Non-Viral Nanoparticle Vectors for Gene Therapy: Current Advances, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of non-viral nanoparticle vectors for gene therapy, a field gaining significant momentum as a safer and more scalable alternative to viral vectors.

Non-Viral Nanoparticle Vectors for Gene Therapy: Current Advances, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of non-viral nanoparticle vectors for gene therapy, a field gaining significant momentum as a safer and more scalable alternative to viral vectors. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of lipid-based, polymer-based, and inorganic nanoparticles. The scope extends to methodological advances in delivering complex cargos like CRISPR/Cas9, troubleshooting of key challenges such as transfection efficiency and tissue-specific targeting, and a critical validation against established viral platforms. By synthesizing the latest research and clinical progress, this review serves as a strategic resource for navigating the development and application of non-viral gene delivery technologies.

The Rise of Non-Viral Vectors: Overcoming the Limitations of Viral Gene Delivery

Viral vectors, including adeno-associated virus (AAV), lentivirus, and adenovirus, are foundational tools in modern gene therapy and biological research, enabling efficient gene delivery both in vivo and in vitro [1]. Their ability to provide high transduction efficiency and long-term transgene expression has supported the development of approved treatments for conditions such as spinal muscular atrophy, inherited retinal dystrophy, and β-thalassemia [1]. However, their clinical application is constrained by significant challenges related to manufacturing scalability, immunogenicity, and insertional mutagenesis risks [2] [3]. These limitations underscore the clinical imperative to develop robust solutions that enhance the safety, efficiency, and scalability of viral vector technologies. This application note details these challenges and presents optimized protocols to address them, providing researchers with actionable methods to improve viral vector performance in critical experiments.

Current Challenges in Viral Vector Applications

The clinical and research use of viral vectors faces several persistent hurdles that impact the efficacy, safety, and practicality of gene delivery systems.

Manufacturing and Characterization Bottlenecks: The transition of gene therapies from clinical development to commercial licensure demands a substantial increase in viral vector manufacturing capacity—estimated at 1–2 orders of magnitude for many promising disease indications [2]. This scaling challenge is compounded by the need for rigorous characterization of critical quality attributes. Current analytical techniques for assessing attributes such as empty/full capsid ratios, titer, and post-translational modifications often suffer from low throughput, large sample requirements, and poorly understood measurement variability [4].

Safety and Immunogenicity Concerns: Retroviral and lentiviral vectors pose risks of insertional mutagenesis, where integration into the host genome can disrupt or dysregulate genes, potentially leading to oncogenic transformation [3]. Although improved self-inactivating (SIN) designs have reduced this risk, monitoring remains crucial [2] [3]. Immune responses also present barriers; for instance, AAV therapies can trigger reactions that limit transgene expression or necessitate immunosuppression [1].

Technical Limitations in Complex Systems: Efficient gene delivery remains challenging in physiologically relevant 3D models such as organoids. Their complex architecture presents significant barriers to uniform transduction, limiting their utility in assessing vector performance and dose-response relationships [5] [6].

Table 1: Key Challenges and Current Limitations in Viral Vector Applications

| Challenge Category | Specific Limitation | Impact on Research/Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing & Scalability | Limited production capacity for commercial-scale supply [2] | Restricts patient access and increases costs |

| Product Characterization | Lack of high-throughput, precise analytical methods [4] | Hampers quality control and lot consistency |

| Delivery Efficiency | Low transduction efficiency in 3D organoid systems [5] | Reduces predictive value in preclinical models |

| Safety & Monitoring | Risk of insertional mutagenesis with integrating vectors [3] | Requires long-term patient monitoring (up to 15 years) |

| Immune Response | Pre-existing or therapy-induced immunity to viral capsids [1] | Limits transduction efficiency and re-dosing potential |

Quantitative Analysis of Viral Vector Performance

Recent meta-analytic data highlights the variable protective efficacy of different viral vector platforms. A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis of vaccine strategies for foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV)—a model for viral vector research—demonstrated clear efficacy differences between platforms [7]. Subgroup analysis revealed that VLP and viral vector vaccines offered higher protection rates compared to other platforms, though wide confidence intervals indicate significant variability across studies [7]. This heterogeneity underscores the influence of vector design and production methods on clinical outcomes.

Table 2: Meta-Analysis of Vaccine Platform Efficacy (2020-2025) [7]

| Vaccine Platform | Risk Ratio (RR) | 95% Confidence Interval | Comparative Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Vector Vaccines | 1.90 | 0.08 – 46.65 | Higher protection, but high variability |

| Virus-Like Particle (VLP) Vaccines | 1.66 | 0.97 – 2.86 | Higher protection |

| Peptide-Based Vaccines | 1.09 | 0.75 – 1.57 | Moderate efficacy |

| Dendritic Cell-Based Vaccines | Not specified | Not specified | Limited benefit |

Beyond efficacy, optimizing transduction protocols can yield significant quantitative improvements. Research in 2025 demonstrated that a sequential treatment with polybrene (PB) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) enhanced AAV transduction efficiency in 3D organoid models by approximately 1.3- to 2-fold compared to single-agent treatments, and 1.7- to 2.5-fold compared to virus alone [5] [6]. This enhancement, achieved while maintaining cell viability above 80-90%, provides a clear methodology for overcoming barriers in complex 3D systems.

Enhanced Protocol for AAV Transduction in 3D Organoids

This optimized protocol leverages the synergistic effect of polybrene (PB), which facilitates viral entry by reducing electrostatic repulsion, and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), which modulates endosomal processing and TLR9-mediated innate immune responses [5] [6]. The sequential administration targets distinct stages of the viral transduction pathway, significantly improving efficiency in structurally complex systems.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced AAV Transduction

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Polybrene (PB) | Cationic polymer that enhances viral entry by neutralizing charge repulsion [5] | 8-10 μg/mL |

| Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) | Modulates endosomal processing and inhibits TLR9-mediated immune responses [5] | 15-20 μM |

| AAV Vectors (e.g., mCherry) | Gene delivery vehicle; validate titer and purity (empty/full capsid ratio) prior to use [4] | MOI 2×10^4 |

| Liver/Retinal Organoids | 3D model system; culture using established protocols [5] | N/A |

| Cell Viability Assay (CCK-8) | Assess cytotoxicity of treatment conditions [6] | N/A |

| TUNEL Assay Kit | Confirm preserved cellular integrity post-treatment [5] | N/A |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Preparation and Pre-treatment:

- Culture liver or retinal organoids using established protocols and validate at defined maturation stages [5].

- Prepare a working solution of PB at 8 μg/mL for liver organoids or 10 μg/mL for retinal organoids in the appropriate culture medium.

- Pretreat organoids with the PB solution for 4 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ [6].

Viral Transduction:

- Dilute the AAV vector (e.g., mCherry reporter) in fresh culture medium to a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 × 10⁴.

- Remove the PB-containing medium from the organoids.

- Add the virus-containing medium to the organoids and incubate for the duration specified for your specific AAV serotype and organoid model.

Post-treatment with HCQ:

- Prepare a working solution of HCQ at 20 μM for liver organoids or 15 μM for retinal organoids in culture medium.

- Following viral transduction, replace the virus-containing medium with the HCQ solution.

- Incubate liver organoids with HCQ for 36 hours and retinal organoids for 48 hours [5].

Analysis and Validation:

- After the HCQ post-treatment, replace with standard culture medium.

- Analyze transduction efficiency via confocal microscopy (e.g., mCherry fluorescence) on day 10 (liver) or day 15 (retinal) post-transduction.

- Quantify the mCherry-positive area or mean fluorescence intensity using image analysis software.

- Confirm minimal cytotoxicity and preserved cellular integrity using a TUNEL assay and cell viability assay (CCK-8), expecting TUNEL-positive cells to remain low (1.1–3.9%) with no significant differences from controls [5] [6].

Diagram 1: AAV Transduction Enhancement Workflow.

Expected Results and Quality Control

Implementation of this sequential protocol should yield a 1.3- to 2-fold increase in transduction efficiency compared to single-agent treatments, and a 1.7- to 2.5-fold increase compared to virus-only controls in both liver and retinal organoid models [5]. Bright-field imaging should confirm no adverse changes in organoid morphology or density. Flow cytometry and quantitative image analysis will validate the significant increase in both the proportion of transduced cells and the intensity of transgene expression (e.g., *p < 0.0001 and *p < 0.01 compared to virus-only groups) [6]. Crucially, cell viability should remain ≥80%, and TUNEL assays should show minimal apoptosis (1.1–3.9%), with no statistically significant differences from untreated controls [5].

Advanced Monitoring and Safety Assessment Protocol

For integrating vectors like lentivirus and gamma-retrovirus, monitoring insertion sites is critical for assessing long-term safety. The MELISSA (ModELing IS for Safety Analysis) framework provides a statistical approach for analyzing integration site (IS) data to quantify insertional mutagenesis risk [3].

Materials and Reagents

- Integration Site (IS) Data: Provided in BED file format, containing clone size estimates (read counts, UMIs, or shear site data) [3].

