Overcoming the Endolysosomal Barrier: Strategies for Nanoparticle Stability in Acidic pH Environments

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals tackling nanoparticle instability in endolysosomal compartments.

Overcoming the Endolysosomal Barrier: Strategies for Nanoparticle Stability in Acidic pH Environments

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals tackling nanoparticle instability in endolysosomal compartments. We first explore the fundamental mechanisms of degradation driven by acidic pH and hydrolytic enzymes. We then detail current methodologies for engineering stable nanoparticles, including material selection and surface functionalization. The guide addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization techniques for enhanced performance. Finally, we present validation frameworks and comparative analyses of leading strategies, concluding with future directions for translating stable nanocarriers into effective clinical therapies.

Understanding the Challenge: The Mechanisms of Endolysosomal Degradation

Technical Support Center

Welcome to the Endolysosomal Drug Delivery Troubleshooting Center. This guide addresses common experimental challenges in nanoparticle-based drug delivery research, framed within the thesis of improving nanoparticle stability in acidic endolysosomal environments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My nanoparticles show excellent encapsulation efficiency but consistently fail to release their cargo in the target cell cytosol. What could be going wrong? A: This is a classic sign of endolysosomal entrapment. The nanoparticles are likely being efficiently internalized but are then trapped and potentially degraded within the acidic lysosomal compartment. To troubleshoot:

- Verify Uptake Mechanism: Use pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., chlorpromazine for clathrin-mediated endocytosis, amiloride for macropinocytosis) to confirm the primary uptake pathway. Non-specific or undesired pathways may lead directly to degradative compartments.

- Assess Endosomal Escape: Perform a co-localization assay. Stain lysosomes (LAMP1 antibody or Lysotracker) and your nanoparticles (with a fluorescent tag). High Pearson's coefficient (>0.7) after 2-4 hours confirms lysosomal trapping.

- Solution: Redesign nanoparticles to include endosomolytic agents (e.g., peptides like GALA, polymers like PEI, or pH-sensitive lipids) that disrupt the endosomal membrane at low pH.

Q2: How can I accurately measure and track the pH environment my nanoparticles experience after cellular uptake? A: Use ratiometric pH-sensitive fluorescent probes.

- Protocol: Co-encapsulate a pH-sensitive dye (e.g., SNARF-1, FAM) and a pH-insensitive reference dye (e.g., Cy5) within your nanoparticles. After cellular incubation, perform live-cell imaging or flow cytometry.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the ratio of fluorescence intensity (pH-sensitive/pH-insensitive). Compare this ratio to a standard curve generated by measuring the same nanoparticles in buffers of known pH (4.0-7.4).

- Key Reagent: LysoSensor Yellow/Blue DND-160 can be used to stain acidic organelles independently to confirm the nanoparticle's location relative to the pH gradient.

Q3: My "pH-sensitive" nanoparticles are aggregating prematurely in cell culture media at neutral pH. How can I improve their serum stability? A: Premature aggregation often indicates insufficient colloidal stability or interaction with serum proteins (opsonization).

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Hydrodynamic Size & PDI: Use DLS to measure nanoparticle size in water vs. complete cell culture media over 24 hours. An increase >20 nm or PDI >0.2 indicates instability.

- Surface Modification: Introduce steric stabilizers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) ("PEGylation") or use biocompatible polymers (e.g., poloxamers). Consider engineering the surface charge to be slightly negative to reduce non-specific interactions.

- Test in Increments: Incubate nanoparticles in increasing concentrations of serum (10%, 50%, 100%) for 1 hour before DLS measurement to identify the stability threshold.

Q4: What are the best controls to prove my nanoparticle's functionality is specifically due to pH-triggered mechanisms in the endolysosome? A: Employ a combination of biological and material controls.

- Biological Control: Treat cells with Bafilomycin A1 (a vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitor). This drug raises endolysosomal pH. If your nanoparticle's efficacy (e.g., drug release, endosomal escape) is diminished upon Bafilomycin A1 treatment, it confirms pH-dependent functionality.

- Material Control: Synthesize a non-responsive nanoparticle variant identical in every way except the pH-sensitive component (e.g., use a non-cleavable linker instead of a pH-labile one). Compare performance directly.

Experimental Protocol Library

Protocol 1: Quantitative Analysis of Endolysosomal Colocalization Objective: To determine the percentage of internalized nanoparticles that co-localize with lysosomes over time. Materials: Fluorescently labeled nanoparticles, Lysotracker Deep Red, Hoechst 33342, live-cell imaging medium, confocal microscope. Steps:

- Seed cells in an 8-well chambered cover glass.

- Incubate with nanoparticles (e.g., 50 µg/mL) for a defined pulse period (e.g., 2h).

- Replace medium with fresh, nanoparticle-free medium. This starts the "chase" period.

- At chase time points (0, 2, 4, 8h), stain cells with Lysotracker (50 nM, 30 min) and Hoechst (5 µg/mL, 10 min).

- Acquire z-stack images using appropriate laser lines. Maintain identical acquisition settings across all samples.

- Analysis: Use ImageJ/Fiji with coloc2 plugin or similar software. Apply threshold to each channel. Calculate Manders' overlap coefficients (M1 = fraction of nanoparticle signal overlapping lysosomes; M2 = fraction of lysosome signal overlapping nanoparticles). Report M1 over time.

Protocol 2: In Vitro pH-Triggered Drug Release Kinetics Objective: To characterize the release profile of encapsulated cargo under simulated endolysosomal pH conditions. Materials: Nanoparticles with encapsulated model drug (e.g., doxorubicin or FITC-dextran), dialysis tubes (MWCO appropriate for cargo), release buffers (PBS at pH 7.4, 6.5, 5.0, and 4.5), fluorometer/spectrophotometer. Steps:

- Place nanoparticle suspension (1 mL) into a dialysis bag.

- Immerse the bag in 50 mL of release buffer (sink condition) with gentle stirring at 37°C.

- At predetermined time intervals, withdraw 1 mL of the external buffer and replace with fresh pre-warmed buffer.

- Quantify the amount of released cargo in the withdrawn samples using a pre-established calibration curve (e.g., fluorescence/absorbance).

- Calculate cumulative release percentage. Plot release (%) vs. time for each pH.

Table 1: Common Endolysosomal Disruption Agents and Their Mechanisms

| Agent Class | Example | Mechanism of Action | Typical Working Concentration | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proton Sponge Polymer | Polyethylenimine (PEI, 25kDa) | Buffers acidic pH, causes osmotic swelling and rupture. | 0.5-2 µg/mL for transfection | High cytotoxicity at effective doses. |

| pH-Sensitive Peptide | GALA (30 aa) | Forms α-helix at low pH, inserts into and disrupts lipid bilayers. | 10-50 µM | Can be sensitive to serum proteases. |

| Lipid | DOPE (helper lipid) | Promotes transition to hexagonal (HII) phase at low pH, fusing with endosomal membrane. | 20-50 mol% in formulation | Requires combination with stable lipid (e.g., DSPC). |

| Pore-Forming Protein | Listeriolysin O (LLO) | Forms large pores in cholesterol-containing membranes at acidic pH. | 0.1-1 µg/mL | Immunogenic; used primarily in research. |

Table 2: Standard Endolysosomal pH and Marker Proteins

| Compartment | Approximate pH Range | Key Marker Protein(s) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Endosome | 6.0 - 6.5 | EEA1, Rab5 | Sorting of cargo for recycling or degradation. |

| Late Endosome | 5.0 - 6.0 | Rab7, CD63 | Transport to lysosomes; further acidification. |

| Lysosome | 4.5 - 5.0 | LAMP1/2, Cathepsin D | Terminal degradation of biomolecules. |

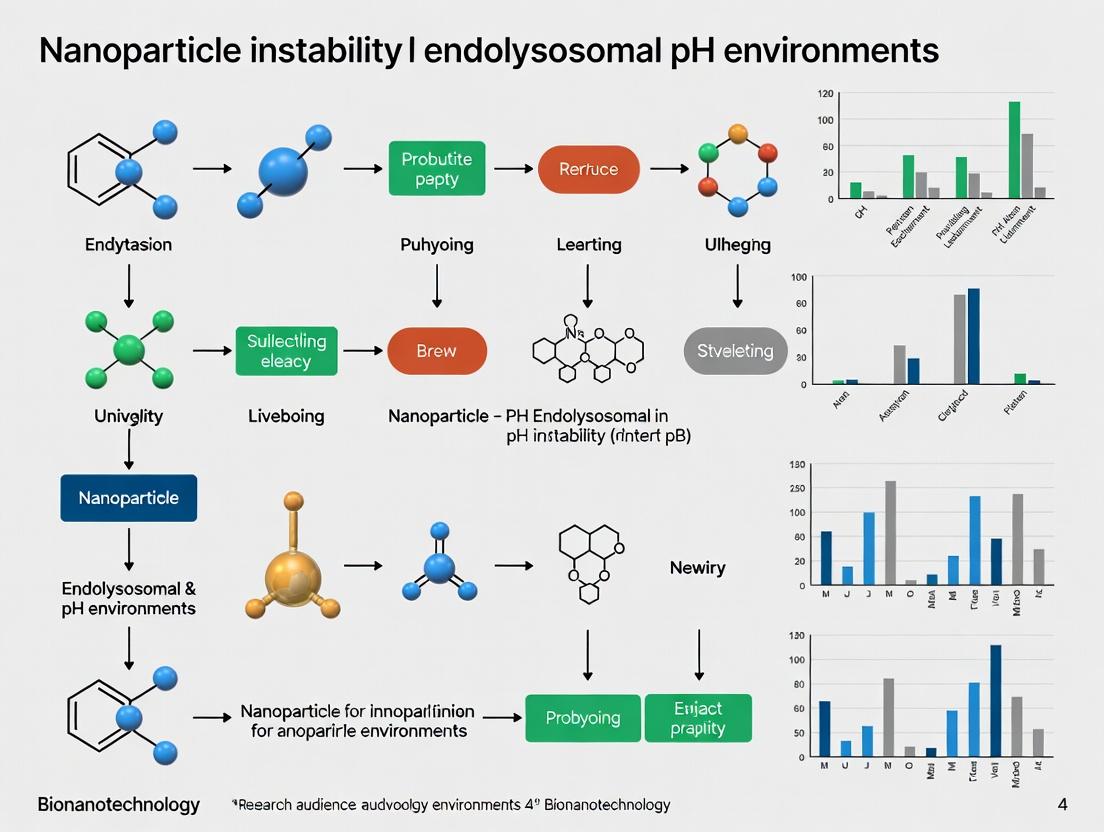

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Nanoparticle Endolysosomal Trafficking & Escape Routes

