Revolutionizing Drug Discovery: How Microfluidic Devices Enable High-Throughput Screening and Precision Medicine

This article explores the transformative role of microfluidic technology in high-throughput drug discovery and development.

Revolutionizing Drug Discovery: How Microfluidic Devices Enable High-Throughput Screening and Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of microfluidic technology in high-throughput drug discovery and development. It provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of how Lab-on-a-Chip systems, organ-on-chip models, and droplet microfluidics are overcoming the limitations of traditional methods. The scope covers foundational principles, key methodological applications in screening and toxicity testing, practical strategies for troubleshooting common device challenges, and rigorous approaches for validating microfluidic platforms against established standards. By integrating the latest research and commercial trends, this resource serves as a practical guide for leveraging microfluidics to accelerate pharmaceutical R&D, reduce costs, and advance personalized medicine.

Microfluidics 101: Core Principles and Why It's a Game-Changer for Modern Drug Discovery

Microfluidics is the science and technology of systems that process or manipulate small volumes of fluids (10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹⁸ liters), using channels with dimensions ranging from tens to hundreds of micrometers [1]. This field has revolutionized various aspects of the pharmaceutical industry, including drug discovery, development, and analysis [1]. The key concept involves integrating laboratory operations into a simple micro-sized system, a principle often referred to as "Lab-on-a-Chip" (LOC) or "Micro-Total Analysis Systems" (µTAS) [2]. Fluids at this microscale behave differently than at macroscopic scales, with factors such as laminar flow, capillary effects, and surface tension dominating their behavior [3]. These unique characteristics are leveraged to create powerful tools for high-throughput drug discovery research, enabling scientists to conduct extremely precise experiments and evaluate biological samples with unmatched precision [1].

Fundamental Principles and Advantages

Microfluidic systems exploit the distinct physical and chemical properties of liquids and gases at the microscale. The flow is typically laminar, which allows for highly predictable fluid behavior and precise control over the microenvironment [3]. This precise control enables the creation of highly efficient and reproducible systems for chemical reactions and biological assays.

The table below summarizes the core advantages of microfluidic systems over conventional macroscopic methods, particularly in the context of drug discovery research.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Microfluidic Systems in Drug Discovery

| Advantage | Impact on Drug Discovery Research |

|---|---|

| Minimal Reagent Consumption | Reduces global cost of applications; enables work with precious or expensive compounds [4] [2]. |

| High-Throughput Screening | Allows thousands of tests to be run in parallel, dramatically accelerating the hit identification and optimization phases [1] [5]. |

| Enhanced Parameter Control | Provides superior control over the cellular microenvironment (e.g., shear stress, concentration gradients), leading to more physiologically relevant data [3] [2]. |

| Fast Reaction Times | Shortens experimental times due to small volumes and short diffusion distances [4] [5]. |

| Process Automation & Integration | Automates multi-step reactions within a single device, minimizing manual handling and improving reproducibility [5] [2]. |

| Excellent Data Quality | High precision and controllability lead to robust and high-quality data [2]. |

Applications in High-Throughput Drug Discovery

Microfluidic technology has become a transformative tool across the entire drug discovery and development pipeline, from initial target selection to preclinical studies [4].

Target Selection and Validation

The first step in drug discovery is to identify a biological target, such as a protein, that can be modulated by a drug molecule [4]. Microfluidic devices facilitate this by enabling high-sensitivity protein analysis.

- Protein Analysis in Single Cells: Integrated devices can manipulate, lyse, label, separate, and quantify the protein contents of individual cells, which is crucial for understanding signal transduction pathways [4].

- Protein Crystallization: Microfluidic platforms, such as those using droplet-based generators or free interface diffusion, allow for high-throughput protein crystallization trials with minimal sample consumption, aiding in structural characterization of targets [4].

- Ligand-Binding Studies: These devices characterize molecular interactions (e.g., IC₅₀, Kd) with high sensitivity and throughput, identifying promising drug-target interactions early on [4].

Hit Identification and Optimization

This phase involves screening vast libraries of compounds to identify "hit" molecules that interact with the selected target. Microfluidics excels here.

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Microfluidic multiplexed systems containing thousands of microchambers, microwell arrays, or microvalves perform HTS with higher sensitivity and shorter reaction times compared to conventional methods, while significantly reducing reagent volumes and costs [1] [5].

- Droplet-Based Microfluidics: By encapsulating individual cells or reagents in picoliter droplets, millions of distinct experiments can be conducted in parallel, vastly increasing screening throughput [4] [5].

Preclinical Studies: Organs-on-Chips

A major innovation in microfluidics is the development of Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) models. These are 3D microdevices that aim to replicate the key functions of living human organs, providing more physiologically relevant and human-predictive data than traditional 2D cell cultures or animal models [3] [2].

- Heart-on-Chip (HoC): These systems use microchannels, often made of PDMS, to create microenvironments that mimic the heart's architecture and mechanical forces, such as pulsatile flow and shear stress [3]. They incorporate 3D co-cultures of cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts, allowing for detailed study of cardiac disease models and drug responses [3].

- Multi-Organ Chips: Integrated systems (e.g., heart-liver platforms) enable researchers to study systemic drug effects, metabolism, and toxicity in a interconnected human-relevant system [3].

- Personalized Medicine: The incorporation of patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into these chips allows for the creation of personalized disease models and the testing of therapeutic strategies on a patient-specific cellular phenotype [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Drug Screening Using a Microwell Array Chip

This protocol describes a method for screening a compound library against a cellular target.

Workflow Overview:

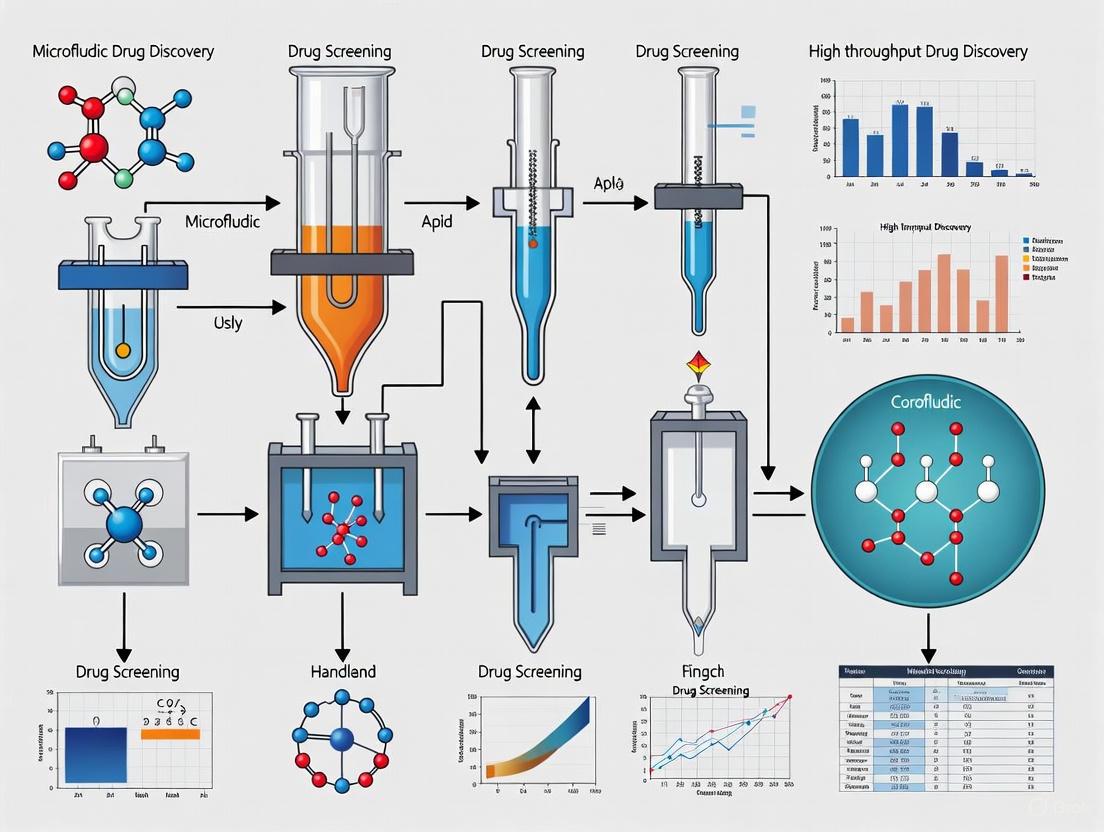

Diagram Title: High-Throughput Screening Workflow

Materials:

- Microwell Array Chip: A microfluidic device containing a dense array of nanoliter-scale wells.

