q2: My liposomes are leaking the encapsulated hydrophilic drug too quickly. What could be the cause?

A: Premature leakage can stem from several formulation and handling issues:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Bilayer Rigidity. A fluid lipid bilayer at physiological temperature allows for faster drug diffusion. Solution: Increase the cholesterol content or switch to phospholipids with longer, saturated acyl chains (e.g., replace DOPC with DSPC) to solidify the membrane [23].

- Cause 2: Osmotic Imbalance. A significant difference in osmolarity between the internal and external aqueous phases can cause swelling or shrinkage, stressing the membrane. Solution: Ensure the hydration buffer and the external suspension medium are iso-osmotic.

- Cause 3: Aggregation/Fusion. Liposome aggregation can compromise membrane integrity. Solution: Ensure a sufficient surface charge (high zeta potential, typically |±30| mV) through charged lipids and store formulations at 4°C under an inert gas.

Polymeric Nanoparticles

Q1: What are the key factors controlling drug release kinetics from polymeric nanoparticles?

A: Release kinetics are governed by a combination of diffusion, degradation, and swelling [20].

- Diffusion-Controlled Release: Initially, drug molecules close to the nanoparticle surface diffuse out rapidly (burst release). Sustained release follows as drug from the core diffuses through the polymer matrix. The polymer's porosity and hydrophobicity are critical factors [20].

- Erosion-/Degradation-Controlled Release: For biodegradable polymers like PLGA, the release rate is coupled to the hydrolysis rate of the polymer chains. This rate can be tuned by the lactide:glycolide ratio, molecular weight, and end-group chemistry. Crystalline polymers degrade more slowly than amorphous ones [20].

- Stimuli-Responsive Release: Incorporate monomers that respond to specific triggers (e.g., pH-sensitive linkers for acidic tumor microenvironments, or light-cleavable bonds) for precise spatial and temporal control [25].

Q2: I am observing a high initial burst release from my PLGA nanoparticles. How can I achieve a more linear release profile?

A: A high burst release indicates a large fraction of the drug is adsorbed or loosely associated near the particle surface.

- Optimize Fabrication Method: If using single emulsion, switch to double emulsion (w/o/w) for hydrophilic drugs to better encapsulate them within the core. For nanoprecipitation, try increasing the polymer concentration or adding a co-solvent to slow down diffusion and produce a denser matrix.

- Adjust Polymer Properties: Use a higher molecular weight PLGA or a more hydrophobic variant (higher lactide content) to slow down water penetration and drug diffusion.

- Surface Cross-linking/Washing: A brief, gentle cross-linking step or a more rigorous washing protocol after synthesis can remove the surface-associated drug, mitigating the burst effect.

Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs & NLCs)

Q1: When should I choose Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) over Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs)?

A: The choice depends on the drug's physicochemical properties and the desired release profile.

- Choose SLNs when a sustained release profile over several weeks is desired. They are composed of a solid lipid matrix that provides a slower, more controlled release. They are generally simpler to formulate and have high biocompatibility [23].

- Choose NLCs when encapsulating a high loading of a poorly soluble drug. By blending solid lipids with liquid lipids (oils), NLCs create a less ordered, imperfect crystal structure that provides more space for drug accommodation and reduces the risk of drug expulsion during storage [23]. They often offer a better compromise between loading capacity and release modulation.

Q2: My Solid Lipid Nanoparticle formulation is expelling the drug during storage. What is happening?

A: Drug expulsion is a classic challenge with SLNs and is typically caused by lipid polymorphism.

- Cause: After production, the lipid matrix often exists in a meta-stable, high-energy α-polymorph. Over time, it recrystallizes into a more stable, perfect β-polymorph with a highly ordered structure. This process squeezes out the encapsulated drug molecules, leading to expulsion and potential crystal growth [23].

- Solution:

- Use NLCs: The inclusion of liquid lipids impedes the formation of a perfect crystal lattice, dramatically improving physical stability and drug retention.

- Lipid Selection: Choose lipids that are less prone to polymorphic transitions (e.g., triglycerides that form stable β' crystals).

- Add Stabilizers: Incorporate certain surfactants (e.g., Poloxamer 188) or oils that can act as crystal inhibitors.

Inorganic Nanoparticles

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) for drug delivery?

A: MSNs are prized for their unique structural properties that enable precise controlled release:

- High Surface Area and Pore Volume: Allows for exceptionally high drug loading capacities [25].

