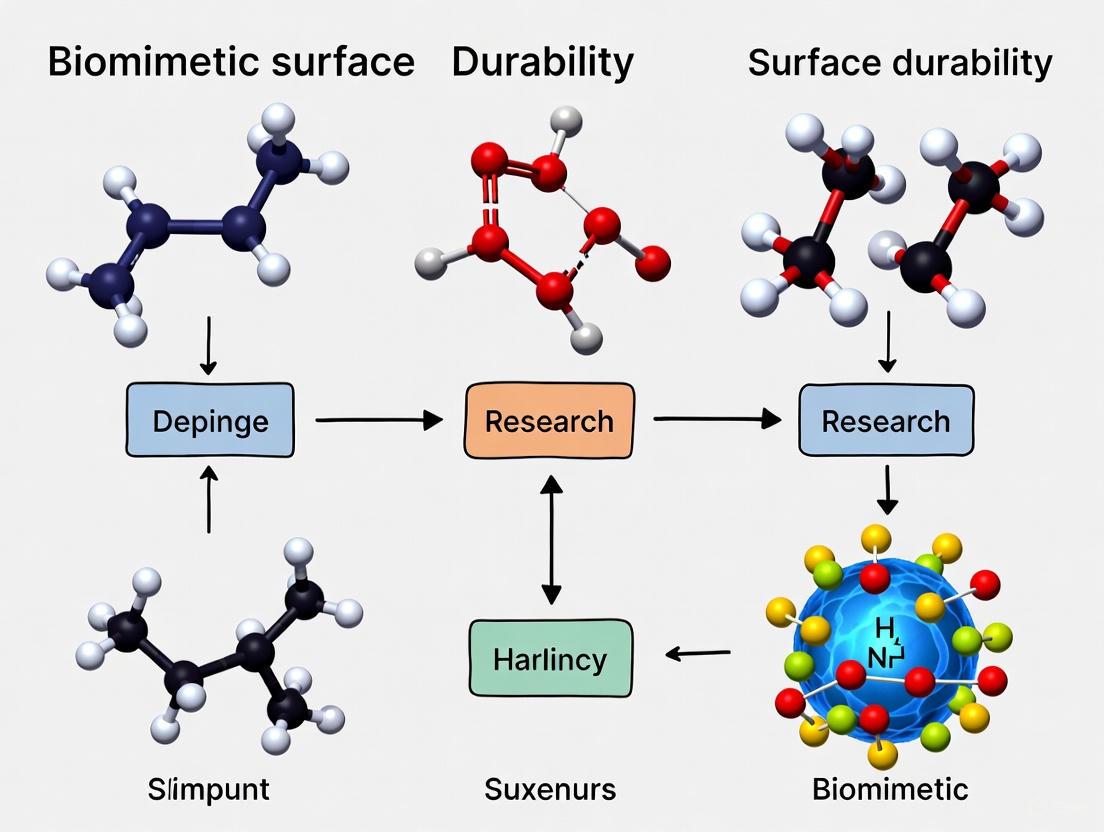

Optimizing Biomimetic Surface Durability: From Natural Blueprints to Robust Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for enhancing the mechanical and chemical durability of biomimetic surfaces, a critical challenge limiting their clinical translation.

Optimizing Biomimetic Surface Durability: From Natural Blueprints to Robust Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for enhancing the mechanical and chemical durability of biomimetic surfaces, a critical challenge limiting their clinical translation. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental principles of durable natural designs, advanced fabrication methodologies, and systematic troubleshooting approaches. By integrating the latest research on superhydrophobic and superamphiphobic surfaces, we present a validation framework for comparing surface performance and longevity. The review synthesizes key insights into designing next-generation, durable biomimetic coatings and materials for biomedical devices, implants, and drug delivery systems, offering a clear pathway from laboratory innovation to robust clinical application.

Learning from Nature: The Blueprint for Durable Liquid-Repellent Surfaces

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between the Wenzel and Cassie-Baxter states?

The Wenzel state describes a regime where the liquid droplet completely penetrates and wets the roughness features of a solid surface. This state amplifies the inherent wettability of the solid material; hydrophilic surfaces become more hydrophilic, and hydrophobic surfaces become more hydrophobic [1] [2]. The apparent contact angle is described by the Wenzel equation: cosθw = r * cosθY, where r is the surface roughness factor (the ratio of the actual surface area to the projected area) and θY is the Young's contact angle [3] [4].

In contrast, the Cassie-Baxter state describes a regime where the liquid droplet sits atop surface asperities, trapping air pockets beneath it. This composite solid-air-liquid interface is crucial for achieving extreme liquid repellency, such as superhydrophobicity [1] [5]. The apparent contact angle is given by the Cassie-Baxter equation: cosθc = σ₁(cosθY + 1) - 1, where σ₁ is the fraction of the solid surface in contact with the liquid [1] [6].

2. Why is my superhydrophobic surface losing its properties over time, and how can I improve its durability?

The loss of superhydrophobicity is a primary challenge in biomimetic surface design. The main reasons for performance degradation are [3]:

- Mechanical damage: The fragile micro/nanostructures that trap air pockets are easily destroyed by abrasion or mechanical stress.

- Unstable air film: The Cassie-Baxter state can be metastable, and the air film may collapse under pressure, vibration, or prolonged contact with liquid, leading to an irreversible transition to the Wenzel state [7].

- Chemical degradation: Surface chemistry can be altered by exposure to acids, alkalis, or ultraviolet radiation, reducing the intrinsic hydrophobicity.

Strategies to enhance durability include [3]:

- Designing self-similar hierarchical structures that preserve air pockets even after partial damage to the nanoscale features.

- Incorporating self-healing materials that can recover low surface energy after chemical degradation.

- Enhancing adhesion between the coating and the substrate to prevent delamination.

- Using robust material systems that resist mechanical wear.

3. My experimental contact angle measurements do not match the values predicted by the Wenzel or Cassie-Baxter equations. Why?

Several factors can cause this discrepancy:

- Contact Angle Hysteresis (CAH): The theoretical equations predict an equilibrium contact angle, but real surfaces exhibit a range of possible angles between the advancing (

θa) and receding (θr) angles due to surface heterogeneity and roughness [5] [4]. The measured static angle often falls within this hysteresis range. - Imperfect Surface Structure: The models assume idealized, uniform roughness. In reality, surfaces may have defects or non-uniform patterns that prevent the perfect Wenzel or Cassie-Baxter state from being realized [2].

- Incorrect Model Application: The droplet may be in an intermediate wetting state that is not purely Wenzel or Cassie-Baxter [7]. Furthermore, it has been shown that the contact angle is determined by the interactions at the three-phase contact line, not the entire interfacial area beneath the droplet [2] [6]. Applying the area-averaged equations in such cases can lead to errors.

4. How can I actively control or tune surface wettability in my experiments?

Beyond creating static surfaces, wettability can be dynamically regulated using external stimuli [5]:

- Electric Fields: Electrowetting can directly reduce the contact angle by modifying the solid-liquid interfacial tension.

- Thermal Fields: Temperature changes can alter the surface tension of the liquid itself or trigger conformational changes in temperature-responsive polymers grafted on the surface.

- Light: Surfaces functionalized with photochromic molecules can switch their wettability upon irradiation with specific wavelengths of light.

- Magnetic Fields: Using magnetic fluids or incorporating magnetic particles into the droplet allows for manipulation via magnetic fields.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Contact Angle Measurements

Symptoms: High variation in contact angle values across the same sample; large difference between advancing and receding angles.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Chemical Heterogeneity | Perform elemental analysis (e.g., EDX) or chemical mapping (e.g., FT-IR) across the surface [8]. | Improve synthesis or coating protocol to ensure uniform surface chemistry. |

| Non-Uniform Roughness | Characterize surface topography using SEM or AFM at multiple locations [9]. | Optimize the texturing process (e.g., micro-milling, etching) for consistency [9]. |

| Contact Angle Hysteresis | Measure both advancing (θa) and receding (θr) contact angles to quantify hysteresis [5]. |

Design surfaces with lower pinning sites (e.g., more regular patterns, reduced chemical defects) to minimize CAH. |

Problem 2: Failure to Achieve Superhydrophobicity

Symptoms: Contact angle remains below 150°; droplets do not roll off the surface.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Roughness | Check surface morphology via SEM/FE-SEM to confirm the presence of micro/nano hierarchical structures [3] [8]. | Introduce dual-scale roughness (e.g., micropillars coated with nanoparticles) to enhance air entrapment [1] [3]. |

| Surface Chemistry not Hydrophobic Enough | Measure the contact angle on a flat surface made of the same material. If θY is low, superhydrophobicity is impossible [3]. |

Apply a low-surface-energy coating (e.g., fluorosilanes) to increase the intrinsic contact angle θY [3]. |

| Wenzel State instead of Cassie-Baxter | Observe if the droplet appears to be sitting on (Cassie) or sinking into (Wenzel) the structures. Test droplet adhesion [7]. | Redesign surface topography to favor the Cassie-Baxter state, e.g., by creating re-entrant structures [3] [5]. |

Problem 3: Poor Durability of Super-Repellent Surfaces

Symptoms: Performance degrades after abrasion, immersion in liquids, or exposure to UV light.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak Mechanical Strength of Structures | Perform abrasion tests and observe surface morphology post-test to identify structural damage. | Use harder materials or create structures from bulk materials rather than coatings (e.g., micro-milling a polymer) [9]. |

| Chemical Instability | Expose the surface to relevant chemicals/UV and re-measure contact angle and surface chemistry [3]. | Employ chemically inert materials or self-healing coatings that can replenish the low-surface-energy layer [3]. |

| Unstable Cassie-Baxter State | Apply external pressure or vibration to the droplet and observe if wetting transitions occur [6] [7]. | Design more robust microstructures with features like overhangs ("re-entrant" curvature) to stabilize the composite interface [3] [5]. |

Quantitative Data and Model Comparison

The following table summarizes the core equations that form the foundation of surface wettability.