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for pH-Stability Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lysotracker Probes (e.g., Deep Red, Green DND-26) | Fluorescent dyes that accumulate in acidic organelles for live-cell imaging of endolysosomal compartments. | Choose a fluorophore distinct from nanoparticle label. Concentration and time must be optimized to avoid toxicity. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Specific inhibitor of V-ATPase, used to neutralize endolysosomal pH and test pH-dependence of nanoparticle function. | Highly toxic; use low doses (e.g., 50-100 nM) and short incubation times (1-2h pretreatment). |

| Chloroquine | Lysosomotropic agent that raises lysosomal pH and can itself promote "proton sponge" like escape. Often used as a control or enhancer. | Mechanism is broad; can confound results of specific pH-triggered mechanisms. |

| DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) | A pH-sensitive helper lipid used in liposomal/LNP formulations to promote endosomal membrane fusion/disruption. | Requires combination with a stable lipid (e.g., cholesterol, DSPC) for structural integrity pre-trigger. |

| Ratiometric pH Dyes (e.g., SNARF-1, pHrodo) | Encapsulated or conjugated to nanoparticles to directly measure the pH of their microenvironment via fluorescence ratio imaging. | Requires careful calibration and controls for dye leakage. |

| Dynasore | Cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin, used to block clathrin-mediated endocytosis and study uptake pathways. | Can have off-target effects; use alongside other pathway inhibitors (e.g., nystatin, EIPA) for conclusive results. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My nanoparticles aggregate rapidly upon exposure to a pH 5.0 buffer, but are stable at pH 7.4. What is the primary cause and how can I troubleshoot this? A: Rapid aggregation at endolysosomal pH (4.5-5.5) is frequently caused by protonation of surface stabilizers (e.g., carboxylate groups), reducing electrostatic repulsion. Ionic strength of the lysosomal milieu (∼150 mM) can further screen surface charges.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Measure Zeta Potential: Quantify the surface charge shift from pH 7.4 to 5.0 using dynamic light scattering (DLS). A drop towards neutral zeta potential (< |±10| mV) confirms loss of electrostatic stability.

- Check for Protonatable Groups: Review your nanoparticle coating chemistry. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) with terminal carboxylic acid is common but protonates at low pH. Consider switching to sulfonate groups or PEG with terminal hydroxyl groups.

- Incorporate pH-Responsive Steric Stabilizers: Introduce stabilizers that gain steric bulk or become more hydrophilic at low pH, such as polymers containing tertiary amine groups that protonate and swell.

Q2: I suspect hydrolytic enzymes are degrading my lipid-based nanoparticle (LNP) cargo before it can escape the endolysosome. How can I confirm and mitigate this? A: Lysosomal hydrolases (e.g., lipases, proteases, nucleases) are highly active at acidic pH. Degradation can be confirmed and addressed methodically.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- In Vitro Degradation Assay: Incubate your nanoparticle/cargo with isolated lysosomal enzymes (commercially available) in pH 5.0 buffer. Use gel electrophoresis, HPLC, or fluorescence assays to monitor cargo integrity over time against a pH 7.4 control.

- Use Enzyme Inhibitors: Include broad-spectrum inhibitors like pepstatin A (aspartic proteases) and leupeptin (serine/cysteine proteases) in cell-based experiments. If cargo release/ efficacy improves, enzyme degradation is confirmed.

- Employ Endosomolytic Agents: Co-formulate or conjugate agents that promote endosomal escape. These include:

- Fusogenic Lipids: DOPE (dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine) promotes transition to hexagonal phase at low pH.

- Peptides: pH-responsive cell-penetrating peptides (e.g., GALA, INF7) undergo conformational change, disrupting the endosomal membrane.

Q3: My experimental readout shows poor endosomal escape efficiency. How can I determine if the culprit is low pH, enzymes, or ionic strength? A: Isolate variables using a structured experimental protocol.

- Experimental Protocol: Isolating the Key Culprits

- Prepare Three Simulated Lysosomal Media:

- Buffer A: 25 mM MES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.0 (Acidic pH + Ionic Strength).

- Buffer B: 25 mM MES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.0 + 0.1 mg/mL Lysosomal Enzyme Cocktail (Acidic pH + Ionic Strength + Enzymes).

- Buffer C: 25 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 (Control).

- Incubate nanoparticles loaded with a fluorescent reporter (e.g., calcein, siRNA-Cy5) in each buffer at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Analyze: Use DLS for size (aggregation), fluorescence spectroscopy/quenching for cargo retention (degradation/leakage), and agarose gel retardation for nucleic acid integrity.

- Interpretation: Compare A vs. C → pH/Ionic Strength effect. Compare B vs. A → Enzymatic effect.

- Prepare Three Simulated Lysosomal Media:

Table 1: Impact of Simulated Lysosomal Conditions on Model Nanoparticle Formulations

| Nanoparticle Type (Core/Coating) | Size Change (pH 7.4 vs 5.0) | Zeta Potential Shift (pH 7.4 vs 5.0) | Cargo Retention after 1h (pH 5.0 + Enzymes) | Key Instability Driver Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA-PEG-COOH | +220% (Aggregation) | -35 mV → -5 mV | 45% | Acidic pH (Charge neutralization) |

| Cationic Lipid/DNA Complex | +150% (Aggregation) | +40 mV → +15 mV | 15% | Ionic Strength (Charge screening) & Enzymes |

| Chitosan/siRNA Polyplex | +25% (Swelling) | +30 mV → +42 mV | 60% | Enzymatic Degradation (of chitosan) |

| DOPE/CHEMS pH-Sensitive Liposome | -15% (Shrinking) | -10 mV → -5 mV | 85% | Minimal (Designed for pH-response) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing pH-Dependent Aggregation via DLS and Zeta Potential Objective: Quantify nanoparticle instability due to acidic pH and ionic strength. Materials: Nanoparticle suspension, 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), 20 mM MES buffer (pH 5.0), 150 mM NaCl, DLS/Zeta Potential analyzer. Method:

- Dialyze nanoparticle suspension overnight against 20 mM HEPES + 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4.

- Prepare 1 mL of nanoparticle sample in the pH 7.4 buffer (1 mg/mL).

- Prepare 1 mL of nanoparticle sample in the MES + 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.0 buffer.

- Equilibrate both samples at 25°C for 10 minutes.

- Load into the instrument's cuvette. Measure the hydrodynamic diameter (by intensity) and polydispersity index (PDI) via DLS. Perform zeta potential measurement using electrophoretic light scattering.

- Compare the average size, PDI, and zeta potential between the two conditions. An increase in size/PDI and a reduction in zeta potential magnitude indicates pH/ionic strength-driven instability.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Enzymatic Degradation Assay for Polymeric Nanoparticles Objective: Evaluate the susceptibility of nanoparticles to lysosomal hydrolases. Materials: Fluorescently labeled nanoparticles, Simulated Lysosomal Fluid (SLF) pH 5.0 (commercial or prepared with enzymes), microcentrifuge tubes, fluorescence plate reader, dialysis membrane (optional). Method:

- Prepare SLF pH 5.0 according to supplier instructions, containing a mix of relevant hydrolases (e.g., phosphatases, lipases, proteases).

- In a microcentrifuge tube, mix 100 µL of nanoparticle suspension (1 mg/mL) with 400 µL of SLF pH 5.0. Prepare a control with nanoparticles in enzyme-free pH 5.0 buffer.

- Incubate at 37°C with gentle shaking.

- At time points (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 min), take 50 µL aliquots.

- Option A (Free Dye): Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 20,000 g) to pellet nanoparticles. Measure fluorescence of the supernatant (released dye/cargo) against a standard curve.

- Option B (FRET): If nanoparticles are loaded with a FRET pair, measure the change in FRET signal directly from the aliquot.

- Plot % cargo retained vs. time. A faster decay in the SLF sample vs. control confirms enzymatic degradation.

