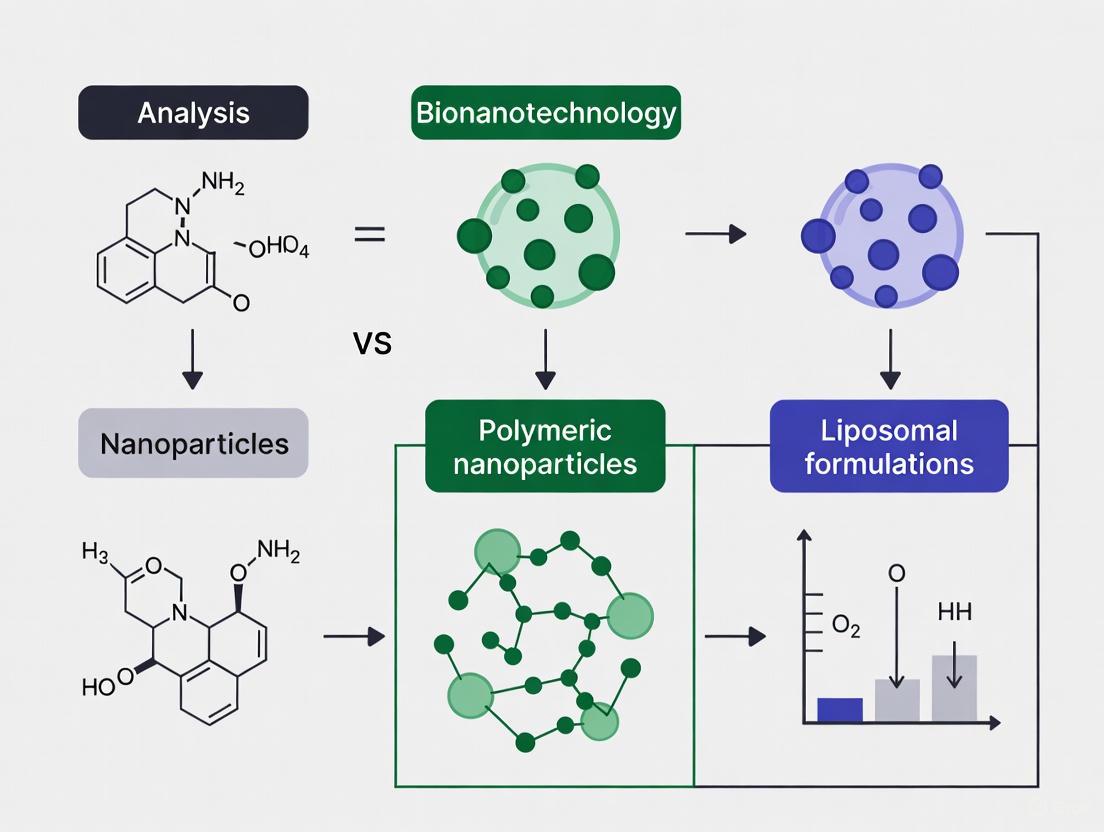

Polymeric Nanoparticles vs. Liposomal Formulations: A Comprehensive Analysis for Advanced Drug Delivery

This article provides a systematic comparison of polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) and liposomal formulations, two cornerstone technologies in modern nanomedicine.

Polymeric Nanoparticles vs. Liposomal Formulations: A Comprehensive Analysis for Advanced Drug Delivery

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) and liposomal formulations, two cornerstone technologies in modern nanomedicine. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental structures, synthesis methods, and material sciences underpinning each system. The analysis delves into their respective applications in overcoming biological barriers, such as the blood-brain barrier and tumor microenvironment, and details advanced engineering strategies for enhancing targeting, circulation time, and controlled release. A critical evaluation of scalability, stability, and regulatory challenges is presented, alongside a comparative assessment of their clinical translation, therapeutic efficacy, and performance in specific disease contexts. This review synthesizes key decision-making criteria for selecting the optimal nanocarrier and discusses future trajectories, including hybrid systems and personalized medicine approaches.

Deconstructing the Architectures: Core Structures and Material Sciences of PNPs and Liposomes

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) represent a cornerstone of modern nanomedicine, offering innovative solutions to complex drug delivery challenges. These nanoscale carriers, typically ranging from 10 to 1000 nanometers, are engineered to transport therapeutic agents to specific sites in the body, thereby enhancing drug efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects [1]. Their nanoscale dimensions facilitate cellular uptake and allow these particles to cross biological barriers, including the challenging blood-brain barrier [1]. A major advantage of PNPs is their chemical versatility, enabling the creation of a virtually limitless range of polymers with tailored properties through various polymerization methods and functional groups [1].

Biodegradability is a critical characteristic of modern polymeric nanoparticles, distinguishing them from earlier non-degradable materials. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles (BPNPs) are designed to break down into non-toxic byproducts that are safely eliminated from the body, minimizing long-term accumulation and toxicity concerns [2]. This review focuses on two of the most prominent biodegradable polymers in pharmaceutical applications: poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), a synthetic polymer, and chitosan, a natural polysaccharide. Through a comprehensive comparison of their properties, applications, and performance data, this guide provides researchers with evidence-based insights for selecting appropriate polymer systems for specific drug delivery challenges within the broader context of nanoparticle development, particularly in comparison to liposomal formulations.

Composition and Structure of Polymeric Nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles are classified based on their structural organization into two primary categories: nanospheres and nanocapsules. Nanospheres are matrix-like systems where the drug is uniformly dispersed throughout the polymer matrix, while nanocapsules exhibit a reservoir system with a drug-filled core surrounded by a polymeric shell [2]. This structural distinction significantly influences drug loading capacity, release kinetics, and protection of the encapsulated therapeutic agent.

The composition of PNPs can be derived from either natural or synthetic sources. Natural polymers include polysaccharides such as chitosan, alginate, and cellulose, as well as polypeptides like gelatin, collagen, and albumin [2]. These materials are characterized by excellent biocompatibility and often inherent bioactivity. Synthetic polymers, particularly PLGA and other polyesters like polylactic acid (PLA) and poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL), offer precisely controlled properties including degradation rates, mechanical strength, and drug release profiles [2]. The selection between natural and synthetic polymers depends on the specific application requirements, with increasing research focused on hybrid systems that combine the advantages of both categories.

Table 1: Classification of Biodegradable Polymers for Nanoparticle Formulation

| Polymer Type | Examples | Sources | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Chitosan [2] | Crustacean shells [3] | Mucoadhesive, biocompatible, antimicrobial |

| Alginate [2] | Brown algae | pH-responsive gelling, biocompatible | |

| Gelatin [2] | Animal collagen | Low immunogenicity, tunable isoelectric point | |

| Albumin [2] | Human blood, plants | Low immune reactivity, high binding capacity | |

| Synthetic Polymers | PLGA [4] [2] | Lactide and glycolide monomers | Tunable degradation, controlled release, FDA-approved |

| PLA [2] | Lactic acid monomers | Slower degradation than PLGA, high mechanical strength | |

| PCL [2] | ε-Caprolactone monomers | Slow degradation, suitable for long-term delivery |

Key Characteristics of Polymeric Nanoparticles

Biodegradability and Biocompatibility

Biodegradability is a fundamental requirement for polymeric nanoparticles intended for therapeutic use. PLGA undergoes hydrolysis in the body, breaking down into its monomeric constituents—lactic acid and glycolic acid—which enter the Krebs cycle and are metabolized into water and carbon dioxide [2]. This degradation rate can be precisely tuned by varying the lactide to glycolide ratio and molecular weight, with 50:50 ratios typically degrading fastest [4]. Chitosan, in contrast, is primarily degraded by lysozymes through enzymatic hydrolysis of its glycosidic linkages, producing non-toxic oligosaccharides that are incorporated into metabolic pathways [2]. Both polymers have demonstrated excellent safety profiles, with PLGA having multiple FDA-approved products and chitosan classified as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) by the FDA [3].

Drug Loading and Release Kinetics

The drug encapsulation efficiency and release profiles of PNPs are influenced by multiple factors including polymer composition, drug-polymer interactions, and nanoparticle structure. PLGA nanoparticles exhibit high drug encapsulation efficiency, particularly for hydrophobic compounds, protecting encapsulated drugs from degradation and enhancing stability [2]. The controlled release capability of PLGA is one of its most valued attributes, with release profiles that can extend from days to several months depending on formulation parameters [4]. Chitosan nanoparticles demonstrate particularly high efficiency for encapsulating macromolecules like proteins and peptides, with their release kinetics influenced by the polymer's mucoadhesive properties and swelling behavior in different physiological environments [2].

Comparative Analysis of PLGA and Chitosan Nanoparticles

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of PLGA and Chitosan Nanoparticles

| Parameter | PLGA Nanoparticles | Chitosan Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Origin | Synthetic copolymer [4] | Natural polysaccharide from chitin [3] |

| Biodegradation | Hydrolysis into lactic/glycolic acids [2] | Enzymatic degradation by lysozymes [2] |

| Biocompatibility | Excellent; FDA-approved for multiple products [4] | Excellent; GRAS status by FDA [3] |

| Drug Release Profile | Sustained release (weeks to months) [4] | Variable release (hours to days) [2] |

| Mucoadhesiveness | Low without modification [2] | High; adheres to mucosal surfaces [2] |

| Antimicrobial Activity | Not inherent | Inherent antimicrobial properties [2] |

| Typical Size Range | 50-300 nm [5] | 80-400 nm [2] |

| Loading Efficiency | High for hydrophobic drugs [2] | High for macromolecules [2] |

| Scale-up Feasibility | Well-established for scaling [2] | Challenges in large-scale production [6] |

| Cost Considerations | Moderate to high | Low to moderate [3] |

The comparative analysis reveals distinct advantage profiles for each polymer. PLGA's synthetic nature provides precisely controllable degradation and release kinetics, making it particularly suitable for long-acting injectable formulations where predictable sustained release over weeks or months is required [4]. Its versatility is evidenced by commercial products like Lupron Depot for hormone therapy and Zilretta for osteoarthritis pain [4]. Chitosan's natural origin confers inherent bioactivity including mucoadhesion and antimicrobial properties, making it ideal for mucosal delivery systems and applications where infection control is beneficial [3]. The cationic nature of chitosan enables strong electrostatic interactions with negatively charged mucosal surfaces and biological membranes, enhancing residence time and absorption at these sites [2].

Experimental Data and Methodologies

Formulation Protocols

PLGA Nanoparticle Preparation via Emulsion-Solvent Evaporation The emulsion-solvent evaporation method is widely employed for PLGA nanoparticle synthesis. The standard protocol involves: (1) Dissolving PLGA polymer and the drug in a water-immiscible organic solvent (typically dichloromethane or ethyl acetate); (2) Emulsifying this organic phase in an aqueous solution containing a stabilizer (commonly polyvinyl alcohol - PVA) using high-speed homogenization or sonication to form an oil-in-water emulsion; (3) evaporating the organic solvent under reduced pressure with continuous stirring to solidify the nanoparticles; (4) Collecting nanoparticles by ultracentrifugation and washing to remove residual solvents and stabilizers [5]. This method enables control over particle size through parameters such as homogenization speed/sonication energy, surfactant concentration, and organic-to-aqueous phase ratio.

Chitosan Nanoparticle Preparation via Ionic Gelation Ionic gelation is the most prevalent method for chitosan nanoparticle formation, leveraging the electrostatic interaction between chitosan's cationic amino groups and polyanionic cross-linkers. The standard procedure includes: (1) Dissolving chitosan in a dilute acidic aqueous solution (typically 1% acetic acid) to protonate the amino groups; (2) Preparing a separate aqueous solution of a polyanionic cross-linker, most commonly tripolyphosphate (TPP); (3) Adding the TPP solution dropwise to the chitosan solution under constant magnetic stirring at room temperature, leading to instantaneous gelation via electrostatic cross-linking; (4) Continuing stirring to allow nanoparticle maturation [3]. Critical parameters affecting nanoparticle characteristics include the chitosan molecular weight and degree of deacetylation, chitosan-to-TPP mass ratio, pH conditions, and stirring speed.

Characterization Data and Analytical Techniques

Comprehensive characterization of polymeric nanoparticles is essential for quality control and predictive performance assessment. Key parameters include size, surface charge, morphology, drug loading efficiency, and in vitro release profile.

Table 3: Standard Characterization Techniques for Polymeric Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Analytical Technique | Protocol Details | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size Distribution | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [1] | Measurement of particle Brownian motion | Affects circulation time, biodistribution, cellular uptake |

| Surface Charge | Zeta Potential Analysis [1] | Measurement of electrophoretic mobility | Predicts colloidal stability and biological interactions |

| Particle Morphology | Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [1] | High-resolution imaging | Reveals nanoparticle shape and internal structure |

| Chemical Structure | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) [1] | Analysis of polymer and drug signals | Confirms polymer composition and drug conjugation |

| Drug Loading | HPLC/UV-Vis Spectroscopy [2] | Measurement of drug content after extraction | Determines encapsulation efficiency and loading capacity |

| In Vitro Release | Dialysis Method [4] | Sampling and analysis of released drug over time | Predicts in vivo release kinetics and duration |

Recent studies have provided quantitative performance comparisons. A comprehensive analysis of PLGA microparticles encompassing 321 in vitro release studies demonstrated that formulation parameters significantly impact release characteristics, with polymer molecular weight (typically 12-75 kDa) and lactide:glycolide ratio (commonly 50:50 or 75:25) being primary determinants [4]. Research on chitosan nanoparticles has highlighted their exceptional mucoadhesive properties, with studies demonstrating up to 3-5 times improved bioavailability for drugs delivered via nasal and oral mucosal routes compared to conventional formulations [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Polymeric Nanoparticle Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA Polymer | Primary matrix for nanoparticle formation | Controlled release formulations, injectable depots [4] |

| Chitosan | Natural polymer carrier | Mucosal delivery, wound healing applications [3] |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Stabilizer/surfactant in emulsion methods | Prevents aggregation during PLGA nanoparticle formation [5] |

| Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | Ionic crosslinker for chitosan | Forms nanoparticles via ionic gelation [3] |

| Dichloromethane | Organic solvent for polymer dissolution | Solvent in emulsion-solvent evaporation method [5] |

| Acetic Acid | Solubilizing agent for chitosan | Protonates amino groups for aqueous dissolution [3] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Surface modifier for stealth properties | PEGylation to prolong circulation time [5] |

| Coumarin-6 | Fluorescent tracer for imaging | Tracking cellular uptake and biodistribution [1] |

Research Workflow and Experimental Design

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for polymeric nanoparticle research and development.

Contextualizing Polymeric Nanoparticles vs. Liposomal Formulations

In the broader landscape of nanomedicine research, polymeric nanoparticles represent a distinct category alongside lipid-based systems, particularly liposomes. While both are versatile drug delivery platforms, they exhibit fundamental differences in composition, structure, and functional characteristics. Liposomes are spherical vesicles composed of concentric phospholipid bilayers enclosing aqueous compartments, structurally mimicking biological membranes [7] [8]. This architecture allows for simultaneous encapsulation of both hydrophilic drugs (within the aqueous core) and hydrophobic drugs (within the lipid bilayers) [7].

The historical development and clinical translation of these systems have followed different trajectories. Liposomes have a longer history of clinical use, with pioneering products like Doxil (doxorubicin-loaded liposomes) establishing the clinical viability of nanocarriers [8]. Their modular composition, typically including phospholipids and cholesterol, provides excellent biocompatibility but can present stability challenges [7]. Polymeric nanoparticles, particularly PLGA-based systems, offer superior stability and more tunable drug release profiles, with degradation kinetics that can be precisely controlled through polymer composition [2].

A significant advancement for both platforms has been the implementation of PEGylation—the surface attachment of polyethylene glycol chains—to create "stealth" nanoparticles that evade immune recognition and prolong circulation half-life [8] [5]. For liposomes, this addresses rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system, while for polymeric nanoparticles, it enhances bioavailability and target site accumulation [8] [5]. Current research in both fields is increasingly focused on active targeting strategies through surface functionalization with ligands that recognize specific receptors overexpressed on target cells [7] [5].

PLGA and chitosan nanoparticles represent two advanced platforms within the broader category of polymeric drug delivery systems, each with distinctive advantages tailored to specific therapeutic applications. PLGA's superior controlled release capabilities, tunable degradation kinetics, and extensive regulatory approval history make it ideal for sustained-release formulations, particularly for chronic conditions requiring long-term therapy [4] [2]. Chitosan's natural origin, inherent mucoadhesiveness, antimicrobial properties, and permeability-enhancing effects position it as an excellent candidate for mucosal delivery systems and localized therapies [3] [2].

The future trajectory of polymeric nanoparticle development is likely to focus on several key areas: First, the creation of hybrid systems that combine advantageous properties of multiple polymers, such as PLGA-chitosan composites that offer both controlled release and enhanced mucosal adhesion [2]. Second, the development of "smart" nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties that release their payload in response to specific pathological triggers such as pH, enzyme activity, or temperature [1]. Third, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches to accelerate nanoparticle design and optimization, as demonstrated by recent efforts to create comprehensive datasets of PLGA formulation parameters [4]. Finally, increased attention to sustainable nanocarrier design principles, including green synthesis methods and environmentally benign materials, will likely shape future research directions [6].

When positioned within the comprehensive landscape of nanomedicine platforms, polymeric nanoparticles offer distinct advantages in stability and controlled release compared to lipid-based systems, while liposomes maintain benefits in encapsulation versatility and clinical track record. The continued refinement of both platforms, along with the emergence of increasingly sophisticated hybrid approaches, promises to significantly advance targeted therapeutic interventions across a broad spectrum of human diseases.

Liposomes, spherical vesicles comprising one or more phospholipid bilayers enclosing an aqueous core, stand as a cornerstone in drug delivery systems. Their architecture, mimicking biological membranes, confers exceptional biocompatibility and the unique ability to encapsulate both hydrophilic (in the aqueous core) and hydrophobic (within the lipid bilayer) therapeutic agents [9] [10]. Since their discovery, liposomes have been extensively researched and commercialized, with formulations like Doxil paving the way for targeted and sustained drug delivery [10]. Within the broader thesis of analyzing polymeric nanoparticles versus liposomal formulations, it is crucial to understand that the performance of liposomes is not merely a function of their vesicular structure but is profoundly governed by their molecular composition and the physical state of the lipid bilayer [11] [12]. This guide objectively unpacks the critical roles of phospholipid bilayers, cholesterol, and membrane fluidity in shaping the critical quality attributes (CQAs) of liposomal formulations, providing direct comparisons with polymeric nanoparticle systems where pertinent experimental data exists.

Composition and Structure: The Liposome Framework

The Phospholipid Bilayer Foundation

The primary structural component of a liposome is the phospholipid bilayer. These amphiphilic lipids spontaneously assemble into bilayers in an aqueous environment, forming a barrier that separates the internal volume from the external medium [10]. The choice of phospholipid—such as the commonly used phosphatidylcholine (PC)—is a critical formulation decision, as it influences fundamental properties like membrane rigidity, surface charge, and biocompatibility [13]. Notably, phospholipids are not biologically inert; recent studies demonstrate that liposomes composed of palmitoyl oleoyl phosphatidylcholine (POPC) can significantly modulate gene expression in macrophages, particularly upregulating inflammatory pathways via NF-κB activation [13].

Cholesterol: The Membrane Stabilizer

Cholesterol is a ubiquitous and crucial component integrated into the phospholipid bilayer. Its role extends far beyond a simple structural filler. Cholesterol modulates membrane fluidity and stability by inserting itself between the phospholipid hydrocarbon chains, restricting their motion and increasing the packing density of the bilayer [14] [13]. This action leads to a more mechanically robust membrane that is less permeable to water-soluble molecules and reduces the risk of liposome fusion or aggregation during storage [9]. Furthermore, its incorporation is biologically relevant; studies show that including free cholesterol (30%) in POPC liposomes significantly attenuates the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response they would otherwise induce in macrophages [13]. This effect is specific to free cholesterol and is not observed with esterified or water-soluble forms, highlighting a functional role beyond mere structural support [13].

Table 1: Key Components of Liposomal Formulations and Their Functions

| Component | Type | Primary Function | Impact on Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phospholipids (e.g., POPC) | Structural Lipid | Forms the foundational bilayer structure [13] [10]. | Determines intrinsic membrane fluidity, charge, and biocompatibility. Can influence immunogenicity [13]. |

| Cholesterol | Membrane Stabilizer | Modulates fluidity and reduces permeability [14] [13]. | Enhances physical stability, reduces drug leakage, and can suppress inflammatory responses [13]. |

| PEGylated Lipids | Functional Excipient | Creates a hydrophilic "stealth" corona around the liposome [9]. | Prolongs circulation time by reducing opsonization and recognition by the immune system [9]. |

Comparative Performance: Liposomes vs. Polymeric Nanoparticles

Direct comparative studies provide valuable insights into the relative strengths and weaknesses of liposomal and polymeric nanoparticle formulations. A 2020 study directly compared L-carnitine-loaded liposomes (lipo-carnitine) with poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles (nano-carnitine), characterizing their physicochemical properties and release profiles [11]. The data reveal a clear trade-off between particle characteristics and encapsulation efficiency.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of L-Carnitine-loaded Liposomes vs. PLGA Nanoparticles [11]

| Formulation | Particle Size (nm) | Polydispersity Index (PDI) | Zeta Potential (mV) | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipo-carnitine (Liposome) | 97.88 ± 2.96 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | +6.36 ± 0.54 | 14.26 ± 3.52 |

| Nano-carnitine (PLGA) | 250.90 ± 6.15 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | -32.80 ± 2.26 | 21.93 ± 4.17 |

The data shows that the liposomal formulation achieved a smaller particle size and a near-neutral surface charge, while the polymeric PLGA nanoparticles offered superior drug encapsulation and a more monodisperse size distribution (lower PDI) [11]. Both systems successfully transformed the rapid-release profile of free L-carnitine (90% release within 1 hour) into a controlled-release profile sustained over 12 hours, demonstrating their efficacy as delivery systems [11].

Another study on nose-to-brain delivery of meloxicam found that solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), a subtype of lipid nanoparticles, showed higher encapsulation efficiency and drug loading than PLGA nanoparticles. Furthermore, chitosan-coated SLNs demonstrated superior in vitro release, mucoadhesion, and permeation behavior compared to both PLGA NPs and the native drug [12].

Membrane Fluidity: A Pivotal Critical Quality Attribute

Membrane fluidity describes the dynamic, lateral movement and flexibility of lipid molecules within the bilayer [14]. It is a central CQA that acts as a measurable indicator of bilayer behavior, directly impacting drug release kinetics, stability, and biological interactions [14]. Fluidity should not be confused with the phase transition temperature (Tm); rather, it is a reflection of the membrane's physical state at a given temperature.

Experimental Assessment of Fluidity

Fluidity is most practically assessed using fluorescence-based probes, which offer high sensitivity and are amenable to high-throughput screening [14]. Common probes include:

- DPH (1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene): A hydrophobic probe that aligns with the fatty acid chains, reporting on the order of the acyl chain region.

- Laurdan (6-lauroyl-2-dimethylaminonaphthalene): Sensitive to the polarity of its environment, it can distinguish between gel (ordered) and liquid crystalline (disordered) phases through Generalized Polarization (GP) measurements [14].

Factors Governing Membrane Fluidity

Membrane fluidity is influenced by a complex, interdependent set of factors, which form the basis of rational formulation design [14]:

- Cholesterol Content: Increasing cholesterol concentration up to ~30-50% generally reduces fluidity by restricting phospholipid chain motion, leading to a more condensed and stable membrane [14] [13].

- Lipid Acyl Chain Length and Saturation: Shorter chains and a higher degree of unsaturation (double bonds) in fatty acids increase fluidity by reducing intermolecular interactions and introducing kinks that prevent tight packing.

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase the kinetic energy of lipids, thereby increasing membrane fluidity.

- PEGylated Lipids: The incorporation of PEG-lipids can increase the viscosity of the membrane surface and influence fluidity, albeit in a complex manner that depends on the PEG chain length and density [14].

Diagram 1: Factors influencing membrane fluidity and its impact on performance.

Advanced Applications and Synergistic Systems

The understanding of liposomal components has enabled the development of advanced, hybrid nanomedical applications. A prominent example is the synergy between gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and lipid membranes. Functionalizing AuNPs with lipid membranes significantly enhances their biocompatibility and stability in biological environments, reducing cytotoxicity and mitigating rapid clearance by the immune system [15]. Furthermore, this combination unlocks theranostic (therapeutic + diagnostic) capabilities. Membrane-embedded AuNPs can act as nanoscale heaters, enabling spatiotemporally controlled drug release through light-triggered lipid phase transitions, a property not achievable by either component alone [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Liposome Research and Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Formulation | Experimental Application / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylcholines (e.g., POPC) | Primary phospholipid for bilayer formation [13]. | Provides a biocompatible, zwitterionic backbone. A common choice for model membranes. |

| Cholesterol | Membrane stabilizer and fluidity modulator [14] [13]. | Use free cholesterol, not esterified forms, for incorporation into the bilayer for optimal effect on membrane properties and inflammatory response suppression [13]. |

| PEGylated Phospholipids (e.g., DSPE-PEG) | Confers "stealth" properties to prolong circulation half-life [9]. | Critical for reducing protein adsorption and rapid clearance. A key component in mRNA COVID-19 vaccines [9]. |

| Fluorescent Probes (e.g., DPH, Laurdan) | Molecular sensors for biophysical characterization [14]. | Essential for experimentally quantifying membrane fluidity and phase behavior via fluorescence spectroscopy. |

| Cationic Lipids | Enables encapsulation of nucleic acids (DNA, mRNA) via charge interaction. | Core component of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for gene delivery and vaccines [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol: Assessing the Anti-inflammatory Effect of Cholesterol

This protocol is derived from experiments demonstrating cholesterol's ability to attenuate liposome-induced inflammation [13].

Liposome Preparation:

- Prepare two liposome batches using a mini-extruder: one with 100% POPC and another with a 70:30 molar ratio of POPC to free cholesterol.

- Dry the lipid mixtures from chloroform under a nitrogen stream and hydrate the film in endotoxin-free Tris buffer (pH 7.4).

- Extrude the suspension 15 times through a 100 nm membrane filter.

- Purify via ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g, 60 min, 4°C) and resuspend in sterile PBS.

- Characterize size and concentration using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) and ensure endotoxin levels are below 0.01 EU/mL.

Cell Treatment and Analysis:

- Culture macrophage cell lines (e.g., RAW264.7 or J774A.1).

- Incubate cells with equal amounts (e.g., based on lipid mass) of POPC and POPC-Cholesterol liposomes for a set period (e.g., 6 hours).

- Quantify the inflammatory response by measuring TNF-α expression levels using RT-qPCR or ELISA.

- Investigate the mechanism by analyzing NF-κB activation, for instance, via Western blot for phosphorylated NF-κB subunits.

Protocol: Investigating Drug Release Kinetics

This protocol outlines a general approach for conducting in vitro release (IVR) studies, a critical CQA test [16].

Formulation Screening:

- Prepare a series of liposomal formulations varying key parameters (e.g., cholesterol content from 0% to 40%, different phospholipid saturations).

IVR Test Setup:

- Use a standardized apparatus such as a dialysis system or sample-and-separate method.

- Select appropriate release media (e.g., PBS at pH 7.4) and maintain at a constant physiological temperature (37°C) with continuous stirring.

- Place the liposome formulation in a dialysis bag or directly into the release medium.

Sampling and Analysis:

- At predetermined time intervals, withdraw aliquots of the release medium and replace with fresh medium to maintain sink conditions.

- Analyze the drug concentration in the samples using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC, UV-Vis spectroscopy).

- Calculate the cumulative percentage of drug released over time.

Data Modeling:

- Fit the obtained release data to kinetic models (e.g., Weibull, Higuchi, zero-order) to understand the release mechanism.

- Use machine learning workflows to correlate formulation parameters with the resulting release profiles for accelerated development [16].

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for liposomal formulation characterization.

The performance of liposomal formulations is intricately linked to their nanoscale architecture and composition. The phospholipid bilayer provides the foundational structure, while cholesterol serves as a critical modulator of membrane fluidity, stability, and even biological interactions. As demonstrated by direct comparative studies, liposomes often provide distinct advantages in terms of size and surface charge compared to polymeric nanoparticles like PLGA, which may offer superior encapsulation efficiency and monodispersity [11] [12]. A deep understanding of membrane fluidity as a pivotal CQA enables formulators to rationally design liposomes with optimized drug release profiles, stability, and therapeutic efficacy. The ongoing integration of advanced techniques, including machine learning for predicting release profiles [16] and the development of hybrid systems like AuNP-lipid composites [15], continues to push the boundaries of liposomal technology in nanomedicine.

In the field of nanomedicine and drug delivery, the structural architecture of carrier systems is a critical determinant of their performance. This guide provides an objective comparison of two fundamental structural classifications: unilamellar versus multilamellar vesicles in liposomal systems, and solid versus core-shell matrices in polymeric nanoparticles. Understanding these distinctions is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal nanocarrier for specific therapeutic applications, balancing factors such as drug loading, release kinetics, stability, and biological interactions. The systematic analysis presented here, supported by experimental data and protocols, aims to inform rational design choices in pharmaceutical development.

Vesicle Architectures: Unilamellar vs. Multilamellar

Liposomal vesicles are primarily classified based on their lamellar structure, which significantly influences their drug encapsulation capacity, release profile, and biological activity.

Structural Characteristics and Experimental Performance

Table 1: Structural and Functional Comparison of Vesicle Architectures

| Parameter | Unilamellar Vesicles (ULV) | Multilamellar Vesicles (MLV) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Definition | Single phospholipid bilayer surrounding an aqueous core [10] | Multiple concentric phospholipid bilayers separated by aqueous compartments [10] |

| Typical Size Range | 20 nm to >1 μm [10] | Typically larger, often exceeding 1 μm [10] |

| Drug Encapsulation | Hydrophilic drugs in aqueous core; hydrophobic drugs in lipid bilayer [10] | Higher capacity for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs due to multiple compartments |

| Antibody Response (PFC) | Vigorous; Significantly higher than MLV-BSA [17] | Vigorous; lower than ULV-BSA [17] |

| Key Advantage | More efficient contact with immune cells due to simpler structure [17] | Higher encapsulation capacity for some compounds |

Experimental Evidence and Protocol

A seminal study directly compared the effectiveness of Multilamellar Vesicles (MLV) and Unilamellar Vesicles (ULV) in enhancing specific antibody formation [17].

- Vesicle Preparation: MLV and ULV were composed of dimyristoyl-lecithin, cholesterol, and dicetyl phosphate in a molar ratio of 7:2:1. Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) was used as the model antigen, and liposome-associated BSA was purified via Blue Sepharose CL-6B column chromatography [17].

- Structural Confirmation: Electron microscopy was used to confirm the presence of appropriate lamellar structures for each preparation [17].

- In Vivo Evaluation: Mice were injected with either free BSA, empty vesicles, or liposome-associated BSA (MLV-BSA or ULV-BSA). The plaque-forming cell (PFC) response was measured to quantify the specific antibody formation [17].

- Key Finding: While both liposome-associated BSA formulations generated a vigorous PFC response, the magnitude of the response induced by BSA entrapped in unilamellar vesicles was significantly higher than that in multilamellar vesicles. This suggests the lamellar arrangement plays a crucial role in affecting the potentiated antibody response, potentially due to more efficient cellular processing of the simpler ULV structure [17].

Experimental Workflow for Vesicle Comparison

Polymeric Matrices: Solid vs. Core-Shell

Polymeric nanoparticles offer an alternative to lipid-based systems, with their own structural classifications that govern functionality. The primary distinction lies between solid matrix systems and core-shell architectures.

Structural Definitions and Comparative Performance

Table 2: Structural and Functional Comparison of Polymeric Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Solid Matrix Systems (SLNs) | Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) | Core-Shell Polymeric Hybrids (PLNs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Definition | Solid lipid matrix at room temperature [18] [10] | Mixed solid and liquid lipid matrix, creating an imperfect structure [18] [10] | Polymeric core surrounded by a lipid/PEG shell [19] |

| Drug Loading Capacity | ~80% for HCT [18] | ~90% for HCT [18] | High, due to combined polymer-lipid structure [19] |

| Drug Release (300 min) | ~65% of HCT released [18] | >90% of HCT released [18] | Controlled release from polymeric core [19] |

| Storage Stability (6 mo) | ~15% drug loss [18] | <5% drug loss [18] | High physical and storage stability [19] |

| Key Advantage | Biocompatibility, solid matrix protection [18] [10] | Superior drug loading and stability vs. SLNs [18] | Combines stability of polymers with biocompatibility of lipids [19] |

Core-Shell Structures: Solid vs. Hollow

A further distinction within core-shell architectures is the nature of the core itself. Solid Core-Shell (SCs-MIP) structures have a solid interior, while Hollow Core-Shell (HCs-MIP) structures possess an empty interior space [20].

- Diffusion Performance: Research on molecularly imprinted polymers has demonstrated that the diffusion coefficient (D) of probe molecules in HCs-MIP is approximately 1.5 times higher than in SCs-MIP. This enhancement is attributed to the bilateral mass diffusion of analyte or probe molecules from both the outer and inner interfaces of the MIP layer [20].

- Analytical Application: This superior diffusion profile makes hollow core-shell structures particularly advantageous for applications requiring high sensitivity, such as electrochemical sensing of anti-HIV drugs like Lamivudine (3TC) and Zidovudine (AZT) [20].

Diffusion Pathways in Core-Shell Structures

Experimental Protocol for Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation

The following methodology details the preparation and optimization of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs), as used in a study on the diuretic drug Hydrochlorothiazide (HCT) for pediatric therapy [18].

1. Material Screening:

- Solubility Studies: The solubilizing power of various solid lipids (e.g., Precirol ATO5, Compritol 888 ATO) and liquid lipids (e.g., Transcutol HP, Miglyol 812) towards HCT is assessed. For solid lipids, drug solubility is visually estimated in the melted lipid. For liquid lipids, equilibrium solubility is determined after 24 hours at 65°C [18].

- Compatibility Studies: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) is used to analyze the compatibility between the drug and formulation components by scanning physical mixtures under static air [18].

2. Nanoparticle Preparation:

- The Hot High-Shear Homogenization (HSH) technique is employed.

- The lipid phase (solid lipid alone for SLNs, or a blend of solid and liquid lipids for NLCs) is heated to 65°C to melt.

- An aqueous surfactant phase (containing surfactants like Gelucire 44/14, Tween 80, or Pluronic F68) is heated to the same temperature.

- The aqueous phase is dispersed into the lipid phase using high-shear homogenization (e.g., at 10,000 rpm for 5-10 minutes) to form a pre-emulsion.

- The resulting pre-emulsion is further processed by ultrasonication to reduce particle size and achieve a uniform dispersion [18].

3. Characterization:

- Particle Size & PDI: Dynamic light scattering measures mean particle diameter and polydispersity index (PDI).

- Zeta Potential: Laser Doppler electrophoresis assesses surface charge.

- Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%): Determined by quantifying the amount of successfully entrapped drug versus the initial total amount.

- In Vitro Release Study: The drug release profile is evaluated using dialysis membranes in a suitable release medium under sink conditions [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Nanoparticle Formulation and Evaluation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Lipids | Precirol ATO5, Compritol 888 ATO, Glyceryl Monostearate (Geleol) [18] | Forms the solid matrix of SLNs and the solid part of NLCs; determines drug loading and release kinetics. |

| Liquid Lipids | Transcutol HP, Caprylic/Capric Triglycerides (Miglyol, Labrafac) [18] | Creates imperfections in the solid lipid matrix of NLCs to improve drug loading and prevent expulsion. |

| Surfactants | Gelucire 44/14, Tween 80, Pluronic F68, Poloxamer 188 [18] | Stabilizes the nanoparticle dispersion during and after formation; critical for controlling particle size and stability. |

| Phospholipids | DSPC, DOPE, HSPC [21] [19] | Primary component of liposomal bilayers and the lipid shell in hybrid systems; provides biocompatibility. |

| Biodegradable Polymers | PLGA, PLGA-mPEG [11] [19] | Forms the core of polymeric and hybrid nanoparticles; degrades in the body to provide controlled drug release. |

| PEGylated Lipids | DMG-PEG, DSG-PEG, ALC-0159 [21] [19] | Creates a "stealth" coating on nanoparticles to reduce immune clearance and prolong circulation half-life. |

| Cationic Lipids | DLin-MC3-DMA, ALC-0315, SM-102 [21] | Enables encapsulation of nucleic acids (mRNA, siRNA) in lipid nanoparticles via electrostatic interaction. |

The choice between unilamellar and multilamellar vesicles or solid and core-shell polymeric matrices is not a matter of superiority but of application-specific optimization. Unilamellar vesicles demonstrate advantages in scenarios requiring efficient biological interaction, such as adjuvant activity, while multilamellar vesicles offer higher encapsulation capacity. In the polymeric domain, solid lipid nanoparticles provide a robust and biocompatible platform, but nanostructured lipid carriers and advanced core-shell systems like polymeric lipid hybrid nanoparticles (PLNs) address limitations in drug loading and stability. The emerging class of hollow core-shell particles further extends functionality by enhancing mass transport. The experimental data and protocols summarized in this guide provide a foundation for researchers to make informed decisions in the design and development of next-generation nanomedicines.

In the evolving landscape of nanomedicine, polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) and liposomal formulations have emerged as frontrunner drug delivery systems. Both platforms are designed to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of active pharmaceutical ingredients, yet they are distinguished by their unique structural compositions, core characteristics, and subsequent performance in biological environments. Polymeric nanoparticles are typically solid colloidal particles fabricated from natural or synthetic polymers, whereas liposomes are spherical vesicles comprising one or more phospholipid bilayers surrounding an aqueous core [22] [23]. This fundamental architectural difference dictates their interactions with biological systems, their capacity to encapsulate diverse therapeutic agents, and their inherent stability profiles.

The selection of an appropriate nanocarrier is a critical determinant in the success of a drug product. For researchers and drug development professionals, a clear, data-driven understanding of the inherent advantages and limitations of each system is indispensable for matching the carrier to the therapeutic application. This guide provides a comparative analysis of PNPs and liposomes, focusing on the three pivotal axes of biocompatibility, encapsulation capacity, and initial stability, supported by experimental data and standardized protocols to inform early-stage formulation development.

Comparative Analysis: Core Characteristics at a Glance

The table below summarizes the fundamental properties of polymeric nanoparticles and liposomes, providing a high-level overview of their key characteristics.

Table 1: Inherent Properties of Polymeric Nanoparticles and Liposomal Formulations

| Characteristic | Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNPs) | Liposomal Formulations |

|---|---|---|

| Core Composition | Solid polymer matrix (e.g., PLGA, Chitosan) [24] [25] | Phospholipid bilayer(s) enclosing an aqueous core [23] [26] |

| Structural Versatility | Nanospheres, nanocapsules, polymeric micelles [24] | Unilamellar, Oligolamellar, Multilamellar Vesicles [26] |

| Biocompatibility | Ranges from excellent (natural polymers) to tunable (synthetic polymers); degradation byproducts may require evaluation [24] [25] | Generally excellent due to biomimetic lipid composition; high biological acceptance [23] [26] |

| Encapsulation Drive | Hydrophobic interactions, polymer-drug affinity, and physical entrapment within a solid matrix [22] [1] | Partitioning based on drug solubility: hydrophobic (bilayer) vs. hydrophilic (aqueous core) [23] [8] |

| Typical Drug Loading Capacity | Can be very high, particularly for hydrophobic drugs within the polymer matrix [24] | Moderate; constrained by bilayer volume/area for lipophilic drugs and core volume for hydrophilic drugs [23] |

| Inherent Physical Stability | Generally high; solid matrix minimizes drug leakage and offers robust colloidal stability [1] [27] | Can be lower; susceptible to drug leakage, fusion, and aggregation over time without formulation optimization [23] [28] |

Deep Dive into Key Performance Parameters

Biocompatibility and Biological Interaction

Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNPs): The biocompatibility of PNPs is intrinsically linked to the polymer choice. Natural polymers like chitosan and gelatin are prized for their excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and low toxicity [25]. Synthetic polymers such as PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) are widely used because they are biodegradable and biocompatible, with degradation products (lactic and glycolic acids) that are metabolized via normal physiological pathways [24] [27]. However, the potential for cytotoxicity or immune responses must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, particularly for novel synthetic polymers or specific degradation byproducts [22].

Liposomal Formulations: Liposomes exhibit superior biocompatibility from the outset, as they are typically composed of phospholipids and cholesterol, molecules that are natural components of biological membranes [23] [26]. This biomimetic nature makes them well-tolerated, minimally immunogenic, and biodegradable. Their surface charge can be tailored (cationic, anionic, or neutral) to influence cellular interactions, with cationic liposomes sometimes showing increased cytotoxicity compared to their anionic or neutral counterparts [26].

Encapsulation Capacity and Loading Strategies

Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNPs): PNPs offer significant versatility in encapsulation. Their solid matrix is highly effective at encapsulating hydrophobic drugs with high loading capacity, protecting them from the aqueous environment [24]. A key advantage is the ability to achieve controlled and sustained drug release profiles based on polymer erosion and diffusion mechanisms [22]. Furthermore, PNPs can be engineered as "smart" systems that respond to specific stimuli (e.g., pH, temperature, enzymes) for precise drug release at the target site [22] [1]. For instance, a study on pH-responsive PLGA NPs demonstrated a drug loading capacity of 1.8 wt% for a modified doxorubicin, leveraging the hydrophobic core for efficient encapsulation [27].

Liposomal Formulations: Liposomes possess a unique amphiphilic structure that allows for the simultaneous encapsulation of both hydrophilic drugs (within the aqueous core) and hydrophobic drugs (within the lipid bilayer) [23] [8]. However, their loading capacity is constrained by the finite volumes of these compartments. A primary strategy to enhance loading, particularly for hydrophilic drugs, is active (remote) loading, which uses transmembrane ion or pH gradients to trap ionizable drugs inside the liposome at high concentrations [23]. Experimental data for sesquiterpene lactones encapsulated in liposomes demonstrated encapsulation efficiencies of approximately 70-80%, highlighting the effectiveness of passive incorporation for lipophilic molecules [28].

Table 2: Experimental Encapsulation and Stability Data from Case Studies

| Formulation Detail | Polymeric Nanoparticle (ATRAM-BSA-PLGA) [27] | Liposomal Formulation (Soybean PC) [28] |

|---|---|---|

| Encapsulated Agent | Doxorubicin-TPP (hydrophobic) | Eremantholide C / Goyazensolide (lipophilic) |

| Reported Loading/EE | Loading Capacity: 1.8 wt% | Encapsulation Efficiency: ~70-80% |

| Stability Conditions | In cell culture medium with 10% FBS for 72 hours | Storage at 4°C over 12 months; simulated GI fluids |

| Key Stability Finding | Hydrodynamic diameter remained stable with only a modest ~30 nm increase in 50% serum. | Substance concentration remained stable over 12 months; stable in simulated gastric & intestinal fluids. |

| Implied Advantage | High stability in biologically relevant media; minimal drug leakage. | Good long-term storage stability and resilience to physiological pH environments. |

Initial Stability Profile

Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNPs): PNPs generally exhibit superior physical stability. Their solid polymeric core is highly effective at preventing the rapid leakage of encapsulated drugs, a challenge often faced by other nanocarriers [1]. The covalent cross-linking in some PNP designs, such as the BSA-wrapped PLGA NPs, further enhances encapsulation stability and prevents premature drug release, even in the presence of serum proteins [27].

Liposomal Formulations: The stability of liposomes is a well-documented challenge. They can be prone to physical instability, including aggregation, fusion, and drug leakage, which can be triggered by temperature variations, mechanical stress, or interaction with biological fluids [23]. Chemically, phospholipids are susceptible to hydrolysis and oxidation, which can compromise the integrity of the bilayer [23]. Consequently, liposomal formulations often require sophisticated optimization, such as lyophilization (freeze-drying) with cryoprotectants for long-term storage, and surface modifications like PEGylation to improve stability in circulation [23] [8].

Essential Experimental Protocols for Characterization

To generate reproducible and comparable data on these nanocarriers, researchers must adhere to standardized characterization protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for two fundamental assays.

Protocol for Determining Encapsulation Efficiency (EE) and Drug Loading (DL)

This protocol is adapted from procedures used in the cited research for both PNPs and liposomes [27] [28].

- Separation of Unencapsulated Drug: Separate the nanocarriers (PNPs or liposomes) from the free, unencapsulated drug. This is typically achieved using dialysis, ultracentrifugation, or size-exclusion chromatography.

- Destruction of Nanocarriers and Drug Extraction: Lyse the separated nanocarrier pellet or suspension to release the encapsulated drug. Methods include:

- Solvent Disruption: Add an organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol, or isopropanol) appropriate for the drug and carrier to dissolve the lipid bilayer (liposomes) or polymer matrix (PNPs). Vortex vigorously and/or sonicate to ensure complete disruption.

- Detergent Lysis: For liposomes, use a detergent like Triton X-100 to dissolve the lipid membrane.

- Quantification of Encapsulated Drug: Analyze the resulting solution using a calibrated analytical technique, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or UV-Vis Spectrophotometry, to determine the concentration of the encapsulated drug (C_encapsulated).

- Quantification of Total Drug: Directly analyze a separate, non-purified sample of the formulation (often after dissolution/lysis as in Step 2) to determine the total drug concentration (C_total).

- Calculation:

- Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%) = (Cencapsulated / Ctotal) × 100%

- Drug Loading (DL%) = (Mass of encapsulated drug / Total mass of the nanoparticle formulation) × 100%

Protocol for Assessing In Vitro Colloidal Stability

This assay evaluates the nanoparticle's ability to maintain its size and polydispersity under storage or physiological conditions, a key indicator of aggregation and physical stability [27] [28].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the nanocarrier formulation (PNP or liposome) in the desired medium to a suitable concentration for dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement. Relevant media include:

- Storage buffer (e.g., PBS at 4°C, 25°C, 37°C).

- Biologically relevant fluids (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cell culture medium, simulated gastric/intestinal fluid).

- Incubation: Incubate the samples under controlled conditions (temperature, agitation) for a predetermined period (e.g., 24 hours, 72 hours, 1 month).

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Measurement: At designated time points, analyze each sample using a DLS instrument (Zetasizer).

- Measure the hydrodynamic diameter (nm).

- Measure the polydispersity index (PDI), which indicates the breadth of the size distribution. A PDI < 0.2 is generally considered monodisperse.

- Measure the zeta potential (mV) in a suitable electrolyte to assess surface charge stability.

- Data Analysis: Plot the mean diameter and PDI over time. A stable formulation will show minimal change in size and a consistently low PDI. A significant increase in diameter and/or PDI indicates aggregation and poor colloidal stability.

Visualizing Characterization Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in the characterization workflow for evaluating nanocarrier stability and encapsulation.

Diagram 1: A generalized experimental workflow for the initial characterization of nanocarriers, highlighting the parallel assessment of encapsulation parameters and physical stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Formulation and Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Relevant Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA | A biodegradable synthetic polymer forming the core matrix of PNPs; allows for controlled drug release. | Polymeric Nanoparticles [27] |

| Chitosan | A natural polysaccharide polymer; confers biocompatibility, mucoadhesion, and permeation enhancement. | Polymeric Nanoparticles [25] |

| Soybean Phosphatidylcholine (SPC) | A natural phospholipid mixture; primary building block for forming the lipid bilayer of liposomes. | Liposomes [28] |

| Cholesterol | Incorporated into lipid bilayers; modulates membrane fluidity and stability, reducing drug leakage. | Liposomes [23] [26] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-Lipid | Used for surface PEGylation; confers "stealth" properties by reducing opsonization and extending circulation half-life. | Liposomes (Stealth) [8] |

| Dialysis Tubing / Filters | For purifying formulated nanocarriers by separating them from unencapsulated free drug. | Both [28] |

| Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | A polyanionic cross-linking agent used in ionic gelation to form chitosan nanoparticles. | Polymeric Nanoparticles [25] |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | For critical quality attribute measurement: hydrodynamic particle size, PDI, and zeta potential. | Both [1] [28] |

Both polymeric nanoparticles and liposomal formulations offer distinct and powerful tools for advanced drug delivery. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic alignment with the therapeutic agent and the target product profile. Polymeric nanoparticles excel with high loading capacity for hydrophobic drugs, robust physical stability, and tunable, stimuli-responsive release kinetics. Liposomal formulations offer unparalleled biocompatibility, the unique ability to co-deliver hydrophilic and hydrophobic agents, and a well-established pathway for clinical translation, albeit with greater inherent challenges regarding physical and chemical stability. A deep understanding of these inherent advantages and limitations, coupled with rigorous characterization using standardized protocols, provides the foundational knowledge required to navigate the complex landscape of nanocarrier selection and optimization.

Synthesis, Engineering, and Therapeutic Deployment in Disease Targeting

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) represent a cornerstone of modern nanomedicine, enabling advancements in drug delivery, bioavailability, and targeted therapy. Their clinical translation hinges on the selection and optimization of fabrication techniques that dictate critical quality attributes such as particle size, polydispersity, drug loading, and encapsulation efficiency. This guide provides a systematic comparison of three principal fabrication methods—solvent evaporation, nanoprecipitation, and microfluidics—focusing on their operational principles, resultant nanoparticle characteristics, and experimental protocols. Within the broader context of polymeric nanoparticles versus liposomal formulations research, understanding these techniques is critical for rational design of drug delivery systems. The reproducibility and scalability offered by microfluidic systems present a significant advantage over conventional bulk methods, directly addressing batch-to-batch variability challenges that have long hindered nanomedicine translation [29].

Technical Comparison of Fabrication Methods

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key fabrication techniques for polymeric nanoparticles.

| Fabrication Method | Key Mechanism | Typical Particle Size (nm) | Polydispersity Index (PDI) | Drug Loading Capacity | Encapsulation Efficiency | Scalability | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Evaporation [30] | Emulsification of polymer solution into aqueous phase followed by solvent removal | 150 – 300 | Broad (High) | Moderate | Moderate for hydrophilic drugs (double emulsion) | Moderate (batch process) | Suitable for hydrophilic drugs (W/O/W) | High polydispersity, batch-to-batch variability |

| Nanoprecipitation (Batch) [31] [32] | Solvent displacement and polymer precipitation upon mixing with anti-solvent | 100 – 250 | Moderate to Broad | Moderate | Low to Moderate | Moderate (batch process) | Simplicity, no need for high-energy mixing | Low encapsulation efficiency for hydrophilic drugs |

| Microfluidics [29] [31] [30] | Hydrodynamic flow focusing for controlled mixing and nanoprecipitation | 50 – 200 (tunable) | Narrow (Low, <0.1) | High | High (~90%) [30] | High (continuous process) | Superior reproducibility, precise size control, continuous production | Low initial production rate, requires specialized equipment |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Solvent Evaporation (Double Emulsion Method)

The double emulsion (water-in-oil-in-water, W/O/W) solvent evaporation technique is particularly suited for encapsulating hydrophilic drugs [30].

- Primary Emulsion Formation: An aqueous solution containing the hydrophilic active (e.g., a peptide or protein) is added to an organic phase containing the dissolved polymer (e.g., PLGA in dichloromethane, DCM). This mixture is subjected to high-speed homogenization or probe sonication to form a stable primary water-in-oil (W/O) emulsion.

- Secondary Emulsion Formation: The primary W/O emulsion is immediately transferred into a large volume of an external aqueous phase containing an emulsifier (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol, PVA). This secondary emulsification is typically performed using a high-speed mechanical stirrer to form a double (W/O/W) emulsion.

- Solvent Evaporation & Hardening: The double emulsion is stirred for several hours to allow the organic solvent to evaporate, solidifying the polymer and forming solid nanoparticles. The hardened nanoparticles are then collected by ultracentrifugation and washed repeatedly with purified water to remove residual solvents and emulsifiers.

Batch Nanoprecipitation

Batch nanoprecipitation relies on the spontaneous formation of nanoparticles upon the displacement of a water-miscible solvent from a polymer solution [32].

- Organic Phase Preparation: The polymer (e.g., PLGA or PLA) and the hydrophobic drug are co-dissolved in a water-miscible organic solvent such as acetone or acetonitrile. This constitutes the organic phase.

- Anti-Solvent Mixing: The organic phase is introduced, typically via syringe pump or dropwise addition under moderate magnetic stirring, into a larger volume of an anti-solvent (water, often containing a stabilizer like Poloxamer 188 or polysorbate 80).

- Nanoparticle Self-Assembly: Upon mixing, the organic solvent rapidly diffuses into the aqueous phase, reducing the solvent quality for the polymer. This leads to supersaturation, nucleation, and the spontaneous formation of solid nanoparticles as the polymer and drug precipitate out.

- Solvent Removal & Purification: The residual organic solvent is removed from the nanoparticle suspension under reduced pressure or by dialysis. The final PNPs are obtained through filtration or centrifugation.

Microfluidic-Assisted Nanoprecipitation

Microfluidic fabrication uses chip-based devices to achieve highly controlled and reproducible mixing, overcoming the limitations of bulk methods [31] [30].

- Device Setup: A common configuration is a glass or PDMS cross-shaped microfluidic chip. Syringe pumps are used to precisely control the flow rates of the fluid streams.

- Hydrodynamic Flow Focusing: The organic phase (polymer and drug in a water-miscible solvent) is injected through the central inlet. The aqueous phase (water with surfactant) is introduced through the two side inlets at a significantly higher flow rate. This geometry "focuses" the organic stream into a narrow thread, enabling rapid and uniform diffusion of the solvent into the anti-solvent.

- Continuous Nanoparticle Formation: The controlled mixing triggers nanoprecipitation in a confined region of the chip, producing nanoparticles with narrow size distribution. The nanoparticles are collected in a reservoir at the outlet in a continuous manner.

- Key Parameter Control: The Flow Rate Ratio (FRR), defined as the aqueous phase flow rate divided by the organic phase flow rate, is a critical parameter. A higher FRR typically results in smaller nanoparticle sizes due to faster mixing [31].

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for PNP fabrication.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Example Uses & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | Biodegradable polymer matrix | Most common polymer; FDA-approved; lactide:glycolide ratio tunes degradation rate [30]. |

| PVA (Polyvinyl Alcohol) | Surfactant/Stabilizer | Used in solvent evaporation to prevent coalescence of emulsion droplets [31]. |

| Poloxamer 188 (Pluronic F68) | Surfactant/Stealth agent | Used in nanoprecipitation and microfluidics; provides steric stabilization and can impart "stealth" properties [31]. |

| Vitamin E TPGS (d-α-tocopheryl PEG succinate) | Surfactant/Stabilizer | Effective stabilizer for nanoprecipitation; can enhance drug encapsulation and efficacy [31]. |

| Acetone | Water-miscible solvent | Common solvent for nanoprecipitation and microfluidics due to its rapid diffusion into water [31] [32]. |

| DCM (Dichloromethane) | Water-immiscible solvent | Standard solvent for single and double emulsion (solvent evaporation) methods [30]. |

| Syringe Pumps | Fluid driving system | Essential for microfluidic setups and controlled batch nanoprecipitation to ensure precise, pulsation-free flow rates. |

Data, Workflows, and Visualization

Comparative Performance Data

Experimental data consistently demonstrates the superiority of microfluidics in producing monodisperse PNPs. A direct comparison of PLGA nanoparticles fabricated via bulk mixing versus microfluidic nanoprecipitation showed a significant reduction in Polydispersity Index (PDI) from over 0.2 in bulk to below 0.1 using a microfluidic chip [31]. Furthermore, microfluidic encapsulation of drugs like Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel has been reported to achieve encapsulation efficiencies exceeding 90%, a substantial improvement over many batch processes [30].

Microfluidic Nanoprecipitation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the controlled workflow and mechanism of nanoparticle formation in a microfluidic flow-focusing device.

Size Distribution Comparison

This diagram provides a conceptual comparison of the particle size distributions characteristic of each fabrication method.

The choice of fabrication technique for polymeric nanoparticles is a critical determinant of their performance and translational potential. While solvent evaporation and batch nanoprecipitation remain valuable for specific applications, microfluidic-assisted nanoprecipitation stands out for its unparalleled control over particle characteristics, high reproducibility, and continuous operation mode. The ability of microfluidics to produce monodisperse populations of PNPs with high encapsulation efficiency directly addresses the key challenges of batch-to-batch variability and inefficient drug loading that plague conventional methods. For researchers engaged in the comparative analysis of polymeric versus liposomal nanocarriers, the precision and data-rich nature of microfluidic fabrication provide a robust platform for generating reliable and clinically relevant formulations. Future advancements will likely focus on scaling out microfluidic production through device parallelization and integrating smart, data-driven optimization to fully realize the promise of polymeric nanomedicines [29] [32].

In the evolving field of nanomedicine, the development of effective drug delivery systems is paramount for enhancing therapeutic outcomes. Among the various nanocarriers, liposomes—spherical vesicles composed of phospholipid bilayers—stand out for their biocompatibility, ability to encapsulate diverse cargo, and well-established clinical use [33] [34]. Their exploration is often framed within a broader thesis that compares them with other platforms, notably polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs). While PNPs offer superior stability and highly tunable polymer chemistry for controlled release [1], liposomes possess the distinct advantage of a biomimetic structure that closely resembles cell membranes, facilitating fusion and cellular uptake [8]. This guide provides an objective comparison of three fundamental liposome preparation techniques: Thin-Film Hydration, Ethanol Injection, and Reverse-Phase Evaporation. The selection of a preparation method is a critical first step in nanocarrier design, as it directly influences key performance parameters such as particle size, encapsulation efficiency, and suitability for scale-up, thereby dictating the vehicle's potential for success in pre-clinical and clinical applications [33] [35].

Experimental Protocols for Liposome Preparation

Thin-Film Hydration (Bangham Method)

The Thin-Film Hydration method is the most classical and widely used technique for forming multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) [36] [37].

- Step 1: Lipid Dissolution. Dissolve 2–20 mg of lipids (e.g., DPPC or POPC) in 2–4 mL of a chloroform/methanol mixture (3:7, v/v) within a round-bottom rotary flask [36].

- Step 2: Thin Film Formation. Evaporate the organic solvent using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure (200–300 mbar) at a temperature of 35–45 °C in a water bath. This deposits a thin lipid film on the inner wall of the flask. For complete solvent removal, further dry the film under high vacuum (5–10 mbar) until a constant weight is achieved [36].

- Step 3: Hydration. Pre-heat the lipid film and an aqueous buffer solution above the transition temperature (Tm) of the lipids. Add the buffer to the flask to achieve a final lipid concentration of 0.5–10 mg/mL. Hydrate the film for 45 minutes with occasional vigorous shaking and brief sonication in an ultrasonic bath (≈30 s/sonication) to detach the film and form MLVs [36].

- Step 4: Post-Processing (Optional). The resulting heterogeneous MLVs can be processed into small or large unilamellar vesicles (SUVs or LUVs) using downsizing techniques such as sonication (using a probe sonicator on ice) or extrusion (passing the MLVs multiple times through a polycarbonate membrane with a defined pore size) [37].

Ethanol Injection

This method is rapid and simple, favoring the formation of unilamellar vesicles with minimal solvent residue concerns [37].

- Step 1: Lipid Dissolution. Dissolve the phospholipids in ethanol [37].

- Step 2: Rapid Injection. Pre-heat an aqueous medium containing the material to be encapsulated. Rapidly inject the ethanolic lipid solution through a needle into the stirred aqueous media [37].

- Step 3: Vesicle Formation and Solvent Removal. The spontaneous self-assembly of lipids into liposomes occurs instantly due to the change in polarity as the ethanol mixes with the aqueous phase. Stir the mixture at an elevated temperature (55–65 °C) to facilitate the evaporation of residual ethanol [37]. The final liposome size (SUVs or LUVs) is influenced by the rate of injection and the volume of ethanol, with volumes not exceeding 7.5% of the total formulation volume favoring homogeneous SUVs [37].

Reverse-Phase Evaporation

This technique is particularly noted for achieving high encapsulation efficiencies for hydrophilic molecules [37].

- Step 1: Emulsion Formation. Dissolve lipids in an organic solvent such as chloroform/methanol (2:1 v/v). Add an aqueous buffer containing the drug to be encapsulated to the lipid solution and sonicate the mixture to form a stable water-in-oil emulsion [37].

- Step 2: Solvent Evaporation. Remove the organic solvent by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure. This process transforms the emulsion first into a viscous gel [37].

- Step 3: Gel Collapse and Liposome Formation. Continued evaporation leads to the collapse of the gel structure, resulting in the formation of a liposomal suspension. The large aqueous core of the original emulsion droplets contributes to the high encapsulation efficiency of this method [37].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the steps of these preparation methods and their resulting liposome types.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Preparation Methods

The choice of preparation method significantly impacts critical quality attributes of the final liposomal formulation. The table below provides a comparative analysis of the three methods based on key performance metrics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Liposome Preparation Methods

| Performance Metric | Thin-Film Hydration | Ethanol Injection | Reverse-Phase Evaporation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Drying & hydration [37] | Polarity change [37] | Emulsion evaporation [37] |

| Typical Liposome Type | Multilamellar Vesicles (MLVs) [36] [37] | Small/Large Unilamellar Vesicles (SUVs/LUVs) [37] | Large Unilamellar Vesicles (LUVs) [37] |

| Encapsulation Efficiency | Low for hydrophilic drugs [37] | Low for lipophilic drugs [37] | High for hydrophilic molecules [37] |

| Size Control | Requires post-processing (e.g., extrusion) [37] | Moderate (depends on injection rate) [37] | Good [37] |

| Scalability | Difficult to scale up [37] | Good for lab-scale, simple [37] | Challenging, time-consuming [37] |

| Residual Solvent | Chloroform/Methanol (difficult to remove) [37] | Ethanol (less toxic, easier to remove) [37] | Chloroform/Methanol (significant amounts) [37] |

| Key Advantage | Simple, highly reproducible [36] [37] | Rapid, simple process [37] | High aqueous encapsulation [37] |

| Key Disadvantage | Low encapsulation efficiency, heterogeneous initial size [37] | Potential for heterogeneous liposomes, solvent dilution [37] | Uses large amounts of organic solvent [37] |

Beyond these conventional methods, novel techniques like microfluidics are emerging. Microfluidic devices allow for the continuous and controlled production of liposomes with a narrow size distribution by mixing lipid solutions in alcohol with an aqueous buffer in a micromixer chip [37]. While this method offers excellent size control and is suitable for a continuous flow process, challenges remain regarding solvent removal and the cost of cartridge renewal [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful liposome formulation relies on a specific set of reagents and instruments. The table below details the essential components of a liposome research toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Liposome Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Liposome Preparation | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phospholipids | Structural backbone of the lipid bilayer. | DPPC: Saturated lipid with high Tm for rigid bilayers [36].POPC: Unsaturated lipid for more fluid bilayers [36].HSPC/DSPC: Common in commercial products for stability [34]. |

| Cholesterol | Bilayer excipient that stabilizes membrane, reduces permeability, and improves in vivo stability [33]. | Typically used at 20-50 mol% relative to phospholipids [33]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-Lipid | Creates "stealth" liposomes; prolongs circulation by reducing RES uptake [33] [8]. | e.g., MPEG-DSPE. Used in Doxil/Caelyx [34]. |

| Organic Solvents | Dissolve lipids for initial processing. | Chloroform/Methanol: Used in thin-film hydration [36].Ethanol: Used in ethanol injection (Class 3, less toxic) [37]. |

| Hydration Buffer | Aqueous medium for hydrating the lipid film, can contain hydrophilic drugs. | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), HEPES, or other buffers at physiological pH and osmolarity [36]. |

| Critical Equipment | Enables formation and sizing of liposomes. | Rotary Evaporator: For solvent removal and thin-film formation [36] [37].Sonicator (Bath/Probe): For downsizing MLVs to SUVs [37].Extruder: For producing homogeneous LUVs/SUVs via membrane extrusion [36] [37]. |

The selection of an optimal liposome preparation method is a critical decision that balances experimental needs with practical constraints. Thin-film hydration remains the gold standard for its simplicity and reproducibility, ideal for initial formulation development despite its need for post-processing sizing. Ethanol injection offers a rapid, straightforward path to unilamellar vesicles with lower solvent toxicity. Reverse-phase evaporation is the method of choice when high encapsulation efficiency for hydrophilic drugs is the primary objective, though it comes with the burden of higher solvent use.

When framing this choice within the broader context of nanocarrier research, the distinct advantages of liposomes—their proven clinical track record and high biocompatibility—are counterbalanced by the potentially superior stability and highly tunable drug release profiles offered by polymeric nanoparticles [38] [1]. Ultimately, the research question, the physicochemical properties of the active compound, and the intended therapeutic application will guide not only the choice of preparation method but also the fundamental selection between liposomal and polymeric nanocarrier platforms. Future advancements will likely focus on hybrid techniques and scalable technologies like microfluidics to overcome current limitations in encapsulation efficiency, solvent residue, and industrial manufacturability [33] [37].

In modern therapeutics, nanocarriers have revolutionized drug delivery by improving the pharmacokinetics and safety profiles of active pharmaceutical ingredients. Among the most prominent of these carriers are liposomal formulations and polymeric nanoparticles, which offer distinct advantages and challenges [8] [39]. Liposomes are spherical phospholipid vesicles with structural similarities to biological membranes, enabling encapsulation of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs [23] [40]. Polymeric nanoparticles, conversely, are typically composed of biodegradable polymers that can provide robust control over drug release kinetics [39]. This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these two platforms, focusing on three critical engineering strategies for enhanced performance: PEGylation for stealth properties, stimuli-responsive mechanisms for controlled release, and active targeting ligands for precision delivery. The objective assessment of experimental data and performance metrics presented herein offers valuable insights for researchers selecting appropriate nanocarrier systems for specific therapeutic applications.

Comparative Analysis of Liposomal and Polymeric Nanoparticle Platforms

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of liposomal versus polymeric nanoparticle platforms

| Characteristic | Liposomal Formulations | Polymeric Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Composition | Phospholipid bilayers (natural/synthetic) with cholesterol [40] | Biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLGA, PEG-PLGA) [39] |

| Architecture | Unilamellar or multilamellar vesicles enclosing aqueous core [23] | Solid matrix or core-shell structures (micelles) [39] |

| Drug Encapsulation | Hydrophilic drugs in aqueous core; hydrophobic drugs in lipid bilayer [23] | Primarily hydrophobic drugs in polymer matrix; conjugation approaches for hydrophilic drugs [39] |

| Biocompatibility | High (biomimetic cellular membrane structure) [40] | Variable (depends on polymer composition) [39] |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Moderate (challenges with batch-to-batch uniformity) [23] | Moderate to high (requires polymer synthesis expertise) [39] |

| Regulatory Approval Status | Multiple FDA-approved products [40] | Limited approved products, though platforms are well-established [39] |

Table 2: Drug loading capacity and encapsulation efficiency comparison

| Parameter | Liposomal Formulations | Polymeric Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Loading Methods | Passive loading, active/remote loading using pH gradients [23] | Nanoprecipitation, emulsification-solvent evaporation [41] |

| Loading Capacity Challenges | Limited for conventional liposomes; improved with advanced strategies [23] | Generally high for hydrophobic drugs; lower for hydrophilic compounds [39] |

| Encapsulation Efficiency | Variable (5-90% depending on method and drug properties) [23] | Typically moderate to high (50-90% for compatible drugs) [39] |

| Strategies for Enhancement | Transmembrane ion gradients, lipid composition optimization, supercritical fluid technologies [23] | Polymer-drug conjugation, surface modification, hybrid systems [39] |