Inorganic vs. Organic Nanosystems: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of inorganic and organic nanosystems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Inorganic vs. Organic Nanosystems: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of inorganic and organic nanosystems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles, distinct physicochemical properties, and unique advantages of each system. The scope extends to synthesis methodologies, advanced biomedical applications in drug delivery, theranostics, and biosensing, alongside a critical evaluation of challenges including toxicity, biocompatibility, and scalability. By integrating troubleshooting strategies, optimization techniques, and validation benchmarks, this analysis aims to guide the selection, development, and clinical translation of nanotechnologies, offering actionable insights for the future of nanomedicine.

Defining the Landscape: Core Principles and Properties of Organic and Inorganic Nanosystems

Comparative Analysis of Organic and Inorganic Nanosystems

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Organic and Inorganic Nanosystems

| Feature | Organic Nanosystems | Inorganic Nanosystems |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Composition | Carbon-based polymers (e.g., chitosan, PLA), lipids, proteins [1] | Metals (e.g., Au, Ag, Fe), metal oxides (e.g., ZnO, Fe₃O₄, TiO₂) [1] |

| Structural Examples | Micelles, dendrimers, liposomes, nanogels, polymeric NPs [1] | Metal nanoparticles, metal oxide nanostructures, quantum dots [1] |

| Biocompatibility | Generally high, biodegradable, and non-toxic [1] | Variable; can be non-toxic and biocompatible (e.g., ZnO, Fe₃O₄), but some may pose toxicity concerns (e.g., Co, Cd) [1] |

| Stability | Moderate; can be sensitive to light and heat [1] | High; superior chemical and physical stability [1] |

| Drug Loading | High encapsulation efficiency for hydrophilic/hydrophobic drugs [2] | Often requires surface functionalization for effective drug loading [2] |

| Targeting Ability | Can be functionalized with ligands for active targeting [2] | Surface can be modified with antibodies, peptides, DNA for targeted delivery [1] |

| Key Advantages | Biodegradable, tunable drug release kinetics, versatile synthesis [1] | Unique optoelectrical properties (e.g., plasmon resonance), high catalytic activity, magnetic properties (e.g., Fe₃O₄) [1] |

| Primary Biomedical Applications | Drug and vaccine delivery, tissue engineering, gene therapy [2] [1] | Drug delivery, bioimaging, biosensors, photothermal therapy, antibacterial agents [2] [1] |

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Experimental Drug Delivery

| Parameter | Organic Nanosystems (Liposomes/Polymers) | Inorganic Nanosystems (Gold/Mesoporous Silica) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Drug Loading Capacity | High (5-30% w/w) | Moderate to High (1-20% w/w) |

| Controlled Release Profile | Sustained release (days to weeks) via polymer degradation [2] | Stimuli-responsive release (e.g., pH, light, magnetic field) [1] |

| Cellular Uptake Efficiency | High, especially with surface charge modification | High, enhanced by functionalization (e.g., with PEG, targeting ligands) [1] |

| Blood Circulation Half-life | Long (hours to days) with PEGylation | Variable; can be prolonged with appropriate coating [1] |

| In Vivo Toxicity Profile | Generally low, metabolized into benign products [1] | Requires careful evaluation; potential for ion leakage and long-term accumulation [1] |

| Anticancer Efficacy (Model Study) | Significant tumor growth inhibition | Enhanced cytotoxicity under specific stimuli (e.g., laser-induced hyperthermia) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Evaluations

Protocol: Synthesis of Chitosan-Based Organic Nanoparticles

This protocol describes the ionotropic gelation method for creating polymeric nanoparticles [2].

- Principle: Nanoparticles are formed by coacervation induced by the electrostatic interaction between a positively charged polymer (chitosan) and a polyanion (sodium tripolyphosphate - TPP) [2].

- Materials:

- Chitosan (low molecular weight)

- Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP)

- Acetic acid solution (1% v/v)

- Magnetic stirrer

- Syringe pump or micropipette

- Procedure:

- Dissolve chitosan in 1% acetic acid solution to a final concentration of 1-2 mg/mL under magnetic stirring until clear.

- Prepare an aqueous TPP solution at a concentration of 0.5-1.0 mg/mL.

- Add the TPP solution dropwise (e.g., at 0.5 mL/min) into the chitosan solution under constant stirring.

- Continue stirring for 60 minutes to allow for nanoparticle formation and hardening.

- Purify the nanoparticle suspension by centrifugation (e.g., 15,000 rpm, 30 minutes) and re-suspend in deionized water or buffer.

- Characterization: Particle size and zeta potential are measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS). Morphology is confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Protocol: Anti-Aging Activity Assessment via MMP-1 Inhibition

This assay evaluates the potential of nanoparticles, such as Gallic Acid-coated Gold Nanoparticles (GA-AuNPs), to mitigate skin aging by inhibiting MMP-1 expression [2].

- Principle: In a hyperglycemic environment, matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) degrades the extracellular matrix (ECM), accelerating skin aging. Effective anti-aging compounds can suppress high-glucose-mediated MMP-1 induction [2].

- Materials:

- Human dermal fibroblast (HDF) cell line

- High-glucose culture medium

- Test nanoparticles (e.g., GA-AuNPs)

- UVA irradiation source (for some experimental setups)

- ELISA kit for human MMP-1

- Western blot apparatus

- Procedure:

- Culture HDF cells in high-glucose medium to simulate an aging-prone environment.

- Pre-treat cells with varying concentrations of the test nanoparticles (e.g., GA-AuNPs) for a set period (e.g., 4 hours).

- For photo-aging models, expose cells to a controlled dose of UVA radiation.

- Incubate the cells for 24-48 hours.

- Collect the cell culture supernatant.

- Quantify the secreted MMP-1 protein levels using an ELISA kit, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- Data Analysis: Compare MMP-1 levels in treated groups against the untreated control (high-glucose only). A significant reduction in MMP-1 indicates anti-aging potential.

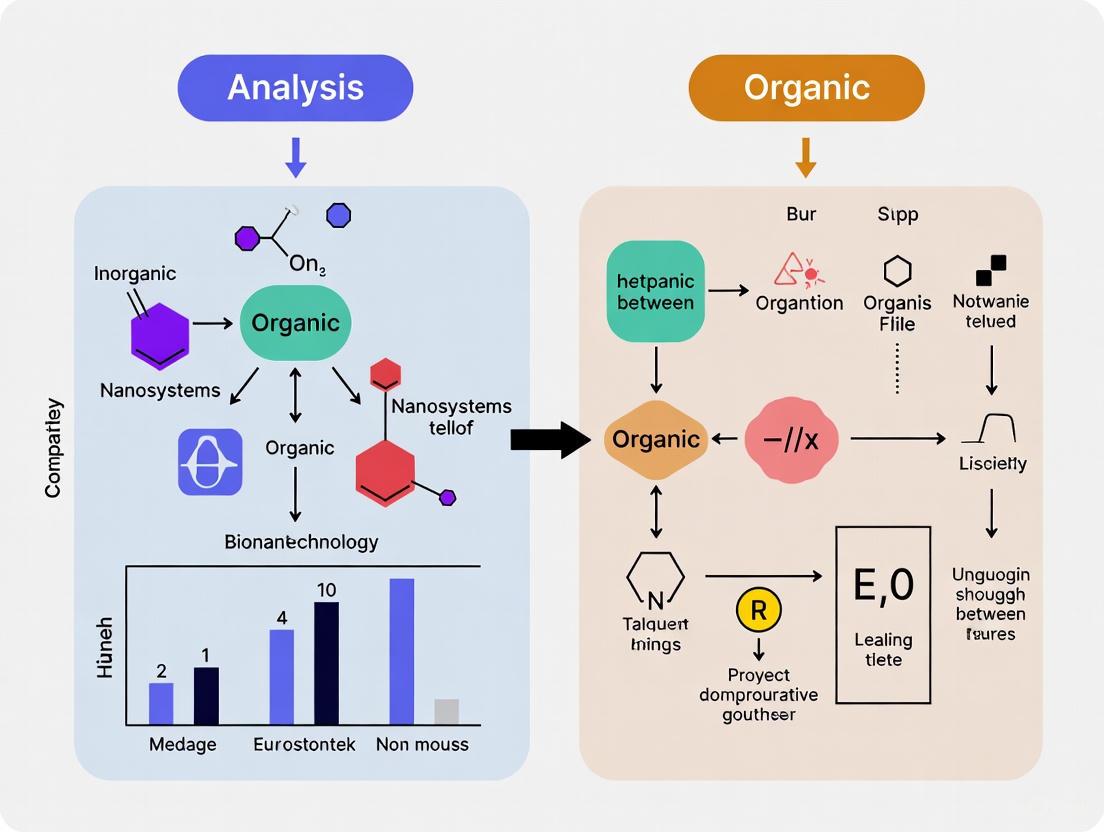

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Skin Aging Pathway

Nano Drug Synthesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Nano-Biomedical Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Chitosan | A natural polymer used to form biodegradable nanoparticles via ionotropic gelation for drug encapsulation and delivery [2]. |

| Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | A cross-linking agent used to ionically gel cationic polymers like chitosan, facilitating nanoparticle formation [2]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A polymer used to functionalize the surface of nanoparticles to improve their stability, reduce opsonization, and prolong blood circulation time [1]. |

| Gallic Acid | A natural polyphenol that can be coated onto gold nanoparticles (GA-AuNPs) to confer anti-aging properties by inhibiting ECM degradation [2]. |

| Folate (Vitamin B9) | Used to functionalize nanocarriers to target the Folate Receptor 1 (FOLR1), which is overexpressed on many cancer cells, enabling targeted drug delivery [2]. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanoparticles | A semiconducting metal oxide nanomaterial used in biomedical applications such as biosensors, drug delivery, and for its antibacterial properties [1]. |

| Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (e.g., Fe₃O₄) | Magnetic nanoparticles used for targeted drug delivery (guided by an external magnetic field), magnetic hyperthermia cancer therapy, and as MRI contrast agents [1]. |

| Curcumin | A neuroprotective phytochemical that can be loaded into nanocarriers to enhance its bioavailability and stability for potential treatment of CNS disorders like Alzheimer's disease [2]. |

| Dendrimers | Highly branched, synthetic polymeric nanoparticles with a well-defined structure, used as carriers for drugs and genes due to their tunable surface functionality [1]. |

| Liposomes | Spherical vesicles with a phospholipid bilayer, mimicking cell membranes, widely used to encapsulate and deliver both hydrophilic and hydrophobic therapeutic agents [1]. |

The development of drug delivery systems represents a critical frontier in modern therapeutics, with nanoparticle technology emerging as a transformative platform for addressing fundamental challenges in medicine. Traditional drug delivery methods, including oral and parenteral administration, face significant limitations such as poor bioavailability, gastrointestinal irritation, first-pass metabolism, non-specific distribution, and systemic toxicity [3]. These challenges have driven the scientific community toward nanoscale solutions that can enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Within this landscape, a fundamental division has emerged between two broad categories of nanocarriers: organic nanosystems derived from biological or synthetic organic molecules, and inorganic nanosystems typically composed of metallic, ceramic, or other non-organic materials [4].

The core thesis of this comparative analysis posits that organic nanosystems—specifically biopolymers, lipids, and dendrimers—offer superior biocompatibility profiles while maintaining effective drug delivery capabilities compared to their inorganic counterparts. Biocompatibility, defined as the ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application, is a critical determinant of clinical viability for nanomedicine [5]. This parameter encompasses not only the absence of toxicity, allergic potential, and immunogenicity but also favorable interactions with cells, tissues, and the immune system [6]. As the field progresses toward increasingly sophisticated therapeutic applications, the inherent safety and biocompatibility of delivery platforms become paramount considerations alongside their functional efficacy.

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of organic and inorganic nanosystems, with particular emphasis on experimental data validating the enhanced biocompatibility of organic platforms. Through systematic evaluation of synthesis methodologies, physicochemical characterization, biological performance metrics, and therapeutic outcomes, we aim to establish an evidence-based framework for selecting nanocarrier systems based on their intended application and biocompatibility requirements.

Organic Nanosystems: Structures, Properties, and Applications

Classification and Fundamental Characteristics

Organic nanosystems represent a diverse class of nanocarriers derived from biological or synthetic organic molecules, characterized by their carbon-based molecular frameworks and typically superior biological compatibility. These systems are broadly categorized into three principal classes: biopolymers, lipid-based systems, and dendrimers, each possessing distinct structural attributes and functional capabilities [3].

Biopolymers include natural macromolecules such as polysaccharides (chitosan, cellulose, alginate) and proteins (albumin, silk fibroin, collagen). These materials exhibit inherent biocompatibility due to their structural similarity to biological components and predictable biodegradation pathways [7]. Their practical application, particularly in load-bearing biomedical contexts, is sometimes limited by relatively low mechanical strength, which often necessitates blending with synthetic polymers or reinforcement with inorganic substances to enhance their functional properties [7].

Lipid-based nanosystems encompass a range of structures including liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, and nanostructured lipid carriers. These systems excel at encapsulating both hydrophilic and hydrophobic therapeutic agents and demonstrate particularly favorable safety profiles due to their compositional similarity to biological membranes [3].

Dendrimers are highly branched, synthetically produced macromolecules with well-defined architectures and monodisperse characteristics. Their unique tree-like branching structure provides numerous surface functional groups for drug conjugation or modification, enabling precise control over drug loading and release kinetics [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Major Organic Nanosystems

| Nanosystem Type | Representative Materials | Structural Features | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biopolymers | Chitosan, Alginate, Collagen, Silk Fibroin | Natural macromolecular chains, often with repeating monomer units | Innate biocompatibility, biodegradability, structural similarity to ECM |

| Lipid-Based Systems | Phospholipids, Triglycerides, Fatty Acids | Vesicular or solid matrix structures | Excellent drug encapsulation, biological membrane similarity, versatility |

| Dendrimers | PAMAM, PPI | Highly branched, tree-like architecture with core, branches, and surface groups | Monodispersity, controllable multivalency, well-defined drug conjugation sites |

Synthesis and Functionalization Methodologies

The synthesis of organic nanosystems employs diverse methodologies tailored to their specific chemical nature and intended application. Biopolymer nanoparticles are frequently produced using techniques such as nano-precipitation, ionic gelation, and emulsification-solvent evaporation [8] [7]. For instance, polylactic acid (PLA) nanoparticles can be synthesized using the nano-precipitation method, wherein the polymer is dissolved in an organic solvent (e.g., dichloromethane) followed by addition to an aqueous phase under moderate stirring, resulting in the formation of homogeneous, spherical nanoparticles [8].

Lipid-based nanosystems are typically produced through methods such as high-pressure homogenization, solvent evaporation, and microemulsion techniques. These approaches enable control over critical parameters including particle size, polydispersity, and drug loading capacity [3].

Dendrimer synthesis employs iterative stepwise reactions such as divergent or convergent approaches, building the branched architecture layer by layer (generation). This controlled synthesis allows precise engineering of molecular weight, size, and surface functionality [3].

Surface functionalization represents a crucial strategy for enhancing the performance of organic nanosystems. Ligand conjugation using targeting moieties (e.g., antibodies, peptides, aptamers) enables specific recognition of cellular biomarkers, while PEGylation—the attachment of polyethylene glycol chains—imparts "stealth" properties by reducing opsonization and extending systemic circulation half-life [7] [3]. Recent advances have also focused on stimuli-responsive designs that release therapeutic payloads in response to specific physiological triggers such as pH changes, enzyme activity, or redox gradients [3].

Inorganic Nanosystems: Contrasting Properties and Applications

Classification and Fundamental Characteristics

Inorganic nanosystems comprise a broad category of nanocarriers derived from non-carbon-based materials, including metals, metal oxides, semiconductors, and ceramics. These systems exhibit unique physicochemical properties distinct from their organic counterparts, often leveraging characteristics such as magnetic responsiveness, plasmonic effects, and fluorescence for diagnostic and therapeutic applications [4].

Metallic nanoparticles, particularly those composed of noble metals such as gold and silver, exhibit surface plasmon resonance—a collective oscillation of conduction electrons in response to specific wavelengths of light. This property enables applications in photothermal therapy, bioimaging, and sensing [9] [10]. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) with an average size of 28.3 nanometers, for instance, have demonstrated effectiveness in treating breast cancer cells by inhibiting interleukin-6 production through specific molecular pathways [9].

Metal oxide nanoparticles include materials such as iron oxide (Fe₃O₄, γ-Fe₂O₃), zinc oxide (ZnO), and titanium dioxide (TiO₂). Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) are particularly notable for their superparamagnetic properties when sized below 20 nm, enabling applications in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic hyperthermia treatment, and magnetically-guided drug delivery [4].