Diagrams

Title: Nanoparticle Instability Pathway in Endolysosomal System

Title: Troubleshooting Flowchart for Endolysosomal Instability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Studying Endolysosomal Nanoparticle Instability

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| MES (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid) Buffer | A buffering agent effective in the pH range of 5.5-6.7, used to accurately simulate early/late endosomal pH conditions. |

| Citrate-Phosphate Buffer | Provides stable buffering capacity in the lysosomal pH range (4.0-5.5) for in vitro degradation studies. |

| Lysosomal Enzyme Cocktail (from mouse liver or human cell lines) | A mixture of purified hydrolases used in simulated lysosomal fluid (SLF) to test enzymatic degradation of nanoparticles in vitro. |

| Pepstatin A & E-64d | Cell-permeable inhibitors of aspartic proteases and cysteine proteases, respectively. Used in cell assays to confirm protease-driven cargo loss. |

| Chloroquine | A lysosomotropic agent that raises endolysosomal pH. Serves as a positive control to test if low pH is the primary instability trigger. |

| DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) | A pH-sensitive, fusogenic phospholipid used in liposomal formulations to promote endosomal membrane disruption and escape. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | A specific inhibitor of the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) that prevents endosomal acidification. Critical for confirming pH-sensitive mechanisms. |

| Calcein (self-quenching concentration) | A fluorescent dye used as a marker for endosomal escape. Release into cytosol causes de-quenching and a detectable fluorescent signal increase. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: How can I differentiate between nanoparticle dissolution and aggregation in my TEM images? A: Dissolution appears as a loss of structural integrity, blurred or missing particle boundaries, and a decrease in electron density. Aggregation is seen as clusters of individual particles maintaining their distinct cores but in close physical contact. Use energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) on the suspect area; a significant drop in core material signal indicates dissolution.

Q2: My nanoparticle formulation shows rapid payload release at pH 7.4, but is stable at pH 5.0. What could be wrong? A: This inverted stability profile suggests a formulation or materials error. The most common cause is incorrect polymer block ratio for pH-sensitive designs (e.g., PEG-PLA/DSPE). Verify the chemical structure and molecular weight of your pH-sensitive polymer (e.g., poly(histidine), acylhydrazone linkers). Perform a control experiment using a non-pH-sensitive but otherwise identical nanoparticle.

Q3: I observe massive aggregation only after endolysosomal exposure in cell studies, not in buffer. Why? A: This points to biomolecular corona-driven aggregation. Proteins and other biomolecules adsorb to the nanoparticle surface in the biological milieu, altering zeta potential and steric stability. Characterize the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential after incubation in full cell culture media (with serum) for 1 hour, not just in PBS or water.

Q4: How do I experimentally prove payload premature release is happening inside the endolysosome and not elsewhere? A: Employ a Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based payload pair. Co-encapsulate donor and acceptor dyes. Intact nanoparticles show FRET signal; payload release quenches it. Use live-cell imaging with lysosomal trackers (e.g., LysoTracker) and a FRET channel. Co-localization of lysosome signal with loss of FRET signal confirms endolysosomal release.

Q5: What are the key controls to include when studying dissolution in acidic pH? A:

- Material Control: Incubate the raw core material (e.g., free drug, iron oxide crystals) under identical conditions.

- Surface Coating Control: Test nanoparticles with inert, non-degradable coatings (e.g., silica shell).

- Chelator Control: For metal-based nanoparticles, include a condition with a chelating agent (e.g., EDTA) to confirm ion-mediated dissolution.

- Time-Zero Control: Characterize (size, concentration) immediately before initiating the experiment.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Dissolution Kinetics of Metallic Nanoparticles

- Objective: Measure the rate of ion release from nanoparticles in an endolysosomal-mimetic buffer.

- Materials: Nanoparticle suspension, Sodium Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5-5.0), Dialysis bag (MWCO 3.5 kDa), Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS).

- Procedure:

- Dialyze a known concentration of nanoparticles against 500x volume of Sodium Acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Collect aliquots of the external buffer at defined time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 h).

- Analyze the ion concentration (e.g., Fe, Au, Si) in each aliquot via ICP-MS.

- Calculate the cumulative percentage of dissolved material over time.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Aggregation Dynamics via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

- Objective: Assess nanoparticle size stability under a pH gradient.

- Materials: Nanoparticle suspension, PBS (pH 7.4), Acetate buffer (pH 5.0), DLS instrument with temperature control.

- Procedure:

- Dilute nanoparticles into pre-warmed (37°C) PBS (pH 7.4) and immediately measure hydrodynamic diameter (Z-avg) and polydispersity index (PDI). Record 3 measurements.

- Rapidly acidify the same cuvette by adding a calculated small volume of 1.0 M HCl or acidic buffer to achieve pH 5.0. Mix gently.

- Continuously monitor Z-avg and PDI every minute for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- A sustained increase in Z-avg and PDI indicates aggregation. A transient peak may indicate reversible clustering.

Protocol 3: Assessing Payload Release with Dialysis

- Objective: Quantify premature payload release under simulated physiological conditions.

- Materials: Payload-loaded nanoparticles, Release media (PBS pH 7.4, Acetate buffer pH 5.0, both with 0.5% w/v Tween 80 to maintain sink conditions), Franz diffusion cell or dialysis setup, HPLC.

- Procedure:

- Place nanoparticle suspension in the donor chamber/dialysis bag.

- Fill receptor chamber with pre-warmed (37°C) release media.

- At predetermined intervals, withdraw a known volume from the receptor chamber and replace with fresh media.

- Analyze the withdrawn samples via HPLC to quantify released payload.

- Plot cumulative release (%) versus time for each pH condition.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Degradation Kinetics of Common Nanoparticle Cores at pH 5.0

| Nanoparticle Core | Coating | 24h Dissolution (%) (ICP-MS) | 1h Size Increase (%) at pH 5.0 (DLS) | Critical Aggregation pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous Silica | PEG | 8.2 ± 1.5 | 15 ± 3 | <4.5 |

| Iron Oxide (Fe3O4) | Citrate | 45.3 ± 5.1 | 250 ± 45 | ~5.5 |

| Calcium Phosphate | PEG-lipid | 92.0 ± 8.7 | N/A (complete dissolution) | N/A |

| PLGA Polymer | Poloxamer 188 | N/A | 5 ± 1 (swelling) | N/A |

| Gold Nanosphere | PEG-Thiol | <0.1 ± 0.05 | 2 ± 1 | N/A |

Table 2: Payload Release Profiles from pH-Sensitive Nanocarriers

| Nanocarrier Type | Payload | % Release at 24h (pH 7.4) | % Release at 24h (pH 5.0) | Trigger Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposome (DOPE/CHEMS) | Doxorubicin | 12 ± 2 | 85 ± 4 | Membrane fusion |

| PEG-PLA micelle | Docetaxel | 18 ± 3 | 22 ± 3 | Hydrolysis |

| Poly(β-amino ester) | siRNA | 5 ± 1 | 95 ± 3 | Polymer swelling/burst |

| Acetal-linked PEG | Model Protein | 8 ± 2 | 68 ± 6 | Linker hydrolysis |

Visualizations

Title: Nanoparticle Dissolution Pathway in Low pH

Title: Instability Mechanism Diagnostic Flowchart

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Stability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Sodium Acetate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5-5.0) | Mimics the endolysosomal pH environment for in vitro stability testing. |

| LysoTracker Deep Red | Fluorescent dye for live-cell imaging of lysosomes. Confirms nanoparticle co-localization. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor. Used as a control to alkalinize endolysosomes and inhibit pH-driven processes. |

| PEGylated Phospholipids (e.g., DSPE-mPEG) | Provides steric stabilization. Added to formulations to mitigate aggregation via biomolecular corona. |

| FRET Pair (e.g., DiO/DiI) | Donor/acceptor lipophilic dyes. Co-encapsulation allows visualization of carrier integrity and payload release. |

| ICP-MS Standard Solutions | Critical for quantifying metal ion concentrations with high sensitivity to calculate dissolution rates. |

| Sucrose (for Sucrose Lysis Protocol) | Used to isolate endolysosomal compartments from cells for direct analysis of nanoparticle state. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Purifies nanoparticles from unencapsulated payload or aggregates before and after stability tests. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting for Nanoparticle Endolysosomal Stability Research

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers working on nanoparticle drug delivery systems, specifically within the context of a thesis focused on addressing instability in endolysosomal pH environments. Below are troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and essential resources for your experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My nanoparticle cargo is degrading prematurely in in vitro cell assays, leading to low therapeutic efficacy. What could be the cause? A: This is a classic symptom of nanoparticle instability in the endolysosomal pathway (pH 4.5-5.0). The acidic pH and enzymatic environment can degrade the nanoparticle structure, causing early cargo release. First, verify the pH-buffering capacity of your nanoparticle formulation using an acid titration assay. Consider incorporating pH-responsive or "proton-sponge" materials (e.g., polyethyleneimine) that can promote endosomal escape.

Q2: I am observing significant cytotoxicity in non-target cell lines during my experiments. How can I determine if this is an off-target effect from instability? A: Off-target cytotoxicity often results from uncontrolled payload release in the bloodstream (pH 7.4) or in non-target tissues due to particle disintegration. Perform a serum stability assay: incubate nanoparticles in 50-100% serum at 37°C and measure size (via DLS) and polydispersity index (PDI) over 24 hours. An increase in PDI >0.2 or a significant size shift indicates instability leading to off-target effects. See Table 1 for quantitative benchmarks.

Q3: My fluorescently labeled nanoparticles show a diffuse signal in the cytoplasm instead of a localized therapeutic effect. What does this indicate? A: A diffuse cytoplasmic signal suggests lysosomal rupture and uncontrolled release, which can lead to off-target activity and reduced efficacy. This is often due to excessive polymer swelling or membrane disruption in the endolysosome. Optimize the density of ionizable groups on your carrier. Implement a co-localization assay using LysoTracker dyes to quantify the percentage of nanoparticles that successfully escape versus those trapped in lysosomes.

