Overcoming the Hurdle: Advanced Strategies to Reduce Nanoparticle Immunogenicity in Therapeutics

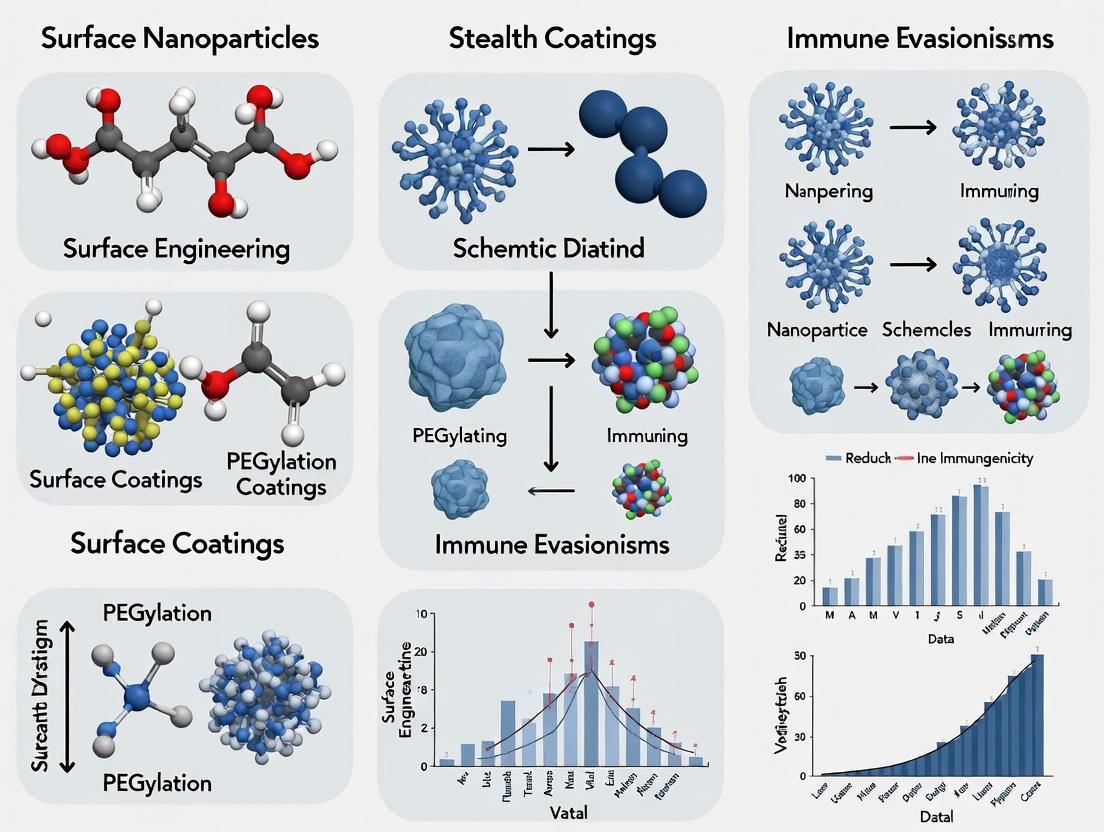

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest strategies to mitigate the immunogenicity of nanoparticles, a critical challenge in nanomedicine development.

Overcoming the Hurdle: Advanced Strategies to Reduce Nanoparticle Immunogenicity in Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest strategies to mitigate the immunogenicity of nanoparticles, a critical challenge in nanomedicine development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational immune mechanisms, details cutting-edge methodological approaches like polymer engineering and novel LNP design, and addresses key troubleshooting areas such as anti-PEG antibodies. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with applied techniques, optimization challenges, and comparative validation data from recent studies, this review serves as a strategic guide for developing safer and more effective nanotherapeutic platforms, from vaccines to cancer therapies.

Understanding the Enemy: Foundational Immune Responses to Nanoparticles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is immunogenicity in the context of biologic drugs? Immunogenicity refers to the ability of a therapeutic drug, particularly biologic proteins like monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), to provoke an unwanted immune response in the patient. This response manifests as the production of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) that can recognize and bind to the therapeutic agent [1] [2] [3].

2. What are Anti-Drug Antibodies (ADAs)? Anti-drug antibodies are host-generated antibodies that specifically target a biologic therapeutic. They form when the patient's immune system recognizes all or part of the biologic drug as foreign [1] [3]. ADAs can develop against any biologic, including fully human monoclonal antibodies [4].

3. What are the clinical consequences of ADA formation? The development of ADAs can lead to several significant clinical consequences [1] [3] [5]:

- Reduced Drug Efficacy: ADAs can neutralize the therapeutic effects of the drug, rendering it less effective or completely ineffective.

- Altered Pharmacokinetics: ADAs often increase the clearance of the drug from the bloodstream, leading to lower drug concentrations.

- Adverse Events: ADA formation can cause hypersensitivity reactions, infusion-related reactions, and in severe cases, anaphylaxis.

4. How are ADAs detected and measured? Immunogenicity is typically assessed using a multi-tiered testing approach [5]:

- Tier 1 (Screening): An assay designed to minimize false-negative results.

- Tier 2 (Confirmation): A more specific assay to minimize false-positives.

- Tier 3 (Characterization): Assays to further characterize the ADAs, such as determining their neutralizing capability. Common analytical platforms include ligand-binding immunoassays, homogenous mobility-shift assays, and surface plasmon resonance [5].

5. Can the immunogenicity of nanoparticles be managed? Yes, nanotechnology offers promising strategies to modulate immune responses. Nanoparticles can be engineered with specific surface properties or co-administered with immunosuppressive agents to reduce their immunogenic potential. Research is focused on designing tolerogenic nanoparticles that can evade immune recognition or induce antigen-specific tolerance [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges in Immunogenicity Assessment

Problem 1: Lack of Assay Window in TR-FRET-based ADA Detection

Issue: The assay shows no difference in signal between positive and negative controls.

Recommendations:

- Instrument Setup: Verify that the microplate reader is configured correctly. The most common reason for a failed TR-FRET assay is the use of incorrect emission filters. Always use the manufacturer-recommended filters for your specific instrument model [6].

- Reagent Preparation: Differences in prepared stock solutions, typically at 1 mM, are a primary reason for variations in EC50/IC50 values between labs. Ensure consistent and accurate reagent preparation [6].

- Internal Reference: For TR-FRET assays, always use a ratiometric data analysis (acceptor signal/donor signal). The donor signal serves as an internal reference, accounting for pipetting variances and lot-to-lot reagent variability [6].

Problem 2: High Background Noise in Immunoassays

Issue: Non-specific binding leads to high background, obscuring the true signal.

Recommendations:

- Assay Robustness: Evaluate the Z'-factor of your assay. This statistical parameter assesses the quality and robustness of an assay by considering both the assay window (difference between max and min signals) and the data variation (standard deviation). A Z'-factor > 0.5 is considered suitable for screening [6].

- Positive Controls: Be aware that immunogenicity assays are semi-quantitative and rely on positive controls (ADAs often created in non-human species). These can differ from human ADAs and may contribute to variability. Results from different assays or for different therapeutics are not directly comparable [5].

Key Signaling Pathways in Immunogenicity

T-Cell Dependent Pathway of ADA Formation

This is the primary pathway for high-affinity, persistent ADA responses. The following diagram illustrates the cellular and molecular interactions.

Innate Immune Recognition of Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)

Nanoparticle-based delivery systems, like LNPs, can stimulate innate immunity, which in turn influences adaptive immune responses. The diagram below outlines key recognition pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Validating TR-FRET Assay Performance

This protocol is critical for ensuring your assay is functioning correctly before testing samples [6].

Instrument Check:

- Use your purchased assay reagents to test the microplate reader's TR-FRET setup.

- Confirm the correct excitation and emission filters are installed as per the instrument compatibility guide.

Development Reaction Test (If Applicable):

- 100% Phosphopeptide Control: Do not expose to development reagent. This should yield the lowest ratio value.

- Substrate (0% Phosphopeptide): Expose to a 10-fold higher concentration of development reagent than recommended. This should yield the highest ratio value.

- A properly developed assay should show a 10-fold difference in the ratio between the 100% phosphorylated control and the substrate.

Protocol 2: Three-Tiered Immunogenicity Testing Approach

This is the standard framework for assessing immunogenicity during drug development [5].

Tier 1 - Screening Assay:

- Objective: Identify potentially positive samples with high sensitivity to minimize false negatives.

- Method: Typically a ligand-binding immunoassay (e.g., ELISA, bridging assay).

- Output: A signal cut-point is established to classify samples as "negative" or "potentially positive."

Tier 2 - Confirmatory Assay:

- Objective: Confirm the specificity of potentially positive samples by minimizing false positives.

- Method: The screening assay is repeated with and without excess free drug. A significant reduction in signal in the presence of the drug confirms specificity for the therapeutic.

- Output: Samples are confirmed as "ADA-positive."

Tier 3 - Characterization Assay:

- Objective: Further characterize the confirmed ADA response.

