Rapid Prototyping Revolution: A Comprehensive Guide to 3D Printing Microfluidic Devices for Biomedical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to leveraging 3D printing for rapid microfluidic device prototyping.

Rapid Prototyping Revolution: A Comprehensive Guide to 3D Printing Microfluidic Devices for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to leveraging 3D printing for rapid microfluidic device prototyping. We explore foundational principles, compare vat polymerization (SLA/DLP), material jetting, and fused deposition modeling (FDM) methods, detail practical workflows from design to post-processing, address common troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and validate performance against traditional fabrication techniques. The content synthesizes current methodologies to empower labs to accelerate their microfluidics research and development cycles.

From CAD to Chip: Understanding 3D Printing's Role in Modern Microfluidics Prototyping

Application Notes: Accelerating Microfluidic Development with 3D-Printed Prototypes

The integration of 3D printing into microfluidics research enables an iterative design-test-refine cycle, compressing development timelines from months to days. This acceleration is critical for applications in point-of-care diagnostics, organ-on-a-chip systems, and high-throughput drug screening. The direct translation of CAD models to functional devices allows for the rapid exploration of complex geometries—such as serpentine mixers, droplet generators, and concentration gradient networks—that are costly or impossible with traditional soft lithography.

Table 1: Comparison of Prototyping Methods for Microfluidics

| Method | Typical Turnaround Time | Minimum Feature Size (µm) | Approx. Cost per Prototype | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS Soft Lithography | 1-3 days | ~10 | $50-$200 | Master mold fabrication bottleneck |

| Stereo-lithography (SLA) 3D Printing | 1-4 hours | ~25 | $5-$20 | Biocompatibility post-processing |

| Inkjet 3D Printing | 2-8 hours | ~50 | $10-$40 | Material property limitations |

| PolyJet 3D Printing | 3-10 hours | ~16 | $30-$100 | Support material removal |

| CNC Machining (PMMA) | 1-2 days | ~100 | $100-$500 | Limited to 2.5D geometries |

| Injection Molding | 4-8 weeks | ~10 | $1000+ (initial tooling) | Not suitable for prototyping |

Note: Data compiled from recent literature and vendor specifications (2023-2024). Turnaround time includes post-processing.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rapid Fabrication of a Droplet Generator via SLA 3D Printing

This protocol details the fabrication of a water-in-oil droplet generator for single-cell analysis applications.

Materials & Equipment:

- SLA 3D Printer (e.g., Formlabs Form 3+)

- Biocompatible Photopolymer Resin (e.g., Formlabs BioMed Clear)

- Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA, >99%)

- UV Curing Chamber

- Syringes (1 mL) and PTFE tubing (0.02” ID)

- Syringe pumps

- Surfactant solution (e.g., 2% Span 80 in mineral oil)

- Aqueous sample solution

Procedure:

- Design: Create a droplet generator design (flow-focusing geometry) in CAD software. Channel dimensions: 150 µm (width) x 150 µm (height). Include 1/16” barbed outlet/inlet ports.

- Print Preparation: Orient the model at a 45° angle to minimize step artifacts. Generate supports automatically.

- Printing: Print using 25 µm layer thickness settings. Estimated print time: 2.5 hours.

- Post-Processing: a. Rinse the printed part in IPA bath for 10 minutes with gentle agitation. b. Transfer to a second clean IPA bath for 5 minutes. c. Air dry, then remove support structures. d. Post-cure in a UV oven at 60°C for 15 minutes per side.

- Bonding: Apply a thin layer of uncured resin to the device's mating surface. Place a clean PMMA cover plate on top. Cure under UV light (365 nm) for 5 minutes to seal.

- Fluidic Connection: Press-fit PTFE tubing into barbed inlets.

- Operation: Load the oil phase (with surfactant) and aqueous phase into separate syringes. Connect to device. Set syringe pumps to specific flow rates (e.g., Oil: 500 µL/hr, Aqueous: 100 µL/hr). Collect droplets from outlet.

Validation: Monitor droplet size and generation frequency using high-speed microscopy. Expected output: monodisperse droplets of ~80 µm diameter.

Protocol 2: Functional Testing of a 3D-Printed Gradient Generator for Cell Chemotaxis Studies

This protocol validates the performance of a 3D-printed tree-like concentration gradient generator.

Procedure:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a 3-inlet (1 for buffer, 2 for dye/solute), 7-outlet gradient generator using PolyJet printing (e.g., Stratasys J735) with VeroClear material. Post-process per manufacturer instructions.

- Surface Treatment: To prevent non-specific adsorption, perfuse the device with 1% Pluronic F-127 solution for 1 hour, then rinse with PBS.

- Gradient Calibration: a. Connect syringe pumps to inlets: Inlet 1 (PBS buffer), Inlet 2 (0.1 mg/mL fluorescein solution). b. Set equal flow rates (e.g., 100 µL/hr) for all inlets. c. Run for 10 minutes to establish steady-state flow. d. Collect effluent from each outlet and measure fluorescence intensity with a plate reader. e. Generate a standard curve to correlate intensity with concentration.

- Data Analysis: Plot concentration per outlet. A linear gradient across outlets 1-7 is expected. Calculate coefficient of variation (CV) between repeated runs (<5% is acceptable).

Key Diagrams

Title: Rapid Prototyping Iterative Cycle for Microfluidics

Title: Cell Chemotaxis Assay in a 3D-Printed Microfluidic Device

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Rapid Microfluidic Prototyping Experiments

| Item | Function | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Photopolymer Resin | Primary material for SLA printing; must be non-cytotoxic for cell-based assays. | Formlabs BioMed Clear, Dental SG Resin |

| Support Material (for PolyJet) | Water-soluble gel that supports complex overhangs during printing. | Stratasys SUP706, SUP707 |

| Pluronic F-127 or F-68 | Surface-active agent; used to passivate channels and prevent cell/protein adhesion. | Sigma-Aldrich P2443 |

| PDMS (Sylgard 184) | Often used for comparison or hybrid devices; elastomeric properties. | Dow Sylgard 184 Kit |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Fluorescein) | For visualizing flow patterns, validating gradient generation, and quantifying mixing. | ThermoFisher Scientific F6377 |

| Cell Culture Medium (Serum-Free) | For biological assays; serum-free reduces bubble formation in microchannels. | Gibco FluoroBrite DMEM |

| Precision Syringe Pumps | To provide stable, pulse-free low flow rates (µL/hr to mL/hr) for device operation. | Harvard Apparatus PHD ULTRA, neMESYS |

| Optical Adhesive or Uncured Resin | Used as an adhesive layer for bonding 3D-printed parts to glass or PMMA covers. | Norland Optical Adhesive 81, Original Resin (Formlabs) |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (High Purity) | Critical for washing uncured resin from printed parts in post-processing. | >99% IPA, ACS grade |

| UV Curing Lamp/Oven | For final curing of printed resin to achieve maximum biocompatibility and stability. | Formlabs Form Cure, Any 405nm UV Lamp |

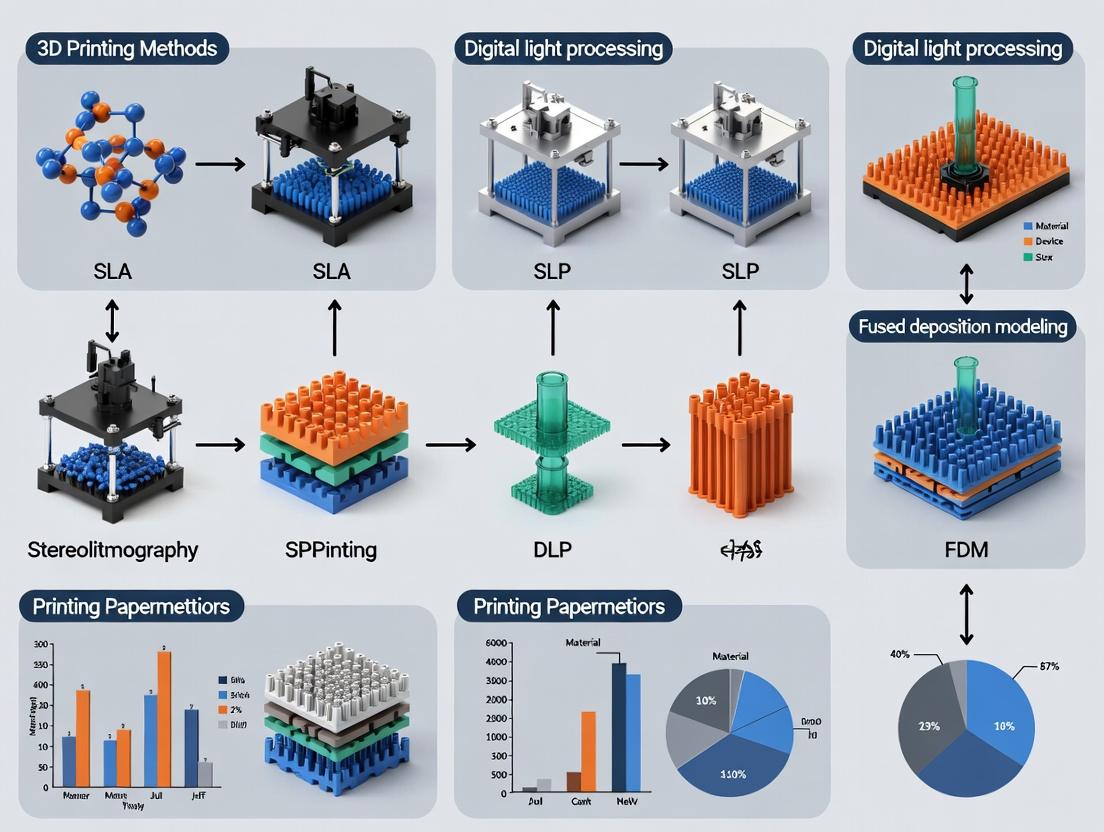

Within the broader research on 3D printing for rapid microfluidic device prototyping, the selection of the core printing technology dictates the functional capabilities, resolution, and application suitability of the final device. This application note details the three predominant technologies—Stereolithography (SLA)/Digital Light Processing (DLP), PolyJet, and Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM)—providing comparative data, experimental protocols for device fabrication, and essential research toolkits to guide researchers and development professionals in microfluidics and drug development.

