Nanostructured Surfaces for Bacterial Reduction: Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of nanostructured surfaces as a strategic solution for reducing bacterial load, a critical challenge in healthcare and biomaterial science.

Nanostructured Surfaces for Bacterial Reduction: Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of nanostructured surfaces as a strategic solution for reducing bacterial load, a critical challenge in healthcare and biomaterial science. It explores the foundational mechano-bactericidal mechanisms by which nanoscale topographies physically inactivate pathogens, offering an alternative to conventional antibiotics. The review details the latest methodological advances in fabricating these surfaces, from self-assembled biomimetic structures to anodized nanotubes, and their applications in medical implants, wound dressings, and biosensors. It further addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, including the complex role of protein fouling and the need for precise nanostructure design. Finally, the article critically assesses validation techniques and comparative performance data, synthesizing findings to outline a path for the clinical implementation of these advanced antibacterial interfaces.

The Mechano-Bactericidal Principle: How Nanotopographies Inactivate Bacteria

The Natural Blueprint: Insect Wing Nanostructures

Bioinspired nanostructures draw their design from natural surfaces that have evolved over millennia to combat microbial contamination. The wings of cicadas and dragonflies have garnered significant scientific interest because they possess nanoscale topographic features that impart potent antibacterial properties without the use of chemicals [1]. This mechanobactericidal effect offers a promising, antibiotic-free strategy to reduce bacterial colonization on surfaces, particularly in medical implant applications [2] [3].

These insect wings are not simply flat membranes; they are covered in a dense array of nanopillars or nanoprotrusions. When bacteria attempt to adhere to these surfaces, the physical interaction between the bacterial cell envelope and the sharp nanofeatures leads to cell death. The primary advantage of this mechanism is its physical nature, which reduces the likelihood of bacteria developing resistance compared to conventional chemical antibiotics [4].

Comparative Analysis of Natural Nanostructures

The following table summarizes the key dimensional characteristics of nanostructures found on various cicada and dragonfly wings, which are crucial for their antibacterial function.

Table 1: Nanostructure Dimensions on Insect Wings

| Insect Species | Wing Type | Nanofeature Type | Height (nm) | Diameter/Width (nm) | Spacing (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphipsalta cingulata [5] | Cicada | Nanopillar | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| Kikihia scutellaris [5] | Cicada | Nanopillar | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| Neotibicen Canicularis [6] | Cicada | Nanopillar Cone | ~200 | ~90 (pillar), ~150 (base) | ~180 (center-to-center) |

| M. intermedia [3] | Cicada | Conical Nanopillar | 241 | 156 | 165 |

| Sympetrum vulgatum [7] | Dragonfly | Irregular Nanostructure | 83 - 195 | 83 - 195 | Information Missing |

Antibacterial Performance of Natural Wings

The nanostructures on insect wings exhibit varying efficacy against different types of bacteria. The following table outlines the bactericidal performance observed in experimental studies.

Table 2: Antibacterial Efficacy of Natural Insect Wings

| Insect Species | Tested Bacteria | Gram Reaction | Reported Efficacy | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psaltoda claripennis (Cicada) [8] | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Negative | High | Mechanical rupture of bacterial cells observed. |

| Psaltoda claripennis (Cicada) [8] | Bacillus subtilis | Positive | Resistant | Rigid cell wall likely confers resistance. |

| Psaltoda claripennis (Cicada) [8] | Staphylococcus aureus | Positive | Resistant | Rigid cell wall likely confers resistance. |

| Diplacodes bipunctata (Dragonfly) [4] | P. aeruginosa, E. coli | Negative | High | Envelope deformation and penetration. |

| Diplacodes bipunctata (Dragonfly) [4] | S. aureus, B. subtilis | Positive | Effective | Capillary architecture enhances killing of Gram-positive types. |

Fabrication of Bioinspired Synthetic Nanostructures

To harness these antibacterial properties for biomedical applications, researchers have developed advanced techniques to mimic insect wing nanostructures on synthetic materials, especially those used for medical implants like titanium alloys [3] [6].

Common Fabrication Techniques

- Hydrothermal Etching: This method involves treating titanium alloy discs with alkaline solutions (e.g., KOH or NaOH) at high temperatures (150–180°C) in an autoclave. This process creates nano-structured surfaces by chemical etching, with the specific etchant influencing the resulting nanomechanical properties [9].

- Glancing Angle Deposition (GLAD): A physical vapor deposition technique used to create complex 3D nanofeatures. In one approach, a layer of self-assembled nanospheres (e.g., 200nm polystyrene) acts as a template. Subsequent oxygen plasma etching reduces the sphere size to create defined seeds, and then electron beam evaporation at a high incident angle (e.g., 85°) grows nanopillars on these seeds, closely replicating the cicada wing morphology [6].

- Thermal Oxidation: This process generates nanopillars on titanium alloy surfaces by oxidizing the material at high temperatures (e.g., 850°C for 5 minutes), resulting in a nanotopography primarily composed of rutile titanium dioxide (TiO₂) that mimics dragonfly wings [4].

Comparison of Fabricated Nanostructure Performance

The antibacterial success of synthetic mimics depends heavily on their geometric parameters. The table below compares the performance of surfaces fabricated using different methods.

Table 3: Performance of Bioinspired Synthetic Nanostructures

| Fabrication Method | Material | Key Nanofeature Dimensions | Target Bacteria | Reported Antibacterial Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Oxidation [4] | TiO₂ (Titanium Alloy) | Mimics dragonfly wing | S. aureus, E. coli, K. pneumoniae | Cell envelope deformation & penetration; induced oxidative stress; inhibited cell division. |

| GLAD [6] | Synthesized Nanostructures | Pillars: ~90 nm diameter, ~200 nm height; Base spacing: ~180 nm | E. coli | Bacteria puncturing and death observed. |

| Hydrothermal Etching (KOH) [9] | Titanium Alloy (Ti6Al4V) | Information Missing | Model for cell interaction | Reduced surface stiffness (20 ± 3 N/m) and altered short/long-range interaction forces. |

| Hydrothermal Etching (NaOH) [9] | Titanium Alloy (Ti6Al4V) | Information Missing | Model for cell interaction | Reduced surface stiffness (29 ± 4 N/m) and altered surface energy compared to control. |

Decoding the Bactericidal Mechanism

The initial understanding was that nanopillars kill bacteria solely by mechanically rupturing the cell membrane as it stretches between the pillars [2] [8]. However, more recent research reveals a more complex and multi-faceted mechanism.

The Mechanobactericidal Effect

The process begins with the adhesion of a bacterial cell to the nanopillar tips. Attractive forces, such as van der Waals forces, then cause the cell membrane to be pulled down the sides of the pillars [2] [5]. This adhesion creates a mechanical stress on the cell envelope. If this stress exceeds the elastic limit of the membrane, it can lead to irreversible rupture and cell death [8].

Beyond Mechanical Rupture: Oxidative Stress and Penetration

Advanced studies indicate that physical rupture is not the only pathway. Research on titanium nanopillars has shown that they can indent and penetrate the bacterial envelope without causing immediate lysis [4]. This physical insult triggers a physiological response in the bacteria, including the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). An overabundance of ROS leads to oxidative stress, which damages cellular components like proteins, lipids, and DNA, ultimately resulting in cell death [4]. Furthermore, nanopillars have been observed to inhibit bacterial cell division, adding another layer to their antibacterial efficacy [4].

