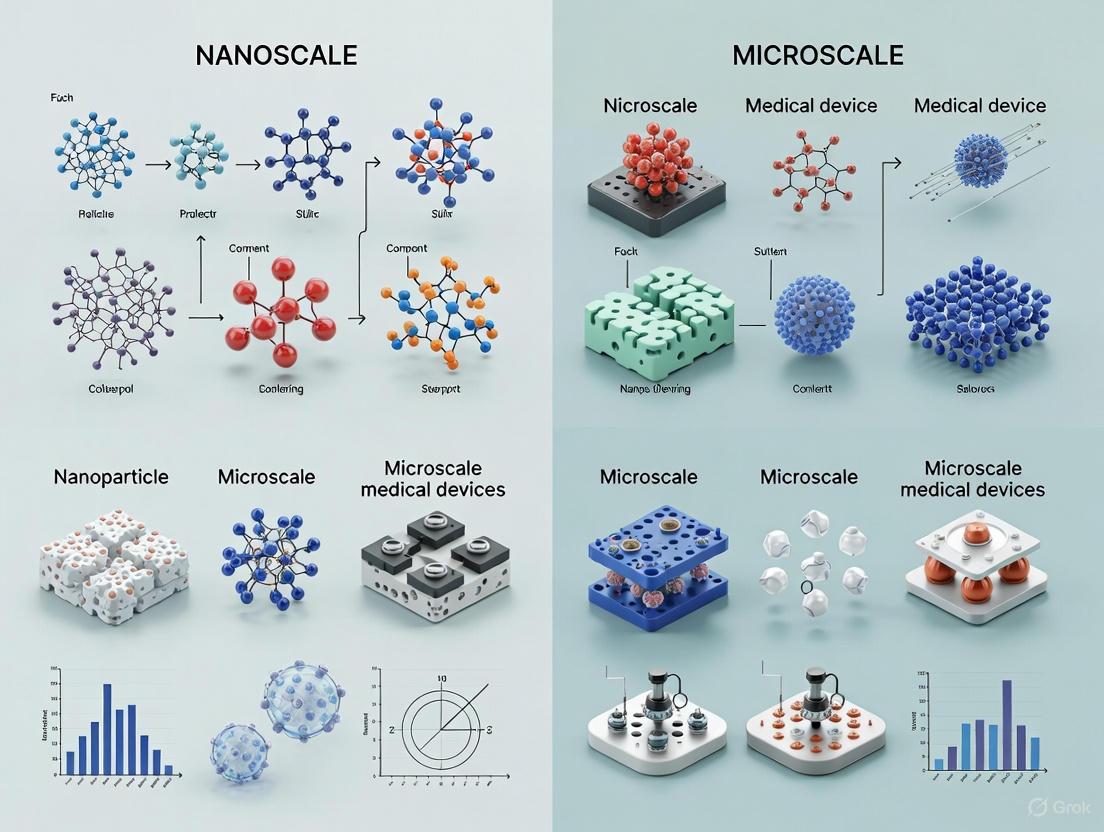

Nanoscale vs. Microscale Medical Devices: A Comparative Analysis for Next-Generation Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of nanoscale and microscale medical devices, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Nanoscale vs. Microscale Medical Devices: A Comparative Analysis for Next-Generation Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of nanoscale and microscale medical devices, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles and unique physicochemical properties that differentiate these device classes. The review details advanced fabrication methodologies, material choices, and their specific applications in targeted drug delivery, advanced diagnostics, and regenerative medicine. It further addresses critical challenges in biocompatibility, manufacturing, and regulatory navigation while offering optimization strategies. Finally, the article presents a rigorous comparative validation of performance characteristics, synthesizing key takeaways to outline future trajectories and clinical implications for the field of precision medicine.

Defining the Scale: Fundamental Principles and Properties of Micro and Nano Medical Devices

The evolution of miniaturized electromechanical systems has catalyzed revolutionary advances across numerous scientific and industrial domains, particularly in medicine and biotechnology. At the heart of this technological revolution lie two interconnected yet distinct fields: Micro-Electromechanical Systems (MEMS) and Nano-Electromechanical Systems (NEMS). These systems represent the integration of mechanical elements, sensors, actuators, and electronics on a common substrate through microfabrication technology, distinguished primarily by their dimensional scale and the physical phenomena they exploit [1]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the precise classification boundaries between MEMS and NEMS is not merely academic—it directly influences device design, material selection, fabrication methodologies, and ultimately, functional performance in biomedical applications.

This comparison guide establishes a structured framework for classifying MEMS and NEMS technologies based on dimensional parameters, material properties, transduction mechanisms, and functional capabilities. The ability to accurately categorize these systems enables more informed decisions in developing next-generation medical devices, diagnostic tools, and targeted therapeutic platforms. As the healthcare landscape increasingly embraces precision medicine, the distinction between microscale and nanoscale technologies becomes paramount in designing solutions that can operate effectively within the complex physiological environment of the human body [2] [1].

Dimensional Classification Criteria

Primary Size Parameters

The most fundamental distinction between MEMS and NEMS resides in their characteristic physical dimensions. While a straightforward size threshold provides an initial classification framework, the complete dimensional profile encompasses multiple parameters that collectively determine device categorization and functional potential.

Table 1: Dimensional Parameters for MEMS and NEMS Classification

| Parameter | MEMS Range | NEMS Range | Measurement Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic Device Size | 1 mm - 100 nm [2] | 100 nm - 1 nm [2] | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) |

| Layer Thickness | 1-100 μm | 1-100 nm | Profilometry, Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) |

| Feature Resolution | 1-10 μm | 1-100 nm | Optical & Electron Microscopy |

| Surface Area to Volume Ratio | Moderate | Very High | Calculated from dimensional analysis |

The dimensional transition from MEMS to NEMS is not merely a continuation of scaling laws but represents a fundamental shift in operational principles. While MEMS devices typically function with characteristic sizes spanning from 1 millimeter down to 100 nanometers, NEMS devices operate at scales ranging from 100 nanometers down to 1 nanometer [2]. This dimensional crossover approximately at 100 nanometers is significant because it marks the scale where quantum mechanical effects may begin to influence device behavior, and surface area-to-volume ratios increase dramatically, enhancing surface-dominated phenomena crucial for sensing applications [2] [3].

Material Composition Profiles

The selection of materials for MEMS and NEMS fabrication is dictated by both functional requirements and constraints imposed by the dimensional scale. Each material class offers distinct advantages that can be leveraged for specific application domains, particularly in biomedical implementations.

Table 2: Material Composition in MEMS and NEMS

| Material Class | MEMS Applications | NEMS Applications | Key Biomedical Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon & Derivatives | Structural components, substrates [2] | Limited due to fabrication complexity | Excellent mechanical properties, CMOS compatibility |

| Polymers (PDMS, Polyimide) | Flexible substrates, microfluidics [2] | Drug delivery carriers, responsive matrices [4] | Biocompatibility, flexibility, cost-effectiveness |

| Metals (Au, Ni, Al) | Electrodes, interconnects, thermal elements [2] | Functional nanoparticles, contrast agents | Electrical conductivity, corrosion resistance |

| Piezoelectrics (PZT, AlN) | Inertial sensors, ultrasonic transducers [2] | High-frequency resonators, energy harvesters | Direct energy conversion, precise actuation |

| 2D Materials (Graphene) | Limited use in conventional MEMS | Membranes, sensors, nanochannels [3] | Atomic thickness, exceptional strength, high sensitivity |

Material diversity increases as systems transition from conventional MEMS to NEMS platforms. Traditional MEMS have extensively utilized silicon due to its excellent mechanical properties and compatibility with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) processing technology [2]. Polymers such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and polyimide are widely employed in biomedical MEMS for their biocompatibility and flexibility, making them ideal for wearable devices and lab-on-a-chip applications [2]. In contrast, NEMS increasingly leverage two-dimensional materials like graphene, which at approximately 0.335 nanometers thick represents the ultimate limit of material thickness while offering exceptional mechanical strength, chemical stability, and exceptional electrical conductivity [3]. These material characteristics enable NEMS devices with unprecedented sensitivity for detecting molecular-level interactions, a capability less pronounced in their microscale counterparts.

Fabrication Techniques and Experimental Protocols

MEMS Fabrication Methodologies

The manufacturing paradigm for MEMS predominantly relies on techniques adapted from the semiconductor industry, with modifications to accommodate three-dimensional mechanical structures and diverse material sets. The experimental workflow typically involves sequential additive and subtractive processes performed on substrate wafers.

Protocol: Surface Micromachining for MEMS

Objective: Fabricate a freestanding polysilicon micromirror structure for optical sensing applications.