- Methods:

- Neutralizing Assay: Determines if the ADAs can block the biological activity of the therapeutic drug (e.g., a cell-based reporter assay).

- Isotyping: Determines the isotope of the ADA (e.g., IgG, IgM).

- Output: Data on the neutralizing capacity and class of the ADA response.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their functions in immunogenicity research.

| Research Reagent | Function in Immunogenicity Research |

|---|---|

| LanthaScreen TR-FRET Reagents | Used in competitive binding and ADA detection assays; time-resolved fluorescence reduces background noise [6]. |

| Positive Control ADA | Species-specific anti-drug antibody used to validate and calibrate immunogenicity assays [5]. |

| Pattern Recognition Receptor (PRR) Agonists/Antagonists | Tools to study innate immune activation by nanoparticles (e.g., TLR ligands, STING agonists) [7]. |

| Cytokine Detection Kits (e.g., IL-6, TNFα, IFN-γ) | Measure pro-inflammatory cytokine release following immune cell activation by therapeutics or nanoparticles [7]. |

| MHC-II Tetramers | Identify and characterize T-cell populations specific to drug-derived peptides [4]. |

| Tolerogenic Nanoparticles | Engineered particles designed to deliver antigens in a way that induces immune tolerance rather than activation [4]. |

Quantitative Data on Immunogenicity and ADA Impact

Reported Immunogenicity Rates of Selected Monoclonal Antibodies

Table: Immunogenicity incidence for a selection of therapeutic mAbs. [1]

| International Non-proprietary Name | Brand Name | Target | Format | % ADA (Reported Incidence) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab | Humira | TNFα | Human IgG1 | 28% |

| Alemtuzumab | Lemtrada | CD52 | Humanized IgG1 | 67.1–75.4% |

| Bevacizumab | Avastin | VEGF | Humanized IgG1 | 0% |

| Atezolizumab | Tecentriq | PD-L1 | Humanized IgG1 | 30–48% |

| Cetuximab | Erbitux | EGFR | Chimeric IgG1 | Data in source |

Strategies for Mitigating Immunogenicity

Table: Approaches to reduce the immunogenicity of biologic therapeutics. [1] [4] [3]

| Mitigation Strategy | Core Principle | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Engineering (De-immunization) | Identify and remove immunogenic T-cell and B-cell epitopes from the therapeutic protein while maintaining activity. | Humanization of murine antibodies; in silico prediction and removal of T-cell epitopes. |

| Glycoengineering | Modify glycosylation patterns to match human-like profiles, avoiding non-human glycan structures. | Production in CHO cells to avoid immunogenic α-1,3-galactose epitopes present in murine cell lines. |

| Conjugation with Polymers | Shield immunogenic epitopes on the protein surface with bulky, hydrophilic polymers. | PEGylation (though this can sometimes introduce new immunogenic epitopes). |

| Nanotechnology-Based Delivery | Use nanoparticles to encapsulate the biologic, altering its biodistribution and interaction with the immune system. | Tolerogenic nanoparticles; synthetic vaccine particles (SVPs). |

| Immune Tolerance Induction | Use high-dose or co-therapy protocols to induce antigen-specific tolerance in the patient. | Combination therapy with immunomodulators (e.g., methotrexate). |

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as the leading delivery platform for mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. Their effectiveness hinges on the ability to activate the immune system, a double-edged sword that enables robust vaccine efficacy but can also lead to adverse effects and reduced therapeutic potency in non-vaccine applications. Understanding the precise immune recognition pathways is therefore fundamental for optimizing LNP design, particularly for a thesis focused on strategies to reduce nanoparticle immunogenicity. This guide provides a technical deep-dive into these pathways, with troubleshooting FAQs and experimental protocols for researchers.

FAQ: Mechanisms of LNP-Induced Immune Activation

What are the key components of LNPs that contribute to their immunogenicity?

LNPs are complex entities composed of four main lipid components, each playing a distinct role in immunogenicity:

- Ionizable Lipid: Crucial for encapsulating mRNA and facilitating endosomal escape. Its structure can trigger innate immune signals, often in an IL-6 dependent manner [8] [7].

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-Lipid: Provides a "stealth" coating to enhance circulation time. However, PEG can be immunogenic, leading to anti-PEG antibody production that accelerates blood clearance of subsequent doses [7] [9].

- Phospholipid and Cholesterol: Primarily structural components that stabilize the LNP. They can also contribute to adjuvanticity and aid in endosomal escape [7].

Is the immune activation driven by the LNP carrier, the mRNA payload, or both?

Both components contribute, but they activate distinct and complementary arms of the innate immune system [10].

- LNP Component: Primarily triggers a strong pro-inflammatory response in stromal cells (e.g., fibroblasts, endothelial cells) at the injection site. This is characterized by the production of cytokines like IL-6, TNFα, and CCL2 [8] [10].

- mRNA Component: Essential for inducing a potent type I interferon (IFN) response, specifically IFN-β. This response is dependent on signaling through the type I interferon receptor (IFNAR) and is dominant in migratory dendritic cells (mDCs) [8] [10].

Single-cell transcriptomic studies have shown that the LNP-induced pro-inflammatory axis and the mRNA-induced IFN-axis are distinct, with the latter being critical for driving potent cellular immunity [10].

How does LNP and mRNA recognition bridge innate and adaptive immunity?

The innate immune activation creates an inflammatory context that directs the adaptive immune response.

- Antigen Presentation: Dendritic cells (DCs) are activated at the injection site, where they uptake the translated antigen, mature, and migrate to draining lymph nodes [8] [7].

- T-cell Priming: In the lymph nodes, mature DCs present the antigen to naïve T cells. The cytokines produced during the innate phase (e.g., type I IFNs, IL-6) help shape the T-cell response, promoting the differentiation of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [7].

- B-cell Activation and Antibody Production: The activated immune environment, particularly the help from T cells (T-follicular helper cells), supports B-cell activation in germinal centers, leading to the production of high-affinity, antigen-specific antibodies [7].

What are the common experimental challenges when studying LNP immunogenicity?

| Challenge | Underlying Cause | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Cytokine Release | Potent activation of monocytes/macrophages and DCs by both LNP and mRNA [11]. | Use nucleoside-modified mRNA; pre-treat with IFNAR blocking antibodies [8]. |

| Anti-PEG Antibodies | Immune recognition of PEG polymer, leading to accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon [9]. | Use alternative PEG-lipids (e.g., branched, cleavable) or PEG replacements like PCB lipids [9]. |

| Variable Efficacy in Repeated Dosing | Primarily due to anti-PEG antibodies or immune memory against the LNP itself [9]. | Employ LNP formulations with lower immunogenicity profiles, such as those using HO-PEG lipids or PCB lipids [9]. |

| Translation Inhibition | Type I IFN signaling activates PKR, which phosphorylates eIF2α, suppressing overall protein translation and antigen production [7]. | Implement transient IFNAR blockade to enhance antigen expression and adaptive immunity [8]. |

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Differentiating LNP vs. mRNA-Driven Immune Responses

Problem: An experimental LNP-mRNA vaccine shows strong innate activation, but the relative contributions of the carrier and payload are unknown.

Solution: Employ a factorial experimental design to dissect the components.

Experimental Workflow:

Detailed Protocol:

- Formulation: Prepare four formulations as outlined in the workflow above. The "non-coding mRNA" control should use a sequence that does not encode a functional protein [8].

- Animal Immunization: Administer formulations to age-matched C57BL/6J mice (6-8 weeks old) via intramuscular injection (e.g., 50 μL per hind leg) [8].

- Sample Collection: At defined time points (e.g., 2, 16, 40 hours post-injection), resect the injection site (muscle tissue) and draining lymph nodes (dLNs) [10].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Process tissues to create single-cell suspensions. Perform scRNA-seq to create a transcriptomic atlas. Key analyses include:

- Validation: Validate findings using cytokine ELISAs (for IL-6, TNFα, IFN-β) and flow cytometry for activation markers (CD69 on T/NK cells, CD80/86 on DCs) [10] [11].

Guide 2: Modulating Type I Interferon Signaling to Enhance Efficacy

Problem: Strong innate immune activation, particularly the type I IFN response, is inhibiting antigen translation and attenuating the desired adaptive immune response.

Solution: Implement a transient blockade of the IFN-α/β receptor (IFNAR) signaling.

Experimental Workflow:

Detailed Protocol:

- IFNAR Blocking: Inject mice intraperitoneally with 2.5 mg of anti-IFNAR monoclonal antibody (e.g., clone I-401 from Leinco Technologies) 24 hours before immunization [8].

- Vaccination: Immunize mice with the LNP-mRNA vaccine as per your standard protocol.

- Reinforce Blockade: Administer a second dose of anti-IFNAR mAb (2.5 mg, i.p.) 24 hours after immunization [8].

- Assessment of Adaptive Immunity:

- Cellular Immunity: 7-14 days post-vaccination, isolate splenocytes or lymph node cells. Measure antigen-specific CD8+ T cells using MHC-I tetramers or intracellular cytokine staining after peptide stimulation [8].