- Tunable Pore Size: Pore diameter can be precisely controlled during synthesis (typically 2–10 nm), enabling size-based selection of drug molecules and modulation of diffusion rates.

- Easily Functionalizable Surface: The silanol-rich surface allows for simple grafting of "gatekeepers" or "nanovalves" (e.g., azobenzene, cyclodextrins) that can be triggered to open by stimuli like light, pH, or enzymes, providing exquisite control over release timing [25].

Q2: How can I confer biodegradability and reduce the toxicity of my inorganic nanoparticle formulation?

A: The perceived poor biodegradability of inorganic NPs is a major safety concern.

- Surface Coating/Functionalization: Biocompatible coatings like PEG, lipids, or chitosan can reduce non-specific interactions and shield the core from rapid dissolution, mitigating acute toxicity [26] [24].

- Size and Morphology Control: Smaller nanoparticles with high surface area may dissolve more readily. Designing nanoparticles with a specific size and porosity can facilitate their clearance from the body.

- Material Selection: Consider using biodegradable porous silicon or calcium phosphate nanoparticles as alternatives to silica or gold for certain applications, as they can dissolve into benign byproducts.

Essential Characterization Techniques: A Troubleshooting Guide

A systematic characterization protocol is non-negotiable for successful nanocarrier development. The table below summarizes key techniques, their purposes, and common issues encountered.

Table 1: Essential Characterization Techniques for Nanocarriers

| Parameter | Key Technique(s) | Purpose in Controlled Release | Common Issues & Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size & PDI | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [6] | Predicts biodistribution, cellular uptake, and release kinetics. | Issue: High PDI (>0.3). Solution: Optimize synthesis (e.g., mixing speed, solvent diffusion rate) or use a fractionation step like AF4 [6]. |

| Surface Charge | Zeta Potential [6] | Indicates colloidal stability and predicts interaction with biological membranes. | Issue: Low zeta potential leads to aggregation. Solution: Modify with charged lipids or polymers. Note: Sample dilution for measurement can alter results [6]. |

| Morphology | TEM, SEM [6] | Visualizes core-shell structure, lamellarity (liposomes), and pore structure. Confirms DLS data. | Issue: Sample preparation artifacts (e.g., deformation, aggregation on grid). Solution: Use cryo-TEM for liposomes and soft polymeric NPs. |

| Drug Release | Dialysis Bag, Franz Cell | Quantifies release kinetics (e.g., zero-order, first-order) under sink conditions. | Issue: Sink condition violation. Solution: Ensure sufficient volume and agitation of release medium. Issue: Membrane adsorption. Solution: Include controls and use appropriate membrane molecular weight cutoff. |

| Stability | Size & Zeta Tracking over Time | Assesses physical stability (aggregation, drug leakage) under storage conditions. | Issue: Particle growth over time. Solution: Improve surface charge, add steric stabilizers (PEG), or change storage temperature/buffer. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and their functions for developing controlled-release nanocarriers.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Nanocarrier Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Controlled Release |

|---|---|---|

| Lipids (for Liposomes/LNPs) | DSPC, Cholesterol, DSPE-PEG [23] [24] | Forms bilayer structure (DSPC), enhances rigidity and retention (Cholesterol), provides "stealth" properties (DSPE-PEG). |

| Polymers (for Polymeric NPs) | PLGA, PLA, PEG-PLGA block copolymers [20] | Forms biodegradable nanoparticle matrix for sustained release (PLGA/PLA). PEG block creates steric stabilization for long circulation. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Materials | Azobenzene (AZO), Spiropyran (SP) [25] | Acts as a light-responsive "gatekeeper" or trigger for spatiotemporally controlled drug release via photoisomerization. |

| Surface Targeting Ligands | Folate, Transferrin, Peptides, Antibodies [20] [24] | Enables active targeting by binding to receptors overexpressed on specific cell types (e.g., cancer cells), enhancing site-specific delivery. |

| Lipids for mRNA Delivery | Ionizable Cationic Lipids, PEG-lipids [26] | Ionizable lipids encapsulate and protect nucleic acids; PEG-lipids control particle size and stability during formulation. |

Experimental Protocols for Controlled Release Studies

Standard Protocol: In Vitro Drug Release Kinetics

Objective: To quantify the rate and extent of drug release from nanocarriers under simulated physiological conditions.

Materials:

- Drug-loaded nanocarrier dispersion

- Release medium (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4, with 0.1% w/v Tween 80 to maintain sink conditions)

- Dialysis tubing (appropriate MWCO) or a membrane-based dissolution apparatus

- Thermostated water bath/shaker

- HPLC or UV-Vis spectrophotometer for drug quantification

Method:

- Preparation: Place a precise volume of nanocarrier dispersion (with known total drug content) into a dialysis bag and seal it securely.

- Incubation: Immerse the dialysis bag in a large volume (typically 50-100x the sample volume) of pre-warmed release medium (37°C) under constant, gentle agitation.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals, withdraw a known aliquot of the external release medium for analysis. Immediately replace with an equal volume of fresh, pre-warmed medium to maintain sink conditions.

- Analysis: Quantify the drug concentration in each sample using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC).

- Data Modeling: Calculate the cumulative percentage of drug released and plot it against time. Fit the data to mathematical models (e.g., Korsmeyer-Peppas, Higuchi, zero-order) to elucidate the dominant release mechanism [20].

Advanced Protocol: Light-Triggered Drug Release

Objective: To demonstrate spatiotemporally controlled drug release from photosensitive nanocarriers using light irradiation.

Materials:

- Photosensitive nanocarriers (e.g., AZO-modified liposomes or MSNs) [25]

- Light source (LED or laser) at specific wavelength (e.g., UV ~360 nm for AZO trans-to-cis)

- In vitro release setup (as in Protocol 5.1)

- Power meter

Method:

- Baseline Release: Follow Steps 1-2 from Protocol 5.1. Monitor drug release for a baseline period without light irradiation.

- Light Trigger: After the baseline period, expose the entire dialysis bag or a specific segment to the light source at a controlled power density and for a set duration.

- Post-Irradiation Monitoring: Continue sampling the release medium as before, monitoring for a spike in release rate corresponding to the light trigger.

- Control: Run a parallel experiment with identical nanocarriers kept in the dark throughout the study.

- Analysis: Compare the release profiles of the light-exposed and dark-control samples to quantify the efficiency of the light-triggered release.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Mechanisms of Controlled Drug Release from Nanocarriers

Workflow for Nanocarrier Development & Characterization

Engineering Controlled Release: Advanced Materials, Formulation Techniques, and Targeting Strategies

This technical support center is designed within the context of a broader thesis on controlled drug release in nanocarriers. It addresses common experimental challenges faced by researchers when selecting and working with biodegradable polymers and lipids. The guidance below synthesizes current literature to provide troubleshooting and detailed methodologies to enhance the reproducibility and efficacy of your nanocarrier systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

Q1: How does the choice between a natural or synthetic biodegradable polymer influence the drug release profile from my nanocarrier?

The core distinction lies in the degradation mechanism, which directly controls the drug release kinetics.

- Synthetic Polymers (e.g., PLGA, PLA, PCL): These typically degrade via hydrolytic degradation, where water penetrates the matrix and cleaves ester bonds in the polymer backbone [27]. The rate is tunable by adjusting polymer composition (e.g., lactic to glycolic acid ratio in PLGA), molecular weight, and crystallinity. This allows for highly predictable, sustained release profiles over weeks to months.

- Natural Polymers (e.g., Chitosan, Alginate, Gelatin): These primarily degrade through enzymatic degradation by specific enzymes (e.g., proteases, lysozymes) [27]. This process is highly specific but can be less predictable as it depends on the local enzymatic environment at the target site, leading to potential variations in release rates.

Q2: What are the key formulation challenges for lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) in RNA delivery, and how can they be addressed computationally?

LNP optimization is plagued by a vast design space and limited a priori design principles. Key challenges include achieving efficient endosomal escape and maintaining colloidal stability [28].

- Challenge 1: Environment-Dependent Protonation of Ionizable Lipids. The protonation state of ionizable lipids, critical for endosomal escape, is environment-dependent (pH, lipid packing) and difficult to characterize experimentally [28].

- Computational Solution: Use constant pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) simulations. A scalable CpHMD model has been shown to accurately reproduce the apparent pKa values of different LNP formulations, providing molecular-level insight into charge states under different biological conditions [28].

- Challenge 2: Understanding Self-Assembly and Structure. The complex process of LNP formation and its final nanostructure are difficult to observe.

