Strategies for Enhancing Nanoparticle Structural Stability in Systemic Circulation: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive examination of strategies to improve the structural stability of nanoparticles during systemic circulation, a critical factor for successful drug delivery.

Strategies for Enhancing Nanoparticle Structural Stability in Systemic Circulation: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of strategies to improve the structural stability of nanoparticles during systemic circulation, a critical factor for successful drug delivery. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles governing nanoparticle stability, advanced engineering methodologies, systematic optimization approaches, and rigorous validation techniques. The content synthesizes current scientific understanding with practical applications, addressing key challenges such as protein corona formation, biological barrier navigation, and maintaining colloidal integrity to enhance therapeutic efficacy and safety profiles of nanomedicines.

Understanding Nanoparticle Stability: Fundamental Principles and Circulation Challenges

Defining Nanoparticle Stability in Physiological Environments

For researchers in drug development, defining and ensuring nanoparticle stability in physiological environments is a critical hurdle in translating nanomedicines from the lab to the clinic. Stability here extends beyond simple aggregation resistance; it encompasses the preservation of structural integrity, surface functionality, and therapeutic payload throughout systemic circulation to achieve the desired biodistribution and efficacy. This guide addresses common challenges and provides targeted troubleshooting strategies to improve nanoparticle performance in circulation research.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Troubleshooting Common Stability Issues

This section addresses frequent problems encountered when testing nanoparticles in biological media.

Problem 1: Rapid Aggregation in Physiological Buffers Nanoparticles are stable in pure water but aggregate immediately upon addition to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or cell culture media.

| Possible Cause | Investigation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient steric stabilization | Measure hydrodynamic size & PDI via DLS in water vs. PBS [1]. | Introduce a dense PEG coating to provide steric hindrance [1] [2]. |

| Low surface charge magnitude | Measure zeta potential. A value between -10 mV and +10 mV indicates poor electrostatic stabilization [3]. | Modify surface chemistry to increase charge. Aim for a zeta potential magnitude > 20 mV for moderate stability [3]. |

| Surface protein fouling | Incubate with serum, then re-measure size and zeta potential [1]. | Use higher density or different topology (e.g., cyclic) PEG coatings to better resist protein adsorption [1] [2]. |

Problem 2: Short Systemic Circulation Lifetime Nanoparticles are cleared rapidly from the blood in in vivo models, limiting tumor accumulation.

| Possible Cause | Investigation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein corona formation | Isolate nanoparticles after blood contact and analyze corona composition via proteomics [4]. | Tune nanoparticle elasticity; intermediate elasticity (75-700 kPa) favors adsorption of ApoA1, which correlates with longer circulation [4]. |

| Surface charge is too positive | Measure zeta potential at physiological pH. | Aim for a neutral or slightly negative surface charge to reduce non-specific cellular uptake [1] [5]. |

| Poor stealth coating stability | Use a ligand exchange or encapsulation method that forms a stable, covalent bond with the nanoparticle core (e.g., siloxane bonds) [1]. | Optimize surface chemistry for a dense, stable PEG layer to minimize opsonization and macrophage uptake [1] [6]. |

Problem 3: Loss of Functionality After Surface Modification Targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) lose activity or become masked after conjugation.

| Possible Cause | Investigation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-specific protein adsorption | Test binding to the target antigen in a serum-free buffer vs. serum-containing media. | Use efficient blocking agents (e.g., BSA) and high-density PEG spacers to minimize non-specific binding [7]. |

| Improper conjugation chemistry | Use techniques like FTIR or fluorescence tagging to confirm ligand attachment [1]. | Employ controlled, site-specific conjugation chemistries (e.g., thiol-maleimide) and avoid EDC crosslinking when both amine and carboxyl groups are present to prevent crosslinking [1] [7]. |

| Aggregation during conjugation | Monitor hydrodynamic size before and after each conjugation step [7]. | Optimize the antibody-to-nanoparticle ratio and maintain an optimal pH (often 7-8) during conjugation [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does "nanoparticle stability" truly mean in the context of physiological environments? It is a multi-faceted concept. Beyond just resisting aggregation, it includes [8]:

- Chemical Stability: The core composition and crystal structure must not degrade.

