Optimizing Nanoparticle Drug Delivery: Bridging the Translational Gap from Bench to Bedside

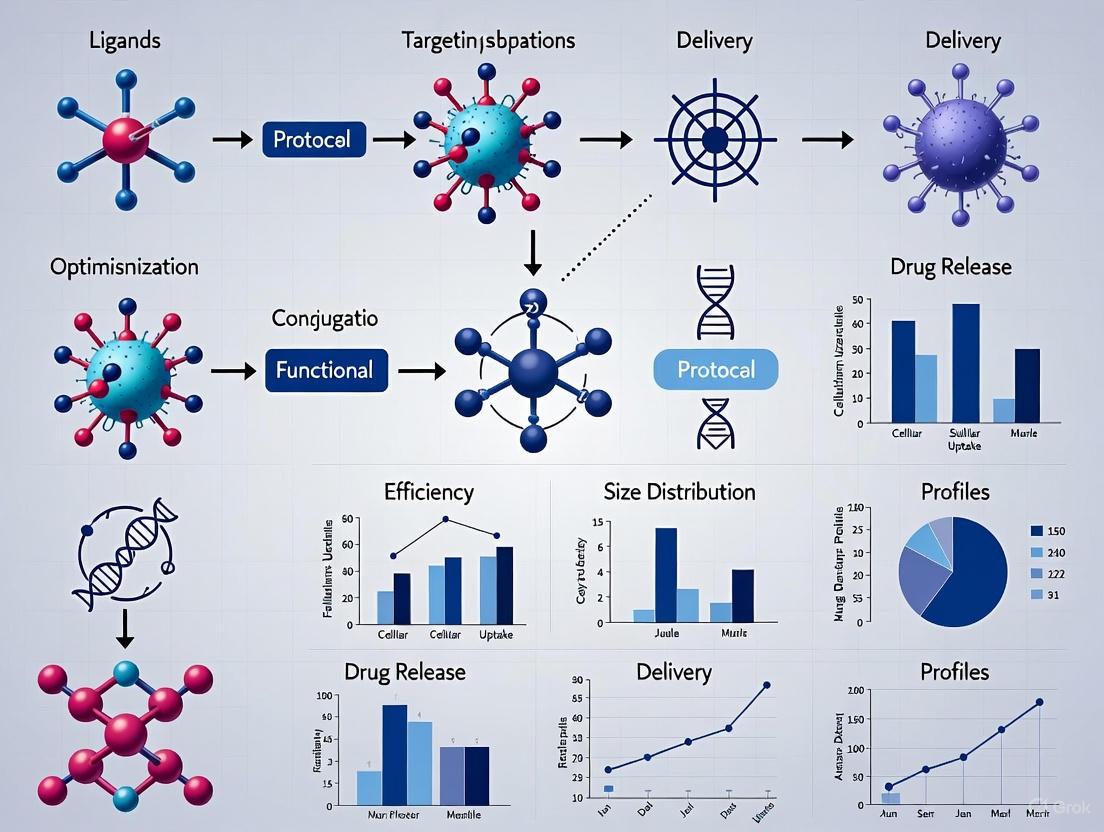

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing nanoparticle-based drug delivery protocols.

Optimizing Nanoparticle Drug Delivery: Bridging the Translational Gap from Bench to Bedside

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing nanoparticle-based drug delivery protocols. It addresses the critical translational gap in nanomedicine, where despite extensive preclinical research, fewer than 0.1% of nanomedicines achieve clinical approval. The content explores foundational principles of nanoparticle design, advanced formulation methodologies including lipid and polymer-based platforms, and innovative troubleshooting strategies leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning. It further covers critical validation and comparative analysis techniques essential for ensuring safety, efficacy, and manufacturability. By integrating recent advances in computational modeling, AI-driven design, and novel formulation technologies, this resource aims to equip scientists with practical strategies to enhance nanoparticle delivery efficiency, overcome biological barriers, and accelerate the development of clinically viable nanotherapeutics.

Understanding the Nanomedicine Landscape and Translational Challenges

The field of nanomedicine represents a revolutionary approach to drug delivery, offering unprecedented potential for enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity. Nanoparticle-based systems enable precise drug targeting, improved solubility of hydrophobic compounds, and controlled release profiles that are unattainable with conventional formulations. Despite extensive research investment and promising preclinical results, a significant translational gap persists, with only a minute fraction of laboratory developments progressing to clinical application. Quantitative analysis reveals that while over 100,000 scientific articles on nanomedicines were published in the past decade, only approximately 90 nanomedicine products had obtained global marketing approval by 2023, representing less than 0.1% of research output reaching patients [1]. This discrepancy highlights fundamental challenges in translating nanomedical innovations from laboratory research to clinically viable therapies.

The translational gap in nanomedicine stems from interconnected scientific, manufacturing, and regulatory barriers. Scientifically, the over-reliance on enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effects observed in murine models has proven problematic, as this phenomenon demonstrates significant heterogeneity and limited occurrence in human tumors [1]. From a manufacturing perspective, complexities in scaling up production while maintaining batch-to-batch consistency present substantial hurdles [2]. Regulatory challenges further complicate translation, as evolving guidelines from the FDA and EMA struggle to keep pace with the unique characteristics of nanopharmaceuticals [3]. This application note provides a comprehensive analysis of these barriers and offers detailed protocols to bridge the translational gap through optimized nanoparticle design, characterization, and manufacturing processes.

Quantitative Analysis of the Translational Landscape

Clinical Translation Metrics for Nanomedicines

Table 1: Clinical Translation Metrics in Nanomedicine (2000-2025)

| Metric | Value | Contextual Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Global nanomedicine approvals | ~90 products | As of 2023, from >100,000 publications [1] |

| Estimated clinical translation rate | <0.1% | Percentage of research output reaching clinic [1] |

| Dominant approved platform types | Liposomes, nanocrystals, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) | >60% market share [1] |

| Nanomedicines in clinical trials | ~500 candidates | As of 2023 [1] |

| Overall drug development success rate | 7-20% | Varies by study methodology [4] |

| Global nanomedicine market projection | >US $570 billion | By 2032 [1] |

The disproportionately low conversion rate from preclinical research to clinical approval reflects fundamental disconnect between laboratory innovation and clinical practicality. The nanomedicine portfolio remains dominated by first-generation platforms, particularly liposomes, with more complex nanocarriers struggling to achieve regulatory endorsement [1]. This translational bottleneck is exacerbated by the inherent challenges of drug development, where costs can exceed $2.5 billion per approved compound, with nanomedicines facing additional complexities in quality control, manufacturing, and regulatory standardization [1].

Analysis of Success and Failure Cases

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Approved and Failed Nanomedicines

| Nanomedicine | Platform Type | Indication | Outcome | Key Limiting Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxil/Caelyx | PEGylated liposome | Ovarian cancer, breast cancer | Approved | Reduced cardiotoxicity vs. free doxorubicin; limited by hand-foot syndrome [1] |

| Abraxane | Albumin-bound paclitaxel | Breast cancer, pancreatic cancer | Approved | Improved drug solubility; relies on EPR effect [1] |

| COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) | COVID-19 prophylaxis | Approved | Efficient nucleic acid delivery; proven scalability [5] |

| BIND-014 | Targeted docetaxel nanoparticles | Prostate cancer, lung cancer | Phase II failure (terminated) | Failed primary efficacy endpoints despite promising early activity [1] |

The failure of advanced platforms like BIND-014 despite robust preclinical evidence underscores the critical gap between molecular targeting demonstrated in animal models and actual impact on human clinical outcomes [1]. This case illustrates that sophisticated targeting mechanisms alone are insufficient without addressing the complexities of intratumor distribution and patient selection biomarkers.

Root Causes of the Translational Gap

Biological Challenges

The biological challenges in nanomedicine translation primarily center on the limited predictive value of animal models for human pathophysiology. The EPR effect, while robust and reproducible in murine tumor models, demonstrates significant heterogeneity in human patients due to factors including vascular heterogeneity, elevated interstitial pressure, and diverse non-EPR entry routes [1]. This discrepancy frequently results in overestimated efficacy predictions during preclinical development. Additionally, nanomedicine behavior is further complicated by complex interactions with biological barriers that impact pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, causing efficacy signals observed in animals to diminish in clinical trials [1].

Nanoparticle transport faces additional challenges in specific therapeutic contexts, particularly neurological disorders. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) represents a formidable obstacle, with its tight junctions and efflux transporters severely restricting drug delivery to the brain [6]. While BBB integrity may be partially compromised in late-stage Alzheimer's disease, early-stage interventions require sophisticated targeting strategies to achieve therapeutic drug levels in the brain [6]. Similar challenges exist in glioblastoma treatment, where the BBB and tumor heterogeneity limit effective drug accumulation despite the urgent need for improved therapies [7].