- Humoral Immunity: Collect serum and measure antigen-specific antibody titers (e.g., total IgG, IgG subclasses) via ELISA [8].

- Expected Outcome: The transient IFNAR blockade should result in significantly increased frequencies of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and elevated antibody titers compared to the isotype-control treated group [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential materials and their functions for studying LNP immunogenicity, as cited in the literature.

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example & Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-IFNAR mAb | Blocks type I interferon receptor signaling to dissect its role in attenuating adaptive immunity. | Clone I-401 (Leinco Technologies) [8]. |

| Nucleoside-modified mRNA | Base modification (e.g., N1-methyl-pseudouridine) reduces innate immune recognition and enhances antigen translation. | TriLink BioTechnologies [8]. |

| Ionizable Lipids | Key LNP component for RNA encapsulation and endosomal escape; different structures vary in immunogenicity. | ALC-0315 (Cayman Chemical) [8]. |

| PEG Lipids | Provides stealth properties; target for immunogenicity studies and engineering. | DMG-PEG 2000 (Avanti Polar Lipids) [8]. |

| HO-PEG Lipids | Hydroxyl-terminated PEG lipid with lower immunogenicity, used in clinical-stage LNPs. | OL-56 (Moderna formulations) [9]. |

| Poly(carboxybetaine) Lipids | PEG替代品;提供隐形特性,同时增强内体逃逸并减少抗聚合物抗体。 | PCB lipids (as described in Cornell study) [9]. |

| Deucravacitinib | TYK2 inhibitor; used to inhibit the JAK-STAT pathway downstream of IFNAR. | MedKoo Biosciences [8]. |

Core Immune Signaling Pathways Activated by LNPs

The following diagram synthesizes the key innate and adaptive immune pathways triggered by LNP-mRNA vaccines, integrating the roles of both the LNP and mRNA components.

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequent Issues in LNP Immunogenicity Profiling

Q1: Our LNP formulations are triggering unexpectedly high levels of anti-PEG antibodies in animal models. What factors should we investigate?

A: The induction of anti-PEG antibodies is a dose- and time-dependent process [12]. Key factors to investigate include:

- PEG-lipid molar ratio: The molar content of PEG-lipid in the LNP formulation is a critical parameter. Higher molar ratios (e.g., ≥ 3–5 mol%) can paradoxically reduce cellular uptake and translation efficiency but also influence immunogenicity [13] [14].

- PEG chain length: The immunogenicity risk appears biphasic relative to PEG length, with both very short and very long PEG chains being more likely to induce the Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) phenomenon [15].

- Lipid anchor structure: PEG-lipids with shorter, C14 lipid tails (e.g., ALC-0159, DMG-PEG) are designed for rapid dissociation from the LNP in vivo, which can enhance cellular uptake but also impact antibody production [13] [16]. Lipids with C18 tails (e.g., DSPE-PEG) have longer half-lives and different immunogenic profiles [13].

Q2: We are observing the Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) phenomenon upon repeated dosing of our PEGylated LNPs. What is the mechanism and how can it be mitigated?

A: The ABC phenomenon is an immunogenic response where a first dose of PEGylated LNPs induces anti-PEG IgM antibodies, which then bind to a subsequent dose, leading to its rapid clearance by immune cells in the liver and spleen [17] [15]. This is primarily mediated by the anti-PEG IgM triggering complement activation and enhanced phagocytosis [18].

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Modify PEG density: Both very low and very high PEG densities can reduce the ABC phenomenon. An optimal, intermediate density must be determined empirically [15].

- Use alternative PEG architectures: Branched PEG-lipid conjugates can confer better "stealth" properties than linear PEGs [15].

- Explore PEG alternatives: Polymers like poly(oxazoline), polyvinyl alcohol, and poly(glycerol) are being investigated to overcome PEG-specific immunogenicity, though none have yet proven superior in all aspects [15].

Q3: Our mRNA-LNP vaccine shows excellent protein expression in vitro but poor immunogenicity in vivo. Could the PEG be causing this?

A: Yes, this could be related to the "PEG dilemma." While PEGylation prevents nanoparticle aggregation and prolongs circulation, it can also impede cellular uptake and endosomal escape, which are crucial for mRNA delivery and subsequent immune activation [13]. To resolve this:

- Optimize the PEG-lipid molar ratio: Lowering the molar ratio of PEG-lipid (e.g., to 1.5% or less) can enhance cellular uptake and mRNA translation efficiency, potentially improving antigen presentation and immunogenicity [13] [19].

- Select a dissociable PEG-lipid: Using PEG-lipids with shorter lipid anchors (e.g., C14 tails like in ALC-0159) allows the PEG to shed more rapidly after administration, facilitating better interaction with and uptake by immune cells [13] [16].

Q4: Some of our LNP formulations appear to activate the complement system, leading to concerns about hypersensitivity. What is the link between LNPs and complement activation?

A: This is likely the CARPA (Complement Activation-Related PseudoAllergy) phenomenon. PEGylated nanoparticles can activate the complement system via the classical and/or lectin pathways, leading to the production of anaphylatoxins (C3a, C5a) that cause pseudoallergic reactions [18] [15]. Factors that increase this risk include:

- Surface charge: PEGylated carriers with negatively charged phospholipids can stimulate complement activation to a greater extent than uncharged vesicles [15].

- PEG properties: Both PEG chain length and density influence complement activation [15].

Experimental Protocols: Key Assays for Immunogenicity Assessment

Protocol 1: Quantifying Anti-PEG Antibody Production

This protocol is adapted from studies that characterized the time- and dose-dependent induction of anti-PEG antibodies following LNP administration in a rat model [12].

1. Objective: To measure the level and persistence of anti-PEG IgM and IgG in serum after LNP injection.

2. Materials:

- Animals: Wistar rats (or other suitable model).

- Test Articles: LNP formulation (e.g., based on the Comirnaty composition: ionizable lipid ALC-0315, DSPC, cholesterol, PEG-lipid ALC-0159).

- Dosing: Administer via intramuscular injection at clinically relevant doses. The study should include at least two injections, spaced 21 days apart, to model prime-boost vaccination [12].

- ELISA Reagents:

3. Procedure:

- Immunization and Serum Collection: Inject rats with the LNP formulation on Day 0 and Day 21. Collect blood serum at multiple time points (e.g., Days 0, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, 23, 25, 28, 35, 42, 49) to profile the kinetic immune response [12].

- ELISA:

- Coat ELISA plates with PEG-BSA overnight.

- Block plates with a protein-based blocking buffer.

- Add serum samples and anti-PEG antibody standards in serial dilutions.

- Incubate, then wash.

- Add HRP-conjugated detection antibody (anti-rat IgM or IgG).

- Incubate, wash, and add TMB substrate.

- Stop the reaction and read the absorbance.

- Quality Control: Ensure the intra-assay precision (Coefficient of Variation, CV%) for standards and samples is below 10%, and the coefficient of determination (R²) of the standard curve is >0.99 [12].

4. Data Analysis: Analyze the data using a Linear Mixed Model (LMM) to evaluate changes in antibody levels over time and differences across dose groups. The results will show a dose-dependent increase in anti-PEG IgM, with a booster shot leading to a rapid and enhanced response [12].

Protocol 2: Evaluating the ABC Phenomenon

1. Objective: To assess the impact of pre-existing anti-PEG immunity on the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of a second LNP dose.

2. Materials:

- Animals: Mice or rats.

- First dose ("Priming dose"): Empty PEGylated liposomes (PEG-Lip) or therapeutic LNP administered intravenously to induce anti-PEG IgM [14].

- Second dose ("Challenging dose"): PEGylated mRNA-LNP containing a reporter gene (e.g., luciferase or fluorescently labeled) administered intramuscularly or intravenously.

3. Procedure:

- Priming: Inject animals i.v. with the priming dose. A control group receives a non-PEGylated formulation or buffer.

- Confirmation of Anti-PEG IgM: Collect serum at Day 5-7 post-priming to confirm anti-PEG IgM production via ELISA [14].

- Challenging: Administer the challenging dose at the peak of anti-PEG IgM production (e.g., Day 7).

- Analysis:

- Blood Clearance: Collect blood at various time points post-injection and measure the concentration of the LNP or its payload. The ABC phenomenon is characterized by significantly accelerated clearance of the challenging dose in primed animals [17] [14].

- Biodistribution: Image animals (if using a reporter) or harvest organs (liver, spleen, injection site) at endpoint to quantify LNP distribution. Pre-existing anti-PEG IgM typically leads to increased accumulation in the liver and spleen via Kupffer cell uptake [14].

Signaling Pathways in LNP-Induced Immune Activation

The following diagram illustrates the key innate immune pathways activated by mRNA-LNPs, which subsequently shape the adaptive immune response.