Technology Comparison and Quantitative Data

Table 1: Core 3D Printing Technology Comparison for Microfluidics

| Parameter | SLA / DLP | PolyJet | FDM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical XY Resolution | 25 - 150 µm | 16 - 42 µm | 100 - 400 µm |

| Typical Layer Height | 10 - 100 µm | 16 - 30 µm | 50 - 300 µm |

| Minimum Feature Size | ~50 - 150 µm | ~20 - 100 µm | ~200 - 500 µm |

| Surface Finish | Smooth | Very Smooth | Layered (Visible Raster Lines) |

| Biocompatible Materials | Limited (e.g., Class I resins) | Several (e.g., MED610) | Common (e.g., PLA, ABS, PP) |

| Multi-Material Capability | No (typically) | Yes (Simultaneous) | Yes (Sequential, with tool changes) |

| Optical Clarity | Good to High | High | Low (Opaque, translucent possible) |

| Typical Build Speed | Moderate to Fast | Moderate | Slow to Moderate |

| Post-Processing Requirement | Mandatory (IPA wash, post-cure) | Support removal (water jet) | Minimal (support removal) |

| Relative Cost (Printer & Material) | Medium | High | Low |

Table 2: Application Suitability for Microfluidic Functions

| Application Goal | Recommended Technology | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Mixers & Droplet Generators | SLA/DLP, PolyJet | Superior resolution for sub-100µm features. |

| Cell Culture & Organ-on-a-Chip | PolyJet (MED610), SLA (Biocompatible resins) | Certified biocompatibility and optical clarity for imaging. |

| Rapid, Low-Cost Prototyping of Macroscopic Fluidic Networks | FDM | Low barrier to entry, fast design iteration for channel >300µm. |

| Integrated Valves/Pumps with Flexible Components | PolyJet | Ability to print rigid and elastomeric materials simultaneously. |

| Optical Detection Flow Cells | SLA/DLP, PolyJet | High clarity and smooth surfaces minimize light scattering. |

Experimental Protocols for Device Fabrication

Protocol 1: Fabricating a Microfluidic Mixer via DLP Printing Objective: To create a herringbone micromixer for rapid fluid blending.

- Design: Using CAD software (e.g., SolidWorks, Fusion 360), design a straight channel (width: 500 µm, height: 250 µm) with integrated staggered herringbone ridges (height: 100 µm) on the channel ceiling. Export as an STL file.

- Preparation: Import the STL into the printer slicer (e.g., ChiTuBox for DLP). Orient the device at a 45-degree angle to minimize layer stepping on critical features. Add support structures automatically. Slice with a layer height of 25 µm.

- Printing: Use a commercially available biocompatible, clear photopolymer resin (e.g., Formlabs Dental SG or equivalent). Initiate the print. The DLP projector will cure each layer based on the sliced image.

- Post-Processing: Upon completion, transfer the print to an isopropyl alcohol (IPA) bath. Agitate for 5 minutes to remove uncured resin. Remove from IPA and gently air dry. Place the device in a UV post-curing chamber (365 nm wavelength) for 20-30 minutes to ensure complete polymerization and optimal mechanical properties.

- Bonding: For enclosed channels, bond the printed part to a flat substrate. Oxygen plasma treat both the device (open face) and a PDMS slab or glass slide for 60 seconds. Bring surfaces into contact immediately to form an irreversible seal.

Protocol 2: Creating a Multi-Material Organ-on-a-Chip Model via PolyJet Objective: To prototype a dual-channel chip with integrated porous membrane.

- Design: Model two overlapping microfluidic channels (1 mm x 1 mm) separated by a thin (100 µm thick) planar membrane. Design the chip body as a single part with the membrane region assigned as a separate body in the CAD assembly.

- Material Assignment: In the PolyJet print preparation software (e.g., GrabCAD Print), assign the main chip body material as a rigid, clear photopolymer (e.g., VeroClear). Assign the membrane region to a digital material simulating a porous, flexible structure (e.g., a blend of Agilus30 and Vero, or use the dedicated "Digital ABS" for rigidity with slight flex).

- Support & Print: The software will automatically generate gel-like support material. Print the job. The printer will jet and UV-cure both model materials simultaneously layer-by-layer.

- Support Removal: After printing, use a high-pressure water jet station to meticulously remove the support material from the delicate channels and membrane.

Protocol 3: Rapid Iteration of a Fluidic Connector Manifold via FDM Objective: To produce a macro-to-micro interface for tubing connections.

- Design: Create a manifold block with multiple inlet/outlet ports (diameter ≥ 1 mm) leading to a common channel. Include features for standard luer lock or barbed fittings.

- Slicing: Import STL into FDM slicer (e.g., Ultimaker Cura, PrusaSlicer). Select a biocompatible filament like PLA or PP. Use a nozzle diameter of 0.25 mm for finer detail. Set layer height to 0.1 mm for better seal surface. Enable "ironing" top surface setting for improved smoothness. Generate tree-style supports for easy removal.

- Printing: Level the print bed. Begin print. Monitor first layer adhesion.

- Post-Processing: Remove support structures manually. Smooth sealing surfaces with fine-grit sandpaper if necessary. Clean channels with compressed air.

Diagrams and Workflows

Title: SLA/DLP Device Fabrication Workflow

Title: Technology Selection Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 3D-Printed Microfluidics Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Photopolymer Resin | For creating devices for cell-contact applications (e.g., organ-on-chip). | Formlabs BioMed Clear, Stratasys MED610. Must be ISO 10993 certified. |

| High-Resolution Clear Resin | For general prototyping requiring optical access and fine features. | Anycubic Clear, Phrozen Aqua-Grey 8K. |

| Dissolvable or Breakaway Support Material | Enables printing of complex, enclosed internal geometries. | PolyJet SUP706 (water jet), SLA Breakaway Support (manual remove). |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Used as a bonding substrate or for creating hybrid devices due to its gas permeability. | Sylgard 184. Often bonded to printed parts. |

| Oxygen Plasma System | Activates surfaces of printed polymers and PDMS/glass for irreversible bonding. | Harrick Plasma Cleaner. Critical for creating sealed devices. |

| Biocompatible FDM Filament | For prototyping fluidic manifolds, holders, or large-scale systems. | PLA (generally safe), Polypropylene (PP, chemical resistant). |

| IPA (≥99% purity) | Mandatory for washing uncured resin from SLA/DLP prints. | Used in post-processing wash stations. |

| UV Post-Curing Chamber | Ensures complete resin polymerization, improving mechanical strength & biocompatibility. | Formlabs Form Cure, or custom-built with 405nm LEDs. |

| Fluidic Connectors & Tubing | Interfaces between macro-world equipment and microfluidic chips. | Luer locks, barbed fittings (e.g., 10-32 thread), PTFE tubing. |

This Application Note is a critical subsection of a broader thesis on 3D printing methods for rapid microfluidic device prototyping for biomedical research. The selection of a biocompatible material is the foundational step determining the success of subsequent cell culture, organ-on-a-chip, or drug screening experiments. This guide categorizes and evaluates mainstream 3D-printable biocompatible materials, providing direct protocols for their implementation in microfluidic research workflows.

Material Categories & Quantitative Comparison

The following tables summarize key properties of commercially available, 3D-printable biocompatible materials relevant to microfluidics. Data is compiled from manufacturer datasheets and recent literature (2023-2024).

Table 1: Biocompatible Vat Polymerization Resins (SLA/DLP)

| Material (Example Trade Name) | Biocompliance Standard (Tested) | Typical Elastic Modulus | Key Advantages for Microfluidics | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methacrylate-based (Formlabs Biomedical Resin) | ISO 10993-5, -10 | 1.5 - 2.0 GPa | High resolution (~50 µm), optical clarity, rigid. | May require extensive post-curing/leaching; can be brittle. |

| Methacrylate-based (Stratasys MED610) | ISO 10993-1 | 2.6 - 2.9 GPa | Biocompatible, long-term implantable (≤30 days). | Requires specialized PolyJet printers; support removal critical. |

| Ceramic-filled (3D Systems Biomaterial) | ISO 10993-5 | 4.0+ GPa | High temperature resistance, sterilizable. | Opaque, high abrasiveness requires hardened tools. |

Table 2: Biocompatible Thermoplastics for FDM/FFF

| Material | Biocompliance | Print Temp (°C) | Glass Transition Tg (°C) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) | 190-220 | 55-60 | Low cost, easy to print, biodegradable. | Hydrolytic degradation, moderate chemical resistance. |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol (PETG) | USP Class VI | 230-250 | 80 | Chemical resistant, transparent, low shrinkage. | Can be challenging to surface functionalize. |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | ISO 10993 | 280-310 | 147 | High strength, heat & chemical resistance, autoclavable. | High printing temp, prone to moisture absorption. |

Table 3: Biocompatible Elastomers for Inkjet, SLA, or Direct Printing

| Material (Type) | Biocompliance | Shore Hardness | Key Advantages for Microfluidics | Primary Printing Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicone (PDMS) Mimics (e.g., Silicone-based Resins) | ISO 10993-5 | 30A - 80A | Elastic, gas-permeable, tunable modulus. | VAT Photopolymerization |

| Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) | USP Class VI | 95A - 74D | Flexible, durable, FDM-printable. | FDM/FFF |

| Hydrogels (GelMA, PEGDA) | Cell-laden compatible | N/A | Support cell growth/embedding, mimic ECM. | Direct Ink Writing (DIW), SLA |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Post-Processing & Validation for Resin-Based Microfluidic Devices

Objective: To render a 3D-printed resin device biocompatible for cell culture.