Materials and Reagents:

- Substrate: Silicon wafer (4-inch diameter, <100> orientation)

- Sacrificial Layer: Phosphosilicate Glass (PSG), 2.0 μm thickness

- Structural Layer: Low-pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD) polysilicon, 2.5 μm thickness

- Etchant: Buffered oxide etch (BOE, 6:1 ratio HF:NH₄F) for release

- Photoresist: AZ-5214E image reversal photoresist

- Etch Mask: Silicon nitride (Si₃N₄, 500 Å) deposited via plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD)

Experimental Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean silicon wafer using standard RCA-1 and RCA-2 protocols to remove organic and ionic contaminants.

- Sacrificial Layer Deposition: Deposit PSG layer via PECVD at 350°C to a thickness of 2.0 μm.

- Photolithographic Patterning:

- Dehydrate wafer at 200°C for 30 minutes

- Spin-coat photoresist at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds (resulting thickness ~1.4 μm)

- Soft bake at 95°C for 60 seconds

- Expose through mask #1 (anchor pattern) with UV light at 365 nm, dose 140 mJ/cm²

- Develop in AZ-400K (1:4 dilution) for 60 seconds

- Anchor Etching: Transfer pattern to PSG layer using BOE with etch rate of 100 nm/min, followed by resist stripping in acetone and isopropanol.

- Structural Layer Deposition: Deposit LPCVD polysilicon at 580°C using silane precursor, followed by doping via phosphorus diffusion at 950°C for 30 minutes.

- Structural Layer Patterning:

- Repeat photolithography using mask #2 (mirror pattern)

- Etch polysilicon in SF₆-based plasma etch (rate 300 nm/min)

- Release Etch: Immerse structure in BOE for 45 minutes to remove sacrificial PSG layer, followed by critical point drying with CO₂ to prevent stiction.

Validation Metrics: Measure resonant frequency using laser Doppler vibrometry (expected range: 10-50 kHz); characterize surface flatness via interferometry (<λ/10 deviation).

NEMS Fabrication Methodologies

NEMS fabrication presents significantly greater challenges due to nanoscale feature requirements, often necessitating either advanced lithographic techniques or bottom-up assembly approaches. The experimental protocols frequently combine conventional microfabrication with specialized nanofabrication processes.

Protocol: Graphene NEMS Resonator Fabrication

Objective: Realize a graphene-based nanoelectromechanical resonator for mass sensing applications.

Materials and Reagents:

- Graphene Source: CVD-grown monolayer graphene on copper foil (commercial source)

- Substrate: Silicon wafer with 300 nm thermal oxide

- Transfer Medium: Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA, 495 kDa molecular weight)

- Etchants: Ammonium persulfate (0.1 M aqueous solution for copper etching), deionized water rinses

- Electrode Materials: Electron-beam evaporated chromium (5 nm adhesion layer) and gold (50 nm)

- Lithography: Hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ, XR-1541) negative tone electron-beam resist

Experimental Procedure:

- Graphene Transfer:

- Spin-coat PMMA on graphene/copper at 3000 rpm (thickness ~300 nm)

- Cure at 150°C for 1 minute

- Etch copper backing in ammonium persulfate for 4 hours at room temperature

- Transfer PMMA/graphene stack to target substrate

- Remove PMMA in acetone vapor (60°C) for 2 hours followed by 10-minute immersion in fresh acetone

- Electrode Patterning:

- Pattern alignment marks using electron-beam lithography (EBL) with HSQ resist

- Develop in 25% tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) for 1 minute

- Evaporate Cr/Au (5 nm/50 nm) and lift-off in Remover 1165 at 80°C

- Graphene Delineation:

- Pattern graphene mesa structures using EBL with HSQ as an etch mask

- Reactive ion etch graphene in O₂/Ar plasma (10 sccm/40 sccm, 100 W, 30 seconds)

- Release Process:

- Create suspension by etching underlying oxide in vapor HF for 3 minutes

- Critical point drying to prevent collapse of suspended structures

Validation Metrics: Confirm monolayer graphene quality via Raman spectroscopy (G/D peak ratio >5, symmetric 2D peak); verify suspension via AFM; measure resonance frequency using laser interferometry (expected range: 10-100 MHz).

Figure 1: NEMS Fabrication Workflow for Graphene Devices

Transduction Mechanisms and Performance Metrics

Comparative Transduction Principles

The fundamental operational principles of MEMS and NEMS devices vary significantly due to scale-dependent physical phenomena. These transduction mechanisms determine how devices interact with their environment, convert signals, and ultimately perform their intended functions in biomedical applications.

Table 3: Transduction Mechanisms in MEMS and NEMS

| Transduction Mechanism | MEMS Implementation | NEMS Implementation | Biomedical Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piezoresistive | Silicon strain gauges [1] | Graphene piezoresistors [3] | Pressure sensors, tactile sensing |

| Capacitive | Parallel-plate sensing [1] | Nanogap capacitive sensing | Accelerometers, displacement sensors |

| Piezoelectric | PZT thin films [2] | ZnO nanowires | Energy harvesting, ultrasonic transducers |

| Optical | Micromirrors, interferometry [1] | Photonic crystals, plasmonics | Biosensors, imaging systems |

| Resonant | Silicon cantilevers (kHz-MHz) | Graphene resonators (MHz-GHz) [3] | Mass sensing, molecular detection |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The scaling effects from micro- to nanoscale manifest as dramatic improvements in key performance metrics, particularly sensitivity, response time, and power consumption. These enhancements enable new capabilities in medical diagnostics and monitoring.

Table 4: Performance Metrics for Biomedical Sensing Applications

| Performance Metric | Typical MEMS Performance | Typical NEMS Performance | Measurement Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Sensitivity | ~10⁻¹² g [2] | ~10⁻²¹ g [3] | Controlled mass loading with calibrated particles |

| Power Consumption | μW-mW range | pW-nW range | Direct current measurement with source meter |

| Resonant Frequency | kHz-MHz range | MHz-GHz range [3] | Laser Doppler vibrometry or electrical readout |

| Scale Factor Stability | 10-100 ppm/°C | 1-10 ppm/°C | Environmental chamber testing (-40°C to +85°C) |

| Quality Factor (Q) in Air | 10-100 | 100-10,000 [3] | Ring-down measurement of resonant peak |

The exceptional properties of two-dimensional materials like graphene substantially enhance NEMS transducer capabilities. Graphene exhibits a pronounced piezoresistive effect with gauge factors typically ranging from 1.9 to 8.8 for chemical vapor deposition (CVD) graphene, enabling highly sensitive strain detection [3]. Furthermore, when configured as resonant structures, graphene NEMS can achieve quality factors (Q) exceeding 10,000 in vacuum conditions, significantly higher than most comparable MEMS resonators [3]. This combination of high sensitivity and exceptional resonance characteristics enables NEMS devices to detect mass changes at the zeptogram (10⁻²¹ grams) scale, sufficient for identifying individual molecules or molecular interactions—a capability with profound implications for molecular diagnostics and drug discovery [2] [3].

Biomedical Applications: Comparative Analysis

Diagnostic and Monitoring Applications

The dimensional and performance characteristics of MEMS and NEMS directly influence their suitability for specific biomedical applications, with each domain offering distinct advantages depending on diagnostic requirements and physiological constraints.

Table 5: Medical Diagnostic and Monitoring Applications

| Application Domain | MEMS Solutions | NEMS Solutions | Key Differentiating Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lab-on-a-Chip Diagnostics | Microfluidic channels, pumps, valves [2] | Nanofluidic channels for single biomolecule analysis | Sample volume requirements, resolution |

| Implantable Sensors | Glucose monitors, intracranial pressure sensors [1] | Cellular-level monitors, neural probes | Size constraints, biocompatibility challenges |

| Medical Imaging | Ultrasound transducers, optical coherence tomography [2] | Enhanced contrast agents, molecular imaging | Resolution limits, penetration depth |

| Point-of-Care Diagnostics | Portable blood analyzers, sweat sensors | Single-molecule detection chips | Sensitivity requirements, cost considerations |

| Wearable Health Monitors | Activity trackers, continuous glucose monitors [1] | Epidermal electronics, smart contact lenses | Form factor, power consumption |

Therapeutic and Surgical Applications

Beyond diagnostics, MEMS and NEMS technologies enable increasingly sophisticated therapeutic interventions, from targeted drug delivery to minimally invasive surgical procedures, each leveraging scale-specific advantages.