- Computational Solution: Employ Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics (CG-MD) simulations. CG-MD allows for the modeling of larger systems over longer timescales to reveal detailed molecular structures and self-assembly mechanisms of LNPs, which are often difficult to characterize experimentally [28].

Q3: My microsphere formulation has inconsistent drug release profiles between batches. What are the most critical factors to control?

Inconsistent release is often a function of poor control over microsphere architecture and manufacturing.

- Critical Factor 1: Particle Size and Distribution. Drug release kinetics are highly dependent on surface area and diffusion paths. Ensure tight control over emulsification and homogenization processes during synthesis to achieve a uniform particle size distribution [29].

- Critical Factor 2: Drug-Polymer Interactions and Loading Method. The interaction between the drug and the polymer matrix (e.g., hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance) significantly impacts encapsulation efficiency and release. Optimize the drug loading strategy (encapsulation vs. adsorption) and analyze potential chemical interactions [29].

- Critical Factor 3: Polymer Crystallinity and Molecular Weight. These intrinsic polymer properties directly govern the rate of water ingress and polymer chain cleavage, thereby controlling the degradation and release rate. Use polymers with consistent specifications [27] [29].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid, burst release of drug from nanoparticles. | Poor encapsulation; drug adsorbed on the surface rather than trapped within the matrix. | Optimize synthesis (e.g., double emulsion for hydrophilic drugs); increase polymer molecular weight; add a surface wash step to remove unencapsulated drug [27]. | ||

| Incomplete drug release from polymer matrix. | Drug degradation during encapsulation; overly stable polymer matrix; hydrophobic interactions trapping the drug. | Use more gentle encapsulation methods (e.g., avoid high-shear sonication); select a polymer with a faster degradation rate (e.g., PLGA 50:50 over PLA); modify the polymer with hydrophilic segments [27] [29]. | ||

| Low encapsulation efficiency (EE) in LNPs. | Incorrect lipid-to-cargo ratio; poor mixing during formation; cargo properties (size, charge). | Systemically vary the nitrogen-to-phosphate (N/P) ratio for nucleic acids; use microfluidics for highly reproducible mixing; explore helper lipids that improve cargo complexation [28] [30]. | ||

| Poor colloidal stability of nanocarriers (aggregation). | Inadequate surface charge (zeta potential); insufficient steric stabilization; unstable lipid mixture. | Incorporate a small percentage (1-5 mol%) of PEG-lipids or PEG-polymers to provide steric stabilization [31] [30]. Optimize surface charge, as a highly positive or negative zeta potential (typically > | ±30 | mV) improves electrostatic stability [30]. |

| High cytotoxicity of lipid-based carriers. | Cationic lipid components disrupting cell membranes; non-biodegradable polymer accumulation. | Shift to ionizable lipids that are neutral at physiological pH but positively charged in acidic endosomes. Use biodegradable lipids (e.g., containing ester bonds) or polymers (e.g., PLGA) that break down into non-toxic metabolites [31] [27]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computational Screening of Ionizable Lipids Using CpHMD

This methodology allows for in silico prediction of a critical performance property (pKa) before synthesis [28].

System Setup:

- Software: Use a molecular dynamics package with CpHMD capabilities (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD).

- Model Building: Construct a model membrane patch containing the ionizable lipid, phospholipids (e.g., DOPE), cholesterol, and PEG-lipid at desired molar ratios.

- Parameterization: Employ a force field (e.g., CHARMM, Martini) with parameters for the protonated and deprotonated states of the ionizable lipid's titratable group.

Simulation Execution:

- Solvate the system in a saline buffer box.

- Run CpHMD simulations at a range of pH values (e.g., from 4.5 to 7.4) to model the different environments from bloodstream to endosome.

- Utilize a scalable CpHMD method, such as λ-dynamics, which performs at speeds comparable to standard MD [28].

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the fractional protonation of the ionizable lipid as a function of pH.

- Fit the data to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation to determine the apparent pKa value of the lipid within the LNP membrane context.

- Validate the model by comparing computed pKa values with experimental measurements for a set of reference lipids (target MAE < 0.5 pKa units) [28].

Protocol 2: Formulating and Characterizing Drug-Loaded PLGA Microspheres

A standard method for creating a classic biodegradable polymer controlled-release system [27] [29].