- Design Matrix: A file containing sample-specific covariates (e.g., condition, replicate, cell type, time post-therapy).

- Genome Annotation File: Standard file (e.g., GTF) for the reference genome.

- MELISSA R Package: The core statistical tool for analysis [3].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Input and Preparation:

- Compile IS tables from sequencing data in the required BED format.

- Create a design matrix specifying the experimental conditions and time points for all samples.

Statistical Modeling with MELISSA:

- Perform gene targeting rate analysis using logistic regression to identify genomic regions preferentially targeted by integration events. This model tests whether the observed IS frequency in a given gene deviates significantly from the genome-wide average.

- Perform clone fitness analysis to evaluate whether integration within a specific gene influences clonal expansion over time. This model tests if clones with IS in a given gene show growth rates different from the global baseline.

Downstream Analysis and Interpretation:

- Generate descriptive statistics and clonality indexes.

- Perform gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on results to identify biological pathways potentially affected by insertional mutagenesis.

- Use the model outputs—Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) statistics and regression coefficients—to identify genes with significant targeting or growth effects.

Diagram 2: Integration Site Analysis Workflow.

Expected Results and Quality Control

Application of MELISSA to preclinical or clinical IS data should successfully identify both known and novel genes associated with altered clonal fitness upon vector integration [3]. The framework is sensitive enough to detect early signs of clonal expansion, even in datasets without overtly concerning clonal abundances (e.g., with dominant clones representing only 1-9.5% of the population) [3]. Performance metrics from simulation studies, including Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and detection rates, should be evaluated to ensure statistical power given the sample size and effect size of the experiment.

The clinical translation of viral vector-based therapies necessitates overcoming significant hurdles in manufacturing, safety, and efficient gene delivery to complex physiological models. The protocols detailed herein—a combinatorial chemical treatment to enhance AAV transduction in 3D organoids and a robust statistical framework for assessing insertional mutagenesis risk—provide researchers with actionable strategies to address these imperatives. By adopting these optimized methods, scientists can improve the efficiency and predictive power of preclinical studies, contribute to the development of safer vector designs, and ultimately accelerate the advancement of reliable and accessible gene therapies.

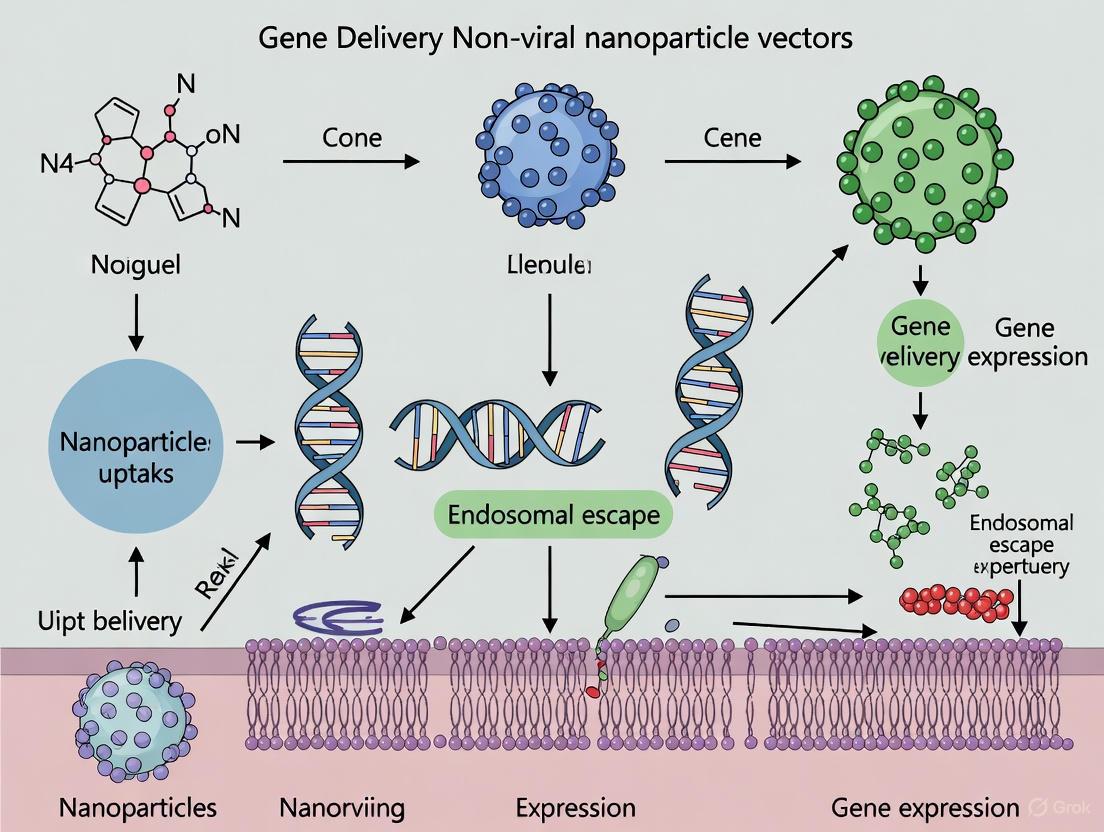

Gene therapy holds immense potential for treating genetic disorders, malignancies, and infectious diseases through the targeted introduction, silencing, or precise editing of therapeutic genes [8]. The clinical success of these advanced therapies is fundamentally constrained by the delivery vehicles, or vectors, used to transport genetic cargo into target cells. While viral vectors have historically dominated therapeutic applications due to their high transduction efficiency, they present significant challenges including robust immunogenicity, insertional mutagenesis risks, and limited cargo capacity [8] [1]. Non-viral nanoparticle vectors have consequently emerged as promising alternatives, offering superior safety profiles, manufacturing scalability, and expanded structural and functional reconfigurability to accommodate various cargo sizes [8].

The development of non-viral gene delivery systems represents a paradigm shift in therapeutic gene transfer, particularly with the advent of CRISPR-based gene editing technologies that require precise, transient delivery of editing components [9]. Nanoparticles, defined as particles with dimensions approximately 10⁻⁹ meters, exhibit distinctive behaviors due to their high surface area-to-mass ratios, enabling enhanced colloidal stability, novel electrical properties, and customizable surface characteristics [9]. These physicochemical properties make nanoparticles particularly suitable for overcoming the biological barriers to gene delivery, including nuclease-mediated degradation, cellular uptake limitations, and intracellular trafficking obstacles [10] [9].

This application note provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in gene therapy. We present structured quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and visualization tools to facilitate the implementation of non-viral nanoparticle platforms in research and therapeutic development, with particular emphasis on their core advantages in safety, scalability, and cargo capacity.

Quantitative Advantage Analysis

The comparative advantages of non-viral nanoparticle systems across safety, scalability, and cargo capacity parameters can be quantitatively assessed against viral vector systems. The data presented in the following tables provide a structured framework for objective evaluation during vector selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Vector Systems Based on Core Advantages

| Evaluation Parameter | Viral Vector Systems | Non-Viral Nanoparticle Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Safety Profile | • Immunogenicity: Moderate to High (e.g., Adenovirus: High; AAV: Low-Moderate) [1] [10]• Genomic Integration: Risk with Lentivirus/Retrovirus, leading to potential insertional mutagenesis [1] [10]• Pre-existing Immunity: Common for AAV and Adenovirus, may limit efficacy [1] | • Immunogenicity: Generally Low [8] [11]• Genomic Integration: Typically non-integrating, significantly reducing mutagenesis risk [8]• Toxicity Concerns: Primarily related to carrier material (e.g., cationic lipid/polymer toxicity) [9] |

| Scalability & Manufacturing | • Production Complexity: High; requires cell culture, purification from viral components [12]• Process Duration: Potentially months-long process with heterogeneous product yields [12]• Cost: High cost of goods (COGs) [1] | • Production Complexity: Low to Moderate; often uses scalable chemical synthesis [8]• Process Scalability: Highly scalable and reproducible manufacturing [8] [13]• Cost: Lower COGs compared to viral vectors [8] |

| Cargo Capacity | • Strict Limitations: AAV: ~4.7 kb [1] [11]; Lentivirus: ~8 kb [10]• Large Gene Challenge: Incompatible with large genetic elements without complex splitting strategies [1] | • Flexible & Large Capacity: Can be engineered to accommodate large DNA, mRNA, or RNP complexes (e.g., >10 kb) [8] [9]• Co-delivery Capability: Can deliver multiple therapeutic agents (e.g., Cas9 protein + gRNA + donor DNA) simultaneously [9] |

| Therapeutic Examples | • AAV: Luxturna, Zolgensma [1]• Lentivirus: CAR-T therapies (Kymriah, Zynteglo) [1] | • LNP: Patisiran (Onpattro) [1]• GalNAc-siRNA: Givosiran (Givlaari), Lumasiran (Oxlumo) [1] |