Table 6: Therapeutic and Surgical Applications

| Application Domain | MEMS Solutions | NEMS Solutions | Clinical Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Drug Delivery | Implantable microreservoirs with valves [2] | Nanoparticle-based delivery systems [5] | Specificity of targeting, dosing control |

| Surgical Robotics | Micromechanical instruments, force feedback [4] | Nanoscale end-effectors, cellular manipulation | Precision, minimal tissue damage |

| Tissue Engineering | Scaffolds with micro-scale features | Nanofiber scaffolds with biochemical signaling | Biomimetic architecture, cellular integration |

| Neuromodulation | Microelectrode arrays for neural stimulation | Nanowire-based neural interfaces [4] | Resolution, long-term stability |

| Minimally Invasive Surgery | Endoscopic tools, capsules | Cellular-level surgery, nanoscale manipulation [5] | Recovery time, procedural precision |

The application of hydrogel-based micro/nano-robotic medical devices exemplifies the convergence of MEMS and NEMS principles for therapeutic purposes. These devices feature three-dimensional crosslinked networks integrated with responsive chemical functional groups, enabling them to undergo structural and functional transitions under various external stimuli, including chemical energy, temperature, light, pH, ultrasound, magnetic fields, and ions [4]. Such multi-actuation synergistic strategies combine the physical orientation capability of magnetic nanoparticles with photothermal materials like gold nanoparticles, allowing for precise regulation of hydrogel network structure and drug release kinetics with potential targeting accuracy at the cellular level [4]. This "external navigation combined with internal response" design represents a sophisticated approach that transcends traditional scale boundaries in medical devices.

Figure 2: Multi-Actuation Mechanism in Biomedical Nano/Micro Devices

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The experimental protocols for developing and characterizing MEMS and NEMS devices require specialized materials and reagents that enable precise fabrication and functionalization. The following toolkit represents essential resources for researchers working in this interdisciplinary field.

Table 7: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MEMS/NEMS Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Suppliers | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SU-8 Photoresist | High-aspect-ratio MEMS structures | Kayaku Advanced Materials | Requires optimized UV exposure and post-bake |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Microfluidics, flexible substrates | Dow Silicones | Base:curing agent 10:1 ratio, degas before use |

| CVD Graphene | NEMS resonators, sensors | Graphenea, Beijing Graphene Institute | PMMA-assisted transfer, avoid tearing |

| HSQ XR-1541 | Negative tone e-beam resist for NEMS | Dow Silicones | Sensitive to environmental contamination |

| Buffered Oxide Etch (BOE) | Silicon oxide etching for release | Sigma-Aldrich, KMG Chemicals | Teflon containers, precise timing critical |

| Tetramethylammonium Hydroxide (TMAH) | Silicon anisotropic etching | Sigma-Aldrich | 25% concentration, 80°C for <100> Si etch |

| Parylene C | Biocompatible conformal coating | Specialty Coating Systems | CVD deposition, excellent barrier properties |

The classification of micro- and nano-electromechanical systems according to dimensional boundaries reveals a sophisticated technological ecosystem where scale dictates application potential. MEMS devices, with their characteristic dimensions spanning from 1 millimeter down to 100 nanometers, provide robust platforms for medical monitoring, implantable sensors, and microfluidic diagnostic systems [2]. In contrast, NEMS devices, operating at scales from 100 nanometers down to 1 nanometer, offer unprecedented sensitivity for molecular detection, targeted therapeutic delivery, and cellular-level interventions [2] [3].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this dimensional classification provides a strategic framework for technology selection based on application requirements. MEMS technologies offer maturity, reliability, and integration capabilities well-suited for physiological monitoring, diagnostic platforms, and therapeutic delivery systems where microscale interactions are sufficient [1]. Meanwhile, NEMS platforms, though less mature in their development pipeline, enable fundamentally new capabilities in precision medicine through their ability to interact with biological systems at molecular scales, offering potential breakthroughs in early disease detection, highly targeted therapeutic interventions, and fundamental biological research [3] [5].

The ongoing convergence of MEMS and NEMS technologies with advanced materials, artificial intelligence, and wireless connectivity heralds a new era in biomedical devices that will progressively blur these dimensional boundaries [1]. As the field advances, the most impactful innovations will likely emerge from strategic applications of both microscale and nanoscale principles to create integrated systems that leverage the unique advantages of each domain, ultimately enabling more precise, personalized, and effective healthcare solutions.

The evolution of medical devices is intrinsically linked to advancements in materials science, particularly at micro- and nanoscales. Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) combine mechanical elements, sensors, actuators, and electronics on a common silicon substrate through microfabrication, with characteristic sizes from 1 mm to 100 nm [2]. Scaling down further to Nano-Electro-Mechanical Systems (NEMS), within the 100 nm to 1 nm range, offers greater sensitivity and new functionalities for biomedical applications [2]. The choice of material—silicon, polymers, metals, or piezoelectrics—fundamentally dictates a device's performance, biocompatibility, and integration potential within the human body. This guide objectively compares these material families, providing researchers and drug development professionals with critical data and methodologies to inform the design of next-generation medical devices.

Material Performance Comparison

Critical Properties at a Glance

The selection of a base material is a foundational decision in device design. The following table provides a quantitative comparison of key properties across the four material families.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Key Materials in Medical Device Fabrication

| Material Family | Example Materials | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations | Common Fabrication Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon | Single-crystal silicon (SCS), Silicon Carbide (SiC) | ~130-185 (SCS) [2] | Superior mechanical properties, CMOS compatibility, high precision [2] | Brittleness, heat sensitivity [2] | Photolithography, bulk/surface micromachining [2] |

| Polymers | PDMS, Polyimide, SU-8, Parylene C | 0.00057-3 (PDMS) [2] | Biocompatibility, flexibility, low cost, ease of processing [2] | Low thermal stability, challenging dimensional control [2] | Additive manufacturing, soft lithography, deposition [2] |

| Metals | Gold, Nickel, Aluminum, Ni-Cu alloys | ~70 (Au), ~200 (Ni) [2] | Excellent electrical conductivity, durability, corrosion resistance (Au) [2] | Can be heavy, potential cytotoxicity (Ni) | Electrodeposition, sputtering, ICP etching [2] |

| Piezoelectrics | PZT, PVDF, AlN, BaTiO₃ | ~63 (PZT ceramic) [6] | Self-powering (energy harvesting), precise actuation, high sensitivity sensing [2] [6] | Brittleness (ceramics), lower output (polymers), lead toxicity (PZT) [6] [7] | Screen printing, sol-gel, 3D printing, thin-film deposition [6] [7] |

Application-Based Performance Analysis

Material performance must be evaluated in the context of specific applications. The following analysis is based on demonstrated use cases in peer-reviewed literature and commercial reports.

Table 2: Application-Oriented Performance of Material Families

| Application | Superior Material Family | Experimental Performance Data | Comparative Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Precision Sensors/Actuators | Silicon & Piezoelectrics | Piezoresistive Si sensors: ΔR/R = πσ (π: piezoresistive coeff.) [1]. Capacitive MEMS: C = εA/d for inertial measurement [1]. | Silicon excels in miniaturized, on-chip integration. Piezoelectrics offer direct energy conversion (sensing/actuation) with high frequency response [2]. |

| Wearable/Flexible Devices | Polymers & Polymer-based Piezoelectrics | PVDF & its copolymers: Flexible, biocompatible, lower piezoelectric coefficient (d₃₃) than PZT but sufficient for wearables [6]. | Polymers (e.g., PDMS) provide substrate flexibility and comfort. PVDF enables mechanical energy harvesting from body movements [1] [6]. |

| Biocompatible Implants | Specific Polymers & Metals | Gold: Corrosion-resistant, biocompatible for biomedical sensors [2]. Polyimide: Biocompatible, used in flexible electronics and lab-on-a-chip [2]. | Gold is ideal for chronic implants requiring stable interfaces. Polymers like polyimide and PLLA offer flexibility and long-term biostability [2] [6]. |

| Energy Harvesting | Piezoelectrics | PZT: High piezoelectric coeff., but rigid [6]. 3D-printed flexible piezoelectrics: Convert multi-directional stress to energy [7]. | Ceramics (PZT) offer high power density. Emerging flexible/organic materials (PVDF, PLLA) enable harvesting from soft, dynamic tissues [6] [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Material Evaluation

Protocol 1: Piezoresistive Sensing Characterization

Objective: To quantify the sensitivity and linearity of a piezoresistive material (e.g., silicon) by measuring its change in electrical resistance under applied mechanical strain [1].

Materials & Reagents:

- Piezoresistive Cantilever: A silicon-based microfabricated beam with integrated strain gauge.

- Precision Micropositioning System: To apply controlled deflection.

- Source Meter Unit (SMU): To measure electrical resistance (e.g., Keithely 2400).

- Wheatstone Bridge Circuit: For high-sensitivity resistance measurement [1].

- Vibration Isolation Table: To minimize external noise.

Methodology:

- Setup: Mount the piezoresistive cantilever firmly at one end. Connect the strain gauge to the Wheatstone bridge circuit and SMU.

- Calibration: Zero the measurement by balancing the Wheatstone bridge with no applied force.

- Application of Strain: Use the micropositioner to deflect the free end of the cantilever in controlled increments. The induced stress (σ) and strain (ε) cause deformation in the sensing element.