Formulation (Single Emulsion - O/W Method):

- Dissolve the drug and PLGA polymer in a volatile organic solvent (e.g., dichloromethane).

- Emulsify this organic phase into a large volume of an aqueous surfactant solution (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol, PVA) using a high-speed homogenizer to form an oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion.

- Stir the emulsion continuously for several hours to evaporate the organic solvent, hardening the microspheres.

- Collect the microspheres by centrifugation, wash repeatedly with water to remove residual solvent and surfactant, and lyophilize.

Critical Characterization:

- Particle Size & Distribution: Use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). Aim for a low PDI (<0.2) for a narrow distribution.

- Surface Morphology: Analyze by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

- Drug Encapsulation Efficiency (EE): Dissolve a known amount of microspheres in a suitable solvent and measure drug concentration via HPLC or UV-Vis. EE% = (Actual Drug Load / Theoretical Drug Load) * 100.

- In Vitro Drug Release:

- Place a known amount of drug-loaded microspheres in a phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at 37°C under gentle agitation.

- At predetermined time points, centrifuge the samples and collect the release medium for drug quantification, replacing with fresh buffer to maintain sink conditions.

- Plot the cumulative drug release over time to establish the release profile.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

| Category | Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Polymers | PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | The most widely used biodegradable polymer; degradation rate and drug release profile can be finely tuned by adjusting the lactide:glycolide ratio [27]. |

| PCL (Polycaprolactone) | A semi-crystalline polyester with a slower degradation rate, suitable for long-term (several months) drug delivery applications [27]. | |

| Natural Polymers | Chitosan | A natural polysaccharide derived from chitin; known for its mucoadhesive properties and ability to enhance penetration across biological barriers [27]. |

| Alginate | A polysaccharide that can form gentle hydrogels in the presence of divalent cations (e.g., Ca²⁺), ideal for encapsulating sensitive biomolecules [27]. | |

| Lipid Components | Ionizable Lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA) | The functional core of modern LNPs; positively charged at low endosomal pH to facilitate membrane disruption and RNA release, but neutral in the bloodstream to reduce toxicity [28] [31]. |

| Helper Lipids (e.g., DOPE) | Phospholipids that promote non-bilayer structures and facilitate endosomal escape by supporting the transition to a hexagonal phase [30]. | |

| PEG-Lipids | Polyethylene glycol-conjugated lipids used to form the surface corona of LNPs; provide colloidal stability, reduce protein adsorption, and control particle size during formulation [31]. | |

| Cholesterol | A structural lipid that integrates into LNP bilayers to enhance stability and integrity, mimicking its role in natural cell membranes [30]. | |

| Characterization Tools | Constant pH MD (CpHMD) | A computational model to accurately simulate the environment-dependent protonation states of ionizable lipids in LNPs, enabling rational design [28]. |

| Coarse-Grained MD (CG-MD) | A simulation approach that groups atoms into beads, allowing for the study of LNP self-assembly and structure over longer timescales than all-atom MD [28]. |

Visualizing the Degradation Pathways of Biodegradable Polymers

The primary mechanisms by which biodegradable polymers break down to release their drug cargo are illustrated below.

Troubleshooting Guides

Microfluidics Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Channel Clogging | Particle aggregation, precipitation at interface, too high polymer concentration [32] | Reduce PLGA concentration in organic phase; increase total flow rate (TFR) to enhance shear; use co-solvents to prevent rapid precipitation [32] |

| High Polydispersity Index (PDI) | Inefficient mixing, non-uniform flow profiles, fluctuating flow rates [32] | Use micromixer with chaotic advection (e.g., herringbone); increase TFR to turbulent regime; optimize Flow Rate Ratio (FRR); use 3-inlet design for focused mixing [32] |

| Irreproducible Particle Size Between Batches | Manual pressure control, flow rate instability, chip surface fouling [32] | Use syringe pumps with high precision; implement pulse-dampeners; standardize chip cleaning protocol (e.g., NaOH rinse); use CFD modeling to validate consistent mixing [32] |

| Low Drug Loading Efficiency | Rapid mixing causing drug expulsion, poor drug-polymer compatibility, drug too hydrophilic [20] | Optimize FRR to moderate nucleation kinetics; modify polymer chemistry (e.g., use PLGA with compatible end-groups); use lipophilic drug analogs if possible [20] |

Nanoprecipitation Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|