Q4: How can I quantitatively measure endolysosomal escape efficiency? A: A standard protocol involves using a Galectin-8 (or Galectin-9) recruitment assay. Galectin-8 binds to exposed glycans on damaged endosomal membranes. Transfect cells with a fluorescent Galectin-8 reporter, treat with nanoparticles, and quantify the co-localization puncta via high-content imaging. Higher counts indicate greater membrane disruption, which can be correlated with escape efficiency and potential instability.

Table 1: Serum Stability Benchmarks and Associated Risks

| Time Point (hr) | Stable Nanoparticle PDI | Unstable Nanoparticle PDI | Observed Risk Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.08 - 0.12 | 0.10 - 0.15 | Baseline |

| 4 | < 0.15 | > 0.25 | Early off-target release begins |

| 12 | < 0.18 | > 0.35 | Significant efficacy loss (>30%) |

| 24 | < 0.20 | > 0.40 | High cytotoxicity in non-target cells |

Table 2: Correlation Between Endolysosomal pH Buffering Capacity and Therapeutic Outcomes

| ΔpH (Buffering Capacity)* | Escape Efficiency (%) | Measured Efficacy (IC50 Improvement) | Reported Off-Target Cytotoxicity (LD50) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (< 0.5 pH units) | 10-25% | < 2-fold | Low (>100 µM) |

| Moderate (0.5-1.0) | 25-60% | 2- to 5-fold | Moderate (50-100 µM) |

| High (> 1.0) | 60-90% | 5- to 10-fold | High (< 50 µM) |

*ΔpH: Change in pH upon addition of a standardized acid aliquot to nanoparticle solution.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Acid Titration Assay for Buffering Capacity

- Prepare: Dialyze nanoparticle suspension (5 mg/mL) against 150 mM NaCl.

- Setup: Place 10 mL of nanoparticle suspension under magnetic stirring at 25°C with a calibrated pH electrode.

- Titrate: Using a micro-syringe pump, add 0.1 M HCl at a constant rate (e.g., 0.5 mL/hr).

- Record: Continuously log pH vs. volume of acid added.

- Analyze: Plot the data. The plateau region indicates the buffering capacity. Calculate the ΔpH between physiological (7.4) and lysosomal pH (4.5).

Protocol 2: Galectin-8 Recruitment Assay for Endolysosomal Damage

- Seed Cells: Plate HeLa or relevant cell line in an imaging plate.

- Transfert: Transfect cells with a plasmid encoding fluorescent protein-tagged Galectin-8 (e.g., GFP-Galectin-8) 24 hours prior.

- Treat: Add nanoparticles at desired concentration for 2-4 hours.

- Fix & Image: Fix cells with 4% PFA, stain nuclei with DAPI, and image using a confocal microscope.

- Quantify: Use ImageJ to count the number of distinct GFP-Galectin-8 puncta per cell. Compare to untreated controls.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Stability Research |

|---|---|

| LysoTracker Deep Red | Fluorescent dye for labeling and tracking acidic organelles (lysosomes) in live cells. |

| Chloroquine | Positive control for endolysosomal escape; a lysosomotropic agent that neutralizes pH. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Inhibitor of vacuolar H+-ATPase; used to block acidification and confirm pH-dependent mechanisms. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI, 25kDa) | Cationic "proton-sponge" polymer reference standard for pH-buffering capacity assays. |

| DLS / Zetasizer Instrument | For measuring hydrodynamic diameter and PDI to assess aggregation and stability in serum. |

| FRET-based Nanoparticle Probes | Particles with donor/acceptor dyes; FRET loss quantifies disassembly/cargo release kinetics. |

Diagrams

Title: Nanoparticle Fate After Cellular Uptake

Title: Logic of Instability Consequences

Title: Serum Stability Assay Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: My in vitro lysosomal simulant buffer is precipitating. What is the cause and solution?

- Answer: Precipitation is commonly due to the phosphate component reacting with calcium or magnesium ions in the nanoparticle formulation or from other buffers. Use an organic buffer like MES or acetate for the acidic pH range. Alternatively, prepare a phosphate-free simulant using sodium citrate/citric acid (pH 4.5-5.0) or ammonium acetate/acetic acid (pH 4.0).

FAQ 2: I observe high variability in my cell-based lysosomal escape assay. How can I improve reproducibility?

- Answer: High variability often stems from inconsistent cell health, lysosomal pH, or nanoparticle dosing.

- Cell Health: Ensure consistent passage number and confluency. Use cells within passages 5-20.

- Lysosomal pH: Pre-treat cells with Bafilomycin A1 (100 nM, 1 hour) as a control to inhibit v-ATPase and neutralize lysosomal pH. If your signal changes, the assay is pH-sensitive.

- Dosing: Use a synchronized uptake protocol: pre-chill cells to 4°C, add nanoparticles, incubate at 4°C for 30 min to allow binding but not internalization, then wash and shift to 37°C to initiate synchronized endocytosis.

FAQ 3: How do I differentiate between true lysosomal escape and nanoparticle degradation/release of cargo in simulant assays?

- Answer: You need a multi-modal readout.

- For Fluorescently-Labeled Nanoparticles: Use a Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) pair. Intact nanoparticles show FRET; degradation or dissociation quenches FRET. A increase in donor emission indicates disassembly.

- For Cargo Release: Use a fluorophore-quencher pair on the cargo molecule itself (e.g., a labeled siRNA). Dequenching upon release from the nanoparticle indicates cargo liberation. Correlate this with dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements of the nanoparticle hydrodynamic size in the simulant over time to confirm disintegration.

FAQ 4: My control nanoparticles (stable at lysosomal pH) are still showing signal in the lysosomal escape assay. What's wrong?

- Answer: This indicates potential false positives from lysosomal leakage or photobleaching artifacts.

- Control: Include a positive control for lysosomal membrane integrity, such as co-staining with Galectin-3 (mCherry-Gal3), which punctately recruits upon membrane damage.

- Imaging Artifacts: Perform a "quench" control. Use a membrane-impermeable fluorescence quencher (e.g., Trypan Blue for fluorescein dyes) added extracellularly after fixation. It will only quench fluorescence from nanoparticles that have escaped into the cytosol, not those inside intact lysosomes.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of a Standardized In Vitro Lysosomal Simulant Buffer

Purpose: To create a biorelevant medium mimicking the late endosome/lysosome environment for nanoparticle stability testing. Reagents: Sodium citrate, Citric acid, Sodium chloride, Magnesium sulfate, Calcium chloride, Sodium acetate, Acetic acid. Method:

- Prepare a 10x stock solution: 200 mM Sodium Citrate, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgSO₄, 5 mM CaCl₂. Adjust to pH 5.0 using citric acid. Filter sterilize (0.22 µm).

- For a 1x working solution (10 mL), dilute 1 mL of 10x stock into 9 mL of sterile water.

- Validate pH using a calibrated micro pH electrode. Store at 4°C for up to 2 weeks.

Protocol 2: Flow Cytometry-Based Lysosomal Escape Assay

Purpose: To quantitatively assess the ability of nanoparticles to deliver a fluorescent cargo to the cytoplasm. Reagents: Cells (e.g., HeLa), nanoparticles with fluorescent cargo (e.g., Cy5-siRNA), Bafilomycin A1, Hoechst 33342, Trypan Blue. Method:

- Seed cells in a 24-well plate at 70% confluency and incubate for 24h.

- Optional Control: Pre-treat one set of wells with 100 nM Bafilomycin A1 for 1h.

- Treat cells with nanoparticles (e.g., 50 nM siRNA equivalent) for 4-6h in serum-free media.

- Replace media with complete growth media and incubate further for 18-48h (depending on cargo mechanism).

- Harvest cells with trypsin, wash with PBS, and resuspend in PBS containing 1 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 (live-cell stain).

- Quench Step (Critical): Add Trypan Blue to a final concentration of 0.4% (w/v) to the cell suspension 5 minutes before analysis to quench extracellular and lysosomal fluorescence.

- Analyze immediately by flow cytometry. Measure fluorescence in the Cy5 channel (or relevant channel). The population shift in median fluorescence intensity (MFI) with and without quench indicates cytosolic delivery.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Composition of Common In Vitro Lysosomal Simulants

| Component | Standard Phosphate Buffer (pH 5.0) | Citrate-Based Simulant (pH 5.0) | Acetate-Based Simulant (pH 4.5) | Artificial Lysosomal Fluid (ALF, pH 4.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Buffer | NaH₂PO₄ (20 mM) | Sodium Citrate (20 mM) | Sodium Acetate (25 mM) | Sodium Citrate (10 mM) |

| Acidifier | HCl | Citric Acid | Acetic Acid | Citric Acid |

| Osmolality Agent | NaCl (140 mM) | NaCl (140 mM) | NaCl (150 mM) | NaCl (150 mM) |

| Divalent Cations | None | MgSO₄ (1 mM), CaCl₂ (1 mM) | Optional | MgCl₂ (0.5 mM), CaCl₂ (0.5 mM) |

| Key Advantage | Simple | Biorelevant ions, less precipitation | Low cost, good for pH 4-5 | Standardized for biopersistence tests (ISO) |

| Main Disadvantage | Prone to precipitation with Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺ | Complexation with some metals | Less biological ion mimicry | Lower buffer capacity |