Table 2: Cargo Capacity and Characteristics of Non-Viral Nanoparticle Systems

| Cargo Type | Typical Size Range | Key Advantages | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | 3 - 20 kbp | Stable, long-term production of template for gene addition [10] | Gene replacement, long-term transgene expression |

| mRNA | 1 - 5 kb | Transient expression, no risk of genomic integration, rapid protein production [8] [11] | Vaccines, transient gene expression, CRISPR-Cas9 editing |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | ~160 kDa (Cas9) + gRNA | Immediate activity, highest precision, reduced off-target effects, shortest cellular residence [11] | CRISPR-based gene editing (knockout, knock-in) |

| Small RNA (siRNA, miRNA) | 19 - 25 bp (duplex) | Efficient gene silencing, well-established delivery chemistries (e.g., GalNAc) [1] | Gene silencing, target validation |

Table 3: Market and Clinical Adoption Trends (2024-2035 Projections)

| Metric | Viral Gene Delivery | Non-Viral Gene Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Market Share (2025) | ~66% [13] | ~34% (Including other non-viral) [13] |

| Projected CAGR (2025-2035) | 7.7% [13] | 5.8% (Segment including chemical/physical methods) [13] |

| Key Growth Driver | High efficiency in established therapies (e.g., CAR-T, monogenic diseases) [13] | Demand for safer, scalable platforms for CRISPR, mRNA vaccines, and personalized medicine [8] [13] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Formulation of Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) for mRNA Encapsulation

This protocol describes a standardized method for preparing LNPs using microfluidic mixing, suitable for encapsulating mRNA cargo for in vitro and in vivo delivery applications [11] [9].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Ionizable Cationic Lipid: e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA or SM-102; forms the core structure and enables endosomal escape.

- Helper Phospholipid: e.g., DSPC; enhances bilayer stability and fusogenicity.

- Cholesterol: Modulates membrane fluidity and stability.

- PEGylated Lipid: e.g., DMG-PEG2000; reduces particle aggregation and opsonization, improves stability.

- mRNA Cargo: Purified in vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA in citrate buffer (pH 4.0).

- Ethanol (absolute)

- Sodium Acetate Buffer (25 mM, pH 4.0)

- 1x Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

Procedure:

- Lipid Stock Preparation: Prepare the lipid mixture in ethanol at a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5 (Ionizable Lipid:DSPC:Cholesterol:PEG-Lipid) with a total lipid concentration of 12.5 mM. Warm slightly if needed to ensure complete dissolution.

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Dilute the mRNA cargo in 25 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0) to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL.

- Microfluidic Mixing:

- Use a commercial microfluidic mixer (e.g., NanoAssemblr) or a custom-made setup.

- Set the flow rate ratio (Aqueous:Ethanol) to 3:1.

- Simultaneously pump the aqueous mRNA solution and the ethanolic lipid solution into the mixing chamber at a combined total flow rate of 12 mL/min.

- Collect the resulting LNP suspension in a sterile vial.

- Buffer Exchange and Dialysis:

- Immediately dilute the formed LNPs with an equal volume of 1x PBS (pH 7.4).

- Transfer the solution to a dialysis cassette (e.g., 20 kDa MWCO) and dialyze against a >100x volume of 1x PBS for 4-6 hours at 4°C, with one buffer change.

- Characterization:

- Size and PDI: Measure by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). Target size: 70-100 nm; PDI: <0.2.

- Zeta Potential: Measure by Laser Doppler Velocimetry. Expected value: Slightly negative to neutral in PBS.

- Encapsulation Efficiency: Quantify using a Ribogreen assay. Compare fluorescence with and without a detergent (Triton X-100) to distinguish encapsulated vs. free mRNA. Target: >90%.

Protocol: Preparation of CRISPR Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes

This protocol details the formation of Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, a preferred cargo for precise genome editing due to rapid activity and minimal off-target effects [11].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Recombinant Cas9 Nuclease: High-purity, endotoxin-free, resuspended in storage buffer.

- Target-specific sgRNA: Chemically synthesized or in vitro transcribed, HPLC-purified.

- Nuclease-Free Duplex Buffer: (e.g., 30 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM Potassium Acetate).

- Nuclease-Free Water.

Procedure:

- sgRNA Preparation: Centrifuge the sgRNA tube briefly and resuspend in nuclease-free duplex buffer to a stock concentration of 160 µM. Store on ice.

- Complex Formation:

- Prepare the RNP complex in a nuclease-free microcentrifuge tube.

- For a 10 µL reaction, use a 1:1.2 molar ratio of Cas9 to sgRNA. A typical setup is:

- Cas9 (40 µM stock): 5 µL (200 pmol)

- sgRNA (160 µM stock): 1.5 µL (240 pmol)

- Nuclease-Free Duplex Buffer: 3.5 µL

- Gently pipette to mix. Do not vortex.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at room temperature (25°C) for 10-20 minutes to allow for complete RNP complex formation.

- Quality Control (Optional):

- Analyze complex formation using a native agarose gel (1-2%) or a gel shift assay. The RNP complex should show a mobility shift compared to free Cas9 protein.

- Immediate Use: The formed RNP complexes should be used immediately for transfection or can be stored on ice for a short period (<1 hour) before encapsulation into nanoparticles.

Protocol: Characterization of Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity and Immunogenicity

This protocol outlines standardized in vitro assays to evaluate the safety profile of formulated nanoparticles, a critical step in preclinical development [12] [9].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cell Line: Relevant human cell line (e.g., HEK293, HepG2, primary fibroblasts).

- Cell Culture Media: Appropriate complete media for the selected cell line.

- Test Nanoparticles: Formulated nanoparticles in PBS, sterile-filtered.

- MTT Reagent: (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) at 5 mg/mL in PBS.

- Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO)

- ELISA Kit for Human TNF-α or IL-6

- Flow Cytometry Staining Buffer (PBS + 1% BSA)

- Antibodies: Anti-human CD80, CD86, and MHC Class II, with appropriate isotype controls.

Procedure: Part A: Cell Viability Assay (MTT)

- Seed cells in a 96-well plate at a density of 1x10⁴ cells/well and incubate for 24 hours.

- Treat cells with a serial dilution of nanoparticles (e.g., 0, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/mL total lipid) in triplicate. Include a vehicle control (PBS) and a positive control for death (e.g., 1% Triton X-100).

- Incubate for 24-48 hours.

- Add 20 µL of MTT reagent to each well and incubate for 3-4 hours at 37°C.

- Carefully remove the media and solubilize the formed formazan crystals with 150 µL of DMSO.

- Measure the absorbance at 570 nm using a plate reader. Calculate cell viability as a percentage of the vehicle control.

Part B: Innate Immune Response Profiling

- For cytokine release, seed and treat cells as in Part A, using a relevant immune cell model like peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or THP-1-derived macrophages.

- After 24 hours of nanoparticle exposure, collect the cell culture supernatant by centrifugation.

- Analyze the supernatant for pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) using a commercial ELISA kit, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- For surface activation marker analysis, harvest the cells after treatment, wash with staining buffer, and stain with fluorescently-labeled antibodies against CD80, CD86, and MHC Class II for 30 minutes on ice in the dark.

- Wash cells and resuspend in staining buffer for analysis by flow cytometry. Compare the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of treated cells to untreated controls to assess immune activation.

Visualizing Workflows and Mechanisms

LNP Formulation and Intracellular Delivery

Diagram Title: LNP Formulation and Delivery Pathway

CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Delivery and Editing

Diagram Title: RNP Delivery and Gene Editing Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Non-Viral Vector Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102) | Core component of LNPs; self-assembles with nucleic acids, enables endosomal escape via proton sponge effect [11] [9]. | pKa ~6.5, biodegradable ester linkages, high fusogenicity. |

| Cationic Polymers (e.g., Polyethylenimine - PEI) | Condenses nucleic acids via electrostatic interaction; common non-viral vector for in vitro transfection [8] [10]. | High positive charge density, proton sponge effect; can be cytotoxic. |

| PEGylated Lipids (e.g., DMG-PEG2000) | Provides a hydrophilic corona on nanoparticles; reduces aggregation, improves stability, and prolongs circulation half-life in vivo [9]. | PEG chain length (e.g., 2000 Da) critical for steric stabilization. |

| Recombinant Cas9 Nuclease | Engineered CRISPR-associated protein; functions as molecular scissors for targeted DNA cleavage in RNP complexes [11] [9]. | High purity, endotoxin-free, nuclear localization signals (NLS), various fidelity versions available. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Single guide RNA; directs Cas9 to specific genomic loci via complementary base pairing [11]. | Chemically modified (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) for enhanced nuclease resistance and reduced immunogenicity. |

| Microfluidic Mixer (e.g., NanoAssemblr) | Enables rapid, reproducible, and scalable mixing of aqueous and organic phases for homogeneous nanoparticle formation [9]. | Precise control over particle size and PDI; compatible with GMP production. |

Non-viral nanoparticle vectors represent a transformative platform in gene therapy, decisively addressing the critical limitations of viral vectors through enhanced safety, scalable manufacturing, and superior cargo flexibility. The structured data, protocols, and visualizations provided in this application note equip researchers with the foundational tools to leverage these advantages. As the field progresses, the convergence of novel biomaterials, advanced targeting strategies, and deep biological insight will undoubtedly expand the therapeutic reach of non-viral gene delivery, enabling more effective and accessible treatments for a broad spectrum of human diseases.

