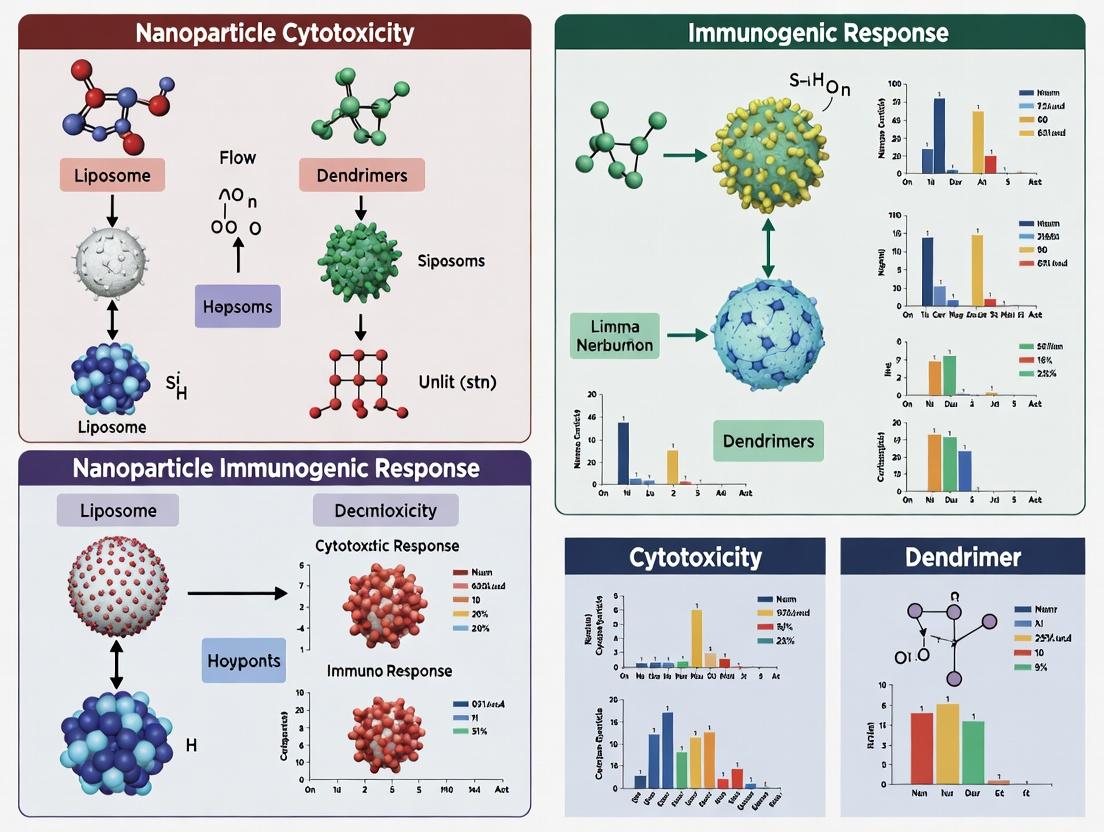

Navigating the Double-Edged Sword: A Comprehensive Guide to Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity and Immunogenic Response for Advanced Therapeutics

This article provides a detailed scientific and technical analysis of nanoparticle-induced cytotoxicity and immunogenicity, critical challenges in nanomedicine development.

Navigating the Double-Edged Sword: A Comprehensive Guide to Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity and Immunogenic Response for Advanced Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a detailed scientific and technical analysis of nanoparticle-induced cytotoxicity and immunogenicity, critical challenges in nanomedicine development. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content explores the foundational mechanisms of nanotoxicity, outlines robust in vitro and in vivo assessment methodologies, offers strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing nanoparticle design to mitigate adverse responses, and compares validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to balance therapeutic efficacy with biocompatibility, accelerating the translation of safer nanotherapeutics into clinical applications.

Understanding the Roots of Nanotoxicity: Core Mechanisms Driving Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity and Immunogenicity

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity Assays

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Inconsistent ROS Detection Results

- Symptom: High variability in fluorescent signal (e.g., DCFH-DA, DHE) between replicates.

- Common Causes & Solutions:

- Nanoparticle Interference: Some NPs quench fluorescence or auto-oxidize the probe.

- Action: Include a control where dye is incubated with NPs but not cells. Use plate readers with rapid kinetic cycles.

- Uneven Nanoparticle Settling: Leads to varying cellular dose.

- Action: Standardize plate rocking during incubation or use well-characterized dispersion protocols (e.g., with serum albumin).

- Probe Overloading/Photobleaching: Inaccurate measurement.

- Action: Titrate dye concentration; reduce exposure time during imaging.

- Nanoparticle Interference: Some NPs quench fluorescence or auto-oxidize the probe.

Guide 2: Poor Membrane Integrity Assay Reproducibility

- Symptom: High background or low signal in LDH release or PI uptake assays.

- Common Causes & Solutions:

- NP-Enzyme/Assay Interference: NPs can adsorb LDH enzyme or react with assay components.

- Action: Always include an NP-only control with assay reagents. Centrifuge samples thoroughly to pellet NPs before LDH assay.

- Serum Enzyme Contamination: FBS contains endogenous LDH.

- Action: Wash cells thoroughly with PBS before assay initiation. Use low-serum or serum-free media during NP exposure.

- Timing Issues: Membrane damage may be transient or late.

- Action: Perform time-course experiments (e.g., 4, 8, 24h).

- NP-Enzyme/Assay Interference: NPs can adsorb LDH enzyme or react with assay components.

Guide 3: Weak or No Genotoxicity Signal

- Symptom: Low γ-H2AX foci count or comet tail moment despite evidence of oxidative stress.

- Common Causes & Solutions:

- Insufficient Damage or Repair: Damage may be below detection threshold or rapidly repaired.

- Action: Optimize NP dose and exposure time. Consider using repair inhibitors (e.g., PARP inhibitors for base excision repair) as a positive control.

- Fixation/Permeabilization Issues: Antibodies cannot access nuclear antigens.

- Action: Validate protocol with a known genotoxicant (e.g., etoposide, H₂O₂). Titrate Triton X-100 concentration.

- NP-Induced Artifacts in Comet Assay: NPs can cause physical DNA dragging.

- Action: Run an NP-only gel to check for "comet-like" artifacts. Use enzymes (e.g., FPG) to detect specific oxidation.

- Insufficient Damage or Repair: Damage may be below detection threshold or rapidly repaired.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose the most relevant assay for detecting NP-induced oxidative stress? A: The choice depends on the ROS type and compartment. Use a panel:

- General ROS: DCFH-DA (cytosolic).

- Superoxide: Dihydroethidium (DHE) with HPLC validation for specificity.

- Mitochondrial ROS: MitoSOX Red.

- Glutathione depletion: Monochlorobimane assay.

- Always confirm with a direct antioxidant (e.g., N-acetylcysteine) rescue experiment.

Q2: Our nanoparticles aggregate heavily in cell culture media, skewing dose-response. How can we improve dispersion? A: Standardized dispersion is critical.

- Pre-disperse NPs in sterile 0.1-1% BSA or serum-free media via probe sonication (calibrated energy/time, ice bath).

- Immediately add this stock to complete culture media with serum. Serum proteins act as biocoronas, stabilizing dispersion.

- Characterize the hydrodynamic diameter and PDI in the exact exposure medium using dynamic light scattering (DLS). Report this as the administered dose metric.

Q3: What are the critical controls for proving NP-induced genotoxicity is specific? A: Essential controls include:

- Negative Control: Untreated cells & dispersion media control (e.g., BSA in media).

- Positive Control: Known genotoxicant (e.g., 50 µM Etoposide for 4h for γ-H2AX).

- Nanomaterial Controls: i) Internalized but inert material (e.g., silica-coated non-reactive NPs) to check for physical interference. ii) NP + potent antioxidant (NAC) to link genotoxicity to ROS.

- Sham Control: For magnetic/light-activated NPs, apply the activating field without NPs.

Q4: How can we distinguish between primary (direct) and secondary (inflammation-mediated) genotoxicity? A: Implement a co-culture or conditioned media approach.

- Treat immune cells (e.g., THP-1 macrophages) with NPs.

- After 24h, collect the conditioned media, centrifuge to remove NPs, and apply to target cells (e.g., epithelial cells).

- Compare genotoxicity in target cells from direct NP exposure vs. conditioned media exposure. An effect from conditioned media indicates secondary, inflammation-driven damage.