Ceramic nanoparticles consist of inorganic compounds such as silica (SiO₂), alumina (Al₂O₃), and hydroxyapatite (HA). These materials offer significant advantages including high stability against pH and temperature variations, tunable porosity, and protection of encapsulated molecules from denaturation [4]. Their composition similarity to natural bone minerals makes them particularly suitable for bone tissue engineering applications [11].

Quantum dots are semiconductor nanocrystals (e.g., CdSe, CdS) with size-tunable fluorescence properties, making them valuable as imaging probes and biosensors [10].

Table 2: Fundamental Characteristics of Major Inorganic Nanosystems

| Nanosystem Type | Representative Materials | Structural Features | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Nanoparticles | Gold, Silver, Iron | Crystalline metal cores with surface functionalization | Plasmonic properties, catalytic activity, conductivity |

| Metal Oxides | Iron Oxide, Zinc Oxide, Titanium Dioxide | Metal-oxygen crystalline lattices | Magnetic properties, photocatalytic activity, semiconductor behavior |

| Ceramic Nanoparticles | Silica, Alumina, Hydroxyapatite | Metal-nonmetal compositions with crystalline or amorphous structures | High stability, tunable porosity, biocompatibility in specific applications |

| Quantum Dots | CdSe, CdS, PbS | Semiconductor nanocrystals with quantum confinement effects | Size-tunable fluorescence, high brightness, photostability |

Synthesis and Functionalization Methodologies

Inorganic nanoparticle synthesis employs both "top-down" approaches (physical methods that break down bulk materials) and "bottom-up" approaches (chemical methods that build nanoparticles from molecular precursors) [4]. Gold nanoparticles are frequently synthesized using the seed-mediated growth approach, which enables precise control over size and shape [8]. Ceramic nanoparticles such as calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) can be produced using co-precipitation methods, while silica nanoparticles are typically synthesized via sol-gel techniques [8].

Surface functionalization of inorganic nanoparticles is essential for improving biocompatibility and targeting capability. Common strategies include coating with silica shells, polymers, or biomolecules to enhance colloidal stability and reduce toxicity [5] [4]. For instance, IONPs are often coated with polymers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) or dextran to improve their stability in physiological environments and reduce nonspecific protein adsorption [4]. The creation of hybrid organic-inorganic nanocomposites represents another significant advancement, combining the advantageous properties of both material classes while mitigating their individual limitations [9].

Direct Comparative Analysis: Experimental Evidence

Methodology for Comparative Studies

Rigorous comparative evaluation of nanosystem performance requires carefully controlled experimental conditions and standardized characterization methodologies. In one comprehensive study, researchers systematically evaluated the passive targeting capability of four types of inorganic and organic nanoparticles across three different tumor models [8]. The investigated systems included polylactic acid (PLA) nanoparticles representing organic polymeric systems, and gold (Au), calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), and silica (SiO₂) nanoparticles as inorganic counterparts.

The experimental protocol involved several critical stages. First, nanoparticle synthesis and characterization ensured consistent physicochemical properties: all nanoparticles were synthesized to demonstrate homogeneous size distributions and spherical morphology, with careful control of parameters such as size, surface charge, and morphology through techniques including transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [8]. Next, in in vivo distribution studies, nanoparticles were administered intravenously to tumor-bearing animal models, with subsequent analysis of biodistribution and tumor accumulation efficiency. Finally, quantitative assessment of targeting efficiency was performed using rigorous analytical methods to determine the percentage of injected dose accumulated in tumors and other major organs [8].

This systematic approach enabled direct comparison of targeting performance while controlling for variables such as administration route, dosage, and tumor model characteristics, providing robust experimental data for objective evaluation of organic versus inorganic nanosystems.

Biocompatibility and Toxicity Assessment

Biocompatibility assessment represents a critical component in the evaluation of nanosystems for biomedical applications. Comprehensive testing evaluates multiple aspects of biological response, including toxicity, allergic potential, immunogenicity, and long-term tissue compatibility [7] [5].

For organic nanosystems, biodegradation pathways and metabolic clearance mechanisms significantly influence biocompatibility. Biopolymers such as PLA undergo hydrolytic degradation through ester bond cleavage, with rate influenced by factors including temperature, humidity, and catalyst availability [7]. The degradation products are typically metabolic intermediates that enter normal biochemical pathways, minimizing potential for cumulative toxicity. However, some organic systems can provoke immune responses; for instance, PLA-based microspheres have been shown to induce inflammatory reactions in vivo, though this can be mitigated through modification with short-chain PEG to enhance histocompatibility [7].

For inorganic nanosystems, biocompatibility concerns include potential metal ion leaching, oxidative stress generation, and persistent accumulation in tissues. The size-dependent cellular uptake of inorganic nanoparticles can lead to intracellular accumulation and potential organelle damage [5] [4]. Surface modification strategies have been developed to address these concerns; for example, coating with biocompatible polymers or biomolecules can reduce cytotoxic effects and improve clearance profiles [5].

Table 3: Comparative Biocompatibility Assessment of Organic and Inorganic Nanosystems

| Parameter | Organic Nanosystems | Inorganic Nanosystems |

|---|---|---|

| Degradation Pathway | Enzymatic or hydrolytic cleavage to metabolic intermediates | Often slow dissolution or persistent structure |

| Clearance Mechanism | Renal clearance or metabolic assimilation | Reticuloendothelial system uptake, potential tissue accumulation |

| Inflammatory Potential | Generally low, but varies with material (e.g., PLA can be inflammatory) | Variable; metal ions can trigger oxidative stress and inflammation |

| Immunogenicity | Low for most biopolymers and lipids; PEG can induce antibodies | Variable; surface properties critically influence immune recognition |

| Long-term Toxicity Concerns | Minimal for FDA-approved materials | Potential for metal accumulation and chronic toxicity |

Tumor Targeting Efficiency and Therapeutic Performance

The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect plays a central role in passive tumor targeting, leveraging the characteristic features of tumor vasculature—including wide endothelial gaps, poor structural integrity, and impaired lymphatic drainage—to enable selective nanoparticle accumulation [8] [10]. Comparative studies have revealed significant differences in how organic and inorganic nanosystems exploit this phenomenon.

Experimental data from direct comparisons demonstrate that both organic and inorganic nanoparticles can accumulate in tumor tissue via the EPR effect, but with notable differences in efficiency and distribution patterns [8]. In one comprehensive study, researchers observed that tumor models significantly impacted the delivery efficiency of nanoparticles with different chemical structures but similar sizes, highlighting the importance of considering tumor heterogeneity when designing nanocarriers [8].

The surface characteristics of nanoparticles critically influence their tumor accumulation. Neutral zeta potential or potentials in the range of -10/+10 mV have been associated with higher delivery efficacy compared to strongly positive (>+10 mV) or negative (<-10 mV) surfaces [8]. This finding has important implications for both organic and inorganic systems, as surface charge can be modulated through appropriate functionalization strategies.

Diagram 1: Nanoparticle Tumor Targeting via EPR Effect

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Advanced research in nanosystem development requires specialized reagents and materials carefully selected for their specific functions in synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation. The following table summarizes essential research tools and their applications in the development and assessment of organic and inorganic nanosystems.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Nanosystem Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Biodegradable polymer matrix for nanoparticle formation | Organic nanosystem fabrication via nano-precipitation [8] |

| Chitosan | Natural polysaccharide for mucoadhesive nanoparticles | Drug delivery systems exploiting bioadhesion [7] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Surface functionalization for stealth properties | Reducing protein adsorption and extending circulation half-life [7] |

| Gold Chloride (HAuCl₄) | Precursor for gold nanoparticle synthesis | Seed-mediated growth of plasmonic nanoparticles [8] |

| Iron Chlorides (FeCl₂/FeCl₃) | Precursors for iron oxide nanoparticles | Co-precipitation synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles [4] |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Silicon source for silica nanoparticles | Sol-gel synthesis of ceramic nanoparticles [8] |

| Calcium Chloride & Sodium Carbonate | Precursors for calcium carbonate nanoparticles | Co-precipitation synthesis of pH-responsive nanoparticles [8] |

| Cell Culture Media & Assay Kits | In vitro biocompatibility assessment | Cytotoxicity, immunogenicity, and cellular uptake studies [5] |

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive characterization of nanosystems necessitates sophisticated analytical techniques to evaluate physicochemical properties and biological interactions. Key methodologies include:

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) provide high-resolution visualization of nanoparticle morphology, size, and distribution [8]. These techniques are essential for confirming structural attributes and detecting potential aggregation.