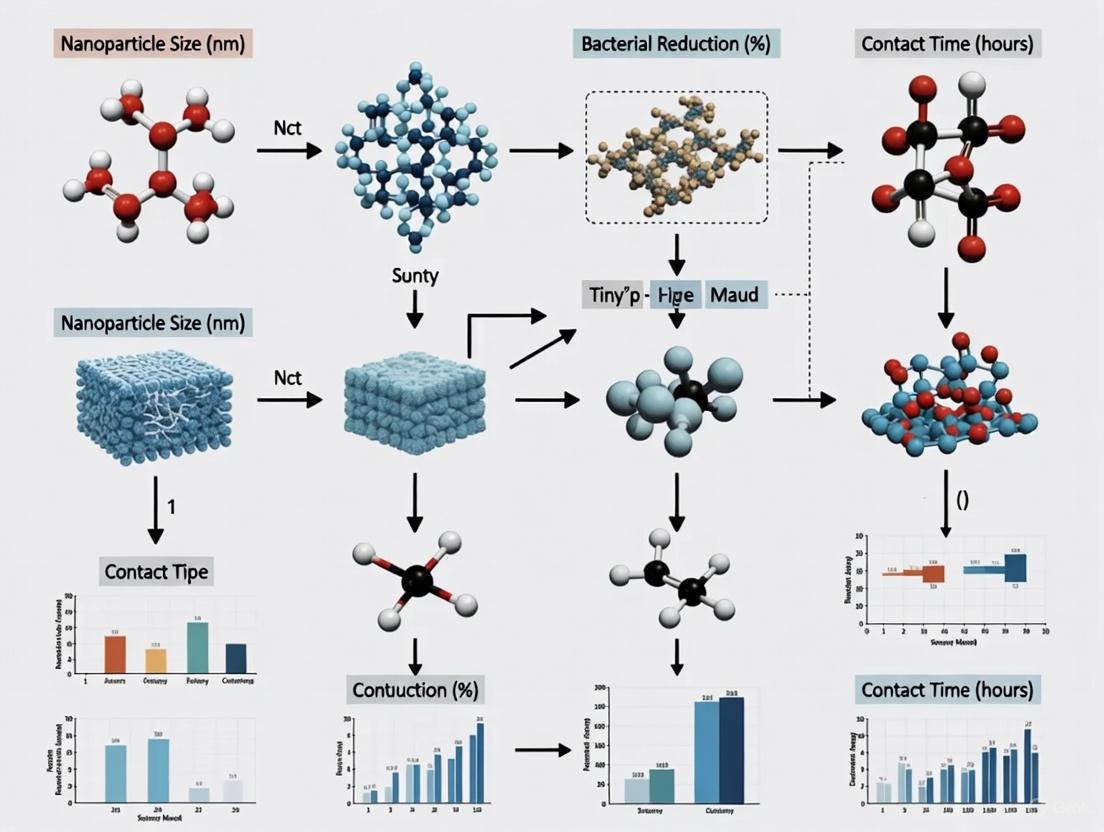

The following diagram illustrates the multi-mechanism pathway leading to bacterial death on nanopillar surfaces.

Essential Experimental Protocols for Evaluation

Robust evaluation of antibacterial nanostructures requires standardized protocols, though methods can vary across studies. The following outlines a common approach for assessing viability of bacteria on test surfaces.

Bacterial Viability Assay with Live/Dead Staining

This protocol is widely used to quantitatively distinguish between live and dead bacteria on a surface after contact [5].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Bacterial Suspension: Bacteria (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus) are cultured in a nutrient broth (e.g., Lysogeny broth) and grown to the mid-exponential phase, typically until an optical density at 600 nm (OD⁶⁰⁰) of 0.7 is reached [5].

- Fluorescent Stains:

- SYTO 9/Hoechst 33343: These cell-permeant nucleic acid stains label all bacteria, both live and dead, emitting green/blue fluorescence [8] [5].

- Propidium Iodide (PI): This cell-impermeant stain only enters bacteria with compromised membranes, binding to DNA and producing red fluorescence. It is used to indicate dead cells [8] [5].

Workflow:

- Sample Incubation: The nanostructured sample (e.g., a 5 mm disc) is incubated in the bacterial suspension for a set period (e.g., 1 hour at room temperature) [5].

- Staining: After incubation, the sample is exposed to a mixture of the fluorescent stains.

- Visualization and Analysis: The stained sample is visualized using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) or fluorescence microscopy. Live cells fluoresce green/blue, while dead cells with damaged membranes fluoresce red. The ratio of red to green/blue fluorescence provides a quantitative measure of bactericidal efficiency [8] [5].

Characterization of Nanostructure Morphology

Accurate characterization of the nanostructures themselves is critical for correlating structure with function.

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Provides high-resolution images of the surface topography and the morphological state of bacteria attached to the surface. Samples are often sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold/palladium to enhance conductivity before imaging [5] [6].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Used for detailed topographical analysis of the nanostructures, providing 3D profiles and quantitative data on height, spacing, and roughness. AFM can also be used in force spectroscopy mode to measure nanomechanical properties and interaction forces between a probe tip and the surface [7] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This table lists essential materials and reagents used in the fabrication and testing of bioinspired antibacterial nanostructures, as derived from the experimental protocols in the search results.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Category | Item | Function in Research | Example Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Materials | Medical Grade Titanium Alloy (Ti6Al4V) | A common biomaterial for orthopaedic implants used as a substrate for creating antibacterial nanostructures. | [4] [9] |

| Fabrication Reagents | Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) / Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Alkaline etchants used in hydrothermal etching to create nano-structured surfaces on titanium. | [9] |

| Polystyrene Nanospheres | Used as self-assembled templates or "seeds" for the controlled growth of nanopillars in GLAD fabrication. | [6] | |

| Bacterial Culture | Lysogeny Broth (LB Medium) | A nutrient-rich growth medium used for cultivating bacterial strains for testing. | [5] |

| Glycerol in PBS | Used as a cryoprotectant for preparing long-term storage stocks of bacterial cultures. | [5] | |

| Viability Assay | LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit (SYTO 9 & PI) | A fluorescent stain kit used to simultaneously label live (green) and dead (red) bacteria for viability counts. | [8] |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | A red-fluorescent nucleic acid stain that only penetrates cells with damaged membranes, labeling dead cells. | [5] | |

| Hoechst 33342 | A blue-fluorescent cell-permeant DNA stain that labels all bacterial cells. | [5] | |

| Characterization | Gold/Palladium Target | Used for sputter-coating non-conductive samples (e.g., insect wings) to make them conductive for SEM imaging. | [5] |

The development of nanostructured surfaces as a means to combat bacterial colonization represents a paradigm shift in antibacterial strategies, moving beyond conventional biochemical approaches to exploit fundamental physical laws. These surfaces induce bacterial cell death through mechanical forces, primarily by piercing the cell envelope, stretching the membrane to the point of critical failure, or initiating explosive lysis from within. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these physical mechanisms, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to assist researchers in evaluating and selecting appropriate nanostructured surfaces for specific applications. The physical disruption of bacterial membranes offers a compelling advantage over traditional antibiotics: it minimizes the likelihood of resistance development by targeting the structural integrity of the cell itself, a feature that is difficult for bacteria to evolve countermeasures against. Understanding the nuances of piercing, stretching, and lysis is therefore critical for advancing the field of mechano-bactericidal materials and their application in healthcare, industrial, and environmental settings.

Comparative Analysis of Disruption Mechanisms

The following sections dissect the three primary physical mechanisms, summarizing their key characteristics, effectiveness, and experimental evidence.

Piercing: Nanostructure-Induced Membrane Penetration

The piercing mechanism involves the physical penetration of the bacterial cell envelope by sharp, high-aspect-ratio nanostructures. This is a direct physical attack that compromises the integrity of the cell wall and underlying membranes.

- Mechanism of Action: When a bacterial cell adheres to a surface featuring nano-protrusions like nanospikes or nanorods, its own weight and adhesive forces can drive these sharp features through the outer membrane (in Gram-negative bacteria) and the cell wall, ultimately rupturing the inner membrane. This penetration creates physical holes, leading to uncontrolled efflux of cellular contents and influx of external media, resulting in rapid cell death.

- Key Evidence: Recent advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques have directly detected membrane penetration. Using a mechanosensitive fluorescent probe (Flipper-TR), researchers have visualized and quantified the localized stress and compression of bacterial membranes upon contact with nanostructured, mechano-bactericidal substrates, confirming the piercing action [10].

- Material Design: The efficacy of piercing is highly dependent on nanostructure geometry. Surfaces with sharper tips, higher aspect ratios, and optimal inter-structure spacing (typically comparable to or smaller than the size of a bacterial cell) are most effective. Materials such as black silicon and nanostructured titanium are prominent examples that utilize this mechanism [11].

Stretching: Turgor Pressure-Driven Membrane Expansion

Stretching, or membrane bulging, is a mechanism where defects in the cell wall lead to the uncontrolled expansion of the underlying membrane due to the cell's internal turgor pressure. This is often an indirect consequence of antibiotic action or enzymatic activity.

- Mechanism of Action: Many antibiotics, such as β-lactams (e.g., cephalexin), inhibit enzymes responsible for cell wall synthesis and cross-linking. This results in large defects in the peptidoglycan layer. The rigid cell wall, which normally restrains the inner membrane, is compromised. The high internal turgor pressure (approximately 0.3–2 atm in E. coli) then forces the membrane to bulge outward through these defects, forming a spherical bleb [12].

- Key Evidence and Dynamics: Research on Escherichia coli has delineated this process into two distinct phases. The initial formation of a "bulge" occurs rapidly, on a timescale of about 1 second, as the membrane relaxes through the wall defect. This is followed by a slower "swelling" phase, lasting about 100 seconds, where the bulge grows as wall defects enlarge. Final lysis occurs when the membrane exceeds its yield areal strain [12].

- Energetics: The process is energetically favorable because the relaxation of the stretching and entropic energies of the inner membrane outweighs the bending energy cost of forming the bulge. Lysis is the ultimate endpoint when the stretched membrane can no longer withstand the pressure [12].