Table 1: Common Assays for Nanoparticle-Induced Damage Pathways

| Damage Pathway | Key Assays | Readout | Typical Positive Control | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Stress | DCFH-DA fluorescence | General ROS | 100-500 µM tert-Butyl hydroperoxide | Dye auto-oxidation, NP quenching |

| DHE/HPLC | Superoxide (O₂⁻) | Antimycin A (1-10 µM) | Non-specific oxidation to ethidium | |

| GSH/GSSG ratio | Redox state | Diamide (1 mM) | Rapid auto-oxidation of samples | |

| Membrane Disruption | LDH release | Cytotoxicity | 1% Triton X-100 | Serum LDH, NP interference |

| Propidium Iodide uptake | Membrane permeability | 70% Ethanol | NP auto-fluorescence | |

| Annexin V/PI staining | Apoptosis/Necrosis | Staurosporine (1 µM) | Timing-dependent results | |

| Genotoxicity | γ-H2AX foci microscopy | DNA double-strand breaks | Etoposide (50 µM, 4h) | Foci counting subjectivity |

| Alkaline Comet Assay | DNA strand breaks | Methyl methanesulfonate (100 µM) | NP-induced dragging artifacts | |

| Micronucleus (Cytokinesis-block) | Chromosomal damage | Mitomycin C (0.1 µg/mL) | Inadequate cytochalasin B concentration |

Table 2: Example Dose-Response Data for Common Nanomaterials (In Vitro)

| Nanomaterial | Size (nm) | Cell Line | Oxidative Stress (EC₅₀, µg/mL) | Membrane Damage (EC₅₀, µg/mL) | Genotoxicity (Lowest Observed Effect Level, µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrate-capped Ag NPs | 20 | A549 | 5-10 (DCF) | 10-15 (LDH) | 2.5 (γ-H2AX) |

| TiO₂ (Anatase) NPs | 30 | BEAS-2B | 50-100 (DHE) | >200 (LDH) | 50 (Comet Assay) |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes | 10x5000 | THP-1 | 20-50 (DCF) | 50-100 (LDH) | 10 (Micronucleus) |

| Polymer-coated ZnO NPs | 50 | HepG2 | 5-15 (MitoSOX) | 10-20 (LDH) | 5 (γ-H2AX) |

EC₅₀: Half-maximal effective concentration. Data is representative and highly dependent on surface modification, dispersion, and cell type.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Nanoparticle Dispersion for Cell Exposure

- Weigh NP powder in a sterile tube.

- Add sterile 0.1% BSA in PBS (or serum-free medium).

- Sonicate using a probe sonicator (e.g., 30% amplitude, 5 min, pulsed 1s on/1s off) on ice to prevent heating.

- Dilute the stock immediately into complete cell culture medium to the highest treatment concentration.

- Serially dilute in complete medium to create dose range. Vortex each dilution briefly.

- Characterize the primary dose solution (hydrodynamic size, PDI, zeta potential) via DLS.

Protocol 2: Intracellular ROS Measurement using DCFH-DA

- Seed cells in a black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well plate.

- Treat with NPs for desired time.

- Wash cells with PBS.

- Load with 10 µM DCFH-DA in serum-free, phenol-red-free medium for 30 min at 37°C.

- Wash 3x with PBS to remove extracellular dye.

- Add fresh phenol-red-free medium and immediately read fluorescence (Ex/Em: 485/535 nm) on a plate reader, taking kinetic readings every 5-10 min for 1h.

- Normalize fluorescence to protein content (e.g., via Bradford assay).

Protocol 3: Cytokinesis-Block Micronucleus Assay

- Seed cells (e.g., CHO, HepG2) in 6-well plates and allow to attach.

- Treat with NPs for 24h.

- Add Cytochalasin B (final conc. 3-6 µg/mL) to block cytokinesis.

- Continue incubation for an additional 28h (total cytochalasin B exposure: 28h).

- Harvest cells by trypsinization, hypotonic treatment (0.075 M KCl), and fix in 3:1 methanol:acetic acid.

- Drop cells onto slides, air dry, and stain with Giemsa or DNA-specific dye (e.g., DAPI).

- Score micronuclei in binucleated cells only (minimum 1000 BN cells per treatment).

Visualization: Pathways & Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Primary Function in NP Toxicity Studies |

|---|---|---|

| DCFH-DA / CM-H2DCFDA | Thermo Fisher, Sigma-Aldrich | Cell-permeable probe for general intracellular ROS detection. |

| MitoSOX Red | Thermo Fisher | Mitochondria-targeted fluorogenic dye for superoxide detection. |

| CellTox Green Cytotoxicity Assay | Promega | Real-time, fluorescent dye that stains DNA of dead cells (membrane-compromised). |

| Cytokine Profiling ELISA/Multiplex Array | R&D Systems, Bio-Rad | Quantifies secreted inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) indicating immunogenic response. |

| γ-H2AX (phospho-S139) Antibody | MilliporeSigma, Cell Signaling | Gold-standard immunofluorescence marker for DNA double-strand breaks. |

| CometAssay Kit | Trevigen, Abcam | All-in-one kit for standardized single-cell gel electrophoresis (alkaline or neutral conditions). |

| Recombinant Human Albumin (rHA) | Novozymes, Sigma | Protein source for NP dispersion without batch variability of serum-derived BSA. |

| N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) | Sigma-Aldrich | Broad-spectrum antioxidant used in rescue experiments to confirm ROS-mediated effects. |

| Cytochalasin B | Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris | Inhibitor of actin polymerization; essential for cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay. |

| Zeta Potential Reference Standard | Malvern Panalytical | Calibration standard for accurate surface charge measurement of NPs in suspension. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Category 1: Protein Corona & Characterization Issues

Q1: Our DLS measurements show highly variable hydrodynamic sizes after incubating nanoparticles (NPs) in plasma. What could be causing this inconsistency?

- A: Inconsistent protein corona formation is the likely cause. Ensure the plasma/serum source and concentration are identical across replicates. Pre-incubation temperature and time must be rigorously controlled (e.g., 37°C for 60 min). Filter the biological fluid through a 0.22 µm filter before use to remove aggregates. Always use a consistent vortexing or mixing protocol post-incubation before DLS measurement.

Q2: SDS-PAGE of the hard corona shows smearing instead of distinct bands. How can we improve resolution?

- A: Smearing indicates incomplete elution or protein degradation. Optimize your elution buffer: increase SDS concentration to 4%, add a chaotropic agent (2M urea), and boil samples for 10 minutes, not 5. Ensure you are centrifuging at 100,000 x g for 1 hour at 4°C to firmly pellet NPs with the hard corona before washing. Overloading the gel can also cause smearing; try serial dilutions of your eluate.

Category 2: Inflammasome Activation & Cell Assays

Q3: We cannot detect significant IL-1β release from THP-1 macrophages despite using a known inflammasome activator (e.g., LPS + nigericin) as a positive control.

- A: First, confirm your THP-1 differentiation protocol. Cells must be treated with 100 nM PMA for 48-72 hours, followed by a 24-hour rest period in standard medium for proper maturation into macrophages. For canonical NLRP3 priming, use 10-100 ng/mL Ultrapure LPS for 3-4 hours. The activator (e.g., NPs) must then be added for a sufficient duration (6-24h). Always measure cell viability (LDRAssay) concurrently, as high cytotoxicity can paradoxically reduce IL-1β release.

Q4: Our negative control (PBS) is showing background caspase-1 activity in our FLICA assay.

- A: This is typically due to residual FLICA reagent. Increase the number of post-staining washes from 2 to 4 using the provided apoptosis wash buffer. Ensure you are using a plate reader with appropriate filters (Ex/Em ~492/520 nm for FAM-FLICA). Prepare a "No FLICA" control for each condition to autofluorescence.

Category 3: Complement Activation

Q5: Our ELISA for complement activation fragment C3a shows high background in all samples, including buffer-only controls.

- A: Human serum is rich in pre-formed C3a. You must use serum that has been freshly prepared and aliquoted, never previously freeze-thawed more than twice. Run a "serum-only" control (serum + buffer) and subtract its value from your NP-treated samples to calculate NP-specific activation. Ensure your stop solution is added at the exact time specified in the protocol.

Q6: How do we differentiate between the classical, lectin, and alternative pathway activation by our NPs?

- A: You need pathway-specific functional assays. Use cation depletion (Ca²⁺ chelation with EGTA blocks classical/lectin, leaving alternative) or pathway-specific complement-deficient sera (e.g., C1q-, C2-, or Factor B-deficient). Measure the endpoint (e.g., C5a generation, CH50) in these conditions versus normal human serum. See Table 2 for a summary.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation and Analysis of the Hard Protein Corona

- Incubation: Incubate 1 mg/mL of NPs in 50% (v/v) human serum in PBS (total vol 1 mL) at 37°C for 1 hour with gentle rotation.

- Separation: Ultracentrifuge the mixture at 100,000 x g for 60 minutes at 4°C.

- Wash: Carefully discard supernatant. Resuspend pellet in 1 mL of ice-cold PBS. Repeat ultracentrifugation step twice.

- Elution: Resuspend final pellet in 100 µL of 2x Laemmli buffer (with 4% SDS and 5% β-mercaptoethanol). Boil for 10 minutes at 95°C.

- Analysis: Centrifuge at 16,000 x g for 5 min. Load supernatant onto a 4-20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel. Perform Coomassie staining or western blot for proteins of interest (e.g., IgG, albumin, fibrinogen, apolipoproteins).

Protocol 2: Assessing NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Primed Macrophages

- Cell Preparation: Differentiate THP-1 cells in 96-well plates (10⁵ cells/well) with 100 nM PMA for 48h. Rest for 24h in fresh RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS.

- Priming: Prime cells with 100 ng/mL Ultrapure LPS in serum-free medium for 3 hours.

- Activation: Treat primed cells with NPs (a range of 10-100 µg/mL) or controls (5 µM nigericin for positive, PBS for negative) for 6 hours.