- Pressure-Based Flow Controller: Provides stable and pulsation-free flow for cell loading (e.g., Fluigent or Elveflow systems) [5] [2].

- Cell Line: Stably transfected with a fluorescent reporter for the target pathway.

- Compound Library: Dissolved in DMSO at a standard concentration.

- Automated Fluid Handling System: For sequential injection of multiple reagents (e.g., Fluigent Aria) [5].

- High-Content Fluorescence Imaging System.

Procedure:

- Chip Priming: Connect the microfluidic chip to the pressure controller. Prime all channels with sterile PBS buffer to remove air bubbles and wet the surfaces [5].

- Cell Seeding: Introduce a homogeneous cell suspension into the chip's inlet reservoir. Use a low, constant pressure to flow cells into the microwells, aiming for single-cell occupancy in each well. Stop flow and allow cells to settle for 15-30 minutes [5].

- Compound Introduction: Use an automated multiplexer to sequentially introduce compounds from the library into the chip. Each compound is perfused through the microwell array at a defined concentration for a set duration [5].

- Incubation: Maintain the chip at 37°C and 5% CO₂ for 24-72 hours to allow for cellular response.

- Staining and Imaging: Introduce a fluorescent viability or apoptosis stain (e.g., Calcein-AM / Propidium Iodide) into the chip. After incubation, acquire high-resolution images of each microwell using an automated microscope [3].

- Data Analysis: Quantify fluorescence intensity per well using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, CellProfiler). Normalize data to positive and negative controls. Compounds showing significant activity above a defined threshold are identified as "hits."

Protocol 2: Generating Liposomal Nanoparticles via a Microfluidic Mixer

This protocol details the synthesis of monodisperse lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for drug delivery using a hydrodynamic flow-focusing device.

Workflow Overview:

Diagram Title: LNP Synthesis via Flow-Focusing

Materials:

- Microfluidic Mixer Chip: A chip with a flow-focusing or T-junction geometry.

- Precision Syringe Pumps or Pressure Controllers: Critical for maintaining stable flow rates of the aqueous and organic phases to ensure monodisperse particle size [1] [5].

- Lipids: e.g., DSPC, Cholesterol, PEG-lipid.

- Hydration Buffer: e.g., 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4.

- Dialysis Tubing.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the lipid mixture in pharmaceutical-grade ethanol at a concentration of 5-20 mg/mL. Prepare the aqueous buffer and filter both solutions through a 0.22 µm membrane.

- System Setup: Load the lipid and aqueous solutions into separate syringes. Connect the syringes to the chip inlets via tubing. Place a collection tube at the outlet.

- Particle Generation: Simultaneously inject the lipid (organic) and aqueous solutions into the chip. The flow-focusing geometry hydrodynamically focuses the organic stream, causing rapid mixing and lipid precipitation, forming nanoparticles. The flow rate ratio (aqueous:organic) is the key parameter controlling size and polydispersity. A typical total flow rate is 1-10 mL/min [1].

- Collection and Dialysis: Collect the nanoparticle suspension from the outlet. Transfer to dialysis tubing and dialyze against a large volume of hydration buffer for 12-24 hours to remove ethanol.

- Characterization: Analyze the final LNP preparation for size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering. Encapsulation efficiency can be determined using a method like HPLC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and reagents commonly used in microfluidic drug discovery applications.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microfluidic Drug Discovery

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | Elastomeric polymer for rapid prototyping of microfluidic chips via soft lithography [3]. | Biocompatible, gas-permeable, but can absorb small hydrophobic molecules [3]. |

| iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes | Patient-specific cells for creating physiologically relevant Heart-on-Chip models and personalized drug testing [3]. | Requires rigorous characterization of maturity and electrophysiological functionality [3]. |

| Extracellular Matrix Hydrogels | (e.g., Matrigel, Collagen, Fibrin) Provide a 3D scaffold for cell culture in Organ-on-Chip devices, mimicking the in vivo microenvironment [3]. | Batch-to-batch variability; polymerization conditions must be optimized for microchannels. |

| Fluorescent Calcium Indicators | (e.g., Fluo-4, Fura-2) Used for real-time monitoring of electrophysiology and calcium handling in heart-on-chip models [3]. | Dye loading concentration and incubation time must be optimized to avoid cytotoxicity. |

| Pressure-Based Flow Controllers | Provide stable, pulsation-free fluid delivery for cell culture perfusion, reagent introduction, and droplet generation [5] [2]. | Superior flow stability and responsiveness compared to syringe pumps for many applications [5]. |

| Lipid Mixtures | (e.g., DSPC, Cholesterol, PEG-lipid) Raw materials for the synthesis of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for drug encapsulation and delivery [1]. | Purity and composition directly impact LNP stability, size, and encapsulation efficiency [1]. |

In the pursuit of accelerating drug discovery, microfluidic technology has emerged as a transformative platform, enabling high-throughput screening (HTS) with unprecedented precision and efficiency. The physical behavior of fluids at the microscale fundamentally differs from macroscale phenomena, governed by unique principles that can be harnessed to create highly controlled microenvironments. This application note details three key physical principles—laminar flow, diffusion, and capillary action—that underpin the design and operation of microfluidic devices for drug discovery research. We provide experimental protocols, quantitative data summaries, and practical guidance to enable researchers to leverage these phenomena for advanced screening applications, with a specific focus on generating precise concentration gradients for cytotoxicity assays.

Core Physical Principles and Their Manipulation

Laminar Flow

In microfluidic systems, the flow of fluids is typically laminar rather than turbulent. In laminar flow, fluid moves in parallel, steady layers with no disruption between them [6]. This phenomenon arises from the low Reynolds number (Re), a dimensionless parameter that represents the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces [6]. For microchannels, Re is usually far below 2000, the threshold below which flow remains laminar [6].

- Key Application: Laminar flow allows for the precise manipulation of fluid streams without turbulent mixing. This is exploited in gradient generators to create defined, stable concentration profiles of drugs or test compounds by controlling the volumetric merging of adjacent fluid streams [7]. A recent study utilized this principle to achieve stable gradient generation within 30 seconds for high-throughput cancer drug screening [7].

Diffusion

Diffusion is the process by which molecules move from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration due to random thermal motion [8]. In microfluidic systems, it is the primary mechanism for molecular mixing when two or more fluid streams are brought into contact. The rate of diffusion is significantly influenced by the diffusion coefficient of the molecule and the interfacial contact area between fluid streams [8].

- Key Application: In drug screening, diffusion governs the transport of drug molecules from flow channels into 3D cell cultures or tissue constructs within organ-on-a-chip devices, more accurately mimicking the physiological delivery of therapeutics in vivo [9] [10]. This enables more physiologically relevant assessment of drug efficacy and toxicity compared to static well-plate assays.

Capillary Action

Capillary action, or capillarity, is the ability of a liquid to flow in narrow spaces without the assistance of, or even against, external forces like gravity [11]. This spontaneous wicking is driven by the interplay between cohesive forces (within the liquid) and adhesive forces (between the liquid and the channel walls) [11] [12]. The strength of capillary flow is inversely related to the channel diameter.

- Key Application: Capillary action is the driving force in passive microfluidic systems, such as lateral flow assays and paper-based microfluidic devices [6]. This enables the development of simple, pump-free, and portable diagnostic and screening tools, reducing the need for complex and expensive external instrumentation [6].