- Post-Print Wash: Immerse the printed part in ≥99% isopropanol (IPA) for 10 minutes in an ultrasonic bath. Repeat with fresh IPA.

- Secondary Cure & Leaching: Cure under 405 nm UV light (20 mW/cm²) for 30 min per side. Submerge in 70% ethanol and incubate at 60°C on an orbital shaker (50 rpm) for 4 hours.

- Extensive Leaching: Rinse with sterile deionized water. Submerge in sterile PBS (pH 7.4) and incubate at 37°C for 7 days, changing PBS daily.

- Biocompatibility Validation (Direct Contact Test):

- Seed mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293) at 50,000 cells/cm² in a well containing the leached device.

- Incubate for 48 hours (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Assess viability via Calcein-AM/EthD-1 live/dead staining and compare to a tissue culture plastic control (≥80% viability target).

Protocol 3.2: Surface Activation of FDM-Printed Thermoplastics for Bonding

Objective: To create a permanent, leak-tight seal for multilayer thermoplastic microfluidics.

- Surface Preparation: Smooth the bonding surface of the FDM-printed part (e.g., PC, PETG) via light sanding (600-grit) and sonicate in IPA for 5 min.

- Chemical Activation (for PC or PS):

- Prepare a 5% (v/v) solution of 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate in ethanol.

- Immerse the part for 20 minutes, rinse with ethanol, and air dry.

- Thermal Bonding:

- Align the activated part with a flat substrate (e.g., PMMA sheet).

- Place in a programmable hot press with a soft silicone cushion.

- Apply 0.5 MPa pressure at 5°C above the material's Tg for 10 minutes.

- Cool under pressure to

Visualized Workflows & Relationships

Title: Material Selection Decision Workflow for Biocompatible Microfluidics

Title: Post-Processing Protocol for Resin Biocompatibility

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Biocompatible 3D Printing | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Isopropanol (≥99%) | Removes uncured resin residue from printed parts. Essential for preventing cytotoxicity. | Use in a well-ventilated area or fume hood. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), Sterile | For leaching residual monomers and photoinitiators from printed polymers. | Change solution daily during long-term leaching. |

| Calcein-AM / Ethidium Homodimer-1 Kit | Standard live/dead fluorescent assay to validate material cytocompatibility post-processing. | Incubate with cells for 20-45 min before imaging. |

| 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate | Silane coupling agent for surface activation of thermoplastics to enable bonding. | Handle under inert atmosphere; hydrolyzes in air. |

| Sterile Cell Culture Media | For final rinsing and conditioning of devices prior to cell seeding. | Confirms device does not alter media pH/osmolarity. |

| Programmable Hot Press | For thermal fusion bonding of thermoplastic microfluidic layers. | Enables precise control of temperature, pressure, and time. |

Within research on 3D printing for rapid microfluidic device prototyping, Design for Additive Manufacturing (DfAM) is critical. This document outlines key principles and practical protocols for designing and fabricating microfluidic channels using common additive manufacturing technologies, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to accelerate device iteration and functional testing.

Key DfAM Principles & Quantitative Guidelines

Successful printing of microfluidic channels requires adherence to specific design rules tailored to each printing technology. The following table summarizes critical quantitative parameters.

Table 1: DfAM Parameters for Microfluidic Channels by Printing Technology

| Principle / Parameter | Stereolithography (SLA) | Digital Light Processing (DLP) | PolyJet / Material Jetting | Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Channel Width | 100 - 150 µm | 50 - 100 µm | 200 - 300 µm | 300 - 500 µm | Dependent on optical spot size or nozzle diameter. |

| Minimum Feature Size | 50 - 100 µm | 25 - 50 µm | 100 - 150 µm | 150 - 200 µm | Includes pillars, valves, and mixing elements. |

| Aspect Ratio (H:W) Limit | 10:1 | 8:1 | 5:1 | 3:1 | For unsupported vertical walls. |

| Channel Roof Sag Limit | 10:1 (Span:Height) | 8:1 (Span:Height) | 6:1 (Span:Height) | 4:1 (Span:Height) | Maximum unsupported roof span to avoid collapse. |

| Optimal Orientation | 45° from build plate | Vertical (Z-axis) | As designed, multi-material support | Horizontal (XY-plane) | Minimizes stair-step, supports, and printing time. |

| Surface Roughness (Ra) | 0.2 - 1.0 µm | 0.5 - 1.5 µm | 1.0 - 3.0 µm | 5.0 - 20 µm | Critical for optical clarity and flow resistance. |

| Post-Processing Required | IPA Wash, UV Cure | IPA Wash, UV Cure | Support Removal, Water Jet | Support Removal, Solvent Smoothing | Essential for clearing uncured resin or support material from channels. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Vat Polymerization (SLA/DLP) Device Fabrication & Post-Processing

This protocol details the creation of sealed microfluidic devices using vat polymerization, a common high-resolution method.

Materials:

- Clear, biocompatible photopolymer resin (e.g., Formlabs Dental SG, PR48).

- Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA), >99% purity.

- Compressed air or nitrogen gun.

- Secondary UV curing chamber.

- Appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE): nitrile gloves, safety glasses.

Methodology:

- Design & Orientation: Design the microfluidic device with channel dimensions respecting Table 1 limits. Include inlet/outlet ports. Orient the device at a 10-20° angle on the build platform to reduce suction forces and improve channel definition.

- Support Generation: Use the printer's software to generate lightweight, touch-point supports for overhanging channel roofs. Manual editing is often required to ensure supports do not intrude into critical channel areas.

- Printing: Initiate the print using manufacturer-recommended layer thickness (typically 25-100 µm for microfluidics).

- Primary Wash: Immediately after printing, submerge the part in an IPA bath for 5-10 minutes with gentle agitation to remove excess surface resin.

- Channel Clearing: Using a syringe filled with fresh IPA, forcefully flush the channels from the inlet ports to evacuate any trapped uncured resin. Repeat 3-5 times.

- Secondary Wash & Dry: Place the device in a second, clean IPA bath for 2 minutes. Remove and dry thoroughly with compressed air.

- Final Cure: Post-cure the device in a UV chamber for 30-60 minutes per side, ensuring complete polymerization of all internal surfaces.

- Sealing: Bond the cured device to a flat substrate (e.g., glass slide, PMMA) using a compatible UV-curable adhesive or a plasma bonding protocol.

Protocol 2: FDM Nozzle Temperature & Flow Calibration for Channel Integrity

For FDM printing of microfluidic masters or devices, precise calibration is needed to prevent voids or sagging roofs.

Materials:

- Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) or Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) filament, 1.75 mm diameter.

- FDM 3D printer with a 0.25 mm or 0.4 mm nozzle.

Methodology:

- Design Test Coupon: Create a test block containing a series of straight channels (widths: 400, 500, 600 µm; roof span: 1-5 mm).

- Printer Setup: Level the build plate and ensure the filament path is unobstructed.

- Temperature Tower Print: Print a temperature calibration tower spanning 190-230°C (PLA) or 240-270°C (ABS). Visually inspect each section for stringing, gloss, and layer adhesion.

- Extrusion Multiplier Calibration: Print a single-wall calibration cube. Measure the actual wall thickness with calipers. Adjust the extrusion multiplier in the slicer:

New Multiplier = (Expected Width) / (Measured Width). - Cooling Fan Optimization: For PLA, set the cooling fan to 100% after the first layer. For ABS, fan should be off or very low (<20%) to prevent warping and delamination of roof layers.

- Print Test Coupon: Using optimized settings, print the channel test coupon.

- Analysis: Inspect channels under a microscope. Measure actual channel width vs. designed width. Check roof integrity. Iterate on extrusion multiplier and cooling settings until channel geometry matches design within 10% tolerance.

Visualizing the DfAM Decision Workflow

DOT Script for Microfluidic DfAM Decision Workflow

Title: DfAM Technology Selection Workflow for Microfluidics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for 3D Printed Microfluidic Device Development & Testing

| Item | Function | Example Product/Chemical |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Photopolymer | Primary structural material for vat polymerization of cell-contact devices. Must have low cytotoxicity. | Formlabs BioMed Amber, PR48; Digital ABS RGD875. |

| Water-Soluble Support Material | Enables printing of complex, enclosed channels that can be cleared post-print without manual intervention. | Stratasys SUP706 (for PolyJet); PVA filament (for FDM). |

| IPA (Isopropanol) | Standard solvent for washing uncured resin from vat-polymerized parts. High purity reduces residue. | Laboratory Grade IPA, >99% purity. |

| PDMS (Sylgard 184) | Elastomeric material for creating seals, membranes, or casting from 3D-printed masters. | Dow Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit. |

| UV-Curable Adhesive | For bonding 3D-printed parts to substrates (glass, PMMA) to seal channels optically. | Norland Optical Adhesive 81 (NOA81). |

| Fluorescent Tracers / Beads | For quantifying flow profiles, visualizing mixing efficiency, and identifying channel defects. | Fluorescein dye; 1-10 µm fluorescent polystyrene microspheres. |

| Surface Passivation Agent | Coats printed channels to reduce non-specific adsorption of biomolecules (proteins, cells). | Pluronic F-127, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). |

1. Introduction This application note details the end-to-end workflow for the rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices, situated within a thesis exploring advanced 3D printing methodologies. The transition from a digital concept to a functional physical prototype is critical for accelerating research in diagnostics, synthetic biology, and drug development. This protocol emphasizes iterative design, modern fabrication via vat photopolymerization (e.g., DLP, SLA), and validation.

2. Digital Design & Simulation Workflow The initial phase involves creating a 2D layout and translating it into a 3D model suitable for printing.

Protocol 2.1: CAD Model Preparation

- Software Selection: Utilize CAD software (e.g., AutoCAD, SolidWorks, or freeware like Fusion 360) for precise design.

- Channel Design: Define channel widths (typically 50-500 µm) and heights (50-300 µm). Maintain an aspect ratio (width:height) ≤ 5:1 to prevent roof sagging.

- Feature Integration: Design inlet/outlet ports (diameter ≥ 1.5 mm) for tubing interfacing. Include alignment markers for multi-layer bonding if required.

- Export: Save the final design as an STL (stereolithography) file with a resolution of 0.01 mm.

Table 1: Common Microfluidic Channel Dimensions and Applications

| Feature Size (µm) | Typical Application | Recommended Printing Technique |

|---|---|---|

| 50 - 100 | Single-cell traps, high-res mixing | High-res DLP, Two-Photon Polymerization |

| 100 - 200 | Standard cell culture, gradient generators | DLP, Projection SLA |

| 200 - 500 | Droplet generation, organ-on-chip chambers | SLA, DLP |

| > 500 | Macro-fluidic reservoirs, perfusion channels | FDM, SLA |

Protocol 2.2: Fluidic Simulation (Optional but Recommended)

- Tool Import: Import the 2D layout into finite element analysis (FEA) software (e.g., COMSOL Multiphysics, ANSYS Fluent).

- Parameter Setting: Define fluid properties (e.g., water: ρ=997 kg/m³, μ=0.001 Pa·s), boundary conditions (inlet velocity/pressure), and mesh size (~1/5 of smallest feature).

- Run Simulation: Execute a laminar flow study to visualize pressure drops, shear stress, and flow profiles.

- Iterate: Refine the design based on simulation results to optimize performance before printing.

3. 3D Printing & Post-Processing Protocol This core protocol focuses on using a high-resolution DLP printer for device fabrication.

Protocol 3.1: Print Preparation & Slicing

- Resin Selection: Choose a biocompatible, water-resistant photopolymer resin (e.g., Formlabs Dental SG or proprietary acrylic-based resins).

- Orientation: Orient the device at a 10-45° angle to the build platform to minimize stair-stepping on critical channel surfaces and reduce suction forces.

- Support Generation: Auto-generate light-touch supports for overhangs, ensuring they are not placed inside fluidic channels.

- Slice Parameters: Set layer height to 25-50 µm. Adjust exposure time per layer based on resin datasheet (e.g., 2-8 seconds).

Protocol 3.2: Printing & Post-Processing

- Print Execution: Initiate print. Monitor first layers for adhesion.

- Cleaning: Post-print, submerge the part in isopropanol (IPA) in an ultrasonic bath for 3-5 minutes to remove uncured resin.

- Support Removal: Carefully detach all support structures using flush cutters.

- Post-Curing: Cure the device under a 405 nm UV lamp for 10-20 minutes to ensure complete polymerization and improve mechanical stability.

- Surface Inspection: Inspect channels under a stereo microscope for defects or residual resin.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of 3D Printing Modalities for Microfluidics

| Method | Typical XY Resolution (µm) | Z Resolution (Layer Height) | Print Speed | Material Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLP / mSLA | 25 - 100 | 10 - 50 µm | Fast (parallel layer cure) | Moderate | High-resolution, rapid iteration |

| Two-Photon Polymerization | < 1 | 0.1 - 1 µm | Very Slow (point-by-point) | Very High | Nanofluidic, ultra-high complexity |

| Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | 100 - 300 | 50 - 200 µm | Moderate | Low | Macroscopic fixtures, rough prototypes |

| Inkjet 3D Printing | 20 - 50 | 5 - 30 µm | Moderate | High | Multi-material, embedded components |

4. Bonding, Functionalization & Assembly Creating a sealed, functional device is critical.

Protocol 4.1: Bonding to Substrate (Glass Slide)

- Surface Activation: Treat the bottom of the 3D-printed device and a clean glass slide with oxygen plasma (e.g., 100 W, 30 sec, 0.5 mBar O₂).

- Alignment & Contact: Immediately bring the activated surfaces into contact, applying gentle, uniform pressure.

- Thermal Annealing: Place the bonded assembly on a hotplate at 60°C for 15-30 minutes to strengthen the irreversible bond.

Protocol 4.2: Channel Surface Functionalization

- PBS Rinse: Flush channels with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Protein Coating (for cell adhesion): Introduce a solution of 50 µg/mL fibronectin or poly-D-lysine in PBS. Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Blocking: Flush with 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 minutes to block non-specific binding sites.

- Rinse: Flush with cell culture medium prior to cell seeding.

5. Validation & Functional Testing Protocol Protocol 5.1: Hydrodynamic Performance Test

- Setup: Connect device inlets to a programmable syringe pump via biocompatible tubing (e.g., PTFE, 0.5 mm ID).

- Dye Perfusion: Perfuse a food dye or fluorescent dye (e.g., 10 µM fluorescein) at a set flow rate (Q = 1-100 µL/min).

- Imaging & Analysis: Capture flow using a high-speed camera or fluorescence microscope. Use ImageJ to measure flow front velocity and compare to theoretical values (Q = v*A).

Protocol 5.2: Biological Validation (Cell Seeding)

- Cell Preparation: Trypsinize and resuspend HUVECs or HeLa cells at 2x10⁶ cells/mL in complete medium.

- Seeding: Slowly introduce 20 µL of cell suspension into the main channel. Allow cells to settle and adhere for 15 minutes.

- Perfusion Culture: Connect the device to a perfusion system with medium reservoir. Maintain flow at 5-10 µL/min in an incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Viability Assay: After 24-48 hours, perfuse a Live/Dead stain (e.g., Calcein-AM/EthD-1). Image and calculate viability (>90% expected for non-cytotoxic devices).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials & Reagents

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Biocompatible Photopolymer Resin (e.g., Formlabs BioMed Clear) | Primary printing material; ensures cytocompatibility for cell-based assays. |

| Isopropanol (IPA), >99% purity | Post-processing solvent for washing uncured resin from printed parts. |

| Oxygen Plasma Cleaner | Activates polymer and glass surfaces to enable strong, irreversible bonding. |

| PTFE Microbore Tubing (ID: 0.5 mm, OD: 1/16") | Connects syringe pumps and reservoirs to device ports with minimal dead volume. |

| Programmable Syringe Pump | Provides precise, pulsation-free flow control for perfusion and experiments. |

| Fibronectin, Lyophilized | Extracellular matrix protein coating to promote cell adhesion in channels. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used as a blocking agent to passivate channel surfaces and prevent non-specific binding. |

| Fluorescein Sodium Salt | Fluorescent tracer for visualizing flow profiles, mixing efficiency, and leakage. |

| Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (e.g., Calcein AM/Ethidium homodimer-1) | Two-color fluorescence assay to assess cell health within the fabricated device. |

Visualization: Workflow and Validation Diagrams

Figure 1: Rapid Prototyping Iterative Workflow

Figure 2: Prototype Functional Testing Setup

Step-by-Step Protocols: Building and Applying Your 3D Printed Microfluidic Device

Application Notes

In the context of a thesis on 3D printing for rapid microfluidic device prototyping, the selection of an appropriate software stack is critical. This stack bridges the conceptual design of complex, millimeter- to micrometer-scale fluidic architectures with their physical realization via additive manufacturing. The workflow is bifurcated into Computer-Aided Design (CAD) for geometry creation and slicing for machine instruction generation. For research-grade microfluidic devices, key considerations include the ability to design precise, sealed channels (typically 100-500 µm), incorporate interconnects, and export watertight models in formats compatible with high-resolution printing technologies like stereolithography (SLA), digital light processing (DLP), and two-photon polymerization (2PP). The following notes detail the essential tools, their roles, and integration points.

Software Tool Comparison & Quantitative Data

Table 1: Comparison of Primary CAD Software for Microfluidic Device Design

| Software | Primary License Type | Key Feature for Microfluidics | Typical Learning Curve | Optimal Print Technology | Export Formats (Key) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SolidWorks | Commercial | Robust parametric design, advanced assembly mates for multi-part devices. | Steep | SLA, FDM, PolyJet | STL, STEP, 3MF |

| Fusion 360 | Freemium/Commercial | Cloud-based parametric & direct modeling, integrated CAM/simulation. | Moderate | SLA, FDM | STL, STEP, 3MF |

| FreeCAD | Open-Source | Parametric, modular workbenches (e.g., Part, PartDesign). | Steep | SLA, FDM | STL, STEP |

| AutoCAD | Commercial | Precision 2D drafting for mask creation (for lithography). | Moderate | DLP (mask-based) | DXF, DWG |

| Blender | Open-Source | Advanced organic/freeform modeling, boolean operations. | Very Steep | SLA, DLP | STL, OBJ |

| Shapr3D | Commercial | Intuitive touch/tablet-based direct modeling. | Shallow | SLA, FDM | STL, STEP |

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Slicing Software for High-Resolution 3D Printing

| Software | Primary Use | Key Microfluidic Feature | Support Generation | Critical Setting for Microfluidics | Typical Layer Height Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitubox | SLA/DLP (MSLA) | Advanced hollowing & drainage hole tools. | Excellent, automatic & manual | Exposure Time, Anti-Aliasing | 10 - 100 µm |

| PrusaSlicer | FDM, SLA (multi-tech) | Variable layer height for optimal speed/quality. | Excellent, customizable | Layer Height, Print Speed | 50 - 200 µm |

| Formlabs PreForm | Formlabs printers | Optimized, material-specific profiles. | Good, automatic only | Layer Thickness, Supports | 25 - 100 µm |

| Ultimaker Cura | FDM, SLA (emerging) | Extensive plugin marketplace (e.g., custom supports). | Very Good, customizable | Wall Thickness, Flow | 50 - 300 µm |

| Lychee Slicer | SLA/DLP (MSLA) | AI-supported support generation, advanced rafts. | Excellent, AI-assisted | Light-off Delay, Lift Speed | 10 - 150 µm |

| Nanoslicer (e.g., for Nanoscribe) | 2PP | Voxel-based control for sub-micron features. | Specialized (scaffolding) | Laser Power, Scan Speed | 0.1 - 10 µm |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing a Sealed Microfluidic Mixer for SLA Printing

Objective: Create a 3D model of a two-inlet, serpentine-channel mixer with outlet, ready for slicing.

Materials:

- CAD Software (e.g., Fusion 360).

- Target channel dimensions: Width: 200 µm, Height: 200 µm.

- Device footprint: 15 mm x 15 mm x 5 mm.

Methodology:

- Sketch Base Geometry: In the XY plane, sketch a 15x15 mm square. Extrude it to 5 mm (base substrate).

- Create Channel Negative: On the top face of the substrate, sketch the channel network. Use offset lines to define a 200 µm wide path for the serpentine. Ensure inlets/outlets extend to the device edge.

- Extrude Cut for Channels: Select the channel sketch and perform an "extrude cut" operation to a depth of 200 µm. This creates the channel trench.

- Create Roof Layer: Create a new component. Sketch a 15x15 mm rectangle on the top face of the substrate (covering channels). Extrude it upward by 1 mm to form the roof, fully encapsulating the channels.

- Add Fluidic Interconnects: On the roof component, sketch 1.5 mm diameter circles aligned over the channel inlets/outlets. Use the "extrude cut" tool to create through-holes.

- Combine Components: Use a "Boolean union" or "Combine" operation to merge the substrate and roof components into a single, sealed body.

- Export: Finalize the design. Export the final device as an STL or 3MF file with "high" resolution settings. Ensure the mesh is watertight (no gaps).

Protocol 2: Slicing a High-Resolution Microfluidic Device for DLP Printing

Objective: Prepare an STL file for printing on a DLP printer (e.g., 50 µm XY resolution) using a biocompatible resin.

Materials:

- Slicing Software (e.g., Chitubox v1.9.4).

- Device STL file from Protocol 1.

- Printer Profile: Asiga MAX UV.

- Resin: PEGDA (Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate).

Methodology:

- Import & Orient: Import the STL. Orient the device so that the channel roof is facing the build platform. This minimizes cross-sectional area during peeling, reducing suction forces.

- Hollowing (Optional): For large devices, use the "Hollow" tool to create a 1.5 mm thick outer shell. Add at least two 2.5 mm diameter "Drain Holes" to the non-critical bottom face to allow uncured resin to escape.

- Support Generation:

- Switch to "Support" mode.

- Set contact depth to 0.4 mm, contact diameter to 0.30 mm, and tip diameter to 0.15 mm for minimal scarring.

- Use the "Auto-Supports" function with a density of 75%.

- Manually add heavy supports to the first few layers of any large overhangs (e.g., the device edges).

- Remove any auto-supports that contact critical channel or sealing surfaces.

- Slice Settings Configuration:

- Layer Thickness: 50 µm.

- Normal Exposure Time: 4.0 s (calibrate per resin datasheet).

- Bottom Exposure Time: 35 s.

- Bottom Layers: 8.

- Lift Speed: 2 mm/s.

- Anti-Aliasing: Enable to 8x to reduce pixelation artifacts.

- Slice & Preview: Execute the slice. Use the layer-by-layer preview to visually inspect for any islands (unsupported areas) or potential resin traps.

- Export: Save the sliced file as a

.ctb,.phz, or printer-specific format.

Workflow & Logical Relationship Diagrams

Title: 3D Printing Software Stack Workflow for Microfluidics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Prototyping

Table 3: Essential Materials for 3D Printed Microfluidic Device Fabrication & Testing

| Item | Function in Prototyping | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Photopolymer Resin | Base material for SLA/DLP printing. Biocompatible variants (e.g., PEGDA, IBT) are essential for cell-based assays. | Formlabs Biomedical Resin, PEGDA (Sigma-Aldrich), Anycubic Plant-Based. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) (>99%) | Primary solvent for washing uncured resin from printed parts in post-processing. | Laboratory-grade IPA. |

| UV Curing Chamber | Provides uniform post-print curing to fully polymerize and strengthen the resin device. | Anycubic Wash & Cure Station, Formlabs Curing Unit. |

| Silicone Tubing (e.g., 1/16" ID) | Connects device ports to syringe pumps or fluid reservoirs for functional testing. | Platinum-cured silicone lab tubing. |

| Syringe Pump | Provides precise, controllable fluid flow (µL/min to mL/min) for device characterization. | Harvard Apparatus PHD ULTRA, NE-1000. |

| Surface Passivation Agent | Coats channel walls to prevent non-specific adsorption of proteins or cells (e.g., BSA, Pluronic F-127). | 1% w/v Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) solution. |

| Food Dye / Colored Ink | Visual tracer for qualitative flow visualization, mixing efficiency, and leak testing. | Commercial food coloring. |

| Leak Test Sealant | Applied to external ports/connections to ensure fluidic integrity during pressurization (e.g., epoxy). | Five-minute epoxy glue. |

| Digital Microscope / Profilometer | Measures actual printed channel dimensions, surface roughness, and feature fidelity. | Keyence VHX Series, Dino-Lite digital microscope. |

Within the context of rapid prototyping for microfluidic device research, achieving dimensional precision and channel fidelity is paramount. This document details the critical printing parameters—Layer Height, Exposure Time, and Print Orientation—and their synergistic impact on device performance. Optimized protocols are essential for creating leak-free, optically clear devices suitable for cell culture, droplet generation, and analyte detection.

Layer Height

Layer height directly influences Z-axis resolution, surface finish, and print time. For microfluidics, thinner layers produce smoother channel walls and finer vertical features, reducing post-processing.

Table 1: Layer Height Effects on Print Quality

| Layer Height (µm) | XY Fidelity | Vertical Resolution (Z) | Surface Roughness (Ra, µm) | Print Time Relative to 50µm | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Excellent | High | ~1.5 - 2.5 | +100% | High-resolution features, optical clarity critical. |

| 50 (Standard) | Very Good | Moderate | ~3.0 - 5.0 | Baseline (1x) | General channel networks (>100 µm width). |

| 100 | Good | Low | >7.0 | -35% | Prototyping large reservoirs, support structures. |

Exposure Time

Exposure time dictates the degree of photopolymerization, affecting cure depth, feature accuracy, and mechanical properties. Over-exposure causes blooming; under-exposure causes delamination.

Table 2: Exposure Time Optimization for 50µm Layers (Clear Resin)

| Parameter | Under-Exposure (<80% Optimal) | Optimal Range | Over-Exposure (>120% Optimal) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel Dimensional Error | +15 to +30% (wider) | ±5% | -10 to -20% (narrower) |

| Tensile Strength | Low (Delamination risk) | High | Brittle |

| Critical Cleaning Difficulty | High (Uncured resin in channels) | Low | Moderate |

Note: Optimal base exposure is resin and printer-specific. A typical range for 385-405nm LCD/DLP printers with standard clear resin is 1.5 - 3.0 seconds.

Print Orientation

Orientation manages the surface area of each layer, affecting support usage, anisotropy, and channel cross-sectional shape.

Table 3: Orientation Impact on Microfluidic Channel Geometry

| Orientation | Channel Deformation | Support Usage on Device | Anisotropy (XY vs. Z Strength) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat (0°) | Minimal XY distortion. Roof may sag. | Minimal (edges only). | Low | Best for channel width/height fidelity. |

| Vertical (90°) | Excellent roof/wall finish. Elliptical width distortion. | High (on one side). | High | Best for smooth internal surfaces and tall features. |

| Angled (45°) | Compromise between flat & vertical. | Moderate. | Moderate | Balanced approach for complex devices. |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Optimization

Protocol: Determining Optimal Exposure Time (Exposure Finder Test)

Objective: To empirically determine the ideal normal exposure time for a specific resin-printer combination. Materials: SLA/DLP 3D printer, clear photopolymer resin, exposure test model (e.g., AmeraLabs Town, Siraya Tech XP Finder). Procedure:

- Model Preparation: Slice the chosen calibration model at your target layer height (e.g., 50µm).

- Exposure Array: Print the model with a range of exposure times (e.g., 1.0s, 1.5s, 2.0s, 2.5s, 3.0s).

- Post-Processing: Wash and cure all parts identically per resin manufacturer specifications.

- Evaluation:

- Measure critical features (pins, holes, gaps) using a digital microscope or calipers.

- Visually inspect for feature coalescence (over-exposure) or failure to form (under-exposure).

- The time producing features closest to the CAD dimensions with minimal deformity is optimal.

Protocol: Evaluating Orientation-Dependent Channel Fidelity

Objective: Quantify the geometric distortion of microfluidic channels based on build orientation. Materials: CAD software, SLA/DLP 3D printer, clear resin, profilometer or micro-CT scanner. Procedure:

- Design: Create a test chip with an array of rectangular channels (e.g., 100µm x 100µm cross-section).

- Orientation: Slice and print identical chips at 0° (flat), 45°, and 90° (vertical) orientations.

- Post-Processing: Clean and cure identically. Carefully remove all supports.

- Measurement: Section the channels and image cross-sections using a microscope or micro-CT.

- Analysis: Measure achieved width (Wa) and height (Ha). Calculate % deviation from designed (Wd, Hd): Deviation = [(Wa - Wd) / W_d] * 100.

Protocol: Layer Height for Optical Clarity

Objective: Assess the impact of layer height on the optical transparency of device walls for microscopy. Materials: Printer, clear resin, spectrophotometer or light microscope. Procedure:

- Print: Fabricate flat, solid plaques (1mm thick) at varying layer heights (25µm, 50µm, 100µm).

- Post-Process: Apply identical washing and curing.

- Test: Measure light transmission (%) at 550nm wavelength using a spectrophotometer. Alternatively, image a standard sample (e.g., fluorescent beads) through each plaque using a microscope and quantify signal-to-noise ratio.

Visualized Workflows and Relationships

Diagram Title: Microfluidic Print Parameter Optimization Workflow

Diagram Title: Primary Effects of Key Printing Parameters

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for High-Precision Microfluidic Prototyping

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Biocompatible Clear Resin (e.g., Formlabs Biomed Amber, PEGDA-based resins) | Provides cytocompatibility for cell-laden devices, necessary for biological assays. Offers low autofluorescence. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA, >99%) or Bio-Safe Alternatives (e.g., Tripropylene Glycol Monomethyl Ether) | Standard washing solvent to remove uncured resin from intricate channels. Bio-safe alternatives reduce toxicity. |

| Post-Curing Chamber (405nm LED) | Ensures complete polymerization, maximizes mechanical strength, and stabilizes material properties. |

| Digital Microscope or Optical Profilometer | Critical for non-destructive measurement of channel dimensions, surface roughness, and defect identification. |

| Plasma Surface Treater (Air or Oxygen) | Creates hydrophilic surface on cured resin, enabling spontaneous aqueous filling of microchannels. |

| Silanizing Agent (e.g., (Tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl) trichlorosilane) | Renders channel surfaces hydrophobic, essential for applications like droplet generation. |

| Syringe Tips & Tubing (e.g., Polyurethane, 0.5mm ID) | For interfacing printed devices with fluidic control systems (syringe pumps, pressure controllers). |

| Optical Adhesive (UV-Curing, Index-Matching) | For bonding printed layers or sealing devices to glass coverslips for high-resolution microscopy. |

Within the thesis on "3D Printing Methods for Rapid Microfluidic Device Prototyping," post-processing is a critical, non-negotiable phase that directly determines the functional viability of printed devices. For applications in drug development and biomedical research, unoptimized post-processing leads to channel occlusion, surface-induced analyte adsorption, and structural failure, invalidating experimental results. This document provides detailed Application Notes and Protocols to standardize these crucial steps for researchers and scientists.

Support Removal for Microfluidic Channels

Application Notes

Support material removal is the most delicate step in microfluidic device fabrication. Residual supports within micron-scale channels catastrophically affect fluid dynamics and particle flow. The chosen method must balance efficacy with the preservation of the primary resin's structural integrity and feature fidelity.

Quantitative Data & Methods Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Support Removal Techniques for Resin-Based Microfluidics

| Technique | Recommended For | Typical Duration | Efficacy (% Material Removal) | Risk to Fine Features | Key Consideration for Microfluidics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Immersion (IPA, Ethanol) | Standard & Tough Resins | 10-30 min | >99% | Low-Moderate | Can cause resin swelling; requires multiple washes. |

| Heated Bath (NaOH Solution, ~60°C) | Soluble Supports (e.g., PVA) | 1-2 hours | ~100% | Very Low | Ideal for complex internal channels; pH must be neutralized after. |

| Ultrasonic Agitation | Complementary to immersion | 2-5 min cycles | Enhances primary method | High | Can crack thin channel walls; use with extreme caution. |

| Mechanical (Flush Syringe) | Large, accessible channels | Varies | ~80-95% | Moderate | Manual pressure control is critical to avoid delamination. |

| Post-Curing Dissolution | Specialized resins (e.g., PEGDA) | Varies | High | Low | Material-specific; integrates removal with final curing. |

Detailed Protocol: Solvent Immersion with Agitated Rinse for Standard Resin Supports

Objective: To completely remove support material from internal microchannels of a stereolithography (SLA)-printed device without damaging features >100 µm.

Materials & Reagents:

- Printed microfluidic device with supports.

- Laboratory-grade Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA), ≥99%.

- Two ultrasonic cleaners (optional, for gentle agitation only).

- Soft-bristle brushes and dental picks.

- Lint-free wipes.

- Compressed air or nitrogen gun.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Nitrile gloves, safety glasses, lab coat.

Procedure:

- Initial Detachment: Gently remove the device from the build platform. Use flush-cutting snips to remove large, external support structures. Peel supports away from the device along the build direction (Z-axis), not laterally.

- Primary Solvent Bath: Submerge the device in a bath of fresh IPA at room temperature for 15 minutes. For devices with channels <500 µm, gentle manual swirling of the bath is preferred over ultrasonication.

- Agitated Secondary Rinse: Transfer the device to a second bath of clean IPA. Place this bath in an ultrasonic cleaner filled with water (acting as a coupling medium). Run the ultrasonic cleaner at a low frequency (40 kHz) and low power for no more than 60-second intervals. Inspect channels between intervals.

- Mechanical Assistance: For visible support remnants at channel inlets/outlets, use a soft-bristle brush or blunt dental pick under a stereomicroscope. Follow with a flush of IPA from a syringe.

- Final Rinse & Dry: Perform a final static rinse in a third bath of clean IPA for 5 minutes. Remove the device and pat dry with lint-free wipes. Use a low-pressure stream of compressed air or nitrogen to evaporate residual IPA and dry channels completely. Do not oven dry at this stage if post-curing is pending.

Diagram Title: Support Removal Protocol Workflow

Curing for Functional Stability

Application Notes

Post-curing polymerizes residual monomers, increasing the device's mechanical strength, chemical resistance, and biocompatibility—essential for long-term or biologically active fluid experiments. Over-curing can induce brittleness and yellowing.

Quantitative Data

Table 2: Post-Curing Parameters for Common Microfluidic Resins

| Resin Type (Example) | Recommended Wavelength | Power Density | Typical Duration | Temperature | Key Outcome for Microfluidics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Clear (e.g., Formlabs RS-F2-GPCL) | 405 nm | 10-30 mW/cm² | 30-60 min | 60°C | Maximizes transparency for imaging; stabilizes swelling. |

| Biocompatible (e.g., Formlabs MED610) | 405 nm | 20-40 mW/cm² | 45-90 min | 40-60°C | Ensures cytotoxicity-free surfaces for cell culture. |

| Flexible (e.g., Agilus30) | 385-405 nm | 5-15 mW/cm² | 60-120 min | RT - 40°C | Balances elasticity with dimensional stability for pneumatic valves. |

| High-Temp (e.g., RIgid10K) | 395-410 nm | 30-50 mW/cm² | 60+ min | 80-100°C | Enhances Tg for applications involving elevated temperatures. |

Detailed Protocol: Thermal-Assisted UV Post-Curing

Objective: To fully polymerize a clear resin microfluidic device, optimizing optical clarity and hydrolysis resistance.

Materials & Reagents:

- Support-removed, dry device.

- UV post-curing chamber (wavelength 385-405 nm).

- Programmable thermal oven or curing chamber with heating.

- UV light power meter (for calibration).

- IPA and lint-free wipes.

Procedure:

- Pre-Cure Clean: Wipe the device with IPA to remove any surface contaminants or oils.

- Calibration: Verify the UV irradiance at the device placement plane using a power meter. Adjust distance or time to achieve target dose (e.g., 20 J/cm²).

- Thermal-Assisted Cure: Place the device in the curing chamber. If the chamber has integrated heating, set to the resin-specific temperature (e.g., 60°C for standard clear). If not, pre-heat the device in an oven at the target temperature for 10 minutes before transferring to the UV chamber.

- Curing Cycle: Initiate UV exposure for the recommended duration (e.g., 30 minutes at 60°C). Ensure the device is rotated 180° halfway through for even exposure if the light source is not omnidirectional.

- Cooling: Allow the device to cool gradually to room temperature inside the closed, UV-off chamber or in a dust-free environment to prevent thermal stress cracking.

Surface Treatment and Functionalization

Application Notes

The native hydrophobicity of most photopolymers leads to poor wetting, bubble trapping, and protein adsorption. Surface treatment modifies the channel's physicochemical properties to suit the application, from passive hydrophilic flow to active biorecognition sites.

Quantitative Data & Method Comparison

Table 3: Surface Treatment Techniques for 3D-Printed Microfluidics

| Technique | Mechanism | Effect on Water Contact Angle (WCA) | Durability | Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Plasma | Creates polar -OH, C=O groups | 100° → <10° | Days to weeks | Short-term hydrophilic flow; prepares surface for bonding. |

| Surfactant Addition (e.g., Tween 20) | Adsorption to surface | Moderate reduction | Single experiment | Prevents protein adhesion in assays; used in buffer. |

| Silane Functionalization | Covalent siloxane bond | Tunable (hydrophobic/philic) | Permanent | Creates epoxy, amine, or thiol groups for biomolecule conjugation (e.g., antibodies). |

| PVA Coating | Hydrophilic polymer layer | 100° → ~40° | Moderate | Provides a consistent, low-fouling surface for particle synthesis. |

| Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Assembly | Electrostatic multilayer deposition | Tunable | High | Creates tailored surface charge and chemistry for cell studies. |

Detailed Protocol: Silane-Based Amine Functionalization for Protein Immobilization

Objective: To covalently attach an amine-terminated monolayer to microchannel surfaces for subsequent conjugation of biomarkers or enzymes.

Materials & Reagents:

- (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES): Coupling agent providing primary amine groups.

- Anhydrous Toluene: Solvent for silane reaction.

- Oxygen Plasma Cleaner: For surface activation.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4: For rinsing.

- Glutaraldehyde (optional): Crosslinker for direct protein attachment.

- Nitrogen gun.

Procedure:

- Surface Activation: Place the cured device in a plasma cleaner. Treat with oxygen plasma at medium power (50-100 W) for 1-2 minutes. This creates a dense, reactive layer of hydroxyl (-OH) groups.

- Silane Solution Preparation: In a glove box or under dry nitrogen, prepare a 2% (v/v) solution of APTES in anhydrous toluene. Mix thoroughly.

- Functionalization: Immediately after plasma treatment, immerse the device in the APTES solution for 1 hour at room temperature. Ensure channels are fully filled via vacuum degassing or syringe flushing.

- Rinsing: Remove the device and rinse thoroughly with anhydrous toluene to remove physisorbed silane, followed by a rinse with pure ethanol.

- Curing: Bake the device at 110°C for 30 minutes to complete the covalent siloxane (Si-O-Si) bond formation to the surface.

- Verification: Confirm functionalization via a contact angle measurement (should be moderately hydrophilic) or colorimetric assay like Acid Orange II.

- Next Step (e.g., Protein Conjugation): The amine-coated device can now be treated with glutaraldehyde (a linker) or activated esters (e.g., NHS esters) to covalently immobilize proteins.

Diagram Title: Surface Amine Functionalization Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents for Post-Processing 3D-Printed Microfluidics

| Item | Function in Post-Processing | Critical Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA), ≥99% | Primary solvent for dissolving uncured resin and support material. | Must be kept anhydrous and changed frequently. Multi-bath process is essential for complete cleaning. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Forms a covalent, amine-terminated monolayer on activated oxide surfaces for biomolecule conjugation. | Must be used under anhydrous conditions. Moisture causes self-polymerization and uneven coating. |

| Oxygen Plasma | Activates polymer surfaces by creating reactive hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, enabling bonding and functionalization. | Effect is time-sensitive; proceed to next step within 10 minutes of treatment. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4 | Standard rinsing and hydration buffer for biologically relevant functionalization and to prepare channels for aqueous solutions. | Use to remove salts and unbound reagents after surface reactions before introducing biomolecules. |

| Tween 20 (Polysorbate 20) | Non-ionic surfactant added to running buffers to passivate surfaces, reducing non-specific protein adsorption and bubble formation. | Typical concentration 0.1% v/v. Critical for immunoassays and cell-based studies in printed devices. |

| Glutaraldehyde (25% Aqueous Solution) | Homobifunctional crosslinker for covalently linking amine-functionalized surfaces to proteins (via lysine residues). | Use at low concentration (0.5-2.5%) for short durations (15-30 min) to avoid excessive crosslinking and brittleness. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) Solution | Forms a hydrophilic, sacrificial coating inside channels to promote wetting and can be used as a temporary pore-forming material. | A 1-5% w/v solution is flushed and dried in channels. Dissolves upon first aqueous use, leaving a wetted surface. |

Bonding and Sealing Methods for Creating Enclosed Fluidic Networks

Within a broader thesis on 3D printing methods for rapid microfluidic device prototyping, the final and critical step is reliable bonding and sealing to create enclosed, leak-free fluidic networks. This phase translates a printed substrate into a functional device. The choice of bonding method is dictated by the 3D printing material, desired feature resolution, chemical compatibility, and the intended pressure regime of the application. These protocols are essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to implement rapid prototyping workflows for microfluidic assay and device development.

Key Bonding Methods: Application Notes

The following table summarizes the primary bonding techniques applicable to 3D-printed microfluidic devices, based on current literature and practices.

Table 1: Comparison of Bonding Methods for 3D-Printed Microfluidics

| Method | Compatible Materials (Examples) | Estimated Bond Strength (kPa) | Max Temp/Pressure Tolerance | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesive Bonding | PLA, ABS, PETG, Resins, Glass | 200 - 800 | 60°C / ~200 kPa | Simple, fast, material-agnostic | Potential channel clogging, chemical incompatibility |

| Thermal Fusion | PLA, ABS, PMMA | 500 - 1500 | Tg of material / ~500 kPa | No adhesives, good strength | Feature distortion, requires precise temperature control |

| Solvent Bonding | ABS, PMMA, PS, some Resins | 400 - 1200 | Tg of material / ~400 kPa | Strong, monolithic-like bond | Solvent attack on fine features, safety concerns |

| Surface Activation | PDMS, Plastics, Glass | 300 - 1000 (PDMS) | Varies / ~300 kPa | High-quality seals for PDMS | Requires equipment (plasma cleaner) |

| Mechanical Fastening | All (with design) | 100 - 600 (seal-dependent) | Gasket-dependent / ~150 kPa | Reversible, no chemical treatment | Prone to leaks at high pressure, more complex design |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Oxygen Plasma Bonding for PDMS-to-Glass/PDMS (Surface Activation)

This protocol is standard for sealing PDMS devices, often used as a mold cast from a 3D-printed master.

I. Materials & Equipment

- PDMS slab (base:curing agent 10:1, cured).

- Glass slide or another PDMS slab.

- Oxygen plasma cleaner (e.g., Harrick Plasma, Femto).

- Isopropyl alcohol (IPA).

- Nitrogen gun or clean compressed air.

II. Procedure

- Surface Preparation: Clean the glass slide thoroughly with IPA and dry with nitrogen. Clean the PDMS surface with adhesive tape to remove debris, followed by an IPA rinse and nitrogen dry.

- Plasma Treatment: Place both pieces with bonding surfaces facing up in the plasma chamber. Evacuate the chamber and introduce oxygen gas. Treat at high RF power (e.g., 30 W) for 30-60 seconds.

- Bonding: Immediately after treatment, carefully bring the activated PDMS surface into conformal contact with the glass slide. Apply gentle, even pressure starting from one edge to avoid trapping air bubbles.

- Post-Processing: Bonding is immediate. For increased strength, place the bonded assembly on a hotplate at 80°C for 10-15 minutes.

Protocol 3.2: Thermal Fusion Bonding for 3D-Printed PLA Devices

I. Materials & Equipment

- 3D-printed PLA substrate (with fluidic channels).

- 3D-printed PLA flat lid or cover slab.

- Hot press or programmable thermal press with flat plates.

- Shim stock or spacers.

- Digital calipers.

II. Procedure

- Part Preparation: Print substrate and lid with 100% infill. Lightly sand mating surfaces with fine-grit sandpaper (e.g., P600) to ensure flatness. Clean with IPA and dry.

- Parameter Determination: Determine the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the PLA filament (typically ~60°C). The bonding temperature (Tbond) should be slightly above Tg (e.g., Tg + 5°C = ~65°C).

- Alignment: Manually align the lid onto the substrate.

- Thermal Pressing: Place the aligned stack between two flat metal plates in the hot press. Insert shims around the device to control final thickness and prevent excessive flow. Heat to T_bond (65°C) and apply a low pressure (e.g., 10-20 kPa) for 15-20 minutes.

- Cooling: Cool the press to below T_g (to ~40°C) under maintained pressure before removing the bonded device.

Protocol 3.3: Solvent Bonding for 3D-Printed ABS Devices

I. Materials & Equipment

- 3D-printed ABS substrate and lid.

- Solvent: Acetone or 60:40 Acetone:Ethanol mixture.

- Fume hood.

- Glass dish.

- Weight or clamp.

II. Procedure

- Part Preparation: Smooth mating surfaces with fine sandpaper. Clean with IPA to remove oil and particles.

- Solvent Application: In a fume hood, lightly wet a lint-free wipe with the acetone mixture. Gently and uniformly wipe the bonding surface of the lid only. Alternatively, expose the surface to acetone vapor for 5-10 seconds by holding it over the glass dish.

- Assembly: Immediately align and place the lid onto the substrate. Apply gentle, even pressure.

- Curing: Place a light weight (~1 kPa) on top of the assembly. Allow it to cure for at least 2-4 hours at room temperature. Full bond strength develops over 24-48 hours.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Bonding Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in Bonding & Sealing |

|---|---|

| Oxygen Plasma Cleaner | Generates reactive oxygen species to create hydrophilic silanol groups on PDMS and other surfaces, enabling irreversible covalent bonding. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | The ubiquitous elastomer for soft lithography; bonds to itself and glass via plasma activation. |

| Sylgard 184 Kit | The standard two-part (base & curing agent) silicone elastomer kit for casting PDMS devices. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | A silane coupling agent used to promote adhesion between dissimilar materials (e.g., glass to resin) or to modify surface chemistry. |

| UV-Curable Optical Adhesive (e.g., NOA 81) | A low-viscosity, solvent-free adhesive cured by UV light for bonding transparent polymers and creating watertight seals. |

| Cyanoacrylate (CA) "Super Glue" | Fast-setting adhesive for quick, high-strength prototyping bonds on plastics; can clog channels if applied imprecisely. |

| Silicone Gaskets & O-Rings | Used in mechanical fastening methods to provide a compressive seal between device layers, enabling reversibility. |

| Programmable Hot Press | Provides precise control of temperature, pressure, and time for thermal fusion bonding of thermoplastics. |

Visualization: Bonding Method Decision Workflow

Title: Bonding Method Selection for 3D-Printed Fluidics

This Application Note details experimental case studies leveraging rapid 3D-printed microfluidic devices. Framed within a thesis on additive manufacturing for microfluidic prototyping, we present three focused applications demonstrating the agility of 3D printing in developing functional research platforms for cell culture, droplet-based assays, and biosensing.

Case Study 1: 3D-Printed Perfusion Bioreactor for HepG2 Spheroid Culture

Objective: To maintain functional HepG2 spheroids for 7 days in a sterile, perfusion-enabled 3D-printed device. Device Fabrication: A two-part bioreactor was printed using a commercial Digital Light Processing (DLP) printer with biocompatible resin (e.g., Formlabs Dental SG). Post-printing, parts were washed in isopropanol, UV-post-cured, and autoclaved for sterility. Key Advantage: The entire design-to-device cycle was completed in under 24 hours.

Protocol:

- Seed the device: Inject a suspension of 1x10⁶ HepG2 cells/mL in complete DMEM into the central culture chamber.

- Allow spheroid formation: Let the device sit static in a 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator for 48 hours.

- Initiate perfusion: Connect the device inlet to a syringe pump via sterile tubing. Begin perfusing with complete DMEM at 10 µL/min.

- Monitor and sample: Perfuse for 7 days. Collect effluent from the outlet daily for analysis (e.g., albumin secretion via ELISA).

- Endpoint analysis: On day 7, stop perfusion, introduce Calcein-AM/EthD-1 live/dead stain into the chamber, incubate for 45 minutes, and image via confocal microscopy.

Results & Quantitative Data: Table 1: HepG2 Spheroid Viability and Function in 3D-Printed Perfusion Bioreactor

| Metric | Static Culture (Day 7) | Perfusion Culture (Day 7) | Assay Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability (%) | 65.2 ± 7.1 | 92.5 ± 4.3 | Live/Dead Fluorescence |

| Spheroid Diameter (µm) | 151.3 ± 21.4 | 185.7 ± 18.9 | Brightfield Imaging |

| Albumin Secretion Rate (ng/day/10⁶ cells) | 35.1 ± 5.2 | 108.6 ± 12.7 | ELISA of Daily Effluent |

| Urea Production Rate (µg/day/10⁶ cells) | 8.4 ± 1.3 | 22.3 ± 3.1 | Colorimetric Assay |

Case Study 2: Rapid Prototyping of Droplet Generators for Single-Cell Encapsulation

Objective: To compare the performance of 3D-printed flow-focusing droplet generators with traditional PDMS devices. Device Fabrication: Nozzle designs (20µm, 50µm, 100µm orifice diameters) were printed using a high-resolution stereolithography (SLA) printer. Channels were rendered hydrophilic via a brief (30 sec) oxygen plasma treatment.

Protocol:

- Device priming: Flush the oil channel with HFE-7500 oil containing 2% fluorosurfactant.

- Prepare phases: Continuous phase (CP): Fluorinated oil with 2% surfactant. Dispersed phase (DP): PBS with 0.5% PEGDA and 1x10⁶ cells/mL.

- Generate droplets: Using dual syringe pumps, infuse DP at 200 µL/hr and CP at 800 µL/hr.

- Characterize droplets: Collect droplets and image under a high-speed camera. Use ImageJ to analyze droplet diameter and cell encapsulation.

- Gelation (if applicable): Expose collected droplets to UV light (365 nm, 100 mW/cm² for 10 sec) to polymerize the PEGDA, forming cell-laden microgels.

Results & Quantitative Data: Table 2: Performance of 3D-Printed vs. Soft Lithography Droplet Generators

| Parameter | PDMS Device (50µm design) | 3D-Printed Device (50µm design) | Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet Diameter (µm) | 51.3 ± 2.1 | 53.8 ± 3.7 | High-Speed Imaging (n=200) |

| Coefficient of Variation (%) | 1.8 | 3.5 | (SD/Mean)*100 |

| Generation Frequency (Hz) | 1200 | 950 | High-Speed Camera Count |

| Single-Cell Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | ~33% (Poisson) | ~29% (Poisson) | Microscopy Count of >500 droplets |

| Device Fabrication Time | ~24-48 hours | ~2 hours | Design to final device |

Case Study 3: Integrated Electrochemical Biosensor for Glucose Monitoring

Objective: To fabricate a monolithic 3D-printed device with integrated electrodes for amperometric glucose sensing. Device Fabrication: A three-electrode system (WE: Carbon-black composite, CE/RE: Ag/AgCl) was printed in a single run using a multi-material extrusion printer (e.g., BioBot Series 2). The microfluidic channel was printed atop the electrodes.

Protocol:

- Enzyme functionalization: Pipette 5 µL of glucose oxidase solution (10 mg/mL in PBS) onto the working electrode. Let it adsorb for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Device assembly: Bond a clear film lid to the top of the channel using a silicone adhesive.

- Calibration: Connect electrodes to a potentiostat. Perfuse PBS with increasing concentrations of glucose (0, 2, 5, 10 mM) at 50 µL/min. Apply +0.6V vs. Ag/AgCl and record steady-state current.

- Sample measurement: Perfuse unknown sample (e.g., cell culture media) and record current response.

- Data analysis: Plot calibration curve (current vs. [glucose]) and calculate sample concentration from the linear fit.

Results & Quantitative Data: Table 3: Performance of Monolithic 3D-Printed Glucose Biosensor

| Performance Metric | Value | Conditions / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 0.1 - 15 mM | R² = 0.998 |

| Sensitivity | 125.4 nA/mM·cm² | From slope of calibration curve |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 50 µM | Signal-to-Noise Ratio = 3 |

| Response Time (t90) | < 5 seconds | Time to 90% steady-state current |

| Interference Test | <5% signal change | Against 0.1 mM ascorbic acid |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Applications

| Item | Function / Application | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible DLP/SLA Resin | For printing cell-contact devices; must be non-cytotoxic post-curing. | Formlabs BioMed Clear, Dental SG |

| Fluorosurfactant | Stabilizes water-in-fluorocarbon droplets, prevents coalescence. | RAN Biotechnologies 008-FluoroSurfactant |

| HFE-7500 Oil | Biocompatible, dense fluorinated oil for droplet generation. | 3M Novec 7500 Engineered Fluid |

| Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate (PEGDA) | Photopolymerizable hydrogel precursor for cell encapsulation in droplets. | Sigma-Aldrich, MW 700 |

| Glucose Oxidase | Enzyme for biosensor functionalization; catalyzes glucose oxidation. | Aspergillus niger, ≥100 U/mg |

| Calcein-AM / EthD-1 | Live/dead viability assay stain for 3D cell cultures. | Thermo Fisher Scientific L3224 |

| Conductive Graphene/ Carbon-black Composite Filament | For printing functional electrochemical electrodes via FDM. | BlackMagic 3D Conductive Graphene |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Workflow for 3D-Printed Perfusion Cell Culture

Amperometric Glucose Sensing Pathway

Solving Print Failures and Enhancing Performance: A Troubleshooting Handbook

Within the research thesis on 3D printing methods for rapid microfluidic device prototyping, a critical barrier to widespread adoption is the consistent production of functional, leak-free devices. This application note details the predominant failure modes encountered when using vat photopolymerization (e.g., stereolithography - SLA, digital light processing - DLP) for microfluidic fabrication. Understanding and mitigating channel collapse, leaks, resin incompatibility, and warping is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to use 3D printing for creating robust prototypes for cell studies, organ-on-a-chip models, and diagnostic devices.

Channel Collapse

Channel collapse refers to the deformation or complete closure of unsupported microfluidic channels during or after the printing process, primarily due to insufficient mechanical strength of the green-state resin or inadequate support structures.

Quantitative Analysis of Contributing Factors

Table 1: Parameters Influencing Channel Collapse in VAT Photopolymerization

| Parameter | Typical Risk Range | Recommended Safe Range | Effect on Structural Integrity |

|---|---|---|---|