- Data Acquisition: At each deflection step, record the change in electrical resistance (ΔR) via the SMU. The fundamental relationship is ΔR/R = πσ, where π is the piezoresistive coefficient and R is the baseline resistance [1].

- Analysis: Plot the applied strain (ε) against the normalized resistance change (ΔR/R). The slope of the linear region provides the Gauge Factor (GF = (ΔR/R)/ε), a key metric of sensitivity.

Protocol 2: Piezoelectric Energy Harvesting Output Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the voltage and power output of a piezoelectric material in an energy harvesting configuration for powering low-energy devices [6] [7].

Materials & Reagents:

- Piezoelectric Device: A defined sample (e.g., PZT ceramic disc, flexible PVDF film).

- Electrodynamic Shaker: To simulate controlled, cyclic mechanical vibrations.

- Oscilloscope: To measure the open-circuit output voltage (V₀₀).

- Variable Load Resistor Box: To determine power output across different loads.

- Laser Vibrometer: To precisely measure the input mechanical displacement/acceleration.

Methodology:

- Setup: Fix the piezoelectric sample to the shaker. Connect its electrodes to the oscilloscope and the resistor box in parallel.

- Input Calibration: Activate the shaker at a fixed frequency and amplitude. Use the vibrometer to confirm the input mechanical conditions.

- Open-Circuit Measurement: Under steady-state vibration, measure the peak-to-peak open-circuit voltage (V₀₀) on the oscilloscope.

- Power Optimization: Connect the variable load resistor. For a range of resistance values (Rₗₗ), measure the root-mean-square voltage (Vᵣₘₛ) across the resistor. Calculate output power for each point using P = Vᵣₘₛ² / Rₗₗ.

- Analysis: Plot power (P) versus load resistance (Rₗₗ). The peak of this curve indicates the matched load impedance and maximum power output (Pₘₐₓ) of the harvester. The piezoelectric charge coefficient d can be inferred from the relationship between input stress and generated charge [6].

Research Reagent Solutions: The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Device Fabrication and Testing

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Fabrication of flexible substrates, microfluidic channels, and wearable devices [2]. | Biocompatible, elastomeric, transparent, gas-permeable. |

| Lead Zirconate Titanate (PZT) | High-performance actuators, sensors, and ultrasonic transducers [2] [7]. | High piezoelectric coefficient, but contains lead (toxic). |

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) | Flexible piezoelectric sensors and energy harvesters for wearable applications [6]. | Biocompatible polymer, flexible, lower piezoelectric output than PZT. |

| SU-8 Epoxy Resist | Creates high-aspect-ratio microstructures for MEMS and microfluidics [2]. | Negative-tone photoresist, highly cross-linked, chemically resistant. |

| Gold Sputtering Target | Deposition of biocompatible electrodes and conductive traces for implants [2]. | High conductivity, excellent corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility. |

| Silicon-on-Insulator (SOI) Wafers | Base substrate for fabricating high-precision, monolithic MEMS sensors and actuators [2]. | Provides a single-crystal silicon device layer, ideal for complex micromachining. |

Visualizing Material Selection and Experimental Workflows

Decision Pathway for Material Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting a material family based on primary device requirements, helping researchers navigate the initial design phase.

Diagram 1: A decision pathway for selecting a core material family based on key device requirements.

Piezoresistive Sensor Characterization Workflow

This diagram details the experimental workflow for characterizing a piezoresistive sensor, as described in Protocol 1.

Diagram 2: Step-by-step workflow for the piezoresistive sensor characterization protocol.

In the evolving landscape of medical technology, the distinction between microscale and nanoscale devices is foundational, driving paradigm shifts in diagnostic, therapeutic, and regenerative medicine. Micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) are typically characterized by dimensions spanning from 1 millimeter down to 100 nanometers, integrating electrical and mechanical components for patient monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment [8]. In contrast, nano-electromechanical systems (NEMS) and nanomaterials operate on a scale of 100 nanometers down to 1 nanometer, a realm where fundamental material properties become dominated by surface and quantum phenomena rather than bulk composition [8] [9]. This comparison guide objectively analyzes how these distinct physicochemical properties—specifically surface area-to-volume ratio, quantum effects, and chemical reactivity—govern the performance, application, and regulatory considerations of medical devices at these different scales, providing researchers with critical data for technology selection and development.

Comparative Analysis of Fundamental Properties

The transition from the micro- to the nanoscale precipitates a fundamental shift in material behavior. These changes are not merely geometric but represent alterations in the very physical laws governing the materials, with direct implications for their performance in medical devices.

Surface Area-to-Volume Ratio

The surface area-to-volume ratio (SA:V) exhibits a non-linear increase as material dimensions decrease, following an inverse power law [10]. This relationship is the primary driver behind many of the unique properties observed at the nanoscale.

- Nanoscale Behavior: At dimensions below 100 nm, the SA:V ratio increases dramatically [11] [10]. This means a significantly larger proportion of the material's atoms or molecules are positioned on the surface rather than in the interior. In biomedical applications, this vast surface area enables more extensive interactions with biological entities, such as proteins, cells, and tissues, which is critical for enhancing drug loading capacity in delivery systems, improving catalytic efficiency in diagnostic assays, and accelerating tissue integration in implants [11].

- Microscale Behavior: MEMS devices, with characteristic dimensions from 100 nm to 1 mm, possess a considerably lower SA:V ratio compared to their nanoscale counterparts [8]. While this reduces their intrinsic chemical reactivity, it provides superior structural integrity for mechanical components such as microgears, cantilevers, and membranes used in sensors and actuators [8].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Scale on Surface-Dominated Properties

| Property | Nanoscale Devices & Materials | Microscale Devices (MEMS) |

|---|---|---|

| SA:V Ratio Trend | Very high; increases exponentially with decreasing size [11] [10] | Moderate; scales inversely with size [8] |

| Impact on Drug Loading | High capacity for therapeutic conjugation and encapsulation due to extensive surface [11] | Limited primarily to micro-reservoirs in drug delivery systems [8] |

| Structural Role | Often requires scaffolding or composite integration for macroscopic stability [11] | Provides primary structural components (e.g., silicon cantilevers, gears) [8] |

| Catalytic Efficiency | Exceptional due to high density of active surface sites [10] | Not a primary function; surfaces often serve as passive platforms |

Quantum Confinement and Optical Effects

Quantum mechanical effects become pronounced when material dimensions approach the de Broglie wavelength of electrons, typically in the low nanometer range. This leads to size-tunable properties not found in microscale materials or bulk solids.

- Nanoscale Quantum Phenomena: Semiconductor nanocrystals, known as quantum dots (QDs), exhibit a direct relationship between their physical size and their optoelectronic properties due to the quantum confinement effect [12] [10]. As the size of the QD decreases, the energy band gap increases, resulting in a shift of both absorption and emission spectra to higher energies (a blue shift) [12]. This allows researchers to "fine-tune" the photoluminescence emission of QDs from the UV to the infrared simply by controlling their size during synthesis [12] [10]. For instance, CdSe QDs can emit across the 450-650 nm range, while CdTe QDs can extend into the near-infrared (500-750 nm), which is crucial for deep-tissue imaging [12].

- Microscale Optical Properties: The optical properties of materials used in MEMS, such as silicon, polymers, and metals, are inherently bulk properties. They are determined by the material's composition and crystal structure but cannot be precisely tuned by varying the device's physical dimensions [8]. Their applications in devices are typically structural or electronic (e.g., waveguides, reflectors) rather than active luminescent probes.

Figure 1: Quantum Confinement Mechanism leading to size-tunable optical properties in nanoscale semiconductors, a phenomenon absent in microscale devices and bulk materials.

Table 2: Experimental Optical Data for Size-Tunable Quantum Dots

| Quantum Dot Core | Size Range (nm) | Emission Wavelength Range (nm) | Key Application in Medical Devices |

|---|---|---|---|

| CdSe | 2 - 6 | 450 - 650 [12] | Multiplexed bioimaging and biosensing [12] |

| CdTe | 2.5 - 7 | 500 - 750 [12] | Deep-tissue imaging (NIR-I window) [12] |

| InP/ZnS | ~3 - 6 | 530 - 650 [12] | Heavy-metal-free bioimaging [12] |

| CdSe/ZnS (Core/Shell) | 3 - 7 | 520 - 670 [12] | Enhanced brightness and stability for diagnostics [12] |

Chemical Reactivity and Catalytic Activity

The dramatic increase in surface energy and the presence of coordinatively unsaturated surface atoms make nanomaterials significantly more reactive than microscale materials of the same composition.