Table 1: Summary of Fundamental Wettability Models

| Model | Applicable Surface | Key Equation | Parameters | Critical Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Equation [1] [5] | Ideal, smooth, homogeneous, rigid | cosθY = (γSV - γSL)/γLV |

θY: Young's contact angleγSV, γSL, γLV: Interfacial tensions |

Defines the intrinsic wettability. Maximum θY on smooth surfaces is ~120° [3]. |

| Wenzel Model [2] [4] | Rough, chemically homogeneous | cosθw = r * cosθY |

r: Roughness factor (r ≥ 1) |

Amplifies natural wettability. Roughness makes hydrophilic surfaces more hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces more hydrophobic [1]. |

| Cassie-Baxter Model [1] [6] | Rough, heterogeneous (composite) | cosθc = σ₁cosθY - σ₂ or cosθc = σ₁(cosθY + 1) - 1 |

σ₁: Solid fractionσ₂: Air fraction (σ₂ = 1 - σ₁) |

Enables super-repellency by minimizing solid-liquid contact (σ₁) and leveraging air (cosθair = -1) [1] [5]. |

Table 2: Experimental Contact Angle Data from Recent Studies

| Surface Treatment / Material | Initial Contact Angle | Final Contact Angle After Treatment | Key Change | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz aged with crude oil (Sandstone reservoir) | 50° (pure quartz) | 107° (oil-wet) | Adsorption of polar oil components alters wettability. | [8] |

| Oil-wet quartz treated with Fe3O4 Nanofluid | 107° | 46.21° | Disjoining pressure from nanoparticles reforms water-wet state. | [8] |

| Oil-wet quartz treated with Fe3O4/Gelatin NC | 107° | 25.13° | Nanocomposite creates new interactions, significantly increasing hydrophilicity. | [8] |

| Polypropylene (PP) with biomimetic relief | 98.7° (flat) | 108.3° (structured) | Micro-milled hydrophobic topology (inspired by Hibiscus) enhances θ. |

[9] |

| Polyamide (PA) with biomimetic relief | ~80° (flat, estimated) | Reduced by up to 12% (structured) | Hydrophilic moss-inspired structure further reduces θ on a hydrophilic polymer. |

[9] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Replicating Biomimetic Microstructures via Micro-Milling and Injection Molding

This protocol is adapted from recent research on manufacturing functional polymer surfaces [9].

Objective: To create polymer surfaces with controlled wettability by replicating natural topologies using micro-machining and injection molding.

Materials and Equipment:

- CAD Software (e.g., Autodesk Inventor, Fusion 360)

- Micro-milling Machine (e.g., 3-axis vertical milling center with high spindle speed >10,000 rpm)

- Mold Inserts (typically steel or aluminum)

- Injection Molding Machine

- Polymer Materials (e.g., Polypropylene (PP), Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS), Polyamide (PA 6.6))

- Contact Angle Goniometer

Methodology:

- Topology Design: Model the desired biomimetic microstructure (e.g., cone-shaped for hydrophobicity from Hibiscus trionum, wave-shaped for hydrophilicity from Hypnum cupressiforme) in CAD software [9].

- Micro-Milling: Machine the inverse of the designed topology into a metal mold insert using micro-milling. Key parameters include profile depth (e.g., 100-150 µm), spacing between elements, and tool geometry. Note that tool wear is significant at this scale [9].

- Injection Molding: Produce test samples by injecting polymer into the mold. Critically control processing parameters:

- Melt Temperature: Systematically vary (e.g., 200-310°C depending on polymer).

- Packing Pressure: Systematically vary (e.g., up to 500 bar). These parameters directly affect the fidelity of microstructure replication [9].

- Wettability Characterization: Measure the static contact angle of a water droplet on the replicated surfaces using a goniometer. Compare results against flat surfaces and between different processing parameters.

Protocol 2: Altering Sandstone Wettability using Nanocomposites for EOR

This protocol summarizes a lab-scale procedure for investigating wettability alteration in enhanced oil recovery (EOR) [8].

Objective: To assess the efficacy of nanoparticles, biopolymers, and their nanocomposites in changing the wettability of oil-wet sandstone to a water-wet state.

Materials and Equipment:

- Sandstone/Quartz Crystals

- Crude Oil

- Nanoparticles: Fe₃O₄ (Iron Oxide), SiO₂ (Silica)

- Biopolymer: Gelatin

- Nanocomposite: Synthesized Fe₃O₄/Gelatin (Fe/G NC)

- Surfactant: Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)

- Aging Cell

- Contact Angle Goniometer

- Characterization Tools: FT-IR, EDX, FE-SEM, TEM

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Measure the contact angle of a water droplet on a clean, pure quartz surface to establish a baseline (expected ~50°) [8].

- Aging to Create Oil-Wet Surface: Age the quartz samples in crude oil for an extended period (e.g., 22 days) at reservoir conditions to allow adsorption of polar components. Re-measure the contact angle to confirm a shift to an oil-wet state (expected >90°) [8].

- Treatment with Nanofluids/Formulations: Immerse the oil-wet samples in different treatment solutions for a set period (e.g., 11 days):

- Test separate solutions of SiO₂ nanofluid, Fe₃O₄ nanofluid, SDS surfactant, gelatin biopolymer, and Fe/G NC.

- Also test a combined solution of Fe₃O₄ NPs with SDS.

- Post-Treatment Characterization: After aging in the treatment solutions, thoroughly clean the samples and measure the final contact angle. A significant decrease indicates a successful shift towards water-wet conditions.

- Mechanism Analysis: Use characterization techniques to understand the mechanism:

- FE-SEM/TEM: Analyze the morphology and deposition of nanoparticles on the rock surface.

- FT-IR/EDX: Identify chemical changes or new bonds formed on the treated surface.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Wettability and Biomimetic Surface Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorinated Silanes (e.g., Perfluorodecyltrichlorosilane) | Low-surface-energy coating to create intrinsic hydrophobicity/oleophobicity [3]. | Essential for achieving high intrinsic contact angle (θY). Handling may require a fume hood. |

| Metal Oxide Nanoparticles (e.g., SiO₂, Fe₃O₄, TiO₂) | Used to create nanoscale roughness and, in EOR, to generate disjoining pressure for wettability alteration [3] [8]. | Particle size, concentration, and dispersion stability are critical for performance. |

| Polymers (PP, ABS, PA) | Substrates for replication of biomimetic structures. Their intrinsic wettability is amplified by surface texture [9]. | Selection depends on application; PP is inherently hydrophobic, PA is hydrophilic. |

| Gelatin Biopolymer | Acts as a biosurfactant and a modifier for nanoparticles. Contains both hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids, facilitating wettability alteration [8]. | Biodegradable and environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic surfactants. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Synthetic surfactant that reduces interfacial tension, aiding in detachment of oil layers from rock surfaces [8]. | Can be combined with nanoparticles for a synergistic effect. |

Visualization of Wettability Models and Transitions

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between the primary wetting states and the factors influencing transitions between them.

Diagram Title: Wettability States and Transitions

Diagram Description: This flowchart illustrates the pathways between different wetting states. It begins with an ideal solid surface, which is textured to create a rough surface. The wettability of this rough surface then bifurcates based on the intrinsic contact angle (θY) and surface fraction (σ₁): it enters the Wenzel state if the material is hydrophilic or under pressure, and the Cassie-Baxter state if the material is hydrophobic and the solid fraction is low. Unstable conditions can cause a transition from the Cassie-Baxter to the Wenzel state, and both can also exist in intermediate or mixed states.