Manufacturing and Scalability Hurdles

The transition from laboratory-scale synthesis to industrial production represents a critical bottleneck in nanomedicine development. Polymeric nanoparticles, exemplified by PLGA systems, demonstrate exceptional versatility in controlled release applications but present significant challenges in batch-to-batch reproducibility during scale-up [1] [2]. Conventional small-scale production methods are characterized by substantial variability, complicating the maintenance of critical quality attributes (CQAs) when increasing production volume [2]. This manufacturing inconsistency directly impacts nanoparticle performance, including drug release profiles, stability, and in vivo behavior.

The complexity of nanomedicine manufacturing extends beyond particle synthesis to comprehensive quality control systems. Critical process parameters (CPPs) and critical material attributes (CMAs) must be rigorously controlled throughout scale-up to ensure final product quality [8]. Advanced manufacturing technologies, including microfluidics and supercritical fluid processes, offer improved reproducibility but require specialized expertise and infrastructure not routinely available in conventional pharmaceutical production facilities [8].

Regulatory and Characterization Challenges

The regulatory landscape for nanomedicines remains complex and evolving, with harmonized standards still under development. Regulatory agencies including the FDA and EMA provide guidance on nanopharmaceuticals, but the absence of universally accepted characterization standards complicates the approval pathway [3]. Key challenges include standardized assessment of nanotoxicology, immunogenicity, and long-term biocompatibility, particularly for novel nanomaterial platforms without established regulatory precedent.

Comprehensive characterization presents additional hurdles, as nanomedicines require multifaceted analysis of physicochemical properties, surface characteristics, drug release kinetics, and stability under physiological conditions. The dynamic nature of nanoparticles in biological environments further complicates characterization, as properties may change significantly upon interaction with plasma proteins and cellular components [1]. These challenges collectively contribute to the protracted development timelines and high attrition rates observed in nanomedicine translation.

Experimental Protocols for Translation-Ready Nanomedicine Development

Protocol: Computational Modeling for Lipid Nanoparticle Optimization

Objective: Employ multiscale computational modeling to predict LNP behavior and optimize formulation prior to experimental validation, reducing development cycles and resource utilization.

Materials:

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster (minimum 64 cores, 256 GB RAM)

- Software: GROMACS, CHARMM, or AMBER for molecular dynamics; Martini Coarse-Grained force field; Python with scikit-learn for machine learning analysis

- Experimental validation: Microfluidic mixer for LNP formation; dynamic light scattering for size and PDI; transfection efficiency assays

Procedure:

System Preparation (Week 1)

- Obtain or generate molecular structures of ionizable lipids, helper lipids, cholesterol, and PEG-lipids

- Parameterize novel lipids using quantum chemistry calculations (DFT) when necessary

- Build initial simulation boxes with varying lipid ratios and protonation states

Molecular Dynamics Simulation (Weeks 2-4)

- Run all-atom MD simulations (50-100 ns) to study lipid-RNA interactions and internal structure

- Perform coarse-grained MD simulations (1-10 μs) to capture self-assembly过程和endosomal escape mechanisms

- Implement constant pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) to model environment-dependent protonation states [5]

- Apply enhanced sampling techniques (metadynamics, umbrella sampling) for rare events like endosomal fusion

Data Analysis and Machine Learning (Week 5)

- Extract key parameters: membrane curvature, lipid diffusion coefficients, nucleic acid encapsulation efficiency

- Train random forest or neural network models using experimental data and simulation descriptors

- Identify critical formulation parameters predicting encapsulation and transfection efficiency

Experimental Validation (Weeks 6-8)

- Prepare LNP formulations with compositions predicted by computational models

- Characterize physicochemical properties (size, PDI, encapsulation efficiency)

- Evaluate in vitro performance using relevant cell lines

Troubleshooting:

- If simulations show poor agreement with experimental data, verify force field parameters and consider longer equilibration times

- For unstable simulations, increase constraint algorithms and reduce timestep

- If ML models show poor predictive power, expand feature set and increase training data diversity

Protocol: Advanced In Vitro BBB Penetration Assessment

Objective: Establish a predictive in vitro blood-brain barrier model to evaluate nanoparticle penetration capabilities for neurological applications.

Materials:

- Cell lines: Primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs), astrocytes, pericytes

- Transwell systems: 12-well plate, 3.0μm pore size, 1.12 cm² growth area

- Nanoparticles: Fluorescently labeled nanoparticles with various surface modifications

- Characterization equipment: TEER measurement system, confocal microscopy, HPLC-MS

Procedure:

BBB Model Establishment (Days 1-7)

- Culture HBMECs on collagen-coated Transwell apical chambers

- Seed astrocytes and pericytes in basolateral chambers to establish tri-culture system

- Monitor transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) daily until >150 Ω·cm²

- Validate barrier integrity with sodium fluorescein permeability (Papp < 1.0 × 10⁻⁶ cm/s)

Transport Studies (Day 8)

- Apply nanoparticles (100 μg/mL) in serum-free medium to apical chamber

- Collect basolateral samples at 0, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes

- Analyze nanoparticle concentration using appropriate methods (fluorescence, HPLC)

- Calculate apparent permeability coefficients (Papp)

Mechanistic Investigations (Day 9)

- Pre-treat with various inhibitors: chlorpromazine (clathrin-mediated endocytosis), amiloride (macropinocytosis), nystatin (caveolae-mediated endocytosis)

- Evaluate energy dependence by performing transport at 4°C

- Assess specific receptor-mediated pathways using receptor-blocking antibodies

Intracellular Trafficking (Day 10)

- Fix cells at designated time points

- Immunostain for endosomal/lysosomal markers (EEA1, LAMP1)

- Image using confocal microscopy with z-stack acquisition

- Analyze colocalization coefficients using ImageJ software

Data Analysis:

- Calculate Papp = (dQ/dt) × (1/(A × C₀)), where dQ/dt is transport rate, A is membrane area, C₀ is initial concentration

- Compare transport efficiency across different nanoparticle formulations

- Determine primary transport mechanisms through inhibitor studies

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for assessing nanoparticle transport across in vitro blood-brain barrier models.

Protocol: Quality-by-Design (QbD) Approach for Nanoparticle Manufacturing

Objective: Implement systematic QbD methodology to identify critical process parameters and establish design space for reproducible nanomedicine manufacturing.

Materials:

- Equipment: Microfluidic mixer (e.g., staggered herringbone, multi-inlet vortex mixers)

- Analytical instruments: DLS, NTA, HPLC, DSC, XPS

- QbD software: MODDE, Design-Expert, or JMP for experimental design and analysis

Procedure:

Define Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) (Week 1)

- Identify critical quality attributes (CQAs): particle size, PDI, encapsulation efficiency, drug loading, zeta potential, release profile

- Establish target ranges for each CQA based on therapeutic requirements

- Document QTPP in structured format with justification for each parameter

Risk Assessment (Week 2)

- Conduct failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) for materials and process parameters

- Identify potential critical material attributes (CMAs) and critical process parameters (CPPs)

- Prioritize high-risk factors for experimental evaluation

Experimental Design (DoE) (Week 3)

- Design screening experiments (fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman) to identify significant factors

- Develop response surface methodology (RSM) designs (central composite or Box-Behnken) for optimization

- Define factor ranges based on preliminary experiments and risk assessment

Process Optimization (Weeks 4-6)

- Execute DoE experiments using automated microfluidic systems

- Characterize CQAs for each experimental run

- Build mathematical models relating CPPs to CQAs

- Establish design space with proven acceptable ranges for CPPs

Control Strategy (Week 7)

- Define normal operating ranges and proven acceptable ranges for CPPs

- Implement process analytical technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring

- Establish control strategy for raw materials and in-process testing

Data Analysis:

- Perform multiple linear regression to build predictive models

- Calculate model adequacy metrics (R², Q², model validity)

- Generate contour plots to visualize design space

- Validate models with confirmation experiments

Visualization of Key Biological Pathways and Workflows

Nanoparticle Transport Across the Blood-Brain Barrier

Diagram 2: Primary mechanisms for nanoparticle transport across the blood-brain barrier.

Quality-by-Design Implementation Workflow

Diagram 3: Systematic Quality-by-Design workflow for nanomedicine development.

