Nanoscale Biological Interactions: Fundamentals for Advanced Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive review explores the fundamental principles governing interactions between nanoscale materials and biological systems, providing crucial insights for researchers and drug development professionals.

Nanoscale Biological Interactions: Fundamentals for Advanced Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the fundamental principles governing interactions between nanoscale materials and biological systems, providing crucial insights for researchers and drug development professionals. The article systematically examines how physicochemical properties of nanoparticles—including size, surface charge, and functionalization—dictate their behavior in biological environments. It covers both traditional and emerging biomimetic strategies for optimizing nanoparticle performance, addressing critical challenges such as immune clearance, targeting specificity, and biocompatibility. Through comparative analysis of various nanoplatforms and discussion of advanced characterization techniques, this work establishes a foundation for the rational design of next-generation nanomedicines with enhanced therapeutic efficacy and safety profiles.

The Nano-Bio Interface: Fundamental Interactions Governing Nanomaterial Behavior in Biological Systems

The interaction between nanoparticles (NPs) and biological systems is a cornerstone of modern nanomedicine and nanotoxicology research. The biological fate, efficacy, and safety of nanoparticles are predominantly governed by a triad of fundamental physicochemical properties: size, surface charge, and hydrophobicity. These properties collectively determine the behavior of nanoparticles at the nano-bio interface, influencing their cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking, biodistribution, and potential toxicological outcomes. A systematic understanding of these parameters is essential for the rational design of effective and safe nanomedicines, as well as for accurate risk assessment of incidental nanoparticle exposure. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these key properties, framed within the context of fundamental nanoscale biological interactions research for scientific and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Property Analysis and Quantitative Data

The following section synthesizes experimental and computational data on how specific physicochemical parameters direct biological interactions.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Nanoparticle Physicochemical Properties on Biological Interactions

| Property | Typical Measurement Techniques | Key Biological Effects | Representative Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [1] [2] | Cellular uptake efficiency, biodistribution, clearance pathway [3] [1] | NPs of 10-100 nm show optimal tissue penetration and reduced RES clearance [4]. NPs <10 nm undergo rapid renal clearance [4]. Smaller NPs often show higher tissue distribution and more severe effects than larger ones [3]. |

| Surface Charge | Zeta (ζ) Potential [5] [2] [6] | Cellular membrane interaction, protein corona composition, cytotoxicity [3] [7] [6] | Positive charges enhance attachment to negatively charged cell membranes, often leading to higher cytotoxicity [3] [7]. Cationic NPs with high surface charge density (>2.95 µmol/g) cause significant viability loss, oxidative stress, and inflammation, while those with low density (0.23 µmol/g) do not [6]. |

| Hydrophobicity | Contact angle, Chromatography, Fluorescent probes [8] | Protein adsorption, immune clearance, self-assembly, membrane integration [9] [4] [10] | Hydrophobic surfaces enhance plasma protein adsorption (opsonization), leading to rapid clearance by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS) [4]. Hydrophobic interactions drive the self-assembly of nucleic acid-based biomaterials and facilitate nanoparticle embedding into lipid membranes [9] [10]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Characterizing Nano-Bio Interactions

Protocol 1: Evaluating Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the role of surface charge density on macrophage and epithelial cell responses [6].

- Objective: To quantify the relationship between nanoparticle surface charge density and cellular toxicity outcomes.

- Materials:

- THP-1-derived macrophages, A549, and Calu-3 airway epithelial cells.

- Cationic carbon nanoparticles (CDs) with a similar ζ-potential (+20 to +27 mV) but varying surface charge density (0.23 to 4.39 µmol/g).

- Cell culture reagents (α-MEM/RPMI-1640, FBS, antibiotics).

- Multiplex cytotoxicity assay kit (e.g., CCK-8 for viability).

- Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) and Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM).

- Assay kits for oxidative stress (DCFH-DA), mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1), and lysosomal integrity (e.g., Acridine Orange).

- Procedure:

- Cell Exposure: Harvest, wash, and suspend cells in an appropriate buffer. Expose cells to escalating doses (e.g., 3 to 200 µg/mL) of the characterized NPs for 24 hours.

- Viability Assessment: Use a CCK-8 or similar assay to measure cell viability loss. Incubate cells with the reagent for 1-4 hours and measure absorbance at 450 nm.

- Cellular Uptake Analysis:

- FACS: After 4 hours of exposure, harvest cells, wash, and analyze the intrinsic fluorescence of the CDs using FACS to quantify uptake.

- CLSM: Seed cells on glass-bottom dishes, expose to NPs, fix, and image using CLSM to visualize intracellular localization.

- Mechanistic Toxicity Profiling:

- Oxidative Stress: Load cells with DCFH-DA dye, expose to NPs, and measure fluorescence intensity corresponding to ROS generation.

- Mitochondrial Function: Stain NP-exposed cells with JC-1 dye and analyze the shift from red (healthy) to green (depolarized) fluorescence.

- Lysosomal Integrity: Stain with Acridine Orange; a loss of red fluorescence indicates lysosomal membrane permeabilization.

- In Vivo Correlation: Adminerve NPs (e.g., via inhalation) to mouse models and assess bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for inflammatory cell infiltrate and pro-inflammatory cytokines to correlate in vitro findings with in vivo airway inflammation.

- Key Interpretation: This protocol establishes that surface charge density, not just the absolute ζ-potential, is a critical descriptor for predicting NP toxicity. High charge density correlates with significant viability loss, oxidative stress, and inflammation [6].

Protocol 2: Assessing Nanoparticle-Membrane Interactions via Computational Simulation

This protocol outlines a computational approach to systematically study the synergistic effects of NP properties on cellular entry pathways [10].

- Objective: To simulate and categorize the interactions between monolayer-protected nanoparticles and model cell membranes.

- Materials:

- High-performance computing (HPC) cluster.

- Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD).

- Coarse-grained or all-atom force fields.

- Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Parameter Space: Define a 3D parameter space: NP size (3-15 nm), surface charge/pKa (total charge from 0-140 e), and ligand chemistry (hydrophobic alkyls vs. hydrophilic PEG).

- Membrane Model: Construct a model cell membrane composed of zwitterionic DPPC lipids in a bilayer configuration.

- Simulation Box: Place the NP above the membrane surface in an aqueous solution with an ionic imbalance to create a transmembrane potential.

- Simulation Run:

- Equilibrate the system with the NP's position restrained for 0.2 µs.

- Release the NP and allow it to interact freely with the membrane for 1.2 µs of simulation time.

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the simulation output to categorize the final outcome of the interaction into one of four types:

- Outer Wrap: Membrane wraps the NP but no translocation; leads to endocytosis.

- Free Translocate: NP completely translocates across the membrane via a pore into the cytosol.

- Embedment: NP partially translocates and remains stably embedded within the membrane.

- Inner Attach: NP mostly translocates but remains attached to the inner membrane leaflet.

- System Setup:

- Key Interpretation: This simulation reveals that cellular entry pathways are determined synergistically by size, charge, and chemistry. Smaller, highly charged, hydrophilic NPs favor free translocation, while larger, less charged, hydrophobic NPs favor embedding or outer wrapping [10].