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) enables determination of hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution in suspension, while Zeta Potential Measurements assess surface charge, which correlates with colloidal stability and cellular interactions [8] [4].

Spectroscopic Techniques including UV-Vis spectroscopy (particularly for metallic nanoparticles exhibiting surface plasmon resonance), Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) for surface chemistry analysis, and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) for structural characterization provide complementary information about composition and functionalization [4] [10].

Thermal Analysis methods such as Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) offer insights into thermal stability, phase transitions, and composition, which are particularly relevant for polymer-based systems and applications requiring thermal processing or stability [7].

In vitro Biological Characterization encompasses a range of assays including cell viability studies (MTT, XTT, WST assays), cellular uptake quantification (flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy), and hemocompatibility assessment (hemolysis assays) [5]. These assays provide critical preliminary data on biocompatibility before advancing to more complex in vivo studies.

The comprehensive comparative analysis presented in this review substantiates the central thesis that organic nanosystems—including biopolymers, lipids, and dendrimers—offer distinct advantages in biocompatibility while maintaining effective drug delivery capability. The experimental evidence demonstrates that these systems generally exhibit favorable biodegradation profiles, low immunogenicity, and reduced long-term toxicity concerns compared to many inorganic counterparts. However, it is crucial to recognize that inorganic nanosystems provide unique functionalities—including magnetic responsiveness, plasmonic properties, and fluorescence—that enable applications difficult to achieve with purely organic platforms.

Future developments in nanomedicine will likely focus on several key areas. Hybrid organic-inorganic systems represent a promising direction, combining the advantageous properties of both material classes while mitigating their individual limitations [9]. Stimuli-responsive designs that release therapeutic payloads in response to specific pathological triggers (e.g., pH, enzyme activity, redox status) will enhance targeting precision and reduce off-target effects [3] [10]. Advanced manufacturing technologies including microfluidics and 3D printing will enable improved reproducibility and scalability of nanosystem production [12]. Finally, personalized medicine approaches will leverage nanoplatforms tailored to individual patient characteristics and disease profiles, potentially revolutionizing treatment paradigms for cancer and other complex disorders [3].

The optimal selection between organic and inorganic nanosystems ultimately depends on the specific therapeutic application, balancing factors including payload characteristics, targeting requirements, diagnostic needs, and safety considerations. As the field continues to evolve, evidence-based comparative assessments will play an increasingly important role in guiding the rational design of nanocarriers for enhanced therapeutic outcomes.

In the evolving landscape of nanotechnology, inorganic nanosystems have emerged as particularly powerful tools for biomedical applications, offering a distinct set of advantages that complement their organic counterparts. While organic nanoparticles (like liposomes and polymeric micelles) are prized for their biodegradability and low toxicity, inorganic nanoparticles (INPs) provide exceptional stability, tunable physicochemical characteristics, and unique intrinsic optical, magnetic, and catalytic properties that are often difficult to replicate with organic materials. [13] [14] These properties—including surface plasmon resonance (SPR) in metals, superparamagnetism in metal oxides, and size-tunable fluorescence in quantum dots—are not merely additive but are fundamentally derived from their inorganic composition and nanoscale dimensions. [15] [16] This guide provides a comparative analysis of three major classes of inorganic nanosystems—metal-based, metal oxide-based, and quantum dots—focusing on their distinctive properties, performance metrics in key applications, and the experimental methodologies that enable their use in advanced drug delivery, imaging, and therapeutic applications.

Comparative Analysis of Key Inorganic Nanosystems

The table below provides a structured comparison of the three primary categories of inorganic nanosystems, highlighting their defining characteristics, unique properties, and primary applications.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Inorganic Nanosystems for Biomedical Applications

| Nanoparticle Type | Core Composition Examples | Unique Optical/Magnetic Properties | Key Advantages for Biomedicine | Primary Application Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-Based | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), Platinum (Pt) [15] | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Superparamagnetism, Strong X-ray absorption [15] [14] | Ease of functionalization, strong electromagnetic field enhancement, high light-to-heat conversion [14] | Drug delivery, biosensing, photothermal therapy, bioimaging [15] |

| Metal Oxide-Based | Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄), Zinc Oxide (ZnO), Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) [15] | Superparamagnetism (e.g., Fe₃O₄), Photocatalytic activity, High specific surface area [15] | High stability & biocompatibility, ability to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) [15] | Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), targeted drug delivery, antimicrobial therapy [15] |

| Quantum Dots | Cadmium Selenide (CdSe), Cadmium Sulfide (CdS), Graphene Quantum Dots [15] | Size-tunable photoluminescence, broad excitation spectrum, quantum confinement effect [15] | High luminescence efficiency & stability superior to fluorescent dyes, surface modifiability [15] | Bioimaging, biosensing, photodynamic therapy, drug delivery [15] |

Performance Data in Drug Delivery and Therapeutics

The utility of inorganic nanosystems extends beyond their intrinsic properties to their demonstrated performance in experimental therapeutic applications. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from key studies in drug delivery and cancer treatment.

Table 2: Experimental Performance of Inorganic Nanosystems in Drug Delivery and Therapeutics

| Nanosystem | Application/Effect | Experimental Findings/Performance | Key Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Photothermal Therapy [14] | Efficient light-to-heat conversion under NIR irradiation for localized tumor ablation [14] | Anisotropic structures (nanorods, nanostars) used due to plasmon absorption in NIR region [14] |

| Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄) Nanoparticles | Thermal Ablation / Magnetic Hyperthermia [15] | Approved for clinical use (NanoTherm) for glioblastoma treatment via magnetic field-induced heating [15] | Localized activation by external magnetic field, minimizing systemic toxicity [15] |

| Carbon Quantum Dots | Photodynamic Therapy & Immunotherapy [15] | Derived from coffee, shown to induce ferroptosis in cancer cells and activate tumor immunity [15] | 660 nm laser excitation generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) [15] |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | Photocatalytic Tumor Cell Destruction [15] | Generates ROS under UV/visible light excitation, disrupting intracellular metabolism [15] | Photoexcitation leads to electron-hole pairs producing cytotoxic ROS [15] |

| Hafnium Oxide (HfO₂) Nanoparticles | Radiotherapy Enhancement [15] | Approved product (Hensify) for locally advanced soft tissue sarcomas [15] | Acts as a radio-enhancer, improving efficacy of radiotherapy [15] |

Essential Synthesis and Functionalization Protocols

The reproducible synthesis and functionalization of inorganic nanosystems are critical to harnessing their properties for biomedical applications. Below are detailed protocols for creating and modifying these nanoparticles.

Synthesis Methodologies

Chemical Reduction (for Metal Nanoparticles): This is a foundational wet-chemical method for producing zero-valent metal nanoparticles like silver and gold.

- Procedure: An aqueous salt of the metal (e.g., AgNO₃ for silver nanoparticles) is reduced using a chemical reductant such as sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) or citrate. The reducing agent provides electrons that convert metal ions (Ag⁺) to their neutral, metallic state (Ag⁰). A stabilizing agent like cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) is simultaneously added to control nanoparticle growth and prevent aggregation. [17]

- Key Parameter Control: The type and concentration of the reducing and stabilizing agents determine the final size and shape of the nanoparticles. [17]

Coprecipitation (for Metal Oxide Nanoparticles): This is a common and straightforward method for synthesizing magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles.

- Procedure: A mixture of ferrous (Fe²⁺) and ferric (Fe³⁺) chloride salts in a 1:2 molar ratio is vigorously stirred in an aqueous solution at an elevated temperature (e.g., 70°C). Ammonium hydroxide (NH₄OH) is then added to the solution, resulting in the instantaneous formation of a black precipitate of Fe₃O₄ (magnetite). The nanoparticles are collected via magnetic separation and purified with water and ethanol. [17]

- Key Parameter Control: The pH and ionic concentration of the solution are critical factors for controlling nanoparticle size. [17]

Seeding Growth Method (for Controlled Size/Shape): This method provides superior control over the size and morphology of metal nanoparticles.

- Procedure: Small, monodisperse "seed" nanoparticles are first synthesized (e.g., via chemical reduction). These seeds are then added to a second solution containing additional metal salt (e.g., HAuCl₄), a weak reducing agent (like hydroquinone), and stabilizers. The seeds catalyze the reduction of metal ions onto their surface, leading to controlled growth. This allows for the synthesis of larger nanoparticles (e.g., 30–300 nm) with defined shapes. [17]

Surface Functionalization Protocols

Functionalization is essential to make INPs biocompatible, stable in physiological environments, and capable of targeted delivery.