- Nanoscale Reactivity: The high density of surface atoms acts as active sites for chemical reactions, dramatically enhancing catalytic efficiency and chemical reactivity [11] [10]. A prime example is silver, where nanoparticles exhibit potent antimicrobial properties not seen in bulk silver due to this increased reactivity [9]. This property is exploited in wound dressings and coatings for medical devices to prevent infection. Furthermore, the melting point of nanocrystals is dramatically lowered, and their solubility is greatly enhanced compared to bulk materials [10].

- Microscale Reactivity: The chemical reactivity of microscale materials is substantially lower and aligns more closely with bulk material behavior [8]. While surface treatments (e.g., plasma activation, chemical etching) can enhance reactivity for specific applications like bonding or adhesion, the intrinsic catalytic potential is minimal compared to nanomaterials. MEMS devices primarily rely on their mechanical and electrical properties rather than their chemical reactivity for function [8].

Experimental Protocols for Property Characterization

Protocol: Quantifying Surface Area via BET Analysis

The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method is the gold standard for determining the specific surface area of porous and nanoscale materials.

- Sample Preparation: Pre-treat the nanomaterial (e.g., quantum dots, metal nanoparticles) or microscale powder by degassing under vacuum at an elevated temperature (e.g., 150°C for 2 hours) to remove adsorbed contaminants and moisture [12].

- Gas Adsorption: Cool the sample to cryogenic temperature (typically liquid N₂ at 77 K). Under controlled conditions, expose the sample to incremental doses of an inert adsorbate gas, usually nitrogen (N₂), and measure the quantity of gas adsorbed at each relative pressure (P/P₀) [10].

- Data Analysis: Apply the BET equation to the adsorption data within the relative pressure range of 0.05-0.30 P/P₀. The linearized form of the equation is used to calculate the monolayer volume (V_m) of adsorbed gas.

- Surface Area Calculation: The specific surface area (SBET) is calculated using the formula: ( S{BET} = \frac{Vm N A{cs}}{V0 m} ), where ( N ) is Avogadro's number, ( A{cs} ) is the cross-sectional area of the adsorbate molecule (0.162 nm² for N₂), ( V_0 ) is the molar volume of gas, and ( m ) is the mass of the sample. Expected outcomes show nanomaterials like mesoporous silica nanoparticles can exhibit surface areas >500 m²/g, vastly exceeding those of microscale particles [10].

Protocol: Measuring Quantum Confinement via UV-Vis Spectroscopy

This protocol characterizes the size-dependent optical absorption of semiconductor quantum dots.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare dilute colloidal solutions of the quantum dots (e.g., CdSe, CdTe) in a transparent solvent (e.g., toluene or water, depending on surface functionalization) [12]. For comparison, prepare a suspension of a microscale semiconductor powder (e.g., bulk CdS).

- Instrumentation Setup: Use a UV-Vis spectrophotometer with a wavelength range of at least 300-800 nm. Employ quartz cuvettes for optimal UV transmission.

- Data Acquisition: Record the absorption spectrum of each sample. For quantum dot samples of varying sizes, the absorption onset will show a clear blue shift as the particle size decreases.

- Bandgap Calculation: The Tauc plot method is used to determine the optical bandgap (E_g). Plot (αhν)² versus photon energy (hν), where α is the absorption coefficient. Extrapolate the linear region of the plot to the x-axis; the intercept provides the direct bandgap energy. Experimental data will confirm a direct correlation between decreasing QD size and increasing bandgap energy [12] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and testing of micro- and nanoscale medical devices rely on specialized materials and reagents.

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Device Research

| Material/Reagent | Core Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Quantum Dots (CdSe, CdTe, InP) | Fluorescent probes with size-tunable emission and high photostability [12]. | Intracellular tracking, in vivo deep-tissue imaging, and diagnostic assays [12]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | A biocompatible, flexible polymer with high gas permeability and easy molding [8]. | Flexible substrates, microfluidic channels, and membranes in biomedical MEMS devices [8]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles & Nanorods | Biocompatible plasmonic materials for enhanced imaging, photothermal therapy, and biosensing [13] [9]. | Contrast agents, LSPR biosensors, and photothermal ablation of tumor cells [13] [9]. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | A coordinating solvent and surface ligand in the high-temperature synthesis of quantum dots [12]. | Prevents aggregation and controls growth during QD synthesis, passivating surface defects [12]. |

| Methyl Viologen | An electrochromic reporter molecule that changes color upon reduction [13]. | Optical readout in closed bipolar electrochemistry (CBE) diagnostic sensors [13]. |

| Lead Zirconate Titanate (PZT) | A piezoelectric material that generates charge under mechanical stress and vice versa [8]. | Precision actuators, energy harvesters, and ultrasonic transducers in MEMS devices [8]. |

Performance Comparison in Medical Applications

The distinct properties of micro- and nanoscale materials dictate their suitability for specific medical applications, with implications for sensitivity, therapeutic efficacy, and regulatory pathways.

- Diagnostic Sensitivity: Nanoscale devices leveraging localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) in gold nanoparticles or the intense fluorescence of quantum dots offer exceptional sensitivity for detecting low-abundance biomarkers, enabling early-stage disease diagnosis [13] [12]. For example, LSPR sensors transduce subtle changes in the local dielectric environment (e.g., from biomarker binding) into a measurable shift in resonance wavelength ((\Delta\lambda)) [13]. MEMS-based sensors, while highly precise for measuring physical parameters like pressure or flow, generally lack this molecular-level sensitivity unless integrated with nanoscale recognition elements [8].

- Therapeutic Precision: Nanoscale systems enable targeted drug delivery with superior precision. They exploit the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect of tumor vasculature for passive targeting and can be functionalized with ligands (e.g., antibodies, folic acid) for active targeting to specific cells [14]. This minimizes systemic toxicity and increases therapeutic efficacy. Microscale devices, such as implantable drug pumps, excel at delivering larger, localized volumes of therapeutics but cannot achieve this degree of cellular or sub-cellular targeting [8].

- Regulatory and Safety Considerations: The high reactivity and unique properties of nanomaterials necessitate stringent safety evaluations. The European Medical Device Regulation (MDR) classifies devices containing or consisting of nanomaterials as Class III (highest risk) by default, unless it can be demonstrated that the potential for internal exposure is low or negligible [15]. This is due to concerns about nanoparticle uptake, potential for organ accumulation, and induction of oxidative stress or inflammation [15] [14]. The toxicological assessment of nanostructured medical devices is particularly challenging, as traditional testing methods (e.g., device extracts) may not be representative, requiring evaluation of the nanomaterials themselves [15].

Figure 2: A decision pathway for researchers selecting between nanoscale and microscale platforms based on the primary goal of their medical device project.

The comparative analysis unequivocally demonstrates that the physicochemical properties of materials are fundamentally different at the micro- and nanoscale, leading to distinct and often complementary roles in medical devices. Nanoscale materials offer unparalleled advantages in applications demanding high surface reactivity, quantum-enabled optical tunability, and intimate interaction with biological systems for targeted diagnostics and therapy. Conversely, microscale devices provide the robust, structurally sound platforms necessary for mechanical actuation, fluid handling, and system integration. The future of medical device innovation lies in the convergent integration of these platforms, harnessing the unique strengths of each scale to create next-generation devices that are smarter, more effective, and minimally invasive. Researchers must navigate this landscape with a clear understanding of both the immense potential and the heightened regulatory and safety considerations, particularly for nanoscale constructs.

The fields of nanoscale and microscale devices are driving unprecedented innovation in modern medicine. Micro-electromechanical Systems (MEMS) typically feature components between 1 millimeter and 100 nanometers, integrating mechanical elements, sensors, actuators, and electronics on a single silicon chip. [2] In contrast, nanoscale devices operate at the 1 to 100 nanometer range, exploiting unique quantum and surface area effects that emerge at this scale. [16] This distinction is not merely dimensional; it fundamentally dictates device physics, fabrication methodologies, and ultimate biological applications. Microfluidic systems, which manipulate microliter to picoliter fluid volumes within channels narrower than a millimeter, serve as a crucial bridge between these domains, enabling the precise control necessary for both microscale analysis and nanoscale therapeutic delivery. [17]

The convergence of these technologies is creating a new paradigm in medical science. Miniaturization provides benefits including high precision, quick response times, and low production costs, while nanoscale phenomena enable novel targeting mechanisms and material properties not possible at larger scales. [2] This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these device categories, examining their respective performances, experimental validations, and specialized applications in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Device Categories