Gene therapy represents a transformative approach for treating genetic disorders, malignancies, and infectious diseases through the targeted introduction, silencing, or precise editing of therapeutic genes [8]. The success of these therapies is fundamentally dependent on delivery vectors that can safely and efficiently transport genetic payloads to target cells. Non-viral nanoparticles have emerged as promising alternatives to viral vectors, offering superior safety profiles, scalability for manufacturing, and structural reconfigurability to accommodate various cargo sizes [8] [14]. This application note provides a comprehensive landscape overview of the primary classes of non-viral nanoparticle vectors, detailing their compositions, mechanisms, applications, and experimental protocols relevant to gene delivery research and therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of Non-Viral Nanoparticle Classes

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Non-Viral Nanoparticle Classes

| Nanoparticle Class | Key Components | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Limitations | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, PEG-lipids [15] | pH-dependent charge reversal; endosomal escape via disruption [15] | High encapsulation efficiency; proven clinical success; biocompatible [16] | Predominant liver tropism; complex optimization [15] | siRNA drugs (Onpattro), mRNA vaccines, CRISPR delivery [15] [1] |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | PEI, PAMAM, PLGA, chitosan [17] | DNA condensation via electrostatic interaction; "proton sponge" endosomal escape [17] | Structural diversity; facile functionalization; sustained release [17] | Potential cytotoxicity; aggregation issues [17] | Cardiovascular disease treatment, cancer therapy [17] |

| Liposomes | Phospholipids, cholesterol [16] | Lipid bilayer encapsulation; membrane fusion [16] | Biocompatibility; hydrophilic/hydrophobic payload capacity [16] | Low nucleic acid encapsulation efficiency [16] | Drug delivery, limited gene therapy applications [16] |

| Inorganic Nanoparticles | Gold, iron oxide, silica [18] | Variable based on material (e.g., magnetic targeting, thermal responsiveness) [18] | Tunable physicochemical properties; diagnostic and therapeutic multifunctionality [18] | Potential long-term toxicity concerns; biodegradability challenges [18] | Imaging, diagnostics, hyperthermia-based therapies [18] |

Composition and Structure-Function Relationships

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)

LNPs represent the most clinically advanced non-viral gene delivery platform, typically consisting of four key lipid components [15]:

Ionizable Lipids: Critical for nucleic acid encapsulation and endosomal escape. These lipids possess a pKa typically between 6.2-6.9, enabling positive charge acquisition in acidic environments for RNA complexation while maintaining neutrality at physiological pH to reduce toxicity [15]. Structurally, they consist of an amine head group connected to hydrophobic tails via biodegradable linkers (ester, ether, or amide bonds) [15].

Phospholipids (e.g., DSPC, DOPE): Stabilize the LNP bilayer structure and contribute to endosomal escape. DSPC is often preferred for siRNA delivery, while DOPE demonstrates superior performance for mRNA encapsulation [15].

Cholesterol: Enhances membrane integrity and stability of LNPs during circulation [15].

PEG-lipids: Constitute approximately 1.5 mol% of formulation but critically impact stability through steric hindrance, reducing aggregation and protein adsorption [15].

Polymeric Nanoparticles

Cationic polymers facilitate nucleic acid complexation through electrostatic interactions between polymer amine groups and nucleotide phosphate groups [17]. Key polymeric systems include:

Polyethylenimine (PEI): Considered the "gold standard" polymeric vector, available in linear and branched architectures. PEI facilitates endosomal escape via the "proton sponge" effect but can exhibit significant cytotoxicity [17].

Polyamidoamine (PAMAM): Dendrimeric structure offering precise molecular architecture for functionalization. Surface modification with targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies) enhances specificity [17].

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA): Biodegradable polyester with excellent biocompatibility, enabling sustained release applications [17].

Liposomes vs. Lipid Nanoparticles

While both are lipid-based systems, fundamental differences exist. Liposomes feature simple phospholipid bilayers with neutral charge, resulting in poor nucleic acid encapsulation efficiency [16]. LNPs incorporate ionizable cationic lipids that enhance RNA interaction and encapsulation while maintaining physiological compatibility [16].

Targeting Strategies and Surface Modification

Table 2: Nanoparticle Surface Modification Strategies for Enhanced Targeting

| Modification Approach | Specific Ligands/Strategies | Mechanism | Target Sites | Impact on Delivery Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Targeting Ligands | Antibodies, peptides, aptamers, small molecules (e.g., folate, galactose) [15] [17] | Receptor-ligand binding promoting cellular uptake | Cell-specific receptors (e.g., asialoglycoprotein receptor for GalNAc) [1] | Enhanced cellular specificity and uptake; reduced off-target effects [15] |

| Stealth Coatings | PEGylation, chitosan [18] | Steric hindrance reducing protein adsorption and immune recognition | Systemic circulation | Prolonged circulation half-life; reduced clearance by mononuclear phagocyte system [18] |

| Formulation Optimization | Component ratio adjustment; novel lipid design [15] | Altering physicochemical properties (size, charge, pKa) | Specific tissues/organs beyond liver | Modulated biodistribution; enhanced endosomal escape [15] |

| Stimuli-Responsive Elements | pH-sensitive lipids, enzyme-cleavable linkers [19] | Payload release triggered by specific biological stimuli | Disease microenvironments (e.g., acidic tumors) | Controlled spatiotemporal release; enhanced therapeutic precision [19] |

Overcoming Biological Barriers

Effective gene delivery requires nanoparticles to overcome multiple biological barriers [16]:

Systemic Barriers: Serum nucleases rapidly degrade naked nucleic acids, while the mononuclear phagocyte system clears circulating nanoparticles. PEGylation creates a hydrophilic "protective barrier" that reduces protein adsorption and extends circulation time [18].

Cellular Barriers: The negatively charged cell membrane repels nucleic acids. Nanoparticles with positive surface charge (zeta potential) facilitate cellular uptake through electrostatic interactions, though excessive positivity increases toxicity [16]. Optimal nanoparticle size (60-100 nm) promotes receptor-mediated endocytosis while avoiding renal clearance (<10 nm) or immune activation (>300 nm) [16].

Intracellular Barriers: Following endocytosis, nanoparticles must escape endosomal compartments before enzymatic degradation. Ionizable lipids and protonable polymers facilitate endosomal membrane disruption through charge reversal in acidic environments [15] [17].

Experimental Protocols

LNP Formulation via Microfluidic Mixing

Principle: Rapid mixing of lipid and aqueous phases induces nanoprecipitation, forming monodisperse LNPs [15].

LNP Formulation Workflow

Materials:

- Ionizable lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102)

- Helper lipids: DSPC, cholesterol

- PEG-lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG 2000)

- Anhydrous ethanol

- mRNA in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.0)

- Microfluidic device (NanoAssemblr, Precision NanoSystems)

- Dialysis membranes (MWCO 100 kDa)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

Procedure:

- Lipid Solution Preparation: Dissolve ionizable lipid, DSPC, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid in ethanol at molar ratio 50:10:38.5:1.5 to achieve total lipid concentration of 10-20 mM [15].

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Dilute mRNA in citrate buffer to concentration of 0.1-0.2 mg/mL.

- Microfluidic Mixing: Set total flow rate (TFR) to 12 mL/min with aqueous-to-organic flow rate ratio (FRR) of 3:1.

- Immediate Dialysis: Dialyze formed LNPs against PBS (pH 7.4) for 4 hours at 4°C to remove ethanol.

- Characterization: Measure particle size (target: 60-100 nm), polydispersity index (PDI <0.2), and encapsulation efficiency (>90%) [16].

Polymer-DNA Polyplex Formation

Principle: Electrostatic complexation between cationic polymer and anionic DNA forms compact nanoparticles [17].

Polyplex Formation Protocol

Materials:

- Branched PEI (25 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich)

- Plasmid DNA (pDNA) encoding therapeutic gene

- HEPES-buffered glucose (HBG, pH 7.4)

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

Procedure:

- Polymer Solution: Prepare PEI at 1 mg/mL in HBG buffer, filter sterilize (0.22 μm).

- DNA Dilution: Dilute pDNA to 0.1 mg/mL in HBG buffer.

- Polyplex Formation: Add polymer solution to DNA solution at specified N/P ratios (typically 5-10:1, amine to phosphate). Vortex immediately for 30 seconds.

- Incubation: Allow polyplex formation to complete by incubating 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Characterization:

- Size and zeta potential: Dynamic light scattering

- Complexation efficiency: Agarose gel electrophoresis retardation assay

- Morphology: Transmission electron microscopy

In Vitro Transfection Efficiency Assessment

Principle: Quantitative measurement of gene expression following nanoparticle-mediated delivery [19].

Materials:

- HEK293 or HeLa cells

- Complete growth medium (DMEM + 10% FBS)

- Reporter plasmid (e.g., eGFP, luciferase)

- Formulated nanoparticles

- Flow cytometer or luminometer

- MTT assay reagents for cytotoxicity

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells in 24-well plates at 50,000 cells/well, incubate 24 hours to reach 70-80% confluency.