Table 1: Quantitative Summary of Key Physical Parameters at the Microscale

| Physical Principle | Governing Parameter | Typical Value/Formula | Impact on Drug Screening Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laminar Flow | Reynolds Number (Re) | ( Re = \frac{\rho v D}{\mu} ) [6]Where ( \rho )=density, ( v )=velocity, ( D )=characteristic diameter, ( \mu )=viscosity.Re < 2000 for laminar flow. | Enables precise fluid stream control and stable gradient generation for high-throughput dose-response studies [7]. |

| Diffusion | Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Varies by molecule and medium.e.g., Small molecules in water: ~10⁻⁹ m²/s.Governs mixing and interstitial transport. | Critical for nutrient and drug delivery in 3D cell cultures; can be a rate-limiting step in organ-on-a-chip models [9]. |

| Capillary Action | Capillary Pressure (Pc) | ( P_c = \frac{2\gamma \cos\theta}{r} ) [12]Where ( \gamma )=surface tension, ( \theta )=contact angle, ( r )=pore radius. | Eliminates the need for pumps in passive devices, simplifying design and reducing costs for point-of-care test applications [6]. |

Experimental Protocol: Generating a Drug Concentration Gradient for High-Throughput Screening

This protocol details the use of a laminar flow-based microfluidic concentration gradient generator (MCGG) for high-throughput drug cytotoxicity screening, adaptable for 96-well plate formats [7].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Microfluidic Gradient Generation

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle Olefin Polymer (COP) | Substrate for device fabrication; offers high optical clarity and low autofluorescence. | Preferred for high-throughput screening due to excellent biocompatibility and optical properties for imaging [7]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Elastomeric material for device fabrication; gas-permeable, biocompatible, and flexible. | Requires plasma oxidation or surface coating (e.g., fibronectin) to render it hydrophilic for improved cell adhesion [9]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) Solution | Model protein solution for validating gradient generation and device performance. | Used in initial device calibration to confirm concentration profile accuracy without consuming expensive drug compounds [7]. |

| Drug Stock Solutions | Compounds for screening (e.g., chemotherapeutic agents). | Prepare in appropriate solvent (e.g., DMSO) and dilute in cell culture medium immediately before use, ensuring final solvent concentration is non-cytotoxic. |

| Cell Culture Medium | Supports cell viability during the assay. | Must be sterile and compatible with the microfluidic device material to prevent bubble formation and nonspecific adsorption. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Device Priming: Connect the outlet of the microfluidic MCGG device to a syringe pump via sterile tubing. Slowly prime all channels with 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or serum-free culture medium to remove air bubbles and wet the channel surfaces. Ensure all waste reservoirs are empty.

Gradient Generation & Validation:

- Prepare two input solutions: Reservoir A containing the drug dissolved in cell culture medium, and Reservoir B containing medium only.

- Load these solutions into their respective input syringes. Initiate flow using the syringe pump at a constant, low flow rate (e.g., 5-50 µL/min) to establish laminar flow conditions [7].

- To validate the gradient, first run the device with a BSA solution in Reservoir A and PBS in Reservoir B. Collect output from different gradient channels and measure the BSA concentration (e.g., via spectrophotometry) to confirm it matches the theoretical profile.

Cell Exposure & On-Chip Incubation:

- Seed the output microchambers or a connected 96-well plate with the target cancer cells (e.g., HCT116 colorectal carcinoma cells) at a standardized density and allow them to adhere overnight in a CO₂ incubator.

- Connect the primed and validated MCGG device to the cell culture platform. Run the drug and medium streams to expose the cells to the generated concentration gradient for a predetermined period (e.g., 24-72 hours).

Viability Assessment & Analysis:

- After exposure, carefully aspirate the medium from the output chambers.

- Add a cell viability indicator (e.g., AlamarBlue or MTT reagent) diluted in fresh medium to the cells.

- Incubate according to the reagent manufacturer's instructions and measure the fluorescence or absorbance.

- Plot cell viability against drug concentration to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) value for the tested drug.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this protocol:

Diagram 1: High-Throughput Drug Screening Workflow

Device Design and Operational Considerations

The physical principles dictate specific design choices. The relationship between channel geometry and the dominant physical phenomena is critical for robust device operation.

Diagram 2: From Principle to Design

The deliberate application of laminar flow, diffusion, and capillary action provides the foundation for sophisticated, high-throughput microfluidic drug screening platforms. Laminar flow enables the generation of precise and stable concentration gradients, diffusion governs physiologically relevant molecular transport in 3D cellular microenvironments, and capillary action facilitates the development of simple, passive devices. By integrating these principles into device design and experimental protocols as outlined, researchers can significantly enhance the efficiency, predictive power, and translational potential of their drug discovery pipeline.

The Evolution from Manual Methods to Automated High-Throughput Systems

The trajectory of drug discovery has been fundamentally reshaped by the transition from manual, low-capacity laboratory techniques to sophisticated, automated high-throughput systems. This evolution began to take shape in the late 20th century, revolutionizing traditional methods that were labor-intensive and time-consuming, often limited to processing just 20–50 compounds per week per laboratory [13] [14]. The driving force behind this transformation was the advent of recombinant DNA technology, which provided access to novel therapeutic targets that existing screening methods were inadequate to address [14]. This technological singularity created the essential conditions for high-throughput screening (HTS) to emerge as a practical solution for rapidly testing hundreds of thousands of compounds against new biological targets [14].

The paradigm has further advanced with the integration of microfluidic technologies, which represent a significant leap in miniaturization and automation. These systems enable unprecedented precision in fluid handling and environmental control while reducing reagent consumption by up to 150-fold compared to conventional well-plate formats [15]. This application note examines the key technological milestones in this evolution, with a specific focus on microfluidic platforms that now enable high-content screening at scales previously unattainable, providing researchers with powerful tools for accelerating therapeutic development.

Technological Milestones in Automation and Miniaturization

The Genesis of High-Throughput Screening

The earliest HTS systems emerged in the mid-1980s, with pioneering work at Pfizer demonstrating a radical departure from traditional screening methods. The initial system, operational by 1986, substituted fermentation broths with dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) solutions of synthetic compounds, utilizing 96-well plates and reduced assay volumes of 50-100μl [14]. This approach dramatically increased screening capacity from approximately 20-50 compounds per week per lab to over 7,000 compounds weekly by 1989 [14]. The transition from single tubes to array formats and from dry compounds requiring custom solubilization to pre-plated compound libraries in DMSO established the fundamental framework upon which all subsequent HTS technologies have been built [14].

Progression to Ultra-High-Throughput Systems

The relentless drive for greater throughput and efficiency has propelled continual innovation in HTS platforms, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Evolution of HTS Throughput and Miniaturization

| Era | Format | Typical Volume | Throughput (compounds/day) | Key Enabling Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-HTS (1980s) | Single test tubes | ~1 mL | 20-50 | Manual pipetting, spectrophotometers [14] |

| Early HTS (1990s) | 96-well plates | 50-100 μL | 1,000-10,000 | Robotic liquid handlers, plate readers [14] |

| Standard HTS (2000s) | 384-well plates | 5-50 μL | 10,000-100,000 | Automated plate handlers, advanced detection systems [16] |

| Ultra-HTS (2010s+) | 1536-well plates | 1-2 μL | >300,000 | Acoustic dispensing, microfluidics [16] |

| Microfluidic HCS (Recent) | Microfluidic chambers | <1 μL (picoliter-nanoliter scale) | Varies (10,000+ individual cell experiments/device) | Integrated membrane valves, soft lithography [15] |

This progression has been characterized by exponential increases in processing capability alongside dramatic reductions in reagent consumption. The emergence of ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) pushed throughput to over 300,000 compounds daily, while microfluidic platforms have enabled screening at unprecedented levels of miniaturization, reducing reagent volumes to the picoliter range [17] [16].

Microfluidic Platforms for High-Throughput Screening

Active-Matrix Digital Microfluidics (AM-DMF)

A transformative advancement in liquid handling, Active-Matrix Digital Microfluidics (AM-DMF) leverages semiconductor-derived electrode arrays to dynamically control thousands of micrometre-scale droplets [17]. This technology enables various programmable operations—including droplet generation, transport, mixing, and dilution—with unparalleled accuracy [17]. Unlike continuous-flow microfluidics, AM-DMF manipulates discrete droplets on a surface without channels, allowing for precise individual control of each droplet's trajectory and processing. The architecture has evolved through several generations: from passive-matrix (DMF 1.0) to active-matrix (DMF 2.0), gate-on-array (DMF 2.5), and finally to integrated circuit-driven (DMF 3.0) systems, each iteration enhancing scalability and control precision [17]. This platform is particularly valuable for applications requiring high-throughput manipulation of precious samples, such as single-cell analysis, genomics, and drug screening [17].