Table 1: Performance comparison of key microfluidic device types

| Device Type | Typical Feature Size | Throughput Capacity | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous-Flow Microfluidics | 10-500 µm | Moderate | Simple design, established fabrication | Limited parallelization, laminar flow dominance | Chemical synthesis, basic bioassays [17] |

| Droplet Microfluidics | 1-100 µm (droplet diameter) | Very High (<1000 droplets/sec) | Extreme parallelization, isolated microreactors | Complex control systems, potential coalescence | Single-cell analysis, digital PCR, high-throughput screening [17] [18] |

| Digital Microfluidics (DMF) | 100-1000 µm (electrode pitch) | High | Programmable, no pumps required, individual droplet control | Limited volume range, electrode complexity | Point-of-care diagnostics, automated sample preparation [17] [18] |

| Paper-Based Microfluidics | 10-500 µm (channel width) | Low | Ultra-low cost, capillary-driven flow, disposable | Limited fluid control, higher result variability | Low-cost diagnostics, environmental sensing [17] [18] |

Table 2: Performance comparison of nanoscale vs microscale biomedical devices

| Performance Characteristic | Nanoscale Devices | Microscale Devices (MEMS) | Comparative Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 1-100 nm | 100 nm - 1 mm | Nanoscale quantum dots provide superior resolution for intracellular imaging compared to microscale optical sensors [16] |

| Targeting Precision | Subcellular (e.g., nuclear targeting) [19] | Cellular to tissue level [2] | NLS-functionalized nanocarriers achieve 5.8x higher nuclear delivery compared to non-targeted versions [19] |

| Drug Delivery Efficiency | ~0.7% average tumor accumulation [19] | N/A (primarily diagnostic) | Despite targeting, nanocarriers still show low overall accumulation, highlighting delivery challenges [19] |

| Magnetic Field Sensitivity | N/A | 0.83 µT/Hz (MEMS Lorentz force sensor) [20] | MEMS magnetic sensors achieve high sensitivity without magnetic materials, avoiding hysteresis [20] |

| Power Consumption | Minimal for passive targeting | 19.5-43 mW (MEMS sensor/actuator) [20] | Smart MEMS devices can tune power consumption based on operational mode (sensing vs. actuation) [20] |

| Fabrication Complexity | High (molecular assembly) | Moderate (CMOS-compatible processes) [2] | Silicon MEMS leverages established semiconductor manufacturing [2] |

| Therapeutic Payload Capacity | Variable (5-20% loading efficiency for many nanocarriers) [21] | N/A (primarily diagnostic) | Liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles show superior drug loading compared to dendrimers and inorganic nanoparticles [21] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

MEMS Sensor Performance Validation

Objective: Characterize the performance of a bi-axial Lorentz force MEMS magnetometer as both a sensor and actuator. [20]

Materials and Reagents:

- SOIMUMPs fabricated device: Structural layer of single-crystal silicon (2 µm), with patterned electrodes. [20]

- Electrothermal actuation system: DC voltage sources for thermal tuning (electrodes A-G). [20]

- Capacitive sensing setup: AC-DC voltage source (VDC + VAC = 35 V) for resonant drive (electrode H). [20]

- External magnetic field source: Capable of generating fields up to ±400 mT. [20]

- Laser Doppler vibrometer: For non-contact displacement measurement. [20]

Methodology:

- Device Characterization: Measure the native resonance frequency of the clamped-guided curved microbeam using the electrostatic actuator (electrode H) and laser vibrometer. [20]

- Electrothermal Tuning: Apply specific DC voltage combinations (detailed as "tuning cases") to the V-shaped and straight beam actuators to induce controlled axial stress in the microbeam, thereby shifting its resonance frequency. [20]

- Magnetic Sensing Mode: At 19.5 mW input power, expose the device to varying magnetic fields (±400 mT). Measure the resultant resonance frequency shift caused by Lorentz force interaction, calculating sensitivity as ~36.58% T⁻¹. [20]

- Actuator Mode: At 43 mW input power, demonstrate the device's magnetic-field-insensitive operation, achieving ~4 µm displacement with significantly reduced magnetic sensitivity (3.28% T⁻¹). [20]

- Linearity Assessment: Plot resonance frequency shift versus applied magnetic field strength to establish linear response across the measured range. [20]

Nanocarrier Targeting Efficiency Evaluation

Objective: Quantify the nuclear targeting efficiency of ligand-functionalized nanocarriers. [19]

Materials and Reagents:

- Nuclear-targeted nanocarriers: Liposomes or polymeric nanoparticles conjugated with Nuclear Localization Signals (NLS). [19]

- Control nanocarriers: Non-functionalized particles.

- Cell culture model: Appropriate cancer cell lines (e.g., HeLa, MCF-7).

- Fluorescent therapeutic cargo: Doxorubicin or model DNA plasmids tagged with fluorophores (e.g., FITC).

- Confocal microscopy setup: With image analysis software.

- Flow cytometer: For quantitative cellular uptake analysis.

Methodology:

- Nanocarrier Formulation: Prepare NLS-conjugated nanocarriers using standard bioconjugation techniques, encapsulating fluorescent cargo. Prepare identical but non-functionalized control particles. [19]

- Cell Treatment: Incubate cells with targeted and control nanocarriers at equal concentrations (e.g., 100 µg/mL) for predetermined time points (2, 4, 8 hours). [19]

- Subcellular Localization Analysis:

- Fix cells at each time point and stain nuclei with DAPI.

- Image using confocal microscopy, collecting Z-stacks to verify intra-nuclear localization.

- Quantify fluorescence co-localization of the cargo (FITC) with nuclear stains (DAPI) using specialized software.

- Uptake and Efficacy Quantification:

- Analyze cellular uptake via flow cytometry.

- Compare nuclear delivery efficiency by calculating the ratio of nuclear fluorescence in targeted versus control groups.

- Report results as fold-increase (e.g., "NLS-functionalized carriers demonstrated 5.8x higher nuclear delivery"). [19]

Diagram 1: Nuclear targeting assay workflow for evaluating nanocarrier efficiency.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for device development and evaluation

| Reagent/Material | Category | Primary Function | Research Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Microscale Material | Flexible substrate for microfluidics, biocompatible encapsulation | Organ-on-chip devices, wearable sensors, flexible MEMS [2] [17] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Nanoscale Material | Surface functionalization to reduce immune clearance ("PEGylation") | Improving nanocarrier circulation time, reducing protein adsorption [19] [21] |

| Nuclear Localization Signals (NLS) | Nanoscale Targeting Ligand | Active targeting to cell nucleus via importin-mediated transport | Nuclear-targeted drug and gene delivery systems [19] |

| Single-Crystal Silicon (SCS) | Microscale Material | Structural component for high-precision MEMS | Sensors, actuators, resonators in biomedical MEMS [2] |

| Lead Zirconate Titanate (PZT) | Microscale Material | Piezoelectric transduction for sensing/actuation | MEMS energy harvesters, ultrasonic transducers, accelerometers [2] |

| Phospholipids & Cholesterol | Nanoscale Material | Liposome formation for drug encapsulation | Biocompatible nanocarriers for therapeutic delivery [19] [21] |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Nanoscale Material | Biodegradable polymer for controlled drug release | Sustained-release drug delivery systems [19] |

| SU-8 & Polyimide | Microscale Material | Structural polymers for micromachining | MEMS sensors, microfluidic channel fabrication [2] |

Diagram 2: Material selection logic for micro/nano device fabrication.

The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that the choice between nanoscale and microscale devices is fundamentally application-dependent. Microscale MEMS devices offer superior performance in physical sensing applications requiring precise mechanical transduction, with proven capabilities in magnetic field detection (0.83 µT/Hz sensitivity) and tunable multi-functionality as both sensors and actuators. [20] Conversely, nanoscale delivery systems provide unprecedented access to subcellular compartments, enabling therapeutic interventions at the molecular level through sophisticated targeting strategies like NLS conjugation. [19]

Emerging hybrid approaches that integrate both technologies show particular promise for future biomedical innovations. Microfluidic platforms naturally serve as integration frameworks, housing both MEMS sensors for environmental monitoring and nanocarriers for targeted therapeutic delivery. [17] [18] The growing integration of artificial intelligence with both nano- and micro-devices is further enhancing their analytical capabilities, enabling real-time data processing and adaptive functionality at the point of use. [22] [18] For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic selection of device scale must consider the specific biological target, required spatial resolution, and the physical principles best suited to address the scientific question or clinical need at hand.

From Fabrication to Function: Manufacturing Techniques and Breakthrough Applications

Advanced manufacturing technologies are revolutionizing the development of medical devices, enabling new capabilities at both the micro- and nanoscales. This guide provides an objective comparison of three pivotal technologies—additive manufacturing, laser welding, and microfluidic fabrication—within the context of medical research, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental data, and specific applications for drug development and biomedical science.

The design and manufacturing of devices at micro- and nanoscales offer significant advantages for medical applications, including high precision, rapid response times, and low production costs [2]. Micro-electromechanical Systems (MEMS) and Nano-electromechanical Systems (NEMS) represent the forefront of this miniaturization, with characteristic sizes spanning from 1 millimeter down to 1 nanometer [2].