- Nanoparticle Treatment: Replace medium with fresh complete medium containing nanoparticles at serial dilutions. Include positive (commercial transfection reagent) and negative (untreated cells) controls.

- Incubation: Incubate cells 24-48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Efficiency Analysis:

- For eGFP expression: Analyze using flow cytometry, reporting percentage of fluorescent cells and mean fluorescence intensity.

- For luciferase expression: Lyse cells, measure luminescence, normalize to protein content.

- Cytotoxicity Assessment: Perform MTT assay parallel to transfection to determine cell viability.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Non-Viral Gene Delivery

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102, ALC-0315 [15] | Core LNP component for nucleic acid encapsulation and endosomal escape | pKa optimization (6.2-6.9); biodegradability via ester bonds [15] |

| Cationic Polymers | PEI (branched, 25kDa), PAMAM dendrimers [17] | DNA condensation; proton sponge endosomal escape | Cytotoxicity concerns; requires structural modification [17] |

| PEG-Lipids | DMG-PEG2000, DSG-PEG2000 [15] | LNP stability; reduced protein adsorption; circulation half-life extension | PEG content optimization (typically 1.5 mol%); potential anti-PEG immunity [15] |

| Helper Lipids | DSPC, DOPE, cholesterol [15] | LNP structural integrity; membrane fluidity modulation | DOPE preferred for mRNA; DSPC for siRNA [15] |

| Targeting Ligands | GalNAc, RGD peptides, transferrin, folate [15] [17] [18] | Cell-specific targeting through receptor recognition | Conjugation chemistry; ligand density optimization [18] |

| Characterization Tools | DLS, zeta potential analyzer, TEM [16] | Nanoparticle physicochemical property assessment | Size (60-100 nm optimal); PDI (<0.2); zeta potential (moderate positive) [16] |

The landscape of non-viral nanoparticles for gene delivery encompasses diverse platforms with complementary strengths and applications. LNPs currently lead clinical translation with proven success in siRNA and mRNA delivery, while polymeric nanoparticles offer extensive functionalization flexibility. Liposomes provide established biocompatibility, and inorganic nanoparticles enable unique theranostic applications. Critical to advancing these platforms is the rational design of nanoparticle composition and surface properties to overcome biological barriers and achieve targeted delivery. The experimental protocols outlined provide foundational methodologies for researchers developing next-generation non-viral gene delivery systems. As these technologies continue to evolve, they hold immense potential to expand the therapeutic reach of gene-based medicines beyond current limitations.

Mechanisms of Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking

The efficacy of non-viral nanoparticle vectors in gene delivery is fundamentally governed by their journey from initial cellular contact to final intracellular destination. Understanding the mechanisms of cellular uptake and subsequent intracellular trafficking is paramount for the rational design of vectors that can overcome biological barriers and achieve therapeutic levels of gene expression. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols to study these critical processes, framed within a thesis investigating poly(beta-amino ester) (PBAE) polymers as model non-viral vectors for glioblastoma gene therapy [20]. The following sections outline the primary internalization pathways, provide a quantitative framework for analyzing plasmid mass transfer, and detail essential reagents and protocols for experimental investigation.

Major Uptake Pathways for Non-Viral Nanoparticles

Non-viral gene complexes, or polyplexes, are internalized via a variety of endocytic and non-endocytic pathways. The dominant route depends on a complex interplay of nanoparticle physicochemical properties and the target cell type [21]. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the key endocytic pathways.

Table 1: Key Endocytic Pathways for Non-Viral Nanoparticle Vectors

| Uptake Pathway | Key Machinery/Features | Typical Cargo Size | Intracellular Fate | Common Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis (CME) | Clathrin coat, dynamin [21] | ~120 nm [21] | Early endosome → late endosome → lysosome [21] | Chlorpromazine, Pitstop 2 [21] |

| Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis (CvME) | Caveolin-1, cholesterol-rich domains, dynamin [21] | ~60 nm [21] | Caveosome → Endoplasmic Reticulum/Golgi [21] | Methyl-β-cyclodextrin, Genistein [21] |

| Macropinocytosis | Actin-driven membrane ruffling, growth factor receptors [21] | >0.5 μm [21] | Macropinosome → lysosome [21] | Amiloride, EIPA [21] |

| Phagocytosis | Professional phagocytes (e.g., macrophages) [21] | >0.5 μm [21] | Phagosome → lysosome [21] | Cytochalasin D [21] |

The following diagram illustrates the major uptake pathways and the subsequent intracellular trafficking of non-viral nanoparticles, highlighting key compartments and fate decisions.

Quantitative Analysis of Cellular and Nuclear Uptake

A critical bottleneck in non-viral gene delivery is the inefficient transport of genetic material from the cell surface into the nucleus. A quantitative, multi-compartment model using flow cytometry and qPCR can be employed to determine the rate constants for each step, thereby identifying the primary barriers for a given vector system [20].

Protocol: Quantifying Uptake Rates via Flow Cytometry and qPCR

This protocol describes a method to track the number of plasmids through different cellular compartments over time to calculate key rate constants.

Materials

- Cells: Human primary glioblastoma cells [20].

- Vector: Poly(beta-amino ester) polymer (e.g., PBAE 447) [20].

- Plasmid DNA: eGFP-N1 plasmid, conjugated with Cy3 fluorescent dye using a Label IT Tracker Kit [20].

- Buffers: Lysis buffer for nucleus isolation, DNase-free PBS.

- Equipment: Flow cytometer, quantitative PCR machine, NanoDrop spectrophotometer.

Procedure

- Polyplex Formation: Formulate polyplexes at an optimal N/P ratio (e.g., 8.0 for PEI/DNA systems [22]) using Cy3-labeled plasmid DNA. Incubate for a standardized time (e.g., 15-30 minutes) at room temperature to allow for complex formation.

- Cell Transfection: Seed cells at a high density (optimized for the cell type). Add polyplexes to the cells and incubate for defined time points (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours).

- Compartmental Separation:

- Total Cellular Uptake: At each time point, trypsinize and wash cells. Analyze by flow cytometry to measure total Cy3 fluorescence, representing plasmids associated with the cell (Pcell).

- Nuclear Envelope Association & Nuclear Uptake: Lyse the cell membrane using a mild detergent buffer, leaving nuclei intact. Isolate nuclei by centrifugation. Resuspend the nuclear pellet and analyze an aliquot by flow cytometry. The Cy3 signal from the intact nuclei represents plasmids associated with the nuclear envelope (Pne) and those internalized (Pni).

- DNA Quantification via qPCR: Treat the remaining nuclear sample with DNase to degrade any externally bound, non-internalized plasmid DNA. Subsequently, lyse the nuclei and isolate the protected internalized plasmid DNA. Quantify the absolute number of plasmids using qPCR with standard curves of known plasmid quantities. This value is Pni.

- Data Calculation:

- The number of plasmids in the cytoplasm (Pcyto) is calculated as: Pcell - Pne.

- The number of nuclear-associated plasmids (Pne) is calculated from the flow cytometry data of the pre-DNase nuclei sample, calibrated against the qPCR data.

Data Analysis and Modeling

The data is fitted to a four-compartment, first-order mass-action model to determine the rate constants [20]:

- Cellular Uptake Rate Constant (kcell): Conversion from extracellular to cytoplasmic plasmid.

- Nuclear Envelope Association Rate Constant (kne): Conversion from cytoplasmic to nuclear envelope-associated plasmid.

- Nuclear Internalization Rate Constant (kni): Conversion from nuclear envelope-associated to nuclear internalized plasmid.

Table 2 provides example quantitative data derived from applying this model to PBAE-based polyplexes in glioblastoma cells.