Quantitative Data on LNP Immunogenicity

| Phospholipid Dose | First Injection (Prime) | Second Injection (Boost) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (L-LNP)0.009 mg/kg | Detectable on Day 3 and 5 only. | Detected at more time points. | Weak and transient response. |

| Middle (M-LNP)0.342 mg/kg | Persistent, higher levels from Day 5-21. | Constantly induced throughout Day 21-49. | Clear dose- and time-dependency. |

| High (H-LNP)2.358 mg/kg | Most persistent and highest levels from Day 5-21. | Constantly induced at the highest levels. | Fastest rate of anti-PEG IgM production. |

| Parameter | Impact on LNP Properties & Immunogenicity |

|---|---|

| Molar Content | Low (e.g., 0.5-1.5%): Faster cellular uptake, enhanced mRNA translation, but may influence stability. [13] [19]High (e.g., ≥3-5%): Reduced cellular uptake and protein expression ("PEG dilemma"); can influence anti-PEG antibody levels. [13] [14] |

| Lipid Tail Length | C14 (e.g., DMG-PEG, ALC-0159): Rapid dissociation, enhances uptake, influences immunogenicity profile. [13] [16]C18 (e.g., DSPE-PEG): Slower dissociation, longer circulation half-life, different immunogenic profile. [13] |

| PEG Chain Length | Biphasic risk: Both very short and very long chains are more likely to induce the ABC phenomenon. [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., ALC-0315, SM-102) | Critical for mRNA encapsulation during formulation and facilitating endosomal escape post-cellular uptake. Their positive charge at acidic pH enables disruption of the endosomal membrane. [7] [13] |

| Phospholipids (e.g., DSPC) | Acts as a helper lipid to stabilize the LNP structure and support the ionizable lipid in promoting membrane fusion and endosomal escape. [7] [13] |

| Cholesterol | Integrates into the LNP bilayer to modulate fluidity and rigidity, enhancing the stability and integrity of the nanoparticle. [7] [13] |

| PEG-Lipids (e.g., ALC-0159, DMG-PEG) | Provides a hydrophilic surface coating that stabilizes LNPs during formulation (prevents aggregation), reduces opsonization by serum proteins, and prolongs circulation time. The choice of lipid anchor (e.g., C14 vs C18) dictates its dissociation rate and subsequent cellular interactions. [7] [13] [16] |

| PEG-BSA Conjugate | Essential for coating ELISA plates to reliably detect and quantify anti-PEG antibodies in serum samples. [12] [17] |

| Complement Assay Kits | Used to measure complement activation (e.g., C3a, C5a, SC5b-9 levels) to assess the potential for CARPA. [18] [15] |

T-cell Dependent vs. T-cell Independent ADA Formation Mechanisms

FAQs: Understanding Anti-Drug Antibody Formation

What are Anti-Drug Antibodies (ADAs) and why are they a problem?

Anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) are immune proteins the host produces when it recognizes a biologic therapeutic, such as a monoclonal antibody (mAb), as foreign [20]. These ADAs can bind to the therapeutic mAb, leading to:

- Reduced Drug Efficacy: ADAs can neutralize the therapeutic effect or increase the drug's clearance from the body, lowering its concentration [20] [21].

- Altered Pharmacokinetics: Enhanced clearance can shorten the drug's circulation time [22].

- Safety Risks: ADA formation can cause adverse events, including hypersensitivity reactions and anaphylaxis [20] [21].

What is the fundamental difference between the two ADA formation pathways?

The key difference lies in the requirement for help from CD4+ T-cells.

- The T-cell Dependent (TD) pathway requires CD4+ T-cell co-stimulation to initiate antibody production by B cells. This pathway typically generates long-lasting, high-affinity IgG antibodies [23].

- The T-cell Independent (TI) pathway does not require help from CD4+ T-cells. B cells are activated autonomously, leading to the production of lower-affinity IgM antibodies with a shorter half-life [20] [23].

Which pathway is more concerning for the development of therapeutic proteins?

The T-cell Dependent pathway is often of greater clinical concern. Because it involves affinity maturation and class switching to IgG, it can produce persistent, high-affinity ADAs that have a more significant and lasting impact on drug efficacy and safety [20] [23]. The TD pathway is responsible for the majority of IgG ADA responses to most therapeutics [23].

How can the risk of T-cell Dependent ADA formation be mitigated during drug design?

Several strategies focus on minimizing the activation of T-cells:

- Humanization: Replacing non-human sequences in therapeutic mAbs with human sequences to reduce foreign T-cell epitopes [20] [21].

- In Silico De-immunization: Using AI/ML tools to identify and remove potential T-cell epitopes from the protein sequence before clinical development [23].

- Tolerogenic Nanoparticles: Using nanoparticles designed to promote immune tolerance rather than activation [20] [4].

Can nanoparticle design influence which ADA pathway is activated?

Yes, the properties of nanocarriers like Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) can influence immunogenicity. For instance, the presence of polyethylene glycol (PEG) lipids on LNPs can trigger the formation of anti-PEG antibodies. This response is typically T-cell independent, leading to IgM antibodies that can cause accelerated blood clearance of subsequent doses [9]. Engineering PEG alternatives, such as zwitterionic poly(carboxybetaine) lipids, is a strategy to avoid this TI response [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Investigating ADA Pathways

Problem 1: Suspected T-cell Independent ADA Response

Observed Issue: Rapid clearance of a nanocarrier-based therapeutic upon repeated dosing, with assays detecting predominantly IgM-type ADAs.

Investigation Protocol:

- ADA Isotyping: Perform an ADA isotyping assay (e.g., a bridging ELISA or ECL-based assay) to confirm the dominant antibody isotype is IgM [23].

- Analyze Antigen Properties: Evaluate the therapeutic's structure. TI responses are often triggered by repetitive epitopes, such as those found on polymeric structures or certain nanoparticle surfaces, that can crosslink B-cell receptors [20] [23].

- In Vivo Confirmation: Administer the therapeutic to a T-cell deficient mouse model (e.g., nude mouse). The persistence of an IgM ADA response in the absence of functional T-cells confirms a TI pathway [20].

Problem 2: Confirming a T-cell Dependent ADA Response

Observed Issue: A patient develops high-affinity IgG ADAs against a humanized mAb after several weeks of treatment, leading to a loss of drug efficacy.

Investigation Protocol:

- Epitope Mapping: Use in silico tools (e.g., NetMHCIIpan) to predict T-cell epitopes within the therapeutic protein sequence. Peptides with strong binding affinity to MHCII are high-risk TCEs [22].

- In Vitro T-cell Assay:

- Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from naive human donors.

- Stimulate the cells with the full therapeutic protein or predicted TCE peptides.

- Measure T-cell activation by flow cytometry (e.g., CD4+ T-cell proliferation) or cytokine release (e.g., IL-2, IFN-γ) [22].

- Correlative Clinical Analysis: In clinical trials, monitor for the presence of drug-specific T-helper cells in circulation, which has been correlated with ADA formation [21].

Problem 3: High Aggregation Leading to Unwanted Immunogenicity

Observed Issue: A protein therapeutic with high aggregate content triggers a strong ADA response.

Investigation and Solution Protocol:

- Characterize Aggregates:

- Use Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) or Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to measure the size and concentration of sub-visible particles and aggregates [24]. NTA is particularly suited for polydisperse samples and provides a direct number-based concentration of particles.

- Dilute the sample in a suitable buffer to an ideal concentration of 10^7 to 10^9 particles/ml for NTA analysis [24].

- Optimize Formulation:

- Screen different buffers, pH levels, and excipients to improve stability.

- Use stabilizing agents to prevent aggregation and prolong shelf life [25].

- Re-assess Immunogenicity: Re-test the optimized, low-aggregate formulation in relevant in vitro or in vivo models to confirm reduced immunogenicity.

Comparative Analysis of ADA Formation Pathways

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the two primary ADA formation pathways.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ADA Formation Pathways

| Feature | T-cell Dependent Pathway | T-cell Independent Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| T-cell Help | Required (CD4+ T-cells) [23] | Not required [20] |

| Primary Antibody Isotype | IgG (and other class-switched antibodies) [20] [23] | IgM [20] [23] |

| Antibody Affinity | High (undergoes affinity maturation) [20] | Low (no affinity maturation) [20] |

| Immunological Memory | Yes (memory B cells) [20] | Limited or none [23] |

| Typical Antigen Trigger | Protein antigens with T-cell epitopes [20] | Repetitive, non-protein antigens (e.g., polysaccharides, some nanoparticles) [23] |

| Time to Response | Slower (days to weeks) | Rapid (hours to days) |

Visualizing the Immune Signaling Pathways

T-cell Dependent ADA Formation

T-cell Independent ADA Formation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Immunogenicity Risk Assessment