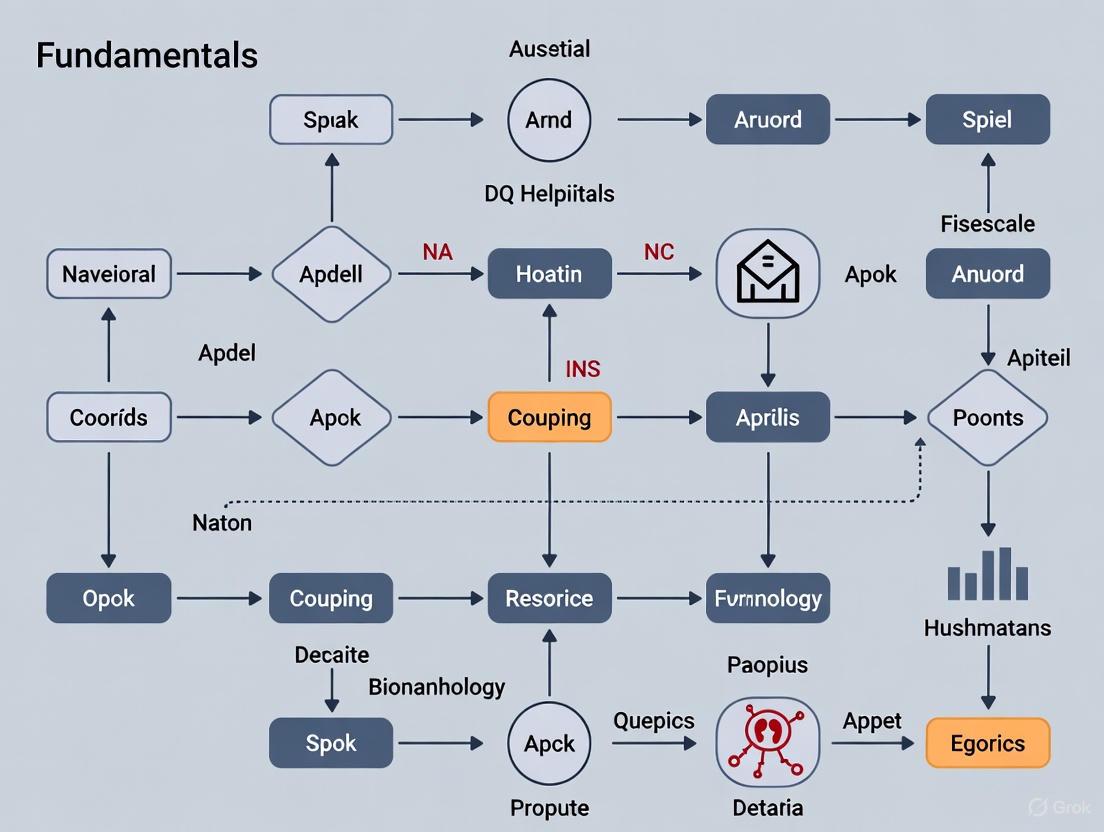

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for predicting nanoparticle-membrane interactions based on key physicochemical properties, as revealed by computational studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Nano-Bio Interaction Research

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Cationic Polymers | Functionalizing NPs to impart positive surface charge; nucleic acid condensation for gene delivery. | Branched Polyethylenimine (bPEI) of varying molecular weights (600 Da - 25 kDa) used to create carbon dots with high surface charge density [6]. |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | Surface coating to provide "stealth" properties, reduce protein adsorption, and prolong circulation half-life. | PEGylated liposomes (e.g., Doxil) show increased bioavailability and prolonged circulation [4]. PEG is a dominant coating in biodistribution studies [1]. |

| Amino Acids & Polyphenols | Acting as reducing and stabilizing agents in the "green" synthesis of bioactive metal nanoparticles. | Tyrosine, Tryptophan, Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG), and Curcumin used to synthesize and form a surface corona on gold and silver NPs [2]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) / ZetaSizer | Characterizing hydrodynamic size, size distribution (PDI), and zeta potential of nanoparticles in suspension. | Used to measure hydrodynamic diameter and ζ-potential of NPs in biological buffers [5] [2] [6]. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | High-resolution imaging of nanoparticle morphology, size, and surface roughness; also used to image NP-bacterial cell interactions. | Employed to determine the shape, size, and surface roughness of metal NPs and to visualize Rhodococcus cells after NP exposure [5]. |

The intricate biological interactions of nanoparticles are decisively guided by the triumvirate of size, surface charge, and hydrophobicity. A systematic and quantitative understanding of these properties is non-negotiable for advancing nanomedicine and conducting accurate nanotoxicological assessments. The experimental and computational methodologies outlined herein provide a robust framework for researchers to deconvolute these complex interactions. Future research must continue to embrace a holistic, multi-parameter approach to navigate the bio-nano interface, enabling the rational design of next-generation nanotherapeutics with optimized efficacy and safety profiles.

Upon entering a biological environment, nanoparticles (NPs) are rapidly coated by a dynamic layer of biomolecules, primarily proteins, forming what is known as the protein corona (PC) [11]. This biomolecular coating fundamentally redefines the nanoparticle's biological identity, dictating its subsequent interactions with biological systems [11] [12]. Rather than the pristine nanoparticle surface, it is the protein corona that is "seen" by cells, influencing critical outcomes such as cellular uptake, biodistribution, toxicity, and therapeutic efficacy [11] [13]. Understanding the composition, dynamics, and influence of the protein corona is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for the rational design of effective nanomedicines and the accurate assessment of nanomaterial safety [12] [14]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of protein corona formation, its determining factors, analytical methodologies, and its profound impact on nanoparticle fate within the context of nanoscale biological interactions research.

The Fundamentals of Protein Corona Formation and Structure

The formation of the protein corona is a spontaneous and dynamic process initiated the moment a nanoparticle encounters a biological fluid [14]. The structure is typically conceptualized in two distinct layers:

- The Hard Corona: Comprises proteins with high affinity for the nanoparticle surface, forming a stable, tightly bound layer through electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond interactions [11] [14]. This layer is relatively persistent and can remain attached for extended periods, even under dynamic biological conditions [14].

- The Soft Corona: Consists of proteins that are weakly associated with the hard corona or the nanoparticle surface itself through low-affinity, reversible interactions [12] [14]. This outer layer is highly dynamic, with a composition that fluctuates rapidly in response to changes in the surrounding environment [14].

This division is critical because the hard corona often dictates the long-term biological identity of the nanoparticle, while the soft corona can influence more transient interactions [12]. The entire structure is not static; it undergoes continuous evolution and re-equilibration as the nanoparticle transitions between different biological compartments (e.g., from blood to interstitial fluid), in a process that confers a form of molecular "memory" of the nanoparticle's journey through the body [14].

Table 1: Core Components of the Biomolecular Corona

| Component Type | Example Molecules | Significance & Interaction Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Albumin, Immunoglobulins, Apolipoproteins (e.g., ApoE, ApoA1), Complement factors [11] [13] | Determine biological response; adsorb via electrostatic/hydrophobic interactions [11] [14]. |

| Lipids | Phospholipids, Cholesterol, Fatty Acids, Triglycerides [14] | Contribute to structural stability and enhance biological mimicry through hydrophobic interactions [14]. |

| Other Biomolecules | Metabolites, Nucleic Acids, Carbohydrates [12] | Form a "complete corona"; can shape signaling and toxicity pathways [12]. |

Factors Governing Corona Composition and Dynamics

The precise composition of the protein corona is not random but is selectively determined by a complex interplay of nanoparticle physicochemical properties and biological environment factors [11] [12].

Nanoparticle Physicochemical Properties

- Size and Surface Curvature: Smaller nanoparticles, with their higher surface curvature and surface-to-volume ratio, exhibit different protein binding affinities and capacities compared to larger particles [11] [12].

- Surface Charge (Zeta Potential): Positively charged nanoparticles often exhibit more abundant protein adsorption due to electrostatic interactions with negatively charged domains of proteins [11]. Surface charge is consistently identified as one of the most significant NP-related predictors in machine learning models of corona composition [15].

- Surface Chemistry and Hydrophobicity: Hydrophobic surfaces tend to adsorb a greater amount of protein and can induce protein unfolding, leading to a more stable and less dynamic corona [14]. Surface functionalization (e.g., with carboxyl or amine groups) directly influences which proteins adsorb [12] [16].

- Core Material and Shape: The core material (e.g., gold, silica, lipid, iron oxide) and the geometric shape of the nanoparticle also contribute to the biological identity of the corona [11] [15].

Biological and Environmental Factors

- Protein Source and Concentration: The composition of the surrounding biological fluid (e.g., blood plasma, fetal bovine serum, interstitial fluid) is a primary determinant. The relative abundance of proteins in the biofluid is the most significant predictor of corona composition, as identified by machine learning models [15].

- Temporal Evolution: The corona is not static. The "Vroman effect" describes the dynamic process where proteins with high concentration and mobility (like albumin) arrive first at the nanoparticle surface but are later displaced by proteins with higher affinity, even if they are less abundant [14].

- pH and Temperature: Local environmental conditions such as pH and temperature can modulate protein structure and binding affinity, thereby influencing corona composition and stability [11].

Figure 1: Dynamics of Protein Corona Formation. The process involves initial adsorption influenced by NP properties, followed by dynamic exchange governed by the Vroman effect and environmental factors, ultimately establishing a stable hard corona, a dynamic soft corona, and a new biological identity.

Analytical Techniques for Protein Corona Characterization

Accurately characterizing the protein corona is methodologically challenging due to its dynamic nature and the risk of introducing artifacts during isolation [13] [14]. The following techniques are commonly employed, often in combination:

Separation and Isolation Techniques:

- Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation (DGU): A gentle method that separates protein-NP complexes from unbound proteins and endogenous biomolecules based on buoyant density. Critical for studying low-density nanoparticles like lipid NPs (LNPs) without inducing aggregation [13].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Separates complexes based on hydrodynamic size, helping to isolate them from free protein [13].