Table: Fundamental Characteristics and Applications by Scale

| Feature | Microscale Devices | Nanoscale Devices |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic Size | 1 mm - 100 nm [2] | 100 nm - 1 nm [2] |

| Key Manufacturing Technologies | Additive Manufacturing (FDM, SLS), Laser Welding, Microfluidic Fabrication (Hot Embossing, 3D Printing) [23] [17] | Nanomaterial Synthesis, 2D Material Fabrication, advanced BioMEMS [2] |

| Dominant Materials | Polymers (PDMS, Polyimide), Silicon, Metals (Nickel, Gold), PZT [2] | Two-dimensional materials (Graphene), nanomaterials, advanced composites [2] |

| Primary Medical Applications | Surgical guides, implant prototypes, drug delivery pumps, lab-on-a-chip diagnostics [24] [17] | Targeted drug delivery systems, advanced biosensors, nanoscale actuators [2] |

| Key Advantages | Easier to fabricate and integrate, established regulatory pathways, versatile material options [2] [25] | Enhanced sensitivity, access to unique physical phenomena, superior mechanical properties [2] |

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Additive Manufacturing in Medtech

Additive manufacturing (AM), or 3D printing, builds objects layer-by-layer directly from digital models, enabling complex geometries with minimal waste [23]. Its application has significantly expanded from prototyping to creating end-use parts in the medical field [24].

Table: Comparison of Key Additive Manufacturing Technologies

| Technology | Typical Materials | Tensile Strength Range | Dimensional Accuracy | Best-Suited Medical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | Thermoplastics (PLA, ABS, TPU) [23] | 20-60 MPa [23] | ±0.5% (lower limit ±0.5 mm) [23] | Low-cost prototypes, educational models, non-sterile surgical guides [23] |

| Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) | Nylon (PA 12, PA 11), TPU [26] | 40-50 MPa [26] | ±0.3% (lower limit ±0.3 mm) [26] | Biocompatible components, surgical guides, complex ducting [26] |

| Multi-Laser Metal Printing | Titanium alloys, Cobalt-Chrome [27] | 900-1050 MPa (post-HIP) [27] | ±0.1% (lower limit ±0.1 mm) [27] | Fatigue-sensitive orthopedic implants (spine, joints) [27] |

| Electron Beam Melting (EBM) | Titanium alloys [27] | ~900 MPa [27] | ±0.2% (lower limit ±0.2 mm) [27] | Porous bone-integrating structures for implants [27] |

Key Performance Findings:

- Strength Gap: While AM can meet cast and wrought titanium specs, forging remains approximately 20-30% stronger. Advanced Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) cycles are being used to close this gap by improving fatigue strength and enhancing mechanical properties [27].

- Production Speed: Multi-laser systems are accelerating build times, dramatically reducing the cost per part and opening the door to new medical applications [27].

- Innovation in Metal AM: GE's Point Melt technology for EBM melts metal powder through small points instead of lines, enabling support-free production of complex geometries like porous structures, which maximizes build chamber utilization [27].

Laser Welding for Medical Devices

Laser welding provides a non-contact, high-precision joining method essential for medical devices that require cleanliness and water tightness, such as endoscopic surgical tools [28].

Table: Laser Welding Performance Specifications

| Performance Metric | Typical Specification/Data | Comparison to Traditional Methods (Adhesives/Mechanical Fasteners) |

|---|---|---|

| Weld Seam Width | < 0.2 mm [28] | Significantly narrower and more controlled. |

| Positioning Accuracy | ±0.005 mm [28] | Far superior, enabled by servo-controlled axes. |

| Water Tightness | Excellent, required for endoscopic devices [28] | Superior, as it eliminates potential leakage points from seals or adhesives. |

| Chemical Contamination | None (no adhesives) [28] | Eliminates risk of chemical contamination from bonding agents. |

| Process Monitoring | Real-time via CCD camera [28] | Enables immediate quality checks and adjustments, unlike most traditional methods. |

Microfluidic Fabrication

Microfluidics manipulates small volumes of fluids in micrometer-scale channels, forming the basis for lab-on-a-chip devices, point-of-care diagnostics, and organ-on-chip research [17]. The global market is projected to grow from USD 22.78 billion in 2024 to between USD 73.85 billion and USD 110.40 billion by the early 2030s [25] [29].

Table: Microfluidic Device Fabrication Methods and Performance

| Fabrication Method | Typical Materials | Feature Resolution | Throughput & Scalability | Primary Application Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft Lithography (PDMS) | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [17] | ~1 µm [17] | Low to medium; excellent for prototyping [17] | R&D, academic labs, proof-of-concept [17] |

| Hot Embossing | Thermoplastics (PMMA, PC) [25] [17] | ~10 µm [25] | High; suited for mass production [25] | Industrial-scale replication [25] |

| 3D Printing | Photopolymers, Flexdym [17] | ~50 µm [17] | Medium; rapid prototyping, custom geometries [17] | Prototyping, complex custom devices [17] |

| Injection Molding | Polymers (PS, PP) [25] | ~10-25 µm [25] | Very high; cost-effective at large volumes [25] | Mass production of commercial devices [25] |

Key Performance Findings:

- Material Shift: Polymers dominate the market due to lower cost and faster fabrication compared to silicon and glass. PDMS is widely used for prototyping, though its hydrophobic nature and potential for swelling can be limitations [2] [29].

- Market Drivers: The largest application segment is In-Vitro Diagnostics (IVD), accounting for over 50% of the market, driven by the rising demand for point-of-care testing [29].

- Integration Trends: A major trend is the integration of microfluidics with sensors, electronics, and AI to create more functional and automated devices [25] [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Evaluating Fatigue Strength of 3D-Printed Orthopedic Implants

Objective: To assess and improve the fatigue performance of a titanium spinal implant manufactured via Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) to meet or exceed wrought titanium specifications [27].

Materials and Reagents:

- Titanium Ti-6Al-4V ELI powder: The raw material for printing, chosen for its high strength-to-weight ratio and biocompatibility.

- Isopropyl Alcohol: Used for post-print cleaning to remove loose powder from the implant's surface and internal channels.

- Inert Gas (Argon): Provides an inert atmosphere during the printing process to prevent oxidation of the molten metal.

- HIP Vessel: The equipment used for post-processing to reduce internal porosity and enhance material density.

Methodology:

- Printing: Manufacture the implant on a multi-laser LPBF system under an argon atmosphere. Key parameters include laser power, scan speed, and layer thickness.

- Post-Processing:

- Stress Relief: Thermally treat the part to relieve internal stresses from the rapid cooling during printing.

- Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP): Subject the implant to a defined HIP cycle (e.g., 900-1000°C under 1000+ bar argon pressure). The specific time-temperature-pressure profile is fine-tuned to maximize fatigue strength without forming a detrimental "alpha case" surface layer [27].

- Finish Machining: CNC machine critical interfaces to final dimensional tolerances.

- Testing: Subject the finished implant to cyclic loading in a simulated physiological environment (e.g., in saline at 37°C) per ASTM F1800 standards. The number of cycles to failure is recorded and compared to the minimum requirement for wrought titanium spinal implants.

Protocol: Validating Hermetic Seal of a Laser-Welded Implantable Pump

Objective: To verify the watertight integrity of a laser-welded seam on a miniature implantable drug delivery pump [28].

Materials and Reagents:

- Fiber Laser Welding System: Equipped with a high-precision rotary table and CCD visual positioning.

- Test Fluid (DI Water): A safe medium for leak testing; may be substituted with ethanol for dye-penetration tests.

- Pressure Gauge and Regulator: To apply and monitor precise internal pressure to the device.

- CCD Camera System: For real-time monitoring of the weld process and post-weld inspection.

Methodology:

- Fixture Setup: Mount the pump housing and lid in the laser welder's pneumatic chuck, ensuring coaxial alignment accuracy within ±0.005 mm [28].

- Welding: Execute the weld using pre-programmed CNC code. Parameters include a weld seam width of <0.2 mm, with the laser welder head automatically adjusting to the part's contour.

- In-Process Monitoring: The integrated CCD camera monitors the weld pool in real time to detect any instability or defects.

- Hermeticity Testing:

- Pressure Decay Test: Pressurize the welded device with air, submerge it in water, and monitor for bubbles.

- Dye Penetration Test: Apply a colored dye to the weld seam, then wipe clean and examine for any dye that has penetrated through microscopic cracks.

Protocol: Fabricating and Testing a PDMS Organ-on-a-Chip

Objective: To create a microfluidic device for culturing human liver cells under dynamic flow conditions to model drug metabolism [17].

Diagram Title: Organ-on-a-Chip Fabrication and Use Workflow

Materials and Reagents:

- PDMS Sylgard 184: A silicone elastomer kit used to create the transparent, gas-permeable microfluidic chip.

- Silicon Wafer: Serves as the master mold for patterning the microchannels.