Research Reagent Solutions for Translational Nanomedicine

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nanoparticle Translation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | LNP core component for nucleic acid encapsulation | pKa optimization (6.2-6.5), biodegradability, fusogenicity | DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102, ALC-0315 [5] |

| PEG-Lipids | Surface stabilization, reduction of protein adsorption | Chain length, concentration-dependent immunogenicity | DMG-PEG2000, DSG-PEG2000 [1] |

| Targeting Ligands | Active targeting to specific cells/tissues | Conjugation chemistry, density, orientation, binding affinity | Transferrin, folate, RGD peptides, monoclonal antibodies [6] |

| Biodegradable Polymers | Controlled release, structural matrix | Degradation rate, mechanical properties, byproducts | PLGA, PLA, chitosan, poly(β-amino esters) [1] [7] |

| BBB Models | Assessment of brain penetration | TEER values, transporter expression, paracellular permeability | Primary HBMECs, iPSC-derived endothelial cells, triple-culture systems [6] |

| Microfluidic Devices | Reproducible nanoparticle production | Mixing efficiency, Reynolds number, throughput | Staggered herringbone mixer, multi-inlet vortex mixer [8] |

| Characterization Instruments | Comprehensive nanoparticle analysis | Resolution, sensitivity, standardization | DLS, NTA, HPLC, TEM, SPR [1] |

Bridging the translational gap in nanomedicine requires a fundamental shift from isolated nanoparticle optimization to integrated formulation strategies that address biological, manufacturing, and regulatory challenges simultaneously. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide a framework for developing translation-ready nanomedicines with enhanced potential for clinical success. Key advancements in computational modeling, predictive in vitro systems, and QbD manufacturing represent critical enablers for accelerating nanomedicine translation.

Future progress will depend on continued collaboration between computational scientists, formulation experts, biologists, and clinical researchers to establish robust predictive models and standardized characterization approaches. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning throughout the development pipeline offers particular promise for identifying optimal formulation parameters and predicting in vivo performance. Additionally, increased emphasis on patient stratification biomarkers and disease-specific targeting strategies will be essential for demonstrating clear clinical benefit in well-defined patient populations. By adopting these comprehensive approaches, the nanomedicine field can systematically address the translational gap and fulfill its potential to revolutionize therapeutic interventions for complex diseases.

The selection of an appropriate nanoparticle platform is a critical determinant of success in drug development, impacting therapeutic efficacy, stability, and clinical translatability. This application note provides a systematic comparison of three core nanoparticle platforms: lipid-based, polymeric, and lipid-polymer hybrid systems. Within the context of optimizing nanoparticle-based drug delivery protocols, we present standardized experimental methodologies, quantitative performance data, and characterization workflows to guide researchers in selecting and implementing these technologies. By integrating detailed protocols with comparative analysis of pharmaceutical attributes, this document serves as a practical framework for rational nanocarrier design and development in preclinical research.

Nanoparticle-based delivery systems have revolutionized pharmaceutical development by addressing fundamental challenges associated with conventional drug administration, including poor solubility, limited bioavailability, and off-target toxicity [1]. Among the diverse array of nanocarriers, three platforms have emerged as particularly significant for therapeutic delivery: lipid nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, and lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles.

Lipid-based systems, notably liposomes and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), offer superior biocompatibility and have gained validation through clinical success in mRNA vaccine delivery [9] [1]. Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) provide exceptional structural stability and controlled release profiles through their tunable polymer matrices [10] [11]. Hybrid systems strategically combine material classes to leverage the advantages of both components while mitigating their individual limitations [12] [13].

The global nanoparticle technology market, valued at an estimated USD 10.8 billion in 2025 and projected to reach USD 18.4 billion by 2035, reflects the growing importance of these platforms across pharmaceutical applications [14]. This document establishes standardized protocols and comparative metrics to support researchers in navigating the selection, formulation, and characterization of these core platforms within integrated drug development workflows.

Comparative Analysis of Nanoparticle Platforms

A systematic understanding of the fundamental attributes of each nanoparticle platform enables informed selection based on therapeutic requirements. The following analysis compares the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of lipid, polymeric, and hybrid systems.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Core Nanoparticle Platforms

| Parameter | Lipid Nanoparticles | Polymeric Nanoparticles | Lipid-Polymer Hybrids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Composition | Ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, PEG-lipids [9] | PLGA, PLA, chitosan, PEG-b-PLA [10] [13] | Polymer core with lipid shell [12] [13] |

| Structural Model | Amorphous or non-bilayer structure [9] | Solid polymer matrix [11] | Core-shell architecture [13] |

| Key Advantage | Excellent biocompatibility; Efficient nucleic acid delivery [9] [1] | Superior stability; Controlled release kinetics [10] [13] | Combines stability of polymers with biocompatibility of lipids [12] |

| Primary Limitation | Poor structural stability; Drug leakage [12] [13] | Potential biocompatibility concerns; Use of toxic solvents [10] [13] | Complex fabrication process [13] |

Table 2: Pharmaceutical Performance and Application Scope

| Parameter | Lipid Nanoparticles | Polymeric Nanoparticles | Lipid-Polymer Hybrids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Loading | Moderate for hydrophobic drugs; Poor for hydrophilic macromolecules [13] | High for hydrophobic drugs [13] | High for both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs [12] |

| Encapsulation Efficiency | Low for macromolecular peptides/proteins [12] | High for hydrophobic drugs [13] | High for peptides and proteins [12] |

| Release Profile | Burst release potential [13] | Sustained, controlled release [10] [13] | Controlled release with reduced burst effect [12] |

| Ideal Cargo | Nucleic acids (siRNA, mRNA), small molecules [9] | Small molecules, hydrophobic drugs [11] | Peptides, proteins, sensitive biologics [12] [13] |

The selection of a nanoparticle platform represents a critical risk-benefit analysis. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) provide a clinically validated platform for nucleic acid delivery but face challenges with structural stability and encapsulation of macromolecules [9] [13]. Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) offer superior control over drug release profiles but raise potential biocompatibility concerns and often require organic solvents in preparation [10] [13]. Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNs) represent an advanced solution that combines the structural stability of polymers with the biocompatibility and surface functionalities of lipids, making them particularly suitable for delivering sensitive biomolecules like peptides and proteins [12] [13].

Experimental Protocols

Standardized preparation methods are essential for generating reproducible, high-quality nanoparticles with predetermined characteristics. Below are detailed protocols for the fabrication of each platform.

Lipid Nanoparticle Preparation via Microfluidic Mixing

This protocol describes the preparation of LNPs using microfluidic mixing, a method that ensures excellent control over particle size and uniformity [9] [15].

Materials:

- Lipid Mixture: Ionizable lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA), phospholipid (e.g., DSPC), cholesterol, PEG-lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG 2000) [9]

- Aqueous Phase: Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 7.4) or citrate buffer (pH 4.0)

- Therapeutic Payload: mRNA, siRNA, or small molecule drug

- Equipment: Microfluidic mixer (e.g., NanoAssemblr, Precigenome system), syringe pumps, thermomixer [15]

Procedure:

- Lipid Phase Preparation: Dissolve ionizable lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid in ethanol at a defined molar ratio (e.g., 50:10:38.5:1.5). Total lipid concentration should be 5-10 mM.

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Dissolve the therapeutic payload (e.g., mRNA) in an acidified aqueous buffer (pH 4.0) at a concentration of 0.1-0.2 mg/mL.

- Microfluidic Mixing:

- Load the lipid and aqueous phases into separate syringes.

- Set the total flow rate (TFR) to 10-15 mL/min and the flow rate ratio (FRR, aqueous:organic) to 3:1.

- Initiate simultaneous pumping through the microfluidic mixer.

- Collect the resulting LNP suspension in a sterile vessel.

- Buffer Exchange and Purification:

- Dialyze the formed LNPs against PBS (pH 7.4) for 2 hours at 4°C to remove ethanol.

- Alternatively, use tangential flow filtration (TFF) to concentrate and diafilter the LNPs.

- Sterile Filtration: Filter the final formulation through a 0.22 µm sterile filter.

- Storage: Store LNPs in single-use bags at 2-8°C for short-term storage [15].

Critical Parameters:

- Lipid composition and molar ratios directly impact encapsulation efficiency and endosomal escape [9].

- Flow rates during microfluidic mixing determine particle size and polydispersity [13].

Polymeric Nanoparticle Preparation via Nanoprecipitation

This protocol describes the formation of PNPs using nanoprecipitation, a simple and versatile method ideal for encapsulating hydrophobic drugs [11] [2].

Materials:

- Polymer: PLGA, PLA, or PEG-b-PLA

- Organic Solvent: Acetone or acetonitrile

- Aqueous Phase: Deionized water with or without stabilizer (e.g., Poloxamer 188)

- Drug: Hydrophobic active compound (e.g., paclitaxel)

Procedure:

- Organic Phase Preparation: Dissolve the polymer and drug in a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., acetone) at a typical polymer concentration of 5-10 mg/mL.

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Fill a beaker with deionized water (typically 10-20 mL) containing a stabilizer (e.g., 0.1-0.5% w/v Poloxamer 188).

- Nanoprecipitation:

- Under moderate magnetic stirring (500-700 rpm), rapidly inject the organic phase (1-2 mL) into the aqueous phase using a syringe.

- Continue stirring for 2-4 hours to allow complete solvent evaporation.

- Concentration and Purification:

- Concentrate the PNP suspension using rotary evaporation or ultrafiltration.

- Purify by centrifugation or dialysis to remove free drug and solvent residues.

- Storage: Store the final PNP suspension at 4°C or lyophilize for long-term storage.

Critical Parameters:

- Polymer molecular weight and drug-to-polymer ratio control drug loading and release kinetics [10].

- The injection speed and stirring rate significantly influence particle size distribution [2].

Lipid-Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticle Preparation

This two-step protocol forms LPHNs with a polymeric core and lipid shell, combining the advantages of both systems for peptide/protein delivery [12] [13].

Materials:

- Polymer: PLGA or PEG-b-PLA

- Lipids: Lecithin, cholesterol, DSPE-PEG

- Aqueous Phase: Deionized water or PBS

- Drug: Peptide or protein (e.g., insulin)

Procedure:

- Polymeric Core Formation:

- Prepare PNPs encapsulating the peptide/protein drug using the nanoprecipitation or single-emulsion method described in Section 3.2.

- Characterize the resulting PNPs for size and PDI before proceeding.

- Lipid Film Hydration:

- Dissolve lipids (lecithin, cholesterol, DSPE-PEG) in chloroform in a round-bottom flask.

- Remove solvent via rotary evaporation to form a thin, uniform lipid film.

- Hydrate the lipid film with an aqueous buffer to form liposomes.

- Down-size the liposomes by extrusion through polycarbonate membranes (100 nm pore size).

- Hybridization:

- Combine the prepared PNPs and liposomes in a 1:1 weight ratio.

- Sonicate the mixture using a probe sonicator (5-10 cycles of 30 seconds pulse, 45 seconds rest) at 4°C.

- Alternatively, use co-extrusion through membranes to facilitate fusion.

- Purification: Purify the resulting LPHNs by ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g for 45 minutes) to remove unincorporated lipids and polymers.

- Storage: Store the LPHN dispersion at 4°C or lyophilize with cryoprotectants.

Critical Parameters:

- The lipid-to-polymer ratio determines final hybrid architecture and surface properties [13].

- Sonication energy and time must be optimized to ensure complete fusion without damaging the payload [12].

Characterization Workflows and Techniques

Comprehensive characterization is imperative for correlating nanoparticle physicochemical properties with biological performance. The following workflow outlines critical quality attributes (CQAs) and corresponding analytical techniques.

Diagram: Comprehensive characterization workflow for nanoparticle analysis, linking physicochemical properties to functional performance.

Size and Morphology Analysis

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA):

- Principle: NTA utilizes light scattering and Brownian motion to determine particle size distribution and concentration in liquid suspensions [14] [16].

- Protocol:

- Dilute nanoparticle samples in purified water or PBS to achieve 20-100 particles per frame.

- Inject sample into the measurement chamber using a sterile syringe.

- Capture 60-second videos using camera level 12-16.

- Analyze at least three recordings per sample with detection threshold optimized for minimal background.

- Application: Particularly valuable for analyzing extracellular vesicles and heterogeneous LNP samples [16].

Electron Microscopy:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM):

- Protocol: Deposit nanoparticle suspension on silicon wafer, air-dry, and sputter-coat with gold/palladium before imaging.

- Output: High-resolution surface morphology and size verification [14].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM):

- Protocol: Apply sample to carbon-coated grid, stain with uranyl acetate, and image under appropriate magnification.

- Output: Internal structure visualization and core-shell confirmation in hybrid systems [12].

Drug Loading and Release Kinetics

Encapsulation Efficiency (EE) and Drug Loading (DL):

- Protocol:

- Separate unencapsulated drug using size exclusion chromatography or ultracentrifugation.

- Lyse nanoparticles using organic solvent (for lipid systems) or surfactant (for polymeric systems).

- Quantify drug content using validated UV-Vis, HPLC, or fluorescence spectroscopy methods.

- Calculations:

- EE (%) = (Amount of encapsulated drug / Total drug input) × 100

- DL (%) = (Weight of encapsulated drug / Total nanoparticle weight) × 100

In Vitro Release Kinetics:

- Protocol:

- Place nanoparticle suspension in a dialysis membrane (appropriate MWCO).

- Immerse in release medium (PBS, pH 7.4 with 0.1-0.5% surfactant to maintain sink conditions).

- Maintain at 37°C with constant agitation.

- Withdraw aliquots at predetermined time points and replace with fresh medium.

- Analyze drug content using appropriate analytical methods.

- Plot cumulative release versus time to determine release profile.

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy:

- Application: Confirms polymer structure, monitors polymerization conversion, and quantifies drug-polymer conjugation efficiency [11].

- Protocol:

- Dissolve nanoparticles in deuterated solvent (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O).

- Acquire ¹H NMR spectrum with sufficient scans for signal-to-noise ratio.

- Analyze characteristic peaks to verify successful conjugation and quantify loading.

Fluorescence-Based Single Particle Analysis:

- Application: Quantitative analysis of marker abundance on individual nanoparticles using fluorescent nanoparticle tracking analysis (fNTA) or nano-flow cytometry (nFCM) [16].

- Protocol:

- Label nanoparticles with fluorescent antibodies or dyes.

- Use reference fluorospheres with assigned equivalent reference fluorophore (ERF) values for calibration.

- Express fluorescent signal in ERF units to determine bound antibodies per particle.

- Combine with bulk measurements for comprehensive heterogeneity assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful nanoparticle development requires specialized materials and reagents with defined functions. The following table catalogs essential components for formulating advanced nanocarriers.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nanoparticle Formulation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | DLin-MC3-DMA, ALC-0315 | pH-responsive endosomal escape [9] | Critical for nucleic acid delivery; Optimize pKa for specific applications |

| Structural Lipids | DSPC, DOPE | Form nanoparticle structure and bilayer | Influence membrane fluidity and stability |

| Sterol Stabilizers | Cholesterol | Enhance membrane integrity and packing | Modulates stability and cellular uptake [9] |

| PEGylated Lipids | DMG-PEG2000, DSPE-PEG | Reduce opsonization, prolong circulation | Potential immunogenicity with repeated dosing [1] |

| Biodegradable Polymers | PLGA, PLA, PCL | Form stable nanoparticle matrix | Degradation rate controls drug release kinetics [10] [13] |

| Functional Polymers | PEG-b-PLA, Chitosan | Enhance stability, mucoadhesion | PEG provides stealth properties; Chitosan for mucosal delivery [10] |

| Stimuli-Responsive Polymers | PBAEs, pH-sensitive polymers | Enable triggered drug release | Activate in response to tumor microenvironment [10] |

| Characterization Standards | Fluorescent beads, ERF standards | Instrument calibration and quantification | Enable cross-platform data comparison [16] |

The strategic selection and optimization of nanoparticle platforms require careful consideration of therapeutic objectives, cargo characteristics, and administration routes. Lipid nanoparticles excel in nucleic acid delivery with proven clinical success, polymeric nanoparticles offer superior control for sustained small molecule delivery, while hybrid systems represent a promising approach for complex biologics like peptides and proteins.

Standardized protocols for preparation, characterization, and analysis are fundamental for generating reproducible, clinically translatable nanomedicines. The experimental frameworks and comparative data presented in this application note provide a foundational resource for researchers developing nanoparticle-based therapeutics. As the field advances, integration of machine learning for formulation design [15], development of novel non-PEG stealth alternatives [1], and implementation of scalable manufacturing processes [2] will be critical for bridging the translational gap between preclinical promise and clinical reality.

The efficacy of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems is critically dependent on their ability to navigate a series of biological barriers. This application note details the primary hurdles—clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES), also known as the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS); endosomal entrapment following cellular uptake; and the heterogeneous Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect in solid tumors. We provide validated, quantitative data on these barriers and practical protocols to overcome them, framing this within the context of optimizing drug delivery protocols for clinical translation. The following table summarizes the impact and primary strategies for each barrier.

Table 1: Summary of Key Biological Barriers in Nanoparticle Drug Delivery

| Biological Barrier | Impact on Delivery | Primary Overcoming Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| RES/MPS Clearance | Rapid removal from blood (t½ < several minutes); <1% of injected dose typically reaches target site [17] | Surface PEGylation; MPS Blockade; Biomimetic camouflage [18] [17] [19] |

| Endosomal Entrapment | Traps >95% of internalized cargo, leading to lysosomal degradation [20] | Proton-sponge polymers; Fusogenic lipids; Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) [20] [19] |

| Heterogeneous EPR Effect | Highly variable nanoparticle accumulation in human tumors, limiting therapy predictability [21] [22] | Tumor vasculature modulation; Pharmacological priming; Physical methods (e.g., ultrasound) [23] [22] |

Protocol: Overcoming RES/MPS Clearance

Background and Principle

The Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS), historically termed the RES, is the primary system responsible for clearing particulate matter from the circulation. Resident macrophages in the liver (Kupffer cells) and spleen rapidly recognize, take up, and remove intravenously administered nanoparticles, often resulting in a blood half-life of only several minutes and leaving less than 1% of the injected dose to reach the intended target [17]. The principle of evasion involves engineering a "stealth" nanoparticle surface that minimizes opsonization (binding of serum proteins) and subsequent phagocytosis.

Detailed Methodology: Formulation of PEGylated LPD Nanoparticles

This protocol describes the synthesis of stable, PEGylated Liposome-Polycation-DNA (LPD) nanoparticles, which have demonstrated significantly reduced liver uptake and enhanced tumor delivery [18].

Materials

- Cationic Liposomes: Composed of DOTAP (or multivalent DSGLA) and Cholesterol at a 1:1 molar ratio.

- Nucleic Acids: siRNA (e.g., anti-luciferase GL3) and calf thymus DNA.

- Polycation: Protamine sulfate.

- PEG-lipid: DSPE-PEG2000.

- Buffers: Nuclease-free water, Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Equipment: Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) instrument, Zeta potential analyzer, Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) column (Sepharose CL 2B), Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM).

Step-by-Step Procedure

Prepare Core Complex:

- Mix 150 µl of suspension A (8.3 mM cationic liposomes + 0.2 mg/ml protamine) with 150 µl of solution B (0.16 mg/ml siRNA + 0.16 mg/ml calf thymus DNA) quickly.

- Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 10 minutes. The protamine and nucleic acids condense to form a compact, negatively charged core.

Form LPD Nanoparticles:

- The cationic liposomes from the core complex collapse onto the core via charge-charge interaction, subsequently fusing and reorganizing to form a nanoparticle coated with two lipid bilayers. The inner bilayer is stabilized ("supported") by the core [18].

PEGylate via Post-Insertion:

- Incubate the freshly prepared LPD suspension (300 µl) with 37.8 µl of a DSPE-PEG2000 micelle solution (10 mg/ml) at 50°C for 10 minutes.

- Allow the PEGylated LPD to cool and stabilize at room temperature for 10 minutes.

Purification and Characterization:

- Purify: Use size exclusion chromatography (Sepharose CL 2B) with PBS as the eluent to remove unincorporated lipids and free PEG.

- Characterize:

- Size & Distribution: Analyze by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). The expected diameter is 100-150 nm.

- Surface Charge: Measure zeta potential in 1 mM KCl. Successful PEGylation should result in a near-neutral zeta potential, indicating complete charge shielding.

- Structure: Confirm the distinct multilamellar structure using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) with negative staining.

Alternative Strategy: MPS Blockade

An alternative/complementary strategy is the temporal blockade of the MPS to saturate clearance mechanisms.

- Procedure: Pre-administer a "blocking" dose of empty nanoparticles (e.g., non-therapeutic liposomes) 1-24 hours before injecting the therapeutic nanoparticle dose [17]. The blocking dose saturates phagocytic cells, temporarily reducing their capacity to clear the second dose.

- Example: Intravenous administration of blank liposomes can enhance the tumor delivery of a subsequent dose of paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles by up to 150% [17].

- Considerations: The size, composition, and dose of the blocking agent are critical. Clinically relevant, biodegradable particles (e.g., empty liposomes) are preferred.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RES Evasion

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DSPE-PEG2000 | PEG-lipid for stealth coating; reduces opsonization and RES uptake [18] | Post-insertion method allows high surface density (~10 mol%) without disrupting nanoparticle integrity [18] |

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids (e.g., DSGLA) | Forms stable supported bilayer in LPD; enhances encapsulation of nucleic acids [18] | Multivalent lipids confer higher stability against PEG disruption compared to monovalent lipids like DOTAP [18] |

| Liposomal Clodronate | Macrophage depletion agent for MPS blockade; induces apoptosis in phagocytic cells [17] | Provides long-term blockade but has low clinical translation potential due to toxicity and prolonged immune suppression [17] |

| Gadolinium Chloride (GdCl3) | MPS function inhibitor; blocks Ca2+ channels in Kupffer cells [17] | Effective for preconditioning but associated with toxicity issues, including proinflammatory cytokine release [17] |

Protocol: Enhancing Endosomal Escape

Background and Principle

Most non-viral delivery vectors enter cells via endocytosis, resulting in their entrapment within endosomes. These endosomes mature into lysosomes, where the acidic environment and enzymes degrade the therapeutic cargo. It is estimated that the endosomal escape process is highly inefficient, with only a few percent of the internalized cargo successfully reaching the cytosol [20]. Strategies to overcome this barrier are designed to disrupt the endosomal membrane in a controlled manner, facilitating the cytosolic release of the payload.

Detailed Methodology: Employing pH-Sensitive LNPs for siRNA Delivery

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) containing ionizable cationic lipids are a leading platform for nucleic acid delivery, leveraging the proton sponge effect and membrane fusion for escape [19].

Materials

- Lipids: Ionizable cationic lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA), Phospholipid (e.g., DSPC), Cholesterol, PEGylated lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG2000).

- Aqueous Buffer: Citrate buffer (pH 4.0).

- Therapeutic Payload: siRNA.

- Equipment: Microfluidic mixer or tube vortexer, DLS instrument.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Prepare Lipid Mixture: Dissolve the ionizable cationic lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid in ethanol at a specific molar ratio (e.g., 50:10:38.5:1.5 mol%).

- Prepare Aqueous Phase: Dissolve the siRNA in a citrate buffer (pH 4.0).

- Rapid Mixing:

- Microfluidic Method: Simultaneously pump the ethanolic lipid solution and the aqueous siRNA solution into a microfluidic chip at a controlled flow rate and ratio (typically 1:3 to 1:5, aqueous-to-ethanol) to form LNPs.

- Vortexing Method: Rapidly inject the ethanolic lipid solution into the aqueous siRNA solution under vigorous vortexing.

- Buffer Exchange and Dialysis: Dialyze the formed LNP suspension against a large volume of PBS (pH 7.4) for several hours to remove ethanol and raise the pH.

- Characterization: Determine particle size (expected 80-100 nm), polydispersity index (PDI < 0.2), and siRNA encapsulation efficiency (using a Ribogreen assay).

Mechanism of Action

The ionizable cationic lipids are neutral at physiological pH (7.4) but acquire a positive charge in the acidic environment of the endosome (pH ~5.5-6.5). This leads to:

- Proton Sponge Effect: The lipids buffer the endosomal pH, causing continued proton influx and chloride ion entry, leading to osmotic swelling and endosomal rupture [20].

- Membrane Fusion/Destabilization: The positively charged lipids interact with and destabilize the anionic endosomal membrane, promoting fusion or pore formation and releasing the cargo into the cytosol [19].

Protocol: Addressing Heterogeneity of the EPR Effect

Background and Principle

The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect is the cornerstone of passive targeting in solid tumors. However, its effectiveness in humans is highly heterogeneous, influenced by factors such as tumor type, size, stage, and blood flow [21] [22]. Advanced large tumors often have compromised blood flow due to thrombus formation and high interstitial pressure, leading to a poor EPR effect [21] [22]. The principle of enhancement involves using pharmacological or physical interventions to modulate the tumor vasculature and microenvironment, thereby improving nanoparticle perfusion and accumulation.

Detailed Methodology: Pharmacological Priming with Vasoactive Agents

This protocol uses angiotensin II (AT-II) to transiently elevate systemic blood pressure, enhancing tumor blood flow and nanoparticle extravasation [22].

Materials

- Vasoactive Agent: Angiotensin II (AT-II), sterile solution.

- Nanoparticles: Therapeutic nanoparticles (e.g., Doxil, polymeric micelles).

- Animal Model: Mice with established solid tumors (e.g., subcutaneous xenografts).

- Equipment: IV injection setup, physiological monitoring equipment.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Tumor Model Preparation: Establish solid tumors in mice (e.g., 100-300 mm³ in volume).

- Administer Priming Agent:

- Inject AT-II intravenously at a low dose (e.g., 50-100 µg/kg) dissolved in saline.

- The injection induces a transient hypertensive episode that lasts approximately 10-15 minutes.

- Administer Nanoparticles:

- Inject the therapeutic nanoparticles intravenously precisely 1-2 minutes after the AT-II administration.

- The increased systemic blood pressure during the hypertensive window preferentially augments blood flow to the tumor due to its poorly regulated vasculature, thereby enhancing nanoparticle accumulation.

- Monitoring: Monitor animal blood pressure to confirm the hypertensive effect and ensure animal welfare.

Alternative Strategy: Vascular Normalization Therapy

An alternative strategy involves "normalizing" the disorganized tumor vasculature to improve perfusion and reduce hypoxia.

- Procedure: Administer an anti-angiogenic agent, such as an anti-VEGF receptor antibody (e.g., DC101) or a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (e.g., erlotinib), over several days (e.g., 100 µg/mouse, every other day for 6 days) prior to nanoparticle injection [22].

- Mechanism: This treatment prunes immature, leaky vessels and matures others, resulting in a more organized vascular network. This can lead to a more uniform distribution of nanoparticles, particularly those of smaller size (~12 nm), with studies showing up to a 3-fold increase in tumor accumulation [22].

Table 3: Strategies to Modulate the EPR Effect for Improved Drug Delivery

| Modulation Strategy | Example Agent | Mechanism of Action | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Priming | Angiotensin II (AT-II) [22] | Induces transient hypertension, increasing tumor blood flow and nanoparticle extravasation. | Selective increase in tumor accumulation due to defective vascular regulation in tumors [22]. |

| Vascular Normalization | Anti-VEGFR2 Antibody (DC101) [22] | Prunes immature vessels and normalizes the tumor vasculature, improving perfusion. | Up to 3-fold increase in tumor accumulation of smaller (~12 nm) nanoparticles [22]. |

| Physical Priming | Ultrasound with Microbubbles [23] | Mechanical disruption of vessel walls and ECM upon bubble oscillation/bursting, enhancing permeability. | Clinically evaluated for improving drug delivery, particularly in brain tumors [23]. |

| Stroma Modulation | Enzymes (e.g., Collagenase, Hyaluronidase) | Degrades dense extracellular matrix (ECM), reducing interstitial pressure and improving diffusion. | Enhanced penetration of nanoparticles into the tumor core, especially in fibrotic tumors [22]. |

In the development of nanoparticle-based therapeutics, Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) are fundamental measurable properties that define the identity, purity, efficacy, and safety of a drug product. For nanomedicines, CQAs present unique challenges due to their complex, multi-component three-dimensional structures which require careful design and orthogonal analysis methods [24]. The establishment of well-defined CQAs is particularly crucial for mRNA/Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) products and other nanotherapeutics, where the field is rapidly expanding beyond vaccines to encompass therapeutic applications including gene editing, protein replacement, and cancer therapies [25]. A systematic understanding of these attributes—size, zeta potential, surface chemistry, and stability parameters—enables researchers to ensure batch-to-batch consistency, optimize therapeutic performance, and meet regulatory expectations throughout the product lifecycle from early development to commercial manufacturing [26].

Defining the Core CQAs for Nanoparticle Therapeutics

Particle Size and Distribution

Particle size is a fundamental CQA that significantly influences a nanoparticle's biological behavior, including its biodistribution, cellular uptake, and ability to penetrate biological barriers [24]. The size determination of nanoparticles, however, is not straightforward, as different measurement techniques probe different physical dimensions of the particle [27]. Some techniques measure the physical core size, while others measure the hydrodynamic diameter, which includes the hydration layer surrounding the nanoparticle as it moves in solution [27] [28].

Table 1: Nanoparticle Size Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Measured Parameter | Size Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic diameter [27] | 1 nm - 10 μm [28] | Ensemble measurement; sensitive to aggregates [27] |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Hydrodynamic diameter [27] | 10 - 2000 nm [28] | Single-particle tracking; provides concentration [27] |

| Electron Microscopy (TEM/SEM) | Core particle dimensions [27] [28] | 1 nm - 10 μm [28] | Direct visualization; requires vacuum conditions [27] [28] |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Topographical height [27] [28] | 1 nm - 10 μm [28] | Three-dimensional profiling; can measure in liquid [27] [28] |

| Disc Centrifugation | Sedimentation diameter [27] | 5 nm - 100 μm [28] | High-resolution size distribution [27] |

For intravenous nanosuspensions, particle size is particularly critical, as the formation of larger particles (>5 μm) could lead to capillary blockade and embolism [29]. The size distribution also provides valuable information, revealing the presence of aggregates that may indicate poor dispersion stability [27].

Figure 1: Particle Size CQA Measurement Strategy

Zeta Potential

Zeta potential represents the electrokinetic potential at the slipping plane of a dispersed particle relative to the bulk fluid, providing an indirect measure of the net surface charge and the magnitude of electrostatic interactions within the system [30]. This parameter is critically important as it directly influences colloidal stability by determining the balance between attractive van der Waals forces and repulsive electrostatic forces between particles [30].

Table 2: Zeta Potential Ranges and Colloidal Stability

| Zeta Potential (mV) | Stability Behavior | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|

| 0 to ±5 | Rapid coagulation or flocculation [30] | Unsuitable for therapeutic use |

| ±10 to ±30 | Incipient instability [30] | Limited shelf-life; may require cold chain |

| ±30 to ±40 | Moderate stability [30] | Generally acceptable for therapeutics |

| ±40 to ±60 | Good stability [30] | Good shelf-life potential |

| > ±60 | Excellent stability [30] | High stability but may affect biocompatibility |

From a biological perspective, zeta potential significantly affects how nanoparticles interact with cellular membranes. Since most cellular membranes are negatively charged, nanoparticles with strongly cationic surfaces (zeta potentials greater than +30 mV) generally display increased cellular uptake but may also be associated with more toxicity due to cell wall disruption [31]. Conversely, strongly anionic nanoparticles (less than -30 mV) may exhibit reduced cellular interaction but potentially better stability profiles [31].

Surface Chemistry

Surface chemistry is a critical design parameter that governs nanoparticle interactions with biological systems, including protein adsorption, cellular uptake, biodistribution, and targeting efficiency [32]. The surface functionalization of nanoparticles can be achieved through various strategies, including covalent bonding, non-covalent adsorption, and the use of homo- or hetero-bifunctional cross-linkers [32].

The surface composition directly influences what is known as the "protein corona" that forms when nanoparticles enter biological fluids. This corona significantly alters the nanoparticle's identity and biological behavior [32]. Surface modification strategies can be broadly categorized into passive and active targeting approaches:

- Passive targeting relies on the intrinsic physical properties of nanoparticles (size, shape, superficial charge) to accumulate in target tissues through phenomena like the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect in tumors [32].

- Active targeting involves the biofunctionalization of nanoparticle surfaces with specific ligands (antibodies, peptides, aptamers, oligosaccharides) that have strong affinity for receptors overexpressed on target cells [32].

Table 3: Surface Functionalization Strategies by Nanoparticle Material

| Nanomaterial | Usable Functional Groups | Functionalization Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Silica | -SiOH | Aminosilanes for amine group introduction [32] |

| Noble Metals (Au, Ag) | Metallic surface (Au, Ag) | Thiol- or amine-based crosslinkers [32] |

| Metal Oxides | MOx | Ligand exchange with diol, amine, carboxylic acid, thiol [32] |

| Carbon-based | sp² hybridized carbon | Oxidation to generate -COOH, -OH, -C=O; halogenation [32] |

Stability Parameters

Stability is one of the most challenging aspects in nanomedicine development, crucial for ensuring both safety and efficacy of the final drug product [29]. Nanoparticle stability encompasses multiple dimensions: physical stability (particle size distribution, absence of aggregation), chemical stability (drug integrity, excipient compatibility), and biological stability (sterility, absence of endotoxins) [29].

The stability challenges vary significantly depending on the dosage form and route of administration. For instance, particle agglomeration presents different concerns in pulmonary delivery (where it affects aerodynamics) versus intravenous administration (where it may cause capillary embolism) [29]. Stability is influenced by numerous factors including the dispersion medium (aqueous vs. non-aqueous), production technique (top-down vs. bottom-up), and the inherent nature of the drug substance (small molecules vs. large biomolecules) [29].

Experimental Protocols for CQA Characterization

Protocol: Dynamic Light Scattering for Size and Size Distribution

Principle: DLS measures the fluctuations in scattered light intensity caused by Brownian motion of particles in suspension, which is correlated to their hydrodynamic diameter through the Stokes-Einstein equation [27] [28].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the nanoparticle suspension with an appropriate buffer to achieve optimal scattering intensity. Avoid over-dilution or concentration that may alter particle interactions. Filter the sample through a 0.22 μm or 0.45 μm filter to remove dust and large aggregates if necessary [27].

- Instrument Calibration: Use standard latex beads of known size (e.g., 100 nm) to verify instrument performance and alignment according to manufacturer specifications [28].

- Measurement Parameters:

- Temperature: Maintain constant temperature (typically 25°C) with controlled tolerance (±0.3°C)

- Measurement angle: Typically 90° or backscatter detection (173°)

- Run duration: 5-10 measurements of 60 seconds each for statistical reliability [27]

- Data Analysis:

- Report the Z-average diameter (mean hydrodynamic size) and polydispersity index (PDI)

- PDI < 0.1 indicates monodisperse system; 0.1-0.2 moderate polydispersity; >0.2 broad distribution [27]

- Examine the intensity-weighted distribution and consider volume- or number-weighted distributions for polydisperse samples [28]

Troubleshooting Tips:

- High PDI values may indicate aggregation or sample contamination

- If concentration is too high, multiple scattering can affect results

- Viscous solutions require adjustment of the viscosity parameter in software [27] [28]

Protocol: Zeta Potential Measurement via Electrophoretic Light Scattering

Principle: Zeta potential is determined by measuring the electrophoretic mobility of particles in an applied electric field and calculating the potential at the slipping plane using the Henry equation [31] [30].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples in a suitable aqueous medium with controlled ionic strength. For nanoparticles in non-aqueous media, specialized cells may be required. Dilute samples to avoid multiple scattering effects [31].

- Cell Selection and Loading: Use a clear disposable zeta cell or a dedicated folded capillary cell. Ensure no air bubbles are introduced during loading as they interfere with measurement [30].

- Measurement Parameters:

- Temperature: 25°C unless otherwise specified

- Field strength: Typically 10-20 V/cm depending on sample conductivity

- Measurement cycles: Minimum 10-12 runs per sample

- Attenuator setting: Optimize for count rate between 200-500 kcps [31]

- Data Analysis:

- Report the mean zeta potential and standard deviation from multiple measurements

- Examine the phase plot for stability of measurement

- Ensure the baseline correlation function fits properly for reliable results [30]

Quality Control:

- Validate instrument performance using standard reference materials (e.g., -50 mV ± 5 mV latex standards)

- Monitor the conductivity of the sample to ensure appropriate electrolyte concentration [31] [30]

Protocol: Surface Chemistry Analysis Through FTIR and ζ-Potential

Principle: Surface functional groups can be characterized using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to identify chemical bonds, while surface charge changes confirm successful modification [32].

Procedure for FTIR Analysis:

- Sample Preparation:

- For dry nanoparticles: Use KBr pellet method or attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode

- For suspensions: Concentrate nanoparticles by centrifugation and prepare as thin film on ATR crystal [32]

- Measurement Parameters:

- Spectral range: 4000-400 cm⁻¹

- Resolution: 4 cm⁻¹

- Scans: 64-128 for acceptable signal-to-noise ratio

- Data Interpretation:

- Identify characteristic absorption bands: amine groups (3300-3500 cm⁻¹), carbonyl (1650-1750 cm⁻¹), carboxylate (1400-1600 cm⁻¹)

- Compare spectra before and after surface modification to confirm functionalization [32]

Complementary ζ-Potential Measurement:

- Measure ζ-potential before and after surface modification

- Significant changes in ζ-potential confirm surface charge modification (e.g., increase in positive charge after amine functionalization) [32]

Figure 2: Surface Chemistry Characterization Workflow

Stability Assessment Protocols

Comprehensive Stability Study Design

Principle: Stability of nanoparticle formulations must be evaluated under various stress conditions to predict shelf-life and identify potential failure modes [29]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines provide framework for stability testing, but nanoparticle formulations often require additional specific assessments.

Protocol:

- Accelerated Stability Testing:

- Store samples at elevated temperatures (e.g., 4°C, 25°C, 40°C) for predetermined timepoints (1, 3, 6 months)

- Assess size, PDI, zeta potential, drug content, and related substances at each interval [29]

- Freeze-Thaw Stability:

- Subject samples to multiple freeze-thaw cycles (-20°C to 25°C)

- Evaluate physical stability after each cycle [29]

- In-Use Stability:

- For lyophilized products: reconstitute and monitor over recommended in-use period

- For suspensions: evaluate under simulated administration conditions [29]

Parameters for Stability Assessment:

- Physical stability: Particle size, size distribution, appearance, pH, redispersibility

- Chemical stability: Drug assay, related substances, degradation products

- Performance stability: Drug release profile, encapsulation efficiency [29]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Nanoparticle CQA Assessment

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Size Characterization | Latex size standards (100 nm, 200 nm) [28] | Instrument calibration and verification |

| Zeta Potential Standards | Colloidal gold (strongly anionic) [31] | Negative zeta potential reference |

| Amine-terminated PAMAM dendrimer (strongly cationic) [31] | Positive zeta potential reference | |

| Surface Modification | Aminosilanes (e.g., APTES) [32] | Silica nanoparticle functionalization |

| Thiol-carboxylic acids [32] | Gold nanoparticle surface modification | |

| Heterobifunctional crosslinkers (e.g., NHS-PEG-Maleimide) [32] | Bioconjugation and PEGylation | |

| Stabilizers | Poloxamers, Polysorbates [29] | Steric stabilization against aggregation |

| Ionic surfactants (SDS, CTAB) [29] | Electrostatic stabilization | |

| Cyclodextrins [29] | Complexation and stabilization | |

| Characterization Kits | Commercial mRNA purity/integrity kits [25] | mRNA nanoparticle quality assessment |

| dsRNA detection kits [25] | Impurity quantification in mRNA products |

Integration of CQAs in Nanomedicine Development

The successful development of nanoparticle-based therapeutics requires a systematic approach to CQA identification and control throughout the product lifecycle. For mRNA/LNP products, CQAs can be categorized into five main groups: purity and product-related impurities; safety tests; strength, identity, and potency; product quality and characteristics; and other obligatory CQAs [25]. Early product characterization is crucial for distinguishing between critical and non-critical quality attributes, with the understanding that even non-critical attributes can provide valuable information about product behavior and process consistency [25].

A significant challenge in nanomedicine development is establishing meaningful potency assays that adequately reflect the product's biological activity. For complex nanoparticles, a matrix approach for potency assessment is often necessary, capturing multiple aspects of function including transfection efficiency, translation capability, and biological activity of the encoded protein [25]. As the field matures, increased regulatory guidance and industry consensus on CQA assessment will hopefully accelerate the clinical translation of promising nanomedicines while ensuring product quality, safety, and efficacy [26] [25] [24].

Advanced Formulation Strategies and Delivery System Engineering

Nanoprecipitation, also known as solvent displacement or the "Ouzo effect," has emerged as a versatile and efficient technique for formulating nanoparticles (NPs), providing significant advantages in drug delivery applications [33] [34]. This method relies on the controlled mixing of a water-miscible organic solvent containing dissolved solute molecules with an anti-solvent (typically water), leading to rapid supersaturation and the formation of nanoscale particles [33]. The technique has evolved from simple batch operations to sophisticated continuous processes, enabling precise control over particle size, morphology, and drug release profiles [34]. Within nanoparticle-based drug delivery protocol optimization research, selecting the appropriate nanoprecipitation method is crucial for achieving reproducible and scalable production of nanocarriers with defined critical quality attributes (CQAs). This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for conventional, flash, and microfluidic nanoprecipitation techniques, supporting their implementation in optimized drug delivery system development.

Technical Comparison of Nanoprecipitation Platforms

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of three primary nanoprecipitation platforms, providing researchers with a comparative framework for technique selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nanoprecipitation Platforms for Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Parameter | Conventional Batch Nanoprecipitation | Flash Nanoprecipitation (FNP) | Microfluidic Nanoprecipitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing Principle | Dropwise addition or pipette mixing in unstirred or stirred vessels [33] | Turbulence-enhanced rapid mixing in confined impingement jets (CIJ) or multi-inlet vortex mixers (MIVM) [33] [34] | Laminar flow with diffusion-controlled or chaotic advection mixing in microfabricated channels [35] [36] |

| Mixing Timescale | Seconds to minutes [35] | Milliseconds [33] [34] | Milliseconds to seconds [35] |

| Typical Particle Size Range | 50 - 500 nm [33] | 20 - 200 nm [37] | 50 - 300 nm [35] [36] |

| Size Distribution (PDI) | Moderate to broad (>0.1) [36] | Narrow (<0.1) [33] [37] | Very narrow (<0.1) [35] [36] |

| Drug Encapsulation Efficiency | Varies with drug hydrophobicity | High for highly hydrophobic drugs [37] | High and reproducible [35] |

| Throughput & Scalability | Limited by mixing heterogeneity; scaled up via volume increase | Highly scalable via reactor numbering-up or continuous operation [34] | Scalable via channel parallelization; inherently continuous [35] [36] |

| Key Advantages | Operational simplicity, low equipment cost, minimal material needs [33] | Superior size control, batch-to-batch consistency, handles high supersaturation [33] [34] | Unparalleled mixing control, high reproducibility, tunable release kinetics [35] [36] |

| Primary Limitations | Broader size distribution, batch-to-batch variability, limited mixing control [33] [36] | Specialized mixer design required, optimization for different formulations needed | Potential for channel clogging, fabrication complexity, higher entry level [35] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Conventional Batch Nanoprecipitation of PLGA Nanoparticles

This protocol outlines the optimized synthesis of Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles using a batch method, refined through Design of Experiments (DoE) [36].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Batch PLGA Nanoprecipitation

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA | Resomer RG 502 H, Mw 7000–17,000 Da | Biodegradable polymer matrix for nanoparticle formation [36] |

| Organic Solvent | Acetonitrile (ACN, 99.95%) | Solvent for dissolving PLGA polymer [36] |

| Aqueous Phase Surfactant | Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, 9000–10,000 Mw, 80% hydrolyzed) | Stabilizer to prevent nanoparticle aggregation [36] |

| Anti-Solvent | Deionized Water | Aqueous phase inducing polymer precipitation [36] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Dissolve PVA in deionized water to a final concentration of 1.5% - 2.5% (w/v). Use a volume between 1 mL and 3 mL. Stir until completely clear [36].

- Organic Phase Preparation: Dissolve 5 mg - 15 mg of PLGA polymer in 100 μL - 500 μL of acetonitrile [36].

- Mixing and Nanoprecipitation: Place the aqueous PVA solution in a 5 mL cylindrical glass vial with a 3 mm × 10 mm magnetic stir bar. Stir continuously at 660 rpm. Add the organic phase dropwise to the aqueous phase every three seconds using a micropipette [36].

- Solvent Evaporation: Allow the mixture to incubate overnight at room temperature, uncovered, with gentle stirring to ensure complete evaporation of the organic solvent [36].

- Purification: Transfer the nanoparticle suspension to centrifuge tubes. Wash twice by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 20 minutes per cycle. Carefully decant the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in deionized water each time [36].

- Lyophilization: Freeze the purified nanoparticle suspension and lyophilize using a standard freeze-dryer (e.g., Kühner Alpha 2-4 LD) to obtain a dry powder for long-term storage [36].

Hydrodynamic and Statistical Analysis

For the described setup (660 rpm, 10 mm impeller), the Reynolds number (Re) is approximately 125, indicating laminar flow. The Damköhler number (Da), with a mixing time (t~mix~) of ~0.91 s and a reaction time (t~react~) of ~0.1 s, is about 0.11. A Da < 1 suggests that the mixing process is slower than the precipitation reaction, which can lead to heterogeneity. This highlights the limitation of batch methods and the need for precise control over addition rates and stirring [36]. DoE analysis reveals that the PLGA/ACN ratio and aqueous-to-organic volume ratio are statistically significant predictors (p < 0.05) of both nanoparticle size and PDI [36].

Protocol: Flash Nanoprecipitation (FNP) Using a Confined Impingement Jet (CIJ) Mixer

FNP achieves ultra-rapid mixing to produce nanoparticles with narrow size distributions, ideal for encapsulating hydrophobic drugs [33] [37].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Flash Nanoprecipitation

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer & Drug | e.g., PLGA and a hydrophobic drug (Itraconazole, β-carotene) | Forms the core matrix of the nanoparticle; drug is the therapeutic payload [37] |

| Stabilizer Block Copolymer | e.g., Poloxamer (Pluronic) | Forms a steric stabilization shell around the nanoparticle core to prevent aggregation [37] |

| Organic Solvent | Tetrahydrofuran (THF) or Acetone | Water-miscible solvent for polymer, drug, and stabilizer [33] |

| Anti-Solvent | Deionized Water or Buffer | Aqueous phase triggering instantaneous nanoprecipitation upon mixing [33] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation:

- Organic Stream: Dissolve the polymer (e.g., PLGA), drug, and amphiphilic block copolymer stabilizer (e.g., Poloxamer 407) in THF. A typical total solid concentration is 1-10 mg/mL [37].

- Aqueous Stream: Use pure deionized water or a buffer as the anti-solvent.

- Mixer Setup: Connect two high-precision syringe pumps to the two inlets of a CIJ mixer. Load one pump with the organic solution and the other with the aqueous anti-solvent.

- Flash Mixing: Simultaneously drive the two streams into the mixing chamber at high flow rates (typical total flow rate 10-60 mL/min). The impingement of jets creates intense turbulence, achieving mixing in milliseconds [33] [34].

- Collection and Solvent Removal: Collect the effluent nanoparticle suspension. If THF is used, remove the residual organic solvent by gentle evaporation or dialysis against water.

- Purification and Characterization: Purify the nanoparticles via tangential flow filtration or centrifugation. Characterize for size, PDI, zeta potential, and drug encapsulation efficiency.

Protocol: Microfluidic Nanoprecipitation Using a Staggered Herringbone Micromixer (SHM)

Microfluidics offers exceptional control over mixing kinetics, enabling the synthesis of highly uniform nanoparticles with tunable properties [35] [36].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Microfluidic Nanoprecipitation

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer | PLGA or other biodegradable polymers | Nanoparticle structural polymer [36] |

| Organic Solvent | Acetonitrile (ACN) | Dissolves the polymer for the organic phase [36] |

| Aqueous Phase Stabilizer | PVA solution or other surfactants | Aqueous stream stabilizer to control particle growth and stability [36] |

| Microfluidic Chip | Staggered Herringbone Mixer (SHM) geometry | Generates chaotic advection to enhance mixing efficiency in laminar flow [35] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation:

- Chip Priming and Setup: Load the organic and aqueous solutions into separate syringes and mount them on a multi-syringe pump. Connect the syringes to the inlets of the SHM chip. Prime the channels to remove air bubbles.

- Microfluidic Mixing: Initiate flow. A common configuration uses a three-inlet junction, with the organic phase in the central inlet flanked by two aqueous phase inlets [36]. The SHM's asymmetric grooves induce chaotic advection, reducing the mixing time (τ~m~) to milliseconds. Key parameters to control are:

- Collection and Processing: Collect the nanoparticle suspension from the outlet stream into a vial. The solvent can be evaporated under reduced pressure or dialyzed.

- Post-processing: Purify and lyophilize the nanoparticles as described in Section 3.1.2.

Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

Nanoparticle Formation Mechanism in Nanoprecipitation

The following diagram illustrates the kinetic processes governing nanoparticle formation during mixing, which is fundamental to understanding the differences between nanoprecipitation techniques.

Figure 1. Nanoparticle Formation Kinetics During Mixing. The pathway is determined by the relationship between the mixing timescale (τ~m~) and the nucleation timescale (τ~n~). When τ~m~ < τ~n~ (blue path), rapid mixing creates a homogeneous supersaturation environment, favoring homogeneous nucleation and yielding small, uniform NPs. When τ~m~ > τ~n~ (red path), mixing is slow relative to nucleation, leading to heterogeneous growth and aggregation, resulting in larger, polydisperse NPs [35].

Microfluidic Nanoprecipitation Workflow

The diagram below outlines the integrated experimental and computational workflow for optimizing nanoparticle synthesis using a microfluidic platform.

Figure 2. Microfluidic Optimization Workflow for Nanoparticle Synthesis. This integrated approach combines experimental synthesis with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling. Formulation parameters guide both the experimental process and the setup of CFD simulations, which model flow and concentration profiles to analyze mixing efficiency. The simulation results inform microfluidic design and operation, while experimental data validates the models, culminating in an optimized nanoparticle formulation with defined Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) [36].

Application Notes for Drug Delivery Protocol Optimization

Selecting a Nanoprecipitation Technique

The choice of technique represents a trade-off between control, simplicity, and scalability, and should be aligned with the stage and goals of the research [33] [35] [36].

- Conventional Batch is ideal for initial formulation screening and feasibility studies due to its low material consumption and minimal equipment requirements.

- Flash Nanoprecipitation is superior for producing high volumes of nanoparticles with narrow size distributions, particularly for highly hydrophobic drugs, and is easier to scale than microfluidics [37].

- Microfluidic Platforms provide the highest level of precision and reproducibility for establishing robust structure-activity relationships and are excellent for producing complex nanostructures like core-shell particles [35] [36].

Addressing the Translational Gap