FAQs: Troubleshooting Biomimetic Surface Experiments

Q1: My biomimetic surface has lost its superhydrophobic properties after mechanical abrasion. What are the primary strategies to improve durability?

A: The loss of superhydrophobicity is often due to the destruction of delicate micro/nanostructures. To enhance durability, consider these strategies based on recent research:

- Self-Similar Structures: Design your surface with a hierarchical structure that has the same chemical functionality at multiple scales. If the topmost nanostructure is damaged, the underlying microstructure can still provide a degree of repellency [3].

- Adhesive Enhancement: Use reinforced adhesives or stronger bonding techniques to improve the adhesion stability between the biomimetic coating and the substrate, preventing delamination [3].

- Self-Healing Surfaces: Incorporate materials that can autonomously repair chemical functionality or, to a lesser extent, physical damage. This can restore hydrophobic properties after minor scratches or chemical exposure [3].

Q2: The air layer (plastron) on my superhydrophobic surface is unstable under water pressure. Which natural prototype offers the best model for compressive stability?

A: The floating fern Salvinia molesta is an excellent model for maintaining a stable air layer under hydrostatic pressure. Its key feature is the unique eggbeater-shaped hairs. Research shows these hairs enhance stability by adapting to pressure through changes in their edge angle and by stabilizing the three-phase (solid-liquid-gas) contact line. Surfaces inspired by this structure can maintain stability at hydrostatic pressures of up to approximately 700 Pa [10].

Q3: Beyond the lotus leaf, what other natural structures are good for creating surfaces that resist oils and other low-surface-tension liquids?

A: Creating superoleophobic surfaces is more challenging than superhydrophobic ones. Two key natural prototypes are:

- Springtails: These soil-dwelling insects have skin with micrometric wrinkles and nanometric doubly reentrant structures, which confer excellent stability and resistance to oils and other liquids [10].

- Fish Scales and Shark Skin: These are naturally oleophilic but achieve underwater superoleophobicity. The trapped air within their microscopic geometric structures changes the underwater wettability, making them excellent models for designing surfaces for oil-water separation [3].

Quantitative Data on Natural Prototypes

The following table summarizes key structural characteristics and performance metrics of prominent natural prototypes.

Table 1: Quantitative Characteristics of Natural Super-Repellent Surfaces

| Natural Prototype | Key Structural Feature | Measured Performance | Primary Durability Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lotus Leaf [11] | Hierarchical micro-papillae and nano-scale wax tubules | Water Contact Angle (WCA): >150°; Self-cleaning | Low surface energy, hierarchical roughness stabilizing the Cassie state |

| Salvinia molesta [10] | Eggbeater-shaped hairs with hydrophilic tips | Can maintain air layer under ~700 Pa hydrostatic pressure; WCA: Nearly spherical | Flexible hairs with hydrophilic tips pin the water surface, stabilizing the air layer |

| Shark Skin [10] | Microscopic groove-like scales (riblets) | Drag reduction in underwater vehicles | Trapped air and surface topography reducing fluid friction |

| Snake Scales [12] | Hexagonal scale patterning | Hexagonal biomimetic weave reduced friction coefficient by up to 41% | Geometric structure for close alignment and retention of lubricating particles |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabricating a Durable, Hexagonal Biomimetic Weave

This protocol is adapted from research on improving the tribological performance of steel surfaces, inspired by snake scales [12].

Objective: To create a biomimetic hexagonal weave on a metal substrate (e.g., Q235 steel) and fill it with solid lubricant to enhance wear resistance.

Materials:

- Substrate (e.g., Q235 steel sheet)

- Laser etching system

- Solid lubricant (e.g., screened refined coal particles, polymers)

- Ultrasonic cleaner

Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean the steel substrate thoroughly with an ultrasonic cleaner to remove surface contaminants and oils.

- Weave Design: Design a hexagonal pattern mimicking snake scales. Key parameters to optimize include:

- Edge Length (L): Target ~700 µm.

- Width (W): Target ~130 µm.

- Depth (D): Target ~160 µm.

- Laser Etching: Use the laser etching system to fabricate the designed hexagonal weave onto the cleaned substrate surface.

- Lubricant Filling: Fill the etched hexagonal weaves with the chosen solid lubricant (e.g., coal particles). Ensure the lubricant is firmly packed into the micro-structures.

- Validation: Test the tribological properties (coefficient of friction, wear volume) using a friction tester and compare the results against a non-textured control surface.

Protocol 2: Testing the Compressive Stability of a Salvinia-Inspired Surface

This protocol is based on experimental measurements of the Salvinia surface [10].

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the stability of the air layer retained by a bio-inspired surface under hydrostatic pressure.

Materials:

- Biomimetic surface sample (with eggbeater-like microstructures)

- Pressure-controlled water immersion tank

- High-speed camera

- Microscope

Methodology:

- Setup: Mount the biomimetic surface sample in the immersion tank. Ensure the surface is horizontal and facing downward or upward as required.

- Initial Observation: Submerge the sample slowly and use the high-speed camera or microscope to observe the formation of a continuous air layer (plastron).

- Pressure Application: Gradually increase the hydrostatic pressure in the tank.

- Data Collection: Record the pressure at which the air layer first shows signs of collapse (e.g., nucleation of water droplets within the structure) and the pressure at which it fully collapses.

- Analysis: Calculate the critical pressure threshold for air layer stability. Compare the performance against the geometric parameters of the microstructures (e.g., hair density, edge angle).

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing and optimizing a durable biomimetic surface, from concept to validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biomimetic Surface Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Application / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Etching System [12] | To precisely create micro-scale patterns and structures on various substrates. | Used to fabricate hexagonal snake-scale weaves on steel or pit arrays on titanium alloy for superhydrophobic surfaces. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [10] | A common polymer for creating flexible, transparent replicas of natural structures. | Used to mimic the flexible properties of Salvinia hairs for drag reduction and stable air layer retention. |

| Fluorinated Silanes (e.g., F-SiO₂) [13] | Chemicals used to create low-surface-energy coatings, essential for liquid repellency. | Applied in composite coatings (e.g., EP@PDMS@F-SiO₂) to achieve superhydrophobicity on titanium alloys. |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) [12] | A statistical technique for modeling and optimizing multiple design parameters. | Used to optimize the geometric parameters (edge length, width, depth) of a biomimetic weave for minimal friction. |

| Shape Memory Alloy (SMA) Springs [13] | Actuators that change shape with temperature, simulating muscle movement. | Integrated into bio-inspired grippers for flapping-wing robots, enabling fast, bidirectional actuation. |

In the pursuit of optimizing biomimetic surface durability, researchers have classified synthetic surface architectures into distinct structural categories: protrusion, linear, pendant, and hierarchical. This taxonomy is not merely descriptive; it provides a critical framework for diagnosing performance issues and selecting appropriate fabrication strategies. These geometries are essential for achieving superamphiphobicity—the ability to repel both water and oil—by manipulating the solid-liquid-gas interface through a combination of surface chemical hydrophobicity and high-roughness micro/nanostructures [3]. The durability of these surfaces is often compromised by the mechanical fragility of their fine features and the instability of the trapped air film. This technical support center addresses the specific experimental challenges encountered when working within this structural taxonomy to enhance the longevity and functional reliability of biomimetic surfaces.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

1. FAQ: Our biomimetic protrusion structures show excellent initial repellency but suffer from rapid mechanical degradation during testing. What are the primary failure modes and how can we mitigate them?

- Problem: Protrusion structures (e.g., micropillars, bumps) are prone to fracture, delamination from the substrate, or permanent bending under external loads, leading to a loss of super-repellency.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Symptom: Fracture at the base of protrusions.

- Cause: High stress concentration at the protrusion-substrate interface and/or use of a brittle material.

- Solution: Redesign the protrusion profile to include a wider base for better load distribution. Consider using polymers or composites with higher fracture toughness instead of pure ceramic or metal coatings.

- Symptom: Permanent bending or collapse of protrusions.

- Cause: Insufficient mechanical strength of the protrusion material or an overly high aspect ratio (height-to-width).

- Solution: Reduce the aspect ratio of the protrusions or incorporate a reinforcing agent (e.g., nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes) into the matrix material to enhance stiffness [3].

- Symptom: Delamination of the entire structured layer.

- Cause: Poor adhesion between the functional coating and the underlying substrate.

- Solution: Implement surface pretreatment processes such as plasma cleaning, chemical etching, or the use of an adhesive primer to enhance interfacial adhesion [14]. Quantitative surface quality measurements are recommended to validate pretreatment efficacy.

- Symptom: Fracture at the base of protrusions.

2. FAQ: We are attempting to create a hierarchical architecture, but our fabrication process is inconsistent and fails to reliably produce features at both micro and nano scales. What methodologies are most robust?