- Magnetic and Affinity-Based Separations: Useful for high-throughput studies but may require NP surface modification, which can alter the corona formation process [13].

Characterization and Identification Techniques:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Zeta Potential Measurement: Used to determine the hydrodynamic size and surface charge of nanoparticles before and after corona formation, providing information on adsorption and stability [11] [16].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS)-Based Proteomics: The gold standard for identifying and quantifying the protein composition of the corona. Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) enables deep, unbiased profiling of corona proteins [13] [17].

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): Measures the thermodynamics of protein-NP interactions, including binding affinity, stoichiometry, and enthalpy changes [11].

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Assesses whether proteins undergo structural changes (e.g., denaturation) upon adsorption to the nanoparticle surface [16].

- Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): Allows for direct visualization of the protein corona structure in a near-native state [14].

Table 2: Key Experimental Techniques for Protein Corona Research

| Technique | Key Measurable Parameters | Key Advantages | Common Challenges/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation | Buoyant density of protein-NP complexes [13]. | Gentle; preserves corona integrity; no modification needed [13]. | Time-consuming; requires optimization to separate from endogenous particles [13]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic diameter, polydispersity index (PDI) [11] [16]. | Fast; requires minimal sample preparation [11]. | Assumes spherical particles; sensitive to aggregates and dust [11]. |

| LC-MS Proteomics | Protein identity, relative/absolute abundance [13] [17]. | High-throughput; unbiased; deep coverage [17]. | Can be masked by highly abundant proteins; requires sophisticated data analysis [14]. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry | Binding constants (Kd), enthalpy (ΔH), stoichiometry (n) [11]. | Provides thermodynamic profile of interactions; label-free [11]. | Low throughput; requires significant amounts of sample [11]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Corona Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Workflow | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle Cores | Serves as the substrate for corona formation; core material is a key variable [15]. | Gold (Au), iron oxide (magnetic), polystyrene (PS), silica (SiO₂), lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [15] [13]. |

| Surface Ligands/Functionalizers | Modifies NP surface properties to study its impact on protein adsorption [15]. | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), carboxyl groups (-COOH), amine groups (-NH₂), citrate [15] [18] [16]. |

| Protein Sources | Provides the biological fluid environment for corona formation [15]. | Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), human plasma, mouse plasma [15] [16]. Critical to note interspecies differences [16]. |

| Stealth Proteins | Used for pre-coating ("engineering") the corona to achieve desired biological outcomes [16]. | Clusterin (ApoJ), Apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1). Their adsorption confers "stealth" properties [16]. |

| Proteomics Kits & Reagents | For sample preparation, digestion, and analysis in mass spectrometry [17]. | Proteograph Product Suite (uses multiplexed NPs for deep plasma proteomics) [17]. |

Impact on Nanomedicine: Therapeutic Efficacy and Safety

The protein corona directly impacts every aspect of a nanoparticle's performance in biomedical applications, often creating a paradox where it can either hinder or enhance functionality.

Disruption of Targeting and Accelerated Clearance

A primary challenge in nanomedicine is the uncontrolled formation of a protein corona, which can:

- Mask Targeting Ligands: Antibodies or other targeting moieties conjugated to the nanoparticle surface can be obscured by adsorbed proteins, preventing recognition of the intended cell surface receptor [18].

- Induce Opsonization: The adsorption of certain proteins (opsonins) can tag the nanoparticle for rapid recognition and clearance by phagocytic cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), primarily in the liver and spleen [11] [18]. This accelerated blood clearance (ABC) drastically reduces circulation half-life and delivery to the target tissue [11].

Strategic Exploitation of the Corona

Conversely, a growing research focus is on strategically exploiting the corona for beneficial outcomes:

- Engineered Stealth Coronas: Pre-coating nanoparticles with specific "dysopsonin" proteins like clusterin or ApoA1 can create a stealth corona that reduces immune recognition and extends circulation time [16]. The stability of this pre-formed corona in full plasma is a critical area of investigation [16].

- Leveraging Natural Targeting: The protein corona can be harnessed for natural targeting. For instance, the adsorption of Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) on lipid nanoparticles facilitates their uptake by hepatocytes via low-density lipoprotein receptors, a phenomenon that underpins the liver tropism of many LNP-based therapies [13].

- Biomimetic Coating Strategies: A powerful approach to control the bio-interface is to coat nanoparticles with natural cell membranes (e.g., from red blood cells, white blood cells, or cancer cells) [18] [19]. This top-down strategy endows the nanoparticle with the complex biological signaling functions of the source cell, enabling long circulation, immune evasion, or specific targeting [18].

Emerging Frontiers: AI Prediction and Advanced Materials

The field is rapidly evolving with the integration of new computational and design tools.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: The use of AI/ML to predict corona composition is a transformative approach to overcome the time and cost constraints of experimental methods. Random Forest models have been successfully trained on datasets of NP features (e.g., size, zeta potential), protein features, and experimental conditions to predict protein abundance and enrichment on nanoparticles with high accuracy [11] [15]. These models consistently identify protein abundance in the biofluid, NP zeta potential, and hydrodynamic diameter as the most important predictive features [15].

- Extension to Emerging Materials: The protein corona concept is now being applied to newer material classes like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), where corona formation can either stabilize or destabilize the framework and modulate its function [12].

- The "Complete Corona": Moving beyond a protein-centric view, the concept of the "complete corona" acknowledges the integral role of metabolites, lipids, and other small molecules in conjunction with proteins to determine a nanoparticle's biological fate [12].

Figure 2: Machine Learning Workflow for Corona Prediction. Random Forest and other ML models integrate features from nanoparticles, proteins, and experimental conditions to predict corona composition, aiding rational NP design.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Characterizing the LNP Protein Corona

The following protocol, adapted from current research, details a robust method for isolating and characterizing the protein corona on lipid nanoparticles, a clinically critical nanomaterial [13].

Objective: To isolate the hard protein corona from LNPs incubated in human plasma and identify its composition using label-free quantitative mass spectrometry proteomics, while avoiding co-isolation of endogenous plasma particles.

Materials:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Synthesized, e.g., with the ionizable lipidoid 306O10 [13].

- Biological Fluid: Human blood plasma (K2EDTA anticoagulant).

- Density Gradient Medium: OptiPrep or equivalent iodixanol solution.

- Equipment: Ultracentrifuge, swinging-bucket rotor, fractionation system, LC-MS system.

Procedure:

Corona Formation:

- Incurate LNPs (e.g., at a concentration of 1-2 mg/mL lipid) with human plasma (e.g., 90% plasma v/v) for 1 hour at 37°C with gentle agitation [13].

Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation (DGU) - Critical Step:

- Prepare a continuous density gradient (e.g., 0-30% iodixanol) in an ultracentrifuge tube.

- Carefully layer the LNP-plasma incubation mixture on top of the gradient.

- Centrifuge at 200,000 × g for 16-18 hours at 4°C [13]. Note: This extended duration is crucial for effective separation of LNPs from denser endogenous particles like lipoproteins and exosomes.

- After centrifugation, fractionate the gradient from the top. LNP-protein complexes will be found in low-density fractions.

Sample Preparation for Proteomics:

- Recover the LNP-containing fractions.

- Digest the proteins in these fractions using a standard tryptic digestion protocol (e.g., reduction with dithiothreitol, alkylation with iodoacetamide, and overnight trypsin digestion).

- Desalt the resulting peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction tips or columns.

LC-MS Analysis and Data Processing:

- Analyze the peptides by nano-flow Liquid Chromatography coupled to a high-resolution Mass Spectrometer (e.g., Orbitrap Astral or Exploris series) operating in Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) mode [13] [17].

- Process the raw MS data using specialized software (e.g., DIA-NN) against a human protein sequence database.

- Normalize protein intensities to those found in a control sample of plasma processed without LNPs to distinguish truly enriched "corona proteins" from background [13].

Key Considerations:

- Controls: Always include a "plasma-only" control processed identically to account for endogenous particles.

- Stability: Monitor LNP size and integrity post-DGU via DLS to ensure the isolation process did not cause aggregation or disruption.

- Validation: Functional validation of findings (e.g., via cellular uptake assays with pre-coated LNPs) is essential to link corona composition to biological effect [13].