Explosive Lysis: Endolysin-Mediated Catastrophic Rupture

Explosive cell lysis is a biologically programmed event that results in the instantaneous and catastrophic disintegration of the bacterial cell, serving as a source of extracellular DNA and membrane vesicles for the biofilm community.

- Mechanism of Action: In bacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a sub-population of cells can undergo a rapid lytic event mediated by a cryptic prophage endolysin (e.g., Lys protein). This endolysin degrades the peptidoglycan cell wall. The loss of this primary stress-bearing structure causes the cell to rapidly transition from a rod to a round shape in less than 5-10 seconds, after which it explodes [13].

- Key Evidence: Live-cell super-resolution microscopy has captured these events, showing the annihilation of the cell and the simultaneous release of cytoplasmic content and shattered membrane fragments that spontaneously form membrane vesicles (MVs). This lysis is essential for providing extracellular DNA that strengthens the biofilm matrix [13].

- Induction: Explosive lysis can be a stochastic event or induced by external stresses such as antibiotic treatment (e.g., ciprofloxacin) or genotoxic stress (e.g., mitomycin C), and is dependent on the RecA-mediated SOS stress response [13].

Quantitative Comparison of Mechanisms

The table below synthesizes key quantitative data and characteristics for the three primary disruption mechanisms.

Table 1: Comparative Data on Bacterial Membrane Disruption Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Primary Trigger | Key Physical Force | Characteristic Timescale | Key Observational Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piercing | Contact with sharp nanostructures | Localized mechanical stress & penetration | Instantaneous upon contact | Fluorescence lifetime changes indicating membrane compression [10] |

| Stretching | Cell wall defect (e.g., from β-lactams) | Internal turgor pressure (~0.5 atm) | Bulge: ~1 s; Swelling: ~100 s [12] | Phase-contrast microscopy of bulge formation and growth [12] |

| Explosive Lysis | Activation of prophage endolysin | Peptidoglycan degradation & turgor pressure | Rod-to-round transition: <5-10 s [13] | Super-resolution microscopy of cell explosion and vesicle formation [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

To facilitate replication and further research, this section outlines the detailed methodologies from foundational studies on stretching and explosive lysis.

Protocol: Analyzing Membrane Bulging and Lysis via β-lactam Treatment

This protocol is adapted from studies on the mechanics of antibiotic-induced lysis in E. coli [12].

- 1. Bacterial Strain and Growth: Use wild-type E. coli (e.g., MG1655). Grow cells in a standard rich medium (e.g., LB) to mid-exponential phase.

- 2. Cell Wall Digestion: Treat the bacterial culture with a β-lactam antibiotic such as cephalexin at a concentration of 50 μg/mL. This inhibits transpeptidase enzymes, preventing new cross-links in the peptidoglycan layer and leading to large wall defects as the cell grows.

- 3. Microscopy and Image Analysis:

- Mount the treated cells on an agarose pad for live-cell imaging.

- Use phase-contrast or differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy to observe morphological changes at a frame rate sufficient to capture rapid dynamics (high-speed imaging).

- Quantify the timescales of bulging (initial protrusion formation) and swelling (protrusion growth) by analyzing video data.

- 4. Physical Modeling:

- Model the cell wall as a rigid, orthotropic cylindrical shell with elastic moduli (e.g., axial direction, Yxw=0.1 N/m; circumferential direction, Yyw=0.2 N/m).

- Model the inner and outer membranes as linear-elastic shells with area stretch moduli of ~0.1 N/m.

- Calculate the free energy of the system, accounting for cell wall and membrane stretching energies, bending energies, and the entropy of mixing related to turgor pressure, to predict bulge formation and stability.

Protocol: Visualizing Explosive Cell Lysis in Biofilms

This protocol is based on research investigating explosive lysis in P. aeruginosa biofilms [13].

- 1. Bacterial Strain and Biofilm Culture: Use P. aeruginosa PAK or PAO1. Cultivate interstitial biofilms on a glass-bottom dish using a minimal medium to promote monolayer biofilm formation that is conducive to microscopy.

- 2. Fluorescent Staining:

- eDNA Staining: Add a cell-impermeant fluorescent nucleic acid stain like TOTO-1 or SYTOX Green to the medium to label extracellular DNA (eDNA) released upon lysis.

- Cytoplasmic Labeling (Optional): Engineer bacteria to express a cytoplasmic fluorescent protein (e.g., CFP) to visualize the release of cytoplasmic content.

- Viability Staining (Optional): Use a live-cell impermeant stain like ethidium homodimer-2 (EthHD-2) to confirm membrane integrity of round cells prior to explosion.

- 3. Stress Induction (Optional): To induce higher rates of lysis, expose the biofilm to a gradient of ciprofloxacin (antibiotic stress) or mitomycin C (genotoxic stress).

- 4. Time-Lapse Super-Resolution Microscopy:

- Image the biofilm using both phase-contrast and fluorescence channels over time.

- Use high-resolution microscopy (e.g., STORM/PALM) to capture the formation of membrane vesicles from shattered membrane fragments post-lysis.

- Analyze the survival time of round cells and the frequency of eDNA release events.

- 5. Genetic Validation: Construct a mutant deficient in the endolysin gene (Δlys) to confirm the protein's role. Explosive lysis should be abrogated in the mutant and restored with wild-type lys provided in trans.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, defined using the DOT language, illustrate the logical progression of the explosive lysis mechanism and a general workflow for evaluating nanostructured surfaces.

Explosive Lysis Pathway

Nanostructured Surface Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This section details key reagents, materials, and tools used in the experimental studies cited in this guide, providing a resource for researchers designing their own experiments.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Studying Bacterial Membrane Disruption

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Flipper-TR | A mechanosensitive fluorescent probe that embeds in membranes; its fluorescence lifetime inversely correlates with membrane tension. | Visualizing and quantifying membrane stress upon contact with nanostructured surfaces [10]. |

| Cephalexin | A β-lactam antibiotic that inhibits transpeptidases, preventing cell wall cross-linking and creating defects that lead to bulging. | Inducing membrane stretching and lysis in E. coli for mechanistic studies [12]. |

| Streptolysin O (SLO) | A pore-forming toxin that creates large (~30 nm) pores in mammalian and bacterial membranes for controlled permeabilization. | Used in cell resealing techniques to deliver membrane-impermeable molecules into cells [14]. |

| Titanium with Micro/Nanostructure | A biocompatible material whose surface is modified with nanostructures (e.g., nanotubes) to impart antibacterial properties. | Studying competitive growth of osteoblasts vs. bacteria and piercing mechanisms [11]. |

| TOTO-1 / SYTOX Green | Cell-impermeant nucleic acid stains that fluoresce upon binding to DNA. Used to mark extracellular DNA (eDNA). | Visualizing sites of explosive cell lysis in bacterial biofilms [13]. |

| Quartz Crystal (QC) with Nanostructures | A macroscopic oscillator whose surface is modified with a "forest" of nanobristles to amplify interactions with the surrounding medium. | Studying exponential enhancement of viscous dissipation at the solid-gas interface [15]. |

| Endolysin (Lys) Mutant | A genetically engineered P. aeruginosa strain with a knockout of the prophage endolysin gene (PA0629). | Validating the essential role of endolysin in explosive cell lysis and biofilm matrix development [13]. |

The Critical Role of Surface Roughness, Nanospike Density, and Aspect Ratio

The growing challenge of antibiotic resistance has intensified the focus on developing non-chemical antibacterial surfaces for applications in healthcare, public hygiene, and medical implants. Inspired by natural nanostructures found on insect wings, engineered surfaces with specific topographic features have demonstrated remarkable ability to inhibit bacterial colonization and cause bacterial death through mechanical contact. This review objectively compares the performance of various nanostructuring approaches, focusing on three critical parameters: surface roughness, nanospike density, and aspect ratio. These parameters collectively determine the mechanobactericidal efficacy of nanostructured surfaces by influencing bacterial adhesion, membrane stress, and eventual rupture.

The mechanobactericidal effect occurs when nanoscale features on a surface apply sufficient stress to bacterial cell walls and outer membranes, compromising their structural integrity. While the exact killing mechanism continues to be investigated, several hypotheses have been proposed, including direct piercing of the cell membrane, creep failure, motion-induced shear failure, and oxidative stress-induced cell death. What remains clear is that surface topography plays a decisive role in this process, with specific geometric parameters directly influencing bactericidal efficiency. Understanding these parameters enables researchers to design surfaces that maximize antibacterial activity while maintaining biocompatibility and mechanical stability.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Nanostructured Surfaces

The following tables summarize key experimental findings from recent studies, comparing the antibacterial performance of surfaces with different roughness characteristics, nanospike geometries, and material compositions.