Microfluidic High-Content Cell Screening (HCS)

Microfluidic technology has extended beyond traditional compound screening to enable high-content screening (HCS) with single-cell resolution. These platforms integrate all aspects of cellular experimentation—including cell culture, stimulation, staining, and imaging—within a single miniaturized device [15]. A representative device design fabricated from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) incorporates 32 separate compartments linked to multiple inlets and outlets, with fluid flow controlled by a manifold of integrated membrane valves [15]. In a typical experiment, approximately 300 cells are loaded into each compartment, enabling nearly 10,000 individual cell experiments in a single device [15]. This platform allows researchers to expose different compartments to varying combinations or concentrations of exogenously added factors for different durations, followed by fixation, immunochemical staining, and automated imaging [15].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Microfluidic HCS

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Device Material | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Biocompatible, optically transparent elastomer for device fabrication [15] |

| Cell Culture Substrate | Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Proteins (e.g., Collagen, Fibronectin) | Surface coating to promote cell adhesion and mimic physiological environment [18] |

| Staining Reagents | Fluorophore-conjugated Antibodies, DNA Dyes (e.g., DAPI), Cell Viability Indicators (e.g., Calcein-AM) | Immunocytochemical staining for protein localization and concentration; assessment of cell viability and structure [15] |

| Fixation Reagent | Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative to preserve cellular architecture and protein localization prior to staining [15] |

| Signal Detection Probes | Specific Antibodies, In Situ Hybridization Probes | Primary readouts for localization and concentration of signaling proteins or mRNA [15] |

Protocol: Implementing a Microfluidic HCS Assay for Cell Signaling Analysis

Device Preparation and Cell Loading

- Device Priming: Flush all microfluidic channels with a biocompatible buffer, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), to remove air bubbles and condition the surface.

- Surface Coating (Optional): For adherent cells, introduce an appropriate extracellular matrix protein solution (e.g., collagen or fibronectin at 10-100 μg/mL concentration) into the device and incubate for 1-2 hours at 37°C to promote cell adhesion [18].

- Cell Suspension Preparation: Trypsinize and resuspend adherent cells in appropriate culture medium to a final density of 5-10 × 10^6 cells/mL. The optimal density must be determined empirically to achieve approximately 300 cells per compartment [15].

- Cell Loading: Introduce the cell suspension into the device's main inlet channel using a precision syringe pump or pneumatic pressure system. Actuate membrane valves to partition and isolate individual compartments, trapping cells within each experimental unit [15].

- Cell Adhesion Period: Allow the device to remain under static conditions in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 4-24 hours to enable cell attachment and stabilization.

Compound Handling and Stimulation

- Compound Library Preparation: Prepare solutions of compounds or biological agents in assay-compatible medium at 100-1000× the desired final concentration, accounting for the high dilution factor within the microfluidic device.

- Automated Stimulation: Using the integrated valve control system, program the device to expose each compartment to different combinations or concentrations of stimulants (e.g., receptor ligands, cytokines, or small molecule inhibitors). The system can deliver these stimuli in various patterns—including step changes, concentration gradients, or complex temporal pulses—to mimic physiological or pharmacological conditions [15].

- Incubation: Maintain the device at 37°C, 5% CO2 for the prescribed stimulation period, which can range from minutes for early signaling events to hours or days for longer-term responses.

Fixation, Staining, and Imaging

- Fixation: Introduce a fixative solution (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS) into the device and incubate for 15-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization and Blocking: Flush the device with a permeabilization/blocking buffer (e.g., PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1-5% bovine serum albumin) to permeabilize cell membranes and reduce non-specific antibody binding.

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Introduce primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Follow with multiple wash steps, then introduce fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies and counterstains (e.g., DAPI for nuclei, phalloidin for actin) for 1-hour incubation [15].

- Automated Imaging: Mount the device on a motorized microscope or high-content fluorescence scanner. Acquire images of each compartment using appropriate fluorescence filter sets for each channel. The high cell number per condition (typically hundreds of cells) enables robust statistical analysis of cellular responses [15].

Data Analysis and Hit Identification

- Image Analysis: Utilize automated image analysis software to extract quantitative features from each cell, including subcellular protein localization and concentration, cell shape and size, and other morphological parameters.

- Statistical Comparison: Compare the distributions of these readouts across hundreds of cells exposed to the same experimental condition to identify statistically significant differences between treatment groups.

- Hit Selection: Apply appropriate statistical thresholds (e.g., Z-score > 3 or p-value < 0.01) to identify compounds or conditions that produce biologically significant effects, while controlling for false positives using methods such as p-value distribution analysis (PVDA) [19].

Quantitative HTS Data Analysis Considerations

The transition to quantitative HTS (qHTS), which generates full concentration-response curves for thousands of compounds simultaneously, presents significant statistical challenges [20]. The Hill equation (HEQN) remains the most widely used nonlinear model for describing qHTS response profiles, estimating parameters including baseline response (E0), maximal response (E∞), half-maximal activity concentration (AC50), and shape parameter (h) [20]. However, parameter estimation—particularly for AC50—is highly variable when the tested concentration range fails to include at least one of the two HEQN asymptotes [20]. Statistical simulations demonstrate that AC50 estimates can span several orders of magnitude when assay conditions are suboptimal, emphasizing the critical importance of appropriate study design and the potential need for alternative approaches to characterize concentration-response relationships [20].

The evolution from manual methods to automated high-throughput systems represents a fundamental paradigm shift in biomedical research and drug discovery. This journey—from processing dozens of compounds weekly in individual test tubes to manipulating thousands of droplets in parallel on microfluidic chips—has dramatically accelerated the pace of therapeutic development [13] [14] [17]. Microfluidic platforms, including AM-DMF and integrated HCS devices, now provide unprecedented capabilities for miniaturization, environmental control, and single-cell resolution [17] [15]. These technologies enable researchers to conduct sophisticated experiments with massive reductions in reagent consumption and cellular material requirements, making previously prohibitive screening campaigns both feasible and cost-effective [15]. As these systems continue to evolve, incorporating advances in artificial intelligence, sensor integration, and material science, they will further empower researchers to tackle increasingly complex biological questions and accelerate the delivery of novel therapeutics to patients.

Application Notes

The adoption of microfluidic technologies in high-throughput drug discovery is driven by three core advantages: miniaturization, significantly reduced reagent consumption, and enhanced precision in controlling the cellular and chemical microenvironment. These features directly address major inefficiencies in traditional drug screening, offering a more predictive and cost-effective preclinical research model [21] [22].

Miniaturization for High-Throughput Screening

Miniaturization via lab-on-a-chip (LoC) and droplet microfluidic platforms enables a massive increase in experimental throughput. These systems transform benchtop procedures into microscale, parallelized operations, allowing researchers to screen thousands to millions of compounds or cellular samples in a single, automated run [23] [21]. This is crucial for exploring vast chemical and biological spaces in early drug discovery.

Key Quantitative Impacts of Miniaturization: Table: Throughput and Scale Comparison of Screening Platforms

| Screening Platform | Assay Volume | Throughput | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Microtiter Plate | Microliter to milliliter [24] | ~10^3-10^4 clones per campaign [25] | Standard low-throughput screening |

| Droplet Microfluidics | Femtoliter to nanoliter droplets [21] [25] | >300,000 clones in a single experiment [21] | Ultrahigh-throughput enzyme and antibody screening |

| Integrated LoC Systems | Nanoliter-scale chambers [23] | >10,000 high-resolution images in under one hour [21] | High-content cellular analysis and functional readouts |

Drastic Reduction in Reagent and Sample Consumption

The core benefit of reduced volumes is a dramatic decrease in reagent costs and the consumption of precious samples, such as patient-derived cells or novel chemical compounds. Assays performed in picoliter or nanoliter droplets instead of microliter wells can reduce reagent consumption by orders of magnitude [21]. This miniaturization makes large-scale screening campaigns economically viable and enables more research with limited biological samples.

Key Quantitative Impacts of Reagent Reduction: Table: Economic and Practical Benefits of Volume Reduction

| Parameter | Traditional Workflow | Microfluidic Workflow | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reagent Cost per Assay | High (microliter/milliliter scale) | >1000-fold reduction (nanoliter/picoliter scale) [21] | Enables large-scale screening within budget constraints |

| Sample Requirement | Large volumes | Minimal cell numbers or compound mass | Facilitates work with patient-derived and primary cells [22] |

| Waste Generation | Significant | Minimal | Reduces environmental and disposal costs |

Enhanced Precision and Control

Microfluidic devices provide unparalleled precision in controlling the cellular and chemical microenvironment. Key principles like laminar flow and diffusion-based mixing allow for the generation of highly stable concentration gradients and the precise manipulation of cells [23]. This level of control is fundamental for creating physiologically relevant models and obtaining high-quality, reproducible data.