The protein corona is an inescapable and defining interface in nanomedicine and nanotoxicology. Its composition, governed by the complex interplay of nanoparticle properties and biological environment, ultimately dictates the biological fate of nanomaterials. While the uncontrolled formation of a corona presents a significant barrier to targeted delivery, the strategic engineering of this layer—through pre-coating, biomimetic membrane cloaking, or rational design informed by AI—offers a powerful pathway to overcome these challenges. Future research focused on understanding the "complete corona," its evolution in dynamic physiological systems, and its specific impact on intracellular trafficking will be critical to fully harnessing the potential of nanotechnology in medicine. The ability to predict and control the protein corona represents the key to unlocking the next generation of safe, effective, and precisely targeted nanotherapeutics.

Nanoparticles have transformed contemporary medicine by improving the bioavailability, targeting, and release mechanisms of therapeutic agents [20]. The cellular internalization of nanomaterials is a critical process governing the efficacy of nanomedicines, influencing their distribution, subcellular localization, and eventual biological activity. Understanding these uptake mechanisms is fundamental to designing advanced drug delivery systems that can overcome biological barriers and achieve precise targeting [21]. This review provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the endocytosis pathways and intracellular trafficking behavior of nanomaterials, framed within the broader context of nanoscale biological interactions research for therapeutic applications.

The cellular uptake of nano- and microparticles has been extensively studied in static two-dimensional (2D) in vitro cultures, with thousands of publications exploring these phenomena [22]. However, the relevance of these studies for in vivo applications remains debatable, and the lack of standardized protocols makes comparative analysis challenging. This technical guide aims to synthesize current understanding while emphasizing quantitative parameters and methodologies essential for researchers and drug development professionals working in nanomedicine [22].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Nanoparticle Uptake

Sequential Uptake Process

Nanoparticle internalization by cells follows a multi-step process governed by complex biophysical interactions. In standard in vitro conditions, particles first reach cells through diffusion and sedimentation [22]. Upon contact, particles may adhere to the outer cell membrane through specific receptor-ligand interactions or non-specific forces such as electrostatic attraction [22]. Following a variable dwelling period, particles are typically internalized via endocytosis and subsequently trafficked through endosomal-lysosomal compartments [22]. The intracellular fate involves potential exocytosis, dilution during cell division, or sustained retention depending on particle characteristics and cell type [22].

Key Endocytosis Pathways

Different nanoparticle properties activate distinct endocytic mechanisms, each with unique characteristics and functional implications:

- Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis (CME): A receptor-mediated pathway utilized by specific ligands, such as the internalization of Fe₂O₃ nanoparticles in the liver via LDLR and TFR1 receptors [23].

- Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis: Involves flask-shaped membrane invaginations and can bypass lysosomal degradation.

- CLEC4E-Mediated Pathway: A clathrin- and caveolae-independent pathway identified as the primary mechanism for Fe₂O₃ nanoparticle uptake in the intestine [23].

- Macropinocytosis: A receptor-independent process involving actin-driven membrane ruffling that internalizes large volumes of extracellular fluid.

The selective activation of these pathways depends on the unique biomolecular corona that forms on nanoparticle surfaces in different biological milieus [23]. Studies demonstrate that identical nanoparticles can be internalized through distinct tissue-specific mechanisms depending on their corona composition [23].

Quantitative Analysis of Cellular Uptake

Essential Parameters for Quantification

Accurate quantification of nanoparticle uptake requires careful consideration of multiple experimental parameters that significantly influence results [22]. The table below summarizes critical factors that must be documented to enable meaningful cross-study comparisons.

Table 1: Essential Experimental Parameters for Quantitative Uptake Studies

| Parameter Category | Specific Factors | Impact on Uptake Quantification |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Characteristics | Concentration metrics (molar, mass, elemental), colloidal stability, batch-to-batch variation, degradation profile | Different metrics cannot be unequivocally converted; agglomeration enhances sedimentation and artificial uptake [22]. |

| Cell Culture Conditions | Cell density, medium height/volume, medium composition (serum content), proliferation rate, cell surface area/volume | Higher particle concentration in smaller volume increases uptake rate; serum depletion enhances uptake [22]. |

| Exposure Conditions | Incubation time, confluency state, temperature, particle-to-cell ratio | Uptake depends on cell density; incubation must be contextualized with proliferation rate [22]. |

Quantitative Uptake Parameters

Moving beyond qualitative descriptions ("better/faster/more"), rigorous quantification requires specific parameters extracted from uptake kinetics [22]. The "intensity" of particles per cell (I) plotted against incubation time (t) typically follows a saturating exponential curve, characterized by the maximum uptake (Iₘₐₓ) and the rate constant (k) [22]. These parameters allow direct comparison between different particle systems and cell types.

Methodologies for Uptake Quantification

Multiple analytical techniques are employed to quantify nanoparticle internalization, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications.

Table 2: Methodologies for Quantifying Nanoparticle Uptake by Cells

| Methodology | Measured Parameter | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Elemental concentration [22] | High sensitivity, quantitative [22] | Cannot distinguish internalized vs. membrane-adherent particles [22] |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy/ Microscopy | Fluorescence intensity [22] | Spatial resolution, live-cell capability [22] | pH-dependent quenching, fluorophore bleaching [22] |

| Single Particle Tracking | Individual particle movement [22] | Reveals real-time kinetics [22] | Technically challenging, limited throughput [22] |

| Flow Cytometry | Population-average fluorescence [22] | High-throughput, statistical power [22] | No subcellular localization [22] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Quantitative Uptake Using Elemental Analysis

- Cell Culture: Seed cells at precisely defined density (e.g., 50,000 cells/cm²) in standard multi-well plates and culture until desired confluency [22].

- Particle Exposure: Prepare particle suspensions in relevant culture medium, noting exact volume and height above cells. Apply to cells for predetermined incubation periods [22].

- Removal of Adherent Particles: After incubation, remove extracellular particles through extensive washing. Optional: Use digestive enzymes (trypsin) or chemical etching for extracellular particles when using elemental analysis [22].

- Sample Digestion: Lyse cells using appropriate digesting agents (e.g., nitric acid for metal-based nanoparticles) to completely liberate particulate elements [22].

- Quantification: Analyze digested samples using ICP-MS to determine elemental concentrations. Calculate particles per cell using standard curves and known cell counts [22].

Protocol for Distinguishing Internalized from Surface-Bound Particles

For fluorescence-based studies, these methods can differentiate internalized particles:

- Chemical Quenching: Add non-membrane-permeant quenchers (e.g., metal ions for quantum dots) to extinguish fluorescence from extracellular particles while preserving intracellular signal [22].

- Immunostaining: Colocalize particles with antibodies against endosomal/lysosomal markers (LAMP1, EEA1) to confirm intracellular localization [22].

- pH-Sensing: Use pH-sensitive fluorophores that activate only in acidic endolysosomal compartments [22].

Intestinal Barriers and Nanoparticle Uptake

Targeting the small intestine employing nanotechnology represents a promising approach for oral drug delivery due to its extensive surface area (300-400 m²) and less harsh environment compared to the stomach [21]. However, nanoparticles must overcome significant intestinal barriers to reach systemic circulation.

Mucus Barrier Penetration

The mucus layer, a hydrogel composed primarily of MUC2 mucin glycoproteins secreted by goblet cells, forms the primary physical barrier to oral nanoparticles [21]. This layer varies in thickness from 10-200 μm throughout the intestinal tract and is continuously shed and renewed [21]. Strategies to enhance mucus penetration include:

- Mucus-Penetrating Particles (MPPs): Surface functionalization with low molecular weight polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains creates neutral, hydrophilic surfaces that minimize mucin interactions [21].

- Surface Engineering: Dense charge-bearing neutral hydrophilic surfaces or albumin functionalization reduce mucus binding [21].

- Enzyme Modification: Nanoparticle decoration with proteolytic enzymes (e.g., papain) degrades mucoglycoprotein substructures to enhance penetration [21].

Epithelial Translocation

After penetrating the mucus, nanoparticles must cross the epithelial layer through either paracellular (between cells) or transcellular (through cells) pathways:

- Paracellular Transport: Involves temporary opening of tight junctions using permeation enhancers like chitosan [21].

- Transcellular Transport: Utilizes various endocytic pathways, with M-cells and enterocytes being the primary portals for nanoparticle internalization [21].