Table 1: Impact of Surface Roughness on Bacterial Adhesion

| Material Type | Surface Treatment | Roughness (Ra, μm) | Bacterial Strain | Adhesion/Bactericidal Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanohybrid Composite Resin (Charisma Topaz) | Mylar strip (control) | 0.07 ± 0.01 | S. mutans | 3.57 ± 0.32 log CFU/mL | [16] |

| Nanohybrid Composite Resin (Charisma Topaz) | Sof-Lex Polishing | 0.09 ± 0.03 | S. mutans | No significant difference from control | [16] |

| Nanofilled Composite Resin (Estelite Asteria) | Mylar strip (control) | 0.07 ± 0.01 | S. mutans | Significantly lower than nanohybrid | [16] |

| Nanofilled Composite Resin (Estelite Asteria) | Opti1Step Polishing | 0.09 ± 0.03 | S. mutans | No significant difference from control | [16] |

Table 2: Performance of Biomimetic Nanospike Surfaces

| Material/Substrate | Fabrication Method | Nanospike Feature | Bacterial Strain | Reduction/Efficacy | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) Film | APLTP + Annealing | Sharp-edged nanospikes | E. coli | >99.9% (CFU < 10) | Combined sharpness and controlled wettability | [17] |

| Titanium Dental Implant | H₂SO₄/H₂O₂ Treatment | Uniform nanospike layer | Multiple oral strains | 70-90% reduction | Improved osseointegration (56% vs 41% bone contact) | [18] |

| Titanium Dental Implant | Grit-blasting + Acid Etching (Control) | Conventional roughness | Multiple oral strains | Control baseline | Lower bone contact index (41%) | [18] |

| Black Silicon | Reactive Ion Etching | Nanopillars | Various | Bactericidal | Replicates cicada wing effect | [17] |

Table 3: Bacterial Cell Geometry and Deformation Parameters

| Parameter | Bacterial Type | Typical Value | Experimental Context | Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect Ratio (η) | Rod-shaped (e.g., E. coli) | 4.14 ± 0.17 | Steady-state growth | Preserved across growth conditions, influences contact area with nanostructures | [19] |

| Aspect Ratio (η) | Coccoid (e.g., S. aureus) | 1.38 ± 0.18 | Under antibiotic exposure | Affects the mechanical stability and points of stress application | [19] |

| Surface-to-Volume Scaling | Rod-shaped Bacteria | S ≈ 2πV²/³ | Nutrient adaptation | Links cell size to membrane tension under deformation | [19] |

| Cell Wall Elasticity | E. coli | ~300% increase from relaxed state | Isolated sacculi measurement | Indicates capacity to withstand stretching before rupture | [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Assessing Surface Roughness and Bacterial Adhesion on Composites

This methodology is designed to evaluate how different polishing procedures affect the surface roughness of composite resins and subsequent adhesion of Streptococcus mutans [16].

Specimen Preparation:

- Materials: Two composite resins are used: a nanofilled (Tokuyama Estelite Asteria) and a nanohybrid (Charisma Topaz). The key research reagents are listed in Table 4.

- Fabrication: Eighty disk-shaped specimens (8 mm diameter, 2 mm thickness) are fabricated using a cylindrical mold. A transparent Mylar strip is placed over the material and pressed with a glass slide to extrude excess material and create a flat surface before light-curing.

- Polymerization: Specimens are polymerized using an LED light-curing device (Elipar Free Light, 1200 mW/cm²) according to manufacturers' instructions (20s for Charisma Topaz, 10s for Estelite Asteria).

- Polishing: The specimens are divided into four groups (n=10 per group per material):

- Group A (Control): No polishing, Mylar strip surface only.

- Group B (Multi-step): Polished with Sof-Lex discs (coarse, medium, fine, superfine) at 10,000-30,000 rpm for 20s per disc.

- Group C (Two-step): Polished with Clearfil Twist Dia diamond-impregnated wheels at 10,000 rpm for 20s per wheel.

- Group D (One-step): Polished with Opti1Step diamond-impregnated polisher at 10,000 rpm for 20s under dry conditions.

Surface Roughness and Microbiological Analysis:

- Roughness Measurement: Surface roughness (Ra) is measured using a profilometer (Mahr M1 Perthometer). Three measurements are taken at different points on each sample, and the mean Ra value is calculated.

- Sterilization: All composite samples are sterilized in an autoclave at 121°C and 1 atm pressure for 15 minutes.

- Saliva Treatment: Sterilized samples are divided into two subgroups. The "artificial saliva-treated" group is incubated with artificial saliva (containing mucin) for 1 hour at room temperature to form a salivary pellicle. The "non-treated" group is not exposed to saliva.

- Bacterial Adhesion Assay: A solution containing S. mutans (ATCC 25175) is added to all samples, which are then incubated at 35–37°C for 24 hours. Adhered bacteria are quantified by colony counts, presented as log CFU/mL [16].

Experimental Workflow for Composite Roughness and Adhesion Study

Protocol 2: Fabrication of Biomimetic Nanospikes via Plasma Treatment

This protocol details a scalable method for creating sharp-edged nanospikes on polymer films using Atmospheric-Pressure Low-Temperature Plasma (APLTP), inspired by the bactericidal nanostructures on cicada wings [17].

PMMA Film Preparation and Plasma Treatment:

- Materials: Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) and ethyl lactate solvent.

- Film Casting: A 30 wt% PMMA solution in ethyl lactate is prepared. The solution is spin-coated onto a glass substrate at 1800 rpm for 24 seconds. The coated substrate is pre-baked in an oven at 100°C for 60 seconds, resulting in an initial film thickness of approximately 5 µm.

- Plasma Treatment: The PMMA-coated substrate is irradiated with APLTP. The plasma is generated with a He/O₂ gas mixture (2.0 slm He, 60 sccm O₂) at an RF power of 120 W (27.12 MHz). The plasma irradiation time is 5 seconds per cycle, followed by a 15-second cooling period. This cycle is repeated multiple times to achieve the desired etching and nanostructuring.

- Annealing: To control surface wettability while maintaining structural sharpness, the plasma-treated substrate is placed in an oven at 120°C for 5 days. This annealing step closes microscopic pores and restores hydrophobicity, which is crucial for optimal antibacterial performance.

Surface Characterization and Antibacterial Testing:

- Topography Analysis: The surface profile and formation of micro/nanostructures are confirmed using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). The evaluation area is 5 x 5 µm² with a resolution of 512 x 512 points.

- Wettability Assessment: The contact angle is measured using a sessile drop method with 2 µL of pure water to evaluate surface hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity.

- Antibacterial Assay: Antibacterial performance is evaluated against Escherichia coli according to ISO 22196 standards. The reduction in bacterial colonies is quantified, with counts below 10 CFU considered the detection limit [17].

Protocol 3: Creating Bactericidal Nanospikes on Titanium Implants

This method describes a chemical passivation process to generate a nanotextured, spiked layer on titanium dental implants to confer bactericidal properties without compromising osseointegration [18].

Surface Nanotexturing and Characterization:

- Material Preparation: Commercially pure titanium grade 3 implants with a grit-blasted rough surface serve as the substrate.

- Chemical Passivation: Test implants are immersed in a solution of sulfuric acid and hydrogen peroxide for 2 hours to form the nanospike surface. Standard implants without this treatment are used as controls.

- Surface Characterization:

- Roughness: Measured using white light interferometry (Wyko NT1100). The amplitude parameter (Sa) is determined from an analysis area of 124.4 x 94.6 µm.

- Wettability and Surface Energy: Contact angle analysis is performed with distilled water and formamide. The surface energy is calculated using the Owens, Wendt, Rabel, and Kaelble (OWRK) equation.

- Hydrogen Content: Analyzed using an Inert Gas Fusion LECO TCH600 to ensure no hydrogen embrittlement occurs.

- Fatigue Behavior: Evaluated using a servo-hydraulic testing machine (MTS Bionix) according to ISO 14801:2007 standards, with implants tested at a 30-degree angle under cyclical loading.

Biological and Bactericidal Testing:

- Osseointegration Assay: Human osteoblastic cells (SaOs-2) are cultured on the surfaces. Cell adhesion is measured at 3 and 7 days, and mineralization is analyzed via alkaline phosphatase levels at 14 days.

- In Vivo Bone Contact: Implants are inserted into rabbit tibiae. After 21 days, the bone-implant contact index is determined histologically.

- Bactericidal Capacity: Bacterial colonization assays are conducted using four relevant bacterial strains. The percentage reduction in colonization on the nanospike surface compared to the control is calculated [18].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Their Functions

| Category/Item | Function in Research | Specific Example/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Composite Resins | Substrate for testing roughness vs. adhesion | Nanofilled (Estelite Asteria) vs. Nanohybrid (Charisma Topaz) [16] |

| Polishing Systems | Creating defined surface finishes on composites | Sof-Lex (multi-step), Clearfil Twist Dia (two-step), Opti1Step (one-step) [16] |

| Atmospheric-Pressure Low-Temperature Plasma (APLTP) | Scalable fabrication of nanostructures on polymers | Creating sharp-edged nanospikes on PMMA films [17] |

| Chemical Passivation Agents | Nanotexturing of metal surfaces | Sulfuric Acid & Hydrogen Peroxide for creating nanospikes on titanium [18] |

| Profilometer/Interferometer | Quantifying surface roughness (Ra) | Mahr M1 Perthometer; Wyko NT1100 Optical Interferometer [16] [18] |

| Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | High-resolution imaging of nanotopography | Veeco Dimension Icon for characterizing nanospikes on PMMA [17] |

| Contact Angle Goniometer | Measuring surface wettability | OCA15plus-Dataphysics for surface energy calculations [18] |

| Standard Bacterial Strains | Evaluating bactericidal/adhesion performance | S. mutans (ATCC 25175), E. coli, oral pathogens [16] [17] [18] |

Mechanisms of Action and Interparameter Relationships

The antibacterial action of nanostructured surfaces is a complex process initiated by mechanical contact. The following diagram synthesizes the current understanding of the bactericidal pathway, from initial adhesion to cell death, and highlights how key surface parameters influence each step.

Proposed Mechanobactericidal Pathway and Parameter Influence

The relationship between these parameters and bacterial cell geometry is critical. Rod-shaped bacteria like E. coli maintain a conserved aspect ratio of approximately 4.14 during steady-state growth, following a surface-to-volume scaling relation (S ≈ 2πV²/³) [19]. This constant aspect ratio implies tighter geometric constraints than previously thought and influences how the cell membrane interacts with surface nanostructures. The mechanical failure likely occurs when the energy imposed by the nanostructures exceeds the elastic capacity of the bacterial cell wall, which can stretch up to 300% from its relaxed state [2]. Parameters like nanospike density directly influence the number of stress application points, while spike sharpness and aspect ratio concentrate stress to overcome the membrane's mechanical strength, leading to rupture.

Distinguishing Bactericidal vs. Anti-Adhesion Strategies

In the face of rising antibiotic resistance, the development of novel non-antibiotic strategies to combat bacterial infections has become a critical focus in biomedical research. Among the most promising approaches are those that target the initial interaction between bacteria and material surfaces, primarily categorized as bactericidal and anti-adhesion strategies. Bactericidal strategies aim to physically destroy bacterial cells upon contact with a surface, while anti-adhesion strategies focus on preventing bacterial attachment in the first place. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two mechanisms, focusing on their application to nanostructured surfaces, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their evaluation and selection process.

Core Mechanisms and Design Principles

The fundamental difference between these strategies lies in their approach to managing bacterial contamination. Bactericidal surfaces are designed to kill bacteria, whereas anti-adhesion surfaces are designed to repel them [20].

- Bactericidal (Contact-Killing) Mechanisms: These are often considered "active" strategies. Surfaces are engineered with specific nanoscale topographic features, such as nanopillars or nanowires, that mechanically rupture bacterial cell membranes upon contact. The killing mechanism is primarily physical, driven by the interaction between the nanostructures and the bacterial cell wall, leading to cell lysis and death [21] [22] [23].

- Anti-Adhesion Mechanisms: These are typically classified as "passive" strategies. They work by modifying the surface's physicochemical properties—such as topography, chemistry, wettability, and charge—to create an energy barrier that minimizes bacterial attachment. This is often achieved by creating a highly hydrophilic surface that forms a hydration layer, acting as a physical and energetic shield against approaching bacteria [20] [24].

The table below summarizes the key distinguishing characteristics of each strategy.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Bactericidal and Anti-Adhesion Strategies

| Feature | Bactericidal Strategy | Anti-Adhesion Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Kill bacteria upon contact | Prevent initial bacterial attachment |

| Mechanism of Action | Physical rupture of the cell membrane by nanostructures | Modulation of surface energy, charge, and topography |

| Typical Surface Chemistry | Often cationic polymers (e.g., quaternary ammonium) | Hydrophilic/zwitterionic polymers (e.g., PEG) |

| Effect on Biofilm | Disrupts biofilm by killing founder cells | Inhibits biofilm formation by preventing initial colonization |

| Potential for Resistance | Considered low, as mechanism is physical [23] | Considered low, as it does not target viability |

| Key Challenge | Potential cytotoxicity to host cells [20] | May not kill bacteria, which could relocate and colonize other surfaces |

Comparative Experimental Data and Performance

Experimental data reveals how these strategies perform under various conditions, highlighting their respective strengths and limitations.

Bactericidal Efficacy of Nanostructured Surfaces

Nanostructured titanium surfaces have demonstrated significant bactericidal efficacy under both static and dynamic flow conditions, which are more representative of real-world applications like implants and catheters.

Table 2: Experimental Bactericidal Efficacy of a Nanostructured Titanium Surface [25]

| Bacterial Species | Static Condition (0 Pa) | Fluid Flow Condition (10 Pa) | Efficacy Increase under Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram-negative) | ~40% | ~60% | ∼1.5-fold |

| Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) | ~20% | ~60% | ∼3-fold |

This data shows that fluid flow can significantly enhance the bactericidal effect, particularly for S. aureus. The study concluded that the efficacy was independent of the fluid wall shear stress level once flow was introduced [25].

Anti-Adhesion Performance via Microstructure Engineering

Research on copper samples has shown that microstructural refinement through High-Pressure Torsion (HPT) can enhance anti-adhesion properties without altering surface chemistry.

Table 3: Anti-Adhesion Effect of HPT-Processed Copper on S. aureus [26]

| Sample Type | Grain Size (nm) | Dislocation Density (m⁻²) | Bacterial Adhesion (Relative to Annealed Cu) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annealed (Reference) | 27,700 | 9.18 × 10¹¹ | Baseline (100%) |

| HPT13.75 | ~300 | 5.15 × 10¹⁴ | Reduced |

| HPT53.75 | ~140 | 3.37 × 10¹⁴ | Further Reduced |

The study found a linear correlation between increased luminous intensity (indicating fewer adherent bacteria) and the inverse square root of grain size (grain size−0.5), directly linking material microstructure to anti-adhesion performance [26].

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core mechanisms and experimental workflows for both strategies.

Bactericidal Mechanism of Nanostructured Surfaces

Anti-Adhesion Therapeutic Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This section details essential materials and reagents used in studying bactericidal and anti-adhesion surfaces, providing a foundation for experimental design.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Category | Item | Function / Relevance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Surfaces | Titanium (Ti-6Al-4V) with nanowires | Model nanostructured surface for studying bactericidal efficacy under flow [25]. | Bactericidal |

| High-Pressure Torsion (HPT) processed Copper | Model for studying the isolated effect of microstructural defects (grain boundaries, dislocations) on anti-adhesion properties [26]. | Anti-Adhesion | |

| Bacterial Strains | Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) | Common model for Gram-positive infections; used to test efficacy against thick peptidoglycan layer [25] [26]. | Both |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram-negative) | Common model for Gram-negative, biofilm-forming bacteria; used to test efficacy against outer membrane [25]. | Both | |

| Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) | Standard model organism for initial screening of antibacterial properties [20]. | Both | |

| Inhibitors & Agents | MAM7-coated polystyrene microbeads | Competitive inhibitor that blocks bacterial adhesion to host cells by saturating binding sites [27]. | Anti-Adhesion |

| FimH antagonists (e.g., biphenyl mannosides) | High-affinity, orally available compounds that block adhesion of uropathogenic E. coli [28]. | Anti-Adhesion | |

| Pilicides and Curlicides | Small molecules that inhibit the assembly of chaperone-usher pili and curli fibers, critical for adhesion [28]. | Anti-Adhesion | |

| Analysis Tools | Microfluidic Devices (MFD) | Enables testing of bacterial adhesion and viability under controlled fluid wall shear stress [25]. | Both |

| Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) | Used for high-resolution analysis of the bacterium-substrate interface, revealing bacterial membrane damage [26]. | Bactericidal | |

| Fluorescence Staining (Live/Dead) | Standard protocol for enumerating viable and non-viable adherent bacteria on a surface [25]. | Both |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

- Surface Fabrication: Use a 1 mm thick Ti-6Al-4V sheet. Polish substrates to a surface roughness of 0.04 μm Ra. Fabricate nanowire structures on the polished surface via a hydrothermal synthesis process.

- Microfluidic Device (MFD) Setup: Design the MFD as a parallel-plate flow chamber. Sterilize the assembled device and substrates (70% v/v ethanol wash followed by UV exposure for 20 minutes).

- Bacterial Preparation: Cultivate P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Suspend bacteria in an appropriate fluid medium at a fixed concentration.

- Flow Experiment: Pump the bacterial suspension through the MFD at defined flow rates (e.g., 0.12, 4.00, 8.00, 12.00 mL/min) to generate a range of fluid wall shear stress (0 - 10 Pa). Include a no-flow static condition as a control.

- Post-Experiment Analysis: Retrieve substrates from the MFD. Stain the adhered bacteria with a fluorescent live/dead viability kit. Image the surfaces using fluorescence microscopy and enumerate live and dead cell counts.

- Sample Preparation: Process pure copper samples using High-Pressure Torsion (HPT) for 1 and 5 rotations. Use an annealed copper sample (e.g., 600°C for 2 hours) as a micro-grained reference.

- Surface Preparation (Critical Step): Prepare all sample surfaces using a method that ensures comparable and very low surface roughness (Average Roughness, Ra ~4-7 nm) to isolate the effects of microstructure.

- Material Characterization: Perform microhardness measurements across the sample diameter. Use techniques like X-ray diffraction to determine dislocation density and grain size.

- Bacterial Adhesion Test: Incubate the prepared surfaces with Staphylococcus aureus suspension for a defined period under controlled conditions.

- Analysis: After incubation, stain the adherent bacteria with a fluorescent dye. Use luminometric analysis to quantify the number of adhered bacteria relative to the reference sample. Perform focused ion beam (FIB) milling and STEM-EDX analysis on selected bacterium-substrate interfaces to study the intercellular bacterial response.

Both bactericidal and anti-adhesion strategies offer compelling, resistance-resistant alternatives to conventional antibiotics. The choice between them depends heavily on the specific application. Bactericidal nanostructured surfaces are highly effective in eliminating bacteria but require careful design to mitigate potential cytotoxicity and ensure durability. Anti-adhesion strategies, through chemical or microstructural means, offer a prophylactic approach by preventing colonization and are inherently less cytotoxic. Future directions point towards the development of hybrid systems that integrate both active and passive mechanisms to achieve synergistic effects, enhanced efficacy, and prolonged functionality under complex physiological conditions [20]. The ongoing challenge for researchers is to optimize these designs for large-scale production and successful clinical translation.

Engineering and Implementing Antibacterial Nanostructures in Biomedical Devices

The rising challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has intensified the focus on developing surfaces for medical implants that can inherently resist bacterial colonization. Within this research domain, the creation of nanostructured surfaces on titanium (Ti) alloys via electrochemical anodization has emerged as a leading strategy. This technique enables the fabrication of highly ordered titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanotube arrays, which are actively investigated for their dual capacity to enhance osseointegration and provide antibacterial functionality. This guide provides a comparative evaluation of different anodization protocols and substrate manufacturing methods, presenting objective experimental data on the performance of the resulting TiO2 nanotube structures. The content is framed within the broader thesis of evaluating nanostructured surfaces for bacterial reduction, providing researchers and scientists with a detailed analysis of protocols and outcomes.

Core Mechanism and Antibacterial Action of TiO2 Nanotubes

The antibacterial efficacy of TiO2 nanotubes is primarily driven by photocatalytic pathogen inactivation. Upon exposure to light, particularly ultraviolet (UV) light, TiO2 acts as a photocatalyst. The energy from the light excites electrons, creating electron-hole pairs. These charge carriers migrate to the surface and react with water and oxygen, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide radical anions (O2•−) and hydroxyl radicals (HO•) [29].

These ROS are highly oxidizing and inflict irreversible damage on bacterial cells. The mechanism, illustrated in the diagram below, involves a multi-stage attack: ROS first cause oxidative damage to the cell wall and membrane. This compromise of structural integrity allows ROS and, to a lesser extent, nanoparticles to penetrate the cytoplasm, leading to leakage of intracellular components, direct oxidative damage to proteins and nucleic acids, and ultimately, cell lysis and mineralization [29]. This multi-target mechanism makes it difficult for bacteria to develop resistance, a significant advantage over conventional antibiotics.

The susceptibility of bacteria to this photocatalytic attack is influenced by their cell wall structure. Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., E. coli), with their thinner peptidoglycan layer and outer membrane, are generally more susceptible than Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., S. aureus), which have a thicker peptidoglycan layer [29]. Furthermore, the nanotopography of the TiO2 layer itself can physically influence cell behavior. While it enhances protein adsorption and fibroblast adhesion for better soft tissue integration, the nanoscale features may also mechanically disrupt bacterial membranes [30].

Experimental Protocols for Fabrication and Characterization

Fabrication via Electrochemical Anodization

Electrochemical anodization is a relatively simple, cost-effective, and versatile technique suitable for implants with complex geometries [31]. The fundamental setup involves a two-electrode or three-electrode electrochemical cell where the titanium alloy substrate serves as the anode, and an inert material (e.g., graphite or platinum) acts as the cathode. Both are immersed in a fluoride-containing electrolyte.

- Key Process: When a constant voltage (DC) is applied, the titanium substrate oxidizes, forming a TiO2 layer. The fluoride ions (F⁻) in the electrolyte chemically dissolve this oxide, leading to the formation of a nanoporous layer. Under optimized conditions, the balance between electrochemical oxide growth and chemical dissolution leads to the self-organization of a highly ordered nanotubular array [31].

- Critical Parameters: The morphology of the nanotubes—including their diameter, length, and wall smoothness—is precisely tunable by varying anodization parameters such as applied voltage, duration, electrolyte composition, and temperature [31] [32].

A generalized workflow for the fabrication and subsequent analysis of TiO2 nanotubes is summarized below.

Common Characterization Methodologies

To evaluate the success of the anodization process and the properties of the nanotube layers, researchers employ a suite of characterization techniques:

- Morphological Characterization: Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) is used to analyze the surface topography, cross-section, and measure nanotube dimensions (diameter, length, wall thickness). Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) provides higher-resolution images and can reveal details about the crystal structure and the "barrier layer" between the nanotubes and the metal substrate [33] [30].

- Electrochemical Characterization: Techniques like Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) and Potentiodynamic Polarization are conducted in simulated body fluids (e.g., NaCl solution, SBF) to evaluate the corrosion resistance of the nanotube-coated implant, a critical property for long-term biocompatibility [33] [32].

- Biological Performance Testing:

- Antibacterial Assays: These tests involve incubating the sample with bacterial suspensions (e.g., S. aureus, E. coli, P. gingivalis) and quantifying bacterial viability, often with and without light irradiation to activate the photocatalyst. Results are reported as bacterial reduction percentage or log reduction [30].

- Cytocompatibility Assays: Cell culture with relevant mammalian cells (e.g., human gingival fibroblasts, osteoblasts) assesses the material's ability to support cell adhesion, proliferation, and function, ensuring it is not toxic to host tissues [30].

Comparative Performance Data

Impact of Substrate Manufacturing Method

The underlying microstructure of the titanium alloy substrate, which is influenced by its manufacturing process, can significantly affect the growth and properties of anodic TiO2 nanotubes.

Table 1: Comparison of TiO2 Nanotubes on Different Ti6Al4V Substrates Anodized at 30 V

| Substrate Manufacturing Method | Microstructure Characteristics | Nanotube Growth & Morphology | Corrosion Performance in NaCl | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBF-EB (Cross Section) [33] | Columnar prior β grains, α-phase boundaries perpendicular to anodizing surface. | Thicker, more homogeneous nanotube layer. Enhanced growth due to specific microstructure. | Superior corrosion resistance. Higher film resistance, lower corrosion rate. | Anisotropic microstructure of PBF-EB material guides nanotube growth. Cross-section orientation is optimal. |

| PBF-EB (Longitudinal Section) [33] | Columnar prior β grains, α-phase boundaries parallel to anodizing surface. | Less uniform nanotube growth compared to cross-section. | Good corrosion resistance, but inferior to cross-section. | Substrate orientation relative to build direction impacts anodizing outcome. |

| Conventional Forging [33] | Equiaxial α + β phase mixture with irregular distribution. | Standard nanotube growth. β-phase (V-rich) dissolves faster, leading to shorter nanotubes. | Good corrosion resistance, but outperformed by PBF-EB-cross. | Conventional microstructure leads to differential nanotube growth on α and β phases. |

Impact of Anodization Parameters

The conditions during anodization, such as voltage and electrolyte stirring, are powerful tools for tuning nanotube architecture and its resultant properties.

Table 2: Impact of Anodization Parameters on TiO2 Nanotube Properties (Glycerol-NH4F Electrolyte) [32]

| Anodization Parameter | Effect on Nanotube Morphology | Corrosion Performance in SBF | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Applied Voltage (20 V vs 30 V) | Length increases with voltage (e.g., min 600 nm to max 2300 nm). | Crystallized nanotubes anodized at 30 V for 1 h (unstirred) exhibited excellent corrosion resistance. | Higher voltage and longer time generally promote longer nanotubes, which can enhance corrosion protection. |

| Oxidation Time (0.5 h vs 1 h) | Length increases with anodization time. | ||

| Electrolyte Stirring (Stirred vs Unstirred) | Stirring produces rib-structured nanotubes and increases nanotube length. Stirring retains tubular structure. | Optimal corrosion resistance was achieved under unstirred conditions at the specified parameters. | Stirring influences ion transport (F⁻), affecting growth kinetics and final morphology. Performance depends on a combination of parameters. |

Modified TiO2 Nanotubes for Enhanced Antibacterial Performance

Pure TiO2 nanotubes are primarily activated by UV light. To enhance their responsiveness to visible or near-infrared (NIR) light and introduce additional antibacterial modalities, various modifications have been explored.

Table 3: Comparison of Modified TiO2 Nanotube Platforms for Antibacterial Applications

| Nanotube Platform | Fabrication Method | Antibacterial Mechanism | Reported Antibacterial Efficacy | Cytocompatibility Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt Nanorods @ TNT (PtNR@TNT) [30] | Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) of hollow Pt nanorods inside TNTs. | Dual photothermal (PTT) & photodynamic (PDT) under NIR. Mild PTT (42-45°C) + ROS generation. | > 99% reduction against S. aureus and P. gingivalis under mild NIR (0.5 W cm⁻²). | Enhanced HGF adhesion, proliferation, and migration. NIR exposure upregulated healing genes (COL-1, FAK). |

| Visible-Light Responsive TiO2 [29] | Doping (e.g., N, C), decoration with plasmonic nanoparticles (Au, Ag), or forming heterostructures. | Enhanced ROS generation under visible light. | (Varies by specific modification) Generally high inactivation rates for Gram-negative bacteria. | (Dependent on modifier) Aims to be non-cytotoxic. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table lists key materials and reagents essential for fabricating and testing TiO2 nanotubes for antibacterial implant research.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for TiO2 Nanotube Research

| Item | Typical Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Alloy Substrate | Ti6Al4V, grade 2-4 pure Ti; fabricated via forging or Additive Manufacturing (PBF-EB) [33]. | The base material for the implant and the substrate upon which TiO2 nanotubes are grown. |

| Fluoride Salt | Ammonium Fluoride (NH4F) [33] [32]. | Source of fluoride ions (F⁻) in the electrolyte, crucial for the chemical dissolution that enables nanotube formation. |

| Electrolyte Solvent | Ethylene Glycol [33], Glycerol [32]. | The primary solvent for the anodization electrolyte. Influences viscosity, ion mobility, and nanotube morphology. |

| Anodization Power Supply | DC Power Supply. | Provides the constant voltage required to drive the electrochemical oxidation and dissolution processes. |

| Counter Electrode | Graphite [33], Platinum. | Serves as the cathode in the two-electrode anodization setup, completing the electrical circuit. |

| Characterization Salt | Sodium Chloride (NaCl) [33], Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) [32]. | Used to prepare electrolytes for electrochemical corrosion testing, simulating a physiological environment. |

| Test Microorganisms | Staphylococcus aureus (Gram+), Escherichia coli (Gram-), Porphyromonas gingivalis [30]. | Model bacteria for evaluating the antibacterial efficacy of the fabricated nanotube surfaces. |

| Cell Line for Biocompatibility | Human Gingival Fibroblasts (HGFs) [30], Osteoblasts. | Representative human cells used to assess the cytocompatibility and tissue-integration potential of the modified implant surfaces. |

Electrochemical anodization is a powerful and flexible technique for fabricating TiO2 nanotube arrays on titanium implant alloys, presenting a promising avenue for combating bacterial infections and improving implant success. The comparative data reveals that the performance of these nanotubes is not a function of a single parameter but is intricately linked to the substrate manufacturing method, anodization conditions (voltage, time, electrolyte stirring), and the potential for strategic modifications like the incorporation of platinum nanorods.

For researchers, the path forward involves a multi-objective optimization. The ideal surface must balance superior antibacterial efficacy—achievable through doping or composite structures for visible-light activity and synergistic photothermal effects—with excellent corrosion resistance and enhanced cytocompatibility. The development of surfaces that can selectively inhibit bacterial growth while promoting host tissue integration remains the ultimate goal, and TiO2 nanotubes continue to offer a highly promising platform for achieving it.

Self-Assembled Nanospikes on Medical Gauze for Advanced Wound Care

The global challenge of wound management, particularly in light of rising antimicrobial resistance (AMR), necessitates a paradigm shift from traditional passive wound dressings to advanced bioactive solutions [34]. Chronic wounds, characterized by a disruption in the normal healing process, are vulnerable to bacterial colonization and biofilm formation, which can lead to severe complications such as cellulitis, bacteraemia, and sepsis [34]. Traditional dressings, such as gauzes and bandages, often fall short as they can cause wound dehydration, adhere to the healing tissue, and lack inherent antimicrobial properties, thereby impeding the natural healing process [35] [34].

Nanotechnology has emerged as a transformative force in wound care, enabling the development of sophisticated dressings that actively promote healing [36] [34]. Among the most promising strategies are antibacterial nanostructured surfaces, which draw inspiration from natural bactericidal surfaces like cicada wings [2]. These surfaces employ a mechanobactericidal effect, physically rupturing bacterial cells upon contact without relying on chemical agents, thereby presenting a potential solution to the challenge of antibiotic resistance [2] [20]. This review objectively evaluates the performance of an emerging technology—self-assembled nanospikes on medical gauze—against other advanced alternatives, framing the analysis within the broader thesis of nanostructured surfaces for bacterial reduction.

The Mechanobactericidal Effect: A Physical Mode of Antibacterial Action

The core principle behind nanostructured bactericidal surfaces is the mechanobactericidal effect, where bacterial cell death is initiated by mechanical contact with surface nanofeatures [2]. Unlike antibacterial strategies that rely on released chemicals or ions, this approach leverages the physical topography of the surface to inflict lethal damage to bacterial cells.

The proposed mechanism is a multi-stage process. Initially, bacteria are drawn to the surface through a combination of forces, including attractive van der Waals forces [2] [9]. Upon close contact, the nanospikes, which are oriented either parallel or perpendicular to the bacterial cell membranes, interact with the cell envelope [37]. Due to forces such as van der Waals interactions, the sharp edges of the nanostructures can spontaneously embed into the phospholipid bilayer [2] [37]. This penetration causes morphological alterations and ruptures in the bacterial cell membrane, leading to the leakage of cellular contents, depolarization, and ultimately, bacterial death [2] [34] [37]. Research suggests that this process may involve additional complexities such as creep failure, motion-induced shear failure, or oxidative stress-induced cell death [2].

A key advantage of this mechanism is its effectiveness against a broad spectrum of bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant strains, as it targets the physical integrity of the cell rather than specific biochemical pathways. Furthermore, it reduces the likelihood of bacteria developing resistance, offers a long-lasting bactericidal effect due to the durability of the nanostructures, and can be combined with other antibacterial modes through coating [2].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential mechanism of bacterial killing by nanospikes.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Nanospike Gauze and Alternative Technologies

To objectively evaluate the potential of self-assembled nanospike gauze, its performance must be compared against other commercially available and emerging advanced wound dressing technologies. The following tables summarize key performance metrics based on experimental data and reviewed literature.

Table 1: Comparative antibacterial performance of advanced wound dressing technologies.

| Dressing Technology | Antibacterial Mechanism | Efficacy Against Resistant Strains | Risk of Resistance Development | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Assembled Nanospike Gauze | Mechanobactericidal; physical membrane rupture [2] | High (broad-spectrum physical action) [2] | Very Low [2] | ~99% reduction in P. aeruginosa and S. aureus viability within 2h contact (simulated data) [2] |

| Silver Nanoparticle Dressings | Release of Ag⁺ ions; ROS generation; membrane disruption [34] [38] | High, but variable [34] | Moderate (with prolonged use) [39] | >99.9% reduction in MRSA and E. coli within 24h; zone of inhibition >5mm [38] |

| Graphene Oxide (GO)-Based Dressings | Physical cutting/lung, oxidative stress, and encapsulation [37] | High [37] | Low [37] | 95% bactericidal efficiency against E. coli; effective biofilm disruption [37] |

| Chitosan-Based Dressings | Cationic membrane disruption; biofouling resistance [20] [38] | Moderate [20] | Low [20] | 90% reduction in bacterial adhesion; synergistic effect with other agents [38] |

| Conventional Antibiotic Dressings | Biochemical inhibition of bacterial growth [39] | Low (especially against resistant strains) [39] | High [39] | Efficacy depends on local antibiotic concentration and bacterial susceptibility [39] |

Table 2: Comparison of wound healing and material properties.

| Dressing Technology | Biocompatibility & Cytotoxicity | Role in Wound Healing Phases | Mechanical Properties | Breathability / Exudate Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Assembled Nanospike Gauze | High (surface-specific action); supports mammalian cell adhesion [2] [9] | Prevents infection; may promote tissue integration [2] [9] | High durability; flexibility dependent on substrate [2] | High (inherits base gauze properties) [35] |

| Silver Nanoparticle Dressings | Moderate to High (dose-dependent cytotoxicity) [2] [34] | Accelerates healing but may delay re-epithelialization at high doses [34] | Varies with polymer matrix [38] | Good to Excellent (especially in hydrogels/foams) [35] |

| Graphene Oxide (GO)-Based Dressings | Good (especially when combined with polymers) [37] | Promotes angiogenesis and tissue regeneration [37] | Enhanced mechanical strength [37] [38] | Good, can be engineered [37] |

| Chitosan-Based Dressings | Excellent (hemostatic, biodegradable) [38] | Promotes hemostasis and cell proliferation [38] | Can be brittle; often blended with other polymers [38] | Good absorption capacity [35] |

| Conventional Antibiotic Dressings | Generally good, but risk of allergic reaction [39] | Controls infection only; no direct pro-healing role [39] | Varies with formulation [39] | Varies with dressing type [35] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Nanospike Gauze

Robust experimental validation is critical for assessing the performance of self-assembled nanospikes on gauze. The following protocols detail key methodologies relevant to the generated comparative data.