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., SM-86) | A key component of Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) for encapsulating and delivering nucleic acid therapeutics like mRNA [9]. | Used in Moderna's mRNA therapies (e.g., mRNA-3927) to form the core structure of the delivery vehicle [9]. |

| PEG Lipids (e.g., mPEG-DMG) | Confer a "stealth" effect on LNPs, reducing opsonization and prolonging circulation time. A common source of TI immunogenicity [9]. | A standard component in LNP formulations like BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines. Anti-PEG antibodies can lead to accelerated blood clearance [9]. |

| HO-PEG Lipids (e.g., OL-56) | A hydroxyl-terminated PEG lipid with lower immunogenicity potential, used to mitigate anti-PEG antibody responses [9]. | Employed in next-generation LNP formulations (e.g., Moderna's metabolic disorder therapies) to improve safety for repeated dosing [9]. |

| Poly(carboxybetaine) Lipids | A PEG alternative that provides stealth properties with lower immunogenicity and enhanced endosomal escape due to zwitterionic structure [9]. | Replacing PEG-lipids in novel LNPs to avoid anti-PEG immunity while maintaining delivery efficiency and enabling repeated administration [9]. |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, PEG) | Used in immunoassays and conjugation protocols to cover non-specific binding sites, preventing false-positive results [25]. | Added to buffers during ADA detection assays (e.g., bridging ELISA) or after nanoparticle-antibody conjugation to minimize non-specific signals [25]. |

| T-cell Epitope Prediction Software | In silico tools (AI/ML) to identify peptide sequences in a therapeutic protein that may bind to MHCII and activate T-cells [22] [23]. | Screening protein drug candidates during early development to de-immunize sequences by modifying high-risk T-cell epitopes [23]. |

| Stabilizing Buffers | Maintain the integrity and stability of nanoparticles and conjugated biomolecules during storage and experimentation [25]. | Used in conjugation kits to ensure optimal pH (e.g., pH 7-8 for gold nanoparticles) and prevent aggregation, which is a key factor in immunogenicity [25]. |

The Innovator's Toolkit: Methodologies for Engineering Low-Immunogenicity Nanoparticles

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges with PEG Alternatives

Question: Our PCB-LNPs show high transfection in cell lines but poor performance in vivo. What could be the cause?

This is often related to insufficient stealth properties, leading to rapid clearance by the immune system.

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate polymer hydration leading to protein adsorption and opsonization.

- Solution: Verify the molecular weight and grafting density of the PCB polymer. Research shows PCB with molecular weights of 2-4 kDa provides an optimal balance between stealth and endosomal escape. Ensure the PCB-lipid is incorporated at a molar ratio of 1.5-5% in the LNP formulation [26].

- Potential Cause 2: Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) due to anti-polymer antibodies.

- Solution: Perform an ABC assay with repeated dosing in mice. PCB-LNPs have been shown to mitigate the ABC phenomenon that is common with PEG-LNPs. If ABC is observed, consider adjusting the polymer structure or lipid anchor [26] [9].

- Experimental Protocol - ABC Phenomena Evaluation:

- Formulate your PCB-LNP encapsulating a reporter mRNA (e.g., firefly luciferase).

- Inject a primary dose (e.g., 0.5 mg/kg mRNA) intravenously into mice (n=5).

- On day 7, administer a secondary dose of the same formulation.

- Use an In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) to monitor luciferase expression at 4, 8, and 24 hours post-injection.

- Compare the signal intensity and duration after the first and second doses. A significant reduction in signal after the second dose indicates a potential ABC effect [26].

Question: How can I confirm that PCB-lipids enhance endosomal escape as proposed?

This requires a combination of direct and indirect assays.

- Solution 1: Perform a confocal microscopy assay with endosomal markers.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Treat cells (e.g., HeLa or THP-1) with LNPs encapsulating GFP-mRNA.

- Simultaneously stain endosomes/lysosomes with a LysoTracker or antibodies against early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) or lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1).

- At 2, 4, and 6 hours post-transfection, fix the cells and image using a confocal microscope.

- Co-localization analysis (e.g., Pearson's coefficient) will show the extent of LNP entrapment. A lower co-localization coefficient over time indicates more efficient escape [26].

- Solution 2: Utilize a destabilization assay with model membranes.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) mimicking the lipid composition of the endosomal membrane.

- Label the GUVs with a self-quenching fluorescent dye.

- Incubate with PCB-LNPs and PEG-LNPs at a pH of 7.4 and 5.5.

- Monitor fluorescence dequenching over time using a fluorometer. A rapid increase in fluorescence at low pH indicates membrane fusion or disruption, a proxy for endosomal escape. PCB-LNPs have demonstrated superior membrane fusion compared to PEG-LNPs at endosomal pH [26].

Formulation and Characterization Issues

Question: Our PCB-LNP formulations have low mRNA encapsulation efficiency. How can we improve this?

Low encapsulation is frequently a problem of formulation stability.

- Potential Cause: Improper lipid composition or mixing parameters during nano-precipitation.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Lipid Ratios: A standard LNP composition is 50% ionizable lipid, 10% phospholipid, 38.5-40% cholesterol, and 1.5-5% PCB-lipid. Systemically vary the percentage of ionizable lipid and cholesterol to find the optimal balance for your specific lipid components [26].

- Refine Mixing Technique: Use a microfluidic device for highly reproducible and rapid mixing. Ensure a 3:1 aqueous-to-ethanol flow rate ratio with a total flow rate of 12 mL/min for consistent particle formation [26] [27].

- Characterize Particle Properties: Use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to measure particle size and polydispersity index (PDI). Aim for a PDI below 0.2. Use a RiboGreen assay to precisely quantify encapsulated vs. free mRNA. All reported PCB-LNP formulations in the literature maintained encapsulation efficiency above 90% [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is there a push to replace PEG in LNPs, given its long history of safe use?

While PEG is effective as a stealth coating, two major drawbacks have emerged:

- Immunogenicity: The administration of PEGylated nanoparticles can induce anti-PEG antibodies. Upon repeated dosing, these antibodies cause the Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) phenomenon, reducing the therapeutic efficacy of subsequent doses [28] [29] [30].

- PEG Dilemma: The same steric barrier that provides stealth properties can also hinder cellular uptake and endosomal escape, creating a trade-off between circulation time and intracellular delivery efficiency [28] [9].

Q2: What are the key advantages of Zwitterionic PCB lipids over PEG lipids?

PCB lipids offer two primary advantages:

- Super-Hydrophilicity and Strong Hydration: PCB binds water molecules through electrostatic interactions, which is stronger than the hydrogen bonding utilized by PEG. This leads to superior stealth properties with extremely low protein adsorption [26] [31].

- Enhanced Endosomal Escape: Unlike inert PEG, the zwitterionic PCB can engage in electrostatic and dipole-dipole interactions with the endosomal membrane. This promotes membrane fusion and enhances the release of the therapeutic payload into the cytoplasm, leading to higher transfection efficiency [26] [9].

Q3: Are there other promising polymer alternatives to PEG?

Yes, the field is actively exploring several alternatives. Two prominent ones are:

- Brush-Shaped Polymer Lipids (BPLs): These are PEG-based but feature a brush-like architecture with multiple ethylene glycol side chains. This unique structure creates a dense steric barrier that reduces binding by anti-PEG antibodies, thereby mitigating the ABC effect while retaining the benefits of PEG [28] [9].

- Other Zwitterionic Polymers: Polymers like poly(sulfobetaine) are also being investigated for their non-fouling properties, though PCB is currently the most advanced in LNP applications [31].

Q4: How do I screen a library of novel polymer-lipids for LNP formulation?

A standard screening workflow involves:

- Synthesis: Create a library of polymer-lipids with systematic variations in polymer molecular weight, structure, and lipid tail length [28] [26].

- In Vitro Screening:

- Formulate LNPs with each candidate and encapsulate a reporter mRNA (e.g., firefly luciferase or GFP).

- Transfect immortalized (e.g., HeLa) and primary cells (e.g., human T-cells).

- Measure transfection efficiency (e.g., luciferase activity) and cell viability. Select top performers for further testing [28] [26].

- In Vivo Validation:

The table below summarizes key performance metrics of PCB-LNPs compared to standard PEG-LNPs, as reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PCB-LNPs vs. PEG-LNPs

| Parameter | PEG-LNPs (DMG-PEG2000) | PCB-LNPs (M2 Formulation) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA Transfection Efficiency | Baseline | 2 to 5-fold higher | Across multiple cell lines (HeLa, THP-1, Jurkat) and primary human T-cells [26] |

| Anti-PEG Antibody Binding | High | Minimal to undetectable | In vitro assay with anti-PEG antibodies [28] [26] |

| Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) | Significant reduction after 2nd dose | Maintained efficiency after repeated dosing | Mouse model, repeated systemic administration [26] |

| Endosomal Escape | Standard | Enhanced | Mechanistic assays (e.g., Cryo-EM, model membrane fusion) [26] [9] |

| CAR Expression in T-Cells | ~45% CAR+ cells | >95% CAR+ cells | Jurkat T-cells transfected with anti-CD19 CAR mRNA [26] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCB-LNP Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Cationic Lipid | Encapsulates mRNA via electrostatic interaction; critical for endosomal escape. | SM-102, ALC-0315, MC3, CKKE12 [26] [9] |

| Phospholipid | Structural component of the LNP bilayer. | DSPC (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) [26] |

| Cholesterol | Stabilizes the LNP structure and enhances membrane fluidity. | Plant-derived cholesterol is often used [9] |

| PCB-Lipid | Provides stealth properties and enhances endosomal escape; replaces PEG-lipid. | Synthesized via RAFT polymerization; e.g., DMG-PCB2k (M2) [26] |

| Brush Polymer Lipid (BPL) | Alternative to PEG; reduces anti-polymer antibody binding. | Synthesized via ATRP; brush-shaped poly(PEGMA) [28] |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the key mechanistic pathway through which PCB-LNPs enhance mRNA delivery compared to PEG-LNPs.