Table 2: Common Cell-Based Assays for Lysosomal Tracking and Escape

| Assay Name | Readout | What it Measures | Typical Tools/Reporters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-localization Analysis | Fluorescence Microscopy (Manders'/Pearson's Coefficient) | Nanoparticle entrapment in lysosomes | Lysotracker, LAMP1-GFP, Dextran markers |

| Fluorescence Quenching | Flow Cytometry or Microscopy (MFI change) | Cytosolic vs. vesicular localization | Trypan Blue, Anti-fluorophore antibodies |

| Galectin-3 Recruitment | Microscopy (Puncta formation) | Lysosomal membrane damage | mCherry-Gal3, GFP-Gal3 |

| Functional Cargo Delivery | Bioluminescence/Luciferase activity | Functional biological activity (e.g., gene silencing) | siRNA against firefly luciferase, Luc reporter cells |

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Nanoparticle Endolysosomal Trafficking Pathways

Diagram Title: Lysosomal Escape Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Lysosomal/ Nanoparticle Research |

|---|---|

| Bafilomycin A1 | Specific v-ATPase inhibitor. Used to neutralize lysosomal pH as a critical control to confirm pH-dependent processes. |

| Chloroquine | Lysosomotropic agent that buffers lysosomal pH, often used as a positive control for enhancing lysosomal escape. |

| Lysotracker Dyes | Cell-permeable, fluorescent weak bases that accumulate in acidic organelles (like lysosomes) for live-cell imaging. |

| Anti-LAMP1 Antibody | Gold-standard marker for immunofluorescence staining of lysosomal membranes. |

| Galectin-3 (mCherry/GFP) | Reporter protein that forms puncta upon binding to exposed glycans on damaged endolysosomal membranes, indicating escape. |

| Dextran, Texas Red- | Fluid-phase endocytosis marker. Co-incubation with NPs tracks general endolysosomal pathway progression. |

| Trypan Blue | Membrane-impermeable fluorescence quencher. Used post-fixation to distinguish cytosolic (unquenched) from vesicular (quenched) signal. |

| Ammonium Chloride (NH₄Cl) | Lysosomotropic agent used to rapidly raise lysosomal pH via osmotic swelling and buffer capacity. |

| Citrate-Based Buffer Salts | For preparing in vitro lysosomal simulants that avoid phosphate precipitation and include biorelevant ions. |

| FRET-pair labeled NPs | Nanoparticles engineered with donor/acceptor fluorophores. FRET loss directly indicates nanoparticle disassembly in real-time. |

Engineering for Stability: Core Designs and Surface Functionalization Strategies

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My polymeric nanoparticle (e.g., PBAE or poly(beta-amino ester)) formulation is aggregating during synthesis at pH 6.5. What is the cause? A: This is often due to premature protonation of the polymer's amine groups, reducing colloidal stability. Ensure the synthesis buffer is well below the polymer's pKa (typically 6-7 for endosomolytic polymers). Use a lower pH buffer (e.g., pH 5.0-5.5) during the nanoprecipitation process. If aggregation persists, increase the concentration of a stabilizing agent like poly(ethylene glycol)-block-polymer (PEG-b-PLGA) or poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) by 0.5-1% w/v.

Q2: The encapsulation efficiency (EE%) of my siRNA in pH-sensitive lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) is consistently below 70%. How can I improve it? A: Low EE% often stems from an incorrect N/P ratio (amine to phosphate ratio from cationic lipids to nucleic acid) or insufficient mixing during microfluidics formation. First, verify your N/P ratio. For ionizable lipids like DLin-MC3-DMA, the optimal N/P is typically between 3 and 6. Systematically test ratios in this range. Second, ensure the total flow rate (TFR) and flow rate ratio (FRR) in your microfluidic mixer are optimized. A TFR of 12 mL/min and an FRR (aqueous:organic) of 3:1 is a standard starting point. Increasing the TFR can improve mixing and EE%.

Q3: My inorganic silica-core nanoparticles are dissolving too quickly in the late endosome/lysosome mimic buffer (pH 4.5-5.0). How can I tune the degradation rate? A: The dissolution rate of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) is governed by silica condensation density. To slow degradation, post-synthesize a calcination step: heat particles to 450°C for 2 hours in air. Alternatively, incorporate a zirconia (ZrO₂) co-condensation during synthesis. A Si/Zr molar ratio of 10:1 can increase stability by ~40% at pH 4.5 while maintaining cargo release functionality.

Q4: The fusogenic lipid (e.g., DOPE) in my liposome formulation is causing instability during storage. What are my options? A: DOPE prefers a non-lamellar (hexagonal II) phase, which can lead to fusion and leakage over time. Stabilize the formulation by: 1) Increasing the molar percentage of a stabilizer like cholesterol from 30% to 40-45%. 2) Replacing a portion of DOPE with its methylated derivative, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (PEG-DOPE), at 5-10 mol%. This introduces steric stabilization. 3) Store lyophilized with 5% w/v trehalose as a cryoprotectant.

Q5: During in vitro testing, my "pH-resistant" nanoparticles are still showing significant cargo release in the cytoplasm mimic buffer (pH 7.4). What might be the issue? A: This indicates insufficient buffering capacity or premature destabilization. First, characterize the buffering capacity (β-value) of your polymer or lipid via acid-base titration. A β-value of 2-4 in the pH 4.5-7.4 range is optimal. A lower value suggests weak pH-dependency. Second, check for residual organic solvent (e.g., DCM, acetone) from synthesis via HPLC, as this can create pores. Implement a more rigorous dialysis (e.g., 48 hours with 3-4 buffer changes).

Table 1: pH-Dependent Degradation Rates of Common Inorganic Cores

| Material | Synthesis Method | Degradation Half-life (pH 7.4) | Degradation Half-life (pH 5.0) | Key Stabilizing Dopant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous Silica (MSN) | Sol-gel (CTAB template) | >14 days | 12-48 hours | ZrO₂, Al₂O₃ |

| Calcium Phosphate | Co-precipitation | 10 days | 4-6 hours | PEGylation, Citrate ions |

| Mesoporous Carbon | Hard templating | >30 days | >28 days | N/A (inert) |

| Gold Nanosphere | Citrate reduction | Stable | Stable | N/A (inert) |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of pH-Sensitive Polymers

| Polymer | pKa | Buffering Capacity (β) | Protonation (% at pH 5.0) | Typical EE% (siRNA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(L-histidine) (PLH) | ~6.5 | 2.8 | ~85% | 75-85% |

| Poly(β-amino ester) (PBAE) | ~6.2-6.8 | 3.1 | 90-98% | 80-92% |

| Poly(allylamine) (PAA) | ~7.5 | 4.5 | ~99% | 65-75% |

| Chitosan | ~6.3 | 2.5 | ~80% | 70-80% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Microfluidic Formation of Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) Objective: Reproducibly formulate siRNA-loaded LNPs with high encapsulation efficiency. Materials: Ionizable lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA), DSPC, Cholesterol, PEG-lipid, siRNA in citrate buffer (pH 4.0), Ethanol. Method:

- Prepare the lipid phase: Dissolve ionizable lipid, DSPC, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid at a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5 in pure ethanol to a total lipid concentration of 10 mM.

- Prepare the aqueous phase: Dilute siRNA in 25 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.0) to a concentration of 0.15 mg/mL.

- Use a staggered herringbone microfluidic mixer (or comparable chip). Set the syringe pumps.

- Set the lipid phase (ethanol) flow rate to 3 mL/min.

- Set the aqueous phase (siRNA) flow rate to 9 mL/min (FRR = 3:1, TFR = 12 mL/min).

- Mix streams in the chip, collecting the effluent in a vial.

- Immediately dialyze the resulting LNP suspension against 1X PBS (pH 7.4) for 24 hours at 4°C using a 20 kDa MWCO membrane to remove ethanol and buffer exchange.

- Filter through a 0.22 μm sterile filter. Measure particle size (PDI) by DLS and EE% by RiboGreen assay.

Protocol 2: Acid-Base Titration for Buffering Capacity (β) Objective: Determine the buffering capacity of a pH-sensitive polymer. Materials: Polymer (20 mg), 0.1 M HCl, 0.1 M NaOH, NaCl, degassed DI water, pH meter. Method:

- Dissolve polymer in 15 mL of 150 mM NaCl solution. Stir thoroughly.

- Adjust the initial solution to pH 2.0 using 0.1 M HCl.

- Titrate by adding small, known volumes (e.g., 10-20 μL) of 0.1 M NaOH under constant stirring.

- Record the stable pH reading after each addition.

- Continue until pH 10.0 is reached.

- Plot pH vs. volume of NaOH added (mmol of OH⁻). The buffering capacity (β) in the endolysosomal range (pH 4.5-7.4) is calculated as ΔOH⁻ / ΔpH, where ΔOH⁻ is the moles of base added per gram of polymer.

Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for LNP Formulation & Testing

Endolysosomal Escape Pathways for Different Materials

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for pH-Resistant Nanoparticle Research

| Item | Function & Key Property | Example Product/Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Cationic Lipid | Enables siRNA complexation & pH-dependent endosomal escape. pKa ~6-7. | DLin-MC3-DMA (MedChemExpress HY-108678) |

| Fusogenic Helper Lipid | Promotes membrane fusion/destabilization in acidic pH. | DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) (Avanti 850725) |

| PEGylated Lipid | Provides steric stabilization, reduces aggregation, tunes circulation time. | DMG-PEG 2000 (Avanti 880151) |

| pH-Sensitive Polymer | "Proton sponge" effect; buffering leads to osmotic rupture. | Poly(β-amino ester) (PolySciTech AP 549) |

| Porous Inorganic Core | Provides high surface area, tunable degradation, and cargo loading. | Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs, 100 nm pore 4 nm) (Sigma 900689) |

| Fluorescent pH Dye | Quantifies endosomal acidification and nanoparticle localization. | LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen L7528) |

| RiboGreen Assay Kit | Quantifies free vs. encapsulated nucleic acid for EE% calculation. | Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen R11490) |

| Microfluidic Mixer | Enables reproducible, scalable nanoparticle formation via rapid mixing. | NanoAssemblr Ignite (Precision NanoSystems) |

The "Proton Sponge" Hypothesis and Polycationic Polymer Designs

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

FAQ 1: My polycationic nanoparticles (e.g., PEI, PAMAM) show poor gene transfection efficiency despite the "proton sponge" hypothesis. What could be the issue?