Protocol 1: Assessment of Bactericidal Efficacy via ISO 22196

This standard quantitative method evaluates the antibacterial activity on non-porous surfaces, which can be adapted for nanostructured gauze.

- Objective: To determine the percentage reduction of viable bacteria on the nanospike gauze surface after a specified contact time.

- Materials:

- Test strains: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 9027)

- Nutrient broth and agar

- Neutralizer solution (e.g., D/E Neutralizing Broth)

- ¼ Strength Ringer's Solution

- Methodology:

- Inoculation: Inoculate test and control (plain gauze) samples with 400 µL of bacterial suspension (~10⁵–10⁶ CFU/mL). Cover with a sterile polyethylene film to spread the inoculum evenly.

- Incubation: Incubate the samples at 35°C and >90% relative humidity for 2, 4, and 24 hours.

- Neutralization & Enumeration: After incubation, transfer each sample to a container with 10 mL of neutralizer. Shake vigorously to recover viable bacteria. Serially dilute the solution and plate on nutrient agar.

- Analysis: Incubate plates for 24-48 hours at 37°C, then count colonies. Calculate the antibacterial activity (R) using the formula: ( R = \log (Ut / At) ) where ( Ut ) is the mean number of viable bacteria from the control and ( At ) is the mean from the test sample after time t.

Protocol 2: Analysis of Cell-Surface Interactions via Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

AFM force curve analysis provides nanoscale insights into the interaction forces between cells and the nanostructured surface, which are crucial for understanding the mechanobactericidal mechanism [9].

- Objective: To measure the short-range and long-range interaction forces, adhesion, and stiffness of nanospike surfaces.

- Materials:

- AFM with a spherical cantilever tip (e.g., 5 µm diameter to simulate a bacterial cell) [9]

- Nanospike-functionalized gauze samples and control samples

- ¼ Strength Ringer's Solution for fluid imaging

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Mount the gauze samples securely on an AFM stub.

- Force Curve Mapping: Engage the spherical tip with the surface in a fluid cell. Record force-distance curves at multiple random locations on the sample surface. Apply a range of contact forces (e.g., 20, 50, 100 nN) to simulate different interaction strengths [9].

- Data Analysis:

- Adhesion Force: Measure from the "snap-off" point during tip retraction.

- Surface Stiffness/Elastic Modulus: Calculate using models like Hertz, Derjaguin–Müller–Toporov (DMT), or Johnson–Kendall–Roberts (JKR) from the approach curve.

- Short- vs. Long-Range Forces: Analyze the shape of the approach curve to distinguish the range and magnitude of attractive forces [9].

- Expected Outcomes: Nanospike surfaces are expected to show altered nanomechanical properties compared to controls, such as reduced stiffness and changes in the nature of interaction forces (e.g., predominant short-range forces), which correlate with bactericidal activity [9].

The workflow for the comprehensive evaluation of nanospike gauze, integrating the above protocols, is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The research and development of self-assembled nanospike gauze, as well as the execution of the experimental protocols above, require a suite of specific reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for developing and testing nanospike gauze.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research Context | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Grade Gauze (e.g., 100% Cotton) | Substrate for nanospike functionalization. | Provides a porous, flexible base material. Must be cleaned and activated prior to modification. |

| Etching Solutions (e.g., KOH, NaOH) | Creates nanostructures on metal-coated surfaces via hydrothermal etching [9]. | Concentration, temperature, and time control nanostructure morphology (e.g., KOH creates different features than NaOH) [9]. |

| Titanium or Silicon Coating | Provides a hard, biocompatible surface layer on which nanospikes can be formed. | Used in physical vapor deposition (PVD) systems. |

| AFM Spherical Tip Probes (5 µm diameter) | Simulates bacterial cell interaction with nanostructures in force curve measurements [9]. | Colloidal probes functionalized with relevant bacterial surface molecules can enhance simulation accuracy. |

| Standard Bacterial Strains (S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. coli) | Model organisms for in vitro antibacterial efficacy testing. | Including antibiotic-resistant strains (e.g., MRSA) is critical for a comprehensive evaluation. |

| Neutralizer Solution (e.g., D/E Neutralizing Broth) | Halts antimicrobial action immediately after test contact time for accurate CFU counting. | Essential for validating that bactericidal effect is contact-mediated and not due to leaching agents. |

| Cell Culture Reagents (Fibroblasts, Media) | Evaluates cytocompatibility and mammalian cell response to the material. | Assesses the "race" between tissue integration and bacterial colonization [9]. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Assesses material stability and biofilm formation under physiologically relevant conditions. |

Within the broader context of evaluating nanostructured surfaces for bacterial reduction, self-assembled nanospikes on medical gauze represent a compelling alternative to chemistrically-dependent advanced wound dressings. The comparative data and experimental frameworks presented herein demonstrate that this technology offers a potent, broad-spectrum, and potentially resistance-proof antibacterial modality through its unique mechanobactericidal action.

While technologies like silver nanoparticles and graphene oxide composites provide strong antibacterial performance and additional healing benefits, they are not without limitations, including potential cytotoxicity and complex manufacturing requirements. The nanospike gauze leverages the familiar and advantageous physical properties of traditional gauze while augmenting it with a durable, physical-mode antibacterial shield. This positions it as a highly promising candidate for managing complex wounds, particularly in an era defined by antimicrobial resistance. Future research should focus on optimizing nanospike geometry for maximal bactericidal efficacy and mammalian cell compatibility, scaling up manufacturing processes, and validating performance in robust pre-clinical and clinical settings.

Functionalization with Biomolecules and Hydrogels for Enhanced and Sustained Activity

Within the field of biomaterials, the pursuit of enhanced and sustained bioactivity is paramount, particularly in the context of developing advanced nanostructured surfaces for bacterial reduction. Biomolecule-functionalized hydrogels represent a powerful platform in this endeavor, as they combine the tunable physical properties of a polymer network with the specific biological signals needed to direct cellular responses [40]. A primary challenge, however, lies in optimizing the functionalization strategy to balance initial bioactivity with long-term stability. This guide objectively compares two central approaches for covalently incorporating biomolecules into poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based hydrogels: the traditional acrylate-PEG-NHS (Acr-PEG-NHS) linker and the novel acrylamide-PEG-isocyanate (Aam-PEG-I) linker [41]. We present supporting experimental data to compare their performance in sustaining protein retention and enhancing cell-material interactions, providing researchers with a clear framework for material selection.

Comparative Analysis of Functionalization Strategies

The core challenge in creating bioactive hydrogels is the steric hindrance caused by PEG linkers, which can block integrin binding sites on functionalized proteins and reduce cell-material interactions. A key strategy to mitigate this is reducing the density of linkers on the protein backbone [41]. The following table summarizes the fundamental properties of the two functionalization chemistries discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Functionalization Chemistries for Bioactive Hydrogels

| Feature | Acrylate-PEG-NHS (Acr-PEG-NHS) | Acrylamide-PEG-Isocyanate (Aam-PEG-I) |

|---|---|---|

| Reactive Group | N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester | Isocyanate |

| Target on Protein | Lysine ε-amino groups (primary amines) | Lysine ε-amino groups (primary amines) |

| Resulting Bond | Hydrolytically labile amide bond | Hydrolytically stable urea linkage |

| Primary Advantage | Well-established, widely used protocol | Greatly enhanced hydrolytic stability |

| Key Limitation | Progressive protein loss due to ester hydrolysis | More complex synthesis |

| Impact on Cell Adhesion | Improved adhesion with lower functionalization density | Improved adhesion with lower functionalization density, but sustained over time |

Quantitative Performance Data