Visualizing Uptake Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Endocytosis Pathway Diagram

Quantitative Uptake Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nanoparticle Uptake Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Endocytic Inhibitors | Chlorpromazine (CME inhibitor), Filipin (caveolae inhibitor), Amiloride (macropinocytosis inhibitor) | Pathway-specific mechanistic studies to determine dominant uptake routes [23] |

| Fluorescent Tags | pH-sensitive dyes (LysoTracker), quantum dots, fluorescent antibodies against endosomal markers | Particle tracking and subcellular localization confirmation [22] |

| Surface Modifiers | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), chitosan, albumin, targeting ligands (RGD peptides, transferrin) | Enhanced stability, mucus penetration, and targeted cellular delivery [21] |

| Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials, standardized particle batches | Method validation and cross-study comparison [22] |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Defined serum concentrations, viability assay kits (MTT, WST-8) | Controlled exposure conditions and cytotoxicity assessment [22] |

The cellular uptake mechanisms of nanomaterials represent a complex interplay between particle physicochemical properties and biological systems. Understanding these processes at quantitative levels enables rational design of nanomedicines with optimized targeting and therapeutic efficacy. Future directions include developing standardized protocols for uptake quantification, advancing real-time imaging methodologies, and creating more sophisticated in vitro models that better recapitulate in vivo conditions. As research progresses, the integration of artificial intelligence and tailored nanomedicine design promises to further enhance our ability to manipulate these fundamental nanoscale biological interactions for improved therapeutic outcomes.

The efficacy of nanodelivery systems is fundamentally constrained by a series of biological barriers that impede the journey of a nanocarrier from the point of administration to its intended site of action within the body. These barriers operate sequentially and in concert, significantly limiting the bioavailability and therapeutic potential of nanomedicines. The first major hurdle is systemic circulation, where nanocarriers must navigate the vascular system while resisting opsonization and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). The second barrier is immune clearance, primarily mediated by the liver and spleen, which rapidly identify and remove foreign particles from the bloodstream. The final and perhaps most formidable barrier is tissue penetration, where nanocarriers must extravasate from the vasculature and diffuse through dense extracellular matrices to reach target cells. Understanding the mechanisms of these barriers is paramount for the rational design of advanced nanodelivery systems that can overcome these challenges. This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of these barriers, supported by quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualization tools for researchers in nanoscale biological interactions.

Blood Circulation Barrier

Physiological Challenges and Clearance Mechanisms

Upon intravenous administration, nanocarriers enter a dynamic and hostile environment within the bloodstream. The primary challenge in systemic circulation is prolonged retention, as the body's innate defense mechanisms work to clear foreign particles. The mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), also known as the reticuloendothelial system (RES), plays a pivotal role in this clearance, with macrophages in the liver (Kupffer cells) and spleen rapidly sequestering nanoparticles from circulation. Opsonization—the adsorption of plasma proteins (opsonins) such as immunoglobulins, complement proteins, and fibronectin onto the nanoparticle surface—serves as a biological tag that facilitates recognition and phagocytosis by MPS cells. The rate of clearance is influenced by several physicochemical properties of the nanocarriers, including size, surface charge, and hydrophobicity. For instance, larger particles (>200 nm) are typically cleared faster than smaller ones, and positively charged particles exhibit higher opsonization rates compared to their neutral or negatively charged counterparts.

Table 1: Impact of Nanoparticle Physicochemical Properties on Blood Circulation Half-life

| Property | Impact on Circulation | Optimal Range | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Determines MPS uptake and renal clearance | 10-100 nm | Particles <10 nm undergo renal clearance; >200 nm are sequestered by MPS [24] |

| Surface Charge | Affects opsonin protein adsorption | Neutral or Slightly Negative | Cationic surfaces promote opsonization and MPS uptake [24] |

| Hydrophobicity | Increases nonspecific protein adsorption | Hydrophilic | Hydrophobic surfaces attract more opsonins [25] |

| Shape | Influences margination and flow dynamics | Spherical or Ellipsoidal | Rod-shaped particles may exhibit longer circulation times than spherical ones [26] |

Strategic Solutions and Surface Engineering

To circumvent rapid clearance, surface functionalization has emerged as a primary strategy. PEGylation—the covalent attachment of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) chains—creates a hydrophilic steric barrier that reduces protein adsorption and MPS recognition, thereby extending circulation half-life. This "stealth" effect is the foundation of several clinically approved nanomedicines. More recently, biomimetic camouflage has shown remarkable promise. This involves coating synthetic nanocarriers with natural cell membranes (e.g., from erythrocytes, leukocytes, or platelets) to confer the nanoparticles with the same biological properties as the source cells. For example, erythrocyte membrane-coated nanoparticles display "self-marker" proteins like CD47, which binds to signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) on macrophages and transmits a "don't eat me" signal, effectively evading immune clearance.

Immune Clearance Barrier

Mechanisms of Immune Recognition

The immune system provides a sophisticated and multi-layered defense against nanocarriers that survive the initial MPS filtration. Immune clearance involves both innate and adaptive components. The complement system can be activated by nanoparticles via the classical, lectin, or alternative pathways, leading to opsonization by C3b and formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC), which can lyse certain lipid-based nanocarriers. Furthermore, nanoparticles can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on immune cells, triggering inflammatory responses and phagocytosis. A significant challenge in nanodelivery is the accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon, wherein repeated administration of PEGylated nanoparticles can induce anti-PEG IgM antibodies, leading to rapid clearance of subsequent doses.

Biomimetic Strategies for Immune Evasion

Biomimetic nanoplatforms represent a paradigm shift in overcoming immune clearance. By leveraging the natural biology of cells, these platforms are endowed with complex, biologically derived surfaces that are inherently adept at evading immune surveillance.

Table 2: Cell Membrane-Coated Nanoplatforms for Immune Evasion

| Membrane Source | Key "Self" Markers | Primary Evasion Mechanism | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythrocyte (Red Blood Cell) | CD47 | CD47-SIRPα "don't eat me" signaling [25] | Systemic circulation, prolonged delivery |

| Leukocyte (White Blood Cell) | CD45, CD47 | Mimics "self" leukocyte identity [25] | Targeting inflammatory and tumor sites |

| Platelet | CD47, CD55, CD59 | Evasion of phagocytosis and complement [27] [25] | Targeting damaged vasculature and thrombi |

| Cancer Cell | CD47, MHC-I | Homotypic targeting (homing to source tumor) [25] | Drug delivery to primary tumors and metastases |

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of how these biomimetic nanoparticles achieve immune evasion.

Tissue Penetration Barrier

The Tumor Microenvironment as a Model Challenge

The pathophysiological nature of solid tumors exemplifies the extreme challenge of tissue penetration. While the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect allows nanocarriers of a certain size (typically 10-200 nm) to extravasate through the leaky vasculature of tumors, their subsequent penetration into the tumor core is severely limited. The tumor microenvironment (TME) presents multiple obstacles: a dense extracellular matrix (ECM) rich in collagen and hyaluronic acid creates a physical barrier; high interstitial fluid pressure due to poor lymphatic drainage induces an outward convective force that opposes inward diffusion; and the complex architecture of cancer cells and stromal cells further hinders deep penetration. Consequently, nanoparticles often accumulate perivascularly, leading to heterogeneous drug distribution and suboptimal therapeutic outcomes.

Advanced Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Penetration

Innovative nanocarrier designs that can dynamically respond to the TME are critical for overcoming the penetration barrier. Key strategies include:

- Size-Transformable Nanosystems: These carriers are designed to undergo a size shift from large (>100 nm) to small (<50 nm) upon encountering a specific tumor-specific stimulus. The larger size is beneficial for prolonged circulation and initial tumor accumulation via the EPR effect, while the smaller size post-transformation enables deeper penetration into the tumor parenchyma.

- Charge-Reversal Nanoparticles: The surface charge of these nanocarriers is initially negative or neutral during circulation to minimize protein adsorption and MPS uptake. Upon entering the acidic TME (pH ~6.5-6.8), the surface chemistry triggers a switch to a positive charge, which enhances cellular uptake by facilitating interaction with the negatively charged cell membranes.

- Enzyme-Responsive Systems: These are engineered to be degraded or modified by enzymes that are overexpressed in the TME, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) or hyaluronidases. For instance, a nanocarrier can be decorated with a PEG corona linked via an MMP-cleavable peptide; upon reaching the tumor, MMPs cleave the peptide, shedding the PEG layer and potentially exposing a hidden, cell-penetrating surface.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the multi-stage journey of a nanocarrier and the design strategies employed to overcome each barrier.