- Answer: The "proton sponge" effect, which theorizes buffering and osmotic swelling for endosomal escape, is often insufficient alone. Low efficiency can stem from:

- Polymer Molecular Weight & Branching: Low MW linear polymers have weak buffering capacity. Verify your polymer's specification.

- N/P Ratio: An incorrect ratio of polymer Nitrogen (N) to nucleic acid Phosphate (P) leads to incomplete complexation or excessive toxicity. Perform a gel retardation assay to optimize (see Protocol 1).

- Serum Inhibition: Serum proteins can destabilize complexes. Test efficiency in both serum-free and serum-containing media.

- Inadequate Buffering Capacity: Quantify the buffering capacity of your polymer via acid-base titration (see Protocol 2). A true "proton sponge" should have high buffering in the pH 5.0-7.2 range.

FAQ 2: How can I experimentally confirm the "proton sponge" effect and endosomal escape for my novel polymer design?

- Answer: Confirmation requires a multi-assay approach:

- Buffering Capacity Measurement (Protocol 2): A prerequisite.

- Chloride Ion Influx Assay: Use a fluorescent chloride indicator (e.g., MQAE) in cells. "Proton sponge" buffering is coupled with Cl⁻ influx; a decrease in MQAE fluorescence confirms this event.

- Endosomal Rupture Visualization: Co-deliver a fluorescent endosomal marker (e.g., dextran-Alexa Fluor 488) with your polyplex. Use live-cell imaging to track dextran release into the cytoplasm, indicating rupture.

FAQ 3: My nanoparticles are cytotoxic. How can I modify polycationic designs to reduce toxicity while maintaining endolysosomal escape?

- Answer: Cytotoxicity is a major hurdle. Implement these design strategies:

- Biodegradable Linkages: Incorporate esters or disulfides that cleave in the reducing cytosolic environment.

- PEGylation: Shield positive charges with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to reduce non-specific interactions.

- Hydroxyl Modification: Replace some amines with hydroxyl groups (e.g., generating poly(β-amino ester)s) to lower charge density.

- Titration Toxicity Assay: Always perform a dose-response cytotoxicity assay (e.g., MTT, LDH) alongside transfection experiments to identify the optimal therapeutic window.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Agarose Gel Retardation Assay for Optimal N/P Ratio Determination

- Prepare polyplexes at N/P ratios from 0.5 to 10 in nuclease-free buffer.

- Incubate for 30 min at room temperature.

- Load samples onto a 1% agarose gel containing a safe DNA stain. Run at 80-100 V for 45-60 min in TAE buffer.

- Visualize under UV light. The optimal N/P ratio is the lowest ratio at which nucleic acid migration is completely retarded, indicating full complexation.

Protocol 2: Acid-Base Titration for Buffering Capacity Assessment

- Dissolve your polycationic polymer (e.g., 5 mg) in 15 mL of 150 mM NaCl.

- Bubble the solution with nitrogen gas to remove dissolved CO₂.

- Adjust the solution to pH 2.0 using 0.1 M HCl.

- Titrate by adding small aliquots (e.g., 10 µL) of 0.1 M NaOH under constant stirring.

- Record the pH after each addition until pH 12 is reached.

- Plot pH vs. volume of NaOH. Calculate the buffering capacity (β) in the endolysosomal range (pH 5.0-7.2) using the formula: β = ΔOH⁻ / ΔpH. Compare to a known standard like branched PEI (25 kDa).

Table 1: Comparison of Common Polycationic Polymers in "Proton Sponge" Context

| Polymer | Typical MW (kDa) | pKa Range | Buffering Capacity (pH 5-7.2) | Relative Transfection Efficiency | Common Cytotoxicity Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branched PEI | 25 | ~4.5-9.0 | High | High (Gold Standard) | High; membrane damage, apoptosis. |

| Linear PEI | 25 | ~6.5-8.5 | Moderate | Moderate-High | Lower than branched, but still significant. |

| PAMAM Dendrimer (G5) | ~28 | 3.9 & 6.9 | Moderate (Bimodal) | Moderate | Concentration-dependent hemolysis. |

| Poly(β-amino ester) | Varies | ~6.0-7.0 | Tunable (Moderate) | Low-High (Tunable) | Generally lower; depends on monomer. |

| Chitosan | 10-150 | ~6.5 | Very Low | Low | Very Low. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide: Symptoms, Causes, and Solutions

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No transfection | Polyplex instability, incorrect N/P ratio | Perform gel retardation assay. Increase N/P ratio systematically. |

| High cytotoxicity, good transfection | Excessive positive charge, non-degradable polymer | Modify polymer with PEG or degradable links. Reduce N/P ratio. |

| Efficiency drops with serum | Serum protein adsorption | Incorporate stealth PEG chains or target-specific ligands. |

| Endosomal trapping observed | Weak "proton sponge" effect | Redesign polymer to increase buffering in pH 5-7.2 range. |

Visualizations

Experimental Workflow for Proton Sponge Mechanism

Endosomal Escape vs Degradation Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Role in Hypothesis Testing |

|---|---|

| Branched PEI (25 kDa) | Gold standard positive control for "proton sponge" effect due to its high buffering capacity. |

| Chloride Indicator (MQAE) | Fluorescent probe to confirm Cl⁻ influx accompanying proton buffering, a key event in the hypothesis. |

| Lysosomotropic Dye (e.g., LysoTracker) | Fluorescent dye that accumulates in acidic organelles to label endolysosomal compartments for co-localization studies. |

| Fluorescent Dextran (70 kDa, Alexa Fluor 488) | Fluid-phase endocytosis marker. Its release from endosomes upon polyplex co-delivery visualizes rupture/escape. |

| MTT/XTT/CellTiter-Glo Assay Kits | For quantifying cell viability/cytotoxicity after polyplex treatment, a critical parameter for polymer design. |

| Heparin Sodium Salt | Competitive polyanion used to dissociate polyplexes in release assays, confirming electrostatic complexation. |

| Poly(β-amino ester) Library | Tunable, often biodegradable polymers for testing structure-activity relationships of buffering and escape. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor that blocks endosomal acidification. Used as a negative control to inhibit "proton sponge" dependent escape. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Context: This support center is designed to assist researchers working on stabilizing nanoparticles against recognition and clearance, particularly within a thesis framework focused on overcoming nanoparticle instability in endolysosomal pH environments for drug delivery applications.

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: During in vivo experiments, my PEGylated nanoparticles still show significant clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). What are the potential causes? A: This is a common issue. Primary causes and solutions are:

- Low PEG Density or Poor Conformation: A low grafting density (<10-20 PEG chains per 100 nm²) or short chain length (<2 kDa) can lead to a "mushroom" conformation, failing to provide effective steric shielding. Solution: Optimize PEG:nanoparticle ratio during synthesis and characterize surface density using techniques like NMR or fluorescence assays. Shift to higher molecular weight PEG (e.g., 5 kDa) for a more stable "brush" conformation.

- PEG Degradation in Acidic Endolysosomes: Your thesis context is key. PEG can undergo acid-catalyzed hydrolysis at endolysosomal pH (4.5-5.0), leading to deshielding. Solution: Consider using pH-stable stealth polymers (e.g., poly(2-oxazoline)s) or supplement PEGylation with pH-responsive coatings that only shed inside the target compartment.

- Protein Corona Formation: PEG can still adsorb certain proteins, leading to opsonization. Solution: Ensure rigorous purification to remove synthesis reagents and consider incorporating a minimal fraction of targeting ligands to reduce non-specific adsorption.

Q2: My stealth-coated nanoparticles aggregate when incubated in endolysosomal pH buffer (pH 4.5-5.0). How can I diagnose and fix this? A: Aggregation at low pH indicates coating instability.

- Diagnosis: Perform Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and zeta potential measurements across a pH gradient (7.4 to 5.0). A sharp drop in zeta potential magnitude or a sudden increase in polydispersity index (PDI) pinpoints the pH of destabilization.

- Potential Fixes:

- Use a denser PEG brush or a PEG-lipid conjugate with higher anchoring strength.

- Employ a co-functionalization strategy with a small, charged molecule (e.g., anionic carboxylates) to enhance electrostatic repulsion at low pH.

- Switch to a zwitterionic coating (e.g., poly(carboxybetaine)), which maintains stability across a wide pH range.

Q3: What are the best methods to quantitatively confirm the successful attachment and surface density of PEG or stealth polymers on my nanoparticles? A: Reliable quantification is critical for reproducibility. Common methods are summarized below:

Table 1: Methods for Characterizing Stealth Coating Density

| Method | Principle | Information Obtained | Typical Protocol Outline |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1H NMR Spectroscopy | Quantifies unique PEG polymer protons vs. nanoparticle core signals. | Grafting density, confirmation of covalent attachment. | 1. Dissolve purified NP in deuterated solvent. 2. Record 1H NMR spectrum. 3. Integrate characteristic peak (e.g., PEG -OCH2- at ~3.6 ppm) vs. core reference peak. Calculate density using known NP concentration and surface area. |

| Fluorometric Assay | Uses fluorescence-tagged PEG polymers or a dye that complexes with PEG. | Relative or absolute surface density. | For tagged PEG: 1. Synthesize NPs with FITC-PEG. 2. Measure fluorescence after purification. 3. Compare to a standard curve of free FITC-PEG. For complexation: Use iodine/baicalin assay. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Measures weight loss of organic coating upon heating. | Mass fraction of organic coating, approximate grafting density. | 1. Dry NP sample thoroughly. 2. Heat from 25°C to 600°C under N2. 3. Weight loss step corresponds to PEG/degradation. Calculate mass % and derive density. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Measures atomic composition of the top ~10 nm surface. | Surface elemental composition (C/O ratio confirms PEG presence). | 1. Deposit dry NPs on adhesive tape. 2. Irradiate with X-rays under ultra-high vacuum. 3. Analyze the binding energy of emitted electrons, focusing on C1s and O1s peaks. |

Q4: How can I experimentally prove that my stealth coating delays recognition and endolysosomal trafficking in cell studies? A: This requires a combination of cellular assays.

- Protocol: Quantitative Cellular Uptake Kinetics.

- Label: Prepare nanoparticles with a fluorescent core or dye encapsulated in the coating.

- Treat: Incubate cells (e.g., macrophages, HeLa) with stealth-coated and uncoated (control) NPs at equal particle number concentration (e.g, 100 µg/mL) for varying times (0.5, 1, 2, 4 h).

- Analyze: Use flow cytometry to measure cell-associated fluorescence. Expected Result: Stealth NPs show significantly lower fluorescence signal over time.

- Protocol: Colocalization Analysis for Endolysosomal Avoidance.

- Stain: Pre-stain cells with lysosome-specific dyes (e.g., LysoTracker Red).

- Treat: Incubate with fluorescently labeled stealth NPs for a critical time point (e.g., 4 h).

- Image: Acquire high-resolution confocal microscopy Z-stacks.

- Quantify: Use software (e.g., ImageJ) to calculate Manders' or Pearson's colocalization coefficients. Expected Result: Stealth NPs show lower coefficients, indicating reduced lysosomal trafficking.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Stealth Nanoparticle Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Role in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| mPEG-NHS Ester (e.g., 5 kDa) | Standard for amine-reactive PEGylation. Forms stable amide bonds with surface -NH2 groups on nanoparticles (e.g., aminated silica, chitosan NPs). |

| DSPE-PEG(2000)-Amine | A lipid-PEG conjugate for inserting into lipid bilayer coatings (liposomes, lipid NPs). Provides a stable anchor for the PEG brush. |

| Poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) (PMOXA) | A promising PEG-alternative stealth polymer. Offers high stability against enzymatic and acidic degradation, relevant for endolysosomal pH research. |

| LysoTracker Deep Red | A cell-permeable fluorescent dye that accumulates in acidic organelles (lysosomes). Essential for colocalization studies to track NP trafficking. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Used to create a biologically relevant protein corona in vitro by incubating with NPs. Critical for pre-conditioning NPs before cell experiments to mimic in vivo conditions. |

| pH 4.5-5.0 Citrate or Acetate Buffers | To simulate the harsh endolysosomal environment for stability and aggregation studies. Must be isotonic and used with controls at pH 7.4. |

| Iodine Solution (for Baicalin Assay) | Part of a colorimetric/fluorometric kit to indirectly quantify PEG density on nanoparticle surfaces. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Visualizations

Title: Optimization Workflow for Stealth Nanoparticle Development

Title: Cellular Recognition Pathways for Stealth Nanoparticles

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

This support center is designed for researchers working within the broader thesis context of enhancing nanoparticle stability and function in endolysosomal pH environments (pH 4.5-6.5) to achieve controlled payload release in the cytosol.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My pH-responsive linker is cleaving prematurely in the extracellular environment (pH 7.4), leading to off-target release. What could be the cause? A: This is often due to a linker pKa that is too high. The linker’s hydrolysis or cleavage rate should be minimal at pH 7.4. Check the chemical stability data of your linker (e.g., hydrazone, β-thiopropionate, vinyl ether) in neutral buffer over 24-48 hours. Consider switching to a linker with a lower pKa (closer to 5.0) or incorporating a double-cleavable linker strategy for enhanced specificity.

Q2: My nanoparticle payload is not being released efficiently in the cytosol despite using a pH-responsive linker. What should I investigate? A: The issue may lie in nanoparticle entrapment within the endolysosomal compartment. Ensure your linker's cleavage kinetics (t½) are faster than the rate of lysosomal degradation. Investigate co-functionalization with endosomolytic agents (e.g., HA2 peptides, cationic lipids) to promote endosomal escape. Confirm intracellular pH gradients using lysosomotropic pH probes like LysoSensor.

Q3: I observe high nanoparticle aggregation at endosomal pH, which complicates my release assays. How can I mitigate this? A: This instability is a key thesis challenge. Aggregation is often due to changes in surface charge or hydrophobicity upon linker protonation. Incorporate PEG spacers between the nanoparticle core and the pH-responsive linker to maintain colloidal stability. Alternatively, use pH-responsive linkages that shift charge to more positive values, which can also aid in endosomal escape via the proton sponge effect.

Q4: How do I quantitatively compare the release profiles of different linkers? A: Use a standardized in vitro release assay simulating pH progression: Buffer at pH 7.4 (2 hrs) -> pH 6.5 (2 hrs) -> pH 5.0 (4 hrs). Sample at intervals and measure payload concentration via HPLC or fluorescence. Calculate key metrics: % Release at each pH, Time to 50% release (T50), and Release Rate Constant (k). See Table 1 for a structured comparison.

Q5: My cell viability data is poor after treatment with linker-functionalized nanoparticles. Is this due to linker toxicity or incomplete release? A: Perform a controlled experiment. Test the empty nanoparticle with the linker vs. without. If toxicity remains, the linker or its degradation products may be cytotoxic. If toxicity is only with the payload, it may indicate premature, non-specific release. Consider the payload's inherent cytotoxicity and ensure the linker is stable until the target pH is reached.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro pH-Dependent Release Kinetics Assay Objective: To quantify payload release from functionalized nanoparticles across a simulated physiological pH gradient.

- Preparation: Dilute your nanoparticle sample (e.g., 1 mg/mL in PBS pH 7.4) into three separate buffered solutions (0.1 M, 37°C): Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS, pH 7.4), 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES, pH 6.5), and Acetate Buffered Saline (ABS, pH 5.0).

- Incubation: Place samples in a shaking incubator (37°C, 100 rpm). For each time point (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 h), withdraw triplicate aliquots.

- Separation: Immediately centrifuge aliquots at 100,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C to pellet nanoparticles.

- Quantification: Analyze the supernatant for released payload using a validated method (HPLC-UV/FLS, LC-MS). Calculate cumulative release percentage against a standard curve.

- Data Analysis: Plot cumulative release (%) vs. time for each pH. Fit data to appropriate kinetic models (zero-order, first-order, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to determine release mechanisms.

Protocol 2: Confocal Microscopy for Intracellular Trafficking and Release Objective: To visually confirm endosomal escape and cytosolic release of a fluorescent payload.

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells (e.g., HeLa, MCF-7) on glass-bottom dishes 24h prior.

- Treatment: Incubate cells with nanoparticles functionalized with a pH-responsive linker and a fluorescent payload (e.g., DOX, FITC) for 2-4h.

- Staining: Wash cells and incubate with LysoTracker Deep Red (75 nM) for 1h to label acidic compartments (endosomes/lysosomes). Wash again.

- Live-Cell Imaging: Image immediately using a confocal microscope with appropriate filters. Acquire Z-stacks.

- Analysis: Assess co-localization of payload fluorescence with LysoTracker signal using Manders' or Pearson's coefficient. Cytosolic release is indicated by diffuse, non-colocalized payload fluorescence.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Common pH-Responsive Linkers

| Linker Chemistry | Typical Cleavage pH (pKa) | Cleavage Mechanism | In Vitro T50 at pH 5.0* | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrazone | ~5.0-6.0 | Acid-catalyzed hydrolysis | 2-10 hours | Simple synthesis, well-characterized | Can be slow; some stability issues at pH 7.4 |

| β-Thiopropionate | ~5.5-6.5 | Intramolecular cyclization | 1-4 hours | Fast kinetics, self-immolative | Potential thiol reactivity |

| Vinyl Ether | ~4.5-5.5 | Hydrolysis | 0.5-2 hours | Very rapid at low pH, sharp transition | Sensitive to synthesis and storage |

| Acetal/Ketal | ~4.5-5.5 | Hydrolysis | 4-12 hours | Good stability at neutral pH | Hydrolysis products can be bulky |

| cis-Aconityl | ~4.5-5.0 | Hydrolysis & intramolecular | 6-24 hours | Very stable above pH 6.0 | Slower release kinetics |

*T50 (Time to 50% release) is highly dependent on specific structure, local environment, and temperature. Values represent common ranges from literature.

Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| MES Buffer (pH 6.5) | Simulates the pH of the early/sorting endosome in in vitro release assays. | Use high-purity, low-fluorescence grade for sensitive assays. |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 5.0) | Simulates the pH of late endosomes and lysosomes. | Check ionic strength compatibility with your nanoparticles. |

| LysoTracker Deep Red | A cell-permeant fluorescent dye that accumulates in acidic organelles for live-cell imaging. | Use at low nM concentrations to avoid toxicity; image promptly. |

| Chloroquine | A lysosomotropic agent used as a positive control for endosomal disruption. | Use to confirm if release/escape is the bottleneck in your system. |

| PEG-Spacer-NHS Ester | A heterobifunctional crosslinker to introduce a stability-enhancing spacer between nanoparticle and linker. | Spacer length can profoundly affect accessibility and cleavage kinetics. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | A specific V-ATPase inhibitor that prevents endosomal acidification. | Used as a negative control to prove pH-dependence of release. |

| Dialysis Membranes (MWCO) | For purification of functionalized nanoparticles and separating free payload in release studies. | Choose MWCO 3-10x smaller than nanoparticle size. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) System | To measure hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) before/after pH exposure. | Critical for monitoring pH-induced aggregation (nanoparticle instability). |

Membrane-Destabilizing Peptides and Polymers for Endosomal Escape

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQ

This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges when working with membrane-destabilizing agents to promote endosomal escape of nanoparticles, a critical component of research into nanoparticle instability in endolysosomal pH environments.

FAQs: Common Issues and Solutions

Q1: My peptide/polymer shows excellent in vitro membrane disruption but fails to induce endosomal escape in my cellular assay. What could be wrong? A: This is often a pH-sensitivity mismatch. The agent may be designed to disrupt membranes at a specific pH (e.g., lysosomal pH ~4.5), but your nanoparticles may be trapped in early endosomes (pH ~6.5-6.0). Verify the pH-responsiveness profile of your agent using a hemolysis or liposome leakage assay across a pH gradient (pH 7.4 to 4.5). Adjust the pKa or composition to match the target endosomal compartment.

Q2: I observe high cytotoxicity with my endosomolytic agent, even at doses intended for escape. How can I mitigate this? A: Cytotoxicity often stems from non-specific membrane disruption at the plasma membrane (pH 7.4). Troubleshoot using the following steps:

- Check Dose: Re-run a dose-response cytotoxicity assay (e.g., MTT, LDH) alongside a functional readout (e.g., GFP expression from delivered mRNA).

- Modify Trigger: Increase the agent's pH-sensitive selectivity. For example, modify histidine-rich peptides with more histidines to sharpen the pH-response curve.

- Change Conjugation: If conjugated to the nanoparticle, optimize the conjugation density (see Table 1). A lower density may suffice for escape while reducing surface activity.

Q3: How do I quantitatively compare the endosomal escape efficiency of different peptides or polymers? A: Use a combination of quantitative assays:

- Direct Quantification: Use a split-GFP or split-luciferase assay where complementation only occurs upon cytosolic delivery.

- Indirect Functional Readout: Measure protein expression (via flow cytometry or fluorescence) from delivered mRNA or pDNA.

- Co-localization Analysis: Quantify the decrease in co-localization of your nanoparticle with endosomal markers (e.g., Rab5, LAMP1) over time using high-content imaging. Normalize to a non-escaped control.

Q4: My polymer/nanoparticle complex aggregates at endosomal pH, leading to inconsistent results. A: Aggregation can prematurely trap complexes. This instability must be addressed per your thesis context.

- Buffer Test: Ensure your formulation buffer does not contain phosphate or other anions that can bridge complexes upon acidification.

- Polymer Modification: Incorporate hydrophilic stealth segments (e.g., PEG) or change the polymer architecture (e.g., brush vs. linear) to improve colloidal stability across pH ranges.

- Characterize Stability: Perform dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta-potential measurements on your complexes incubated in buffers mimicking endosomal pH progression.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: pH-Dependent Hemolysis Assay for Agent Characterization Purpose: To quantify the membrane-disruptive activity of a candidate peptide/polymer across a physiological pH gradient. Procedure:

- Prepare RBCs: Wash fresh human or sheep red blood cells (RBCs) 3x with PBS (pH 7.4).

- Prepare pH Buffers: Create isotonic buffers (e.g., citrate-phosphate, HEPES) at pH 7.4, 6.5, 6.0, 5.5, and 5.0.

- Incubation: Dilute RBCs to 4% v/v in each pH buffer. Add your agent at a range of concentrations (e.g., 1-50 µg/mL). Include positive (1% Triton X-100) and negative (buffer only) controls.

- Reaction: Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour with gentle mixing.

- Quantification: Centrifuge samples, measure hemoglobin release by absorbance of supernatant at 540 nm. Calculate % hemolysis = [(Sample - Negative)/(Positive - Negative)] * 100.

- Analysis: Plot % hemolysis vs. pH and determine the pH threshold for activity.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Endosomal Escape via Gal8-mCherry Recruitment Assay Purpose: A live-cell, fluorescence-based method to detect endosomal membrane disruption. Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Seed HeLa or other suitable cells stably expressing Gal8-mCherry in a glass-bottom dish.

- Treatment: Formulate your nanoparticle (e.g., polyplex, lipoplex) with the membrane-destabilizing agent and the cargo (e.g., pDNA, mRNA). Apply to cells at 60-80% confluency.

- Imaging: At 2-6 hours post-transfection, image live cells using a confocal microscope (mCherry channel). Gal8 binds exposed β-galactosides upon endosomal damage, forming bright puncta.

- Analysis: Count the number of Gal8-mCherry puncta per cell and normalize to the number of internalized nanoparticles (e.g., using a fluorescent nanoparticle label). Compare to positive (e.g., PEI) and negative (e.g., naked nanoparticle) controls.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Common Membrane-Destabilizing Agents

| Agent (Example) | Type | Mechanism of Action | Key pH-Sensitive Group | Typical Working Conc. (for escape) | Cytotoxicity Concern | Optimal Conjugation Density (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GALA Peptide | Peptide | Forms α-helix at low pH, inserts into membrane | Glutamic Acid (COOH protonation) | 10-50 µM | Low to Moderate | N/A (often co-incubated) |

| HA2 (Influenza derived) | Peptide | Fusion peptide, disrupts via hydrophobic insertion | Histidine, N-terminal Glu | 5-20 µM | Moderate | ~30-50 peptides per liposome |

| Poly(L-histidine) | Polymer | "Proton Sponge", buffering leads to rupture | Imidazole (pKa ~6.5) | 10-30 µg/mL | High at high MW | N/A (often part of backbone) |

| PLL-g-(Imidazole) | Copolymer | Combines buffering & direct disruption | Imidazole side chains | 20-40 µg/mL | Moderate | N/A |

| PEI (25k Da) | Polymer | Proton Sponge effect, osmotic swelling | Amines (primary, secondary) | 0.5-1.5 µg/µg nucleic acid | High | N/A (forms polyplexes) |

| PAsp(DET) | Polymer | Membrane fusion/perturbation at low pH | Aminoethylene in side chain | 10-25 µg/mL | Low | N/A |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Endo-Porter | A commercially available, non-peptide amphiphile used as a positive control for pH-dependent endosomal escape. |

| Chloroquine | Lysosomotropic agent used as a historical control to alkalinize endosomes and promote escape via inhibition of lysosomal enzymes. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Specific V-ATPase inhibitor that blocks endosomal acidification. Used to validate the pH-dependent mechanism of an escape agent. |

| pHrodo Dextran | Fluorescent dye whose intensity increases dramatically in acidic compartments. Used to label endosomes and monitor acidification kinetics. |

| LysoTracker Dyes | Cell-permeable fluorescent probes that accumulate in acidic organelles. Useful for staining the endolysosomal pathway. |

| β-glucuronidase Assay Kits | Used to detect lysosomal membrane permeabilization as a proxy for excessive, cytotoxic disruption. |

| HPLC-purified Peptides | Essential for obtaining peptides with correct sequence and high purity (>95%) to ensure reproducible membrane-disruptive activity. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: pH-Triggered Endosomal Escape Pathways

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Escape Agent Evaluation

Solving Real-World Problems: Optimization and Performance Tuning

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Context: This guide supports research on nanoparticle (NP) instability under endolysosomal pH conditions (pH 4.5-5.5), a critical challenge for drug delivery.

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: My DLS results show a large increase in polydispersity index (PDI) after pH incubation. What does this mean, and how can I confirm instability? A: A PDI increase (e.g., from <0.1 to >0.3) indicates heterogeneous size distribution, suggesting aggregation or degradation.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Filter Samples: Pre-filter all buffers and sample vials (0.22 µm) to remove dust.

- Run Controls: Always include a sample in neutral pH buffer as a control.

- Check Zeta Potential: Measure zeta potential before and after pH shift. A dramatic reduction (e.g., from -30 mV to ±5 mV) indicates loss of colloidal stability.

- Corroborate with TEM: Use TEM to visually distinguish between aggregation (visible clusters) and degradation (loss of structural integrity).

Q2: I observe quenching or a shift in fluorescence signal from my labeled nanoparticles at low pH. Is this due to instability or a photophysical effect? A: This requires distinction between environmental sensing and instability.

- Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Control Experiment: Perform a fluorescence scan of the free dye in both neutral and acidic buffers. A shift confirms a pH-sensitive dye.

- Centrifugation Assay: Ultracentrifuge the pH-incubated NPs (e.g., 100,000 x g, 30 min). If fluorescence is now in the supernatant, the dye has been released due to NP disintegration.

- FRET Confirmation: If using a FRET pair, loss of FRET efficiency after pH incubation is a strong indicator of particle disassembly and increased donor-acceptor distance.

Q3: My TEM images after acidic incubation show ambiguous structures. How do I properly prepare samples to avoid artifacts? A: TEM sample prep is critical for accurate interpretation.

- Optimized Protocol for pH-Treated NPs:

- Immediate Fixation: After pH incubation, immediately add a buffered glutaraldehyde solution (1% final conc.) to fix the structures. Let it stand for 1 hour at 4°C.