Table 2: Quantitative Uptake Metrics for PBAE/DNA Polyplexes in Glioblastoma Cells

| Parameter | Description | Quantitative Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| kcell | Cellular Uptake Rate Constant | 7.5 × 10-4 hr-1 [20] | Rate-limiting step for the system. |

| % of Added Dose Internalized | Total Cellular Uptake Efficiency | 0.1% [20] | Very low fraction of dose enters the cell. |

| % of Internalized DNA in Nucleus | Nuclear Delivery Efficiency | 12% [20] | Once inside the cell, nuclear delivery is relatively efficient. |

| kni | Nuclear Internalization Rate Constant | 1.1 hr-1 [20] | Faster than cellular uptake. |

| Plasmid Degradation | Fast-phase rate constant | 0.62 hr-1 [20] | Indicates significant intracellular degradation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3 catalogs key reagents and tools essential for investigating the cellular uptake and trafficking of non-viral gene delivery vectors.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Uptake and Trafficking Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors | To selectively block specific endocytic pathways and determine their contribution to uptake. | Chlorpromazine (CME), Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (CvME), Amiloride (Macropinocytosis) [21]. |

| Fluorescent Plasmid Labels (e.g., Cy3) | To tag genetic cargo for visualization and quantification via fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. | Conjugation to plasmid DNA for tracking cellular and nuclear uptake over time [20]. |

| Gal8-mRuby Reporter System | A live-cell biosensor that fluoresces upon endosomal disruption, directly reporting endosomal escape efficiency. | Screening hundreds of nanoparticle formulations for their ability to escape the endosome and release cargo into the cytosol [23]. |

| Lanthanide-Doped Nanoparticles | Enables quantitative, multiplexed tracking of different nanoparticle formulations simultaneously in a single system. | Comparing biodistribution and tumor delivery of up to 4 different targeted nanoparticles in a single mouse via ICP-MS [24]. |

| 3D Cell Models (Spheroids/Organoids) | Provides a more physiologically relevant model with cell-cell interactions and barriers to penetration, bridging the gap between 2D culture and in vivo. | Studying nanoparticle penetration depth and distribution in a tissue-like context using high-resolution fluorescence microscopy [25]. |

| Metal Chelator-Lipid Conjugates | Allows positron emission tomography (PET) tracking of lipid nanoparticles in live animals and non-human primates. | Visualizing whole-body trafficking of mRNA LNP vaccines, confirming rapid drainage to lymph nodes after intramuscular injection [26]. |

A meticulous, quantitative understanding of the cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking pathways of non-viral nanoparticles is indispensable for advancing gene delivery systems. The application of the protocols and tools detailed herein—from pathway-specific inhibition studies to sophisticated quantitative modeling of plasmid trafficking—enables researchers to identify the specific rate-limiting steps for their vector system. Integrating these insights with advanced models, such as 3D spheroids and multiplexed in vivo tracking, provides a powerful framework for the rational design of next-generation non-viral vectors with enhanced gene delivery efficacy.

Engineering Delivery Platforms: From Lipid Nanoparticles to Inorganic Systems

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as the non-viral vector of choice for the delivery of a wide spectrum of nucleic acid therapeutics, fundamentally advancing the fields of gene silencing and gene editing. [27] [28] Their journey from a delivery vehicle for small interfering RNA (siRNA) to a sophisticated platform for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-based genome editing marks a significant milestone in nanomedicine. LNPs are spherical vesicles, typically 50-120 nm in diameter, composed of a precise mixture of ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEGylated lipids. [27] [29] This unique composition enables them to efficiently encapsulate and protect nucleic acid cargo, facilitate cellular uptake, and promote endosomal escape for functional delivery into the cytoplasm. [27] [28] The clinical validation of LNP technology was catalyzed by the approval of Onpattro (patisiran) in 2018, the first siRNA therapeutic for hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis, and its prominence was further solidified by the global deployment of LNP-formulated mRNA vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic. [30] [31] [32] This application note details the evolution, current applications, and detailed protocols for utilizing LNPs in siRNA and CRISPR delivery, providing a practical resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

LNP Fundamentals: Composition and Mechanism of Action

The functional properties of LNPs are dictated by their core components, each playing a critical role in structure, stability, and delivery efficiency.

- Ionizable Lipids: The most critical component, these lipids are positively charged at low pH (enabling efficient RNA encapsulation during formulation) but neutral at physiological pH (reducing toxicity). They are also instrumental in mediating endosomal escape through a charge-based mechanism. [27] [29]

- Structural Lipids (e.g., DSPC): These phospholipids contribute to the structural integrity of the LNP bilayer, mimicking natural cell membranes and enhancing fusion with cellular membranes. [29]

- Cholesterol: A stability-enhancing component that fills gaps between lipid molecules, increases membrane rigidity, and improves circulation time. [29]

- PEGylated Lipids: These lipids control particle size and prevent aggregation during storage and in circulation by providing a hydrophilic exterior. They also reduce nonspecific interactions and can influence pharmacokinetics. [27] [29]

The mechanism of LNP-mediated delivery follows a multi-step process: First, the LNP protects its nucleic acid payload from degradation in the bloodstream. Following cellular uptake via endocytosis, the acidic environment of the endosome protonates the ionizable lipids, disrupting the endosomal membrane and releasing the cargo into the cytoplasm, where it can execute its function. [27] [28]

→ Diagram: LNP-Mediated Nucleic Acid Delivery Pathway

LNP Delivery of siRNA Therapeutics

Mechanism and Clinical Success

siRNAs are short double-stranded RNA molecules that harness the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway to selectively silence gene expression. [31] The siRNA is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where the guide strand directs RISC to complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) sequences. This leads to the cleavage and degradation of the target mRNA, preventing protein translation. [31] [32] LNPs overcome the major hurdles of siRNA delivery, including enzymatic degradation, renal clearance, and inefficient cellular uptake. [31] The success of this approach is demonstrated by several FDA-approved drugs, with more in clinical trials.

Table 1: FDA-Approved LNP-delivered siRNA Therapeutics

| Therapeutic (Brand Name) | Target / Indication | Key Clinical Trial & Outcome | Approval Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patisiran (Onpattro) [30] [32] | Transthyretin (TTR) / hATTR Amyloidosis | Phase III (APOLLO): Improved neuropathy scores [30] | 2018 [31] [32] |

| Givosiran (Givlaari) [30] [32] | Aminolevulinic Acid Synthase 1 / Acute Hepatic Porphyria | Phase III (ENVISION): Reduced porphyria attacks [30] | 2019 [32] |

| Inclisiran (Leqvio) [30] | PCSK9 / Hypercholesterolemia | Phase III (ORION): Sustained LDL-C reduction [30] | 2021 [30] |

Protocol: Formulating siRNA-LNPs for Antiviral Applications

Preclinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of LNP-delivered siRNA against various viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. [31] The following protocol is adapted from these studies.

Materials:

- siRNA: Chemically modified (e.g., 2'-F, 2'-O-Me) for stability. [31]

- Lipids: Ionizable lipid (e.g., ALC-0315), DSPC, Cholesterol, PEG-lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG2000). [27] [29]

- Buffers: 10 mM Citrate buffer (pH 4.0), 1x PBS (pH 7.4).

- Equipment: Microfluidic mixer (e.g., NanoAssemblr), PD-10 desalting columns, Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) instrument.

Procedure:

- Lipid Stock Preparation: Prepare individual ethanolic stocks of the lipids. Combine at a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5 (Ionizable Lipid:DSPC:Cholesterol:PEG-lipid). [31] [28]

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Dilute the siRNA in citrate buffer (pH 4.0) to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL.

- Nanoparticle Formation: Using a microfluidic mixer, rapidly mix the ethanolic lipid solution with the aqueous siRNA solution at a fixed flow rate ratio (typically 3:1 aqueous-to-ethanol) to form LNPs. [28]

- Buffer Exchange & Dialysis: Dialyze the formed LNP suspension against a large volume of 1x PBS (pH 7.4) for at least 4 hours at 4°C to remove ethanol and adjust the pH.

- Characterization:

- Particle Size & PDI: Measure by DLS. Target size: 80-100 nm.

- Encapsulation Efficiency: Quantify using a Ribogreen assay. >90% encapsulation is desirable.

- siRNA Integrity: Verify by gel electrophoresis.

Advancing to CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing with LNP Delivery

The Shift from siRNA to CRISPR Payloads

The modularity of LNPs allows them to be adapted for larger and more complex payloads, most notably for CRISPR-Cas genome editing. [27] CRISPR systems can be delivered in multiple formats, each with distinct advantages. While viral vectors are limited by immunogenicity, payload size, and persistent expression, LNP delivery offers a transient, scalable, and less immunogenic alternative. [27] [33]

Table 2: Comparison of CRISPR Formats for LNP Delivery

| CRISPR Format | Components Delivered | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| plasmid DNA (pDNA) [29] | DNA encoding Cas9 and gRNA | Simpler formulation. | Low efficiency; requires nuclear entry; prolonged expression increases off-target risk. [27] |

| mRNA + gRNA [29] | mRNA encoding Cas9 protein + guide RNA | Transient expression; higher efficiency than pDNA. | mRNA immunogenicity; co-encapsulation of two RNA species is complex. [27] |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) [33] [29] | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and gRNA | Highest safety profile; rapid activity; minimal off-target effects. | Formulation challenges due to protein sensitivity and low negative charge. [33] |

A landmark 2025 study published in Nature Biotechnology demonstrated the power of LNP-delivered RNPs. Researchers engineered a thermostable Cas9 (iGeoCas9) that could withstand LNP formulation stresses. Using tissue-selective LNP formulations, they achieved 19% editing efficiency of the disease-causing SFTPC gene in mouse lung tissue and 31% editing of PCSK9 in the liver after a single intravenous injection, showcasing the therapeutic potential of this approach. [33]

Protocol: Assembling CRISPR RNP-LNPs for In Vivo Editing

This protocol is based on the successful methodology for delivering iGeoCas9 RNPs. [33]

Materials:

- CRISPR RNP: Purified iGeoCas9 (or SpyCas9) protein complexed with synthetic sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:1.2.

- Specialized Lipids: Include a pH-sensitive PEGylated lipid and a biodegradable cationic lipid for enhanced lung targeting. [33]

- Other reagents: Nuclease-free water, Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS).