- Analysis: Collect supernatant. Measure IL-1β via ELISA. In parallel, assay for cytotoxicity using LDH release. For intracellular caspase-1, use a FLICA assay according to manufacturer instructions.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Protein Corona Components and Their Implications

| Protein Identified | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Abundance Rank (Typical) | Potential Immunogenic Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Serum Albumin | 66.5 | 1 (High) | Can mask NP surface, reducing recognition ("stealth effect"). |

| Immunoglobulin G (IgG) | 150 | 2-3 (Medium-High) | Opsonization; can engage Fc receptors on immune cells. |

| Fibrinogen | 340 | Variable (Medium) | Potent activator of macrophages via Mac-1 integrin. |

| Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) | 34 | Variable (Low-Medium) | Influences hepatic clearance and cellular uptake. |

| Complement C3 | 185 | Variable (Low) | Presence indicates complement activation potential. |

Table 2: Key Assays for Immunogenicity Profiling

| Assay Target | Example Assay | Key Readout | Typical Values for "Positive" Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Corona | SDS-PAGE / LC-MS | Protein band intensity / # of unique IDs | ~30-100 distinct proteins identified. |

| Inflammasome Activation | IL-1β ELISA (cell supernatant) | Concentration (pg/mL) | Nigericin: >500 pg/mL vs. PBS: <20 pg/mL. |

| Complement Activation | C3a Des Arg ELISA (serum) | Concentration (ng/mL) | Zymosan (100 µg/mL): >2000 ng/mL increase over serum baseline. |

| Cell Viability | LDH Release | % Cytotoxicity | Triton X-100 (1%): ~95-100% cytotoxicity. |

Diagrams

Diagram 1: NP Immunogenicity Pathways Overview

Title: Three Key Pathways of Nanoparticle Immunogenicity

Diagram 2: NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation Workflow

Title: Stepwise NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by NPs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Immunogenicity Research |

|---|---|

| Ultrapure Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Standard agonist for "priming" the NLRP3 inflammasome via TLR4. Ensures activation is specific to Signal 2. |

| Nigericin (or ATP) | Positive control for NLRP3 inflammasome activation (induces K+ efflux). Validates assay functionality. |

| Human AB Serum (Pooled) | Standardized serum source for in vitro protein corona and complement studies, reducing donor variability. |

| EGTA/Mg²⁺ Buffer | Selective chelator (EGTA binds Ca²⁺, not Mg²⁺). Used to inhibit Classical/Lectin complement pathways. |

| Pathway-Specific Complement-Deficient Sera (e.g., C1q-, Factor B-) | Critical for identifying the specific complement activation pathway (Classical vs. Alternative). |

| FLICA Caspase-1 Assay Kit (FAM-YVAD-FMK) | Fluorescent probe for in situ detection of active caspase-1 in live cells. |

| LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit | Essential parallel measurement to distinguish specific immune activation from general cell death. |

| Polymeric NPs (e.g., PS, PLGA) | Common benchmark/control particles with well-characterized surface chemistry for comparison. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: My nanoparticles are aggregating in biological media (e.g., cell culture medium, serum). How can I improve their colloidal stability? A: Aggregation is commonly due to high ionic strength neutralizing surface charge or hydrophobic interactions. To troubleshoot:

- Check Surface Charge (Zeta Potential): Measure the zeta potential in your biological media, not just in water. A value between -30 mV and +30 mV indicates instability. A magnitude > |30| mV suggests good electrostatic stability.

- Assess Hydrophobicity: Use hydrophobic interaction chromatography or dye-binding assays (e.g., Rose Bengal). High hydrophobicity leads to protein corona formation and aggregation.

- Solutions:

- Increase Steric Stabilization: Coat nanoparticles with polyethylene glycol (PEG), polysorbate 80, or other polymers.

- Optimize Surface Charge: For cationic particles causing serum protein aggregation, consider modifying with anionic or neutral coatings.

- Use Freshly Prepared Suspensions: Sonicate particles immediately before use and avoid long incubation times in complex media.

Q2: I am observing unexpectedly high cytotoxicity. Which physicochemical parameter should I investigate first? A: Surface charge is often the primary culprit for acute cytotoxicity, especially cationic charge.

- Primary Investigation: Measure the zeta potential of your nanoparticles in the relevant biological buffer. Strongly cationic surfaces (e.g., > +20 mV) can disrupt cell membranes via electrostatic interactions.

- Secondary Investigation: Evaluate size. Very small nanoparticles (< 5 nm) can cause toxicity by penetrating organelles and generating reactive oxygen species (ROS).

- Protocol: LDH Release Assay for Membrane Damage:

- Seed cells in a 96-well plate.

- Treat with nanoparticle samples and controls for 24h.

- Centrifuge plate, transfer supernatant to a new plate.

- Add LDH assay reagent (containing lactate, INT, diaphorase, NAD+) and incubate for 30 min.

- Measure absorbance at 490 nm and 680 nm (reference). High LDH release correlates with membrane damage from charged or sharp nanoparticles.

Q3: My nanoparticles are not being internalized by the target immune cells (e.g., macrophages). What could be the issue? A: This is likely governed by size, shape, and surface properties.

- Size: For phagocytosis by macrophages, optimal particle size is 1-3 µm. Nanoparticles (< 200 nm) may require opsonization or specific targeting ligands.

- Shape: Macrophages internalize spherical particles more efficiently than high-aspect-ratio rods or fibers.

- Surface Hydrophobicity/Charge: Hydrophobic and charged surfaces are more readily opsonized and recognized by scavenger receptors.

- Experiment to Test: Perform a flow cytometry-based uptake assay using fluorescently labeled nanoparticles. Pre-treat cells with inhibitors for different pathways (e.g., cytochalasin D for phagocytosis, chlorpromazine for clathrin-mediated endocytosis) to determine the entry mechanism.

Q4: How do I systematically test the immunogenic potential (e.g., NLRP3 inflammasome activation) of my nanoparticle library? A: Inflammasome activation is highly sensitive to particle size, shape, and hydrophobicity.

- Key Assay: IL-1β secretion ELISA from primary human macrophages. NLRP3 activation leads to pro-IL-1β cleavage and secretion.

- Required Controls: Use LPS priming (signal 1) alone, ATP (a known NLRP3 activator) as a positive control, and a negative control nanoparticle (e.g., plain PEG-coated).

- Expected Trends: Needle-like shapes, crystalline structures (e.g., silica), and hydrophobic surfaces are potent activators. Small spherical, smooth, hydrophilic particles are typically less activating.

Table 1: Impact of Physicochemical Properties on Biological Responses

| Determinant | Typical Range Tested | Key Biological Response | Experimental Readout |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | 5 nm - 200 nm (drug delivery) | Cellular uptake efficiency, biodistribution, renal clearance | Flow cytometry (% positive cells), ICP-MS (tissue accumulation) |

| 0.5 µm - 3 µm (vaccines) | Phagocytosis, inflammasome activation | Confocal microscopy, IL-1β ELISA | |

| Shape | Spheres, Rods (AR 1-8), Disks | Cell entry mechanism, circulation time, immunogenicity | Inhibitor studies, IVIS imaging, cytokine array |

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) | -50 mV to +50 mV | Serum stability, cytotoxicity, protein corona composition | DLS, LDH/MTS assay, proteomics |

| Hydrophobicity | Log P, Contact Angle | Protein adsorption, clearance by MPS, inflammatory response | HIC, 2D-DIGE, neutrophil recruitment in vivo |

Table 2: Common Characterization Techniques

| Parameter | Primary Technique(s) | Sample Preparation Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic Size & PDI | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Always measure in the same medium used for biological tests. Filter samples (0.22 µm). |

| Shape & Morphology | Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Use compatible grids (e.g., carbon-coated), stain if necessary (uranyl acetate). |

| Surface Charge | Zeta Potential (Laser Doppler Velocimetry) | Use appropriate electrolyte concentration (e.g., 1 mM KCl) and pH adjustment. |

| Surface Hydrophobicity | Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) | Use a phenyl or butyl column with a descending salt gradient. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Protein Corona Composition Objective: To identify proteins adsorbed onto nanoparticles from biological fluids. Materials: Nanoparticles, complete cell culture medium with 10% FBS, ultracentrifuge, SDS-PAGE/western blot or LC-MS/MS reagents. Steps:

- Incubate nanoparticles (100 µg/mL) in complete medium at 37°C for 1h.

- Centrifuge at 100,000 x g for 1h at 4°C to pellet nanoparticle-protein corona complexes.

- Carefully remove supernatant and wash pellet gently with cold PBS. Repeat centrifugation.

- Resuspend pellet in Laemmli buffer for SDS-PAGE/western blot analysis of specific proteins (e.g., ApoE, albumin, immunoglobulins) or in urea buffer for trypsin digestion and LC-MS/MS.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Hemolysis Assay for Cytotoxicity Screening Objective: To rapidly assess the membrane-lytic potential of nanoparticles, linked to surface charge and hydrophobicity. Materials: Fresh human or animal red blood cells (RBCs), PBS, Triton X-100 (1% v/v, positive control), nanoparticles. Steps:

- Wash RBCs 3x with PBS and prepare a 5% v/v suspension.

- Incubate 100 µL of RBC suspension with 100 µL of nanoparticle solutions (serial dilutions in PBS) for 1h at 37°C.

- Centrifuge at 500 x g for 5 min.

- Measure absorbance of supernatant at 540 nm (peak for hemoglobin).

- Calculate % hemolysis: [(Abssample - AbsPBS) / (AbsTritonX100 - AbsPBS)] * 100. >5% hemolysis indicates significant membrane disruption.

Diagrams

Title: Biological Fate Dictated by Nanoparticle Size

Title: Nanoparticle-Induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Nanotoxicity/Immunogenicity Research |

|---|---|

| Dynabeads (Various Sizes/Coats) | Model particles with controlled size and surface chemistry for comparative uptake and activation studies. |

| CellROX Green/Orange Reagent | Flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy probe for detecting nanoparticle-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS). |

| Cytochalasin D | Pharmacologic inhibitor of actin polymerization; used to confirm phagocytic uptake pathways. |

| Recombinant Human/Mouse Cytokine ELISA Kits (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) | Gold-standard for quantifying specific inflammatory cytokine release from immune cells. |

| PEG-SH (Thiol-Polyethylene Glycol) | Common reagent for "PEGylating" and shielding gold, iron oxide, or other metallic nanoparticles to reduce protein binding and immunogenicity. |

| Polystyrene Nanoparticles (Fluorescent, Carboxyl/Amine-modified) | Commercially available standards with uniform size for calibrating instruments and as controls in uptake experiments. |

| Pierce LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit | Colorimetric assay for quantifying membrane integrity damage, a key endpoint for cationic nanoparticle toxicity. |

| Albumin from Bovine Serum (BSA), Fraction V | Used as a model "corona" protein or as a blocking/passivating agent to reduce non-specific nanoparticle interactions. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting for Integrated Omics and Imaging in Nanotoxicology

Thesis Context: This support content is designed for researchers investigating the mechanistic basis of nanoparticle (NP)-induced cytotoxicity and immunogenic responses, utilizing integrated omics and high-resolution imaging to deconvolute complex biological interactions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: During a multi-omics workflow (transcriptomics & proteomics) on NP-treated macrophages, I find poor correlation between mRNA and protein expression levels for key inflammatory markers. What are potential causes and solutions?

A1: This is a common challenge. Causes and troubleshooting steps are summarized below:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Post-Transcriptional Regulation | Check miRNA/siRNA expression data from sequencing. | Integrate miRNA-seq or perform ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) to assess translation efficiency. |

| Protein Turnover/Degradation Rates | Review proteasome/autophagy pathway activity in proteomics data. | Use pulsed SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture) to measure protein half-lives. |

| Technical Discrepancy in Sample Timing | Verify harvest times are identical for both analyses. | Standardize: harvest all samples for omics at the exact same post-exposure time point. |

| NP Interference with Assay Kits | Run a spike-in control with known protein/mRNA concentration. | Include an extra purification step (e.g., column-based cleanup) post-lysis to remove NP residues. |

Q2: In live-cell imaging of mitochondrial depolarization (using JC-1 dye) following NP exposure, I observe inconsistent dye aggregation/ratio values. How can I resolve this?

A2: Inconsistencies often stem from NP-dye interactions or imaging protocol issues.

| Issue | Troubleshooting Step | Protocol Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| NP Adsorption of Dye | Image a dye-only control with NPs. | Pre-incubate NPs with serum-containing media to form a corona before adding dye-loaded cells. |

| Photobleaching/J-aggregate Instability | Check intensity loss over time in control wells. | Reduce illumination intensity/time, use a neutral density filter, and take rapid sequential images. |

| Variable NP Settling | Check focal plane for uneven cell layers. | Use a gentle, continuous agitation system during exposure or plate cells on a confocal dish with a #1.5 coverglass bottom. |

Q3: When integrating single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data with high-resolution immunofluorescence images for spatial context, how do I align the two datasets from the same sample?

A3: Use a computational anchor-based integration workflow.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Split your NP-treated cell population (e.g., primary immune cells).

- Portion A: Process for scRNA-seq using a standard 10x Genomics protocol.

- Portion B: Seed onto imaging chamber slides, fix, and stain with a panel of 5-10 antibodies for key markers (e.g., CD45, CD68, MHC-II, TNF-α).

- Imaging: Acquire high-resolution (60x) multi-channel images. Extract cell-specific expression values for the antibody panel (mean fluorescence intensity per cell).

- Computational Integration:

- Create a "pseudo-bulk" reference from the scRNA-seq data for the antibody-target genes.

- Use tools like Seurat's

FindTransferAnchorsor Tangram to map the scRNA-seq data onto the spatial positions of imaged cells based on the shared antibody/transcript features.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function/Application in NP Cytotoxicity Research |

|---|---|

| LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Invitrogen) | Distinguishes live (calcein-AM, green) from dead (ethidium homodimer-1, red) cells in real-time after NP exposure. |

| CellROX Deep Red Oxidative Stress Reagent | Fluorogenic probe for measuring reactive oxygen species (ROS) in live cells via high-content imaging or flow cytometry. |

| Olink Target 96 Inflammation Panel | Multiplex, antibody-based proteomics assay for 92 inflammatory proteins from small sample volumes; ideal for supernatant from NP-treated cells. |

| MitoTracker Deep Red FM | Cell-permeant dye that stains mitochondria in live cells; useful for tracking mitochondrial morphology and localization upon NP insult. |

| Nucleofector Technology (Lonza) | Enables high-efficiency transfection of hard-to-transfect primary immune cells (e.g., macrophages) for CRISPR or reporter gene assays. |

| Cytiva Biacore Series S CMS Chip | Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensor chip to characterize the kinetics of NP or protein corona binding to immune receptors (e.g., TLRs). |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) System (Malvern) | Measures NP size distribution and concentration in complex biological fluids (serum, BALF) prior to cell exposure. |

Table 1: Omics Signatures Associated with High-Cytotoxicity vs. Low-Cytotoxicity Nanoparticles (from Integrated Studies)

| Parameter | High-Cytotoxicity NPs (e.g., Cationic PS, certain metal oxides) | Low-Cytotoxicity NPs (e.g., PEGylated Liposomes, Silica-coated) |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomic Hallmark (Pathway Enrichment) | NLRP3 inflammasome activation, p53 pathway, ER stress/UPR | Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress response, xenobiotic metabolism |

| Proteomic Shift (Upregulated Proteins) | IL-1β, Caspase-1, HMGB1, Phospho-eIF2α | HO-1, SOD2, GSTP1, Catalase |

| Metabolomic Profile (LC-MS) | Depleted glutathione, increased succinate, lactate | Stable glutathione levels, normal TCA cycle intermediates |

| Characteristic Imaging Phenotype | Mitochondrial fragmentation, lysosomal membrane permeabilization, plasma membrane blebbing | Intact mitochondrial network, autophagosome formation, stable lysosomes |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM) for Visualizing NP Intracellular Fate

- Objective: To track the subcellular localization of immunogenic NPs and associate it with organelle damage.

- Steps:

- Labeling: Incubate NPs (e.g., 50 µg/mL) with a fluorescent tag (e.g., Cy5) for 1 hour. Purify via centrifugal filter.

- Cell Treatment: Seed primary dendritic cells on a MatTek grid-bottom dish. Expose to labeled NPs for the desired time (e.g., 4h).

- Live-Cell Imaging: Using a confocal microscope with an environmental chamber, locate a cell of interest and capture a Z-stack of the fluorescence signal.

- Fixation: Immediately fix cells in situ with 2.5% glutaraldehyde/2% PFA in 0.1M cacodylate buffer.

- EM Processing: Post-fix in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrate in ethanol, and embed in EPON resin directly on the dish.

- Sectioning & Imaging: Using the fluorescent map, trim the block to the region of interest. Cut 70-nm ultrathin sections. Acquire TEM images.

- Correlation: Use software (e.g., IMOD) to align the light and electron microscopy images.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

(Diagram Title: NP-Induced Cytotoxicity & Immunogenicity Cascade)

(Diagram Title: Integrated Omics-Imaging Experimental Workflow)

From Bench to Bedside: Standardized Methods for Assessing Nanoparticle Safety and Immune Activation

Essential In Vitro Assays for Cytotoxicity (MTT/XTT, LDH, Apoptosis/Necrosis Markers, ROS Detection)

Welcome to the Technical Support Center. This guide is designed to support researchers working within the critical field of nanoparticle cytotoxicity and immunogenic response, providing troubleshooting and FAQs for key in vitro assays.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

MTT/XTT Assay Section

Q1: My formazan crystals are not dissolving properly after adding the solubilization solution, leading to high background and inconsistent readings. What could be wrong? A: This is a common issue. Potential causes and solutions include:

- Cause 1: Insufficient incubation time with the solubilization solution (typically DMSO or SDS-based).

- Solution: Increase incubation time (e.g., extend to 4-6 hours) on an orbital shaker, protected from light.

- Cause 2: Evaporation of culture medium during the MTT incubation, causing crystal precipitation in dry areas.

- Solution: Ensure plates are sealed with parafilm during the MTT incubation step and humidity is maintained.

- Cause 3: Nanoparticle interference. Some nanoparticles can directly reduce MTT or adsorb the formazan product.

- Solution: Include critical controls: wells with nanoparticles but no cells, and wells with nanoparticles in complete medium. Centrifuge plates before measuring absorbance to pellet insoluble nanoparticles/interfering materials.

Q2: I observe unexpected stimulation of metabolic activity (increased signal) at low nanoparticle concentrations. Is this real or an artifact? A: While low-dose stimulation (hormesis) is possible, nanoparticle interference is more likely.

- Artifact Cause: Certain nanomaterials (e.g., carbon-based, some metal oxides) can catalyze the reduction of MTT/XTT tetrazolium salts independent of cellular enzymes.

- Troubleshooting: Perform the "nanoparticle-only" control as stated above. Consider switching to a different assay (e.g., LDH, ATP) for validation. For XTT, ensure the electron coupling reagent is fresh and properly mixed.

LDH Assay Section

Q3: The LDH release in my positive control (Triton X-100 treated) is lower than expected, indicating poor assay sensitivity. A: This suggests suboptimal cell lysis or reagent issues.

- Solution 1: Verify the concentration and incubation time of the lysis agent. For robust cell lines, increasing Triton X-100 to 1-2% or extending lysis time to 45-60 minutes may be necessary.

- Solution 2: Check reagent stability. The NAD+ substrate and dye mixture are often light and temperature sensitive. Prepare fresh or use a commercially available, validated kit.

- Protocol Reminder: After adding the lysis solution, visually confirm cell detachment under a microscope.

Q4: How do I differentiate between apoptotic and necrotic LDH release in nanoparticle-treated cells? A: Standard LDH measures total plasma membrane damage. To differentiate:

- Experimental Setup: At your assay timepoint, collect two sets of supernatant: 1) Spontaneous LDH (from wells with untreated/media-changed cells). 2) Total LDH (from wells where you add lysis buffer at the end to release all remaining LDH).

- Calculation: Necrotic Release (%) = (Spontaneous LDH from treated wells / Total LDH from treated wells) x 100. Low spontaneous release with high total LDH indicates early apoptosis (intact membrane). High spontaneous release indicates necrosis or late apoptosis.

Apoptosis/Necrosis Markers Section

Q5: My flow cytometry results for Annexin V/PI are showing a high percentage of cells in both early (Annexin V+/PI-) and late (Annexin V+/PI+) apoptosis, but the negative control also shows a background signal. A: Background can arise from several sources.

- Cause 1: Mechanical stress during cell harvesting (especially if cells are adherent and require trypsinization).

- Solution: Use gentle detachment methods. For nanoparticle-treated cells, consider harvesting supernatant (containing detached apoptotic/necrotic cells) AND adherent cells separately, then combine for analysis.

- Cause 2: Calcium concentration is critical for Annexin V binding.

- Solution: Ensure the binding buffer contains the recommended 2.5 mM Ca2+. Use a commercial buffer for consistency.

- Cause 3: Nanoparticle auto-fluorescence or light scattering interference.

- Solution: Include nanoparticle-only samples to set appropriate gating and compensation. Use a wash step with PBS after staining to reduce background.

Q6: What are the key markers to confirm immunogenic cell death (ICD) induced by nanoparticles, beyond standard apoptosis assays? A: ICD involves the emission of "danger signals" or Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs).

- Key Surface Marker: Calreticulin (CRT) translocation to the plasma membrane (detectable by flow cytometry).

- Key Released Mediators: Extracellular ATP (measured by luciferase-based assays) and High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) release into supernatant (measured by ELISA).

- Workflow: Treat cells with nanoparticles, collect supernatant for ATP/HMGB1, and analyze adherent cells for surface CRT.

ROS Detection Section

Q7: My ROS probe (e.g., DCFH-DA) shows an instant spike upon adding nanoparticles, even in cell-free conditions. How do I interpret this? A: This indicates probe-nanoparticle interaction, not cellular ROS.

- Artifact Cause: Many nanomaterials (e.g., CeO2, Mn3O4) possess intrinsic catalase- or peroxidase-like activity that can oxidize the dye.

- Solution: Always run a cell-free control with nanoparticles + dye. Consider using multiple, chemically distinct ROS probes (e.g., DHE for superoxide) for confirmation. For intracellular validation, use pre-treatment with a ROS scavenger like N-acetylcysteine (NAC) to see if the signal is quenched.

Q8: How can I determine if ROS generation is a primary cause of cytotoxicity or a secondary consequence of cell death? A: Perform a time-course and inhibitor study.

- Protocol: Measure ROS generation at earlier time points (e.g., 30min, 1h, 3h, 6h) post-nanoparticle exposure, well before significant cell death occurs (as measured by LDH or Annexin V). In parallel, pre-treat cells with an antioxidant (e.g., 5mM NAC) for 1-2h before nanoparticle addition, then measure both ROS and subsequent cell death (e.g., at 24h). If NAC pre-treatment inhibits both early ROS and later cell death, it suggests a causal role.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Cytotoxicity Assays

| Assay | What it Measures | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Optimal Readout Time Post-NP Exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTT/XTT | Cellular metabolic activity (dehydrogenase enzymes) | High-throughput, inexpensive, well-established. | Susceptible to NP interference; measures viability, not direct death. | 24-72 hours |

| LDH Release | Plasma membrane integrity (cytosolic enzyme leak) | Direct measure of cytolysis/necrosis; easy protocol. | Cannot detect early apoptosis; serum can contain LDH. | 4-24 hours |

| Annexin V/PI | Phosphatidylserine exposure (Apoptosis) & membrane integrity (Necrosis) | Distinguishes apoptosis stages & necrosis. | Requires flow cytometry; sensitive to handling. | 6-48 hours (time-course) |

| ROS Detection | Reactive Oxygen Species (e.g., H2O2, superoxide) | Early event indicator; mechanistic insight. | High artifactual potential from NPs; probe specificity issues. | 0.5-6 hours |

Table 2: Common Artifacts & Controls for Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity Testing

| Interference Type | Affected Assay(s) | Recommended Control Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Activity | MTT/XTT, ROS probes | Cell-free control: NPs + assay reagents. |

| Adsorption | MTT/XTT (formazan), LDH, cytokines | Supernatant incubation control: Incubate released product (e.g., LDH) with NPs, then measure. |

| Light Scattering/Absorption | All colorimetric/fluorimetric assays | NP-only background control: NPs in medium + assay reagents. |

| Auto-fluorescence | Flow cytometry, fluorimetric assays | NP-only sample for flow gating/background subtraction. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: MTT Assay for Nanoparticle-Treated Cells (with NP controls)

- Seed cells in a 96-well plate and incubate for 24h.

- Treat cells with nanoparticle suspensions or controls (media, positive control like 100µM H2O2) for desired time.

- Prepare NP-Control Plate: In a separate plate, add NPs to cell-free medium.

- Add MTT: To both plates, add MTT reagent (0.5 mg/mL final concentration). Incubate 2-4h at 37°C.

- Solubilize: Carefully remove medium, add DMSO (or specified solubilizer). Shake gently for 15 min.

- Measure: Read absorbance at 570 nm, with a reference at 650 nm. Correct treated cell values with NP-control plate values.

Protocol 2: Annexin V-FITC/PI Staining for Flow Cytometry

- Harvest Cells: Collect supernatant (contains detached cells) and gently trypsinize adherent cells. Pool, wash twice with cold PBS.

- Stain: Resuspend ~1x10^5 cells in 100µL 1X Annexin V Binding Buffer. Add 5µL Annexin V-FITC and 5µL Propidium Iodide (PI). Incubate for 15 min at RT in the dark.

- Analyze: Add 400µL binding buffer and analyze within 1 hour on a flow cytometer. Use unstained, Annexin V-only, and PI-only controls for compensation.

Protocol 3: Intracellular ROS Detection using DCFH-DA

- Load Probe: After NP treatment, replace medium with serum-free medium containing 10-20µM DCFH-DA. Incubate 30 min at 37°C.

- Wash: Wash cells 2-3 times with PBS to remove extracellular dye.

- Measure: For fluorescence plate readers: Add fresh PBS and measure fluorescence (Ex/Em ~485/535 nm). For microscopy, image immediately. Include controls: Untreated cells (basal ROS), NPs + dye in cell-free wells, and a positive control (e.g., 100µM tert-Butyl hydroperoxide, 30 min).

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NP Cytotoxicity Testing

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Critical Notes for Nanoparticle Research |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrazolium Salts (MTT, XTT) | Indicator of cellular metabolic activity. | Use with interference controls. XTT requires an electron coupling reagent. |

| LDH Detection Kit | Quantifies lactate dehydrogenase release from cytosol. | Ideal for measuring necrotic damage. Ensure kit components are fresh. |

| Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Kit | Differentiates live, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells. | Calcium-dependent binding; handle cells gently to avoid false positives. |

| Cell-permeable ROS Probes (DCFH-DA, DHE) | Detect intracellular reactive oxygen species. | Highly prone to artifact; cell-free nanoparticle-probe controls are mandatory. |

| N-acetylcysteine (NAC) | Broad-spectrum antioxidant. | Used (5-10mM pre-treatment) to test causal role of ROS in NP toxicity. |

| Triton X-100 (1-2% in PBS) | Positive control for LDH assay (causes complete cell lysis). | Verify complete lysis under microscope for your cell type. |

| Calreticulin (CRT) Antibody | Detect surface CRT exposure for Immunogenic Cell Death (ICD). | Use non-permeabilized cells for flow cytometry to confirm surface localization. |

Diagrams

Title: NP Cytotoxicity & Assay Interference Pathways

Title: MTT Assay Workflow with NP Control

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: In our DC maturation assay using nanoparticle (NP)-treated monocyte-derived DCs, we are seeing high variability in CD86 and HLA-DR surface expression between donors. What could be the cause and how can we mitigate this? A: High donor-to-donor variability in DC maturation markers is a common challenge, often linked to the donor's immune status and monocyte isolation efficiency.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Standardize Monocyte Isolation: Use positive selection (CD14+ microbeads) instead of plastic adherence for higher purity and consistency.

- Include Reference Controls: In every experiment, include a well-characterized positive control (e.g., 100 ng/mL LPS + 20 ng/mL IFN-γ) and an inert negative control (e.g., PBS-treated). This normalizes donor responses.

- Increase Replicates: Use cells from at least 3 different donors in triplicate for statistical power.

- Check NP Sterility: Perform an endotoxin/LAL test on your NP stock. Contaminating endotoxin is a potent, variable DC activator.

Q2: Our cytokine release assay (Luminex/ELISA) from PBMCs exposed to NPs shows unexpectedly low or undetectable levels of key cytokines like IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β. What are potential reasons? A: Low cytokine detection can stem from assay sensitivity, cell health, or NP interference.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Cell Viability: Use a live/dead stain (e.g., propidium iodide) to ensure NP cytotoxicity isn't reducing the responding cell population. Frame data within your thesis's cytotoxicity findings.

- Optimize Incubation Time: Kinetic profiles differ. Sample supernatants at multiple time points (e.g., 6, 24, 48 hours).

- Check for Assay Interference: Some NPs can adsorb cytokines or interfere with detection antibodies. Perform a spike-and-recovery experiment by adding a known cytokine concentration to NP-treated supernatant.

- Increase Cell Concentration: Use 1-2 x 10^6 PBMCs/mL to ensure sufficient secretor cells.

Q3: During leukocyte activation profiling by flow cytometry, we observe high background fluorescence in channels detecting FITC and PE after NP treatment. How do we address this? A: This indicates NP autofluorescence or non-specific antibody binding, which confounds activation marker detection.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Include NP-Only Controls: Always stain cells treated with NPs without antibodies to establish autofluorescence levels. Use this to set compensation and gating thresholds.

- Titrate Antibodies: Perform antibody titration on NP-treated cells to find the optimal signal-to-noise ratio.

- Use a Viability Dye: Distinguish live cells, as dead cells exhibit high non-specific binding. Use a near-IR fixable viability dye to avoid spectral overlap.

- Implement a Blocking Step: Incubate cells with Fc receptor blocking reagent (human TruStain FcX) for 10 minutes prior to surface antibody staining.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized DC Maturation Assay Objective: To assess the impact of nanoparticles on dendritic cell maturation.

- Isolate CD14+ Monocytes from human PBMCs using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS).

- Differentiate into Immature DCs (iDCs): Culture 1x10^6 cells/mL in RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS, 100 ng/mL GM-CSF, and 50 ng/mL IL-4 for 6 days. Refresh cytokines on day 3.

- NP Exposure: On day 6, harvest iDCs and seed at 5x10^5 cells/mL. Treat with a range of NP concentrations (based on your cytotoxicity thesis data), positive control (LPS+IFN-γ), and negative control (vehicle). Incubate for 24h.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Harvest cells, wash, and stain with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD83, CD86, HLA-DR, and CD11c. Include a viability dye. Analyze on a flow cytometer. Gate on live, CD11c+ cells to calculate MFI and % positive for maturation markers.

Protocol 2: Multiplex Cytokine Release Assay from PBMCs Objective: To quantitatively profile a broad panel of cytokines released upon NP exposure.

- PBMC Preparation: Isfresh PBMCs from healthy donor blood via density gradient centrifugation.

- Stimulation: Seed PBMCs at 1x10^6 cells/well in a 96-well plate. Treat with NPs, positive control (e.g., 1 µg/mL PHA-L), and negative control. Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 hours.

- Supernatant Collection: Centrifuge plate at 300 x g for 5 min. Carefully collect supernatant into a fresh tube. Centrifuge again at 500 x g for 10 min to remove residual cells/debris. Store at -80°C.

- Luminex Assay: Thaw samples on ice. Use a commercially available human cytokine 25-plex panel (e.g., Invitrogen) following manufacturer instructions. Briefly, mix samples with antibody-coated magnetic beads, incubate, wash, add detection antibody, then streptavidin-PE. Analyze on a Luminex analyzer. Generate standard curves for each cytokine for quantification.

Data Summary Tables

Table 1: Expected DC Maturation Marker Expression (Mean Fluorescence Intensity Range)

| Stimulus | CD83 MFI | CD86 MFI | HLA-DR MFI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immature DCs | 200 - 500 | 1,000 - 3,000 | 10,000 - 30,000 |

| LPS + IFN-γ | 8,000 - 15,000 | 20,000 - 50,000 | 80,000 - 150,000 |

| "Low-Reactogenic" NP | 500 - 2,000 | 5,000 - 15,000 | 30,000 - 70,000 |

| "High-Reactogenic" NP | 5,000 - 12,000 | 15,000 - 40,000 | 60,000 - 120,000 |

Table 2: Typical Cytokine Release Ranges from PBMCs (pg/mL)

| Cytokine | Unstimulated | PHA-L Stimulated | Threshold for Positive Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 5 - 50 | 1,000 - 10,000 | > 100 |

| TNF-α | 10 - 100 | 2,000 - 8,000 | > 200 |

| IL-1β | < 20 | 500 - 4,000 | > 50 |

| IFN-γ | < 10 | 5,000 - 20,000 | > 100 |

| IL-10 | < 20 | 200 - 1,500 | > 50 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Ficoll-Paque Premium | Density gradient medium for high-viability PBMC isolation from whole blood. |

| CD14 MicroBeads, human | For positive selection of monocytes with high purity for consistent DC differentiation. |

| Recombinant GM-CSF & IL-4 | Essential cytokines to drive monocyte differentiation into immature dendritic cells. |

| LPS (Ultra-Pure, from E. coli) | Standard positive control for robust TLR4-mediated DC maturation and cytokine induction. |

| LIVE/DEAD Fixable Viability Dyes | Critical for excluding dead cells in flow cytometry, which bind antibodies non-specifically. |

| Human TruStain FcX (Fc Receptor Block) | Reduces background in flow cytometry by blocking non-specific antibody binding. |

| LEGENDplex Human Inflammation Panel | Pre-configured multiplex bead array for simultaneous, precise quantification of 13+ cytokines. |

| Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) | For parallel assessment of NP cytotoxicity (cell viability) via WST-8 reduction. |

Visualization: Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Diagram 1: NP Immune Recognition & Signaling Pathways

Diagram 2: Comprehensive Immunogenicity Profiling Workflow

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our nanoparticle formulation shows unexpected acute toxicity in mice at a dose deemed safe in vitro. What are the primary systemic factors to investigate? A1: Unexpected in vivo acute toxicity often stems from factors not captured in cell cultures. Prioritize investigating: 1) Complement Activation-Related Pseudoallergy (CARPA): A common hypersensitivity reaction to nanocarriers. Monitor for transient hypotension, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia immediately post-injection. 2) Liver/Kidney Sequestration: High accumulation can cause organ-specific toxicity. Check for elevated serum ALT, AST, and BUN/creatinine. 3) Nanoparticle Aggregation in Blood: Size aggregation can cause capillary blockade. Examine blood smears or use dynamic light scattering on blood samples post-administration. 4) Impurity Leaching: Metal ions or organic solvents from synthesis can cause systemic effects. Perform ICP-MS on blood samples.

Q2: During a chronic toxicity study (28-day repeat dose), we observe gradual weight loss and reduced activity in the treatment group. How should we differentiate between immunogenic response and general toxicity? A2: This requires a multi-parameter approach. Follow this diagnostic workflow:

- Clinical Pathology: Run CBC with differential (look for sustained neutrophilia/lymphopenia) and serum cytokine panels (IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ) at multiple time points.

- Histopathology with Specific Staining: Beyond H&E, perform immunohistochemistry on key organs (spleen, liver, injection site) for CD68+ (macrophage infiltration), CD3+ (T-cell infiltration), and signs of germinal center formation.

- Anti-Nanoparticle Antibody Assay: Collect serum pre-dose and at termination. Use an ELISA where plates are coated with your nanoparticle. Detect IgM/IgG to confirm an adaptive immune response.

- Control Comparison: Ensure you have a "vehicle control" group (receiving all excipients without the active nanoparticle) to rule out excipient-related chronic inflammation.

Q3: Biodistribution data from IVIS or radioactive labeling shows inconsistent organ accumulation between animals. What are the top technical sources of this variability? A3: High variability in biodistribution often originates from administration technique and nanoparticle preparation.

- Injection Technique: For intravenous (IV) tail vein injections, inconsistent rate, bolus leakage, or partial intra-arterial administration drastically alters first-pass distribution. Standardize injection volume, rate (use syringe pumps), and needle size. Always use warm cages for tail vein dilation.

- Nanoparticle Stability: Aggregation post-resuspension or in storage leads to non-uniform dosing. Always characterize hydrodynamic size and PDI via DLS immediately before animal dosing. Filter samples through a 0.22 µm filter if compatible.

- Animal Physiology: Fasting state, circadian rhythm, and age/sex can influence mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS) activity. Strictly control animal husbandry conditions and randomize adequately.

- Imaging Artifacts: For IVIS, ensure animals are shaved uniformly and positioned identically. Account for autofluorescence in organs like the gut.

Q4: We suspect a Type I (IgE-mediated) or Type IV (T-cell mediated) hypersensitivity reaction to our nano-formulation. What are the definitive rodent models and readouts? A4:

- For Type I Hypersensitivity (Anaphylaxis):

- Model: Passive Cutaneous Anaphylaxis (PCA) in rats or mice. Pre-sensitize with nanoparticle + adjuvant, then later challenge with nanoparticle IV along with Evans blue dye.

- Definitive Readout: Extravasation of Evans blue at the sensitization site, measured by dye extraction and spectrophotometry. Also measure serum mast cell protease (MMCP-1 in mice) immediately after challenge.

- For Type IV Hypersensitivity (Delayed-Type):

- Model: Local Lymph Node Assay (LLNA) or Guinea Pig Maximization Test (for stronger prediction).

- Definitive Readout (LLNA): Apply nanoparticle to ear dorsum for 3 consecutive days. On day 5, inject ³H-thymidine. Isolate auricular lymph nodes and measure proliferation via ³H-thymidine incorporation. A Stimulation Index >3 indicates sensitization potential.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Mortality During Acute Toxicity (LD50) Study.

- Step 1 (Immediate): If mortality occurs within minutes, suspect CARPA or acute embolism. Necropsy immediately, focusing on lungs for signs of edema and hemorrhage. Collect blood for complement factor analysis (C3a, SC5b-9).

- Step 2 (Dose Preparation): Re-audit dose calculation and preparation. Verify nanoparticle concentration (via absorbance, elemental analysis), sterility (perform rapid endotoxin test), and absence of large aggregates (use DLS/NTA).

- Step 3 (Administration): Review injection records. Consider step-wise dosing starting at << expected toxic dose to establish a response curve. Implement ECG/respiratory monitoring for next cohort.

Issue: Poor Signal-to-Noise in Quantitative Biodistribution via ICP-MS.

- Problem: Background elemental levels too high or nanoparticle signal too low.

- Solution Checklist:

- Digestion: Use trace metal-grade nitric acid and peroxides in a closed-vessel microwave digester for complete tissue digestion.

- Background Control: Analyze tissues from naive animals (no injection) to establish precise baseline element levels. Subtract this background.

- Washing: Perfuse animals thoroughly with saline-EDTA via cardiac puncture post-euthanasia to remove blood pool signal.

- Signal Enhancement: If using gold or other elemental tags, consider signal amplification techniques. Ensure your nanoparticle has a sufficiently high payload of the detectable element.

Issue: Failure to Elicit Immune Response in Adjuvant Studies for Immunogenicity Assessment.

- Problem: Nanoparticle intended as a vaccine carrier shows no antibody titer.

- Solution Flow:

- Validate Antigen Integrity: Confirm the antigen is properly conjugated/adsorbed and not degraded. Run an SDS-PAGE or HPLC.

- Optimize Adjuvant/Route: Switch from subcutaneous to intramuscular. Consider adding a known adjuvant (e.g., Alum, CpG) to your formulation in a prime-boost regimen.

- Timing: Ensure an appropriate boost schedule (typically 2-3 weeks post-prime). Collect serum 10-14 days post-boost for peak antibody titer.

- Readout Sensitivity: Use a more sensitive assay than standard ELISA (e.g., electrochemiluminescence). Ensure your coating strategy efficiently captures the nanoparticle-antigen complex.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Standard Parameters for Acute & Chronic Rodent Toxicity Studies of Nanomaterials

| Parameter | Acute Study (Single Dose) | Chronic Study (Repeated Dose, e.g., 28-day) | Key Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation Duration | 14 days | Daily, for study duration + recovery period | Clinical scoring sheets, video monitoring. |

| Clinical Signs | Twice daily for first 4 hrs, then daily. | At least once daily. | Detailed check for piloerection, respiration, secretions, motility. |

| Body Weight | Recorded daily. | Recorded 1-3 times per week. | Statistical analysis of trends. |

| Food/Water Consum. | Optional, but recommended. | Measured weekly. | Per-cage or individual metabolic caging. |

| Hematology | Terminal only (Day 14). | Interim (Day 14) and Terminal (Day 28+). | CBC, differential, coagulation panel. |

| Clinical Chemistry | Terminal only (Day 14). | Interim and Terminal. | Liver (ALT, AST, ALP), Kidney (BUN, Creatinine), Inflammation (CRP). |

| Gross Necropsy | All animals, at death or terminal. | All animals. | Standardized organ weight protocol (heart, liver, spleen, etc.). |

| Histopathology | Target organs from all dose groups. | Full tissue list from control and high-dose, target organs from all. | H&E staining; IHC if indicated (e.g., CD68, Caspase-3). |

Table 2: Common Biodistribution Measurement Techniques & Their Characteristics

| Technique | Detection Limit | Spatial Resolution | Quantitative? | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radioactive Labeling (γ-counter) | ~ng | Organ level | Excellent | Gold standard, highly quantitative, deep tissue. | Radiation safety, label detachment. |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | pg-ng | Organ level | Excellent | Ultra-sensitive, multi-element, absolute quantitation. | Destructive, no real-time data. |

| Fluorescence Imaging (IVIS) | ~µg | ~1-3 mm (2D) | Semi-quantitative | Real-time, longitudinal, easy. | Limited depth, autofluorescence, quenching. |

| X-ray Computed Tomography (CT) | mg (for heavy elements) | ~50-100 µm | Good for high-Z materials | Anatomical context, high resolution. | Low sensitivity for most nanomaterials. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Acute Systemic Toxicity Test (OECD Guideline 425 Adapted for Nanomaterials) Objective: To estimate the LD50 or identify signs of acute toxicity after a single intravenous bolus. Materials: Test nanoparticle suspension, vehicle control, sterile syringes (1 mL), 27G needles, rodent restrainer, warm cage or lamp, healthy mice/rats (6-12 weeks, n=5/group minimum). Procedure:

- Dose Preparation: Sonicate nanoparticle suspension (e.g., water bath, 5 min) and filter (0.22 µm) immediately before dosing. Confirm concentration.

- Animal Preparation: Place animals in a warm cage (∼30°C) for 5-10 minutes to dilate tail veins.

- Administration: Using a syringe pump, administer a single bolus IV via the lateral tail vein at a constant rate (e.g., 100 µL/10 sec for a 200 µL volume). Record exact time.

- Immediate Observation: Observe animals individually for the first 30 minutes, then at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 hours post-dose. Record clinical signs (lethargy, dyspnea, tremor, piloerection).

- Follow-up: Weigh animals daily for 14 days. Note any mortality or moribund state.

- Terminal Analysis: On day 14, euthanize survivors. Collect blood for hematology/serum chemistry. Perform gross necropsy and weigh key organs. Preserve organs in 10% NBF for histopathology. Key Adaptation for Nano: Include a group injected with a known complement activator (e.g., liposomal doxorubicin) as a positive control for hypersensitivity.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Biodistribution via Radioisotope Labeling Objective: To determine the percentage of injected dose (%ID) per gram of tissue over time. Materials: Nanoparticle labeled with a gamma-emitting radionuclide (e.g., ¹¹¹In, ⁹⁹mTc, ⁶⁴Cu), dose calibrator, gamma counter, perfusion pump, pre-weighed tissue vials. Procedure:

- Dose Calibration: Precisely measure the radioactivity (µCi) of the prepared dose in a dose calibrator. Prepare a standard dilution for subsequent counting efficiency.

- Administration: Inject a known volume/activity IV via tail vein (as in Protocol 1).

- Time Points: Euthanize animals (n=5/time point) at pre-determined times (e.g., 5 min, 1h, 4h, 24h, 7d).

- Perfusion: To clear blood-pool radioactivity, perform transcardial perfusion with 20-30 mL of heparinized saline (10 U/mL) at a steady rate.

- Tissue Collection: Dissect and weigh all organs of interest (blood sample, heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, brain, muscle, bone, tail at injection site).

- Gamma Counting: Place each tissue in a vial and count in a gamma counter alongside the dose standard and background. Correct for decay and isotope half-life.

- Calculation: %ID/g = (Tissue counts / Counting efficiency) / (Injected dose counts) / (Tissue weight in grams) * 100%. Critical Step: Validate label stability >95% in serum incubation studies prior to in vivo use.

Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application in Rodent Nano-Studies |

|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Positive control for acute inflammatory response and cytokine storm. Used to validate assay sensitivity in toxicity studies. |

| Poloxamer 407 or Tween 80 | Common surfactants used to stabilize nanoparticle suspensions for injection, preventing aggregation in biological fluids. |

| Evans Blue Dye | Used in vascular permeability assays, such as the Passive Cutaneous Anaphylaxis (PCA) test, to quantify extravasation due to hypersensitivity. |

| Heparinized Saline | Used for systemic perfusion prior to tissue collection in biodistribution studies to clear the blood-pool signal, improving organ-specific data. |

| Rodent Serum/Plasma | Used for in vitro stability studies (DLS in serum) and to pre-coat nanoparticles to study protein corona formation before in vivo experiments. |

| Alum (Aluminum Hydroxide) | A common vaccine adjuvant used as a positive control in studies investigating nanoparticle immunogenicity and adaptive immune response. |

| Commercial ELISA Kits (MMCP-1, Cytokines) | For quantifying specific biomarkers: Mouse Mast Cell Protease-1 (MMCP-1) for anaphylaxis; IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ for systemic inflammation. |

| ³H-thymidine or BrdU | Used in the Local Lymph Node Assay (LLNA) to measure T-cell proliferation as a definitive readout for Type IV hypersensitivity potential. |

| ICP-MS Multi-Element Standards | Certified reference materials for calibrating ICP-MS instruments, essential for accurate quantitative biodistribution of metal-based nanomaterials. |

| Tissue Digestion Tubes (MTE) | Microwave-assisted, closed-vessel tubes made of Teflon for complete, contamination-free digestion of tissue samples prior to elemental analysis. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity & Immunogenicity Experiments

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My negative control wells show significant cell death. What could be the cause? A: This indicates a fundamental contaminant or experimental condition error.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Solvent Cytotoxicity: Ensure the vehicle (e.g., DMSO, PBS) used to suspend nanoparticles is at a non-toxic concentration (e.g., DMSO <0.1% v/v for most cell lines). Run a vehicle-only control.

- Assay Interference: Nanoparticles can interfere with common assays (e.g., MTT, LDH). They may catalyze redox reactions or adsorb assay components. Solution: Include a nanoparticle-only control (no cells) in your assay plate to check for signal interference. Consider switching to an interference-resistant assay (e.g., resazurin-based for metabolic activity, or a luminescent ATP assay).

- Check Sterility: Use sterile-filtered (0.22 µm) nanoparticle suspensions and media. Bacterial or endotoxin contamination can cause immune activation and death.

Q2: How do I choose the right dosage metric (e.g., mass concentration, particle number, surface area) for in vitro studies? A: The optimal metric depends on the hypothesized mechanism of action. Inconsistent metrics are a major source of irreproducibility in nanotoxicology.

- Guidance: Follow the recommendations from recent consensus papers.

- Troubleshooting: If your dose-response is erratic, test multiple metrics. For surface-area-driven toxicity (common with reactive metal oxides), calculate and dose based on specific surface area (m²/mL). For particle-number-dependent effects (e.g., cellular uptake saturation), use concentration derived from particle size analysis (# particles/mL). Always report all three: mass concentration (µg/mL), surface area, and particle number.

Q3: My nanoparticles aggregate heavily in biological media, skewing dosing and uptake. How can I stabilize them? A: Aggregation alters effective dose, hydrodynamic size, and cellular interaction.

- Protocol for Dispersion:

- Sonication: Sonicate the stock nanoparticle suspension in a water bath or with a probe sonicator (e.g., 30% amplitude, 10 min on ice to prevent overheating) immediately before dosing.

- Serum Pre-coating: Pre-incubate nanoparticles with 10-50% FBS or human serum in media for 30 min at 37°C to form a stabilizing "protein corona."

- Characterization: Critical: Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) after dispersion in the complete cell culture medium to be used in the experiment. This is your relevant dosing size.

Q4: My chosen immortalized cell line shows no immunogenic response to nanoparticles reported to be inflammatory in vivo. What biological model should I use? A: Immortalized lines often have dampened immune pathways.

- Solution:

- Primary Cells: Use primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), monocyte-derived macrophages, or dendritic cells. Protocol: Isolate PBMCs via density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque). Differentiate monocytes with GM-CSF (M1-like) or M-CSF (M2-like).

- Co-culture Models: Establish a transwell co-culture of epithelial cells and macrophages to study crosstalk.

- Reporter Cell Lines: Use THP-1 monocytic cells with an NF-κB or IRF reporter gene to quantitatively measure pathway activation.

Q5: How do I differentiate between caspase-dependent apoptosis and pyroptosis (immunogenic cell death) in my assay? A: Both cause DNA fragmentation and positive Annexin V staining, but pyroptosis is gasdermin-mediated and highly inflammatory.

- Diagnostic Protocol:

- Inhibitor Assay: Pre-treat cells with Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase inhibitor, 20 µM) and VX-765 (caspase-1 inhibitor, 10 µM). If cell death is inhibited only by VX-765, it suggests pyroptosis.

- Western Blot Markers:

- Apoptosis: Cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP.

- Pyroptosis: Cleaved caspase-1, mature IL-1β, cleaved gasdermin D (GSDMD-N terminal).

- Morphology: Image cells using high-content imaging. Pyroptotic cells exhibit large balloon-like protrusions (pyroptotic bodies), distinct from apoptotic blebbing.

Table 1: Common Dosage Metrics for Spherical Nanoparticles

| Metric | Calculation Formula | When to Use | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Concentration | Weighed mass / Volume (µg/mL) | Standard dosing, pharmaco-kinetic scaling | Ignores size and surface properties. |

| Particle Number | (Mass / (Density * Particle Volume)) / Volume (#/mL) | Uptake saturation studies, single-particle effects | Requires precise core size and monodispersity. |

| Total Surface Area | (Particle Surface Area) * (Particle Number) (m²/mL) | Surface-reactivity-driven toxicity (ROS, dissolution) | Requires accurate size and assumes spherical geometry. |

| Molar Concentration | (Mass / Molar Mass) / Volume (nmol/mL) | For molecularly defined nanoparticles (e.g., drug conjugates). | Not applicable for polydisperse inorganic materials. |

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of Biological Models for Immunogenicity

| Model System | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Best For Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immortalized Cell Line (e.g., THP-1) | Reproducible, easy, scalable, amenable to genetic modification. | Often have altered TLR/cytokine pathways; may not reflect primary cell physiology. | High-throughput toxicity ranking. |

| Primary Human PBMCs/Macrophages | Physiologically relevant, donor variability reflects human population. | Donor variability, finite lifespan, more expensive, requires ethical approval. | Mechanistic immunogenic response. |

| Murine Models (in vivo) | Full systemic response, ADME, organ-level pathology. | Species-specific immune differences, high cost, complex ethics. | Final pre-clinical validation. |

| Organ-on-a-Chip (Co-culture) | Captures tissue-tissue interfaces and fluid flow. | Technically complex, low-throughput, nascent validation. | Investigating nanoparticle translocation and secondary effects. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Nanoparticles Objective: To determine if nanoparticles activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to caspase-1 activation and IL-1β release. Materials: THP-1 cells (or primary human macrophages), PMA, LPS, ATP, nanoparticle suspension, IL-1β ELISA kit, caspase-1 activity assay kit, cell culture reagents. Procedure:

- Differentiation: Seed THP-1 cells at 2x10⁵ cells/well in a 24-well plate with 100 nM PMA for 48h. Rest in fresh media for 24h.

- Priming (Signal 1): Stimulate cells with ultrapure LPS (100 ng/mL) for 3h to induce pro-IL-1β transcription via NF-κB.

- Nanoparticle Challenge (Signal 2): Replace media with nanoparticle suspension in serum-free media (pre-dispersed). Incubate for 6h. Positive Control: Add ATP (5 mM) for the final 30 min.

- Analysis:

- Extracellular IL-1β: Collect supernatant, centrifuge (500xg, 5 min) to remove debris. Measure IL-1β via ELISA.

- Caspase-1 Activity: Lyse cells, measure activity using a fluorescent substrate (e.g., YVAD-AFC) per kit instructions.

- Cell Viability: Run a parallel plate with identical treatments and assay via ATP-based luminescence.

Protocol 2: Characterizing Nanoparticle-Hydrodynamic Size in Biological Media Objective: To measure the effective hydrodynamic diameter and stability of nanoparticles under experimental conditions. Materials: Nanoparticle stock, complete cell culture media (with serum), DLS instrument, 0.22 µm syringe filter, sonicator. Procedure:

- Preparation: Sonicate nanoparticle stock (as per Q3 protocol). Dilute to the highest test concentration (e.g., 100 µg/mL) in complete media. Do not filter after adding nanoparticles.

- Incubation: Incubate the suspension at 37°C for 0h, 1h, and 24h to mimic exposure times.

- Measurement: For each time point, transfer suspension to a clean, disposable DLS cuvette. Run DLS measurement at 37°C.

- Data Acquisition: Record the Z-average hydrodynamic diameter, polydispersity index (PDI), and intensity size distribution. A PDI >0.3 indicates a polydisperse/aggregated sample.

- Interpretation: Report the size at the time of dosing (0h in media). The 24h measurement indicates stability over the experiment's duration.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity Experiment Workflow

Diagram Title: Key Immunogenic vs. Apoptotic Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrapure LPS | Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) agonist; provides precise "Signal 1" for inflammasome priming studies. | InvivoGen (tlrl-3pelps) |

| ATP (disodium salt) | NLRP3 inflammasome activator; used as a positive control for "Signal 2" in macrophage assays. | Sigma Aldrich (A6419) |

| Z-VAD-FMK | Broad-spectrum, cell-permeable caspase inhibitor. Used to distinguish caspase-dependent from -independent cell death. | Cayman Chemical (14463) |

| VX-765 (Belnacasan) | Specific caspase-1 inhibitor. Critical tool to confirm inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis. | Selleckchem (S2228) |

| Poly(I:C) HMW | TLR3 agonist; positive control for testing nanoparticle-induced antiviral/interferon responses. | InvivoGen (tlrl-pic) |

| Recombinant Human M-CSF | For differentiating human monocytes into M2-like macrophages in vitro. | PeproTech (300-25) |

| Recombinant Human GM-CSF | For differentiating human monocytes into M1-like macrophages or dendritic cells. | PeproTech (300-03) |

| Dihydroethidium (DHE) | Cell-permeable fluorescent probe for detecting intracellular superoxide production (ROS). | Thermo Fisher (D11347) |

| Annexin V-FITC / PI Kit | Standard flow cytometry kit to discriminate apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-) and necrotic/late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+) cells. | BioLegend (640914) |

| 0.22 µm PES Syringe Filter | For sterile filtration of nanoparticle suspensions and media. Essential for preventing microbial contamination. | Millex-GP (SLGP033RS) |

Engineering for Safety: Proactive Strategies to Mitigate Cytotoxicity and Unwanted Immune Responses

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQs & Troubleshooting for PEGylation

Q1: After PEGylation, my nanoparticles show increased aggregation instead of improved stability. What could be the cause? A: This is often due to insufficient surface coverage or incorrect PEG chain density. Below a critical grafting density, PEG chains cannot form the necessary "mushroom" or "brush" conformation to provide steric stabilization, leading to bridging flocculation.

- Solution: Increase the molar ratio of PEG reagent to nanoparticle surface functional groups. Optimize reaction time and pH. Purify post-reaction to remove unreacted PEG that might cause depletion aggregation. Characterize final product with DLS and zeta potential.

Q2: I observe a significant drop in nanoparticle targeting ligand activity post-PEGylation. How can I mitigate this? A: This is a classic "shielding" issue. Nonspecific conjugation chemistry can modify the targeting ligand.