- Problem: Hierarchical structures, which combine two or more length scales (e.g., micro-bumps with nano-hairs), are challenging to fabricate with high fidelity and reproducibility.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Symptom: Poor uniformity in the nano-scale features.

- Cause: Many bottom-up (e.g., self-assembly) methods can be stochastic and difficult to control.

- Solution: Employ a combination of top-down and bottom-up methods. For example, use photolithography or laser etching to create the primary micro-scale structure (e.g., a linear or protrusion pattern) [12], followed by a controlled method like electrolytic deposition [12] or phase separation to generate the secondary nano-scale roughness.

- Symptom: Clogging or merging of nano-features.

- Cause: Over-processing or excessive material deposition during the secondary fabrication step.

- Solution: Carefully optimize the process parameters (e.g., deposition time, etchant concentration, laser power) through a structured Design of Experiments (DoE) approach. Response surface methodology (RSM) has been successfully used to optimize similar biomimetic texture parameters [12].

- Symptom: Poor uniformity in the nano-scale features.

3. FAQ: The Cassie-Baxter state on our pendant-structured surfaces is unstable, leading to an irreversible transition to the Wenzel state (wetting) upon contact with low-surface-tension liquids like oils. How can we improve stability?

- Problem: Pendant structures (or re-entrant structures) are critical for repelling oils, but the composite solid-liquid-air interface can be destabilized.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Symptom: Immediate collapse upon contact with oil.

- Cause: The geometry of the re-entrant curvature may be insufficient to pin the liquid-air meniscus. The "robustness" of the air pocket is geometrically determined.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the pendant structure design using computational modeling (e.g., Surface Evolver) to simulate the liquid-air interface stability. Adjust the overhang angle and the cap-to-post ratio to enhance the energy barrier for the Cassie-to-Wenzel transition.

- Symptom: Gradual transition over time or under slight pressure.

- Cause: The surface chemistry may not be oleophobic enough, or there might be nanoscale defects in the pendant structure.

- Solution: Ensure a uniform, low-surface-energy coating (e.g., fluorinated silanes) is applied. Incorporate a degree of nanoscale roughness (hierarchical design) on the pendant structures themselves to further reinforce the composite interface [3].

- Symptom: Immediate collapse upon contact with oil.

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Optimizing Biomimetic Weave Parameters using Response Surface Methodology

This protocol is adapted from research on improving the tribological performance of metallic surfaces using laser-engraved, hexagonal biomimetic weaves inspired by snake scales [12].

1. Objective: To determine the optimal combination of geometric parameters (edge length, width, depth) for a hexagonal biomimetic weave that minimizes the coefficient of friction and wear.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Substrate: Q235 steel (or other material of interest).

- Laser Etching System: For precise ablation of the weave pattern.

- Solid Lubricant: Refined coal particles or other suitable lubricant filler.

- Tribometer: Reciprocating dry friction tester.

- Profilometer: For 3D contour scanning and wear measurement.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Biomimetic Weave Design. Design a hexagonal pattern (inspired by snake scales) to be engraved on the substrate surface.

- Step 2: Experimental Design. Use a Central Composite Design (CCD) within the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) framework. Define three factors:

- L: Edge Length (µm)

- W: Width (µm)

- D: Depth (µm)

- The response variables are Average Friction Coefficient and Average Wear.

- Step 3: Sample Fabrication. Fabricate multiple samples with parameter combinations as defined by the CCD using the laser etching system.

- Step 4: Filling. Fill the engraved weaves with the solid lubricant (e.g., coal particles).

- Step 5: Tribological Testing. Conduct reciprocating dry friction experiments on all samples.

- Step 6: Data Analysis. Fit the experimental data to a quadratic response surface model. Analyze variance (ANOVA) to identify significant factors and interaction effects. Determine the optimal parameter set that minimizes friction and wear.

4. Expected Outcome: A mathematical model predicting the tribological performance based on weave geometry and a validated set of optimal parameters.

Quantitative Data from Biomimetic Weave Optimization

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from a study that applied RSM to optimize a hexagonal snake-scale-inspired weave [12].

Table 1: Optimal Parameters for Hexagonal Biomimetic Weave from RSM Analysis

| Factor | Parameter | Optimal Value | Influence on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| L | Edge Length | 700 µm | Influences the contact area and structural stability. |

| W | Width | 129.8 µm | Affects the capacity to retain solid lubricant. |

| D | Depth | 159.5 µm | Determines the reservoir volume for wear debris and lubricant. |

| Performance Outcome | Reduction in Friction Coefficient | Up to 41% (vs. smooth surface) | Synergistic effect of optimal geometry and solid lubricant. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biomimetic Surface Durability Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorinated Silanes | Provides low-surface-energy chemistry; crucial for oleophobicity. | Molecular coating on micro/nanostructures to repel oil [3]. |

| Metal Phthalocyanine Precursors | Used to create specific functional films (e.g., ACNT films) with inherent amphiphobic properties [3]. | Served as a foundational material in early superamphiphobic surfaces [3]. |

| Polymer Resins (e.g., for Nanoarchitected Materials) | Base material for creating complex, lightweight, and durable hierarchical architectures via 3D lithography. | Fabrication of impact-resistant nano-lattices that provide mechanical durability [15]. |

| Solid Lubricants (e.g., Refined Coal Particles) | Filler for biomimetic weaves; reduces friction and wear by forming a protective film [12]. | Filling laser-engraved hexagonal weaves on steel to create self-lubricating surfaces [12]. |

| Pyrolytic Carbon | Material for nanoscale struts in architected materials; exhibits unique size-dependent mechanical properties (e.g., rubber-like response) [15]. | Used in nano-architected lattices for dynamic impact absorption studies [15]. |

Structural Relationships & Durability Strategies

The relationship between the four core architectural types and strategies to enhance their durability can be visualized as follows. Hierarchical structures often represent the integration of other types across multiple scales.

Troubleshooting Guide: Mechanical Fragility

This section addresses the failure of biomimetic materials under mechanical stress, a critical barrier to their application in demanding environments such as biomedical implants or protective coatings.

Q1: Why does my 3D-printed biomimetic composite exhibit premature cracking under low impact loads?

A: Premature cracking often originates from inadequate interfacial bonding between the soft and hard phases of your composite, mimicking the "brick-and-mortar" structure of nacre [16].

- Failure Analysis: In a typical "brick-and-mortar" (BM) structure, the hard "bricks" provide strength, while the soft "mortar" dissipates energy through deformation and crack deflection. If the interface is weak, cracks propagate directly through the hard phase instead of being deflected, leading to brittle failure.

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Optimize the Aspect Ratio: Research shows that increasing the aspect ratio (length-to-thickness) of the hard phase significantly enhances energy dissipation. BM structures with an aspect ratio of 10.0 can achieve energy dissipation approximately three times greater than those with an aspect ratio of 1.0 [16].

- Improve Interfacial Design: Focus on enhancing the chemical and mechanical interlocking between the two phases. This can be achieved through surface functionalization of the hard phase or using a softer, more ductile matrix material [17].

Q2: How does the loading rate affect the fracture mode of my dual-phase biomimetic material?

A: The loading rate is a critical, often overlooked, design variable. A material that performs well under quasi-static loads may fail catastrophically under high-speed impact [16].

- Failure Analysis: Under low-velocity impact, nacre-like materials effectively dissipate energy through the "brick-sliding" mechanism. However, at very high velocities, this mechanism becomes less effective, and the material may transition to a more brittle failure mode [16].

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Select Microstructures for Dynamic Loading: For impact resistance, consider microstructures inspired by pangolin scales (triangular) or porcupine quills (hexagonal). Experimental data from dynamic three-point bending tests show these shapes can outperform traditional BM structures under certain high-rate conditions [16].

- Tailor Constituent Materials: Incorporate polymers with viscoelastic properties that become stiffer at higher strain rates, thereby improving dynamic energy absorption [16].

Table 1: Energy Dissipation of Biomimetic Structures Under Dynamic Loading

| Hard Phase Shape | Inspiration Source | Key Energy Dissipation Mechanism | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brick-and-Mortar | Mollusk Nacre | Brick sliding, crack deflection | Effective at low velocities; less so at high impact speeds [16] |

| Triangular | Pangolin Scale | Specific periodic arrangement | Shows promising impact resistance in dynamic tests [16] |

| Hexagonal | Porcupine Quill | Tough outer sheath with porous core | Good failure resistance and mechanical efficiency [16] |

| Circular/Hollow | Beetle Elytra | Hollow sandwich structure | Advantages in lightness and strength [16] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Plastron Loss

The plastron, or the trapped air layer, is fundamental to the function of superhydrophobic surfaces. Its loss leads to the immediate failure of properties like drag reduction and antifouling.

Q1: Why does the superhydrophobicity of my surface diminish after immersion in flowing water?