Procedure:

- RNP Complex Formation: Incubate the Cas9 protein with a 1.2-fold molar excess of sgRNA in nuclease-free buffer for 10 minutes at room temperature to form the RNP complex.

- Lipid Mixture Preparation: Prepare an ethanolic solution of lipids. For lung-tropic delivery, a formulation incorporating ~10 mol% of a biodegradable cationic lipid (e.g., a SORT molecule) is effective. [33] [29]

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Dilute the pre-formed RNP complex in citrate buffer (pH 4.0).

- LNP Formulation: Use a microfluidic device to mix the ethanolic lipids with the aqueous RNP solution at a high total flow rate (≥ 12 mL/min) to form stable RNP-LNPs.

- Purification and Characterization: Dialyze against DPBS. Characterize particles for size, PDI, and encapsulation efficiency. Critical Note: Use a microfluidics-based method specifically optimized for proteins to avoid denaturation. [33]

→ Diagram: CRISPR RNP-LNP Assembly Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for LNP Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LNP Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in LNP Formulation | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | Core structural component; enables encapsulation and endosomal escape. | ALC-0315 (Comirnaty), SM-102 (Spikevax). Newer thermostable variants support RNP delivery. [27] [33] [29] |

| PEGylated Lipids | Stabilizes particle size; reduces aggregation; modulates PK/PD. | DMG-PEG2000, DSPE-PEG2000. Molar ratio critical for controlling particle size and in vivo performance. [27] [29] |

| Structural Lipids | Enhances LNP bilayer stability and integrity. | DSPC, DOPE. Helps facilitate fusion with endosomal membranes. [29] |

| Cholesterol | Enhances stability and fluidity of the LNP membrane. | Molecular "filler" that improves packing and resilience in serum. [29] |

| SORT Molecules | Enables targeted delivery to specific tissues beyond the liver. | Adding a quaternary ammonium (cationic) lipid can redirect LNPs to the lungs. [33] [29] |

| Nucleic Acid Payloads | The therapeutic cargo. | siRNA: Chemically modified for stability. [31] sgRNA: Synthetic, high-purity. Cas9 mRNA/RNP: Codon-optimized mRNA or purified protein. [33] [29] |

LNPs have proven to be a transformative platform, enabling the clinical success of siRNA therapeutics and paving the way for the next generation of CRISPR-based gene therapies. The evolution from siRNA to RNP delivery, as demonstrated by recent breakthroughs in lung and liver editing, highlights the adaptability and power of LNP technology. [33] Future developments will focus on overcoming remaining challenges, including enhancing delivery to extrahepatic tissues through advanced targeting strategies (e.g., SORT molecules, ligand conjugation), improving the scalability and cost-effectiveness of manufacturing, and thoroughly understanding long-term safety profiles. [27] [34] [28] As the field progresses, the integration of AI-driven design for novel lipids and LNP formulations promises to further accelerate the development of precise and personalized genetic medicines. [30] [35] The protocols and insights provided here offer a foundation for researchers to leverage LNPs in their pursuit of novel genetic therapeutics.

Polymer-based vectors represent a promising class of non-viral delivery systems for genetic material, offering a compelling alternative to viral vectors by potentially mitigating immunogenicity concerns while providing tunable physicochemical properties. These vectors are engineered to navigate the complex intracellular environment, effectively encapsulating and protecting nucleic acids such as plasmid DNA, mRNA, and siRNA, and facilitating their delivery into target cells. The fundamental challenge in their design lies in optimizing two often competing characteristics: high transfection efficiency and favorable biocompatibility. Achieving this balance requires meticulous molecular engineering of polymer structures to control their interactions with biological systems, from cellular membranes to intracellular compartments.

The versatility of synthetic polymers allows for systematic modifications to their backbone, side chains, and functional groups, enabling fine-tuning of critical parameters including molecular weight, charge density, hydrophobicity, and degradation kinetics. Within the broader context of non-viral nanoparticle vectors research, polymer-based systems stand out for their scalability, reproducibility, and capacity for functionalization with targeting ligands. This application note provides a detailed technical overview of recent advances in polymer vector design, quantitative performance data, and standardized protocols to support researchers in developing next-generation gene delivery systems for therapeutic applications.

Quantitative Performance of Advanced Polymer Vectors

Recent research has yielded significant improvements in polymer vector performance, with novel materials demonstrating enhanced transfection efficiency and reduced cytotoxicity. The following tables summarize key quantitative data from cutting-edge studies for easy comparison of vector characteristics.

Table 1: Transfection Efficiency and Cytotoxicity of Featured Polymer Vectors

| Polymer Vector | Nucleic Acid Delivered | Cell Line / Model | Transfection Efficiency | Cytotoxicity (Cell Viability) | Key Structural Feature | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DP50-PE6 (POx) | mRNA (Fluc) | 293T cells (in vitro) | 3.3 × 105-fold increase vs. parent polymer | Maintained high viability | PAmOx backbone with C10 alkyl chains from 1,2-epoxydecane | [36] |

| DP50-PE6 (POx) | mRNA (OVA) | B16-OVA melanoma (in vivo) | >90% tumor suppression (with anti-PD1) | Good biocompatibility observed | Spleen-targeting after IV administration | [36] |

| PBAE Nanocarriers | Plasmid DNA | Jurkat T cells | Up to 37% transfection | Minimal cytotoxicity | Low molecular weight, biodegradable | [37] |

| PBAE Nanocarriers | Plasmid DNA | Primary T cells | ~5% transfection | Minimal cytotoxicity | Optimized DNA-to-polymer ratio | [37] |

| OM-pBAE (Coated AAV) | Transgene for DMD | In vitro & in vivo DMD model | Superior transduction efficiency | Improved protection vs. neutralizing antibodies | Polymer coating evades immune response | [38] |

| STAR-CXP (Polyaminoacid) | pDNA, siRNA, saRNA | Comparative in vitro | Up to 9× higher than jetPEI | Reduced immunogenicity in human serum | Biodegradable, nuclear localization | [39] |

Table 2: Physicochemical Properties and Formulation Parameters

| Polymer Vector | Typical Formulation N/P Ratio | Polyplex/Particle Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | Key Administration Routes Tested | Optimal DP / Mw |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DP50-PE6 (POx) | ~30/1 (mass ratio) | Not specified | Not specified | Intravenous, Intramuscular | DP 50 |

| PBAE Nanocarriers | Varied DNA-to-polymer ratios | Characterized for size and dispersion | Characterized for surface charge | Ex vivo T cell transfection | Low Mw |

| STAR-CXP | System-dependent | Stable nanoparticles, resists aggregation | Reduced surface charge with PSar shielding | Intravenous, Intramuscular | Not specified |

| PEI (Benchmark) | System-dependent | Varies with formulation | Highly positive (↓ with shielding) | Intratumoral, Intramuscular (non-systemic) | Broad Mw ranges |

The data in Table 1 highlights remarkable achievements in vector performance. The POx-based vector DP50-PE6 demonstrates an extraordinary 330,000-fold enhancement in mRNA transfection efficiency over its parent polymer, underscoring the profound impact of strategic hydrophobic modification [36]. Similarly, PBAE nanocarriers achieve notable transfection in hard-to-transfect primary T cells, a critical milestone for cell-based immunotherapies [37]. The >90% tumor suppression rate achieved by DP50-PE6 in a melanoma model, combined with the spleen-targeting capability observed after intravenous administration, positions this polymer as a particularly promising platform for mRNA vaccines and cancer immunotherapies [36].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Formulation of POx-Based Polyplexes for mRNA Delivery

This protocol outlines the synthesis of amino-functionalized poly(2-oxazoline) (POx) vectors and their complexation with mRNA, based on the highly effective DP50-PE6 polymer [36].

Reagents and Materials:

- Poly[2-(5-aminopentyl)-2-oxazoline] (PAmOx50, DP = 50)

- 1,2-epoxydecane (E6)

- Anhydrous Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) or Tetrahydrofuran (THF)

- mRNA of interest (e.g., encoding Firefly Luciferase or antigen)

- Nuclease-free water

- 1x Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Equipment: Schlenk flask, Magnetic stirrer, Purification system (dialysis or SEC), Heated water bath, Vortex mixer, Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) instrument.

Procedure:

- Polymer Synthesis (DP50-PE6): a. Reaction Setup: In a Schlenk flask under an inert atmosphere, dissolve PAmOx50 (1.0 g, ~20 µmol) in 10 mL of anhydrous DMSO. b. Epoxide Modification: Add 1,2-epoxydecane (E6, 10 mol equivalent per amine group) to the reaction mixture. c. Polymer Modification: Stir the reaction mixture at 60°C for 48 hours to allow for the ring-opening reaction between the primary amines of PAmOx and the epoxide groups. d. Purification: Purify the resulting DP50-PE6 polymer by dialysis against ethanol or methanol for 24 hours, followed by lyophilization. Alternatively, use size exclusion chromatography. e. Characterization: Confirm the chemical structure and grafting efficiency by ¹H NMR spectroscopy [36].