- Ligand Exchange/Conjugation: The surface of INPs can be modified with molecules possessing functional groups like thiols, amines, or carboxyls. These groups have a high affinity for inorganic surfaces (e.g., thiols for gold) and can be used to tether biomolecules. [17] [14] For instance, antibodies, aptamers, or DNA strands can be conjugated to the nanoparticle surface to enable active targeting to specific cells, such as cancer cells. [13] [15]

- Silica Coating: An inverse microemulsion method can be used to create a silica shell around nanoparticles. This coating stabilizes the core nanoparticle, prevents oxidation (especially for magnetic cores), and provides a chemically versatile silica surface that is easily functionalized with a wide range of organosilane chemistry, enhancing biocompatibility. [17]

- Polymer Encapsulation: Nanoparticles can be encapsulated within or coated with biocompatible polymers (e.g., polyethylene glycol, PEG). This "PEGylation" increases hydrophilicity, improves stability, and, crucially, helps the nanoparticles evade the immune system, thereby prolonging their circulation time in the bloodstream. [13] [15]

Visualizing Synthesis and Functionalization Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of nanoparticle synthesis and the relationship between their structure and function.

Synthesis and Functionalization Pathway

Structure-Property-Function Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation with inorganic nanosystems requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items and their functions in synthesis and functionalization protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Inorganic Nanosystem Development

| Reagent/Material | Core Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroauric Acid (HAuCl₄) | Gold precursor salt for synthesis | Starting material for seed-mediated growth of gold nanorods and spherical nanoparticles [17] |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Silver precursor salt | Primary ion source for chemical reduction synthesis of silver nanoparticles [17] |

| Ferrous/Ferric Chlorides (FeCl₂/FeCl₃) | Iron precursors | Used in co-precipitation synthesis of magnetite (Fe₃O₄) nanoparticles at 1:2 molar ratio [17] |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH₄) | Strong reducing agent | Rapid reduction of metal salts to form small seed nanoparticles in initial synthesis stages [17] |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Surfactant and stabilizing agent | Shape-directing agent for gold nanorod synthesis; prevents aggregation in aqueous solution [17] |

| Citrate | Weak reducing agent & stabilizer | Used in Turkevich method for gold nanoparticle synthesis; provides electrostatic stabilization [17] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-Thiol | Stealth coating polymer | Conjugates to gold surfaces via thiol group; improves biocompatibility and circulation time [15] [14] |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Silane coupling agent | Functionalizes silica-coated nanoparticles with amine groups for subsequent bioconjugation [17] |

| Hydroquinone | Weak reducing agent | Used in seeding growth method to slowly reduce metal ions onto existing nanoparticle seeds [17] |

Inorganic nanosystems provide a versatile and powerful platform for advancing nanomedicine, offering a complementary set of capabilities to organic nanomaterials. Their unique, engineerable optical and magnetic properties—such as plasmon resonance, superparamagnetism, and size-tunable fluorescence—enable sophisticated applications in targeted drug delivery, high-resolution bioimaging, and innovative therapeutic modalities like photothermal and photodynamic therapy. The ongoing challenge lies in optimizing their synthesis for monodispersity and scalability, ensuring long-term biocompatibility, and navigating the regulatory pathway to clinical translation. As research continues to refine the functionalization of these materials and deepen our understanding of their interactions with biological systems, inorganic nanosystems are poised to play an increasingly critical role in the development of next-generation diagnostic and therapeutic tools.

In the rapidly evolving field of nanomedicine, the strategic design of nanoparticles hinges on a deep understanding of their fundamental physicochemical properties. For researchers and drug development professionals, the comparative analysis of organic and inorganic nanosystems reveals a complex trade-off between biodegradability and stability, between biological compatibility and multifunctional capability. This guide provides an objective comparison centered on three pivotal properties—size, surface charge, and functionalization—that dictate nanoparticle behavior in biological environments. Through structured data and experimental protocols, we illuminate how these parameters influence cellular uptake, biodistribution, and therapeutic efficacy, providing a critical framework for selecting and engineering nanoparticles for targeted applications.

Core Properties Comparison: Organic vs. Inorganic Nanoparticles

The selection between organic and inorganic nanoparticles is foundational to nanomedicine research. The table below summarizes their characteristic properties, advantages, and limitations based on these core attributes.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Organic and Inorganic Nanoparticles

| Property | Organic Nanoparticles | Inorganic Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| General Composition | Polymers, lipids, proteins, carbohydrates (e.g., PLGA, Chitosan, Liposomes) [1] [18] | Metals, metal oxides, carbon allotropes, silica (e.g., Gold, Silver, Iron Oxide, ZnO) [1] [14] |

| Key Advantages | Biodegradable, biocompatible, often non-toxic, capacity for controlled drug release [1] [14] | High stability, tunable optical/magnetic/electronic properties, superior drug loading capacity [1] [14] |

| Key Limitations | Poorer stability, shorter shelf-life, low drug encapsulation efficacy in some cases [14] | Potential cytotoxicity, non-biodegradability, complexity in synthesis [19] [14] |

| Size Control | Dependent on synthesis method (e.g., solvent displacement, emulsion); can be highly precise [18] | Controllable via synthesis parameters (e.g., precursor concentration, temperature); wide range of sizes achievable [19] |

| Surface Charge | Highly tunable via polymer terminal groups or lipid composition [20] | Readily modifiable via direct covalent functionalization or polymer coating [13] [20] |

| Functionalization Ease | High; surface often readily amenable to conjugation [1] | High; well-established chemistry for ligand attachment (e.g., using thiols, silanes) [13] [20] |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Analysis of Key Properties

A deeper understanding requires examining quantitative data on how these properties directly impact biological interactions and performance.

Impact of Size on Cellular Uptake and Biodistribution

The size of a nanoparticle is a primary determinant of its journey through the body and into cells. It influences circulation time, organ accumulation, and the mechanism of cellular internalization.

Table 2: Size-Dependent Effects on Nanoparticle Behavior

| Size Range | Cellular Uptake Pathway | Key Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|

| < 10 nm | Passive diffusion, some endocytic pathways [21] | Rapid renal clearance, deep tissue penetration, but may exhibit increased toxicity [18] [21] |

| ~20-100 nm | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis, Caveolin-mediated endocytosis [21] | Optimal for prolonged circulation and efficient cellular uptake (e.g., spherical Ag NPs of 20-30 nm) [19] |

| > 100 nm | Phagocytosis, Macropinocytosis [21] | Often rapidly cleared by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), suitable for vaccine delivery [18] [21] |

Supporting Experimental Data: A study on Silver Nanoparticles (Ag NPs) demonstrated that their size directly influences antimicrobial potency. Research indicated that smaller Ag NPs (10-30 nm) exhibited stronger bactericidal effects compared to larger particles, attributed to a higher surface-area-to-volume ratio and increased ion release [1]. Another experiment on ZnO nanoparticles confirmed that bactericidal efficacy increased proportionally as the particle size decreased [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Size-Dependent Cellular Uptake

- Objective: To quantify the internalization efficiency of nanoparticles of varying sizes by a specific cell line (e.g., macrophages or cancer cells).

- Materials:

- Test Nanoparticles: A series of fluorescently labeled, charge-neutralized nanoparticles (e.g., polystyrene latex, PLGA, or silica) with diameters of 20 nm, 50 nm, 100 nm, and 200 nm.

- Cell Line: HeLa cells or RAW 264.7 macrophages.

- Reagents: Cell culture media (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), trypsin-EDTA, paraformaldehyde (4%), flow cytometry buffer.

- Equipment: CO₂ incubator, flow cytometer, fluorescent microscope [21].

- Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in 12-well plates at a density of 2 x 10⁵ cells/well and culture for 24 hours.

- NP Exposure: Incubate cells with nanoparticles of different sizes at a standardized concentration (e.g., 50 µg/mL) for 4 hours.

- Washing: Remove the NP-containing medium and wash the cell monolayer thrice with PBS to remove non-internalized particles.

- Harvesting: Trypsinize the cells, neutralize with media, and collect by centrifugation.

- Analysis: Resuspend the cell pellet in flow cytometry buffer and analyze the fluorescence intensity of 10,000 cells per sample using a flow cytometer. Higher fluorescence indicates greater NP uptake [21].

- Expected Outcome: Typically, nanoparticles in the 40-80 nm range show peak uptake efficiency for many cell types, while those below 10 nm or above 200 nm show significantly reduced internalization.

The Role of Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) in Bio-Interactions

Surface charge, typically measured as zeta potential, governs nanoparticle interactions with plasma membranes, proteins, and determines colloidal stability.

Table 3: Effects of Surface Charge on Nanoparticle Fate

| Surface Charge | Protein Corona & Circulation | Cellular Uptake & Interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Positive ( > +20 mV) | Attracts negatively charged proteins (e.g., albumin), may lead to opsonization and rapid clearance from blood [21]. | Strong electrostatic attraction to negatively charged cell membranes; generally promotes highest uptake but can increase cytotoxicity [20] [21]. |

| Neutral ( -10 to +10 mV) | Minimizes non-specific protein adsorption; promotes "stealth" properties and prolonged circulation [21]. | Reduced non-specific interaction; uptake relies more on specific targeting ligands; generally low cytotoxicity. |

| Negative ( < -20 mV) | May attract specific opsonins; can be designed to avoid accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon [21]. | Can experience electrostatic repulsion from cell membranes; uptake is typically lower than for cationic particles [20] [21]. |

Supporting Experimental Data: Functionalization plays a critical role in modulating charge. Coating inorganic nanoparticles with polyethylene glycol (PEG) can shield a positive charge, reducing non-specific interactions and prolonging circulation time [20] [19]. Conversely, coating with cationic polymers like polyethyleneimine (PEI) creates a highly positive surface, enhancing the adsorption and delivery of negatively charged nucleic acids like DNA and RNA [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Determining Zeta Potential and Protein Corona

- Objective: To measure the surface charge of nanoparticles and analyze how it affects protein adsorption in a biological fluid.

- Materials:

- Test Nanoparticles: Lyophilized samples of organic (e.g., chitosan, PLGA) and inorganic (e.g., gold, silica) nanoparticles with varied surface chemistries.

- Dispersant: Deionized water and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Biological Fluid: Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) or human plasma.

- Equipment: Zeta potential analyzer, dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument, ultracentrifuge [18] [21].

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Disperse nanoparticles in DI water and PBS at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. Sonicate to ensure homogeneity.

- Zeta Potential Measurement: Load the sample into a folded capillary cell and measure the zeta potential using a zeta potential analyzer. Perform triplicate measurements.

- Protein Corona Formation: Incubate a separate set of nanoparticles in 50% FBS at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Hard Corona Isolation: Centrifuge the NP-protein complex at high speed (e.g., 14,000 rpm) for 30 minutes to remove unbound proteins. Wash the pellet gently and re-centrifuge.

- Analysis: Re-suspend the hard corona-coated nanoparticles in PBS and measure the zeta potential again. The shift in value indicates the formation and nature of the protein corona [20] [21].

- Expected Outcome: The initial zeta potential will indicate colloidal stability (values > |±30| mV are considered stable). After corona formation, the zeta potential often shifts towards the charge of the predominant adsorbed proteins, providing insight into the nanoparticle's new biological identity.

Functionalization Strategies for Enhanced Targeting and Control

Functionalization involves engineering the nanoparticle surface with specific molecules to impart new functions, such as active targeting, stealth properties, or stimulus-responsiveness.

Table 4: Common Functionalization Strategies and Their Outcomes

| Functionalization | Mechanism | Experimental Outcome & Application |

|---|---|---|

| PEGylation | Creates a hydrophilic "stealth" layer that reduces opsonization and extends circulation half-life [20] [19]. | Up to 10-20x longer circulation time observed for PEGylated AuNPs compared to non-PEGylated counterparts [14]. |

| Targeting Ligands (e.g., Folic Acid, Antibodies) | Enables active targeting via receptor-ligand interaction (e.g., folate receptor on cancer cells) [19]. | Folic-acid-functionalized Ag NPs showed a 2-3 fold increase in cellular uptake in folate-receptor-positive cancer cells vs. negative cells [19]. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Polymers (e.g., pH-sensitive) | Undergoes conformational or charge changes in response to tumor microenvironment (lower pH) [20]. | Enhanced drug release (e.g., >50% at pH 5.0 vs. <10% at pH 7.4) demonstrated in vitro for cancer therapy [20]. |

| Cationic Polymer Coating (e.g., PEI, Chitosan) | Confers positive charge for complexation with genetic material (DNA, siRNA) and enhances endosomal escape [20]. | Significant increase in gene transfection efficiency compared to naked nucleic acids, though cytotoxicity must be monitored [20]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Ligand Functionalization for Targeted Delivery

- Objective: To functionalize silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) with folic acid and evaluate their targeted uptake in cancer cells.

- Materials:

- Nanoparticles: Spherical Ag NPs (20 nm).

- Ligand: Folic Acid (FA).

- Coupling Agent: 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS).

- Cell Lines: KB cells (folate receptor-positive) and A549 cells (folate receptor-negative).

- Equipment: UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, FTIR, Fluorescence Microscope [19].

- Methodology:

- Activation: Activate the carboxyl groups of folic acid using EDC/NHS chemistry in an aqueous buffer for 30 minutes.

- Conjugation: Mix the activated FA solution with the Ag NP suspension. Stir gently for 12 hours at room temperature.

- Purification: Purify the FA-conjugated Ag NPs (FA-Ag NPs) by centrifugation and washing to remove unreacted reagents.

- Characterization: Confirm conjugation using UV-Vis spectroscopy (shift in surface plasmon resonance) and FTIR (appearance of characteristic amide bonds).

- Cellular Uptake Test: Incubate KB and A549 cells with both bare Ag NPs and FA-Ag NPs. After 2 hours, wash the cells and image using a fluorescence microscope (if NPs are fluorescently labeled) or quantify uptake via ICP-MS [19].

- Expected Outcome: FA-Ag NPs will show significantly higher uptake in KB cells compared to bare Ag NPs, while uptake in A549 cells will be low and non-specific for both NP types, demonstrating successful active targeting.

Cellular Uptake Pathways Visualized

The following diagram illustrates the primary cellular uptake pathways for nanoparticles, which are heavily influenced by their physicochemical properties.

Diagram Title: Nanoparticle Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Reagents for Nanoparticle Synthesis, Functionalization, and Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Relevance to Property Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Silane coupling agent for introducing amine (-NH₂) groups on silica and metal oxide surfaces [20]. | Confers a positive surface charge for electrostatic adsorption of biomolecules or further conjugation. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer used for "PEGylation" to create a stealth layer, reducing immunogenicity and improving stability [20] [19]. | Modifies surface properties to increase hydrophilicity and circulation time, indirectly affecting size via coating. |

| Folic Acid | A common targeting ligand for cancer cells overexpressing the folate receptor [19]. | Used in functionalization to demonstrate active targeting and enhance cellular uptake specificity. |

| EDC / NHS Chemistry | Zero-length crosslinkers for catalyzing amide bond formation between carboxyl and amine groups [20]. | The standard method for covalent functionalization of ligands onto nanoparticle surfaces. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | A cationic polymer for coating nanoparticles or complexing nucleic acids [20]. | Dramatically alters surface charge to highly positive, facilitating gene delivery and membrane interaction. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Instrumentation to measure the hydrodynamic size and size distribution of nanoparticles in suspension [18]. | Essential for size characterization and stability assessment. |

| Zeta Potential Analyzer | Instrumentation to measure the electrokinetic potential of nanoparticles [18]. | The primary tool for quantifying surface charge and predicting colloidal stability. |

The comparative analysis of organic and inorganic nanoparticles reveals that no single nanomaterial class is inherently superior. The optimal choice is a deliberate compromise dictated by the application. Organic nanosystems, with their biodegradability and low toxicity, excel in drug delivery where long-term persistence is a concern. Inorganic nanosystems, with their superior stability and unique physicochemical properties, are unparalleled for theranostics, imaging, and applications requiring external energy activation like photothermal therapy. Ultimately, the "magic bullet" in nanomedicine is not found in the material alone, but in the precise engineering of its size, surface charge, and functionalization to navigate the biological landscape and execute its therapeutic mission with high fidelity. This guide provides the foundational data and methodological framework to empower researchers in making that critical engineering decisions.

The period from 2025 to 2033 represents a pivotal era in nanotechnology research and commercialization, particularly in the rapidly evolving fields of inorganic and organic nanosystems. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the comparative landscape of these material platforms is essential for strategic decision-making. Nanosystems, broadly categorized as inorganic, organic, and hybrid materials, represent engineered structures at the nanoscale (typically 1-100 nanometers) that exhibit unique properties differing from their bulk counterparts. Inorganic nanosystems include materials such as metal nanoparticles (gold, silver), metal oxides (titania, silica), and quantum dots, characterized by their robust structural integrity, defined crystallinity, and distinctive electronic, optical, and magnetic properties. Organic nanosystems encompass lipid-based nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, dendrimers, and other carbon-based structures, which offer advantages in biocompatibility, biodegradability, and synthetic versatility.

The fundamental distinction between these platforms lies in their composition, synthesis methodologies, and inherent material properties. According to IUPAC recommendations, hybrid organic-inorganic materials constitute a separate class where components interact through weak bonds (Class I) or strong covalent/ionic-covalent bonds (Class II), creating synergistic properties not found in the individual components [22]. This comparative guide examines the market trajectories, research applications, and experimental evidence for these nanosystem categories, providing an objective analysis of their relative performance in biomedical applications, with particular emphasis on drug delivery systems.

Market Outlook: Quantitative Growth Trends (2025-2033)

Global Market Size and Projections

Table 1: Global Market Size Projections for Nanotechnology Sectors (2025-2033)

| Sector Category | 2024 Base Value (USD Billion) | 2033 Projected Value (USD Billion) | Projected CAGR (%) | Primary Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Nanotechnology Market [23] | 11.4 | 102.8 | 27.68 | Healthcare applications, electronics, energy storage, and aerospace |

| Overall Nanomaterials Market [24] | 36.73 | 136.47 | 14.91 | Electronics, healthcare, energy storage, sustainable solutions |

| Inorganic Nanomaterials Market [25] | ~15 (2025 est.) | ~45 (2033 est.) | ~12 | Electronics, medical applications, chemical manufacturing |

| Nanomedicine Market [26] | 294.04 | 779.19 | 10.86 | Targeted drug delivery, cancer therapeutics, diagnostics |

| Non-Polymeric Organic Nanomaterial Market [27] | 2.41 (2025 est.) | 5.73 (2033 est.) | 11.44 | Drug delivery, medical imaging, energy storage |

Regional market dynamics reveal North America currently dominates the nanotechnology landscape with over 32.7% market share in the overall nanomaterials market and 49.9% in the nanomedicine sector, driven by robust R&D investments, strong government support through initiatives like the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI), and a high concentration of leading pharmaceutical and technology companies [24] [26]. The Asia-Pacific region is anticipated to exhibit the fastest growth rate during the forecast period, fueled by expanding manufacturing capabilities, government investments in energy and power infrastructure, and growing healthcare sectors in China, Japan, and India [28].

Market Segment Analysis by Application

Table 2: Application Market Share Analysis by Nanomaterial Type

| Application Sector | Dominant Nanomaterial Type | Market Share/Value (2024) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Oncology [26] | Organic & Inorganic Nanoparticles | 32.5% of nanomedicine market | Targeted drug delivery, diagnostics, imaging |

| Electronics [25] [24] | Inorganic Nanomaterials | $4 billion (inorganic nanomaterials) | Semiconductors, sensors, conductive pastes, batteries |

| Chemical Manufacturing [25] | Inorganic Nanomaterials | $5 billion (inorganic nanomaterials) | Catalysts, adsorbents, chemical processes |

| Healthcare (Overall) [24] | Mixed (Organic Dominant) | 33.2% of nanomaterials market | Drug delivery, diagnostics, medical imaging, biosensors |

The therapeutic segment leads nanomedicine applications with 34.7% market share, while nanoparticles constitute 76.7% of nanomolecule types used in medical applications [26]. Within inorganic nanomaterials specifically, the market is segmented by type with nano-oxides dominating (estimated at $8 billion), followed by nanometallic and alloys ($4 billion), and nanocomposite oxides ($3 billion) [25].

Comparative Performance Analysis: Inorganic vs. Organic Nanosystems

Experimental Comparison in Tumor Model Delivery

A critical 2024 study directly compared the passive targeted delivery efficiency of inorganic versus organic nanocarriers across different tumor types, providing valuable experimental data for drug development professionals [8]. The research evaluated four types of nanoparticles with similar sizes but different chemical structures: inorganic (Au and SiO2) and organic (PLA and CaCO3) nanoparticles.

Experimental Protocol:

- Nanoparticle Synthesis:

- PLA NPs: Synthesized using nano-precipitation method with dichloromethane, acetone, and ethanol as solvents

- Au NPs: Seed-mediated growth approach

- CaCO3 NPs: Co-precipitation method

- SiO2 NPs: Sol-gel technique

- Characterization: All NPs demonstrated homogeneous size distributions and spherical morphology confirmed by TEM and SEM imaging

- In Vivo Evaluation: Testing in three different tumor models to assess delivery efficiency based on chemical structure and tumor type

Key Findings:

- Tumor Model Influence: Delivery efficiency was highly dependent on tumor model characteristics, with significant variations in accumulation patterns between different cancer types

- Chemical Structure Impact: Organic and inorganic nanosystems showed distinct delivery profiles, with performance varying based on specific tumor microenvironment conditions

- Surface Charge: NPs with neutral zeta potential or in the range of -10/+10 mV demonstrated higher delivery efficacy than NPs with strongly positive (>+10 mV) or negative (<-10 mV) zeta potential

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for comparing organic and inorganic nanoparticle delivery efficiency across different tumor models [8].

Performance Metrics in Drug Delivery Applications

Table 3: Comparative Performance Analysis of Organic vs. Inorganic Nanosystems in Biomedical Applications

| Performance Parameter | Organic Nanosystems | Inorganic Nanosystems | Hybrid Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Generally higher; biodegradable polymers (PLA, PLGA) approved for clinical use [26] | Variable; gold generally safe; some metal oxides show toxicity concerns [25] | Tunable based on composition; can optimize biocompatibility [22] |

| Targeting Efficiency | Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect; surface functionalization possible [8] | EPR effect; surface plasmon resonance (gold) for thermal therapy [8] | Synergistic targeting; multiple functionalization approaches [22] |

| Drug Loading Capacity | High for hydrophobic drugs; core encapsulation [26] | Variable; surface conjugation common; mesoporous silica has high surface area [25] | Combined loading strategies; enhanced capacity through hybrid interface [22] |

| Clearance Profile | Biodegradable polymers allow metabolic clearance [26] | Potential for long-term accumulation; size-dependent renal clearance [25] | Tunable clearance; can design for specific metabolic pathways [22] |

| Manufacturing Scalability | Established for some polymers; solvent-based challenges [26] | High-temperature synthesis; purity challenges at scale [25] | Complex synthesis; emerging scalable approaches [22] |

| Regulatory Approval Status | Multiple FDA-approved products (Doxil, Abraxane) [26] | Limited clinical translation; some imaging agents approved [8] | Emerging regulatory pathway; case-by-case evaluation [22] |

The comparative analysis reveals a critical trade-off: while organic nanosystems generally offer better biocompatibility and more established regulatory pathways, inorganic systems provide unique physical properties (optical, magnetic, electronic) that enable additional therapeutic and diagnostic functionalities. The low clinical translation rate of inorganic nanosystems (less than 1% of preclinical studies reach clinical practice) highlights the significant challenge in balancing efficacy with safety profiles [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Nanosystem Development and Characterization

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Matrix Materials | Polylactic acid (PLA), Polycaprolactone (PCL), Chitosan [8] [22] | Organic nanoparticle formation; biodegradable scaffold | PLA/PCL blends studied with nHA fillers for bone tissue engineering [22] |

| Inorganic Precursors | Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), Metal salts (chloroauric acid) [8] [22] | Sol-gel synthesis of silica NPs; seed-mediated growth of metal NPs | TEOS used in double-network polymer electrolytes for solid-state storage [22] |

| Functionalization Agents | Zwitterions, Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Targeting ligands [8] [22] | Surface modification for stealth properties; active targeting | Zwitterion polymerization creates electrolytes with high electrochemical windows [22] |

| Characterization Tools | TEM, SEM, Dynamic Light Scattering [8] | Size distribution, morphology, surface charge analysis | Essential for quantifying delivery efficiency and biodistribution [8] |

| Cell Culture Models | Cancer cell lines, 3D spheroids, Primary cells [8] | In vitro assessment of cytotoxicity and cellular uptake | Tumor model selection critically impacts delivery efficiency results [8] |

| Animal Tumor Models | Xenograft models, Patient-derived xenografts [8] | In vivo evaluation of targeting and biodistribution | Study showed delivery efficiency varies significantly by tumor model [8] |

Emerging Innovations and Research Directions (2025-2033)

Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Nanosystems

The most significant trend in the forecast period is the rapid development of hybrid organic-inorganic nanomaterials that combine the advantages of both platforms while mitigating their individual limitations. These systems are defined as "multi-component compounds with at least one of their organic or inorganic components in the nano-metric-size domain, which confers the material as a whole of greatly enhanced properties respecting the constitutive parts in isolation" [22]. The strategic advantage of hybrid systems lies in the synergistic interface between components, which can produce enhanced electrical, optical, mechanical, catalytic, and sensing properties not achievable with single-component systems.

Figure 2: Classification framework for hybrid organic-inorganic nanomaterials based on interface interactions [22].

Recent innovations demonstrate the potential of hybrid systems:

- Double-Network Polymer Electrolytes: Combining nonhydrolytic sol-gel reaction of tetraethyl orthosilicate with in situ polymerization of zwitterions creates solid-state energy storage devices with high strength, stretchability, and excellent interface compatibility with Li metal electrodes [22]

- Multifunctional Fibers: Integration of functionalized silver nanoparticles (0-3.5 wt%) into PLA matrices via centrifugal force-spinning creates fibers with enhanced thermomechanical behavior and high antibacterial activity at 1% nanoparticle concentration [22]

- Toughened Composite Laminates: Incorporation of nanofiber polymeric veils as toughening interleaves in fiber-reinforced composite laminates prevents delamination and enhances out-of-plane properties [22]

Sector-Specific Technological Innovations

Healthcare and Life Sciences:

- Sprayable Nanofibers: Self-assembling peptide amphiphile nanofibers that form scaffolds mimicking the extracellular matrix for accelerated wound healing [29]

- Non-Viral Delivery Systems: Neutral or negative DNA nanoparticles that avoid immune responses associated with viral vectors for gene delivery applications [29]

- Cancer Theranostics: Integration of diagnostic and therapeutic functions in single nanosystem platforms, with particular focus on improving penetration and accumulation in tumor tissues [26]

Electronics and Energy:

- Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Conductive Paste: Partnership between SiAT and Zeon Corporation to develop SWCNT pastes that boost lithium-ion battery efficiency with smaller amounts than conventional carbon black [24]

- Nanoclay Additives: Portland State University development of nanoclay additives for waterborne coatings that reduce water absorption while maintaining transparency, extending lifespan for infrastructure and automotive applications [29]

- Cadmium-Free Quantum Dots: Nanoco Group's development of quantum dots for display technologies, lighting, and imaging with enhanced performance and color purity [30]

Environmental and Sustainable Technologies:

- Cellulose Nanocrystal Pesticides: University of Waterloo development of aqueous nano-dispersions of pesticides using cellulose nanocrystals as sustainable carriers with enhanced efficiency [29]

- Nanocellulose Aerogel Flame Retardants: Northeastern University creation of aerogel from freeze-dried cellulose nanofibers and metallic phase MoS2 that improves fire resistance and reduces toxic substance release [29]

- Biopolymer Composite Films: North Carolina State University development of agarose and nanofibrillated chitosan composites as sustainable alternatives to petroleum-based packaging with better strength and barrier properties [29]

Key Player Landscape and Strategic Developments

The competitive landscape for nanosystems features established chemical giants, specialized nanotechnology firms, and research institutions driving innovation:

Leading Corporate Players:

- BASF SE: Maintains forefront position in sustainable nanomanufacturing with strengths in high-performance coatings, advanced polymers, and precision catalysts [30]

- Arkema SA: Leverages specialty chemicals expertise to develop innovative nanomaterials and nanocomposites with focus on green synthesis methods [25] [30]

- Merck KGaA: Recognized for pioneering work in nanotechnology for healthcare, electronics, and pharmaceuticals with strong regulatory compliance expertise [30]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.: Provides essential analytical instrumentation and electron microscopes for nanomaterial characterization and quality control [30]

- Cabot Corporation: Specializes in carbon-based nanomaterials including carbon nanotubes for enhanced conductivity, durability, and energy efficiency [30]

Strategic Industry Developments:

- Partnerships for Battery Technology: BASF partnership with Nanotech Energy to reduce lithium-ion battery CO2 emissions through localized supply chains [28]

- Academic-Corporate Collaborations: CBC Co. partnership with Nanoform Finland to apply nanomedicine engineering technology to Japanese pharmaceutical market [26]

- Research Infrastructure Investments: University at Albany establishment of College of Nanotechnology Science and Engineering to position as educational leader in nanotechnology semiconductor research [28]

- International Graphene Research: Abu Dhabi University collaboration with Sri Lanka Institute of Nanotechnology to establish Graphene Center as research and innovation hub [28]

The nanotechnology innovation ecosystem remains highly dynamic, with moderate levels of merger and acquisition activity expected to continue as companies seek to expand product portfolios and access new technologies and markets [25].

The comparative analysis of inorganic and organic nanosystems from 2025-2033 reveals a complex landscape where material selection requires careful consideration of application-specific requirements. Organic nanosystems currently dominate therapeutic applications where biocompatibility and regulatory pathway clarity are paramount, while inorganic systems offer unique advantages in diagnostic, electronic, and energy applications where their physical properties provide functionality not achievable with organic materials alone.

The most promising research direction emerges in hybrid organic-inorganic nanosystems that leverage synergistic interfaces to create enhanced properties not found in individual components. For researchers and drug development professionals, the key strategic implications include:

- Material Selection: Prioritize organic platforms for near-term therapeutic applications but invest in inorganic characterization for diagnostic and theranostic applications

- Research Focus: Develop expertise in hybrid material interfaces where the greatest performance breakthroughs are anticipated

- Translation Strategy: Address scalability and regulatory challenges early, particularly for inorganic systems where clinical translation rates remain low

- Characterization Investment: Advance analytical capabilities for understanding nanomaterial-biological interactions across different disease models

The convergence of nanotechnology with artificial intelligence, advanced manufacturing, and personalized medicine will continue to accelerate innovation through the forecast period, positioning nanosystems as fundamental enabling technologies across healthcare, electronics, energy, and environmental applications.

Synthesis and Application Frontiers: From Fabrication to Biomedical Breakthroughs

The strategic design and fabrication of nanosystems stand as cornerstones of modern nanotechnology, driving innovation across fields from biomedicine to energy storage. For researchers and drug development professionals, the selection of an appropriate fabrication technique is paramount, as it directly influences the structural hierarchy, functionality, and applicability of the final product. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three pivotal fabrication strategies: self-assembly, covalent bonding, and green synthesis methods. These techniques are evaluated within the broader context of comparative research on inorganic versus organic nanosystems, which exhibit fundamental differences in their composition, properties, and typical applications. Organic nanosystems, including polymeric nanoparticles, dendrimers, and liposomes, are often biodegradable and biocompatible, making them excellent candidates for drug delivery. In contrast, inorganic nanosystems, such as those based on metals, metal oxides, and semiconductors, frequently offer superior tunable optoelectrical properties, magnetic characteristics, and catalytic activity [1]. Understanding the capabilities and limitations of each fabrication method empowers scientists to make informed decisions tailored to their specific research goals, whether developing targeted therapeutics, advanced sensors, or new catalytic systems.

Fundamental Principles and Definitions

- Self-Assembly (SA) is defined as the autonomous organization of components into ordered patterns or structures without human intervention. It exploits spontaneous molecular interactions and can be driven by various forces, including capillary, magnetic, or electrostatic forces [31] [32]. This process is parallel in nature and can be applied to a wide size range, from millimeters to nanometers.

- Covalent Bonding in fabrication involves creating strong, directional electron-pair bonds between atoms to form stable molecules or networks. In nanomaterial assembly, this includes techniques like Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) and methods for immobilizing biomolecules onto surfaces through the formation of irreversible covalent linkages [33] [34].

- Green Synthesis represents a reliable, sustainable, and eco-friendly protocol for synthesizing a wide range of nanomaterials. It utilizes biological components—such as bacteria, fungi, yeast, algae, and plant extracts—or benign solvent systems like water to reduce metal salts into nanoparticles, minimizing the use of hazardous substances [35] [36].

Comparative Evaluation of Technique Performance

The following tables summarize the key characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of each fabrication method, providing a clear, data-driven comparison.

Table 1: Overall Comparison of Fabrication Techniques