Diagram 1: PCB-LNP Mechanism of Action

The logical workflow for developing and evaluating novel PEG alternatives like PCB-lipids is shown below.

Diagram 2: Polymer-Lipid Evaluation Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Immunogenicity in Nanoparticle Design

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when developing stealth nanoparticles, providing targeted solutions based on current nanotechnology advances.

Q1: How can I overcome the "PEG dilemma" where PEGylation improves circulation but reduces cellular uptake?

Challenge: Traditional PEG coatings create a steric barrier that limits cellular uptake and endosomal escape, reducing therapeutic efficacy [32] [9].

Solutions:

- Implement stimuli-responsive PEG shedding: Design PEG linkages that cleave in response to tumor microenvironment triggers like acidic pH or specific enzymes (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases). This preserves circulation stability while restoring cellular interaction at the target site [32].

- Optimize PEG architecture: Use branched or Y-shaped PEG polymers rather than linear chains. These create denser surface layers with reduced immunogenicity and can help mitigate anti-PEG antibody formation [9].

- Modulate PEG density and chain length: Systematically test PEG molecular weights and surface coverage to find the optimal balance between stealth properties and cellular uptake [32].

Experimental Protocol: pH-responsive PEG Shedding Evaluation

- Synthesize nanoparticles with PEG linked via pH-sensitive bonds (e.g., hydrazone or acetal linkages).

- Characterize particle size, zeta potential, and PEG density before and after incubation at pH 7.4 and 6.5.

- Evaluate protein corona formation in serum-containing media via SDS-PAGE or LC-MS.

- Assess cellular uptake in relevant cell lines using flow cytometry and confocal microscopy.

- Compare endosomal escape efficiency using fluorescent dye release assays.

Q2: What strategies can reduce anti-PEG antibody formation and Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC)?

Challenge: Repeated administration of PEGylated nanoparticles can trigger anti-PEG antibodies, leading to accelerated clearance and potential hypersensitivity reactions [9] [7].

Solutions:

- Replace PEG with alternative polymers: Implement zwitterionic coatings like poly(carboxybetaine) (PCB), which demonstrate superior anti-fouling properties with reduced immunogenicity [9].

- Utilize brush-shaped polymer-lipid (BPL) conjugates: These adopt a "mushroom regime" conformation that creates effective steric barriers while reducing anti-PEG antibody binding [9].

- Employ hydroxyl-terminated PEG (HO-PEG) lipids: Moderna's clinical formulations have validated that HO-PEG lipids exhibit lower immunogenicity compared to methoxy-terminated PEG [9].

- Implement PEG competition strategies: Co-administer high molecular weight PEG (≥30 kDa) to transiently occupy B-cell receptors and block anti-PEG antibody binding [9].

Q3: How do ionizable lipids in LNPs contribute to immunogenicity, and how can this be mitigated?

Challenge: Ionizable lipids, while essential for mRNA encapsulation and delivery, can activate innate immune responses through Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling, leading to NF-κB and IRF activation and inflammatory cytokine production [33].

Solutions:

- Develop charge-switchable lipids: Design lipids that are neutral at physiological pH (7.4) but become positively charged in acidic endosomal environments (pH 4.0-6.5). This reduces nonspecific immune activation while maintaining endosomal escape capability [34].

- Screen ionizable lipid libraries: Systematically evaluate different lipid structures for reduced TLR4 activation while maintaining transfection efficiency.

- Formulate with immunosuppressive components: Incorporate lipids that specifically inhibit immune signaling pathways without compromising delivery efficiency.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing LNP Immunogenicity

- Prepare LNPs with varying ionizable lipid structures while keeping other components constant.

- Stimulate THP-1 monocyte cells with empty LNPs (lacking mRNA payload).

- Measure NF-κB and IRF activation using reporter assays at 24, 48, and 72 hours.

- Quantify cytokine production (IL-1, IL-6, TNFα, IFNs) via ELISA or multiplex assays.

- Compare results to positive controls (TLR agonists) and negative controls (ionizable lipid-deficient LNPs).

Q4: How does protein corona formation undermine active targeting strategies, and how can this be prevented?

Challenge: Serum proteins adsorb onto nanoparticle surfaces, forming a protein corona that masks targeting ligands and redirects nanoparticles to off-target tissues [32].

Solutions:

- Engineer ultra-low fouling surfaces: Utilize zwitterionic polymers or dense PEG brushes that minimize protein adsorption through strong hydration layers [32] [9].

- Implement topographic control: Create surface nanostructures that physically repel protein adsorption.

- Quantify protein binding affinity: Use surface plasmon resonance or isothermal titration calorimetry to measure equilibrium binding constants (KA) of proteins to nanoparticles. Select formulations with lower KA values for improved circulation [32].

Comparative Analysis of Stealth Coating Strategies

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Nanoparticle Surface Modification Strategies

| Strategy | Circulation Half-life | Cellular Uptake | Immunogenicity | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear PEG | High (initial doses) | Reduced | Moderate (ABC effect) | Well-established chemistry, proven clinical success [32] [9] |

| Branched PEG | High | Moderate | Low-Moderate | Reduced antibody recognition, denser surface coverage [9] |

| Zwitterionic PCB | High | High | Low | Excellent anti-fouling, enhances endosomal escape [9] |

| Brush Polymers (BPL) | High | Moderate-High | Low | Reduced anti-PEG antibody binding, tunable properties [9] |

| Stimuli-responsive PEG | Variable (context-dependent) | High at target site | Moderate | Balances circulation and uptake, targeted activation [32] |

Table 2: Immune Activation Profiles of Different LNP Components

| Component | Immune Receptor Engagement | Primary Signaling Pathways | Resultant Immune Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | TLR4 [33] | NF-κB, IRF [33] | Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNFα), type I interferons [7] [33] |

| PEG Lipids | Anti-PEG B-cell receptors [9] [7] | Complement activation [7] | Anti-PEG antibodies, ABC phenomenon, hypersensitivity [9] [7] |

| Cationic Lipids | NLRP3 inflammasome [7] | Caspase-1 activation [7] | IL-1β, IL-18, pyroptosis [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Advanced Nanoparticle Surface Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Commercial Sources/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Polymers | Poly(carboxybetaine) (PCB) lipids | PEG replacement with enhanced endosomal escape and reduced immunogenicity [9] | Custom synthesis per Luozhong et al. [9] |

| Structural PEG Variants | Branched PEG, Y-shaped PEG, Brush Polymer Lipids (BPL) | Reduced immunogenicity while maintaining stealth properties [9] | Biopharma PEG [9] |

| Ionizable Lipids | SM-102, ALC-0315, switchable lipids | mRNA encapsulation, endosomal escape; target of immune recognition [9] [33] | Commercial LNP formulations [33] |

| PEG Lipids | mPEG-DMG, mPEG-DSPE, HO-PEG lipids | Stealth properties, circulation longevity; source of immunogenicity [9] | Biopharma PEG (GMP & non-GMP) [9] |

| Characterization Tools | NF-κB/IRF reporter cell lines, TLR knockout cells | Mechanism of immune activation studies [33] | Commercial cell lines (THP-1 derivatives) [33] |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can we completely eliminate nanoparticle immunogenicity, or is some level inevitable? While complete elimination remains challenging, recent advances like switchable nanoparticles (SNPs) demonstrate orders-of-magnitude reduction in immunogenicity while maintaining delivery efficiency. The goal is to minimize immunogenicity to levels that don't compromise safety or efficacy, particularly for therapies requiring repeated administration [34].

Q: How significant is the contribution of the LNP itself versus the mRNA payload to overall immunogenicity? Studies with empty LNPs (lacking mRNA) reveal that the ionizable lipid component alone can activate immune responses similar in magnitude to complete mRNA-LNPs, suggesting the LNP itself contributes significantly to innate immune activation [33].

Q: What are the most promising PEG alternatives currently in development? Poly(carboxybetaine) (PCB) lipids and brush-shaped polymer-lipid (BPL) conjugates show exceptional promise. PCB offers enhanced endosomal escape with reduced immunogenicity, while BPLs maintain stealth properties with minimal anti-PEG antibody binding [9].

Q: How does the route of administration affect nanoparticle immunogenicity? Intravenous injection presents higher immunogenicity risk, particularly at low doses. Intramuscular injection creates a drug depot effect that can be more suitable for repeated dosing regimens [9].

Q: What critical quality attributes should be monitored when developing stealth nanoparticles? Beyond standard physicochemical characterization (size, PDI, zeta potential), specifically monitor protein corona composition, anti-PEG antibody levels after repeated administration, complement activation, and cytokine release profiles [32] [9] [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Suboptimal Immune Responses

Problem: Inadequate focusing of immune responses toward target epitopes.