- SU-8 Photoresist: A negative photoresist used to create the high-resolution channel patterns on the silicon wafer master.

- Oxygen Plasma Cleaner: Used to activate the PDMS and glass surfaces for irreversible bonding.

- Extracellular Matrix (e.g., Collagen): Coats the internal channels of the chip to promote cell attachment and growth.

- Human Hepatocytes: The primary liver cells used to populate the chip and model liver function.

Methodology:

- Master Fabrication: Create a silicon wafer master with the negative relief of the desired microchannels using standard photolithography with SU-8 photoresist [2] [17].

- PDMS Molding: Mix the PDMS base and curing agent (typically 10:1 ratio), pour over the master, and cure at 65°C for 2-4 hours [17].

- Device Assembly: Peel the cured PDMS off the master, punch inlet/outlet ports, and bond irreversibly to a glass slide using oxygen plasma treatment [17].

- Cell Culture: Sterilize the device, coat the main channel with collagen, and seed human liver cells into the channel. Allow cells to adhere.

- Drug Testing: Connect the chip to a peristaltic pump to create dynamic flow conditions. Introduce the drug candidate into the flow medium and collect outflow for mass spectrometry analysis to measure metabolic products.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Materials and Reagents for Advanced Medical Device Manufacturing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Sylgard 184) | Fabrication of microfluidic devices and organ-on-chip models [2] [17] | Biocompatible, transparent, gas-permeable, flexible; enables rapid prototyping. |

| Ti-6Al-4V ELI Powder | Raw material for 3D printing of orthopedic and cranial implants [27] | High strength-to-weight ratio, excellent biocompatibility, corrosion resistance. |

| PA 12 (Nylon 12) Powder | Material for Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) of biocompatible components [26] | Biocompatible, sterilizable, well-documented evidence for regulatory submissions. |

| SU-8 Photoresist | Creating high-aspect-ratio microstructures for MEMS and microfluidic masters [2] | High resolution, chemical resistance; forms the template for PDMS devices. |

| PZT (Lead Zirconate Titanate) | Fabrication of piezoelectric sensors, actuators, and energy harvesters in MEMS [2] | High piezoelectric coefficient, enables conversion of mechanical energy to electrical signals. |

| Medical-Grade PEEK Filament | FDM printing of patient-specific surgical guides and implants [23] | High mechanical strength, radiolucency, excellent chemical and wear resistance. |

| Polyimide | Structural material for flexible electronics and sensors in BioMEMS [2] | High chemical and thermal resilience, excellent mechanical properties. |

The ability to engineer materials at the nanoscale (1-100 nm) has revolutionized numerous scientific fields, particularly medical device research and drug development. The synthesis of nanomaterials is predominantly achieved through two fundamental philosophical approaches: top-down and bottom-up [30] [31]. The choice between these methods is a critical initial decision for researchers, as it directly influences the nanomaterial's physical properties, chemical behavior, and ultimate suitability for specific biomedical applications, such as targeted drug delivery, diagnostic imaging, or implantable devices [30] [32].

In the context of medical device development, this comparison is especially pertinent. Nanoscale devices often exhibit properties vastly different from their microscale counterparts due to increased surface area-to-volume ratios and quantum effects that emerge at the nanoscale [33] [32]. These unique characteristics can lead to enhanced biocompatibility, improved drug loading efficiency, and novel diagnostic capabilities not achievable with microscale materials. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two synthesis pathways to inform the experimental design of researchers and scientists in the field.

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Top-Down Approach: Sculpting from Bulk

The top-down approach involves the mechanical, chemical, or physical breakdown of bulk materials into nanostructures [31] [34]. This method can be likened to a sculptor carving a statue from a large block of marble—it begins with a larger entity and reduces it to the desired nanoscale form. The focus is on creating nanostructures through the reduction of dimensionality.

Key Experimental Protocols for Top-Down Synthesis:

- Mechanical Milling: This technique uses a planetary ball mill where a powder of the bulk material is placed in a chamber with grinding balls. The process relies on the energy transfer from the rotating or vibrating balls to the powder. Key parameters include rotating speed, ball size and quantity, ball-to-powder mass ratio, milling duration, and environment [34]. The shear forces generated during grinding fracture the particles down to the nanoscale.

- Laser Ablation: In this physical method, a high-energy laser beam is focused onto a solid target in a liquid or gas environment. At low laser flux, the absorbed energy heats the material, causing it to evaporate or sublimate. At high flux, the material is instantly converted to a plasma, which upon cooling, condenses into nanoparticles [34].

- Chemical Etching: This multi-step process begins with coating a bulk metal with a masking material (e.g., wax) to protect areas that should not be etched. The masked sample is then submerged in a chemical etchant, which selectively breaks down the molecular bonds in the exposed areas, leading to the formation of nanostructures [34].

- Sputtering: This vacuum-based process involves introducing an inert gas (e.g., Argon) into a chamber, which is then ionized and accelerated by an electric field. The resulting positively charged ions strike a solid target material, dislodging atoms. These vaporized atoms travel and deposit onto a substrate, forming a thin nanoscale film [34].

Bottom-Up Approach: Building from Atoms

In contrast, the bottom-up approach constructs nanomaterials from atomic or molecular precursors via chemical reactions or self-assembly [31] [34]. This philosophy mimics natural processes like DNA replication or protein formation, where complexity emerges from the assembly of simpler building blocks [31]. This approach emphasizes precise control over the fundamental building blocks to create the final nanostructure.

Key Experimental Protocols for Bottom-Up Synthesis:

- Sol-Gel Method: This multi-step chemical process begins with a precursor (often metal alkoxides) dissolved in a solvent to create a colloidal suspension (sol). Hydrolysis and condensation reactions then form a gel-like network. The gel is subsequently dried, often using supercritical drying to prevent collapse of the nanostructure, to produce a solid nanopowder or aerogel [34].

- Chemical Precipitation: This method involves preparing a precursor solution containing metal ions. A precipitating agent (e.g., a reducing agent) is then added, initiating a chemical reaction that causes the metal ions to form solid nanoparticles that precipitate out of the solution. The nanoparticles are separated via centrifugation or filtration and washed to remove impurities [34].

- Microwave-Assisted Synthesis: This technique places the precursor solution in a microwave reactor. The microwaves energize the molecules in the solution, causing rapid and uniform heating. This localized heating initiates and accelerates the nucleation and growth of nanoparticles, allowing for precise control over reaction kinetics [34].

- Self-Assembly: This process relies on the spontaneous organization of nanoparticles into ordered structures or patterns, driven by intermolecular forces such as van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, or hydrophobic effects [31] [34]. Nanoparticles are dispersed in a liquid, where they interact and arrange themselves based on their intrinsic properties, much like magnets sticking together.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows and logical relationships of these two synthesis approaches:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The selection between top-down and bottom-up approaches has profound implications for the characteristics and performance of the resulting nanomaterials. The table below provides a structured, quantitative comparison based on key parameters critical for medical device and drug development applications.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Synthesis Approaches

| Comparison Parameter | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Breaking down bulk materials into nanostructures [31] [34] | Building nanostructures from atoms or molecules [31] [34] |

| Key Techniques | Mechanical milling, Laser ablation, Chemical etching, Sputtering [34] | Sol-gel, Chemical precipitation, Self-assembly, Microwave-assisted synthesis [34] |

| Scalability & Cost | More suitable for mass production; can be less expensive for large quantities [31] | Can be limited by precursor availability; complex processes may increase cost [31] |

| Structural Defects | Can introduce internal stress and surface defects [30] | Produces structures with fewer defects; more uniform [30] |

| Size & Shape Control | Limited control over monodispersity and complex shapes [30] | Excellent control over size, shape, and composition [30] [31] |

| Sample Crystallinity | Can result in amorphous or polycrystalline structures [30] | Often produces highly crystalline nanostructures [30] |

| Advantages | Simpler for large-scale production; uses existing bulk materials [31] | High precision; complex architectures; better surface chemistry control [30] [31] |

| Disadvantages | Surface imperfections; material waste; limited to simple geometries [30] | Can be time-consuming; expensive precursors; potential stability issues [30] |

The experimental data underlying this comparison is derived from standardized laboratory protocols. For instance, in mechanical milling (top-down), the particle size distribution is typically measured using laser diffraction or dynamic light scattering post-synthesis, revealing a broader dispersion compared to the narrower distribution achieved in bottom-up methods like chemical precipitation, where reaction kinetics and precursor concentration can be tightly controlled [30] [34]. The presence of defects in top-down synthesized nanomaterials is often confirmed through techniques like high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, which can detect crystallographic imperfections and strain [30].

Applications in Medical Device and Drug Development

The distinct properties of nanomaterials synthesized via these two routes dictate their suitability for specific biomedical applications.

Top-Down Applications