A: Plastron loss under flow is primarily due to forced convection mass transfer, which dramatically accelerates the dissolution of trapped air compared to quiescent conditions [18].

- Failure Analysis: In still water, air dissolves slowly via diffusion. However, shear flow continuously replenishes the water at the air-water interface, maintaining a high concentration gradient and driving rapid air dissolution. Furthermore, suspended microparticles in the water can collide with the plastron, disrupting the fragile air-water interface and reducing its lifetime by up to ~50% [18].

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Enhance Surface Roughness: Design surfaces with submicron roughness and high aspect ratio features (e.g., re-entrant structures) to stabilize the Cassie-Baxter state and act as larger air reservoirs [3] [19].

- Reduce Flow Shear: In application design, minimize localized high-shear regions to protect the plastron.

- Pre-filter Water: For experimental setups or closed systems, using filtered water to remove suspended particles can significantly extend plastron longevity [18].

Q2: The air layer on my SLIPS is depleting quickly. What could be the cause?

A: Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces (SLIPS) lose functionality when the lubricant layer is depleted, either by evaporation, dissolution, or physical displacement [20].

- Failure Analysis: This is often a failure of the "lockdown" mechanism. The porous substrate must firmly hold the lubricant through capillary forces and chemical affinity. If the pore network is too large or the lubricant viscosity is too low, it can be easily washed away [20].

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Optimize the Porous Matrix: Create a multi-scale porous structure with a high surface area to enhance lubricant retention. A combination of micro-pincushions and nanoparticles has been shown to create a more stable lubricant layer [20].

- Lubricant-Substrate Compatibility: Ensure the lubricant wets the substrate perfectly. Use lubricants with very low surface tension and solubility in the surrounding liquid (e.g., water) [20].

Table 2: Comparison of Plastron-Stabilizing Surface Strategies

| Strategy | Natural Example | Artificial Implementation | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superhydrophobicity (Cassie-Baxter State) | Lotus Leaf, Water Strider Leg | Micro/nano hierarchical structures with low surface energy chemistry [19] | Plastron dissolution under flow and mechanical damage to fragile structures [18] |

| Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces (SLIPS) | Nepenthes Pitcher Plant | Porous or textured solid infused with a lubricating liquid [20] | Lubricant depletion via cloaking, evaporation, or shear flow [20] |

| Anisotropic Superhydrophobicity | Rice Leaf | Parallel microgrooves with nano-sculpturing [19] [20] | Direction-dependent performance; complex fabrication [20] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Chemical Degradation

Chemical degradation attacks the molecular foundation of biomimetic surfaces, leading to irreversible loss of function.

Q1: Why is my superhydrophobic coating losing its water repellency after exposure to UV light and acidic environments?

A: This is a classic case of chemical degradation targeting both the surface microstructure and the low-surface-energy chemistry [3].

- Failure Analysis:

- UV Degradation: Ultraviolet radiation can break the chemical bonds of the low-surface-energy compounds (e.g., fluorinated silanes), making the surface more hydrophilic [3].

- Chemical Attack: Acids or alkalis can corrode the micro/nano-scale features, eroding the physical roughness essential for superhydrophobicity. They can also hydrolyze the chemical modifiers [3].

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Use UV-Stable Materials: Incorporate inorganic rough structures (e.g., SiO₂, TiO₂) or carbon-based coatings that are inherently more resistant to UV radiation [3].

- Design Self-Similar Structures: Create hierarchical structures where the same chemical functionality exists across multiple scales. If the nanostructure is eroded, the microstructure may still retain some hydrophobicity [3].

- Apply Protective Overcoats: Investigate the use of thin, transparent UV-resistant layers that do not significantly alter the surface topography [3].

Q2: The metal-coordinated bonds in my self-healing polymer are not reforming. What factors should I investigate?

A: Metal-coordination complexes (e.g., with Fe³⁺, Zn²⁺) are sensitive to the local chemical environment [17].

- Failure Analysis:

- pH Change: The stability of metal-ligand bonds is highly pH-dependent. A shift in pH can protonate the ligand or precipitate the metal ion, breaking the coordination complex [17].

- Competitive Ligands: Impurities or buffer components in your solution may act as competitive ligands, binding the metal ions more strongly than your polymer and "stealing" them from the network [17].

- Oxidation/Reduction: The metal ion itself may be oxidized or reduced to a state that does not form a stable complex with your ligand [17].

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Control the pH Buffer: Carefully select and maintain a buffer system that is compatible with your metal-ligand pair.

- Purify Reagents: Ensure high-purity solvents and monomers to avoid competitive binding.

- Ligand Design: Synthesize ligands with higher binding constants and selectivity for your specific metal ion.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-situ Monitoring of Plastron Longevity via Total Internal Reflection (TIR)

Objective: To quantitatively measure the stability and lifetime of an air layer (plastron) on a superhydrophobic surface under quiescent and flow conditions [18].

- Sample Preparation: Mount the superhydrophobic sample to be tested at the bottom of a fluid chamber with a transparent window.

- Optical Setup: Direct a laser beam through the chamber wall at an angle greater than the critical angle for total internal reflection at the water/air interface. A CCD camera is positioned to capture the intensity of the reflected light.

- Calibration: Measure and normalize the reflected light intensity against a reference beam to account for laser power fluctuations.

- Data Acquisition:

- Quiescent Condition: Immerse the sample in water and record the TIR signal over time (e.g., 40 hours). The signal will remain high as long as the plastron is intact.

- Flow Condition: Introduce a canonical laminar boundary layer flow (e.g., Reδ = 1400-1800) over the sample and record the TIR signal.

- Data Analysis: The normalized intensity plot versus time reveals the plastron lifetime. A sharp drop indicates a transition from the Cassie-Baxter (non-wetted) state to the Wenzel (wetted) state [18].

Plastron Longevity Measurement Workflow

Protocol 2: Dynamic Three-Point Bending Test for Impact Resistance

Objective: To evaluate the dynamic failure and energy dissipation of biomimetic dual-phase materials under different loading rates [16].

- Specimen Fabrication: Fabricate biomimetic specimens (e.g., BM, triangular, hexagonal) using a multi-material 3D printer to ensure precise control over geometry and constituent materials.

- Test Setup: Install the specimen in a three-point bending fixture on a dynamic mechanical tester (e.g., a split-Hopkinson pressure bar or servohydraulic machine).

- Loading: Apply a controlled impact load at a range of velocities (from quasi-static to high velocity) using a striker.

- Data Collection: Record the complete load-displacement (F-x) curve for each test at a high sampling rate.

- Energy Dissipation Calculation: Calculate the energy dissipation (Ed) up to complete failure by integrating the area under the load-displacement curve, normalized by the cross-sectional area (A₀) [16]: ( Ed = \frac{1}{A0} \int{0}^{d_c} F(x) \,dx )

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biomimetic Durability Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-material 3D Printer | Fabricates complex dual-phase biomimetic structures with controlled geometry and material distribution [16]. | Enables rapid prototyping of intricate microstructures (BM, hexagonal, triangular) for mechanical testing [16]. |

| Poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) | Used as a soft "mortar" phase in composites or as an elastomeric substrate for flexible electronics [16] [20]. | Its modulus and adhesion properties can be tuned; can be used to create SLIPS [20]. |

| Fluorinated Silanes | Provides low surface energy chemistry to create superhydrophobic surfaces [3] [19]. | Susceptible to UV and chemical degradation; requires stabilization strategies [3]. |

| TiO₂/SiO₂ Nanoparticles | Used to construct micro/nano hierarchical roughness for superhydrophobicity or as a photocatalytic material [21] [3]. | Inorganic particles offer enhanced UV and chemical stability compared to organic coatings [21] [3]. |

| Total Internal Reflection (TIR) Setup | Non-invasive, in-situ optical technique for monitoring plastron stability on superhydrophobic surfaces [18]. | Critical for quantifying the longevity of the air layer under different environmental conditions [18]. |

Biomimetic Surface Durability Optimization Path

Building to Last: Fabrication Techniques and Biomedical Applications of Robust Biomimetic Surfaces

Troubleshooting Guides

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D Printing Troubleshooting

Problem: Warping or Corner Lifting

- Issue Details: Edges or corners of the print lift away from the build plate, causing deformation [22].

- Relevance to Biomimetics: Compromises the dimensional accuracy of bio-inspired structures, critical for replicating natural surface geometries.

- Causes and Solutions [22] [23]:

- Cause 1: Poor bed adhesion and material shrinkage (notably with ABS filament).

- Solution: Ensure a level bed; use adhesives like glue stick or specialized products (e.g., WolfBite) on a glass bed; use an enclosure to control the ambient temperature.

- Cause 2: Print cooling too rapidly.

- Solution: Reduce cooling fan speed for the initial layers.

- Cause 3: Build plate temperature is incorrect.

- Solution: Adjust bed temperature according to filament manufacturer's specifications.

- Cause 1: Poor bed adhesion and material shrinkage (notably with ABS filament).

Problem: Under-Extrusion

- Issue Details: Printer does not extrude enough filament, resulting in gaps between extrusion lines, weak layers, or a "stringy" appearance [22] [23].

- Relevance to Biomimetics: Leads to weak infill and poor layer bonding, undermining the mechanical durability of biomimetic prototypes.

- Causes and Solutions [22] [23]:

- Cause 1: Clogged nozzle.

- Solution: Perform a "cold pull" to clear the nozzle or replace it.

- Cause 2: Incorrect filament diameter setting in slicer software.

- Solution: Measure filament diameter and adjust the slicer setting accordingly (e.g., 1.75mm vs. 2.85mm).

- Cause 3: Filament extrusion temperature is too low.

- Solution: Increase nozzle temperature in 5°C increments.

- Cause 1: Clogged nozzle.

Problem: Dimensional Inaccuracy

- Issue Details: Final printed part does not match the designed dimensions [23] [24].

- Relevance to Biomimetics: Critical failure for components requiring tight tolerances, such as those for fluid dynamics or structural studies.

- Causes and Solutions [23] [24]:

- Cause 1: Incorrect printer calibration.

- Solution: Calibrate the printer's X, Y, and Z steps per millimeter (steps/mm).

- Cause 2: Over- or under-extrusion.

- Solution: Calibrate the extruder's E-steps and flow rate.

- Cause 3: Thermal expansion and contraction of filament.

- Solution: Account for material-specific shrinkage in the design phase; use printer profiles tuned for specific materials.

- Cause 1: Incorrect printer calibration.

Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) Troubleshooting

Problem: Residual Stress and Warping

- Issue Details: Internal stresses from rapid heating and cooling cause parts to deform, crack, or warp [25].

- Relevance to Biomimetics: Can distort intricate, high-strength metal biomimetic structures, such as those mimicking bone.

- Causes and Solutions [26] [25]:

- Cause 1: Extreme thermal gradients during printing.

- Solution: Pre-heat the build platform to reduce the temperature difference.

- Cause 2: Improper support structures or part orientation.

- Solution: Use predictive modeling to optimize orientation; design adequate support structures to anchor the part and resist stress.

- Cause 3: Suboptimal scanning strategy.

- Solution: Use an "island" scanning strategy to shorten scan vectors and distribute heat more evenly.

- Cause 1: Extreme thermal gradients during printing.

Problem: Porosity

- Issue Details: Formation of microscopic holes and cavities within the part, leading to reduced density and potential mechanical failure [25].

- Relevance to Biomimetics: Weakens structural components, making them unsuitable for load-bearing applications.

- Causes and Solutions [25]:

- Cause 1: Insufficient or excessive laser energy.

- Solution: Tune machine parameters (laser power, scan speed) to achieve optimal melting.

- Cause 2: Poor quality powder material.

- Solution: Source high-quality, spherical powder from trusted suppliers.

- Cause 3: Inherent process limitations.

- Solution: Apply post-processing techniques like Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) to eliminate pores.

- Cause 1: Insufficient or excessive laser energy.

Electrostatic Flocking Troubleshooting

Problem: Falling Flock (Poor Adhesion)

- Issue Details: Fibers detach from the substrate after the flocking process [27].

- Relevance to Biomimetics: Directly impacts the durability and longevity of fibrillar surfaces designed for bubble-trapping or drag reduction.

- Causes and Solutions [27] [28]:

- Cause 1: Suboptimal adhesive application.

- Solution: Ensure adhesive layer thickness is approximately 10% of the fiber length. Use uniform application methods (e.g., spray, squeegee).

- Cause 2: Improper conductivity of flock fibers.

- Solution: Control ambient humidity (target 65% RH) to ensure fiber conductivity. Measure conductivity with a resistance meter.

- Cause 3: Inadequate substrate pretreatment.

- Solution: Clean and pre-treat surfaces (e.g., corona treatment, plasma, solvent wiping) to increase surface energy and improve adhesion.

- Cause 1: Suboptimal adhesive application.

Problem: Irregular Flock Density or Alignment

- Issue Details: The flocked surface appears patchy, or fibers are not vertically aligned [28].

- Relevance to Biomimetics: Misaligned fibers fail to replicate the consistent microstructures found in biological systems, impairing function.

- Causes and Solutions [28]:

- Cause 1: "Faraday cage" effect in recessed areas.

- Solution: For complex geometries, use electrostatic-pneumatic flocking to support fiber transport into depressions.

- Cause 2: Flock fiber quality.

- Solution: Use fibers with consistent cut length and titier. For many technical applications, a titier of 3.3 dtex is standard.

- Cause 3: Adhesive open time exceeded.

- Solution: Flock immediately after adhesive application before the surface becomes tacky.

- Cause 1: "Faraday cage" effect in recessed areas.

Table 1: Quantitative Troubleshooting Guide for Electrostatic Flocking

| Problem | Key Parameter | Optimal Range | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Falling Flock [27] [28] | Adhesive Layer Thickness | ~10% of fiber length (e.g., 0.2mm for 2mm fiber) | Adjust application method (spray, screen printing) |

| Ambient Humidity [28] | 65% Relative Humidity | Use room humidification/dehumidification systems | |

| Poor Fiber Alignment [28] | Fiber Conductivity | 80-100 Standard Scale Parts | Measure with electrode; adjust humidity or use anti-static treatment |

| Fiber Length & Titier [28] | e.g., 1mm, 3.3 dtex | Select appropriate fiber for the substrate and application |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

3D Printing FAQs

Q: My FDM 3D print is not sticking to the bed. What are the first steps I should take? [22] [23] [29]

A: The most common causes and solutions are:

- Level the Bed: An unlevel bed is the most frequent cause. Re-level your print bed according to your printer's instructions.

- Adjust Nozzle Height: The nozzle should be close enough to the bed so that the first layer is slightly squished.

- Clean the Bed: Oils from your skin can prevent adhesion. Clean the build surface with isopropyl alcohol.

- Use Adhesives: Apply a thin layer of glue stick or hairspray to improve adhesion for certain materials.

- Adjust Temperature: Increase the bed temperature for the first layer.

Q: How can I prevent warping in large DMLS metal parts? [26] [25]

A: To minimize warping in DMLS:

- Optimize Support Structures: Design supports to effectively anchor the part to the build plate and dissipate heat.

- Pre-Heat the Build Platform: This reduces thermal gradients, a primary cause of residual stress.

- Use Predictive Modeling: Software can simulate thermal stresses during printing and suggest optimal part orientation and parameters to mitigate warping.

Q: What causes stringing in FDM prints, and how can I eliminate it? [22] [23]

A: Stringing, or "hairy" prints, is caused by filament oozing from the nozzle during non-print moves.

- Enable Retraction: This is the primary setting. The extruder retracts filament slightly to relieve pressure before moving.

- Tune Retraction Settings: Increase retraction distance and speed in your slicer software.

- Lower Nozzle Temperature: A temperature that is too high can make the filament too runny and prone to oozing.

- Enable Coasting and Wiping: These slicer features can further clean up the nozzle before a travel move.

Electrostatic Flocking FAQs

Q: What are the essential material considerations for achieving a durable flocked surface in a research setting? [28]

A: Durability depends on a systems approach:

- Substrate Preparation: The surface must be clean and have high surface energy (above 42 dyn). Pre-treat with corona, plasma, or primers if necessary.

- Adhesive Selection: The adhesive must be compatible with both the substrate and the flock fiber. It must offer the required flexibility, wash-resistance, or chemical resistance for the final application.

- Flock Fiber Specification: Choose the correct fiber material (e.g., PA, PES), titier (fineness, e.g., 1.7 dtex for soft touch, 3.3 dtex for general use), and cut length for your functional needs.

Q: How do I achieve uniform flocking on a complex, 3D-shaped substrate? [28]

A: Complex geometries with depressions are challenging due to the Faraday cage effect, which disrupts the electric field.

- Use Electrostatic-Pneumatic Flocking: This method combines the electric field with an air stream to propel fibers into recessed areas that a purely electrostatic field cannot reach.

- Multiple Flocking Passes: After a pre-cleaning step, re-flock the part to allow fibers to reach adhesive areas that were initially blocked by loose flock.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabricating a Biomimetic Bubble-Trapping Surface via Electrostatic Flocking

This protocol details the creation of a fibrillar surface inspired by biological air-retaining structures [30].

Workflow Title: Biomimetic Flocking for Bubble Entrapment

Materials and Equipment:

- Substrate: e.g., Polymer sheet, textile.

- Flock Fibers: e.g., Polyamide (PA) or Polyester (PES), cut length 0.5-1.0 mm, titier 1.7-3.3 dtex [28] [30].

- Adhesive: A two-component, water-based or solvent-based polyurethane adhesive suitable for your substrate and intended environment (e.g., underwater) [28].

- Equipment: Electrostatic flocking power supply and applicator (handgun or automated system), adhesive spray gun, drying oven, fume hood.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Substrate Pretreatment:

- Clean the substrate thoroughly with a suitable solvent (e.g., isopropanol) to remove all grease and release agents.

- For low-energy surfaces (e.g., polyolefins), apply a corona, plasma, or primer treatment to ensure a surface tension >42 dyn/cm² for optimal adhesive bonding [28].

- Adhesive Application:

- Prepare the adhesive according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Apply a uniform layer of adhesive. The target thickness of the dried layer should be approximately 10% of the flock fiber length (e.g., a 0.02 mm layer for 0.2 mm fibers). Use a spray gun or squeegee for uniform coverage [28].

- Flocking Process:

- Immediately after adhesive application, place the substrate in the flocking area.

- Set the electrostatic flocking power supply to a high voltage (typically in the tens of kilovolts range).

- Direct the flocking gun towards the substrate, maintaining a consistent distance. The electric field will align and propel the fibers vertically into the adhesive.

- Continue until a dense, uniform fiber layer is achieved. Monitor ambient conditions (21°C, 65% RH ideal) [28].

- Pre-cleaning:

- Gently tap the substrate or use low-pressure compressed air to remove the majority of loose, non-adhered fibers. Collect these for potential reuse [28].

- Drying and Curing:

- Final Cleaning:

- Use compressed air and/or suction cleaning to remove any remaining loose fibers, ensuring a clean, high-quality finish [28].

Protocol: Optimizing DMLS Parameters for Dense, Low-Stress Parts

This protocol outlines the key steps for producing high-integrity metal parts using DMLS, crucial for functional biomimetic components [26] [25].

Workflow Title: DMLS Optimization Workflow

Key Steps and Rationale:

- Support and Orientation:

- Action: In your slicing software, orient the part to minimize the need for supports on critical surfaces. Apply supports for overhangs greater than 0.5 mm and large horizontal surfaces [26].

- Rationale: Proper orientation and support minimize residual stress and warping by providing a thermal pathway to the build plate [25].

- Parameter Selection:

- Action: Select a layer thickness (e.g., 0.02 - 0.08 mm) and optimize laser power and scan speed to achieve full melting of the powder without splattering. Employ an "island" scanning strategy [26] [25].

- Rationale: Correct energy density ensures high part density (>98%), while the island strategy distributes thermal stress, reducing warping [25].

- Build Plate Preparation:

- Action: Pre-heat the build platform according to the material's specifications (higher for SLM, lower for EBM) [25].

- Rationale: Pre-heating reduces the thermal gradient between the molten material and the build plate, a primary driver of residual stress.

- Post-Processing:

- Action: After printing, subject the part to stress relief heat treatment while still on the build plate. For maximum density, use Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) [25].

- Rationale: Stress relief anneals out internal stresses. HIP applies high temperature and isostatic pressure to close internal pores, resulting in near-theoretical density [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biomimetic Surface Manufacturing Research

| Material / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polyamide (PA) Flock Fibers [28] [30] | Creating fibrillar, air-entrapping surfaces for drag reduction and antifouling studies. | Titer: 1.7 dtex (soft) to 3.3 dtex (standard). Length: 0.3 - 1.0 mm. Note: Hydrophobic properties are key for bubble stabilization. |

| Two-Component Polyurethane Adhesive [27] [28] | Bonding flock fibers to the substrate; determines mechanical durability and chemical resistance. | Curing Type: Heat-activated. Flexibility: Must match substrate (flexible for textiles). Key: Layer thickness should be ~10% of fiber length. |

| Metal Powder (e.g., Stainless Steel, Ti-6Al-4V) [25] | Raw material for DMLS printing of high-strength, complex biomimetic structures (e.g., bone scaffolds). | Particle Shape: Spherical for high packing density. Particle Size Distribution: Tight distribution for consistent layer recoating and melting. |

| FDM Filament (e.g., ABS, PLA) [22] [23] [24] | Rapid prototyping of biomimetic geometries for form and function testing. | Diameter: 1.75 mm or 2.85 mm. Shrinkage/Warping: ABS is higher, PLA is lower. Specialty: High-resolution or engineering-grade filaments (e.g., ABS-ESD) available. |

| Surface Pretreatment Primer / Reagent [28] | Modifying substrate surface energy to ensure strong adhesive bonding. | Types: Corona/Plasma treatment, chemical primers, fluorination. Target: Achieve surface tension >42 dyn/cm² for reliable adhesion. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is achieving strong adhesion to low-surface-energy (LSE) polymers like polypropylene (PP) or polyethylene (PE) so challenging?

A1: The primary challenge is poor wettability. LSE polymers have non-polar, chemically inert surfaces with weak intermolecular forces. When a conventional adhesive is applied, its high surface tension prevents it from spreading and making intimate contact with the substrate. This lack of contact restricts the van der Waals forces and other interactions necessary for a strong bond, leading to markedly reduced adhesive strength [31]. Essentially, the adhesive "beads up" rather than spreading evenly.

Q2: How do nanofillers enhance the properties of adhesives for these demanding applications?

A2: Incorporating nanofillers (NFs) like nanosilica, carbon nanotubes, or graphene can tune multiple adhesive properties:

- Improved Wettability: NFs can modify the adhesive's interfacial free energy and work of adhesion, helping it better wet LSE surfaces [32].

- Enhanced Mechanical Properties: They can significantly increase lap shear strength, tensile strength, and toughness by creating a large number of interaction sites with the polymer matrix due to their high surface area [32].

- Multifunctional Benefits: Certain NFs can impart additional properties like electrical or thermal conductivity to the adhesive [32]. Achieving these benefits requires uniform NF dispersion, as agglomerates can act as stress concentrators and weaken the bond [32].

Q3: What are the most effective surface pre-treatment methods for LSE polymers, and how do they work?

A3: Pre-treatments aim to remove contamination and increase the surface energy of the plastic. They can be categorized by their mechanism [33]:

- Physical Modification: Techniques like corona discharge, plasma treatment, and flame treatment use external energy to oxidize the surface, introducing polar functional groups (e.g., carbonyl, hydroxyl) that increase surface energy and improve chemical bonding. Corona and plasma treatments affect only the top ~0.01 micron layer, leaving the bulk properties unchanged [31] [33].

- Chemical Modification: Methods like chromic acid etching alter the surface chemistry and roughness, providing mechanical interlocking sites and increasing reactivity [31].

Q4: Within the context of biomimetic durability, what strategies can make a superamphiphobic surface last longer?

A4: The micro/nano-structures that confer superamphiphobicity are mechanically fragile. Durability can be enhanced by mimicking natural systems through:

- Self-Similar Structures: Designing hierarchical structures where micro-scale features protect the finer nano-scale features from abrasion.

- Adhesive Enhancement: Using reinforced adhesives or matrix materials to improve the adhesion stability of the superamphiphobic coating to the underlying substrate, preventing delamination [3].

- Self-Healing Materials: Incorporating materials that can autonomously repair chemical or physical damage to the surface, restoring liquid-repellent properties after minor abrasion [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Poor Adhesive Wettability and Initial Bond Failure

| Observation | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesive forms droplets, doesn't spread; failure at the adhesive-substrate interface. | Substrate surface energy is too low. [31] [33] | Measure the contact angle of a test liquid on the substrate. A high angle (>90°) confirms low surface energy. | Implement a surface pre-treatment (e.g., plasma, corona) to increase surface energy and remove weak boundary layers [33] [34]. |

| Adhesive surface tension is too high. [33] | Compare the adhesive's surface tension to the substrate's critical surface tension. | Reformulate the adhesive by incorporating flexible chains (e.g., polyethylene glycol) or low surface energy groups to reduce its surface tension [31]. | |

| Surface contamination (oils, release agents). [35] [34] | Use surface analysis techniques (e.g., XPS) or simple solvent wiping to check for contamination. | Establish a controlled cleaning protocol before bonding. Ensure proper handling and storage of substrates [35]. |

Inconsistent Performance of Nanocomposite Adhesives

| Observation | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesive properties are weak or variable; visible agglomerates in the matrix. | Poor dispersion of nanofiller (NF). [32] | Use microscopy (SEM/TEM) to examine the composite for NF agglomerates. | Optimize the dispersion technique (e.g., ultrasonic mixing, calendaring) and use compatibilizers or surface modifiers on the NF [32]. |

| Mechanical properties degrade beyond a certain NF loading. | NF loading is too high, leading to excessive agglomeration and viscosity. [32] | Conduct a titration experiment, testing mechanical properties (lap shear) at different NF loadings. | Identify the optimum filler loading (e.g., 1.5 wt% for nanoalumina in one study) that provides maximum reinforcement without causing defects [32]. |

| Voids or defects in the cured adhesive joint. | Increased viscosity from NFs traps air or prevents proper flow. [32] | Inspect the joint using ultrasonic C-scan or X-ray radiography [36]. | Adjust processing parameters (e.g., pressure, temperature) or incorporate degassing steps during adhesive preparation. |

Loss of Adhesion or Coating Durability Under Stress

| Observation | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coating delaminates under mechanical stress or environmental exposure. | Insufficient energy dissipation in the adhesive layer. [31] | Analyze the failure mode. If it's cohesive, the adhesive itself is failing. | Design adhesives with a balanced viscoelasticity. Interpenetrating Network (IPN) structures, such as polyurethane acrylate/polyacrylate IPNs, can effectively dissipate energy and enhance toughness [31]. |

| Weak interfacial adhesion cannot withstand stress. | Analyze the failure mode. If it's adhesive (at the interface), the bond is the issue. | Ensure adequate surface preparation and consider adhesives that can form chemical bonds with the treated surface. | |

| Superamphiphobic surface loses repellency after abrasion. | Fragile micro/nano-structures are destroyed. [3] | Observe surface morphology under SEM before and after abrasion. | Employ durability enhancement strategies such as designing self-similar structures or using a tougher matrix material to protect the fragile repellent structures [3]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Surface Pre-treatment via Plasma Activation

Objective: To increase the surface energy of a LSE polymer (e.g., PP) to enhance adhesive wettability and bond strength.

Materials:

- Low-surface-energy polymer substrate (e.g., PP sheet)

- Oxygen or air plasma system

- Solvents (isopropanol, acetone)

- Lint-free wipes

- Surface energy evaluation kit or goniometer

Methodology:

- Substrate Cleaning: Clean the polymer substrate with a lint-free wipe soaked in isopropanol to remove gross contamination. Allow to dry.

- Plasma Chamber Setup: Place the cleaned substrate in the plasma chamber. Ensure the chamber is properly sealed.

- Pre-treatment Process:

- Evacuate the chamber to a low base pressure (e.g., 0.1 mbar).

- Introduce the process gas (e.g., oxygen) at a controlled flow rate.

- Ignite the plasma and treat the substrate for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-120 seconds) at a specific power (e.g., 100 W). Note: Overtreatment can damage the surface. [35]

- Post-treatment Handling: Remove the substrate from the chamber. Bonding should be performed immediately or within a specified time frame after treatment, as the activated surface can undergo hydrophobic recovery over time.

Validation: Measure the water contact angle before and after treatment. A significant decrease in the contact angle confirms an increase in surface energy and improved wettability [33].

Protocol: Fabricating a Nanosilica-Reinforced Epoxy Adhesive

Objective: To synthesize an epoxy nanocomposite adhesive with enhanced mechanical and adhesion properties.

Materials:

- Epoxy resin (e.g., DGEBA)

- Hardener (e.g., polyamine)

- Fumed nanosilica (hydrophobic or hydrophilic, depending on compatibility)

- Solvent (e.g., acetone) for facilitated mixing

- High-shear mechanical stirrer and ultrasonic bath with probe sonicator

Methodology:

- Dispersion of Nanofiller:

- Calculate the required amount of nanosilica for the target loading (e.g., 1-5 wt% of resin).

- Add the nanosilica to a portion of the epoxy resin or a suitable solvent. Mix using high-shear mechanical stirring for 10 minutes.

- Subsequently, subject the mixture to probe ultrasonication on an ice bath (to prevent overheating) for a set time (e.g., 15-30 minutes at 200-400 W) to break down agglomerates [32].

- Composite Formulation:

- Combine the nanosilica dispersion with the remaining epoxy resin. If a solvent was used, remove it by heating under vacuum with constant stirring.

- Add the stoichiometric amount of hardener to the mixture and stir thoroughly but gently to avoid entrapping air.

- Degassing:

- Place the adhesive mixture in a vacuum desiccator until air bubbles cease to emerge.

- Curing:

- Apply the adhesive to the prepared substrates and cure according to the epoxy system's specifications (e.g., 24h at room temperature or a heated cycle).

Validation: Perform lap shear strength tests (ASTM D1002) on bonded joints and compare the failure load and mode against a control adhesive without nanosilica. An increase in strength and a shift towards cohesive failure indicate successful reinforcement [32].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Comparisons

Table 1: Adhesive Performance on Low-Surface-Energy Substrates

This table summarizes quantitative data for a developed Polyurethane Acrylate/Polyacrylate Interpenetrating Network (PSA-PUA) pressure-sensitive adhesive, demonstrating the effect of composition on key performance metrics [31].

| Adhesive Formulation | Polyurethane Acrylate (PUA) Content | Peel Strength (N/cm) | Loop Tack (N/cm) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSA-PUA0 | 0 wt% | Low | Low | Baseline polyacrylate PSA with poor performance on LSE substrates. |

| PSA-PUA10 | 10 wt% | Moderate | Moderate | Improved wettability and adhesion. |

| PSA-PUA20 | 20 wt% | High | High | Optimal composition. Remarkable adhesive qualities due to balanced properties. |

| PSA-PUA30 | 30 wt% | Decreased | Decreased | Potential over-modification; viscoelastic properties may have been negatively altered. |

Table 2: Impact of Nanofiller Addition on Adhesive Properties

This table generalizes the effects of incorporating various nanofillers, based on a review of the literature [32].

| Nanofiller Type | Typical Optimal Loading | Key Property Enhancements | Challenges & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoalumina (Al₂O₃) | ~1.5 wt% | ↑ Lap shear strength by ~40%↑ Tensile strength by ~60% | Effective at low loadings; dispersion is critical. |

| Nanosilica (SiO₂) | 1-5 wt% | ↑ Toughness and modulus↑ Thermal stability | Surface modification often needed for compatibility. |

| Carbon Nanotubes | 0.5-2 wt% | ↑ Electrical/thermal conductivity↑ Strength | Prone to agglomeration; requires strong dispersion methods. |

| Graphene | 0.1-1 wt% | ↑ Barrier properties↑ Mechanical strength | High aspect ratio; functionalization improves dispersion. |

Experimental Workflow and Adhesion Mechanisms

Workflow for Adhesive Optimization

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for developing and optimizing an adhesive for low-surface-energy polymers, integrating material selection, modification, and validation.

Mechanisms of Adhesion Enhancement

This diagram contrasts the failure mechanisms of unmodified interfaces with the reinforcement strategies provided by nanocomposites and interpenetrating networks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Adhesive Enhancement Research

| Item | Function / Role in Research | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Surface-Energy Polymers | The target substrate for adhesion studies. | Polypropylene (PP), Polyethylene (PE), Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) [31]. |

| Base Adhesive Polymers | The primary matrix for the adhesive. | Acrylics (e.g., 2-ethylhexyl acrylate, acrylic acid), Epoxies, Polyurethane Acrylates (PUA) [31] [32]. |

| Nanofillers (NFs) | Reinforce the adhesive matrix, improve wettability, and add functional properties. | Nanoalumina (Al₂O₃), Nanosilica (SiO₂), Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene, Nanoclays [32]. |

| Surface Pre-treatment Equipment | Modifies the substrate surface to increase energy and improve bonding. | Plasma Treatment Systems, Corona Discharge Treaters, Flame Treatment Equipment [31] [33]. |

| Dispersion Equipment | Achieves uniform distribution of nanofillers within the adhesive matrix. | Ultrasonic Probe Sonicators, High-Shear Mechanical Mixers, Calendaring Systems [32]. |

| Characterization Tools | Measures surface properties, adhesion strength, and material morphology. | Goniometer (Contact Angle), Lap Shear Tester, Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) [36] [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: My 3D-printed hierarchical honeycomb structure exhibits premature buckling during compression testing, rather than the desired stable crushing. What could be the cause?

Several factors can lead to this issue. Please consult the following table for potential causes and solutions.

| Problem Cause | Description | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Cell-Wall Thickness | Relative density is too low, leading to elastic buckling instead of plastic deformation. | Increase the cell-wall thickness to raise the relative density. For 2nd order hierarchical honeycombs, ensure the ratio of sub-cell to parent-cell wall thickness is optimized [37]. |

| Sub-optimal Hierarchical Ratio | The size ratio between hierarchical levels causes stress concentration at the sub-cell junctions. | Redesign the self-similar structure. For vertex-based hierarchy, ensure the ratio of the sub-hexagon cell wall length (l) to the base hexagon cell wall length (L) is carefully selected (e.g., l/L = 0.2-0.45) [38]. |