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Steric Occlusion of Epitopes [35] | Low titers of target antibodies despite high overall immunogenicity; high off-target response. | Optimize antigen spacing and density on the nanoparticle scaffold [35]. |

| Low Naïve B Cell Precursor Frequency [35] | Poor B cell recruitment and germinal center establishment for the target epitope. | Use epitope scaffolding to present the target in isolation and increase precursor engagement [35]. |

| Immunodominance of Scaffold [35] | High antibody titers against the nanoparticle platform itself, rather than the antigen. | Employ "resurfacing" strategies, such as hyperglycosylation, to mask scaffold epitopes [35]. |

| Incorrect Epitope Conformation [36] | Elicited antibodies do not bind the native pathogen antigen or lack neutralizing activity. | Utilize computational design (e.g., Rosetta) for precise epitope grafting that preserves native structure [36]. |

Troubleshooting Nanoparticle Assembly and Antigen Incorporation

Problem: Low yield or instability of antigen-displaying nanoparticles.

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Disruption of Nanoparticle Self-Assembly [35] | Incomplete particle formation, high polydispersity, or protein aggregation. | Employ enzymatic conjugation (e.g., Sortase) or SpyTag/SpyCatcher for controlled, site-specific antigen attachment [35]. |

| Cross-linking of Critical Epitope Residues [37] | Antigen-specific immune response is abolished, despite successful nanoparticle formation. | Modify antigens by adding terminal residues (outside the epitope) to provide "handles" for cross-linking [37]. |

| Choice of Cross-linking Chemistry [37] | Altered immune response profiles (e.g., Th1 vs. Th2) depending on the cross-linker used. | Systematically evaluate different cross-linking chemistries (e.g., reducible vs. non-reducible) for desired immune outcomes [37]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using protein nanoparticles like I53-50 and mi3 for antigen display?

These platforms enable multivalent antigen display, which significantly magnifies the overall humoral immune response by enhancing B cell receptor crosslinking [35]. Their symmetrical, ordered structures (e.g., tetrahedral, octahedral, icosahedral) allow for stoichiometrically precise presentation of multiple antigens, which can be engineered to favor the engagement of B cells targeting conserved, subdominant epitopes [35]. This rational display helps shift immunodominance hierarchies toward the elicitation of broadly neutralizing antibodies [35].

Q2: How can I reduce the inherent immunogenicity of the nanoparticle scaffold itself?

A key strategy is to mask or "resurface" the scaffold's epitopes. This can be achieved by engineering the scaffold surface to incorporate glycan shields that sterically block antibody recognition [35]. The choice of a small, minimally immunogenic scaffold and the use of computational design to select human-derived or highly stable protein sequences can also lower the risk of eliciting off-target antibody responses [36] [35].

Q3: My antigen of interest is a small peptide. How can I incorporate it into a nanoparticle without affecting its immunogenicity?

For small peptides, a Peptide Nanocluster (PNC) approach can be effective [37]. This involves adding non-epitope terminal residues (e.g., GKCSIINFEKLCKG) to the core peptide to provide functional groups for cross-linking without engaging critical epitope residues [37]. The PNC is then formed by desolvation and stabilized using cross-linkers that target these added residues, preserving the native epitope structure for correct immune recognition [37].

Q4: What computational tools are available for the design of epitope-scaffold immunogens?

A typical workflow combines several tools [36]:

- Scaffold Identification: Use structural alignment algorithms like MAMMOTH and TM-align to find protein scaffolds that can structurally accommodate your epitope of interest [36].

- Epitope Grafting & Optimization: Tools like RosettaDesign are used for "side-chain grafting" and "flexible-backbone remodeling" to optimally fit the epitope onto the selected scaffold while maintaining its structure [36].

- Model Quality Assessment: Use scoring functions to select the best-designed models from a pool of candidates for further experimental testing [36].

Q5: How can I experimentally map which epitopes on my nanoparticle vaccine are immunodominant?

Advanced high-throughput screening technologies like LIBRA-seq (Linking B-cell Receptor to Antigen Specificity through sequencing) can be employed [38]. This method allows you to simultaneously map the antigen specificity of a vast number of B cell receptors by exposing B cells to a library of antigen-labeled lentiviruses and then sequencing the paired BCR and antigen barcode [38].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Conjugation of Antigens to Nanoparticles Using SpyTag/SpyCatcher

This protocol describes a modular "plug-and-display" method for attaching antigens to nanoparticle scaffolds, a strategy highlighted for its utility in creating precisely assembled vaccines [35].

Principle: The SpyTag peptide (13 amino acids) spontaneously forms a covalent isopeptide bond with the SpyCatcher protein when mixed. By genetically fusing SpyTag to your antigen and SpyCatcher to the nanoparticle (e.g., I53-50), you can achieve site-specific, stable conjugation [35].

Materials:

- Purified nanoparticle-SpyCatcher fusion protein

- Purified antigen-SpyTag fusion protein

- Reaction Buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4)

- Equipment: SDS-PAGE gel, chromatography system (e.g., FPLC) for purification

Procedure:

- Mixing: Combine the nanoparticle-SpyCatcher and antigen-SpyTag at the desired molar ratio in reaction buffer. A typical reaction may use a slight molar excess of antigen to drive conjugation to completion.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at room temperature or 4°C for several hours (e.g., 2-16 hours) to allow for complete covalent bonding.

- Purification: Separate the conjugated product from unreacted antigen and nanoparticle using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) or density gradient centrifugation.

- Validation: Analyze the final product via SDS-PAGE (to confirm covalent coupling) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) to verify particle size and monodispersity.

Protocol: Synthesis of Peptide Nanoclusters (PNC)

This protocol details the formation of biomaterials composed almost entirely of antigen, minimizing off-target immune responses [37].

Principle: Peptides are desolvated in an organic solvent, leading to the formation of nanoscale clusters. These clusters are then stabilized through cross-linking of functional groups on the peptide chains [37].

Materials:

- Peptide Antigen: Modified with terminal cross-linking handles (e.g., SLS: GKCSIINFEKLCKG).

- Cross-linker: e.g., Tris(2-maleimidoethyl)amine (for thiol-maleimide chemistry).

- Solvents: Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), Diethyl Ether (DEE).

- Equipment: Syringe pump, centrifuge, sonicator, dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument.

Procedure:

- Solubilization: Dissolve the modified peptide in HFIP at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL [37].

- Cross-linker Addition: Add the desired amount of cross-linker to the peptide solution under constant stirring (400 rpm) [37].

- Desolvation: Using a syringe pump, add DEE to the stirring solution at a controlled rate (e.g., 1 mL/min). This induces peptide clustering [37].

- Reaction: Allow the solution to mix for a specified time to enable cross-linking stabilization [37].

- Isolation: Centrifuge the solution at 18,000 g for 7 minutes. Remove the supernatant [37].

- Resuspension: Resuspend the pellet (the PNC) in water or buffer. Use brief probe sonication to ensure a homogeneous suspension [37].

- Characterization: Determine the size and polydispersity (PDI) of the PNC using DLS [37].

Rational Antigen Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| SpyTag/SpyCatcher System [35] | A modular protein ligation tool for covalent, site-specific conjugation of antigens to nanoparticle scaffolds, enabling a "plug-and-display" assembly. |

| Ferritin & I53-50 Nanoparticles [35] | Protein-based self-assembling nanoparticles used as scaffolds for the multivalent, geometric display of antigens (e.g., trimeric viral glycoproteins). |

| Rosetta Software Suite [36] | A comprehensive computational modeling software used for protein structure prediction, epitope scaffolding, side-chain remodeling, and optimizing protein-protein interactions. |

| Peptide Nanoclusters (PNC) [37] | A biomaterial formed entirely from cross-linked peptide antigens, designed to maximize delivery of the target epitope and minimize off-target immunity. |

| LIBRA-seq [38] | A high-throughput screening technology that links B-cell receptor (BCR) sequences to antigen specificity by using a library of DNA-barcoded antigens, allowing for rapid mapping of immunodominant epitopes. |

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as the leading delivery system for RNA therapeutics, a success largely catalyzed by the global deployment of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines [39]. At the heart of LNP performance is the ionizable lipid, a pH-sensitive component critical for mRNA encapsulation, cellular delivery, and endosomal escape [39] [40]. While first-generation ionizable lipids like SM-102 and ALC-0315 proved effective, they are associated with significant challenges, including inflammatory side effects and suboptimal potency [33] [40].

This technical resource, framed within the context of strategies for reducing nanoparticle immunogenicity, provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers developing next-generation LNPs. The focus is on novel ionizable lipids engineered to enhance efficacy and improve safety profiles by mitigating unwanted immune activation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common LNP Challenges

This section addresses specific, high-priority issues encountered during LNP research and development, offering solutions grounded in recent advances in ionizable lipid design.

FAQ 1: How can I reduce the inflammatory response triggered by my LNP formulation?

- Problem: My LNP formulation, even without mRNA, causes significant innate immune activation, leading to high cytokine production (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) in vitro and elevated reactogenicity in vivo. This inflammatory profile is undesirable for many therapeutic applications, such as protein replacement therapies [41] [40].

- Background: Conventional ionizable lipids can activate the innate immune system, predominantly through Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4), leading to the activation of transcription factors NF-κB and IRF [33]. This pathway is a major contributor to LNP-induced inflammation.

- Solution & Experimental Evidence:

- Utilize Anti-inflammatory Ionizable Lipids: A novel strategy involves designing ionizable lipids that incorporate anti-inflammatory moieties. For example, researchers have created a class of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)-functionalized lipids (HLs). HCQ is known to inhibit endosomal TLRs (TLR3, TLR7, TLR9) and the cGAS-STING signaling pathway [41].

- Validation Protocol: To test the efficacy of such lipids, you can:

- Transfert immune cells (e.g., THP-1 monocyte cell line or human monocyte-derived dendritic cells) with LNPs encapsulating a non-immunogenic reporter mRNA (e.g., firefly luciferase).

- Measure cytokine secretion 24 hours post-transfection using a multiplex ELISA or Luminex assay. Key cytokines to analyze include IL-6, IL-1β, and IFN-γ.

- Compare the inflammatory profile of the novel HL LNPs against benchmark LNPs (e.g., formulated with SM-102). Studies have shown that HL LNPs can significantly suppress the production of these proinflammatory cytokines compared to controls [41].

FAQ 2: My LNP formulation shows low transfection potency and protein expression. How can I improve delivery efficiency?

- Problem: The LNP formulation demonstrates poor mRNA delivery, resulting in low protein expression in target cells, both in vitro and in vivo.

- Background: The delivery efficiency of an ionizable lipid is influenced by its chemical structure, including the headgroup, linker, and tail, which affect pKa, membrane fusion, and endosomal escape [39] [40].

- Solution & Experimental Evidence:

- Employ Lipids with Enhanced mRNA Interaction: Novel ionizable lipids are being designed with structures that promote stronger interactions with the mRNA payload. For instance, the lipid FS01 features a squaramide headgroup and an aromatic tail. Molecular dynamics simulations confirm that this structure enhances mRNA stability through π-π stacking interactions with nucleobases and hydrogen bonding via the headgroup [42] [40].

- Adopt AI-Designed Lipids: Artificial intelligence (AI) models can now predict the apparent pKa and mRNA delivery efficiency of ionizable lipids, accelerating the rational design of high-potency candidates [43].

- Validation Protocol: To assess improved potency:

- Formulate LNPs with the novel lipid (e.g., FS01, ARV-T1, or an AI-designed lipid) and a model mRNA (e.g., encoding SARS-CoV-2 spike protein or a luciferase reporter).

- Perform an in vivo potency study in a relevant animal model (e.g., BALB/c mice). Administer the LNP formulation intramuscularly.

- Measure output: For a vaccine, quantify antigen-specific binding antibodies and virus-neutralizing antibodies in serum 2-3 weeks post-immunization using an ELISA-based assay. Lipids like ARV-T1 have been shown to induce over 10-fold higher neutralizing antibody titers compared to SM-102 LNPs [39]. For a reporter, measure luminescence in target tissues.

FAQ 3: My LNPs are unstable and exhibit high polydispersity. How can I optimize the formulation process?

- Problem: The manufactured LNPs have a broad size distribution (high PDI), are unstable, and tend to aggregate, which compromises reproducibility and efficacy.

- Background: Particle size, polydispersity, and stability are critical quality attributes influenced by lipid composition, formulation methods, and process parameters [44] [45].

- Solution & Experimental Evidence:

- Optimize Lipid Composition and Manufacturing: The inclusion of structurally optimized ionizable lipids can inherently improve LNP characteristics. For example, LNPs formulated with ARV-T1 demonstrated smaller particle sizes and lower polydispersity indices compared to SM-102 LNPs [39].

- Implement Robust Characterization: Rigorous in-process quality control is essential.

- Validation Protocol:

- Manufacture LNPs using a controlled method like microfluidics to ensure reproducible mixing.

- Characterize the LNPs using the following techniques:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): For measuring hydrodynamic diameter and PDI.

- Multi-Angle Dynamic Light Scattering (MADLS) or Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): For a more detailed size distribution and concentration analysis, especially for polydisperse samples [45].

- Zeta Potential Measurement: To assess surface charge, which relates to colloidal stability. Use a diluted PBS buffer to improve measurement visibility [45].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Novel vs. Benchmark Ionizable Lipids

| Ionizable Lipid | Key Structural Feature | Reported pKa | In Vivo Potency (vs. Benchmark) | Key Safety & Immunogenicity Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARV-T1 [39] | Cholesterol-tailed, ester linkage | 6.73 | >10x higher neutralizing Ab vs. SM-102 | Ester linkage enables rapid metabolism; improved safety profile |

| FS01 [42] [40] | Squaramide head, aromatic tail | N/A | Superior to SM-102, ALC-0315, MC3 | Well-balanced immune activation; minimal inflammation & liver toxicity |

| HCQ-Lipids (HL) [41] | Hydroxychloroquine-functionalized | N/A | Retained expression capacity | Significantly suppressed proinflammatory cytokine production |

| AI-Designed Lipids [43] | AI-optimized structures | ~6.0-7.0 | Comparable or superior to MC3/SM-102 | Designed for desired pKa, which can influence reactogenicity |

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization Assays

Protocol 1: Assessing Innate Immune Activation via NF-κB/IRF Reporter Assays

This protocol is critical for evaluating the intrinsic immunogenicity of novel ionizable lipids, as outlined in FAQ 1.

- Cell Line: Use THP-1 monocyte cells stably transfected with secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter for NF-κB and a luciferase reporter for IRF activation [33].

- Stimulation: Stimulate cells with empty LNPs (lacking mRNA) to isolate the effect of the lipid component. Include controls: R848 (TLR7/8 agonist) and MPLA (TLR4 agonist).

- Measurement:

- Collect supernatant at 24, 48, 72, and 120 hours post-stimulation.

- NF-κB activation: Quantify SEAP activity in the supernatant using a colorimetric assay.

- IRF activation: Perform a luciferase assay on cell lysates.

- Interpretation: As demonstrated in research, empty ionizable LNPs (e.g., LNP-ALC0315, LNP-SM102) can induce a time-dependent increase in NF-κB and IRF activation, peaking at 48-72 hours. A significant reduction in this signal with a novel lipid indicates a less immunogenic profile [33].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Potency and Immunogenicity Evaluation

This protocol validates the solutions proposed in FAQ 2 and generates data comparable to Table 1.

- LNP Formulation: Prepare LNPs containing the novel ionizable lipid and an mRNA encoding a target antigen (e.g., Varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein).

- Animal Immunization: Administer the LNP formulation to groups of mice (e.g., C57BL/6 or BALB/c) via the intramuscular route. Include a control group immunized with benchmark LNPs (e.g., SM-102 LNP).

- Sample Collection: Collect serum samples pre-immunization and at 2- or 3-week intervals post-immunization.

- Analysis:

- Humoral Response: Measure antigen-specific antibody titers (e.g., total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a) using ELISA.

- Neutralizing Antibodies: Perform a virus neutralization assay if applicable.

- Cellular Response: Isolate splenocytes and measure antigen-specific T cell responses (e.g., IFN-γ ELISpot) or memory B cell formation by flow cytometry [42] [40].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

TLR4-Mediated LNP Immunogenicity

The diagram below illustrates the mechanism by which ionizable lipids in LNPs can trigger an innate immune response, a key consideration for troubleshooting reactogenicity.

Rational Ionizable Lipid Design Workflow

This flowchart outlines the modern, integrated approach to designing novel ionizable lipids, combining AI-driven design with experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for LNP Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in LNP Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | Core functional component for mRNA encapsulation and endosomal escape. | SM-102, ALC-0315 (benchmarks); ARV-T1 [39], FS01 [40], HCQ-lipids [41] (novel lipids). |

| Helper Phospholipid | Structural component that stabilizes the LNP bilayer. | DSPC (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) [39] [33]. |

| Cholesterol | Enhances LNP stability and integrity by filling gaps between lipids. | Plant-derived cholesterol [39]. |

| PEGylated Lipid | Controls particle size during formation, reduces aggregation, and modulates pharmacokinetics. | DMG-PEG2000 [39] or ALC-0159 [33]. |

| Microfluidic Device | Enables reproducible, scalable mixing of lipid and aqueous phases to form monodisperse LNPs. | Used in controlled manufacturing processes [44]. |

| THP-1 Reporter Cell Line | In vitro model for screening LNP-induced innate immune activation via NF-κB and IRF pathways [33]. | Cells engineered with SEAP (NF-κB) and luciferase (IRF) reporters. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Critical analytical tool for measuring LNP hydrodynamic size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential [45]. | Used for routine quality control of formulations. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs