Quantum Dots vs. Organic Dyes: A Comprehensive Efficacy Analysis for Advanced Detection and Biosensing

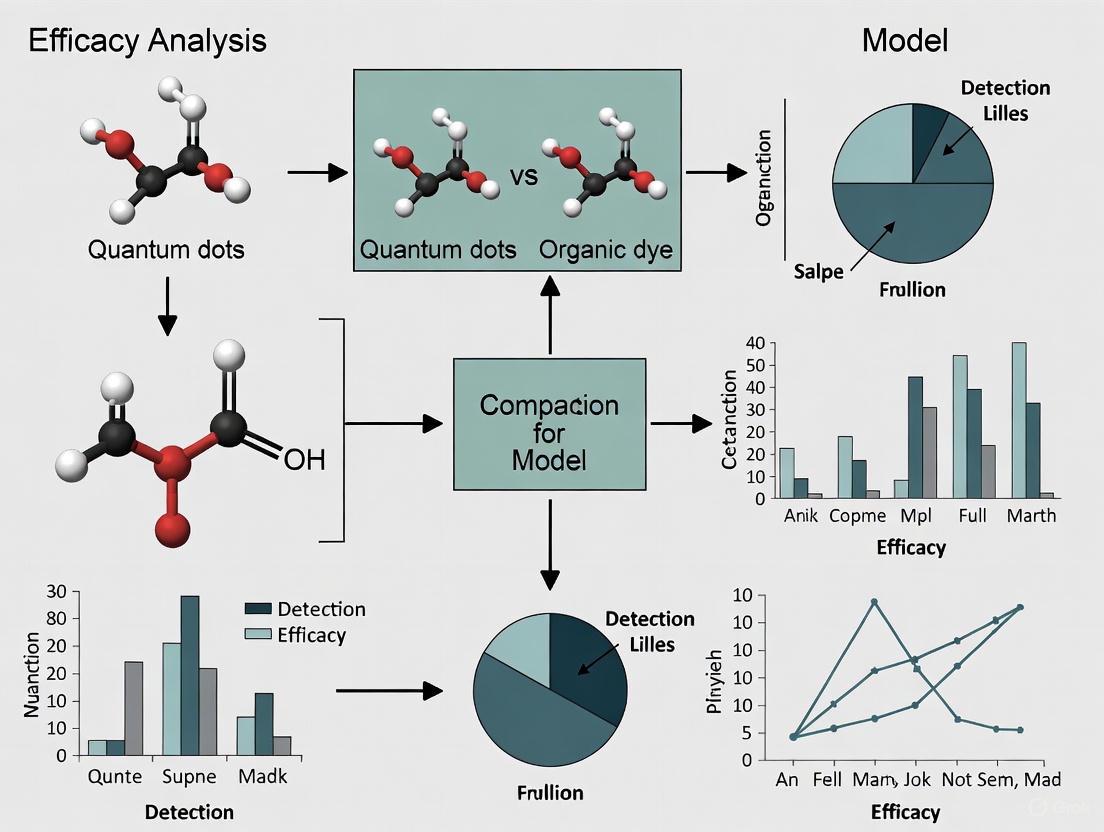

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of quantum dots (QDs) and organic dyes for detection applications, targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantum Dots vs. Organic Dyes: A Comprehensive Efficacy Analysis for Advanced Detection and Biosensing

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of quantum dots (QDs) and organic dyes for detection applications, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles governing the optical properties and performance of both materials. The scope covers synthesis methodologies, functionalization strategies, and specific applications in biomedical diagnostics and biosensing. The analysis addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, including photostability, toxicity, and biocompatibility challenges, and presents a rigorous, data-driven comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and quantification capabilities. The review synthesizes key findings to outline future trajectories for integrating these materials into next-generation diagnostic platforms.

Fundamental Principles: Unveiling the Core Mechanisms of QDs and Organic Dyes

Introduction to Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) as a Key Performance Metric

Photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) is a fundamental parameter that measures the efficiency of a photoluminescent material. It is defined as the ratio of the number of photons emitted to the number of photons absorbed by a substance [1] [2]. A PLQY of 100% indicates that every absorbed photon results in an emitted photon. This metric is crucial for evaluating materials used in applications ranging from biological imaging and medical diagnostics to display technologies and solar cells [1] [3] [4]. For researchers comparing fluorescent tags, PLQY is a primary indicator of brightness and efficiency.

This guide provides an objective comparison between quantum dots (QDs) and organic dyes, focusing on their performance in detection research. We summarize core quantitative data, detail essential experimental protocols, and list critical research reagents to inform material selection for scientific and drug development applications.

Quantum Dots vs. Organic Dyes: A Performance Comparison

The choice between quantum dots and organic dyes involves trade-offs between efficiency, stability, and biocompatibility. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics based on current literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Quantum Dots and Organic Dyes

| Performance Parameter | Quantum Dots (QDs) | Organic Dyes |

|---|---|---|

| Typical PLQY Range | Can exceed 90% [5] | Often ranges from 10% to 70% [5] |

| Photostability | Exceptional resistance to photobleaching [6] [7] | Prone to photobleaching, leading to signal loss [5] [7] |

| Absorption Spectra | Broad absorption spectra [5] | Sharper, more structured absorption peaks |

| Emission Spectra | Tunable, narrow emission based on size and composition [8] [6] | Fixed, relatively broad emission |

| Biocompatibility & Toxicity | Concerns exist due to potential heavy metal content (e.g., Cd); requires careful surface engineering [8] [5] | Generally more biocompatible and suitable for in vivo use [5] |

| Synthesis & Functionalization | Complex synthesis; can be conjugated to antibodies for targeted detection [6] [7] | Relatively simple synthesis and chemical modification [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Evaluation

Robust experimental methodology is essential for a fair comparison of emissive probes. The following sections detail common protocols for measuring PLQY and for conducting a bio-detection assay that highlights the practical differences between QDs and dyes.

Absolute PLQY Measurement Using an Integrating Sphere

The integrating sphere method is considered a direct ("absolute") way to measure PLQY that avoids the need for a reference standard, making it highly versatile for solids, films, and liquids [1] [4].

Detailed Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: The sample (e.g., QD or dye solution, solid film) is placed inside the integrating sphere. A blank control (e.g., pure solvent or blank substrate) is also prepared [2] [4].

- Excitation Wavelength Selection: A monochromatic light source is used. The wavelength is chosen to be well-separated from the sample’s emission spectrum to easily distinguish between scattered excitation light and photoluminescence [4].

- Spectral Measurement:

- The blank is measured first inside the sphere. Its spectrum shows a single peak at the excitation wavelength, quantifying the total number of excitation photons [4].

- The sample is then measured. Its spectrum typically shows two features: the scattered excitation light (reduced in intensity due to absorption by the sample) and the broader photoluminescence emission [4].

- Data Analysis & PLQY Calculation: The PLQY (( \Phi )) is calculated by integrating the relevant areas of the recorded spectra [1] [4]:

- Number of Photons Absorbed ((N{abs})): Determined by subtracting the integral of the scattered excitation light in the sample measurement from the integral of the excitation peak in the blank measurement.

- Number of Photons Emitted ((N{em})): The integral of the sample's emission peak, corrected for any background signal from the blank in the same spectral region.

- The PLQY is then given by: ( \Phi = N{em} / N{abs} ) [4].

Diagram: Workflow for Absolute PLQY Measurement

Fluorescence Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (Fl-NTA) for Bio-Detection

Fluorescence-NTA is a powerful method for characterizing extracellular vesicles (EVs) and other nanoparticles, providing a direct comparison of QDs and dyes in a relevant bio-detection context [7].

Detailed Workflow:

- Probe Conjugation:

- QDs: Antibodies (e.g., against EV markers CD9, CD63) are conjugated to QDs using commercial SiteClick coupling kits. This involves attaching dibenzocyclooctyne (DIBO)-modified QDs to azide-modified antibodies [7].

- Organic Dyes: Antibodies are labeled with dyes like Alexa 488 using standard conjugation chemistry [7].

- Sample Immunolabelling: Isolated EVs are incubated with the QD- or dye-conjugated antibodies. The labeling conditions (antibody concentration, incubation time, temperature) are optimized to ensure specific binding while minimizing non-specific background [7].

- Fl-NTA Measurement: The immunolabeled samples are loaded into the NTA instrument. A laser excites the particles, and a camera tracks their Brownian motion.

- Data Analysis: The software calculates the size and concentration of the detected particles. Sensitivity is evaluated by comparing the number concentration of EVs detected via Fl-NTA for both QDs and dyes. The ability to detect smaller EV populations is also assessed [7].

Diagram: Fl-NTA Experimental Workflow for EV Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials required for the experiments described above, particularly for Fl-NTA-based detection of extracellular vesicles.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | High-brightness, photostable fluorescent probes for labeling and detection. | QD625 nanocrystals for immunolabelling EVs [7]. |

| Organic Dyes | Traditional fluorescent probes for comparison; often less photostable. | Alexa 488 dye for immunolabelling EVs [7]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Bind to target biomarkers (e.g., on EVs) for specific detection. | Anti-human CD9 and CD63 antibodies [7]. |

| Antibody Conjugation Kit | Links fluorophores (QDs or dyes) to antibodies while maintaining activity. | SiteClick Antibody Labelling Kit [7]. |

| Integrating Sphere | Essential accessory for spectrofluorometers to perform absolute PLQY measurements. | Sphere coated with Spectralon for direct PLQY method [1] [3]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA) | Instrument for measuring the size and concentration of nanoparticles in solution. | Used for Scatter- and Fluorescence-NTA of EVs [7]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Reagents | For growing cells that produce the extracellular vesicles to be studied. | RPMI-1640, DMEM, Exosome-Depleted FBS [7]. |

| EV Isolation Reagents | To concentrate and purify vesicles from cell culture media or biofluids. | Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based precipitation reagent [7]. |

The experimental data and protocols presented demonstrate a clear performance trade-off. Quantum dots offer superior photostability and higher PLQY, leading to brighter, more persistent signals that are critical for sensitive, long-term detection assays like Fl-NTA [7]. However, their potential toxicity and more complex conjugation chemistry remain challenges [5]. Organic dyes, while generally less bright and prone to photobleaching, are often more biocompatible and easier to functionalize [5].

The choice between these two classes of emitters depends heavily on the specific application. For demanding, long-duration, or highly multiplexed detection research, QDs may be worth the additional effort. For simpler, shorter-term, or highly sensitive in vivo work, organic dyes may be the preferred option. Understanding their quantified performance, as laid out in this guide, enables researchers to make an informed decision.

Quantum confinement is the fundamental physical effect that gives quantum dots (QDs) their remarkable, size-tunable optical properties. When semiconductor crystal dimensions are reduced to the nanoscale (typically 2-10 nanometers), below a critical threshold known as the Bohr exciton radius, the movement of charge carriers (electrons and holes) becomes spatially restricted in all three dimensions [9] [10]. This confinement leads to discrete energy levels, in contrast to the continuous energy bands found in bulk semiconductors. The resulting phenomenon is a size-dependent bandgap: smaller dots have a wider bandgap, thus requiring more energy for an electron to jump from the valence band to the conduction band [10]. When these excited electrons return to their ground state, they emit light with a frequency directly determined by this energy gap. Consequently, simply by controlling the physical size of the nanocrystal during synthesis, scientists can precisely engineer the color of light it emits, enabling a "rainbow from a single material" [9].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of QDs and traditional organic dyes, focusing on their performance in detection research. We objectively compare their physicochemical properties, present experimental data in structured tables, and detail methodologies to help researchers select the optimal fluorescent label for their specific applications.

Fundamental Properties and Comparative Analysis

The unique optical properties of QDs stem directly from quantum confinement. As the QD size decreases, the bandgap increases, causing a blue-shift in the emission wavelength [10]. For example, CdSe QDs can be tuned to emit across the entire visible spectrum: ~2-3 nm dots emit blue/green light, while ~5-7 nm dots emit red/near-infrared light [10]. This size-tunability provides a significant advantage over organic dyes, whose emission profiles are fixed by their molecular structure.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Quantum Dots versus Organic Dyes

| Property | Quantum Dots | Organic Dyes |

|---|---|---|

| Molar Extinction Coefficient | High (0.5-5 × 10⁶ M⁻¹cm⁻¹) [11] | Lower (∼ 80,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ for fluorescein) [11] |

| Photostability | High; resistant to photobleaching [6] [10] [11] | Low; susceptible to photobleaching [10] [11] |

| Fluorescence Lifetime | Longer (tens of nanoseconds) [11] | Shorter (a few nanoseconds) [11] |

| Action Cross-Section | Very high (∼ 10,000 GM at 1200 nm for PbS QDs) [11] | Lower (e.g., ∼ 6 GM for fluorescein at 800 nm) [11] |

| Stokes Shift | Large (can exceed 100 nm) [12] [11] | Small (typically 20-50 nm) [11] |

| Quantum Yield | High (e.g., 46-69% for CuAlGaSe/ZnS [12]; 50-90% for CdSe/ZnS [6]) | Variable (can be high, but often diminishes upon conjugation) [11] |

A broad absorption profile allows simultaneous excitation of different QD sizes with a single light source, simplifying instrument setup for multiplexed assays. Their narrow, symmetric emission spectra (typically 20-40 nm FWHM) minimize cross-talk between different detection channels [10] [11]. Organic dyes, conversely, have asymmetric, broader emission tails, which can complicate multiplex detection.

Figure 1: The causal chain from nanoscale size reduction to size-tunable emission in quantum dots.

Quantitative Performance Comparison in Detection

In practical diagnostic and sensing applications, the superior photophysical properties of QDs translate into enhanced analytical performance, particularly in sensitivity and the ability to perform multiplexed detection.

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Diagnostic and Sensing Applications

| Application / Metric | Quantum Dot Performance | Organic Dye Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | Femtomolar (10⁻¹⁵ M) biomarker detection [6] [13] | Typically micromolar to nanomolar [11] | Ultra-sensitive identification in complex biological environments [6] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High; simultaneous detection of multiple analytes using different-sized QDs [6] [10] | Limited; broad emission tails cause spectral overlap [11] | Multiplexed biosensing in a single assay [6] |

| Signal Brightness | ~10-20 times brighter than organic dyes [6] | Baseline brightness | Cellular imaging and biomarker labeling [6] [11] |

| Continuous Tracking Duration | Long-term (hours); high photostability [10] [11] | Short-term (seconds-minutes); rapid photobleaching [6] [11] | Real-time tracking of cellular processes [10] |

Quantum dot-infused nanocomposites (QDNCs) represent a significant breakthrough, enabling diagnostic modes such as targeted delivery, signal amplification, and multifunctionality [6] [13]. Their integration into solid-state sensors, such as the paper-based device for hemoglobin quantification, demonstrates their potential for robust, point-of-care diagnostics [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis of High-Quality Quantum Dots

Protocol 1: Hot-Injection Colloidal Synthesis of CdSe QDs [10] [12]

- Objective: To produce high-quality, monodisperse CdSe QDs with precise size control.

- Materials: Cadmium precursor (e.g., CdO), selenium precursor (e.g., trioctylphosphine selenide - TOPSe), coordinating solvents (e.g., 1-octadecene - ODE, oleylamine - OLA), and a ZnS precursor for shell growth.

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Load the cadmium precursor and coordinating solvents in a multi-neck flask. Heat and stir under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon) until a clear solution is obtained.

- Nucleation: Rapidly inject the TOPSe solution into the hot (typically 250-320°C) reaction mixture. This causes a sudden supersaturation, leading to instantaneous nucleation.

- Growth: Lower the temperature (typically 250-300°C) to allow for controlled growth of the nanocrystals. The reaction time is a key parameter for controlling final QD size.

- Shell Growth (Core/Shell): For enhanced quantum yield and stability, a wider bandgap shell (e.g., ZnS) can be grown epitaxially around the CdSe core by successively adding shell precursors at a lower temperature.

- Purification: Cool the reaction mixture. Precipitate the QDs using a non-solvent (e.g., ethanol or acetone), followed by centrifugation. Redisperse the purified QDs in a non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane or toluene) [10].

- Data Interpretation: The size and concentration of CdSe QDs can be determined from their absorption spectrum, using the position of the first excitonic peak and established empirical relationships [11].

Surface Functionalization for Bioimaging

Protocol 2: Ligand Exchange and Bioconjugation for Aqueous Solubility and Targeting [10]

- Objective: To render hydrophobic QDs water-soluble and conjugate them with biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, peptides) for specific targeting.

- Materials: Hydrophobic QDs in organic solvent, hydrophilic ligands (e.g., dihydrolipoic acid - DHLA, mercaptopropionic acid - MPA), bioconjugation reagents (e.g., EDC, NHS), and the targeting biomolecule.

- Procedure:

- Ligand Exchange:

- Mix the native hydrophobic QDs with an excess of the hydrophilic ligand.

- The new ligands, containing thiol groups, displace the original hydrophobic ones on the QD surface via stronger coordinate covalent bonding.

- Precipitate and centrifuge the QDs to remove excess ligands and by-products. Redisperse the now water-soluble QDs in an aqueous buffer (e.g., borate or phosphate buffer) [10].

- Bioconjugation (EDC/NHS Chemistry):

- Activate the carboxyl groups on the QD surface by reacting with EDC and NHS in an aqueous buffer (e.g., MES buffer, pH ~6).

- Purify the activated QDs to remove excess EDC/NHS.

- Mix the activated QDs with the biomolecule (e.g., an antibody containing primary amine groups) and allow the coupling reaction to proceed for several hours.

- Purify the final QD-bioconjugate using size-exclusion chromatography or filtration to remove unbound biomolecules [10].

- Ligand Exchange:

- Validation: The success of bioconjugation can be validated using techniques like gel electrophoresis (shift in mobility) or ELISA to confirm retained biological activity.

Figure 2: Key steps for functionalizing quantum dots for biological applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation with QDs requires specific materials and an understanding of their functions. The following table lists key solutions and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Quantum Dot Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Core/Shell Precursors | Forms the inorganic nanocrystal. | CdO, ZnCl₂, TOPSe, (TMS)₂S [10]. Choice determines core optical properties. |

| Coordinating Solvents | Controls crystal growth, prevents aggregation. | 1-Octadecene (ODE), Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO), Oleylamine (OLA) [10] [12]. |

| Ligands for Water Solubility | Renders QDs dispersible in aqueous buffers for bio-applications. | Dihydrolipoic Acid (DHLA), Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA), PEG-based ligands [10]. Thiol groups bind to the QD surface. |

| Bioconjugation Reagents | Covalently links biomolecules to the QD surface. | EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-Hydroxysuccinimide) for carboxyl-amine coupling [10]. |

| Targeting Biomolecules | Confers molecular specificity to the QD probe. | Antibodies, peptides, aptamers [6] [10]. Defines the application target (e.g., cancer biomarker). |

| Matrix Materials | Enhances stability/functionality in diagnostic devices. | Silica, polymers, magnetic nanoparticles used in nanocomposites [6] [13]. |

Quantum dots, governed by the principle of quantum confinement, offer a suite of advantages over traditional organic dyes, including superior brightness, photostability, and the unique capability for multiplexed detection due to their size-tunable emission. While challenges regarding toxicity and complex surface chemistry persist, ongoing research into cadmium-free alternatives and improved surface modification strategies is steadily addressing these issues [6] [9] [10]. The choice between QDs and organic dyes ultimately depends on the specific requirements of the experiment. For long-term, highly sensitive, and multiplexed detection studies, QDs are often the superior tool. Their continued development and integration into nanocomposites and point-of-care devices are poised to set a new standard for precision diagnostics and bioimaging [6] [13].

Fluorescence detection remains one of the most sensitive and powerful tools in chemical analysis and biological imaging, with organic fluorescent dyes serving as fundamental components in these applications [15]. The inherent properties of these dyes—derived from their specific chromophore systems and molecular structures—dictate their performance across various scientific and industrial contexts. Organic chromophores, characterized by their systems of conjugated double bonds and functional groups, form the molecular foundation for light absorption and emission in fluorescent dyes [16]. Understanding these intrinsic properties is particularly crucial when comparing traditional organic dyes with emerging alternatives such as quantum dots (QDs), especially within efficacy analyses for detection research where performance characteristics directly impact experimental outcomes [17] [18].

This guide objectively examines the fundamental properties of organic dyes, focusing on the chromophores and molecular features that govern their fluorescent behavior. We present experimental data comparing their performance against quantum dots and detail methodologies for characterizing key optical properties, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for informed probe selection in detection applications.

Fundamental Properties and Performance Comparison

Defining Characteristics of Organic Dyes

Organic fluorescent dyes are characterized by several key molecular and optical properties that determine their functionality in detection systems. The chromophore, a central molecular component consisting of conjugated π-electron systems, is responsible for light absorption and often defines the dye's fundamental color characteristics [15]. These conjugated systems delocalize electrons across multiple atoms, creating molecular orbitals with energy separations that correspond to the energy of visible or ultraviolet light.

The fluorescence lifetime of organic dyes typically ranges from a few nanoseconds, which is similar to the autofluorescence decay time of biological samples, potentially complicating signal discrimination in biological imaging [19]. Stokes shift—the energy difference between absorbed and emitted photons—is generally smaller in organic dyes compared to quantum dots, which can lead to self-interference through reabsorption effects in some experimental configurations [19]. Perhaps most notably, organic dyes frequently suffer from photobleaching—the irreversible decomposition of the fluorophore under optical excitation—which limits their usefulness in long-term imaging studies or applications requiring prolonged signal stability [19].

Quantitative Performance Comparison: Organic Dyes vs. Quantum Dots

Table 1: Performance characteristics of organic dyes versus quantum dots

| Property | Organic Dyes | Quantum Dots | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extinction Coefficient | ~105 M-1cm-1 [16] | 0.5–5 × 106 M-1cm-1 [20] | Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry [16] |

| Fluorescence Lifetime | Several nanoseconds [19] | 20–50 nanoseconds [19] | Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy [16] |

| Photostability | High susceptibility to photobleaching [19] | High resistance to photobleaching [19] | Continuous excitation monitoring fluorescence intensity [19] |

| Stokes Shift | Relatively small [19] | Large [19] | Emission and excitation wavelength difference [19] |

| Emission Bandwidth | 50–100 nm FWHM [16] | 20–40 nm FWHM [21] | Bandwidth at half maximum of emission spectrum [16] |

| Signal Brightness | Reference standard | ~20x brighter than Rhodamine 6G [19] | Comparative fluorescence intensity measurement [19] |

Table 2: Absorption and emission properties of organic chromophores from experimental database

| Organic Chromophore Core | Typical Absorption Max (nm) | Typical Emission Max (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (ε max) | Fluorescence Quantum Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coumarin | 300-400 [16] | 400-500 [16] | Data available in database [16] | Data available in database [16] |

| BODIPY | 450-550 [16] | 500-600 [16] | Data available in database [16] | Data available in database [16] |

| Perylene | 450-550 [16] | 500-600 [16] | Data available in database [16] | Data available in database [16] |

| Porphyrin | 400-450, 500-650 [16] | 600-700 [16] | Data available in database [16] | Data available in database [16] |

| Tetraphenylethene | 300-400 [15] | 400-550 [15] | Data available in database [16] | Varies with aggregation state [15] |

The experimental database of optical properties for organic compounds provides extensive characterization data for 7,016 unique chromophores across 365 solvents or solid states, enabling researchers to select dyes with precise optical characteristics for their specific applications [16].

Experimental Protocols for Property Characterization

Determining Absorption and Emission Properties

Protocol 1: Measuring Absorption and Emission Spectra

Sample Preparation: Prepare dilute solutions (typically 1-10 μM) of the organic dye in appropriate solvents. Use solvents without significant absorbance in the spectral region of interest [16].

Instrumentation: Utilize ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry for absorption measurements and spectrofluorimetry for emission spectra [16].

Absorption Measurement: Record UV-Vis spectrum from 200-800 nm. Identify the first absorption maximum wavelength (λabs, max) and calculate the extinction coefficient (εmax) using the Beer-Lambert law with known concentration [16].

Emission Measurement: Using the absorption maximum as guidance, select an appropriate excitation wavelength. Scan emission from λabs, max to 800 nm to identify the emission maximum wavelength (λemi, max) [16].

Bandwidth Calculation: Determine the full width at half maximum (FWHM) for both absorption and emission spectra, reporting in either nm or cm⁻¹ [16].

Protocol 2: Determining Fluorescence Quantum Yield

Reference Selection: Choose a standard fluorophore with known quantum yield (e.g., quinine sulfate or rhodamine 6G) with excitation and emission characteristics similar to the test sample [16].

Solution Preparation: Prepare dilute solutions of both sample and reference with matched absorbance (<0.1) at the excitation wavelength to minimize inner filter effects [22].

Measurement: Record emission spectra of both sample and reference solutions using the same instrument parameters.

Calculation: Apply the following equation:

(YX = YS \times (FX / FS) \times (AS / AX) \times (ηX^2 / ηS^2))

Where Y is quantum yield, F is integrated fluorescence intensity, A is absorbance at excitation wavelength, and η is refractive index of solvent. Subscripts X and S denote unknown and standard, respectively [22].

Assessing Photostability and Environmental Sensitivity

Protocol 3: Photostability Testing

Sample Preparation: Prepare dye solutions or labeled specimens at working concentrations.

Continuous Irradiation: Expose samples to continuous illumination at appropriate excitation wavelength, monitoring fluorescence intensity over time [19].

Quantification: Record the time required for fluorescence intensity to decay to 50% of its initial value (photobleaching half-time) or quantify the rate of intensity loss per unit time [19].

Comparison: Compare against reference materials (e.g., Rhodamine 6G for organic dyes) or alternative fluorophores under identical conditions [19].

Protocol 4: Solvatochromism Assessment

Solvent Series: Prepare identical concentrations of the dye in a series of solvents with varying polarity (e.g., hexane, toluene, THF, acetonitrile, water) [16].

Spectral Recording: Measure absorption and emission spectra in each solvent under identical instrument parameters.

Shift Quantification: Calculate the spectral shift in cm⁻¹ between polar and non-polar solvents to quantify solvatochromic response [16].

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The fluorescence process in organic dyes follows a well-defined photophysical pathway that begins with light absorption and culminates in photon emission. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for predicting dye behavior in complex detection systems.

The Jablonski diagram above illustrates the fundamental photophysical processes in organic fluorophores. Following light absorption that promotes electrons from the ground state (S₀) to excited singlet states (S₁, S₂), several competing pathways determine the ultimate fluorescence efficiency. Vibrational relaxation rapidly returns molecules to the lowest vibrational level of S₁, from which fluorescence emission occurs as electrons return to S₀. Competing non-radiative decay pathways dissipate energy as heat, while intersystem crossing can populate triplet states (T₁) that may lead to phosphorescence or photobleaching through reactive oxygen species generation [23] [15].

Advanced Material Design and Aggregation Effects

Nanomaterial Engineering and Aggregation Behavior

Recent advances in organic dye applications have focused on nanomaterial formulations that enhance performance characteristics. Self-assembled fluorescent nanomaterials based on small-molecule organic dyes combine the spectral tunability and biocompatibility of molecular fluorophores with the brightness and stability of inorganic materials [15]. These sophisticated architectures range from simple dye aggregates to core-shell nanoarchitectures involving hyperbranched polymers.

A significant challenge in organic dye nanomaterial design has been aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ)—where fluorescent molecules undergo self-quenching in concentrated solutions or aggregates due to reabsorption and energy transfer processes [15]. This phenomenon has prompted the development of dyes exhibiting aggregation-induced emission (AIE), where molecules demonstrate weak emission in solution but bright fluorescence in solid state or aggregates [15]. Examples include fluorophores incorporating tetraphenylethene (TPE) or triphenylamine motifs, which exhibit restricted intramolecular rotation in aggregated states that suppresses non-radiative decay pathways [15].

Table 3: Research reagent solutions for organic dye studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Core Chromophores | Coumarin, Perylene, BODIPY, Tetraphenylethene [16] [15] | Light absorption/emission; spectral tuning via core modification |

| Solvent Systems | Cyclohexane, THF, Acetonitrile, Water [16] | Solvatochromism studies; environmental sensitivity assessment |

| Reference Standards | Quinine sulfate, Rhodamine 6G [16] | Quantum yield determination; instrument calibration |

| AIEgens | Tetraphenylethene (TPE), Triphenylamine derivatives [15] | Nanoparticle formulation; aggregation-induced emission applications |

| Polymeric Matrices | Amphiphilic block copolymers, Hyperbranched polymers [15] | Nanomaterial encapsulation; colloidal stability improvement |

The inherent properties of organic dyes—governed by their chromophore systems and molecular structures—provide both opportunities and limitations in detection research. While quantum dots offer superior photostability, brightness, and narrow emission profiles for certain applications [19] [20], organic dyes maintain distinct advantages in biocompatibility, synthetic versatility, and established conjugation chemistry. The development of advanced organic nanomaterials with AIE characteristics and the availability of comprehensive optical property databases [16] continue to expand the utility of organic dyes in sophisticated detection systems.

For researchers conducting efficacy analyses in detection applications, selection between organic dyes and quantum dots should consider specific experimental requirements including sensitivity needs, observation duration, spectral multiplexing demands, and biological compatibility. The experimental protocols and performance data presented here provide a foundation for systematic evaluation of these fluorescent probes within targeted detection research contexts.

The efficacy of fluorescent probes in detection research, encompassing applications from bio-imaging to biosensing, is fundamentally governed by their core optical properties: absorption, emission, and the Stokes shift. Within this domain, two primary classes of materials—organic dyes and quantum dots (QDs)—exhibit distinct photophysical behaviors. This guide provides an objective comparison of these materials, framing the analysis within the context of their application in detection research for scientists and drug development professionals. The comparative data and experimental methodologies outlined herein are intended to serve as a foundational reference for the selection and application of these probes in complex biological environments.

Core Optical Properties and Comparative Performance Metrics

The performance of a fluorophore is quantified by several key parameters. The absorption spectrum defines the range of light wavelengths a material can absorb. The emission spectrum characterizes the light released upon returning to the ground state. The energy difference between the absorption maximum and emission maximum is the Stokes shift, a critical property for minimizing self-absorption and signal cross-talk in multiplexed assays [24]. Other vital metrics include the Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY), which measures emission efficiency, and photostability, which defines resistance to photobleaching.

The following tables summarize the comparative performance of organic dyes and quantum dots based on current research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Optical Properties between Organic Dyes and Quantum Dots

| Optical Property | Organic Dyes | Quantum Dots | Impact on Detection Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Spectrum | Narrow, structured peaks [25] | Broad, continuous spectrum [19] | QDs allow single-wavelength excitation of multiple colors, simplifying experimental setup [19]. |

| Emission Spectrum | Broad, asymmetric tails [19] | Narrow, symmetric (typically 20–40 nm FWHM) [19] | Narrow QD emission enables simultaneous multiplexing with minimal spectral overlap [19]. |

| Stokes Shift | Typically small (e.g., 20-30 nm) [25] | Can be engineered to be very large (e.g., >150 nm) [26] | Large Stokes shift in QDs drastically reduces reabsorption, improving signal clarity in dense samples or large-scale devices like luminescent solar concentrators [26] [25]. |

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Variable; can be high but often environment-sensitive | Can be very high (e.g., >90% for core-shell structures) [27] | High QY provides brighter signals, enhancing detection sensitivity [27] [19]. |

| Photostability | Generally low; prone to rapid photobleaching [19] | Very high; resistant to photobleaching [19] | Superior QD photostability enables long-term tracking and time-lapse experiments [19]. |

| Brightness | Moderate | Very high (product of high extinction coefficient and high QY) [19] | High brightness allows for the detection of low-abundance targets [19]. |

Table 2: Exemplary Performance Data for Specific Fluorophores

| Material Type & Name | Absorption Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Stokes Shift (nm) | PLQY (%) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Dye: Cy7-CA [25] | ~700 | ~727 | 27 | Not Specified | NIR harvesting transparent luminescent solar concentrators |

| Organic Dye: Rhodamine-based [24] | Modeled | Modeled | Predicted: 5-30 nm error | Not Specified | General fluorescent tagging and sensing |

| QD: ZnSe:Mn²⁺/ZnS (d-C/S) [26] | ~426 | ~596 | 170 | 83.3% | Luminescent solar concentrators with zero reabsorption |

| QD: CdSe/ZnS-TPP [27] | Varies by size | Varies by size | Not Specified | 90.0% (Blue) - 96.1% (Red) | High-resolution patterning for light-emitting diodes |

| QD: Carbon Dots [28] | Broad UV | Broad, excitation-dependent | Large | Generally lower than semiconductor QDs | Biocompatible imaging and sensing |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Machine Learning Prediction of Stokes Shift in Organic Dyes

This protocol is based on a study predicting Stokes shifts for 3066 fluorescent organic materials [24].

- Objective: To accurately predict the Stokes shift of fluorescent organic dyes based on molecular structure and solvent properties, enabling rapid screening prior to synthesis.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Dataset: A curated set of 3066 individual records of fluorescent organic materials, including molecular structures and solvent conditions [24].

- Software: Machine learning libraries for Python/R (e.g., scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM).

- Methodology:

- Data Pre-processing: Encode the chemical structure of dyes and solvents using Morgan fingerprints (also known as circular fingerprints). This converts molecular structures into a numerical format usable by machine learning models [24].

- Model Training: Split the dataset into a training set (90%) and a test set (10%). Train hybrid cascade machine learning models, such as the combination of Extreme Gradient Boosting Regression (XGBR) and Light Gradient Boosting Machine Regression (LGBMR) [24].

- Validation: Validate model performance using the test set. The best-performing model (XGBR + LGBMR) achieved a root mean squared error (RMSE) of 19.95 nm and a coefficient of determination (R²) of 86.18% [24]. Further experimental validation was performed by comparing predicted values with measured Stokes shifts of synthesized xanthene dyes (Rh-19, Rh-B, Rh-6G, Rh-110) [24].

Protocol 2: Synthesis and Characterization of Large Stokes Shift Quantum Dots

This protocol details the synthesis of Mn-doped ZnSe/ZnS QDs with a large Stokes shift [26].

- Objective: To synthesize heavy-metal-free quantum dots with a large Stokes shift to mitigate reabsorption losses for applications in luminescent solar concentrators.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Precursors: Zinc oleate, manganese oleate, selenium powder.

- Shell Precursors: Sources for ZnS shell growth.

- Solvents: 1-Octadecene, oleic acid.

- Ligands: Trioctylphosphine (TOP).

- Methodology:

- Doped-Core Synthesis (Nucleation Doping): Synthesize ZnSe:Mn²⁺ core QDs by heating precursors in a non-coordinating solvent. Optimize the Mn²⁺ concentration (e.g., 5%) to maximize PLQY [26].

- Shell Growth: Overcoat the ZnSe:Mn²⁺ core with a wider bandgap ZnS shell to enhance confinement and passivate surface defects. This step significantly increases PLQY (from 30.5% to 83.3%) and causes a slight redshift in emission [26].

- Optical Characterization:

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Measure absorption spectra to identify the first exciton peak.

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Measure emission spectra. The Mn²⁺ dopant gives a characteristic broad emission at ~596 nm from the ⁴T₁ → ⁶A₁ transition [26].

- Quantum Yield Measurement: Use an integrating sphere to determine absolute PLQY.

- Structural Characterization: Perform Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to confirm particle size, morphology, and crystallinity [26].

Protocol 3: Fluorescence-Based Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (Fl-NTA) for Extracellular Vesicle Detection

This protocol highlights the use of QDs for sensitive immunolabelling in Fl-NTA [7].

- Objective: To specifically label and detect extracellular vesicle (EV) subpopulations with high sensitivity and photostability, overcoming limitations of organic dyes.

- Materials & Reagents:

- EV Samples: Isolated from cell culture media (e.g., A549, THP-1 cells).

- Antibodies: Anti-human CD9, CD63.

- Fluorophores: QD625 (functionalized quantum dots) vs. Alexa 488 (organic dye).

- NTA Instrument: Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer with fluorescence laser and long-pass filter.

- Methodology:

- QD Conjugation: Conjugate QD625 to antibodies using a SiteClick coupling kit, which attaches dibenzocyclooctyne (DIBO)-modified QDs to azide-modified antibodies [7].

- EV Immunolabelling: Incubate isolated EVs with QD-conjugated antibodies (anti-CD9, anti-CD63) to form immunocomplexes. Optimize labeling conditions to minimize non-specific binding [7].

- Fl-NTA Measurement:

- Inject the labeled EV sample into the NTA instrument.

- Use a laser to excite the fluorophores and a camera to track the Brownian motion of individual particles.

- Apply a long-pass filter to detect only fluorescence emission, excluding scattered light.

- Data Analysis: The software calculates the size and concentration of fluorescently labeled particles. Compare the performance of QDs and organic dyes based on the number concentration of detected EVs and the lower size limit of detection [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Fluorescence-Based Detection Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Triphenylphosphine (TPP) | Multifunctional ligand for QDs; acts as surface passivant, photoinitiator, and oxidation protector [27]. | Enables high-resolution, ambient-condition photopatterning of RGB QDs for displays with high external quantum efficiency [27]. |

| Morgan Fingerprints | A computational method to encode the structure of a molecule into a numerical bit-string for machine learning [24]. | Used as input features for ML models to predict photophysical properties like Stokes shift from molecular structure alone [24]. |

| Mn²⁺ Dopant Ions | Introduces new mid-gap energy states within a QD's bandgap, enabling large Stokes shift emission via d-d transitions [26]. | Synthesis of heavy-metal-free ZnSe:Mn²⁺/ZnS QDs for luminescent solar concentrators with minimal reabsorption [26]. |

| SiteClick Conjugation Kit | Provides a controlled, site-specific method for conjugating antibodies to quantum dots or other biomolecules [7]. | Creating stable immunoconjugates (e.g., anti-CD63-QD625) for highly specific and photostable detection of extracellular vesicles [7]. |

| Poly(lauryl methacrylate) (PLMA) | A transparent polymer matrix used to host and disperse fluorophores for device fabrication [26]. | Fabricating transparent composite films for luminescent solar concentrators, maintaining high transparency and luminophore performance [26]. |

The comparative analysis of core optical properties reveals a clear, application-dependent landscape for selecting between organic dyes and quantum dots. Organic dyes remain suitable for many conventional applications, particularly with the advent of machine learning models that can predict their properties to guide design [24]. However, quantum dots offer superior performance in metrics critical for advanced detection research: their broad absorption and narrow, tunable emission simplify experimental design for multiplexing; their large, engineerable Stokes shift minimizes signal loss; and their exceptional brightness and photostability enable long-term, sensitive detection of low-abundance targets [19]. The ongoing development of sophisticated QDs, such as heavy-metal-free doped structures [26] and robust surface chemistries for bioconjugation [7], continues to expand their utility, solidifying their role as powerful tools in the scientist's arsenal for diagnostic and therapeutic research.

The evolution of fluorescent nanomaterials has profoundly impacted detection research, offering scientists powerful tools for probing biological and chemical environments. Among these, cadmium selenide quantum dots (CdSe QDs) and carbon-based dyes, including carbon dots (CDs) and carbon quantum dots (CQDs), represent two prominent classes of materials with distinct compositional and structural characteristics. CdSe QDs are semiconductor nanocrystals known for their size-tunable optical properties and high quantum yield [29] [30]. In contrast, carbon dyes are fluorescent nanoparticles primarily composed of carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen, celebrated for their biocompatibility, tunable surface chemistry, and straightforward synthesis from diverse precursors [31] [32] [33]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these materials within detection research, presenting experimental data, methodologies, and practical resources to inform selection for specific applications across biomedical, environmental, and analytical chemistry domains.

Material Composition and Fundamental Properties

The fundamental differences between CdSe QDs and carbon dyes originate from their distinct material compositions and resulting structural properties.

CdSe Quantum Dots feature a crystalline core of cadmium and selenium atoms, typically surrounded by an inorganic shell (e.g., ZnS) and organic ligand coatings [30] [34]. This core-shell structure enhances fluorescence quantum yield and stability. Their most defining characteristic is the quantum confinement effect, where the bandgap energy increases as the particle size decreases, enabling precise tuning of emission wavelengths from approximately 500 nm to 800 nm by varying the core size [34]. They exhibit high fluorescence quantum yields (0.4 to 0.9), broad absorption spectra, and narrow, symmetric emission bands [30].

Carbon Dyes (CDs/CQDs) possess a more varied structure, typically consisting of a carbon-based core with amorphous or nanocrystalline graphitic domains and a surface rich in functional groups such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amine groups [32] [33] [35]. Their photoluminescence stems from a combination of quantum confinement in the sp² carbon domains and surface state emissions [36]. Unlike CdSe QDs, their emission profiles are often broader and can be tuned through precursor selection, doping, and surface functionalization rather than solely by size control [33]. They are noted for excellent water solubility, biocompatibility, and resistance to photobleaching [32].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties and Compositional Comparison

| Property | CdSe QDs | Carbon Dots (CDs) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Composition | Cadmium Selenide (CdSe) | Carbon, primarily sp²/sp³ hybridized |

| Typical Structure | Crystalline core-inorganic shell (e.g., ZnS) | Carbon core with functionalized surface |

| Size Range | 2-10 nm [34] | Typically < 10 nm [33] |

| Quantum Yield Range | 40% - 90% [30] | Up to 83% reported for specific CDCQDs [33] |

| Emission Tunability | Primarily via crystal size (Quantum Confinement) [34] | Via precursor, doping, and surface states [32] [33] |

| Biocompatibility | Lower (Cd toxicity concerns); requires shelling [29] [34] | High; often synthesized from benign precursors [31] [35] |

Detection Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The operational principles of CdSe QDs and carbon dyes in sensing applications diverge significantly, leveraging their unique photophysical interactions with the environment.

CdSe QD-Based Detection

CdSe QDs often function through energy transfer mechanisms or as photothermal converters. In photothermal therapy, brown or deep-colored CdSe QDs efficiently convert laser light (e.g., 671 nm) into heat, enabling tumor ablation [29]. For sensing, they can be paired with pH-sensitive dyes like Phenol Red. In one CO₂ sensor design, CdSe/ZnS QDs act as a stable fluorescent reference, while the pH-sensitive dye changes its absorption in response to CO₂-induced acidity, affecting the overall fluorescence output via an inner filter effect or fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [37].

Carbon Dye-Based Detection

Carbon dyes employ more diverse sensing mechanisms. A primary mechanism is fluorescence quenching via electron or energy transfer upon analyte binding [31] [38]. For instance, CDs can detect metal ions like Fe³⁺ through fluorescence quenching facilitated by interactions with the CD surface [31]. Ratiometric sensing is another powerful approach. Specific CDs exhibit solvatochromic properties, where the intensity ratio of two emission peaks (e.g., red and blue) changes dramatically with microenvironmental polarity [32]. This allows for self-calibrating measurements, as demonstrated by a 30-fold enhancement in the red-to-blue emission ratio when solvent polarity changed, enabling precise mapping of low-polarity environments like lipid droplets in cells [32].

The following diagram illustrates the core detection signaling pathways for both material types.

Comparative Performance Analysis in Detection Applications

Direct comparison of experimental data reveals distinct performance advantages and limitations for each material class across various sensing applications.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison in Detection Applications

| Application & Material | Detection Mechanism | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO₂ Sensing(CdSe/ZnS QDs + Phenol Red) | Fluorescence intensity change & wavelength shift | SensitivityWavelength Shift | 2110.1657 nm/% | [37] |

| Cancer Photothermal Therapy(CdTe(710) QDs) | Photothermal conversion | Tumor growth inhibition | Significant inhibition, eventual tumor disappearance | [29] |

| Polarity Sensing / Lipid Droplet Imaging(Dual-emission CDs) | Ratiometric (Red/Blue emission shift) | Intensity Ratio Enhancement | 30-fold increase (polarity shift: 0.245 to 0.318) | [32] |

| Heavy Metal Sensing(Carbon Dots) | Fluorescence Quenching | Detection of various metal ions | Effective for Fe³⁺, Cu²⁺, etc. | [31] [38] |

| Nucleic Acid Staining(Licorice-derived CDs) | Groove binding & electrostatic interaction | DNA/RNA visualization in gels | Effective replacement for toxic ethidium bromide | [35] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of the experimental groundwork behind the data, this section outlines key methodologies for both material synthesis and sensor fabrication.

Synthesis of CdSe/ZnS QDs for CO₂ Sensing

The following protocol is adapted from the work on optical CO₂ sensors [37].

- Materials: CdSe/ZnS core/shell QDs (commercially available), Phenol Red (pH indicator), poly(isobutyl methacrylate) (polyIBM) polymer matrix, toluene (solvent), anodized aluminum oxide (AAO) substrate, tetraoctylammonium hydroxide (TOAOH).

- Sensor Fabrication Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the CdSe/ZnS QDs, Phenol Red, and polyIBM in toluene to form a homogeneous sensing solution. The polyIBM acts as a gas-permeable matrix that hosts the sensing elements.

- Substrate Preparation: Clean a glass substrate thoroughly, first with soap water for 15 minutes, followed by isopropanol for another 15 minutes. Air-dry the glass at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- AAO Mounting: Place the porous AAO substrate (60 μm thick) onto the prepared glass substrate.

- Coating: Drop-cast 30 μL of the sensing solution uniformly onto the AAO substrate.

- Drying: Dry the coated sensor at 40°C for 15 minutes to evaporate the solvent and form a stable film.

- Measurement Setup: Use a 405 nm LED light source for excitation. Monitor the fluorescence emission peak at 570 nm. Expose the sensor to varying concentrations of CO₂ (0-100%) in a controlled gas chamber and record the corresponding changes in fluorescence intensity and wavelength shift [37].

Synthesis of Polarity-Sensitive Dual-Emitting Carbon Dots (DCDs)

This protocol details the synthesis of DCDs used for ratiometric polarity sensing and lipid droplet imaging [32].

- Materials: Anhydrous citric acid (CA, carbon source), tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (tris buffer, electron donor), polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG400, surface coating agent), formamide (reaction solvent and nitrogen dopant).

- Synthesis Procedure:

- Reaction Mixture: Combine CA, tris buffer, and PEG400 in formamide solvent.

- Solvothermal Reaction: Transfer the mixture to a sealed autoclave and react at a specific temperature (e.g., 160°C) for several hours. The exact parameters (time, temperature) are often optimized by the researcher.

- Purification: After the reaction, allow the autoclave to cool naturally. Purify the resulting DCD solution by centrifugation and dialysis to remove unreacted precursors and byproducts.

- Cell Imaging and Polarity Sensing Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Grow HeLa cells (or other cell lines of interest) in standard culture medium.

- Staining: Incubate the cells with the purified DCD solution at a non-toxic working concentration for a set period.

- Washing & Imaging: Wash the cells with buffer to remove excess DCDs. Mount the cells for live-cell imaging.

- Data Acquisition: Use a confocal microscope with appropriate filter sets. Excite the DCDs and collect emission simultaneously in the blue and red channels.

- Ratiometric Analysis: Calculate the intensity ratio of the red channel to the blue channel (Ired / Iblue) for each pixel. This ratio provides a quantitative, self-referenced map of local polarity, with higher ratios indicating lower polarity regions like lipid droplets [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation requires a curated set of high-quality materials. The following table lists key reagents and their functions for working with CdSe QDs and Carbon Dots in detection research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cadmium Selenide (CdSe) QDs | Core fluorescent nanomaterial; provides tunable emission and high QY. | Often purchased as core-shell CdSe/ZnS; available with various surface functionalizations (e.g., carboxyl, amine) for bioconjugation [30] [37]. |

| Carbon Dots (CDs) | Core fluorescent nanomaterial; provides biocompatibility and tunable surface chemistry. | Can be synthesized in-lab from precursors like citric acid and tris buffer [32], or purchased. |

| Poly(IBM) (poly(isobutyl methacrylate)) | Polymer matrix for gas sensors; provides a permeable host for indicators. | Used in CO₂ sensors to entrap QDs and Phenol Red, facilitating gas diffusion [37]. |

| Anodized Aluminum Oxide (AAO) | Substrate for sensor fabrication; provides high surface area and nanoporosity. | Enhances sensor sensitivity due to its porous structure, maximizing analyte interaction [37]. |

| Phenol Red | pH-sensitive indicator dye for CO₂ detection. | Works in conjunction with CdSe/ZnS QDs in a composite film; CO₂-induced acidosis causes spectral changes [37]. |

| Formamide | Solvent and nitrogen dopant in CD synthesis. | Used in solvothermal synthesis of polarity-sensitive DCDs [32]. |

| Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris Buffer) | Electron-donating precursor in CD synthesis. | Modulates the surface states of CDs, influencing their optical properties [32]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG400) | Surface coating/passivating agent in nanomaterial synthesis. | Improves biocompatibility and water solubility of nanoparticles; used in CD synthesis [32]. |

The choice between CdSe QDs and carbon dyes is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with application requirements. CdSe QDs offer superior brightness, well-defined optical properties, and proven efficacy in photothermal applications and as stable reference fluorophores in sensor designs [29] [37]. However, their inherent cadmium toxicity poses challenges for in vivo applications and environmental disposal [34]. Carbon dyes, particularly CDs, present a compelling alternative with their high biocompatibility, low toxicity, and versatile, eco-friendly synthesis [31] [35]. Their ability to facilitate advanced sensing schemes, such as intrinsically ratiometric polarity detection, provides a significant advantage for quantitative bioimaging and complex environmental analysis [32].

The future of detection research lies in leveraging the strengths of each material and potentially engineering hybrid systems. For instance, the exceptional photostability of CdSe QDs could be harnessed in ex vivo diagnostic devices, while the biosafety of carbon dyes makes them ideal for intracellular sensing and long-term in vivo imaging. As green synthesis methods for CDs advance and surface engineering of both material classes becomes more sophisticated, their efficacy and application scope will continue to expand, solidifying their roles as indispensable tools in the scientist's toolkit.

Synthesis, Functionalization, and Diagnostic Applications in Biomedicine

Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down Synthesis Approaches for Quantum Dots

The unique optical properties of quantum dots (QDs), such as their size-tunable photoluminescence and high photostability, have positioned them as superior alternatives to traditional organic dyes in detection research [18]. A critical factor determining their performance in applications like biosensing and bioimaging is the method used for their synthesis. The two fundamental approaches—bottom-up and top-down—offer distinct pathways for QD fabrication, each with characteristic implications for the resulting nanomaterial's size, morphology, surface chemistry, and ultimately, its efficacy in analytical applications [39] [40]. This guide objectively compares these synthesis methodologies, providing supporting experimental data to inform their selection within a research and development context.

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Top-Down Synthesis Approach

The top-down approach involves the mechanical or chemical breakdown of bulk materials into nanostructures [39]. This method is analogous to sculpting, where a larger piece of material is carved down to the desired nanoscale form.

Key Techniques:

- High-Energy Milling: Uses kinetic energy to grind bulk materials into nanoparticles. While suitable for some metals and oxides, it offers limited control over size, often resulting in broad size distributions (hundreds of nanometers) [41].

- Laser Ablation: Utilizes high-energy laser pulses to vaporize and fragment a target material in a liquid or gas, forming nanoparticles [39].

- Etching: Employs chemical or physical means to remove material from a surface to delineate nanoscale features [40].

Bottom-Up Synthesis Approach

In contrast, the bottom-up approach constructs nanomaterials atom-by-atom or molecule-by-molecule via chemical reactions [39] [40]. This method mimics natural building processes, allowing for precise control at the molecular level.

Key Techniques:

- Precipitation (Wet-Chemical): Precursor solutions rapidly form small nuclei, which are then grown to the desired size. This method allows for excellent control over size, shape, and surface functionalization [41].

- Solvothermal/Hydrothermal Synthesis: Reactions occur in a sealed vessel (autoclave) at high temperature and pressure, using a solvent (organic or water, respectively) to facilitate nanomaterial formation [41] [42].

- Plasma/Flame Pyrolysis: Involves a gas-phase reaction where precursors are decomposed at high temperatures to form nanoparticles. This method is cost-effective for mass production but offers limited customization [41].

- Microwave-Assisted Synthesis: Uses microwave radiation to heat the reaction mixture uniformly and rapidly, reducing synthesis times [42].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow of both synthesis approaches.

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Disadvantages

The choice between synthesis strategies involves balancing control, scalability, cost, and the specific requirements of the intended application.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Synthesis Methods

| Feature | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Breaking down bulk material [39] | Building from atoms/molecules [39] |

| Control over Size & Shape | Limited control, broader size distribution [41] | High precision and control [40] [41] |

| Surface Quality | Often defective surfaces [39] | Can produce high-quality, uniform surfaces [41] |

| Complex Structures | Limited ability for complex structures [41] | Enables alloys, core-shell structures, and complex morphologies [41] |

| Scalability & Cost | Can be cost-effective for mass production of some materials; High-energy milling startup costs can be high [41] | Varies by method; Flame pyrolysis is low-cost, while solvothermal is higher cost [41] |

| Equipment & Complexity | Requires specialized physical equipment (e.g., mills, ablation systems) [39] | Often requires chemical reactors and purification steps [41] [42] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity for certain materials and applications | Superior design precision and customizability [41] |

| Major Limitation | Limited customization and design precision [41] | Requires purification to remove molecular byproducts [42] |

Table 2: Suitability of Quantum Dot Synthesis Methods for Detection Research

| Method | Typical QD Types | Suitability for Detection Research |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | Metal, metal oxide, CDs, core-shell QDs [41] | High. Excellent for creating customized QDs with specific optical properties and surface functionalization for sensing [41]. |

| Solvothermal/Hydrothermal | Carbon Dots (CDs), various QDs [41] [42] | High. Enables synthesis of CDs with tailored fluorescence; requires careful purification [42]. |

| Pyrolysis | CDs, metal oxides [42] [41] | Moderate to Low. Good for large-scale CD production, but limited control over properties and aggregation can be problematic for sensor integration [41]. |

| High-Energy Milling | Ceramics, metals, oxides [41] | Low. Primarily for materials where optical properties are not critical; broad size distribution is unsuitable for precise detection [41]. |

Experimental Data and Performance in Detection Applications

The synthesis method directly impacts QD performance in real-world sensing applications, such as Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based biosensors and environmental monitoring.

Performance in FRET-Based Biosensing

A systematic study comparing QDs and organic dyes in a progesterone biosensor highlights the material-dependent performance. The experimental protocol involved constructing four different biosensor configurations using a transcription factor (TF) and its cognate DNA sequence, labeled with either a CdSe/CdS/ZnS QD donor (emitting at 613 nm) or organic dye donors (Texas Red), and Cy5 as an acceptor [43].

Key Experimental Data:

- QD Donor Configurations: QDs were functionalized with either histidine-tagged TFs or DBCO-grafted polymer for DNA attachment via click chemistry, achieving ~4 TFs or ~18 DNA strands per QD, respectively [43].

- Organic Dye Configurations: Dyes (Texas Red, Cy5) were conjugated to TFs via a C-terminal cysteine or purchased as labeled DNA strands [43].

- Quantum Yield (QY): The QD donor maintained a QY of 25-37%. In contrast, when organic dyes were conjugated to the TF protein, their QY significantly decreased (e.g., Texas Red from 70% to 24%; Cy5 from 23% to 7%) [43].

- Implication for Sensing: The stable, high QY of QDs and their ability to host multiple acceptors make them superior FRET donors, potentially leading to higher FRET efficiency and better signal-to-noise ratios compared to organic dyes, which can suffer from property degradation upon bioconjugation [43].

Application in Environmental and Biomedical Detection

Bottom-up synthesized QDs, particularly Carbon Dots (CDs), are widely used in fluorescence sensors for environmental and biomedical monitoring [31] [18]. Their performance is tied to the synthesis method.

Sensing Mechanisms and Experimental Workflow: CDs act as nanosensors through mechanisms like fluorescence quenching upon interaction with target analytes, such as iron ions in corrosive environments [31] or pesticides in water [18]. A generalized experimental workflow is below.

Key Experimental Insight: A critical experimental step for bottom-up CDs is purification. Studies emphasize that the optical properties of as-synthesized CDs can be confounded by small molecular fluorophore byproducts (e.g., IPCA from citric acid/ethylenediamine reactions). Reliable sensor performance requires rigorous purification via dialysis, gel electrophoresis, or size-exclusion chromatography to isolate the genuine CD fraction [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Quantum Dot Synthesis and Application

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Citric Acid & Amines | Common precursors for bottom-up synthesis of Carbon Dots (CDs) [42]. | Hydrothermal synthesis of nitrogen-doped CDs with tunable fluorescence [42]. |

| Metal Salts | Precursors for semiconductor QD cores (e.g., CdSe, ZnS) [18]. | Precipitation synthesis of core/shell CdSe/CdS/ZnS QDs for FRET biosensing [43]. |

| Surface Capping Ligands | Control QD growth, prevent aggregation, and provide functional groups for bioconjugation [41]. | Use of polymers with imidazole and DBCO for grafting DNA strands onto QDs [43]. |

| Solvents | Medium for chemical reactions (water, organic solvents). | Water for hydrothermal synthesis; organic solvents for solvothermal synthesis [41] [42]. |

| Purification Materials | Separate pure QDs from reaction byproducts and unreacted precursors. | Dialysis membranes, gel electrophoresis, and size-exclusion chromatography columns [42]. |

| Conjugation Reagents | Link QDs to biomolecules (antibodies, DNA, proteins). | SiteClick antibody labeling kit for conjugating QD625 to anti-CD9 and anti-CD63 antibodies [7]. |

Chemical Synthesis and Modification Routes for Organic Dyes

In the evolving landscape of detection research, the choice of fluorescent probe is paramount. For decades, organic dyes have been the cornerstone of fluorescence-based applications, from biosensing and bioimaging to diagnostic assays. Their well-established synthesis and modification routes offer a high degree of customization for specific research needs. However, the emergence of quantum dots (QDs)—semiconductor nanocrystals with unique optical properties—has introduced a powerful alternative, prompting a critical re-evaluation of probe efficacy. This guide provides an objective comparison of organic dyes and quantum dots, focusing on their chemical synthesis, functionalization, and ultimate performance in detection research. By framing this analysis within the broader thesis of efficacy, we aim to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the data necessary to select the optimal probe for their specific applications, particularly in demanding environments requiring high sensitivity and photostability.

Synthesis and Modification of Organic Dyes

The synthesis of organic dyes is a mature field rooted in traditional organic chemistry, offering a diverse palette of structures through rational design. A common and highly tunable design for metal-free organic dyes, especially in applications like dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), is the donor-π-conjugated bridge-acceptor (D-π-A) structure. This push-pull system facilitates intramolecular charge transfer (ICT), which is crucial for light absorption and fluorescence emission [44].

Chemical modification allows for precise tuning of a dye's properties. For instance, introducing an auxiliary acceptor unit, transforming the structure into a D-A-π-A system, can effectively red-shift the absorption spectrum and reduce the optical band gap. A comparative study on phenothiazine-based dyes PTZ-3 (D-π-A) and PTZ-5 (D-A-π-A) demonstrated that the incorporation of a benzothiadiazole (BTD) auxiliary acceptor red-shifted the maximum absorption wavelength from 449 nm to 506 nm [44]. However, this modification also led to a lower molar extinction coefficient (from 62.3 × 10³ M⁻¹cm⁻¹ to 38.0 × 10³ M⁻¹cm⁻¹) and a decreased dihedral angle, which can reduce the efficiency of ICT [44]. This illustrates the trade-offs inherent in dye molecular engineering.

Conjugation of organic dyes to biomolecules, such as antibodies for immunolabelling, is typically achieved through functional groups like maleimide, which reacts with thiol groups in proteins. For example, labeling a transcription factor (TF) with Texas Red (TR) or Cy5 via a C-terminal cysteine residue achieved a high conjugation efficiency of approximately 90% [43].

Table 1: Impact of Molecular Structure on Organic Dye Properties

| Dye Structure | Example Dye | Maximum Absorption Wavelength (nm) | Molar Extinction Coefficient (×10³ M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Band Gap (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-π-A | PTZ-3 | 449 | 62.3 | 2.5 |

| D-A-π-A | PTZ-5 | 506 | 38.0 | 2.28 |

Synthesis and Functionalization of Quantum Dots

In contrast to organic dyes, quantum dots are inorganic nanocrystals whose synthesis leverages colloidal chemistry in high-temperature organic solvents. The most common QDs are based on cadmium selenide (CdSe), often grown with a shell of a wider bandgap semiconductor like zinc sulfide (ZnS) to form a core-shell structure (e.g., CdSe/CdS/ZnS) that significantly improves quantum yield and photostability [43] [6]. The defining feature of QD synthesis is the quantum confinement effect, which allows for precise tuning of the emitted light's color simply by varying the crystal size. For instance, CdSe QDs can be engineered to emit from blue (∼450 nm) to red (∼650 nm) by increasing their size from 2 nm to 6 nm [6] [9].

A significant focus in QD development is the move toward cadmium-free compositions, such as indium phosphide (InP) and perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), to address environmental and regulatory concerns [6] [9]. Furthermore, carbon-based nanomaterials like carbon dots (CDs) and graphene quantum dots (GQDs) have emerged as biocompatible alternatives with facile synthesis and tunable surface chemistry [31].

The functionalization of QDs for biological applications is a critical step. Two common strategies are:

- His-Tag Conjugation: A histidine-tagged protein (e.g., TF-his6) can self-assemble onto the QD surface via metal-affinity coordination, typically at a controlled molar ratio (e.g., 4:1 protein-to-QD) to ensure functionality and avoid non-functionalized QDs [43].

- Polymer Coating and Click Chemistry: QDs can be encapsulated with a zwitterionic copolymer bearing functional groups like dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO). Copper-free click chemistry can then be used to graft azide-modified DNA strands onto the QD surface with high efficiency (>90%), achieving a high density of DNA (e.g., 18 strands per QD) [43].

Table 2: Common Quantum Dot Types and Their Properties

| QD Type | Core Material | Size Range | Emission Range | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium-Based | CdSe, CdS | 2-6 nm | ~450-650 nm | High quantum yield (50-90%), tunable, but contains toxic cadmium [6] [9] |

| Cadmium-Free | InP | Up to 8 nm | Tunable | Safer alternative, developed to meet environmental regulations [9] |

| Perovskite (PQDs) | CsPbX₃ | - | Tunable | High color purity, but stability can be a challenge [9] |

| Carbon Dots (CDs) | Carbon | - | Tunable | Biocompatible, suited for corrosion sensing and biofouling monitoring [31] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Direct, head-to-head experimental comparisons provide the most objective data for evaluating probe efficacy. A seminal 2022 study systematically compared organic fluorophores (Cy5, Texas Red) and inorganic nanoparticles (CdSe/CdS/ZnS QDs) in a FRET-based biosensor for progesterone [43]. The performance metrics from this study are highly revealing.

The core-shell-shell CdSe/CdS/ZnS QDs used exhibited a high quantum yield (25-37%) [43]. In contrast, when organic dyes were conjugated to proteins, their quantum yields significantly decreased. Texas Red dropped from ~70% in free solution to 24% when conjugated to a protein, and Cy5 experienced an even more dramatic drop from 23% to 7%, along with a hypsochromically shifted emission, suggesting potential aggregation or interaction with the protein environment [43]. This highlights a key vulnerability of organic dyes that QDs, due to their inorganic core, largely avoid.

This stability advantage translates directly into performance. In a comparative study for immunolabelling extracellular vesicles (EVs), QD-conjugated antibodies outperformed those conjugated with the organic dye Alexa 488. The QDs' superior brightness and photostability enabled more sensitive detection and allowed for the identification of smaller EV populations, providing a more accurate characterisation of EV heterogeneity [7]. Furthermore, QD-infused nanocomposites have demonstrated capability for ultra-sensitive detection of biomarkers at femtomolar (10⁻¹⁵ M) concentrations in complex biological environments, a level of sensitivity that is challenging to achieve with traditional organic dyes [6].

Table 3: Experimental Performance Comparison in FRET Biosensor [43]

| Fluorophore Type | Example | Quantum Yield (Conjugated) | Photostability | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Dye | Texas Red, Cy5 | Low to Moderate (7%-24%) | Prone to photobleaching | Small size, well-established chemistry |

| Quantum Dot | CdSe/CdS/ZnS | High (25%-37%) | Exceptional; resistant to photobleaching | High brightness, tunability, multiplexing capability |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for comparison, this section outlines key experimental methodologies cited in the performance data.

Protocol 1: Conjugation of Organic Dyes to Proteins via C-Terminal Cysteine

This protocol is adapted from the FRET biosensor study [43].

- Protein Engineering: Design the target protein sequence to include a single, accessible C-terminal cysteine residue.

- Dye Preparation: Prepare a solution of the maleimide-functionalized organic dye (e.g., Texas Red or Cy5 maleimide).

- Conjugation Reaction: Mix the purified protein with the dye in a suitable buffer (e.g., HEPES, pH ~7.0) at a predetermined molar ratio. Allow the reaction to proceed in the dark for several hours.

- Purification: Remove unreacted dye from the labeled protein using purification techniques such as size-exclusion chromatography or dialysis.

- Validation: Confirm conjugation and estimate labeling efficiency (typically >90%) using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry and absorption measurements [43].

Protocol 2: Functionalization of QDs with DNA via Click Chemistry

This protocol details the grafting of DNA strands onto QDs, as performed in the comparative biosensor study [43].

- QD Preparation: Synthesize or acquire core-shell CdSe/CdS/ZnS QDs. Encapsulate them with a custom zwitterionic polymer bearing 40% imidazole groups (for QD anchoring) and 10% dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) groups.

- DNA Modification: Acquire DNA oligonucleotides with a 5'-azide modification. Hybridize them with their complement strand if a double-stranded sequence is required.

- Click Conjugation: Mix the DBCO-functionalized QDs with the azide-modified DNA in buffer. The copper-free click reaction between DBCO and azide will proceed spontaneously.

- Purification and Quantification: Purify the QD-DNA conjugates to remove excess DNA. Determine the average number of DNA strands per QD (e.g., ~18 strands) using spectroscopic methods [43].

Protocol 3: Quantitative Determination of Labeling Efficiency

Accurate quantification of labeling efficiency is critical for quantitative biosensing. The following ratiometric method overcomes the limitations of traditional approaches by operating in the same conditions as the target experiment [45].

- Sample Preparation: Use two identical samples of the target (e.g., cells expressing the labelable receptor).

- Sequential Labeling:

- Sample A: Perform the first labeling reaction with fluorophore A (efficiency eA), then a second labeling reaction with fluorophore B (efficiency eB).

- Sample B: Perform the first labeling reaction with fluorophore B, then the second with fluorophore A.

- Measurement: Measure the ratio (r and r') of the number of molecules labeled in the first reaction to the number labeled in the second reaction for each sample. The number of molecules can be derived from fluorescence intensity measurements calibrated by single-molecule fluorescence.

- Calculation: Solve the system of equations to determine the absolute labeling efficiencies e_A and e_B for the two probes under the specific experimental conditions [45].

Diagram 1: Ratiometric labeling efficiency workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key materials and their functions for working with organic dyes and quantum dots in detection research, based on the cited literature.

Table 4: Essential Reagent Solutions for Fluorescent Probe Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Maleimide-functionalized Dyes | Covalent conjugation to thiol groups (-SH) in cysteine residues of proteins. | Labeling transcription factors with Texas Red or Cy5 [43]. |

| DBCO/Azide Click Chemistry Kits | For copper-free, bio-orthogonal conjugation of biomolecules (e.g., DNA, antibodies) to functionalized nanoparticles. | Grafting azide-DNA to DBCO-polymer coated QDs [43]. |

| SiteClick Antibody Labeling Kit | A specific kit for site-specific conjugation of QDs to antibodies, minimizing loss of activity. | Conjugating QD625 to anti-CD9 and anti-CD63 antibodies for EV immunolabelling [7]. |