Key Areas of Enhanced Precision:

- Concentration Gradients: Microfluidic gradient generators enable simultaneous testing of multiple drug concentrations on a single chip with high fidelity, rapidly identifying optimal therapeutic doses [21].

- Tissue-Specific Microenvironments: Organs-on-chips (OoCs) use microfluidic flow and 3D architectures to replicate tissue-specific mechanics and cellular interactions, improving the physiological relevance of toxicity and efficacy testing [23] [22].

- Single-Cell Analysis: Droplet-based encapsulation creates millions of isolated picoliter reactors, enabling functional readouts and screening at the single-cell level with high resolution [21] [25].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ultrahigh-Throughput Screening of Enzyme Libraries via Droplet Microfluidics

This protocol describes an activity-based screen of a metagenomic ketoreductase (KRED) library using droplet microfluidics and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Droplet-Based Enzyme Screening

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrate | Enzyme activity reporter; fluorescence increases upon reaction. | e.g., alcohol 3 [25] |

| Cofactor | Essential for enzymatic redox reaction. | NAD+ or NADP+ [25] |

| Water-in-Oil (w/o) Emulsion Reagents | Creates stable, monodisperse aqueous droplets in a continuous oil phase. | Surfactants and oil for droplet generation and stability [25] |

| Cell Lysis Reagents | Releases intracellular enzymes for activity assay. | Benzonase and lysozyme [25] |

| Culture Media | Supports cell growth and protein expression. | ZY autoinduction medium [25] |

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

Library Preparation and Induction

- Transform an E. coli metagenomic library for expression of KRED variants.

- Grow clones in ZY autoinduction medium to express the enzymes.

Droplet Generation and Incubation

- Resuspend the cell library in a buffer containing the fluorogenic alcohol substrate (e.g., 1 mM alcohol 3) and necessary cofactors.

- Use a microfluidic flow-focusing device to encapsulate single cells into water-in-oil droplets with an average occupancy of 0.1 cells/droplet. The final assay volume is in the picoliter range (e.g., 660 pL) [21] [25].

- Collect the emulsion and incubate for 48 hours at 30°C with orbital shaking (100 rpm) for enzyme expression and reaction.

Droplet Analysis and Sorting

- After incubation, re-emulsify the primary w/o emulsion into a water-in-oil-in-water (w/o/w) double emulsion compatible with FACS.

- Analyze and sort the droplets using a flow cytometer equipped with a 405 nm laser and a 525/50 nm emission filter.

- Set a fluorescence threshold to identify and sort droplets containing active KRED enzymes.

Hit Recovery and Validation

- Collect sorted droplets into growth media, break the emulsion, and plate the cells on LB agar plates.

- After growth, pick colonies and re-assay for activity in a 96-well plate format to confirm hits.

- Sequence plasmids from validated hits to identify novel KRED genes.

Protocol 2: High-Content Drug Screening on a Cartilage-on-Chip Platform

This protocol uses a microfluidic chip with an integrated gradient generator and parallel culture chambers for high-fidelity dose-response studies on tissue models [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Organ-on-Chip Drug Screening

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Chondrocytes or Cell Line | Primary cells or cell line representing the target tissue. | Primary chondrocytes for cartilage modeling [21] |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Hydrogel | Provides a 3D, physiologically relevant scaffold for cell culture. | Collagen, Matrigel, or alginate [22] |

| Drug Solution | The therapeutic compound for testing. | e.g., Resveratrol [21] |

| Culture Media | Maintains cell viability and function during the experiment. | Standard media supplemented as required. |

| Cell Viability/Cell Death Stains | Enables quantitative assessment of drug efficacy and toxicity. | e.g., Live/Dead assay kits [22] |

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

Device Priming and Cell Loading

- Sterilize the polycarbonate or PDMS microfluidic device. To minimize small molecule absorption, consider using alternative polymers like polycarbonate [22].

- Prepare a suspension of chondrocytes in an ECM hydrogel precursor (e.g., GelMA).

- Load the cell-laden hydrogel into the parallel culture chambers of the chip and crosslink to form a stable 3D tissue construct.

Concentration Gradient Generation and Drug Perfusion

- Prepare a stock solution of the drug candidate (e.g., Resveratrol).

- Use the integrated microfluidic gradient generator to create a linear dilution of the drug stock, producing a range of concentrations that are simultaneously perfused through the parallel culture chambers.

- Maintain dynamic flow using a syringe or peristaltic pump to perfuse the drug gradients and fresh media through the cultures for the desired duration (e.g., 72 hours), mimicking physiological shear stress.

Functional Readouts and Analysis

- High-Content Imaging: After treatment, perform live/dead staining and acquire high-resolution images of each chamber using an automated microscope. Quantify cell viability and morphology for each drug concentration.

- Biochemical Analysis: Extract RNA or proteins from the on-chip cultures for transcriptomic or proteomic profiling to understand drug response mechanisms [21].

- Data Integration: Integrate viability and 'omics data to identify the optimal scaffold-doping dose or the IC50 value of the drug, providing a dose-response profile that closely reflects human physiology.

Market Landscape and Growth Projections for Pharma and Biotech Applications

The global microfluidics market is demonstrating robust growth, driven by its increasing adoption in pharmaceutical and biotechnology research. This technology, which involves manipulating small fluid volumes within microscale channels, is revolutionizing drug discovery and development by enabling high-throughput screening with unparalleled precision and efficiency. [23] [26]

Market analyses project a consistent upward trajectory. The market was valued between USD 21.36 billion and USD 22.43 billion in 2024 and is expected to advance at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.8% to 15.5%, culminating in a projected value of USD 32.67 billion to USD 65.9 billion by 2029-2032. This growth is fueled by the rising demand for point-of-care diagnostics, increased need for efficient sample analysis, and continuous technological innovations. [26] [27]

Table 1: Global Microfluidics Market Size Projection (2022-2032)

| Year | Market Size (USD Billion) |

|---|---|

| 2022 | 19.3 |

| 2023 | 21.9 |

| 2024 | 24.5 |

| 2025 | 28.6 |

| 2026 | 32.9 |

| 2027 | 36.8 |

| 2028 | 39.8 |

| 2029 | 45.0+ |

| 2030 | 50.5 |

| 2031 | 57.2 |

| 2032 | 65.9 |

The broader pharmaceutical context shows that 75% of global life sciences executives express optimism about 2025, with 68% anticipating revenue increases and 57% predicting margin expansions. This optimism persists despite industry challenges, including pricing pressures and a significant patent cliff threatening over USD 300 billion in sales through 2030. [28]

Key Market Segments and Applications

Product and Material Segmentation

Microfluidic components account for the largest market share, with microfluidic chips leading this segment. These chips, which form the core of microfluidic systems, are miniaturized devices with etched channels and chambers that precisely control fluid volumes ranging from microliters to nanoliters. [27]

Table 2: Microfluidics Market by Material Type (2024)

| Material | Market Share | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | 49% | Flexible, biocompatible, oxygen permeable, easy fabrication |

| Glass | 27% | Excellent optical clarity, chemical resistance, high precision |

| Silicon | 18% | High precision, durable, suitable for complex architectures |

| Other Materials | 6% | Includes polymers, paper, and hybrid composites |

The dominance of PDMS is attributed to its flexibility, biocompatibility, and suitability for rapid prototyping. However, alternative materials like PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate) are gaining traction due to superior optical clarity, chemical resistance, and cost-effectiveness for specific applications. [26] [27]

Application in Pharmaceutical and Biotech Workflows

Microfluidics technology has penetrated multiple facets of pharmaceutical research and development:

Drug Discovery and Screening: Microfluidic devices enable high-throughput screening (HTS) with significantly reduced reagent consumption and experimental time compared to traditional methods like 96-well plates. They facilitate precision dosing and create physiologically relevant microenvironments for cells and tissues, providing more accurate drug efficacy assessments. [1]

Organ-on-Chip Technology: Advanced platforms such as heart-on-chip (HoC) systems replicate human cardiac physiology with remarkable fidelity. These systems incorporate 3D co-cultures of key cardiac cell types (cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts) in spatially designed arrangements, replicating native multicellular architecture and electromechanical coupling properties essential for accurate disease modeling and drug testing. [3]

Drug Delivery Systems: Microfluidics enables the generation of highly stable, uniform, monodispersed drug carrier particles with higher encapsulation efficiency compared to bulk methods. The technology allows precise control over nanoparticle size and composition, crucial for optimizing drug bioavailability and targeted delivery. [1] [29]

Diagnostics and Point-of-Care Testing: Lab-on-a-chip (LOC) devices miniaturize complex laboratory workflows into compact platforms for applications including infectious disease testing, PCR, genetic screening, and multi-analyte detection. Their portability and minimal reagent requirements make them ideal for resource-limited settings. [23]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Heart-on-Chip Platform for Cardiotoxicity Screening

Objective: To establish a reproducible heart-on-chip model for assessing drug-induced cardiotoxicity using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-cardiomyocytes.

Materials:

- PDMS-based microfluidic device with integrated microchannels

- Patient-derived iPSC-cardiomyocytes

- Cardiac fibroblasts and endothelial cells

- Culture medium supplemented with growth factors

- Extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogel (e.g., Matrigel, collagen)

- Real-time biosensors for electrophysiological monitoring

- Test compounds and control articles

Procedure:

- Device Preparation: Fabricate microfluidic devices using soft lithography with PDMS. Sterilize devices using UV irradiation or autoclaving.

- Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Prepare cell suspension containing iPSC-cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, and endothelial cells at a ratio of 70:15:15 in ECM hydrogel.

- Introduce cell-hydrogel mixture into the microfluidic chamber at a density of 20-30 million cells/mL.

- Allow gel polymerization for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Perfuse with culture medium at a flow rate of 0.1-1 μL/s to mimic physiological shear stress.

- Maturation Phase: Maintain the construct under continuous perfusion for 7-14 days to allow tissue maturation and functional synchronization.

- Functional Assessment:

- Monitor contractility using integrated motion sensors or video analysis.

- Record electrophysiological parameters using embedded microelectrodes.

- Measure biomarker secretion (e.g., troponin, BNP) via integrated biosensors.

- Compound Testing:

- Expose tissues to test compounds via perfusion medium.

- Include positive (e.g., doxorubicin for cardiotoxicity) and negative controls.

- Monitor functional parameters continuously for 72 hours.

- Assess viability using calibrated ATP-based assays.

- Data Analysis:

- Quantify changes in beating frequency, contractile force, and conduction velocity.

- Determine IC50 values for functional parameters.

- Compare biomarker release profiles between treatments.

Protocol 2: Microfluidic Synthesis of Drug-Loaded Nanoparticles

Objective: To fabricate uniform, monodispersed drug-loaded lipid nanoparticles using a staggered herringbone micromixer (SHM) design.

Materials:

- PDMS or PMMA microfluidic chip with SHM pattern

- Lipid mixture in ethanol (e.g., POPC, cholesterol, triolein)

- Aqueous phase containing therapeutic agent (e.g., siRNA, small molecule drug)

- Precision syringe pumps with flow rate control

- Collection vial with appropriate buffer

- Dynamic light scattering instrument for size characterization

- HPLC system for encapsulation efficiency analysis

Procedure:

- Device Preparation:

- Fabricate SHM device using soft lithography or hot embossing.

- Condition channels with appropriate solvent prior to use.

- Solution Preparation:

- Prepare lipid solution in ethanol at 10-20 mg/mL concentration.

- Dissolve therapeutic agent in aqueous buffer (e.g., citrate, phosphate) at target concentration.

- System Setup:

- Load lipid solution into glass syringe connected to inlet 1.

- Load aqueous phase into glass syringe connected to inlet 2.

- Mount syringes in precision pumps and connect to microfluidic device.

- Place collection vial at outlet port.

- Nanoparticle Formation:

- Initiate flow with defined flow rate ratio (FRR = 3:1 aqueous-to-organic phase).

- Set total flow rate to 10-20 mL/min initially.

- Collect nanoparticle suspension in vial containing 5x volume of dilution buffer.

- Process Optimization:

- Systematically vary flow rate ratio (1:1 to 5:1) to optimize particle size.

- Adjust total flow rate to control mixing efficiency.

- Modify lipid composition to alter encapsulation properties.

- Characterization:

- Determine particle size and polydispersity index by dynamic light scattering.

- Measure zeta potential using electrophoretic light scattering.

- Quantify drug encapsulation efficiency via HPLC after removal of unencapsulated drug.

- Assess stability over 14 days at 4°C and 25°C.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microfluidic Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | Flexible polymer for device fabrication; biocompatible and oxygen permeable | Organ-on-chip devices, droplet generators, micromixers |

| PMMA (Polymethyl methacrylate) | Rigid polymer with excellent optical clarity; chemical resistant | Microfluidic chips for diagnostics, high-throughput screening devices |

| Extracellular Matrix Hydrogels (Matrigel, collagen) | Provide 3D scaffold for cell culture; mimic in vivo microenvironment | Organ-on-chip models, 3D cell culture, tissue barrier models |

| Lipid Mixtures (POPC, cholesterol, PEG-lipids) | Form self-assembling nanostructures for drug encapsulation | Lipid nanoparticle synthesis, nucleic acid delivery systems |

| Fluorescent Tags and Biosensors | Enable real-time monitoring of cellular responses and analyte detection | High-content screening, metabolic activity assays, biomarker detection |

| Surface Modification Reagents (PLL-g-PEG, silanes) | Modify channel surface properties to control cell adhesion or prevent non-specific binding | Cell patterning, reduction of analyte adsorption, enhanced biocompatibility |

Future Outlook and Strategic Implications

The microfluidics field is positioned for continued expansion and technological advancement. Several emerging trends are likely to shape its future development:

Integration with Artificial Intelligence: AI-driven microfluidics is emerging as a powerful combination, enabling intelligent experimental design, real-time process optimization, and advanced data analysis from high-content screening assays. [23] [28]

Multi-Organ Chip Systems: The development of integrated multi-organ platforms (e.g., heart-liver chips) allows researchers to study systemic drug metabolism and organ-specific toxicity in ways that were previously impossible, addressing critical needs in managing polypharmacy. [3]

Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Digital microfluidics, which uses electric fields to manipulate individual droplets on an open surface, offers a more adaptable platform for clinical diagnostics, potentially enabling rapid testing in resource-limited settings. [27]

Personalized Medicine Applications: The incorporation of patient-derived iPSCs into organ-on-chip platforms enables creation of truly individualized disease models, opening new frontiers for personalized therapeutic testing and precision medicine. [3]

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these market dynamics and mastering the associated experimental protocols is becoming increasingly crucial. The ability to leverage microfluidic technologies effectively will provide significant advantages in accelerating drug discovery pipelines, enhancing predictive accuracy, and ultimately bringing safer, more effective therapies to patients faster.

From Concept to Lab: Implementing Microfluidic Systems for Advanced Screening and Assays

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) has fundamentally transformed the pace and efficiency of therapeutic discovery since its emergence in the mid-1980s, reducing months of manual work to days by enabling the parallel testing of thousands of compounds [30]. By definition, HTS simultaneously analyzes thousands of samples for biological activity at the cellular, pathway, or molecular level, with a screen considered "high throughput" when it conducts over 10,000 assays per day [30]. The primary goal of HTS is to rapidly identify active compounds, proteins, or genes—collectively known as "hits"—that modulate a specific biomolecular pathway [31] [30]. This technique has expanded from its pharmaceutical industry origins into diverse research fields including synthetic biology, tissue engineering, and regenerative medicine [30].

The adoption of miniaturized assay formats such as 1536-well plates, advanced automation, robotics, and sophisticated data analysis tools has been crucial to this evolution [32] [30]. More recently, quantitative HTS (qHTS) has emerged as a powerful advancement, allowing researchers to test compounds across multiple concentrations simultaneously, thereby generating concentration-response data that provides richer information on compound activity and potency [20] [30]. When framed within the context of microfluidic devices for drug discovery, HTS platforms gain enhanced capabilities for manipulating small fluid volumes with high precision, enabling more complex and information-rich experiments [23].

HTS Platform Architectures

HTS platforms integrate multiple components into a cohesive system designed for automated, rapid experimentation. The architecture determines the platform's capabilities, throughput, and suitability for specific applications.

Traditional and Microtiter Plate-Based Systems

Traditional HTS relies heavily on microtiter plate formats and robotic liquid handling systems. The evolution from 96-well to 1536-well plates and beyond has significantly increased throughput while reducing reagent consumption and cost [32] [30]. These systems typically incorporate:

- Automated liquid handlers for precise compound and reagent dispensing

- Robotic plate handlers to transport plates between instruments

- High-sensitivity detectors to capture assay signals [20] [32]

- Environmental controllers to maintain optimal conditions for biological assays

This architecture supports a wide range of assay types, including biochemical, cell-based, and phenotypic screens. However, it faces limitations in reagent consumption, operational complexity for complex assays, and fluid handling precision at very small volumes [32].

Microfluidic and Lab-on-a-Chip Systems

Microfluidics, the science of manipulating small fluid volumes (microliter to picoliter range) within channels less than 1 millimeter wide, enables the development of lab-on-a-chip (LoC) devices that integrate multiple laboratory functions into a single, compact platform [23]. These systems offer several distinct advantages for HTS:

- Minimal reagent and sample consumption

- Faster analysis and processing times

- High precision and reproducibility due to exact fluid control

- Portability and compact design

- Integrated, automated workflows [23]

Key microfluidic architectures for HTS include:

- Continuous-flow chips: Utilize microchannels to move fluids for mixing, separation, and chemical reactions

- Droplet-based microfluidics: Create isolated picoliter compartments for single-cell analysis or digital PCR, enabling ultra-high-throughput screening [23]

- Paper-based microfluidics: Provide low-cost, disposable diagnostic tools suitable for point-of-care testing [23]

- Valved microfluidic chips: Incorporate integrated microvalves to automate and control complex fluidic operations [23]

Active-Matrix Digital Microfluidics (AM-DMF)

A transformative evolution in microfluidics, Active-Matrix Digital Microfluidics (AM-DMF) leverages semiconductor-derived electrode arrays to dynamically control thousands of micrometre-scale droplets independently and in parallel [17]. This architecture represents a significant advancement over conventional microchannel-based systems and earlier passive-matrix approaches.

AM-DMF enables various programmable operations—including droplet generation, transport, mixing, merging, splitting, and dilution—with unparalleled accuracy [17]. The technology has evolved through several generations:

- DMF 1.0 (Passive-Matrix): Early digital microfluidics with limited scalability

- DMF 2.0 (Active-Matrix): Introduced thin-film transistors (TFTs) for enhanced control of larger droplet arrays

- DMF 2.5 (Gate-on-Array): Further improved integration and control capabilities

- DMF 3.0 (Integrated Circuit-Driven): Currently emerging with full integration of driving circuits for highest performance [17]

This progression has been a key driver in advancing the commercialization of microfluidic technology for high-throughput biological applications [17].

Table 1: Comparison of HTS Platform Architectures

| Architecture | Throughput Potential | Volume Range | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plate-Based | 10,000 - 100,000 assays/day [30] | Microliter | Established protocols, compatible with diverse assays | Compound screening, target validation |

| Continuous-Flow Microfluidics | Moderate to High | Nanoliter to Microliter | Precise fluid control, integrated functions | Chemical synthesis, cell analysis [23] |

| Droplet-Based Microfluidics | Very High (kHz rates) | Picoliter | Massive parallelism, single-cell resolution | Single-cell analysis, digital PCR [23] |

| Active-Matrix DMF | High (parallel droplet control) | Nanoliter (e.g., 0.5 nL [17]) | Dynamic reconfigurability, programmability | Genomics, single-cell analysis, diagnostics [17] |

Core HTS Workflows

The HTS process comprises multiple interconnected stages, from initial planning to hit confirmation. Successful implementation requires careful coordination across these phases.

Assay Development and Library Design

The foundation of any HTS campaign lies in robust assay development and strategic library design. The scientific objective must be clearly defined, typically categorized as either optimization (enhancing a target property by tuning material structure or processing) or exploration (mapping a structure-property relationship to build predictive models) [33].

Feature selection involves identifying relevant variables—both intrinsic (e.g., polymer composition, architecture, sequence patterning, molecular weight) and extrinsic (e.g., sample preparation protocols, substrate choice) [33]. For combinatorial libraries, careful consideration of variable discretization (subdividing features into intervals across the desired range) and design space size is crucial for managing experimental complexity [33].

Assay development must address:

- Biological relevance to the target pathway or phenotype

- Robustness and reproducibility under automated conditions

- Compatibility with detection systems and automation platforms

- Signal-to-noise optimization to ensure sufficient window for hit identification [31]

Screening Execution and Hit Identification

The screening phase involves running the actual experiments and identifying candidate hits based on established criteria.

Table 2: Key Steps in HTS Screening Execution

| Step | Description | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Reformating compound libraries into assay-ready plates | Miniaturization (1536-well plates), DMSO tolerance, compound stability [32] [30] |

| Liquid Handling | Transferring compounds, reagents, and cells | Automation, precision (CV < 10%), compatibility with assay volumes |

| Assay Incubation | Allowing biological reaction to proceed | Environmental control (temperature, CO₂, humidity), timing synchronization |

| Signal Detection | Measuring assay endpoint or kinetic reads | Detection modality (luminescence, fluorescence, absorbance), sensitivity, dynamic range |

| Hit Identification | Selecting compounds with significant activity | Statistical criteria (e.g., >3σ from mean), normalization methods (Z-score, B-score) [31] |

In qHTS, concentration-response curves are generated simultaneously for thousands of compounds, typically modeled using the Hill equation (Equation 1) to estimate key parameters like AC₅₀ (concentration for half-maximal response) and E_max (maximal response) [20]:

Where Ri is the measured response at concentration Ci, E₀ is the baseline response, E_∞ is the maximal response, and h is the Hill slope [20].

However, parameter estimates from the Hill equation can be highly variable when the tested concentration range fails to include at least one of the two asymptotes, when responses are heteroscedastic, or when concentration spacing is suboptimal [20]. False positives and false negatives remain significant challenges, as truly null compounds may appear active due to random variation, while truly active compounds with "flat" profiles may be missed [20].

HTS Data Analysis and Hit Validation

Data analysis transforms raw screening data into meaningful biological insights. The process involves multiple quality control steps to address systematic variation inherent in automated screening processes [31].

Traditional plate controls-based and non-controls-based statistical methods have been widely used for HTS data processing and active identification [31]. More recently, improved robust statistical methods have been introduced to reduce the impact of systematic row/column effects, though these can sometimes be misleading and result in more false positives or false negatives if applied inappropriately [31].

A recommended three-step statistical decision methodology includes:

- Determining the most appropriate HTS data-processing method and establishing criteria for quality control review from assay signal window and DMSO validation tests

- Performing a multilevel statistical and graphical review of screening data to exclude results outside quality control criteria

- Applying the established active criterion to quality-assured data to identify active compounds [31]

Secondary screening provides critical hit validation through more physiologically relevant models, including:

- Cell-based assays for cellular activity and selectivity

- ADMET assays (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity) for preliminary pharmacokinetic assessment

- Biophysical assays to confirm direct target engagement [30]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantitative HTS (qHTS) with Concentration-Response Analysis

This protocol describes the process for running a qHTS campaign and analyzing the resulting concentration-response data [20].

Materials and Reagents

- Compound library (typically 10,000-100,000 compounds)

- Assay reagents specific to biological target

- Cell line (if cell-based assay)

- Solvent controls (DMSO, buffer)

- Reference controls (positive/negative)

Procedure

- Assay Preparation

- Format compound library in 1536-well plates using acoustic dispensing or pintool transfer

- Include control wells (16-32 wells/plate) for background, positive control, and negative control

- Use concentration ranges spanning at least 4 orders of magnitude (e.g., 1 nM - 100 µM)

Compound Transfer

- Employ non-contact dispensing for compound addition to minimize carryover

- Maintain consistent DMSO concentration across all wells (typically <1%)

- Include randomization schemes to mitigate plate position effects

Assay Incubation and Readout

- Incubate plates under appropriate environmental conditions

- Measure endpoint or kinetic signals using plate readers

- Record raw data for subsequent analysis

Data Normalization

- Normalize raw data using plate-based controls:

- Apply correction algorithms (B-score, Z-score) to remove systematic row/column effects [31]

Curve Fitting and Parameter Estimation

- Fit normalized concentration-response data to Hill equation (Equation 1)

- Estimate key parameters: AC₅₀, E_max, Hill slope (h), and baseline (E₀)

- Assess curve fit quality using R² or similar goodness-of-fit metrics

Hit Classification

- Classify compounds based on curve shape and efficacy

- Prioritize full agonists/antagonists with well-defined AC₅₀ values

- Exclude promiscuous inhibitors and cytotoxic compounds using counter-screens

Troubleshooting Notes

- Poor curve fits often result from inadequate concentration range or insufficient asymptote definition [20]

- AC₅₀ estimates are most reliable when the concentration range defines both upper and lower response levels [20]

- Increasing replicate measurements (n=3-5) significantly improves parameter estimation precision [20]

Protocol 2: Active-Matrix Digital Microfluidics (AM-DMF) for High-Throughput Screening

This protocol describes the use of AM-DMF technology for high-throughput droplet-based screening applications [17].

Materials and Reagents

- AM-DMF device (TFT-based active matrix)

- Aqueous samples (compounds, cells, reagents)

- Immersion oil (filler fluid)

- Surface coatings (e.g., fluorocarbon layers) to reduce fouling

- Cleaning solutions (ethanol, detergents)

Procedure

- Device Preparation

- Clean AM-DMF device surface with appropriate solvents

- Apply hydrophobic and/or antifouling coatings if required

- Fill device with immersion oil to reduce evaporation and facilitate droplet movement

Droplet Generation and Loading

- Dispense nanoliter-scale aqueous samples onto device

- Generate droplets of precise volumes using electrode actuation patterns

- Verify droplet size and consistency through imaging

Droplet Manipulation

- Program electrode activation sequences for droplet transport

- Implement mixing protocols through rapid droplet merging and splitting

- Perform dilution steps using controlled droplet combinations

Assay Execution

- Merge compound, target, and detection reagent droplets

- Incubate for appropriate time with temperature control

- Measure endpoint or kinetic signals using integrated detection

Data Collection and Analysis

- Use integrated sensors (impedance, optical) for real-time monitoring

- Record droplet positions and assay results

- Analyze data using custom or commercial software

Technical Considerations

- Electrode design and driving waveforms significantly impact droplet manipulation reliability [17]

- Integration of sensing capabilities (e.g., impedance, optical) enables real-time droplet tracking and analysis [17]

- Biofouling remains a challenge and requires appropriate surface treatments or device passivation [17]

Visualization of HTS Workflows

HTS Experimental Workflow

HTS Experimental Workflow

Quantitative HTS Data Analysis

Quantitative HTS Data Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Source of chemical diversity for screening | Include diversity-oriented synthesis compounds, natural products, FDA-approved drugs [30] |

| Cell Lines | Biological system for phenotypic or target-based screening | Use engineered lines with reporter constructs for specific pathways; primary cells for physiological relevance |

| Detection Reagents | Generate measurable signals from biological activity | Luminescence for sensitivity, fluorescence for homogeneity, absorbance for cost-effectiveness |

| Assay Kits | Optimized reagent combinations for specific targets | Provide standardized protocols and controls; ensure reproducibility across screens |

| Surface Coatings | Modify substrate properties for cell attachment or reduce fouling | Extracellular matrix proteins for cell-based assays; PEG or fluorocarbon for microfluidics [17] |

| Immersion Oils | Filler fluid for digital microfluidics | Enable droplet actuation; prevent evaporation; must be immiscible with aqueous samples [17] |

High-Throughput Screening platforms have evolved from simple microtiter plate-based systems to sophisticated architectures incorporating microfluidics, automation, and advanced data analytics. The integration of quantitative approaches that generate concentration-response data and miniaturized technologies like active-matrix digital microfluidics is driving increased information content and efficiency in drug discovery.

The future of HTS lies in the continued convergence of biology, engineering, and data science. Artificial intelligence is already being integrated into platforms like AM-DMF to increase the efficiency and reliability of complex workflows [17]. Similarly, 3D cell models and organ-on-chip technologies are providing more physiologically relevant screening environments [23]. As these technologies mature, HTS will continue to transform from a simple hit identification tool to an integrated platform for understanding complex biological systems and advancing personalized medicine.

Concentration Gradient Generators (CGGs) for Rapid, Accurate Dose-Response Studies

Concentration Gradient Generators (CGGs) represent a transformative microfluidic technology that enables the precise generation of concentration gradients for dose-response studies in drug discovery research. Traditional methods for creating drug dilutions, such as manual pipetting and serial dilution, are not only time-consuming and labor-intensive but also prone to cumulative errors, which can significantly affect the determination of key pharmacological parameters like the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) [7]. Microfluidic CGGs address these limitations by leveraging the unique behavior of fluids at the microscale, allowing for the rapid, accurate, and high-throughput creation of concentration gradients [34] [7]. This capability is crucial for applications ranging from high-throughput drug screening and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) to personalized medicine, as it systematically evaluates the optimal concentration of a single drug or the most effective drug combinations [35] [7]. By integrating CGGs with on-chip cell culture arrays, these platforms facilitate automated assay workflows, reduce manual errors, and enhance experimental efficiency, thereby accelerating the drug development process [36].

Theoretical Foundations and Operating Principles

The operation of microfluidic CGGs is governed by the fundamental principles of fluid dynamics at low Reynolds numbers (Re), where laminar flow predominates, and viscous forces far exceed inertial forces [34] [23]. In this regime, fluids flow in parallel streams without turbulence, and mixing occurs primarily through molecular diffusion at the interface between adjacent fluid streams [34].

Two primary types of CGGs have been developed based on their mixing mechanisms:

- Passive CGGs: These generators rely on channel geometry and hydrodynamic resistance to control fluid mixing without external fields. A classic example is the "Christmas tree" design, which uses a network of bifurcating and recombining channels to perform serial dilutions, generating a linear concentration gradient across multiple output channels [34] [37]. The final concentration at each output is determined by the principle of flow resistance, analogous to Ohm's law in electric circuits. The volumetric flow rate (Q) is related to the pressure drop (ΔP) and hydraulic resistance (R) by ΔP = Q × R. By designing channels with specific resistance ratios, the desired flow rate ratios—and thus concentration ratios—can be precisely achieved [37].

- Active CGGs: These systems utilize external physical fields (e.g., magnetic, acoustic, electric) to precisely control fluid mixing, enabling the generation of dynamic and complex (nonlinear) concentration gradients [34]. This allows for more sophisticated simulations of in vivo conditions.

A critical advancement is the development of flowless diffusional μ-CGGs. Unlike conventional systems that require continuous fluid flow, these devices generate shear-free concentration gradients via diffusion alone within a microfluidic grid connecting source and sink reservoirs. This design is particularly beneficial for cell-based assays, as it eliminates shear stress that can influence cellular behavior [36].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Cancer Drug Screening Using a Laminar Flow-Based CGG

This protocol details the use of a pressure-driven CGG for the cytotoxicity assessment of chemotherapeutic agents [7].

Materials and Reagents

- Microfluidic Device: Fabricated from Cycle Olefin Polymer (COP) via hot embossing [7].

- Cell Line: Human bladder cancer cells (T24) [37].

- Drugs of Interest: e.g., Cisplatin, Gemcitabine [37].

- Staining Reagents: Fluorescein for gradient validation; CellTracker Green CMFDA or propidium iodide (PI) for live/dead cell staining [7].

- Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or cell culture medium.

Procedure

- Device Priming: Flush all microchannels with a buffer solution, such as PBS, to remove air bubbles and ensure proper wetting of the channels. Use a syringe pump to maintain a steady flow during this process.

- Gradient Validation: Before cell-based experiments, validate the generated concentration gradient. Introduce a fluorescein solution into the drug inlet and PBS into the buffer inlet. After allowing the gradient to stabilize (typically within 30 seconds [7]), capture the fluorescence profile across the output channels using a fluorescence microscope. Confirm that the measured concentrations conform to the theoretical values (e.g., R² > 0.99 [7]).

- On-Chip Cell Culture: Seed T24 cells embedded in a 3D fibrin gel into the cell culture chambers of the device. Allow the cells to attach and stabilize under a continuous flow of fresh culture medium for 24-48 hours.