- Polyplex Formation (Complexation): a. Polymer Solution: Prepare a stock solution of DP50-PE6 in nuclease-free water or PBS at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. Filter sterilize (0.22 µm). b. mRNA Solution: Dilute the mRNA to a working concentration of 0.05 mg/mL in nuclease-free PBS. c. Complexation: Add the desired volume of the polymer solution to an equal volume of the mRNA solution to achieve a polymer-to-mRNA mass ratio of 30:1. For example, mix 30 µL of polymer stock (1 mg/mL) with 1 µL of mRNA stock (0.05 mg/mL) and 29 µL of PBS. Gently vortex the mixture for 3-5 seconds. d. Incubation: Allow the polyplexes to form by incubating the mixture at room temperature for 20-30 minutes. The solution may turn slightly opaque. e. Quality Control: Characterize the resulting polyplexes for size (hydrodynamic diameter) and surface charge (zeta potential) using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) prior to use.

Protocol: Transfection of Adherent Cells (293T) with POx/mRNA Polyplexes

This protocol describes the in vitro transfection of human embryonic kidney (293T) cells to evaluate the performance of the formulated polyplexes [36].

Reagents and Materials:

- DP50-PE6/mRNA polyplexes (from Protocol 3.1)

- 293T cell line

- Complete growth medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS)

- Opti-MEM or serum-free medium

- Trypsin-EDTA solution

- 96-well or 24-well tissue culture plates

- Equipment: Cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂), Laminar flow hood, Centrifuge, Microplate reader or luminescence detector.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed 293T cells in a 96-well plate at a density of 1.0 x 10⁴ cells per well in 100 µL of complete growth medium. Incubate the plate for 18-24 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ incubator until the cells reach 60-80% confluency.

- Transfection Medium Exchange: Before transfection, carefully aspirate the growth medium and wash the cell monolayer once with PBS. Replace the medium with 100 µL of Opti-MEM or serum-free medium.

- Polyplex Application: Add the pre-formed DP50-PE6/mRNA polyplexes (e.g., 10 µL per well from a 60 µL total preparation) directly to the cells in serum-free medium. Gently swirl the plate to ensure even distribution.

- Incubation and Expression: Incubate the cells with the polyplexes for 4-6 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ incubator.

- Post-Transfection Medium Exchange: After the incubation period, carefully aspirate the transfection mixture and replace it with 100 µL of fresh complete growth medium. Continue to incubate the cells for a further 24-48 hours to allow for protein expression.

- Efficiency Analysis: a. Luciferase Expression: If the mRNA encodes luciferase, lyse the cells using a passive lysis buffer and measure luminescence intensity using a microplate reader according to the luciferase assay system manufacturer's instructions. Normalize the relative light units (RLU) to the total protein content in the lysate (RLU/mg protein) [36]. b. Viability Assessment: Perform a parallel MTT or Alamar Blue assay to assess cell viability 24 hours post-transfection to ensure biocompatibility.

Protocol: T Cell Transfection using PBAE Nanocarriers

This protocol details the use of biodegradable Poly(β-amino ester) (PBAE) nanocarriers for transfecting Jurkat and primary T cells, a key step in cell-based cancer immunotherapy [37].

Reagents and Materials:

- Low molecular weight PBAE polymer (synthesized via Michael addition)

- Plasmid DNA (e.g., encoding GFP or CAR construct)

- Jurkat T cell line or isolated primary human T cells

- RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and GlutaMax

- Interleukin-2 (IL-2) for primary T cell culture

- Anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for T cell activation

- Opti-MEM medium

- Equipment: Flow cytometer, Confocal microscope, Cell culture incubator.

Procedure:

- Nanocarrier Formulation: a. Polymer Solution: Dissolve PBAE polymer in DMSO at 100 mg/mL, then dilute in acetate buffer (pH 5.0) to a final concentration of 1-5 mg/mL. b. DNA Solution: Dilute plasmid DNA in the same acetate buffer. c. Complexation: Rapidly mix the PBAE solution with the DNA solution at various DNA-to-polymer mass ratios (e.g., 1:10 to 1:50). Vortex for 30 seconds. d. Incubation: Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 15-30 minutes to allow for nanocarrier self-assembly. e. Characterization: Measure the size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential of the nanocarriers using DLS [37].

T Cell Preparation and Transfection: a. Cell Culture: Maintain Jurkat cells or isolated primary T cells in RPMI-1640 complete medium. For primary T cells, activate with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies and add IL-2 (e.g., 100 IU/mL) 48 hours prior to transfection. b. Transfection: Harvest the cells, count them, and resuspend them in Opti-MEM at a density of 1-2 x 10⁶ cells/mL. c. Nanocarrier Application: Add the formulated PBAE nanocarriers to the cell suspension. Use a DNA mass of 1-2 µg per 1 x 10⁶ cells. d. Incubation: Incubate the cell-nanocarrier mixture for 4-6 hours at 37°C. e. Recovery: Centrifuge the cells to remove the transfection mixture, resuspend them in fresh complete medium (with IL-2 for primary cells), and continue culture for 24-72 hours.

Efficiency and Viability Assessment: a. Flow Cytometry: Analyze transfection efficiency by measuring the percentage of GFP-positive cells using flow cytometry 24-48 hours post-transfection. b. Viability: Assess cell viability simultaneously using a flow cytometry-based assay (e.g., propidium iodide exclusion) or a metabolic assay like MTT.

Visualization of Polymer Vector Design and Workflow

The strategic design of polymer vectors involves creating a molecular structure that can navigate each step of the intracellular delivery pathway. The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core design logic and a standard experimental workflow.

Polymer Vector Design Logic

Diagram 1: Logic of functional polymer vector design. Strategic modifications to a polymer backbone impart specific functionalities that address each barrier to efficient and safe gene delivery, ultimately achieving the goal of balanced performance. POx: Poly(2-oxazoline); PBAE: Poly(β-amino ester); PEI: Polyethylenimine; PSar: Polysarcosine.

Experimental Workflow for Evaluation

Diagram 2: Key stages of polymer vector development. The workflow progresses linearly from synthesis to in vivo evaluation, with critical quantitative analyses performed at each stage to inform iterative design improvements. DLS: Dynamic Light Scattering; PDI: Polydispersity Index.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful development and testing of polymer-based gene delivery systems require a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for a research program in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Polymer-Based Gene Delivery

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cationic Polymers | Forms core of delivery vector; condenses nucleic acids via electrostatic interactions. | PAmOx (starting material for POx vectors) [36], PBAE (biodegradable) [37], PEI (benchmark, high cytotoxicity) [39]. |

| Hydrophobic Modifiers | Enhances membrane interaction and promotes endosomal escape, boosting transfection. | 1,2-epoxydecane (E6) for modifying POx amines [36]. Other alkyl epoxides or acrylates. |

| Shielding Polymers | "Stealth" coating to reduce polyplex charge, prevent aggregation, and lower immunogenicity. | Polysarcosine (PSar) [39], Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Poly(2-oxazoline). |

| Nucleic Acid Cargos | The therapeutic or reporter genetic material to be delivered. | mRNA (e.g., Fluc, OVA) [36], Plasmid DNA (e.g., encoding GFP, CAR) [37], siRNA. |

| Formulation Buffers | Medium for polyplex self-assembly; pH and ionic strength critically impact particle properties. | Acetate Buffer (pH 5.0) for PBAE nanocarriers [37], PBS (pH 7.4), nuclease-free water. |

| Characterization Tools | To measure key physicochemical properties of the formulated nanocarriers. | DLS/Zeta Potential Analyzer for size and surface charge [37]. ¹H NMR for polymer structure confirmation [36]. |

| Cell Culture & Assays | Biological systems and tools to evaluate transfection performance and safety. | Cell Lines (e.g., 293T [36], Jurkat [37]). Primary T cells [37]. Luciferase Assay Kit, Flow Cytometer, MTT/XTT Viability Assay. |

The field of gene therapy is rapidly evolving, offering promising strategies for treating genetic disorders, cancers, and infectious diseases by introducing, silencing, or editing therapeutic genes. A significant challenge in this domain is developing safe and efficient vectors for delivering genetic materials such as DNA, mRNA, siRNA, and miRNA into target cells. While viral vectors demonstrate high transfection efficiency, their clinical application faces substantial hurdles including immunogenicity, insertional mutagenesis risks, limited gene cargo capacity, and complex manufacturing processes [40] [8]. Inorganic nanoparticles have emerged as promising non-viral vectors that can effectively overcome these limitations.

Gold, silica, and carbon-based nanoparticles offer distinct advantages for gene delivery applications, including superior safety profiles, scalability for manufacturing, structural and functional reconfigurability, and the ability to accommodate various sizes of genetic cargo [8] [17]. Their tunable physicochemical properties, ease of functionalization, and excellent biocompatibility make them particularly valuable for creating targeted delivery systems that can navigate biological barriers and efficiently transport genetic payloads to specific cells and even subcellular compartments [41] [42]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the current advances and experimental protocols for utilizing these inorganic nanoparticles in gene delivery systems, framed within the broader context of non-viral vector research.

Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) in Gene Delivery

Application Notes