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol: Quantifying Blood Circulation Half-life

Objective: To determine the pharmacokinetic profile and circulation half-life of a novel nanocarrier in a murine model.

Materials:

- Radiolabeled (e.g., 125I) or fluorescently labeled (e.g., DiR) nanocarrier.

- Animal model (e.g., BALB/c mice).

- Microcentrifuge tubes.

- Gamma counter or IVIS imaging system.

- Heparinized capillary tubes or equipment for retro-orbital bleeding.

Procedure:

- Administer the labeled nanocarrier to mice via tail vein injection (dose: e.g., 10 mg/kg).

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours) post-injection, collect blood samples (e.g., ~20 μL per time point) via retro-orbital bleeding or tail nick into heparinized tubes.

- Lyse the blood cells if necessary and measure the radioactivity or fluorescence intensity in each sample using a gamma counter or plate reader.

- Express the data as the percentage of injected dose per gram of blood (%ID/g) or milliliter (%ID/mL) over time.

- Fit the blood concentration-time data to a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model using software like Phoenix WinNonlin to calculate the alpha half-life (distribution phase, t1/2α) and beta half-life (elimination phase, t1/2β).

Protocol: Assessing Tumor Penetration Depth

Objective: To visualize and quantify the spatial distribution and penetration depth of nanocarriers within a tumor spheroid or ex vivo tumor tissue.

Materials:

- Fluorescently labeled nanocarrier.

- 3D Tumor spheroids (e.g., from U87MG cells) or excised tumor tissue.

- Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM).

- Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Imaris).

- Tissue freezing medium (OCT compound) and cryostat (for excised tumors).

Procedure: For Tumor Spheroids:

- Incubate mature spheroids with the fluorescent nanocarrier for a set duration (e.g., 4-24 h).

- Wash the spheroids thoroughly with PBS to remove non-internalized particles.

- Fix the spheroids with 4% paraformaldehyde.

- Transfer a spheroid to a glass-bottom dish and image using CLSM, acquiring Z-stack slices from the top to the bottom of the spheroid.

- Use ImageJ to plot the fluorescence intensity as a function of distance from the spheroid periphery. The penetration depth is defined as the distance at which the fluorescence intensity drops to 50% of its maximum value at the periphery.

For Excised Tumors:

- Administer the nanocarrier to tumor-bearing mice and sacrifice at a predetermined time.

- Excise, embed in OCT, and snap-freeze the tumor.

- Section the tumor into 10-20 μm thick slices using a cryostat.

- Stain for blood vessels (e.g., anti-CD31 antibody) and nuclei (DAPI).

- Image multiple random fields per section using CLSM.

- Quantify the distance from each fluorescent nanoparticle signal to the nearest CD31-positive blood vessel using the distance transform function in ImageJ. Calculate the average and distribution of these distances.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Nanodelivery Barriers

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| DSPE-PEG(2000) | Stealth lipid for liposomes and lipid NPs; extends circulation half-life by reducing opsonization [24]. | Amphiphilic, PEG molecular weight of ~2000 Da. |

| Cell Membrane Extraction Kits | For isolating pure plasma membranes from erythrocytes, leukocytes, etc., to create biomimetic coatings [25]. | Yields membranes with preserved protein function. |

| pH-Sensitive Polymers (e.g., PAA, PDEAEMA) | Backbone for constructing charge-reversal nanocarriers; protonated in acidic TME for enhanced uptake [24]. | pKa values tunable to specific pH thresholds (e.g., pH 6.5-7.0). |

| MMP-Substrate Peptides (e.g., GPLGVRGK) | Linker for enzyme-responsive nanocarriers; cleaved by MMP-2/9 in the TME to trigger payload release or surface transformation [24]. | High specificity and cleavage efficiency. |

| Near-Infrared Dyes (e.g., DiR, Cy7.5) | For non-invasive, real-time tracking of nanocarrier biodistribution and tumor accumulation using fluorescence imaging [28]. | Low background autofluorescence, deep tissue penetration. |

| Dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) | A helper lipid that promotes endosomal escape via the "proton sponge" effect, enhancing cytosolic delivery of therapeutics [24]. | Fusogenic, conical shape. |

This whitepaper explores the fundamental nanoscale phenomena governing biological interactions, focusing on the intertwined roles of surface area-to-volume (SA/V) ratio and quantum effects. The drastic increase in SA/V ratio at the nanoscale dominates physicochemical behaviors, influencing everything from cellular nutrient uptake to targeted drug delivery. Concurrently, quantum mechanical effects, including tunneling and spin phenomena, become significant in biological processes. This document provides a technical examination of these principles, details experimental methodologies for their investigation, and discusses their critical implications for diagnostic and therapeutic applications in medicine. The content is framed within the broader thesis that a quantitative understanding of these nanoscale fundamentals is essential for advancing biological research and developing next-generation biomedical technologies.

Operating at the scale of 1 to 100 nanometers, the nanoscale is the fundamental dimension of key biological machinery - including proteins, nucleic acids, and cellular organelles. At this scale, the classical physical rules that govern the macroscopic world begin to blend with the distinct laws of quantum mechanics. This confluence gives rise to unique phenomena that are not merely intermediate steps but represent entirely new physical and chemical states that dictate biological interactions.

Two principles are particularly critical: the surface area-to-volume (SA/V) ratio and the emergence of quantum effects. The SA/V ratio, a geometric property, becomes a dominant force at the nanoscale, making surface interactions more significant than bulk properties. This governs reactivity, adsorption, and the integration of nanomaterials with biological systems. Simultaneously, quantum mechanical phenomena such as quantum tunnelling, superposition, and entanglement are now understood to play potential roles in biological processes, from enzyme catalysis to sensory perception. The emerging field of quantum biology seeks to capture and understand these effects, despite the challenges of dissipation and decoherence posed by the warm, wet biological environment [29].

The goal of this whitepaper is to dissect these core principles, provide a framework for their experimental investigation, and contextualize their power in driving innovations across the biomedical landscape, from targeted drug delivery to advanced diagnostic imaging.

Core Principle I: Surface Area to Volume (SA/V) Ratio

Fundamental Impact and Biological Relevance

The surface area-to-volume ratio (SA/V) is a scaling principle that becomes profoundly important at the nanoscale. As a particle or structure decreases in size, its surface area decreases at a slower rate than its volume, resulting in a dramatic increase in the SA/V ratio. This geometric reality means that a vastly larger proportion of the material's atoms or molecules are located on the surface, ready to interact with the environment.

In biological systems, this principle is leveraged for efficiency. For instance, intestinal microvilli and the membrane folds in T-lymphocytes are macroscopic biological structures engineered to maximize surface area, thereby enhancing nutrient uptake and enabling cell deformation for migration, respectively [30]. At the nanoscale, this high SA/V ratio translates to enhanced reactivity, improved solubility, and greater ability to functionalize a material with targeting ligands, drugs, or imaging agents.

Quantitative Analysis of SA/V Scaling

The scaling relationship between surface area (SA) and volume (V) is quantified using the power law: ( SA = aV^b ), where ( b ) is the scaling factor (exponent) and ( a ) is a constant [30]. The value of ( b ) determines the nature of the scaling:

- ( b = 2/3 ) (Allometric/Geometric Scaling): This is the scaling observed in a perfect sphere, where the surface area increases at a slower rate than the volume. This leads to a decreasing SA/V ratio as size increases.

- ( b = 1 ) (Isometric Scaling): This indicates that surface area and volume grow at the same rate, resulting in a constant SA/V ratio across different sizes.

Contrary to the long-held assumption of ( \frac{2}{3} )-geometric scaling, recent single-cell studies on near-spherical mammalian cells (e.g., L1210, THP-1) have revealed that proliferating cells maintain a near-isometric scaling of plasma membrane components [30]. This means that as a cell grows, it maintains a nearly constant SA/V ratio, a feat achieved through increased plasma membrane folding in larger cells. This ensures sufficient plasma membrane area for critical functions like division and nutrient uptake across a wide range of cell sizes.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Scaling Factors (b) for Surface Area vs. Cell Size

| Cell Line / System | Scaling Factor (b) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Perfect Sphere | 0.667 | SA/V decreases with size |

| Surface-labeled Beads | 0.58 ± 0.01 | SA/V decreases with size [30] |

| L1210 Cells | 0.90 ± 0.02 | Near-isometric scaling (Nearly constant SA/V) [30] |

| THP-1 Cells | 1.01 ± 0.04 | Isometric scaling (Constant SA/V) [30] |

Functional Implications in Drug Delivery

The SA/V ratio is not merely an abstract geometric concept; it has direct, quantifiable impacts on drug delivery and absorption. Research on ketoconazole, a poorly water-soluble drug, has demonstrated that the efficacy of supersaturating drug delivery systems (SDDS) is highly dependent on the SA/V ratio of the experimental or physiological system [31].

The "parachute effect" provided by polymers like HPMC, which maintains drug supersaturation, has a diminishing impact on drug transport as the SA/V ratio increases. This is because at high SA/V ratios, permeation across the membrane becomes so rapid that drug precipitation is less of a limiting factor. This highlights a critical disconnect between in vitro models (with low SA/V ratios) and in vivo conditions.

Table 2: Surface Area to Volume (SA/V) Ratios in Various Experimental and Biological Systems

| System / Model | SA/V Ratio (cm⁻¹) | Context and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Closed System | 0.0 | Lacks absorption sink, overestimates precipitation potential [31] |

| Vertical Franz Diffusion Cell | 1.7 - 17 | Common in vitro permeation model [31] |

| Rat Intestine (in vivo) | 73.32 | Represents actual physiological condition; absorption is very rapid [31] |

Core Principle II: Quantum Effects in Biological Environments

Manifestations of Quantum Biology

At the nanoscale, the frontier of life science intersects with quantum physics. The emerging field of quantum life science investigates how quantum phenomena influence biological processes [29]. While these effects are often masked by decoherence in biological environments, they are increasingly recognized as vital to explaining certain physiological functions.

Key quantum effects with potential biological significance include:

- Quantum Tunneling: This effect allows particles to traverse energy barriers that would be insurmountable according to classical physics. It is crucial in enzyme catalysis, where protons and electrons can tunnel to drive biochemical reactions with high efficiency and specificity.

- Spin Coherence: The quantum property of electron spin is exploited in processes like avian magnetoreception, where it is hypothesized to enable birds to navigate using Earth's magnetic field.

- Entanglement and Superposition: While more speculative in biology, these quintessential quantum states are fundamental to the development of quantum sensors and quantum computing for biological simulation.

Investigation with Advanced Nano-Sensors

Capturing and quantifying these fragile quantum states in living systems is a formidable challenge. The field relies on advanced biological nano quantum sensors and other sophisticated technologies [29]. These tools are designed to measure quantum phenomena with high sensitivity and minimal disruption to the biological system.

Key investigative technologies include:

- Biological Nano Quantum Sensors: Nanoscale sensors, often based on defects in diamonds (NV centers), that can detect minute magnetic and electric fields, temperature, and strain at the quantum level within cells.

- Quantum Technology-Based Hyperpolarized MRI/NMR: This technique dramatically enhances the signal strength in magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy, enabling real-time tracking of metabolic processes and improving the detection of diseases like cancer at earlier stages.

- High-Speed 2D Electronic Spectrometers: These devices are used to study energy transfer dynamics, such as those in photosynthetic complexes, to identify signatures of long-lived quantum coherence.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Investigating SA/V Scaling in Single Cells

This protocol details the methodology for quantifying the size scaling of plasma membrane components, as described in the preprint on plasma membrane folding [30].

1. Principle: To measure the abundance of cell surface proteins as a proxy for cell surface area and correlate it with single-cell buoyant mass (a proxy for volume) to determine the scaling exponent ( b ).

2. Key Reagent Solutions:

- Suspended Microchannel Resonator (SMR): A cantilever-based instrument for high-precision measurement of single-cell buoyant mass [30].

- Cell Impermeable, Amine Reactive Dye: A fluorophore-coupled dye (e.g., NHS-ester dyes) that labels primary amines on extracellular proteins without crossing the plasma membrane.

- Alternative Labeling Chemistries: Maleimide compounds for labeling thiol groups on cell surface proteins, used for validation.

- Appropriate Cell Culture Media: For maintaining live suspension cell lines (e.g., L1210, BaF3, THP-1) during analysis.

3. Step-by-Step Workflow: 1. Cell Preparation: Harvest near-spherical mammalian suspension cells and keep them on ice to inhibit endocytosis. 2. Surface Labeling: Incubate cells with the amine-reactive fluorescent dye on ice for 10 minutes. Include control samples to validate surface-specificity via microscopy. 3. Exclusion of Dead Cells: Treat cells with a viability dye (e.g., propidium iodide) to exclude dead cells from the final analysis. 4. Coupled Measurement: Pass the labeled cell suspension through the SMR system integrated with a photomultiplier tube (PMT). This setup simultaneously measures the buoyant mass (size) and fluorescence intensity (surface protein content) of thousands of single cells. 5. Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence (proxy for SA) against buoyant mass (proxy for V) on a log-log scale. The slope of the resulting power-law fit is the scaling factor ( b ). A value of ~1 indicates isometric scaling.

Protocol: Functionalization of Nanomaterials for Targeted Delivery

A critical step in applying nanomaterials in medicine is functionalizing their surface to achieve targeted delivery and reduced immunogenicity.

1. Principle: To modify the surface of nanoparticles with functional groups, polymers, or biological ligands to control their interaction with biological systems.

2. Key Reagent Solutions:

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG): A polymer used to create a "stealth" coating, reducing opsonization and clearance by the immune system [32] [33].

- Targeting Ligands: Antibodies, folic acid, transferrin, or aptamers that bind specifically to receptors overexpressed on target cells (e.g., cancer cells) [34].

- Stimuli-Responsive Linkers: pH-sensitive or enzyme-cleavable bonds that ensure drug release is triggered specifically in the target microenvironment (e.g., tumor tissue) [34].

3. Step-by-Step Workflow: 1. Nanoparticle Synthesis: Synthesize the nanoparticle core (e.g., gold, iron oxide, polymeric) using top-down (e.g., milling) or bottom-up (e.g., chemical vapor deposition) methods [32] [33]. 2. Surface Activation: If necessary, activate the nanoparticle surface to create reactive groups (e.g., carboxyl, amine) for subsequent conjugation. 3. Ligand Conjugation: Covalently link the chosen functional molecules (e.g., PEG, folic acid) to the activated surface using appropriate crosslinker chemistry (e.g., EDC-NHS for carboxyl-amine coupling). 4. Purification and Characterization: Purify the functionalized nanoparticles from unreacted ligands using techniques like dialysis or centrifugation. Characterize the final product for size, surface charge (zeta potential), and conjugation efficiency [32]. 5. Validation: Test the targeting efficiency and stimulus-responsive release in vitro using relevant cell cultures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Nanoscale Biological Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Amine-Reactive Dyes (NHS-esters) | Labels primary amines on cell surface proteins for quantification of surface area. | Cell-impermeable; allows specific labeling of extracellular proteins [30]. |

| Suspended Microchannel Resonator (SMR) | Measures buoyant mass of single cells with high precision. | Provides a proxy for cell volume/dry mass; enables high-throughput correlation with fluorescence [30]. |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | Functionalization agent for nanoparticles to reduce immune recognition. | Creates a hydrophilic "cloud"; prolongs circulation half-life in vivo [32] [33]. |

| Targeting Ligands (e.g., Folic Acid) | Functionalization agent for active targeting of nanoparticles to diseased cells. | Binds to receptors overexpressed on target cells (e.g., folate receptor in cancer) [34]. |

| Quantum Dots | Nanoscale semiconductors used as fluorescent probes for bioimaging and biosensing. | Size-tunable emission; high photostability; ideal for tracking and multiplexed assays [32] [34]. |

| Iron Oxide Nanoparticles | Magnetic nanoparticles for use as MRI contrast agents or for magnetic hyperthermia. | Superparamagnetic; can be functionalized for targeting; responsive to external magnetic fields [33] [34]. |

Interrelationship and Biomedical Applications

The synergy between high SA/V ratio and quantum effects is the cornerstone of many modern nanomedical applications. A high SA/V ratio provides the platform for extensive functionalization and interaction, while quantum effects can be exploited for sensitive detection and novel therapeutic mechanisms.

A. Targeted Drug Delivery: Nanoparticles leverage their high SA/V ratio to carry large payloads of therapeutic agents. Their surface is functionalized with targeting ligands (active targeting) and PEG (stealth). The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect facilitates passive accumulation in tumor tissue. Once at the site, the unique tumor microenvironment (e.g., low pH, specific enzymes) can trigger drug release from stimuli-responsive nanocarriers [33] [34].

B. Advanced Diagnostics and Imaging: Quantum dots provide brilliant, stable fluorescence for multiplexed biomarker detection and cellular imaging [32]. Magnetic nanoparticles enhance contrast in MRI, allowing for the detection of previously occult small tumors [34]. The emerging field of quantum technology-based hyperpolarized MRI uses quantum principles to vastly amplify signal, enabling real-time metabolic imaging [29].

The unique phenomena arising at the nanoscale—specifically, the dominating influence of the surface area-to-volume ratio and the emergence of tangible quantum effects—form a fundamental pillar for understanding and innovating within biological environments. The ability to quantitatively measure SA/V scaling in cells and to functionalize nanomaterials based on this principle is now a standard, yet powerful, approach. Concurrently, the burgeoning field of quantum life science, equipped with nano quantum sensors and hyperpolarization techniques, is pushing the boundaries of what is measurable, offering a glimpse into the very quantum mechanical underpinnings of life processes.

Mastering these fundamentals is not an academic exercise; it is a prerequisite for the rational design of next-generation biomedical solutions. From overcoming biological barriers for drug delivery to achieving unprecedented sensitivity in diagnostics, the continued exploration of this unique physical realm promises to redefine the future of medicine and biological research.

Engineering Nano-Bio Interactions: Design Strategies for Targeted Therapeutics and Diagnostics

The systemic administration of nanoparticle-based therapeutics presents a fundamental challenge: the human body has evolved sophisticated mechanisms to recognize and eliminate foreign entities. Upon intravenous injection, nanoparticles are immediately confronted by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), which rapidly clears them from circulation, severely limiting their therapeutic potential [35]. This biological recognition is primarily mediated by the adsorption of blood proteins onto the nanoparticle surface, a process known as opsonization, which tags the particles for phagocytic removal [36]. Furthermore, for nanomedicines to treat diseases like cancer effectively, they must not only evade immune detection but also preferentially accumulate at disease sites and engage with specific cellular targets. Surface engineering addresses this dual challenge through two complementary strategies: PEGylation for stealth properties to prolong circulation, and ligand conjugation for active targeting to enhance specificity [35]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, methodologies, and evolving paradigms of these traditional yet critical surface modification techniques, framing them within the broader context of nanoscale biological interactions research.

The Stealth Effect: Fundamentals of PEGylation

Mechanism of Action and Conformational States

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) conjugation, or PEGylation, is a cornerstone technology for conferring "stealth" properties to nanoparticles. The stealth effect operates through two primary mechanisms: immune evasion by reducing protein adsorption and blocking MPS uptake, and reduced receptor-mediated clearance by organs like the liver [35]. PEG achieves this through its physicochemical properties. It is a highly flexible, hydrophilic polymer capable of forming extensive hydrogen bonds with water molecules. For instance, a single PEG2000 polymer can bind approximately 136 water molecules, effectively doubling its molecular weight through hydration [37]. This creates a dense, hydrophilic cloud around the nanoparticle that sterically hinders the approach and adsorption of opsonin proteins.

The protective efficacy of PEG is critically dependent on its surface density, which dictates its physical conformation [37]:

- Mushroom Regime: At low surface density, PEG chains adopt a coiled, mushroom-like conformation due to sufficient space for flexibility. This provides limited steric protection.

- Brush Regime: At high surface density, PEG chains are forced to extend away from the nanoparticle surface, forming a dense, brush-like layer. This conformation offers superior steric shielding and is more effective at minimizing protein adsorption.

Quantitative Impact on Pharmacokinetics

The beneficial effects of PEGylation on nanoparticle pharmacokinetics are well-documented. PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil/Caelyx) serves as an iconic clinical example, demonstrating dramatically prolonged circulation time and reduced cardiotoxicity compared to free doxorubicin [38]. The following table summarizes key quantitative data on how PEG properties influence nanoparticle behavior:

Table 1: Impact of PEG Properties on Nanoparticle Behavior and Pharmacokinetics

| PEG Property | Experimental Impact | Reference System |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Higher MW PEG (>10,000 Da) more effective at complement activation at high concentrations; ~2,000 Da common for nanocarriers. | [37] |

| Surface Density | Higher density shifts PEG to "brush" regime, enhancing stealth; quantified by equilibrium binding constant (KA) to proteins. | [35] |

| Lipid Anchor Length | DMG-PEG (C14) is "sheddable"; DSPE-PEG (C18) is more stable, enabling targeting. | [39] |

| PEG Ratio in Formulation | Low molar ratios (1.5-3%) improve stability; high ratios (10-20%) cause "PEG dilemma," reducing uptake. | [39] |

Active Targeting: Ligand Conjugation Strategies

While PEGylation provides passive stealth, active targeting involves the functionalization of nanoparticle surfaces with targeting ligands that recognize and bind to specific receptors overexpressed on target cells. This strategy aims to enhance cellular internalization and the specificity of therapeutic delivery.

The process of ligand conjugation often requires PEG derivatives that contain reactive terminal groups. A commonly used strategy involves azide-containing PEG lipids like DSPE-PEG-N3. This group allows for precise, bioorthogonal conjugation to targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies, or small molecules) that have been modified with a complementary cyclooctyne group (e.g., DBCO) via a copper-free strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) "click" reaction [39]. This method is favored for its efficiency and compatibility with biological systems.

The targeting ligands themselves are highly varied. In oncology, common targets include the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which is overexpressed in many solid tumors. Functionalizing nanoparticles with EGFR-targeting ligands has been shown to restore transfection efficiency in EGFR-positive cell lines in a ligand-specific manner, effectively overcoming the shielding effects of the PEG layer [39]. The success of active targeting is influenced by the density of the ligand and the surface chemistry of the nanoparticle, which must be optimized to ensure the ligand remains accessible and functional despite the presence of the stealth coating [35].

The PEG Dilemma and Emerging Alternatives

Limitations of Conventional PEGylation

Despite its widespread use, traditional PEGylation faces significant drawbacks, collectively known as the "PEG dilemma" [39] [35]. This refers to the trade-off where the PEG corona that provides steric shielding also creates a physical barrier that can hinder cellular uptake and endosomal escape, ultimately reducing the therapeutic efficacy of the encapsulated drug [39]. Furthermore, repeated administration of PEGylated nanoparticles can induce anti-PEG antibodies (IgM and IgG), leading to an Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) phenomenon upon subsequent doses and potential hypersensitivity reactions [35] [37]. These immunogenic responses are a growing concern for the long-term viability of PEGylated therapeutics.

Next-Generation Surface Engineering Strategies

To address the limitations of PEG, several advanced surface modulation strategies are being developed:

- Sheddable PEG Coatings: These systems use linkers that are stable in circulation but cleaved in response to specific tumor microenvironment stimuli (e.g., low pH, specific enzymes). This allows the nanoparticle to shed its PEG layer upon reaching the target site, reconciling the conflict between long circulation and efficient cellular uptake [35].

- Alternative Polymer Coatings: Researchers are exploring non-PEG hydrophilic polymers such as poly(2-oxazoline) (pOx) and polysarcosine (pSar). These polymers offer similar stealth properties with a potentially lower risk of inducing immunogenic responses [38].

- Zwitterionic Coatings: Surfaces modified with zwitterionic molecules, which contain both positive and negative charges, can form a super-hydrophilic layer that resists protein fouling through a strong hydration effect, presenting another promising alternative to PEG [38].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Engineering and Characterization

Protocol 1: Formulation of PEGylated mRNA Polyplexes

This protocol details the non-covalent incorporation of PEG-lipids into mRNA complexes based on research by [39].

Materials:

- Cationic Carrier: Lipo-amino fatty acid modified xenopeptide (LAF-XP).

- mRNA: CleanCap FLuc mRNA (5moU).

- PEG Lipids: DMG-PEG (2 kDa) or DSPE-PEG-N3 (2 kDa).

- Buffer: Aqueous buffer (e.g., 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4).

Procedure:

- Prepare separate solutions of the LAF-XP carrier and PEG lipid in ethanol or a compatible organic solvent.

- Mix the LAF-XP and PEG lipid solutions at the desired molar ratio (e.g., 1.5%, 3%, 10% PEG lipid).

- Dilute the lipid mixture into a rapidly stirring aqueous buffer to form pre-inserted PEG-lipid micelles or bilayers.

- Add the mRNA solution to the lipid mixture at a predetermined nitrogen-to-phosphate (N:P) ratio to complex the RNA and form the final polyplexes.

- Incubate the mixture for 30 minutes at room temperature to allow for complete complexation.

Characterization: