Overcoming the Blood-Brain Barrier: Advanced Drug Delivery Strategies for Neurodegenerative Diseases

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest strategies to overcome the blood-brain barrier (BBB) for effective drug delivery to the central nervous system.

Overcoming the Blood-Brain Barrier: Advanced Drug Delivery Strategies for Neurodegenerative Diseases

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest strategies to overcome the blood-brain barrier (BBB) for effective drug delivery to the central nervous system. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of the BBB, evaluates cutting-edge methodological approaches like receptor-mediated transcytosis and focused ultrasound, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges in translational research, and offers a comparative validation of emerging technologies. The content synthesizes recent preclinical advances, clinical trial data, and industry trends to present a holistic view of the rapidly evolving landscape in neurotherapeutics.

The Blood-Brain Barrier: Understanding the Guardian of the CNS

Anatomical and Cellular Composition of the Neurovascular Unit

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the neurovascular unit (NVU) and why is it critical for central nervous system drug delivery?

The neurovascular unit (NVU) is a multicellular complex that forms a functional interface between the blood circulation and the central nervous system (CNS). It serves as the structural and physiological basis for the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [1] [2]. The primary function of the NVU is to maintain CNS homeostasis by regulating the delicate brain microenvironment, protecting neural tissue from toxins and pathogens, and controlling the passage of nutrients and metabolites [1] [3]. For drug delivery, the NVU presents a significant challenge because its tightly regulated barrier properties prevent more than 98% of small-molecule drugs and nearly 100% of large-molecule therapeutics from reaching the brain [3] [4]. Understanding its composition is therefore essential for developing strategies to overcome this barrier for treating neurological disorders.

Q2: Which specific cell types form the core components of the NVU?

The NVU consists of a core ensemble of specialized cells working in concert. The key cellular components include:

- Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells (BMECs): These cells line the cerebral blood vessels and form the primary physical barrier through tight junctions, drastically limiting paracellular transport [3] [4].

- Pericytes: These mural cells are embedded in the basement membrane and are central to regulating vasomotion, cerebral blood flow, and maintaining BBB stability [3] [2].

- Astrocytes: Their star-shaped end-feet extensively cover the abdominal surface of blood vessels. They provide structural and metabolic support to endothelial cells and help regulate BBB function [3] [2].

- Neurons: As the "pacemakers" of the NVU, neurons signal their metabolic demands, which in turn regulates vascular tone and blood flow to meet energy requirements [1] [5].

- Microglia and Oligodendrocytes: These glial cells contribute to immune surveillance and axonal myelination, respectively, further supporting the NVU's integrated function [2].

Q3: Our drug candidate shows poor penetration in an in vivo model. What are the primary barrier functions of the NVU that could explain this?

The NVU limits drug penetration through several coordinated mechanisms:

- Physical Barrier: Tight junctions (composed of proteins like claudin, occludin, and ZO-1) between endothelial cells severely restrict the paracellular (between cells) diffusion of most molecules [6] [3].

- Transport Barrier: Selective transport systems allow only specific substances to cross.

- Efflux Pumps: ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters like P-glycoprotein (P-gp) actively pump a wide range of foreign compounds, including many drugs, back into the bloodstream [6] [4].

- Nutrient Transporters: Carrier-mediated transport (CMT) systems exist for essential nutrients (e.g., GLUT1 for glucose), but they are highly selective [7] [4].

- Enzymatic Barrier: The endothelial cells exhibit enzymatic activity capable of degrading certain molecules before they can cross the BBB [6].

- Receptor-Mediated Control: Specific receptors facilitate the transcytosis of large molecules (e.g., via transferrin receptor), but this process is tightly regulated [4].

The table below summarizes the key quantitative barriers a drug may encounter.

Table 1: Key Barrier Properties of the Neurovascular Unit Impacting Drug Delivery

| Barrier Type | Key Components | Functional Impact on Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Barrier | Tight Junctions (Claudin-5, Occludin) [8] | Prevents paracellular diffusion of >95% of potential therapeutics [7]. |

| Efflux Transport | P-glycoprotein (P-gp), BCRP, MRPs [6] [4] | Recognizes and actively effluxes >60% of marketed drugs [7]. |

| Size/Lipophilicity Limit | Continuous endothelial membrane [7] | Effectively restricts passive diffusion to small (<400-600 Da), lipophilic molecules [3]. |

| Enzymatic Degradation | Cytochrome P450 enzymes and others [6] | Metabolizes drugs at the barrier, reducing bioavailability [6]. |

Q4: We observe regional differences in drug delivery efficacy in the brain. Is the NVU uniform throughout the CNS?

No, the NVU exhibits significant regional heterogeneity, which can lead to varying drug delivery outcomes [8]. Key differences include:

- Gray vs. White Matter: The metabolic demands and vascular architecture differ. Glucose consumption is 2–4 times greater in synapse-rich gray matter [8]. Some evidence suggests endothelial cells in white matter form a tighter paracellular barrier under normal conditions but may be more susceptible to pathological hyperpermeability [8].

- Vascular Tree Location: The properties of NVU cells vary along the arteriole-capillary-venule axis. For example, gene expression in endothelial cells and the phenotypes of pericytes differ depending on their position [8].

- Circumventricular Organs (CVOs): Regions like the area postrema lack a tight BBB, allowing a more active exchange between blood and the CNS, which can be exploited for drug delivery [6] [8].

This heterogeneity means that a one-size-fits-all approach to brain drug delivery is unlikely to be successful.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q5: Our in vitro BBB model shows unusually low transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER). What could be the cause?

Low TEER indicates a leaky barrier, often due to incomplete formation or damage to tight junctions. Consider the following troubleshooting steps:

- Verify Cell Source and Quality: Primary BMECs or stem cell-derived BMECs should express high levels of tight junction proteins (claudin-5, occludin). Check protein expression via immunocytochemistry [2].

- Review Co-culture Conditions: A proper NVU model often requires co-culture with pericytes and astrocytes, which secrete signaling factors that enhance barrier integrity. Ensure your model includes these supportive cells or their conditioned media [3] [2].

- Check Culture Duration: TEER can take several days to reach a stable, high plateau. Measure TEER over time to ensure the model has matured sufficiently.

- Assess Media Components: Certain growth factors (e.g., VEGF) can increase permeability. Use specialized media formulations designed to promote a barrier phenotype, often involving hydrocortisone and cAMP analogs.

Q6: In our animal studies, how can we distinguish if a drug is crossing the BBB via passive diffusion or active transport?

Distinguishing the transport mechanism is key for optimization. The following experimental approaches can be used:

- Inhibitor Studies: Use specific inhibitors for transport pathways.

- To test for efflux by P-gp, co-administer a known P-gp inhibitor like verapamil or elacridar. An increase in brain concentration of your drug suggests it is a P-gp substrate [6].

- To test for carrier-mediated transport (CMT), use an excess of a natural substrate (e.g., D-glucose for GLUT1). A reduction in your drug's uptake suggests it uses that transporter [4].

- Saturability Assay: Administer increasing doses of the drug. Active transport processes (both influx and efflux) are saturable, while passive diffusion is not. A non-linear relationship between plasma exposure and brain uptake suggests an active process [4].

- Enantiomer Comparison: If your drug is a racemic mixture, test the brain uptake of individual enantiomers. Carrier systems are often stereospecific, while passive diffusion is not.

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Investigating Drug Transport Mechanisms

| Target Mechanism | Experimental Approach | Key Reagents & Methods | Interpretation of Positive Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-gp Efflux | Co-administration with P-gp inhibitor [6] | Elacridar (GW572016) or Tariquidar; administered IV or IP prior to drug. | Significant increase in brain-to-plasma ratio compared to control. |

| Carrier-Mediated Influx | Saturation and competition studies [4] | Co-perfusion with high concentration of natural substrate (e.g., glucose for GLUT1). | Significant reduction in drug uptake in the brain. |

| Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis | Ligand competition assay [4] | Co-administration with excess unlabeled ligand (e.g., transferrin for TfR). | Reduction in brain uptake of the drug candidate. |

| General Active Transport | Dose-dependence study [4] | IV administration of drug across a wide dose range. | Non-linear (saturable) brain uptake kinetics. |

Key Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated signaling between major cell types within the NVU that maintains barrier integrity and regulates blood flow.

NVU Signaling Network

Detailed Protocol: Assessing the Role of a Specific Receptor in RMT

Objective: To validate whether a drug conjugate targeting the Transferrin Receptor (TfR) undergoes Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT) across an in vitro BBB model.

- Model Establishment: Use a well-characterized in vitro BBB model, such as a Transwell system with primary BMECs or induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived BMECs, preferably in co-culture with astrocytes and/or pericytes. Validate model integrity by measuring TEER (>150 Ω·cm² is often acceptable) [2].

- Ligand Conjugation: Conjugate your drug payload to a validated ligand for the target receptor (e.g., an anti-TfR antibody or the transferrin protein itself).

- Competitive Inhibition Assay:

- Pre-incubate the BMECs with a large excess (e.g., 10-100x molar ratio) of unlabeled ligand (e.g., apo-transferrin) for 30-60 minutes to saturate the receptors.

- Add the fluorescently or radio-labeled drug conjugate to the apical (blood) compartment.

- Incubate for a set time (e.g., 2-4 hours).

- Sample Collection and Analysis: Collect samples from the basolateral (brain) compartment. Quantify the amount of drug conjugate that has translocated using an appropriate method (e.g., fluorescence, radioactivity, LC-MS).

- Data Interpretation: A statistically significant reduction in the transport of the drug conjugate in the competition group compared to the control (no competitor) provides strong evidence that transport is specifically mediated by the TfR pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Neurovascular Unit and BBB Permeability Research

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Experiment | Example Specifics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary BMECs / iPSC-BMECs | Form the core barrier layer in in vitro models [2]. | Must express high levels of tight junction proteins and functional efflux transporters. |

| Transwell/Cell Culture Inserts | Provide a semi-permeable membrane for co-culture and permeability assays [2]. | Polycarbonate or polyester membranes with 0.4-3.0 µm pores are standard. |

| TEER Measurement System | Quantifies the integrity and tightness of the cellular barrier in real-time [2]. | Uses a voltmeter and electrodes (chopstick or EndOhm). TEER >150 Ω·cm² is a common quality threshold. |

| P-gp Inhibitors (e.g., Elacridar) | Pharmacologically blocks the P-glycoprotein efflux pump to assess its role in limiting drug uptake [6]. | Used in both in vitro and in vivo studies. |

| Tight Junction Protein Antibodies | Visualize and quantify (via ICC/IHC) the expression and localization of claudin-5, occludin, ZO-1 [8] [3]. | Critical for validating the quality of in vitro models and assessing BBB damage in tissue. |

| Paracellular Tracers (e.g., FITC-Dextran) | Measure nonspecific paracellular leakage in in vitro models or in vivo [7]. | Commonly used sizes are 4 kDa and 70 kDa. |

| In Vivo Imaging Agents | Visualize BBB disruption and drug distribution in animal models [2]. | Includes Evans Blue dye, MRI contrast agents (Gadolinium), and PET tracers. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary cellular components that contribute to the blood-brain barrier's physiological barrier function? The BBB's barrier function is primarily established by specialized brain microvascular endothelial cells that are interconnected by tight junctions [9] [10]. These endothelial cells are supported by and interact with pericytes embedded in the capillary basement membrane and the end-feet of astrocytes [9] [3] [11]. This multicellular ensemble, often referred to as the neurovascular unit, works in concert to create a highly selective barrier [10].

FAQ 2: Which specific tight junction proteins are most critical for maintaining the high electrical resistance and low paracellular permeability of the BBB? Claudin-5 is recognized as the dominant tight junction protein at the BBB and is particularly critical for sealing the paracellular pathway to small molecules [10]. Other key proteins include occludin and the junctional adhesion molecule (JAM-A), all of which are stabilized to the endothelial cell membrane by scaffolding proteins like zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) [10] [12]. The balance and interaction between these proteins, rather than the level of a single protein alone, are crucial for overall tight junction integrity [10].

FAQ 3: How do efflux transporters at the BBB limit the brain penetration of therapeutic drugs, and which one is most commonly associated with multidrug resistance? Efflux transporters are ATP-dependent pumps located on the luminal membrane of brain endothelial cells that actively transport a wide range of xenobiotics back into the blood circulation [13] [4]. The most prominent and well-studied efflux transporter is P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which is associated with multidrug resistance and can limit the distribution of many beneficial CNS therapeutics [13] [3] [14].

FAQ 4: What types of metabolic enzymes are present at the BBB, and what is their role? The BBB expresses a complement of drug-metabolizing enzymes that form a metabolic barrier [10]. These enzymes are capable of inactivating therapeutics or altering their chemical structure during the process of crossing the endothelial cells, thereby reducing the amount of active drug that reaches the brain parenchyma [10].

FAQ 5: Under what pathological conditions does the integrity of the BBB become compromised? BBB integrity can be compromised in a wide range of acute and chronic neurological conditions [9] [13]. Key examples include:

- Neurodegenerative diseases: Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [15] [13].

- Acute insults: Ischemic stroke, traumatic brain injury, and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy [9] [13].

- Other conditions: High-grade gliomas, multiple sclerosis, and hepatic encephalopathy [9] [11]. This dysfunction often involves disruption of tight junctions and increased permeability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Investigating P-gp Mediated Efflux of a Lead Compound

Problem: A promising small molecule drug shows excellent potency in cellular assays but demonstrates poor brain penetration in vivo, despite favorable molecular weight and lipophilicity.

Investigation Hypothesis: The compound is a substrate for the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux pump, limiting its brain accumulation.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol:

Step 1: In Vitro Transport Assay

- Objective: To assess the compound's directional transport and potential for active efflux.

- Method: Use a validated model of the BBB, such as MDCK-MDR1 or hCMEC/D3 cells seeded on Transwell inserts. The MDCK-MDR1 cell line is a canine kidney epithelial cell line engineered to overexpress human P-gp.

- Procedure:

- Seed cells on permeable membrane supports and culture until a confluent monolayer with high TEER is formed.

- Add the test compound to either the apical (A) or basolateral (B) compartment in a transport buffer (e.g., HBSS or PBS, pH 7.4).

- Incubate at 37°C and sample from the opposite compartment at predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes).

- Analyze samples using LC-MS/MS or HPLC to determine compound concentration.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the apparent permeability (Papp) and the efflux ratio (ER).

- Papp (cm/s) = (dQ/dt) / (A × C0), where dQ/dt is the rate of permeation, A is the membrane surface area, and C0 is the initial donor concentration.

- ER = Papp (B to A) / Papp (A to B).

- An ER > 2 suggests active efflux.

Step 2: Confirmatory Assay with P-gp Inhibition

- Objective: To confirm that the observed efflux is specifically mediated by P-gp.

- Method: Repeat the transport assay in the presence of a selective and potent P-gp inhibitor (e.g., Zosuquidar (LY335979) or Tariquidar).

- Procedure:

- Pre-incubate the cell monolayers with the inhibitor (e.g., 2 µM Zosuquidar) for a set time (e.g., 1 hour).

- Perform the A-to-B and B-to-A transport assays as in Step 1, maintaining the inhibitor in the buffer throughout the experiment.

- Data Analysis: Recalculate the ER in the presence of the inhibitor. A significant reduction in the ER (towards a value of 1) confirms P-gp-mediated efflux.

Step 3: In Vivo Validation

- Objective: To confirm P-gp efflux activity in a live animal model.

- Method: Conduct a pharmacokinetic study in wild-type mice with and without a P-gp inhibitor.

- Procedure:

- Administer a P-gp inhibitor (e.g., Tariquidar, 15 mg/kg, i.v.) or vehicle to the animals.

- After a predetermined time, administer the test compound (i.v. or p.o.).

- Collect blood and brain samples at multiple time points post-dosing.

- Determine the plasma and brain concentrations of the compound using a validated bioanalytical method.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the brain-to-plasma ratio (Kp) for both groups.

- Kp = (AUCbrain) / (AUCplasma), where AUC is the area under the concentration-time curve.

- A statistically significant increase in the Kp in the inhibitor-treated group compared to the control group provides in vivo evidence that the compound is a P-gp substrate.

Interpretation of Results: A compound is classified as a P-gp substrate if it demonstrates an efflux ratio > 2 in vitro, which is significantly diminished by a P-gp inhibitor, and shows a significantly increased brain penetration in vivo when co-administered with a P-gp inhibitor.

Guide 2: Assessing Tight Junction Integrity In Vitro

Problem: A novel drug delivery strategy (e.g., a nanoparticle formulation) is intended to transiently and safely modulate the BBB to improve drug delivery. You need to evaluate its potential impact on BBB integrity.

Investigation Hypothesis: The formulation may compromise BBB integrity by disrupting tight junction complexes.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol:

Step 1: Real-time Monitoring of Barrier Integrity

- Objective: To continuously and non-invasively monitor the integrity of the endothelial cell monolayer.

- Method: Use an Electrical Cell-substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) system or a voltohmmeter to measure Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER).

- Procedure:

- Grow brain endothelial cells (e.g., hCMEC/D3) on gold electrode arrays or Transwell inserts designed for TEER measurement.

- Monitor TEER until it reaches a stable, high value (e.g., >150 Ω×cm² for many models), indicating a tight monolayer.

- Apply the test formulation to the apical compartment. Include a positive control (e.g., calcium-free medium to disrupt junctions) and a negative control (vehicle/blank buffer).

- Record TEER values at frequent intervals (e.g., every 15-30 minutes) for up to 24 hours.

- Data Analysis: Express TEER as a percentage of the pre-treatment value. A significant and rapid drop in TEER indicates a loss of barrier integrity.

Step 2: Assessment of Paracellular Permeability

- Objective: To functionally quantify the flux of paracellular markers across the monolayer.

- Method: Perform a permeability assay using fluorescent or radiolabeled tracers of different sizes after treatment.

- Procedure:

- After treating cells as in Step 1, add a membrane-impermeable paracellular tracer to the donor compartment (apical for A-to-B flux). Common tracers include:

- Sodium fluorescein (376 Da): For small molecule permeability.

- FITC-Dextran (4 kDa or 10 kDa): For larger molecule permeability.

- Incubate for a set time (e.g., 30-60 minutes) at 37°C.

- Sample from the acceptor compartment and measure fluorescence/radioactivity.

- After treating cells as in Step 1, add a membrane-impermeable paracellular tracer to the donor compartment (apical for A-to-B flux). Common tracers include:

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Papp for the tracer. A significant increase in Papp for the treated group compared to the negative control confirms increased paracellular leak.

Step 3: Immunofluorescence Analysis of Tight Junction Proteins

- Objective: To visually assess the morphological impact on tight junction complexes.

- Method: Use confocal microscopy to examine the localization and continuity of key tight junction proteins.

- Procedure:

- At the end of the treatment period, wash cells and fix with paraformaldehyde (e.g., 4% for 15 min).

- Permeabilize cells with Triton X-100 (e.g., 0.1% for 10 min) and block with serum (e.g., 5% BSA for 1 hour).

- Incubate with primary antibodies against tight junction proteins (e.g., anti-claudin-5, anti-occludin, anti-ZO-1) overnight at 4°C.

- Incubate with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488, 568) for 1 hour at room temperature. Include a nuclear stain (e.g., DAPI).

- Image using a confocal microscope.

- Data Analysis: In an intact barrier, ZO-1, claudin-5, and occludin appear as continuous, sharply defined bands at the cell borders. Disruption is characterized by fragmentation, discontinuity, or internalization of these signals.

Interpretation of Results: A formulation that causes a drop in TEER, an increase in paracellular tracer flux, and discontinuous tight junction immunostaining is likely disrupting BBB integrity. The combination of functional and morphological data provides a comprehensive assessment.

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Common Tracer Molecules for Assessing BBB Paracellular Permeability

| Tracer Molecule | Molecular Weight (Da) | Key Properties | Application in BBB Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Fluorescein | 376 | Hydrophilic, fluorescent | A standard small molecule tracer to assess minor changes in paracellular permeability [10]. |

| FITC-Dextran 4k | 4,000 | Hydrophilic, fluorescently labeled polysaccharide | Used to model the passage of small biologics and assess more significant barrier disruption [10]. |

| FITC-Dextran 10k | 10,000 | Hydrophilic, fluorescently labeled polysaccharide | A larger tracer to probe major barrier breakdown, relevant for larger therapeutic molecules [10]. |

| Evans Blue | 961 | Binds serum albumin, forming a ~68 kDa complex | A classic in vivo tracer; the albumin complex is used to visualize and quantify gross leakage of proteins [10]. |

| Sucrose | 342 | Radiolabeled (e.g., 14C-sucrose), hydrophilic | A non-metabolized small molecule tracer providing high sensitivity in quantitative permeability studies [10]. |

Table 2: Key Efflux Transporters at the BBB and Their Substrates

| Transporter | Primary Location | Representative Substrates (Therapeutics) | Impact on Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-glycoprotein (P-gp/ABCB1) | Luminal membrane | Chemotherapeutics (doxorubicin, paclitaxel), HIV protease inhibitors (ritonavir), antibiotics (erythromycin) [13] [14] | Major obstacle for a wide range of small molecule drugs; contributes to multidrug resistance in brain tumors and other CNS diseases. |

| Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP/ABCG2) | Luminal membrane | Chemotherapeutics (mitoxantrone, topotecan), tyrosine kinase inhibitors (imatinib) [4] | Often works in concert with P-gp; limits penetration of many targeted therapy agents. |

| Multidrug Resistance-Associated Proteins (MRPs/ABCC family) | Luminal / Basolateral membranes | Anticonvulsants (phenytoin), methotrexate, conjugated organic anions [4] | Contributes to the efflux of anionic drugs and drug conjugates, impacting treatment of epilepsy and cancer. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Tight Junction Regulation Pathway

In Vitro BBB Model Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating BBB Physiological Barriers

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| hCMEC/D3 Cell Line | A widely used, well-characterized human immortalized brain endothelial cell line for in vitro BBB models [4]. | Represents many key BBB properties but requires induction for high TEER; lower baseline TEER than in vivo. |

| MDCK-MDR1 Cell Line | Canine kidney cells overexpressing human P-gp; a standard model for high-throughput efflux transporter studies [13]. | Not of brain origin; used primarily for transporter interaction screening rather than full BBB mimicry. |

| Claudin-5 Antibody | Immunodetection of the critical tight junction protein for assessing junctional integrity via IF or WB [10]. | Specificity is critical; results should be interpreted alongside functional data (TEER, permeability). |

| P-gp Inhibitors (e.g., Zosuquidar, Tariquidar) | Selective pharmacological blockers used to confirm P-gp substrate status in transport and in vivo studies [13]. | Concentration must be optimized to avoid non-specific effects; verify selectivity for P-gp over other transporters. |

| Paracellular Tracers (e.g., FITC-Dextran 4k) | Hydrophilic, size-defined molecules used to quantify functional paracellular permeability [10]. | A panel of tracers of different sizes (e.g., 4k, 10k, 70k Da) can provide information on the size selectivity of barrier opening. |

| Transwell Inserts | Permeable supports for growing endothelial cell monolayers and performing transport assays. | Pore size (e.g., 0.4 µm, 1.0 µm) and membrane material (e.g., polyester, polycarbonate) can influence cell growth and assay outcomes. |

FAQ: Blood-Brain Barrier Fundamentals and Dysfunction

Q1: What is the primary function of the BBB, and why is it a major challenge for drug development in neurodegenerative diseases?

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective semi-permeable border that protects the central nervous system (CNS). It maintains brain homeostasis by preventing harmful substances in the blood from entering the brain while regulating the transport of nutrients [4] [16]. Its structure, composed of brain microvascular endothelial cells connected by tight junctions, along with pericytes, astrocytes, and a basement membrane, creates a formidable physical and metabolic barrier [4]. This protective function becomes a major therapeutic challenge because it blocks over 98% of small-molecule drugs and nearly 100% of large-molecule therapeutics, such as proteins, antibodies, and gene therapies, from reaching the brain in effective concentrations [15] [4] [16].

Q2: How does BBB dysfunction contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease?

BBB dysfunction plays a key role in Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathogenesis through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Structurally, the barrier deteriorates, particularly in the hippocampus, with this degradation being more pronounced in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) than in healthy controls [17]. Key molecular changes include reduced levels of LRP-1 (a transporter that clears amyloid-β from the brain) and increased levels of RAGE (a receptor that facilitates amyloid-β influx into the brain), leading to impaired amyloid-β clearance and accumulation [17]. This dysfunction triggers neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, which can further enhance the activity of β- and γ-secretases, increasing amyloid-β production and creating a vicious cycle of pathology and barrier impairment [17]. Recent CSF proteomic research has even identified a specific AD subtype primarily driven by BBB dysfunction, emphasizing its central role in the disease [17].

Q3: What are the common pathways of BBB dysfunction across Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS?

While each disease has unique features, common pathways of BBB dysfunction link these neurodegenerative pathologies. Neuroinflammation is a universal hallmark, characterized by the activation of endothelial cells and the release of cytokines that compromise barrier integrity [15] [4]. Impaired clearance of toxic proteins—such as amyloid-β in AD, α-synuclein in PD, and SOD1 in ALS—is another shared mechanism, often involving dysregulation of specific transporters at the BBB [15] [17]. Furthermore, a loss of tight junction integrity leads to increased paracellular permeability across these diseases [4]. The choroid plexus, which forms the blood-CSF barrier, also shows dysfunction in AD and likely in other neurodegenerative conditions, contributing to altered CSF production and impaired immune surveillance [18] [17].

FAQ: Advanced Models and Diagnostic Tools

Q4: What novel biomarkers are emerging for detecting BBB dysfunction in patients?

Research is moving beyond classical amyloid and tau biomarkers to identify blood-based biomarkers (BBMs) related to brain barrier failure. Promising candidates include [17]:

- Neurofilament Light (NfL): Associated with neuroinflammation, demyelination, and axonal degradation.

- Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP): An indicator of neuroinflammation and astrocyte activation.

- Transactive Response DNA-binding Protein 43 (TDP-43): Implicated in tau-independent neurodegeneration.

- Complement Component 3 (C3): Involved in neuroinflammatory pathways.

Advanced MRI techniques can also measure the volume and structural integrity of the choroid plexus. Studies have found that an enlarged choroid plexus volume and reduced structural integrity are correlated with higher levels of p-tau181, NfL, and GFAP, suggesting these imaging measures can serve as non-invasive proxies for BBB and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction even in early-stage AD [17].

Q5: What in vivo and in vitro models are best for studying BBB dysfunction and drug penetration?

The choice of model depends on the specific research question. The table below summarizes key models and their applications.

Table 1: Experimental Models for Studying BBB Dysfunction and Drug Penetration

| Model Type | Key Features | Best Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Animal Models | Provides a full physiological context, including all cell types of the neurovascular unit and blood flow [4]. | Studying complex disease pathogenesis, whole-body pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of novel delivery systems [19]. | Interspecies differences in BBB biology; ethical and cost concerns. |

| In Vitro Static Models (e.g., Transwell assays) | Cultured brain endothelial cells on a permeable filter. Low-cost, high-throughput screening of permeability [4]. | Initial assessment of passive diffusion or transporter-mediated uptake; mechanistic studies. | Lack of fluid flow and crucial cellular interactions; often overestimates permeability. |

| Advanced In Vitro Models (e.g., microfluidic "BBB-on-a-chip") | Incorporates fluid shear stress and co-culture with pericytes and astrocytes for a more physiologically relevant barrier [4]. | Detailed study of barrier function and cell-cell interactions under controlled conditions. | More complex and expensive to set up than static models. |

| AI-Powered In Vivo Screening (e.g., Manifold Bio's mDesign) | Uses barcoded protein libraries screened in live animals; AI learns from real physiological data [19]. | High-throughput, predictive screening of thousands of potential "brain shuttle" constructs in a physiological environment. | Cutting-edge technology, not yet widely available; requires specialized expertise. |

FAQ: Therapeutic Strategies and Troubleshooting

Q6: What are the most promising strategies for delivering therapeutics across the BBB?

Strategies can be classified as passive or active targeting, with active and disruption-based methods showing the most promise for large molecules.

Table 2: Promising Strategies for Delivering Therapeutics Across the BBB

| Strategy | Mechanism | Therapeutic Payload | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT) | Uses ligands (antibodies, peptides) to bind receptors (TfR, insulin receptor) on BBB, hijacking natural transport [15] [20] [4]. | Antibodies, proteins, oligonucleotides [20] [16]. | Clinical/Commercial (e.g., JCR Pharma's Hunter syndrome drug) [20]. |

| Biomimetic Nanoparticles | Synthetic nanoparticles disguised with natural membranes (e.g., RBCs, leukocytes, stem cells) to evade immune system and target inflammation [21] [22]. | Small molecule drugs, nucleic acids, proteins. | Preclinical research (e.g., platelet膜纳米颗粒 for stroke) [21]. |

| Cell-Mediated "Trojan Horse" | Uses living cells (e.g., immune cells) that naturally traverse the BBB to carry therapeutic cargo [15] [18]. | Various, including neurotrophic factors. | Preclinical research. |

| Focused Ultrasound (FUS) | Temporarily and reversibly disrupts BBB tight junctions using ultrasound waves, often with microbubbles [15]. | Antibodies, chemotherapy. | Clinical trials. |

| Viral Vectors | Engineered viruses (e.g., AAV) modified to target BBB receptors for gene delivery [15] [20]. | Gene therapies, CRISPR-Cas9 [15]. | Preclinical and early clinical trials. |

Q7: Our therapeutic antibody shows excellent target engagement in vitro but no efficacy in vivo. What could be wrong?

This common issue almost always points to a BBB delivery failure. Potential solutions and investigations include:

- Quantify Brain Uptake: Measure the actual concentration of the antibody in the brain parenchyma after systemic administration. It is likely extremely low (<0.1% of injected dose) [20].

- Employ a "Brain Shuttle": Re-engineer the antibody by fusing it to a ligand that binds a highly expressed BBB receptor, such as the transferrin receptor (TfR). This engages receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) to actively ferry the antibody across the endothelial cells. Roche's Trontinemab, a TfR-targeting anti-amyloid antibody, showed 3-fold greater plaque clearance efficiency at one-fifth the dose of its unmodified counterpart [20].

- Leverage AI for Design: Consider using advanced platforms like Manifold Bio's mDesign, which uses in vivo screening and AI to design highly effective BBB-shuttling components, optimizing for real-world physiological conditions [19].

- Check for Efflux: While more common for small molecules, ensure your antibody is not being actively exported by efflux transporters at the BBB.

Q8: We are using nanoparticle carriers, but they are being cleared by the immune system before reaching the brain. How can we improve their circulation time?

This is a key challenge in nanomedicine. The most effective strategy is to use biomimetic camouflage.

- PEGylation: Coating nanoparticles with polyethylene glycol (PEG) creates a "stealth" layer that reduces protein adsorption and recognition by immune cells, prolonging circulation [21] [22].

- Cell Membrane Coating: Wrapping nanoparticles in membranes derived from red blood cells (RBCs) is highly effective. The RBC membrane displays "self-markers" like CD47, which signals immune cells to avoid phagocytosis, significantly reducing clearance [21] [22]. Other membranes, such as those from leukocytes or platelets, can also provide immune evasion while adding active targeting capabilities to inflamed brain endothelium [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for BBB and Neurodegenerative Disease Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BBB In Vitro Model Kits | To establish a human-relevant barrier for permeability and mechanistic studies. | Commercially available primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes. Microfluidic "BBB-on-chip" kits are also emerging. |

| Ligands for RMT | To functionalize therapeutics or carriers for active BBB crossing. | Transferrin Receptor (TfR) binders: Monoclonal antibodies or binding peptides. RVG29 peptide: Binds neuronal acetylcholine receptor for neuronal targeting [21] [22]. Angiopep-2: Targets LRP1 receptor on BBB [22]. |

| Biomimetic Coating Materials | To create "stealth" and targeted nanoparticles with improved pharmacokinetics. | PEG-lipids for PEGylation [22]. Isolated cell membranes from RBCs, leukocytes, or platelets [21] [22]. Recombinant ApoE for lipoprotein-mimicking nanoparticles targeting BBB receptors [22]. |

| Blood-Based Biomarker Assays | For non-invasive diagnosis and monitoring of BBB dysfunction and neurodegeneration. | Commercial immunoassays (ELISA, SIMOA) for p-tau181, p-tau217, GFAP, NfL. FDA-cleared blood tests like Lumipulse G (p-tau217/Aβ42 ratio) [17]. |

| Viral Vectors for CNS Gene Delivery | To deliver genetic material (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9, ASOs, therapeutic genes) to the brain. | Adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes with tropism for the CNS (e.g., AAV9, AAV-PHP.eB). Engineered AAVs with capsids modified to enhance BBB transit (e.g., via TfR targeting) [15] [20]. |

Visualizing Key Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate core concepts and experimental workflows in BBB research.

Diagram 1: BBB Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration

This diagram summarizes the key pathological mechanisms of BBB breakdown in diseases like Alzheimer's.

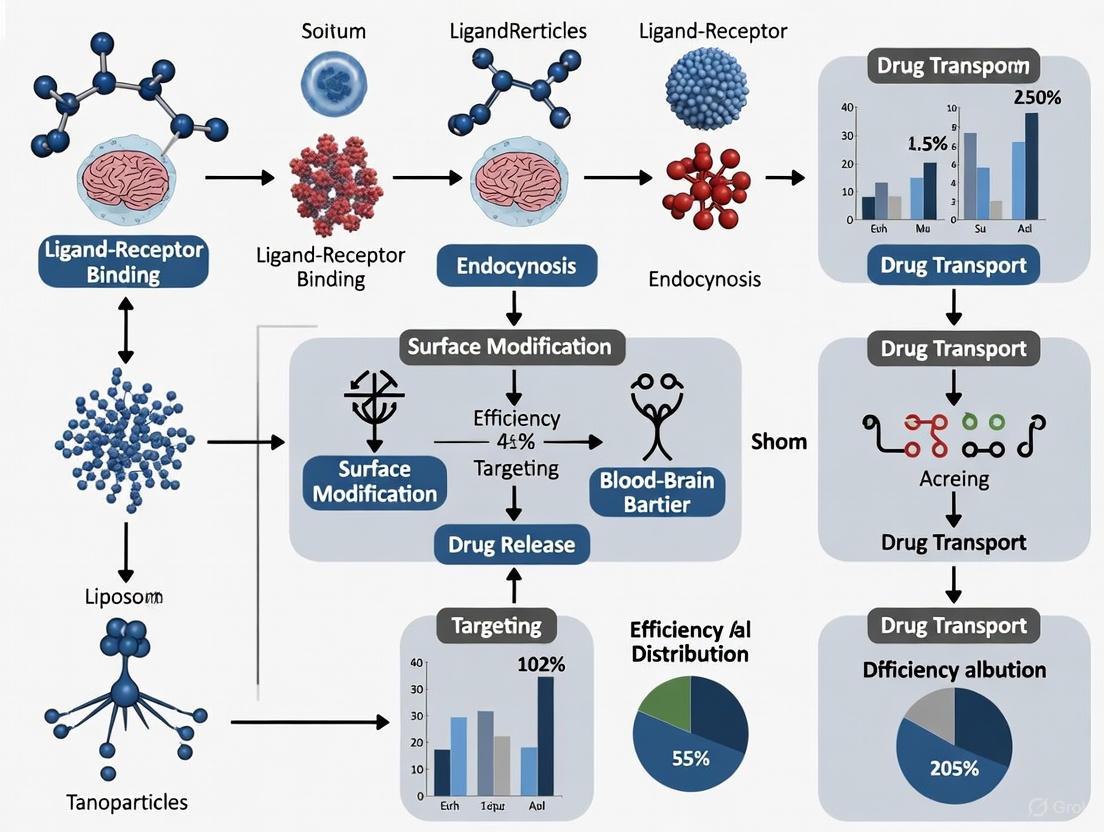

Diagram 2: Drug Delivery Strategies Workflow

This flowchart outlines the decision-making process for selecting a BBB drug delivery strategy based on the therapeutic payload.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary natural transport mechanisms for crossing the BBB that can be exploited for drug delivery?

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) has several innate transport pathways that can be co-opted for drug delivery [3] [4]:

- Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT): This mechanism allows large molecules to cross the BBB by binding to specific receptors on the endothelial cell surface, such as the transferrin receptor or insulin receptor. The molecule is engulfed in a vesicle and transported across the cell [15] [23].

- Carrier-Mediated Transport (CMT): This system uses protein carriers to shuttle essential small molecules, such as glucose and amino acids, across the BBB. Drugs structurally similar to these nutrients can use these transporters [4] [23].

- Adsorptive-Mediated Transcytosis (AMT): This is a non-specific charge-based interaction where positively charged molecules (cationic proteins or cell-penetrating peptides) interact with the negatively charged cell membrane, triggering vesicle formation and transport across the endothelium [4].

FAQ 2: My engineered nanoparticles show good binding to BBB receptors in vitro but poor brain uptake in vivo. What could be the issue?

This common problem can arise from several factors [15] [24]:

- Protein Corona Formation: Upon intravenous administration, nanoparticles can be coated with serum proteins, which may mask the targeting ligands and prevent receptor recognition.

- Rapid Clearance by the Reticuloendothelial System (RES): Nanoparticles may be sequestered by the liver and spleen before reaching the brain.

- Insufficient Ligand Density or Binding Affinity: The number of targeting molecules on the nanoparticle surface or their strength of binding may be insufficient to compete with natural ligands.

- Off-Target Binding: The targeting ligand may bind to its receptor on other tissues, reducing the dose available for BBB crossing.

FAQ 3: How can I determine if my drug is a substrate for efflux pumps like P-glycoprotein (P-gp)?

Several experimental approaches can identify efflux pump substrates [25] [23]:

- In Vitro Transport Assays: Use cultured brain endothelial cell monolayers. Measure the bidirectional permeability (A-to-B vs. B-to-A) of your drug. A significantly higher B-to-A flux suggests active efflux.

- Inhibition Studies: Co-incubate the drug with a known efflux pump inhibitor (e.g., verapamil for P-gp). A subsequent increase in A-to-B permeability or brain uptake confirms involvement of that transporter.

- In Vivo Studies in Knockout Animals: Compare the brain concentration of the drug in wild-type mice versus mice lacking the specific efflux transporter gene (e.g., Mdr1a/b-/- for P-gp). A higher concentration in the knockout animals indicates the drug is an efflux substrate.

FAQ 4: What are the key considerations when choosing a ligand for receptor-mediated transcytosis?

Selecting an appropriate ligand is critical for success [15] [11]:

- Receptor Specificity and Expression: The receptor should be highly and exclusively expressed on the BBB endothelium to minimize off-target effects.

- Ligand Affinity: The ligand should have high affinity for the receptor, but not so high that it prevents the release of the cargo on the abluminal (brain) side.

- Immunogenicity: Antibody-based ligands may trigger immune responses. Smaller peptide ligands or antibody fragments (e.g., scFv) are often less immunogenic.

- Cargo Capacity: The receptor-ligand system must be able to internalize and transport the size and type of your drug cargo (e.g., small molecule, protein, or nanoparticle).

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Transcytosis Efficiency Despite High Cellular Uptake

Symptoms*: Your targeted delivery system shows good internalization into brain endothelial cells in vitro, but the cargo fails to appear in the brain parenchyma in vivo. The cargo seems trapped within the cells.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Lysosomal Trapping/Degradation | - Use lysotracker dyes to check co-localization with lysosomes.- Measure cargo integrity after cellular uptake. | - Incorporate endosomolytic peptides or polymers (e.g., pH-sensitive histidine-rich peptides) to promote endosomal escape [11].- Use ligands that traffic through non-degradative pathways. |

| Inefficient Vesicle Trafficking | - Use live-cell imaging to track vesicle movement.- Inhibit key trafficking proteins (e.g., with dynamin inhibitors) and measure the effect on transcytosis. | - Optimize ligand properties (size, valency) to steer vesicle fate towards transcytosis rather than recycling [3]. |

| Ligand-Receptor Complex Does Not Dissociate | - Use surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to measure binding kinetics at different pH levels.- Check if the ligand is recycled back to the luminal surface. | - Engineer ligands with pH-sensitive binding that release the receptor in the slightly more acidic endosomal environment [15]. |

Problem: Nanoparticle Toxicity and Immunogenicity

Symptoms*: In vivo experiments show signs of inflammation, activation of immune cells, or toxicity in the liver and spleen.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Material Biocompatibility | - Test different nanoparticle materials for in vitro cell viability (MTT assay).- Check for complement activation in serum. | - Switch to biodegradable and biocompatible materials (e.g., PLGA, lipids, chitosan) [14] [24].- Use PEGylation to create a "stealth" coating and reduce immune recognition. |

| Ligand-Induced Immune Response | - Screen for anti-ligand antibodies in serum after repeated administration.- Measure cytokine levels (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6). | - Use humanized antibodies or fully human ligands to reduce immunogenicity.- Consider using small peptide ligands instead of full antibodies. |

| Oxidative Stress | - Measure reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in treated cells.- Check markers of oxidative stress in tissues (e.g., lipid peroxidation). | - Co-incorporate antioxidants (e.g., curcumin, resveratrol) into the nanoparticle formulation [14]. |

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Key Natural Transport Pathways at the BBB

| Transport Mechanism | Physiological Function | Engineered Ligand/Targeting Moelty | Typical Payload Size | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT) | Uptake of large proteins (e.g., insulin, transferrin). | Anti-TfR antibody, Angiopep-2 (targeting LRP1), RI7217 (targeting TfR). | Antibodies, nanoparticles, proteins. | Potential competition with endogenous ligands; risk of saturating natural pathways [15] [3]. |

| Carrier-Mediated Transport (CMT) | Transport of essential nutrients (e.g., glucose, amino acids). | Levodopa (via LAT1), modified nucleosides. | Small molecules (< 500 Da). | Highly specific to substrate structure; limited to small molecules [25] [23]. |

| Adsorptive-Mediated Transcytosis (AMT) | Not a natural physiological pathway for specific molecules. | Cationic proteins (e.g., albumin), cell-penetrating peptides (e.g., TAT). | Proteins, nanoparticles, nucleic acids. | Low specificity; potential cytotoxicity due to non-specific membrane interaction [4]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Nanocarrier Platforms for Exploiting Natural Transport

| Nanocarrier Type | Material Examples | Compatible Transport Mechanisms | Key Advantages | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid-Based | Liposomes, Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs), Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs). | RMT, AMT. | High biocompatibility and biodegradability; high drug loading capacity [4] [24]. | Potential stability issues in circulation; batch-to-batch variability. |

| Polymeric | PLGA, Chitosan, PEG. | RMT, AMT. | Controlled release kinetics; surface easily functionalized [14]. | Risk of polymer-associated toxicity; degradation products must be non-toxic. |

| Biological | Exosomes, Albumin Nanoparticles. | Innate RMT (if derived from specific cells). | Low immunogenicity; natural targeting capabilities [15] [6]. | Difficulties in large-scale production and drug loading. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Assessment of RMT Using a BBB Co-culture Model

Objective*: To evaluate the transcytosis efficiency and pathway of a ligand-decorated nanoparticle across a simulated BBB.

Materials*:

- Cell Culture: Primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs), pericytes, and astrocytes.

- Transwell Plates: (e.g., 12-well, 3.0 µm pore size).

- Targeted Nanoparticles: Your ligand-decorated nanoparticles and non-targeted controls.

- Inhibitors: Chlorpromazine (clathrin-mediated endocytosis inhibitor), Filipin (caveolae-mediated endocytosis inhibitor), excess free ligand (for competitive inhibition).

Procedure*:

- Model Establishment: Seed HBMECs on the apical side of the Transwell insert. Culture pericytes and astrocytes on the basolateral side to create a neurovascular unit co-culture. Allow the model to mature for 5-7 days, monitoring Trans-Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) until it exceeds 150 Ω·cm² [23].

- Transport Assay:

- a. Replace the medium in both compartments with fresh pre-warmed buffer.

- b. Add your nanoparticle suspension to the apical (donor) compartment.

- c. At predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 120 min), collect small samples from the basolateral (acceptor) compartment and replace with fresh buffer.

- d. Measure the concentration of nanoparticles or their cargo in the samples using a relevant method (e.g., fluorescence, HPLC).

- Inhibition Studies: Pre-incubate the HBMECs with the various inhibitors for 30-60 minutes before repeating step 2. A significant reduction in transport with a specific inhibitor indicates the primary pathway used.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) and the percentage of transported dose. Compare targeted vs. non-targeted and inhibited vs. non-inhibited conditions.

Protocol 2: Validating Efflux Pump Interaction

Objective*: To determine if a new chemical entity (NCE) is a substrate for P-glycoprotein (P-gp).

Materials*:

- In Vitro System: MDCKII or LLC-PK1 cell lines overexpressing human MDR1 (P-gp).

- Test Compound: Your NCE, with a known P-gp substrate (e.g., digoxin) as a positive control.

- Inhibitor: A specific P-gp inhibitor like zosuquidar (LY335979) or verapamil.

- LC-MS/MS or other sensitive analytical equipment for compound quantification.

Procedure*:

- Cell Seeding: Seed MDR1-transfected cells on Transwell filters and culture until a confluent monolayer with high TEER is formed.

- Bidirectional Transport:

- a. A-to-B Direction: Add the NCE to the apical compartment and measure its appearance in the basolateral compartment over time.

- b. B-to-A Direction: Add the NCE to the basolateral compartment and measure its appearance in the apical compartment over time.

- Inhibition: Repeat the bidirectional transport assay in the presence of a P-gp inhibitor added to both compartments.

- Data Analysis:

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT) Pathway

Diagram 2: Drug Delivery System Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Natural Transport Mechanisms

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Supplier / Catalog (for reference) |

|---|---|---|

| hCMEC/D3 Cell Line | Immortalized human brain endothelial cell line for in vitro BBB models. | Merck (formerly Sigma-Aldrich) |

| Anti-Human TfR Antibody | Ligand for targeting the Transferrin Receptor (TfR) in RMT studies. | BioLegend (clone #289108) or R&D Systems |

| Angiopep-2 Peptide | A peptide ligand that targets the LRP1 receptor on the BBB. | Tocris Bioscience (Cat. # 7313) or custom peptide synthesis companies. |

| P-glycoprotein (P-gp) Inhibitors (e.g., Zosuquidar, Verapamil) | To chemically inhibit P-gp efflux activity in transport assays. | Tocris Bioscience (Zosuquidar, Cat. # 4453) |

| MDCKII-MDR1 Cells | Canine kidney cells overexpressing human P-gp for standardized efflux assays. | Netherlands Cancer Institute (NKI) or commercial providers. |

| Dylight 650 NHS Ester | Fluorescent dye for labeling antibodies, peptides, or nanoparticles for tracking. | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| CLIP-tag / SNAP-tag Technology | Enzyme-based protein labeling systems for site-specifically labeling targeting ligands. | New England Biolabs (NEB) |

| Poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) | Biodegradable polymer for fabricating nanoparticles for drug encapsulation. | Lactel Absorbable Polymers (DURECT Corporation) |

| Lipoid S100 | Phosphatidylcholine from soybean lecithin for formulating liposomes and lipid nanoparticles. | Lipoid GmbH |

Breaking Through: A Toolkit of Advanced BBB Crossing Technologies

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Low Brain Delivery Efficiency

Problem: Your RMT-targeting construct shows insufficient brain accumulation despite high plasma concentration.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low RMT receptor affinity | Perform Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) to measure binding affinity (KD). Compare to positive controls (e.g., TfR antibody with KD ~1-10 nM) [26]. | Affinity maturation via phage display or yeast display libraries. Optimize binding valency (e.g., bivalent vs. monovalent) [26] [27]. |

| Lysosomal degradation | Co-localization studies using immunofluorescence staining for LAMP1/LAMP2 (lysosomal markers) in brain endothelial cells [28]. | Engineer pH-dependent binding to dissociate from the receptor in early endosomes, promoting transcytosis over recycling/degradation [28] [26]. |

| High off-target binding | Quantitative biodistribution study in peripheral tissues (e.g., liver, spleen) [26]. | Select brain-enriched RMT targets (e.g., CD98hc, Basigin). Use antibodies with lower peripheral organ uptake profiles [26]. |

| Inefficient endocytosis | Measure cellular internalization kinetics using flow cytometry or confocal microscopy in hCMEC/D3 cells (human brain endothelial cell line) [28]. | Screen multiple antibody clones against different epitopes on the RMT receptor to identify those promoting efficient clathrin-mediated endocytosis [28]. |

Troubleshooting Safety and Toxicity Issues

Problem: Observed peripheral toxicity or unexpected pharmacological effects during in vivo studies.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| TfR-mediated erythrocyte depletion | Complete blood count (CBC) analysis, particularly monitoring reticulocyte counts [26]. | Engineer anti-TfR antibodies with reduced FcγR binding (e.g., aglycosylated Fc) to minimize effector function on red blood cells [26]. |

| IR/IGF1R-mediated metabolic effects | Frequent blood glucose monitoring during and after antibody infusion [26]. | Use lower affinity anti-IR antibodies (ED50 ~0.25-0.5 nM) and administer with dextrose supplementation [26]. |

| Target-mediated peripheral drug disposition | Compare plasma pharmacokinetics in wild-type vs. receptor-knockout mice [26]. | Optimize dosing regimen (e.g., higher dose, less frequent administration) to saturate peripheral sinks. |

| Immune activation (e.g., ARIA in AD) | MRI monitoring for amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) [27]. | Optimize antibody dose and infusion protocol; consider pre-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages and disadvantages of TfR, CD98hc, and IGF1R as RMT targets?

- TfR (Transferrin Receptor):

- Advantages: High expression on BBB; well-validated with multiple clinical candidates (e.g., Denali's TV platform, JR-141) [26] [27].

- Disadvantages: High peripheral expression (e.g., liver, spleen) causing off-target effects; potential for reticulocyte depletion; expression may decrease in aged or diseased brain [26].

- CD98hc:

- Advantages: Identified via omics as highly expressed on mouse BECs; antibodies show significant brain enrichment [26].

- Disadvantages: Less clinical validation compared to TfR; broader biological functions may complicate safety profile.

- IGF1R (Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor):

- Advantages: Slightly more abundant BBB expression compared to TfR; successful application in bispecific antibodies (e.g., SAR446159/ABL301 for Parkinson's) [26] [29].

- Disadvantages: Potential for metabolic side effects similar to IR, though engineered VHHs (e.g., IGF1R4) can achieve dose-dependent responses [26].

Q2: How do I validate successful transcytosis versus simple endothelial cell binding and uptake?

A multi-step validation workflow is crucial [28] [26]:

- In vitro BBB models: Use a validated transwell system with human brain endothelial cells (e.g., hCMEC/D3). Measure apparent permeability (Papp) and compare to negative controls. Inhibit key RMT pathways (e.g., with receptor-blocking antibodies) to confirm specificity.

- Cellular trafficking studies: Perform immunofluorescence co-localization with endosomal (EEA1, RAB5), recycling (RAB11), and lysosomal (LAMP1) markers to track the intracellular journey.

- In vivo brain uptake measurement: After intravenous injection in mice, calculate the %Injected Dose per gram of brain (%ID/g) at multiple time points. A value significantly higher than a non-targeting control antibody (e.g., >0.5-1% ID/g) indicates successful transport.

- Perfusion: Perfuse animals with buffer prior to brain collection to remove blood pool antibody, ensuring measurement of parenchymal delivery rather than vascular binding.

Q3: What is the impact of binding affinity on RMT efficiency? Is higher affinity always better?

No, higher affinity is not always better. The relationship between affinity and brain uptake often follows a "sweet spot" [26]:

- Very High Affinity: Can cause the "binding site barrier" effect, where the antibody is sequestered on the luminal side of the BBB and does not release into the brain parenchyma.

- Very Low Affinity: Fails to efficiently engage the receptor for endocytosis.

- Optimal Affinity: Typically in the low nanomolar range (e.g., 1-10 nM), allowing for efficient receptor engagement, internalization, and subsequent release within the endosomal system or at the abluminal side. Affinity must be optimized for each specific RMT target and antibody format.

Q4: Which antibody formats are most suitable for RMT-based delivery?

The choice depends on the therapeutic cargo and desired pharmacokinetics [26]:

- Full-length IgGs: Suitable for fusing to protein therapeutics (e.g., enzyme replacement therapies like valanafusp alpha). The Fc domain can be engineered to reduce effector function.

- Single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) and VHHs (nanobodies): Smaller size may improve tissue penetration. Often used as the targeting moiety in bispecific antibodies (e.g., the IGF1R-targeting scFv in SAR446159) [29].

- Bispecific Antibodies: One arm targets the RMT receptor (e.g., TfR, IGF1R), while the other arm engages the therapeutic target in the brain (e.g., α-synuclein, BACE1) [27] [29]. This is the most common format for delivering therapeutic antibodies across the BBB.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Data for Featured RMT Targets and Reagents

| RMT Target | Representative Agent / Format | Key Quantitative Metric | Value / Affinity | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TfR | Pabinafusp alfa (JR-141) | Clinical Outcome | Approved in Japan for MPS-II (Hunter syndrome) | [26] |

| TfR | Denali TfR Transport Vehicle (TV) | Brain Uptake (%ID/g) | High concentration and broad distribution in rodent and NHP brains | [26] |

| IR | AGT-181 (Valanafusp alpha) | Binding Affinity (ED50) | 0.25 - 0.5 nM | [26] |

| IR | AGT-181 | Clinical Dosing | 0.3 - 6 mg/kg in trials (with nutritional supplements) | [26] |

| IGF1R | VHH IGF1R4 | Functional Response | Dose-dependent, pharmacologically relevant response to galanin | [26] |

| IGF1R | SAR446159 (1E4 + IGF1R scFv) | Binding Affinity (to α-Syn PFFs) | Sub-picomolar (approaching SPR limit) | [29] |

| General BBB | Typical Antibody | Brain Uptake (%ID/g) | ~0.1 - 0.5% | [29] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RMT Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| hCMEC/D3 Cell Line | An immortalized human brain endothelial cell line for in vitro BBB models and transcytosis assays. | Requires specific culture conditions and coating (collagen I & fibronectin). Can form relatively tight monolayers. |

| Anti-TfR Antibodies (various clones) | To target the transferrin receptor for RMT. Used as positive controls or building blocks for bispecifics. | Clone selection is critical; different clones have vastly different transcytosis capabilities and potential for toxicity. |

| Anti-IGF1R VHHs (e.g., IGF1R4) | Single-domain antibodies for targeting IGF1R. Can be engineered into bispecific formats. | Offer potential for high brain uptake and reduced side effects compared to some anti-TfR approaches. |

| Anti-CD98hc Antibodies | To target the CD98 heavy chain, an emerging RMT target identified via omics. | Show significant brain enrichment in preclinical models; useful for exploring novel pathways. |

| Recombinant α-Syn Preformed Fibrils (PFFs) | For in vitro and in vivo modeling of synucleinopathies when testing therapeutics like SAR446159. | Essential for testing the functional efficacy of delivered therapeutics in disease-relevant models. |

| LAMP1 / LAMP2 Antibodies | Lysosomal markers for immunofluorescence to assess if RMT cargo is being degraded vs. transcytosed. | Crucial for troubleshooting low brain delivery efficiency. |

| RAB5 / RAB11 Antibodies | Markers for early endosomes and recycling endosomes, respectively. Used to track intracellular trafficking. | Helps map the intracellular route of the RMT cargo and identify trafficking bottlenecks. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol:In VitroTranscytosis Assay Using hCMEC/D3 Cells

This protocol measures the ability of an RMT-targeting antibody to cross a monolayer of human brain endothelial cells [28] [26].

Materials:

- hCMEC/D3 cells (passage 25-35)

- Collagen I (rat tail), fibronectin

- EGM-2 MV culture medium

- 12-well or 24-well transwell plates (polycarbonate membranes, pore size)

- Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS)

- Test articles: RMT-targeting antibody, isotype control antibody

- Anti-human IgG antibody for ELISA quantification

Procedure:

- Coating: Coat transwell inserts with collagen I (150 µg/mL) and fibronectin (10 µg/mL) in PBS for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Cell Seeding: Trypsinize hCMEC/D3 cells and seed onto the apical (upper) chamber of the coated inserts at a density of 50,000-100,000 cells/cm². Maintain the cells for 5-7 days, changing the medium every 2 days, to form a confluent, polarized monolayer.

- Integrity Check: Measure the Trans-Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) using a volt-ohm meter. Accept only monolayers with TEER >30 Ω·cm² for the assay.

- Assay Setup: Warm HBSS to 37°C. Replace the medium in both apical and basolateral chambers with pre-warmed HBSS. Incubate for 30 min.

- Dosing: Add the test antibody (e.g., 10 µg/mL) to the apical chamber (donor compartment). The basolateral chamber serves as the receiver (acceptor compartment).

- Incubation: Place the plate in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO₂. Gently shake the plate on an orbital shaker (50-100 rpm).

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 120 min), remove a sample (e.g., 100 µL) from the basolateral chamber. Replace with an equal volume of fresh pre-warmed HBSS.

- Quantification: Determine the concentration of the test antibody in the basolateral samples using a specific ELISA (e.g., using an anti-human IgG capture antibody).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Apparent Permeability (Papp) using the formula: Papp (cm/s) = (dQ/dt) / (A * C₀) where dQ/dt is the transport rate (µg/s), A is the surface area of the membrane (cm²), and C₀ is the initial concentration in the donor chamber (µg/mL).

Protocol: Validating Brain Uptake and PharmacodynamicsIn Vivo

This protocol outlines the key steps to validate the in vivo efficacy of an RMT-delivered therapeutic, such as an α-synuclein aggregate-binding antibody [29].

Materials:

- Wild-type or disease model mice (e.g., α-syn PFF-injected mice)

- Test articles: RMT-bispecific antibody (e.g., SAR446159), non-targeting control antibody

- Saline for injection

- Heparinized capillary tubes and/or EDTA-coated tubes for blood collection

- Perfusion pump and PBS

- Tissue homogenizer

Procedure:

- Dosing: Administer a single intravenous bolus injection of the test antibody (typical dose: 5-30 mg/kg) via the tail vein. Include a group injected with a non-targeting control antibody.

- Blood Collection: At specified time points post-injection (e.g., 5 min, 1h, 6h, 24h), collect blood samples via retro-orbital bleeding or cardiac puncture. Centrifuge to obtain plasma. Store at -80°C until analysis.

- Terminal Perfusion and Tissue Collection: At the end of the study (e.g., 24h), deeply anesthetize the animals. Perfuse transcardially with 20-30 mL of ice-cold PBS to clear the brain vasculature of blood.

- Brain Harvesting: Decapitate the animal and rapidly remove the brain. Weigh the whole brain or dissect into regions of interest (e.g., cortex, striatum, midbrain). Snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen.

- Tissue Homogenization: Homogenize brain tissues in a suitable buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors) at a consistent weight/volume ratio (e.g., 1:4 w/v). Centrifuge the homogenate to obtain a clear supernatant.

- Bioanalysis:

- Antibody Concentration: Quantify the concentration of the human antibody in both plasma and brain homogenate using a specific sandwich ELISA. Calculate the %Injected Dose per gram of brain tissue (%ID/g).

- Pharmacodynamic Readout: Depending on the therapeutic target, perform additional assays on the brain homogenate. For an α-synuclein antibody like SAR446159, this could be:

- ELISA: Measure levels of specific forms of α-syn (e.g., phosphorylated, oligomeric).

- Western Blot: Analyze changes in α-syn aggregation state.

- Immunohistochemistry: Assess clearance of pathological aggregates and reduction in pathology score.

- Data Analysis: Compare brain uptake (%ID/g) and pharmacodynamic effects between the RMT-bispecific group and the control group to demonstrate target engagement and therapeutic efficacy.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: The RMT Pathway and Key Engineering Decision Points. This diagram visualizes the intracellular journey of an RMT-targeting antibody, highlighting the critical sorting decision in the early endosome that determines the success of transcytosis into the brain parenchyma versus recycling or degradation.

Diagram 2: RMT Antibody Development and Validation Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key experimental stages for developing an RMT-based therapeutic, integrating critical troubleshooting feedback loops for when experiments yield suboptimal results.

Core Design Principles for Effective BBB Shuttles

Bispecific antibody shuttles are engineered to overcome the fundamental challenge of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which restricts over 98% of small-molecule drugs and nearly 100% of large-molecule therapeutics from entering the central nervous system [15] [4]. Their design centers on harnessing endogenous transport pathways, primarily Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT), to facilitate active transport into the brain.

Table 1: Key Design Principles for Bispecific Antibody Shuttles

| Design Principle | Objective | Molecular Implementation | Rationale and Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting RMT (e.g., TfR1) | Utilize natural BBB transport mechanisms | Engineered binding domain (e.g., single-chain variable fragment) against Transferrin Receptor 1 [30] | Enables active transport across the tightly joined endothelial cells of the BBB. |

| Affinity Optimization | Balance BBB penetration and target engagement | Moderate affinity (e.g., ~100 nM) for TfR1 to facilitate release after transcytosis [30] | High TfR1 affinity can trap the antibody on vascular endothelium or neurons, reducing therapeutic availability. |

| Binding Valency | Promote efficient transport and release | Monovalent binding to TfR1 [30] | Prevents bivalent cross-linking, which leads to lysosomal degradation and reduces brain exposure. |

| pH-Sensitive Binding | Enhance release within the acidic endosome | Engineering TfR1-binding domain to lose affinity at endosomal pH (~6.0) [30] | Promotes dissociation from TfR1 during transcytosis, freeing the antibody to engage its therapeutic target in the brain parenchyma. |

| Differential Affinity | Ensure correct cellular targeting | Higher affinity for the therapeutic target (e.g., Aβ) than for TfR1 [30] | Prevents the shuttle from being "captured" by TfR1-expressing cells instead of reaching its pathological target. |

The selection of the shuttle target is critical. The Transferrin Receptor 1 (TfR1) is the most clinically validated target for this purpose due to its high expression on brain capillary endothelial cells and well-characterized transcytosis pathway [30]. A leading example is trontinemab, an investigational Brainshuttle bispecific antibody that combines an amyloid-beta-binding antibody with a TfR1 shuttle module [31] [32].

The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanism of action for a TfR1-bispecific antibody shuttle.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Development Issues

Despite a rational design, developers often encounter specific challenges. Below is a guide to diagnosing and resolving these issues.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Bispecific Antibody Shuttles

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Brain Penetration | Excessive affinity/avidity for TfR1 | Weaken TfR1-binding affinity; ensure monovalent, pH-sensitive binding [30]. |

| Incorrect TfR1 binding epitope | Screen TfR1-binding domains that do not compete with endogenous transferrin. | |

| High Peripheral Toxicity or Rapid Clearance | Uptake in TfR1-rich peripheral tissues (e.g., spleen, bone marrow) | Optimize TfR1 affinity to minimize peripheral binding while retaining brain uptake [30]. |

| Immunogenicity against the shuttle component | Implement humanization strategies and screen for pre-existing antibodies. | |

| Inefficient Target Engagement in Brain | Shuttle captured by TfR1 on neurons | Ensure therapeutic target affinity is significantly higher than TfR1 affinity [30]. |

| Instability or aggregation in CNS environment | Improve thermal and colloidal stability via formulation and protein engineering [33]. | |

| Product-Related Impurities (Aggregates, Fragments) | Inherent instability of the bispecific format | Optimize cell culture conditions and purification; use protein engineering to improve stability [33] [34]. |

| Incorrect chain pairing during expression | Utilize platform technologies like "Knobs-into-Holes" and "CrossMab" to enforce correct assembly [35]. | |

| Inconsistent In Vivo Efficacy | Limited penetration into target brain region | Consider that different shuttles may have varying distribution profiles; explore other RMT targets. |

| Animal model does not fully recapitulate human BBB biology | Validate findings in multiple, translationally relevant models. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing Brain Uptake and Target Engagement

This protocol outlines the key steps for the production and preclinical validation of a bispecific antibody shuttle, from expression to functional analysis in vivo.

Experimental Workflow: From Gene to Functional Validation

Phase 1: Molecular Construction and Expression

- Step 1.1 – Vector Design: Clone genes encoding the variable domains for the therapeutic target (e.g., Aβ) and the BBB shuttle target (e.g., TfR1) into a single mammalian expression vector. Use a system that facilitates correct heavy and light chain pairing, such as Knobs-into-Holes for the Fc region and a common light chain or CrossMab technology for the Fab arms [35] [34].

- Step 1.2 – Transfection and Expression: Transfect the construct into a mammalian cell line, typically CHO (Chinese Hamster Ovary) cells, using methods like electroporation or lipid-based transfection. Maintain cells in a bioreactor under optimized conditions (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen) to maximize yield and minimize aggregation [34] [35].

Phase 2: Downstream Purification

- Step 2.1 – Capture: Clarify the cell culture supernatant via centrifugation and filtration. Perform initial capture using Protein A affinity chromatography, which binds the antibody's Fc region [35].

- Step 2.2 – Polish: Due to the complex structure of bispecifics, a multi-step purification process is often necessary. Use additional chromatographic methods like ion exchange chromatography or hydrophobic interaction chromatography to remove product-related impurities like homodimers, fragments, and aggregates [34].

Phase 3: In Vitro Characterization

- Step 3.1 – Binding Affinity: Validate binding kinetics using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). Determine the affinity (KD) for both the therapeutic target and TfR1. Confirm that the affinity for the therapeutic target is higher than for TfR1 [30] [34].

- Step 3.2 – Functional Assay: Employ an in vitro BBB model, such as a transwell system with a monolayer of brain endothelial cells (e.g., hCMEC/D3). Apply the bispecific antibody to the apical compartment and measure the rate of transcytosis to the basolateral side, comparing it to a control monoclonal antibody [30].

Phase 4: In Vivo Validation

- Step 4.1 – Dosing: Administer the bispecific antibody intravenously to animal models (e.g., transgenic mice for Alzheimer's disease) at a therapeutically relevant dose (e.g., 1-10 mg/kg). Include a control group receiving a conventional monospecific antibody [31].

- Step 4.2 – Tissue Collection: At predetermined time points post-dosing, euthanize the animals and collect plasma, whole brain, and peripheral organs. Perfuse animals with saline to remove blood from the vasculature and ensure measured brain concentrations represent parenchymal delivery.

Phase 5: Bioanalytical and Functional Analysis

- Step 5.1 – Quantify Brain Exposure: Homogenize brain tissue and quantify antibody concentration using a specific ELISA that detects the bispecific format. Calculate the brain-to-plasma ratio to demonstrate enhanced penetration over conventional antibodies [30].

- Step 5.2 – Assess Target Engagement: For an anti-Aβ shuttle like trontinemab, use amyloid PET imaging or immunohistochemistry to quantify the reduction in plaque burden after repeated dosing. In clinical studies, a reduction below the 24 centiloid threshold is a key metric of efficacy [31] [32].

- Step 5.3 – Monitor Safety: Routinely conduct MRI scans to monitor for Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA), including ARIA-E (edema) and ARIA-H (microhemorrhages), which are known class effects of amyloid-lowering therapies [31] [36].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is monovalent binding to TfR1 preferred for bispecific antibody shuttles? Monovalent binding prevents the antibody from cross-linking TfR1 receptors on the endothelial cell surface. Bivalent binding, with its higher avidity, often leads to the shuttle being trafficked to the lysosome for degradation rather than being transcytosed across the cell. Monovalent, medium-affinity binding optimizes the shuttle for release and delivery into the brain parenchyma [30].

Q2: What are the critical quality attributes (CQAs) to monitor during bispecific shuttle production? Beyond standard antibody CQAs, you must closely monitor:

- Correct Chain Association: Use assays to confirm the proper heterodimer formation and absence of homodimers.

- Binding Activity for Both Targets: Ensure both antigen-binding sites are functional and have the correct affinity.

- Aggregation and Fragmentation: These molecules can be prone to instability, so use size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and capillary electrophoresis to monitor for aggregates and fragments [33] [34].

- Charge Variants: Analyze by imaged capillary isoelectric focusing (icIEF) to ensure product consistency.

Q3: Our shuttle shows excellent brain uptake in mice but fails in a higher species. What could be wrong? A common issue is a lack of cross-reactivity of the TfR1-binding domain. The shuttle's binding domain must be engineered to recognize TfR1 from the species used in your preclinical models and human TfR1. Always verify binding affinity and transcytosis efficiency in in vitro models expressing the human receptor before moving into clinical development [30].

Q4: How is clinical efficacy validated for a bispecific antibody shuttle in Alzheimer's disease? In clinical trials, efficacy is multi-faceted. For anti-amyloid shuttles like trontinemab, key endpoints include:

- Biomarker Efficacy: Rapid and significant reduction of amyloid plaques measured by amyloid PET (e.g., achieving amyloid-negative status) [31] [32].

- Clinical Efficacy: Slowing of cognitive and functional decline, measured by scales like the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), compared to placebo over 18 months [31] [36].

- Pharmacodynamic Effects: Reduction of downstream biomarkers like CSF/plasma pTau181 and pTau217 [31] [32].

Q5: What formulation strategies can improve the stability of bispecific antibody shuttles? BsAbs are often less stable than traditional mAbs. A proactive formulation strategy is essential:

- Early Developability Assessment: Screen for stability liabilities during candidate selection.

- Excipient Screening: Use high-throughput screening to identify optimal buffer conditions, pH, and stabilizers (e.g., sugars, surfactants, amino acids) that minimize aggregation and viscosity.

- Forced Degradation Studies: Subject the drug substance to stress conditions (e.g., thermal, mechanical) to identify degradation pathways and refine the formulation [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bispecific Shuttle Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Development | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|