- Surface Stability: The surface chemistry, charge, and conjugated ligands must remain functional and unaltered.

- Functional Stability: The nanoparticle's ability to deliver its payload to the intended target must be preserved throughout its circulation time.

Q2: How can I accurately monitor nanoparticle stability in my experiments? A combination of techniques is essential. The table below outlines key methods.

Table: Key Techniques for Monitoring Nanoparticle Stability

| Technique | What It Measures | Application in Stability Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic diameter and Polydispersity Index (PDI) [9] [3] | Track size increase over time in biological media to monitor aggregation [1] [3]. |

| Zeta Potential | Surface charge and colloidal stability [3] | A stable zeta potential in serum indicates resistance to protein fouling. A shift towards zero suggests instability [1]. |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Optical properties (for plasmonic NPs) [3] | A shift or broadening of the plasmon peak indicates aggregation [2]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Core size, shape, and morphology [3] | Confirm DLS data and visually identify aggregation or changes in core structure [1]. |

Q3: My nanoparticles are stable in PBS but aggregate in cell culture media. Why? Cell culture media contains ions and proteins. ions can neutralize surface charge (reducing electrostatic stabilization), and proteins can adsorb to the surface, bridging particles together. Enhancing steric stabilization with a robust PEG layer is the most effective countermeasure [1] [8].

Q4: How does nanoparticle elasticity influence blood circulation time? A non-monotonic relationship exists. Nanoparticles with intermediate elasticity (e.g., ~75 kPa to 700 kPa) have shown the longest circulation lifetimes. This is because their elasticity influences the composition of the protein corona that forms upon entering the blood, specifically enriching in apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1), which is associated with reduced macrophage uptake and prolonged circulation [4].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Protocol: Engineering Hydrophilic, Functionalized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles

This protocol, based on a published approach, details the creation of nanoparticles with long-term stability in biological media [1].

1. Ligand Exchange with Triethoxysilylpropylsuccinic Anhydride (SAS)

- Starting Material: Begin with oleic acid-coated iron oxide nanoparticles (NP-OA) synthesized via thermal decomposition.

- Reaction: Disperse NP-OA in anhydrous toluene. Add triethoxysilylpropylsuccinic anhydride (SAS) and react under inert atmosphere with stirring.

- Mechanism: The anhydride group of SAS binds to the nanoparticle surface, displacing oleic acid. Concurrently, ethoxysilane groups hydrolyze and condense, forming a cross-linked siloxane network that anchors the coating to the surface.

- Purification: Precipitate the resulting SAS-coated nanoparticles (NP-SAS) and wash with ethanol to remove unreacted species.

2. PEGylation via EDC Coupling

- Reaction: Disperse NP-SAS in MES buffer. Add amine-functionalized PEG (MW = 2,000 Da) and N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) as a coupling agent.

- Mechanism: DCC activates the free carboxyl groups on the NP-SAS surface, enabling the formation of amide bonds with the terminal amines of the PEG chains.

- Purification: Dialyze the final product (NP-SAS-PEG-NH2) extensively against water to remove coupling reagents and unbound PEG.

3. Validation and Stability Assessment

- Confirm Coating: Use FTIR to verify the disappearance of oleic acid peaks and the appearance of characteristic siloxane (~1031 cm⁻¹) and PEG (C-O-C, ~1112 cm⁻¹) bands [1].

- Quantify Functionality: Use a colorimetric assay (e.g., with SPDP) to quantify the number of surface amine groups (approximately 70 per nanoparticle was reported) [1].

- Test Stability: Incubate NP-SAS-PEG-NH2 in PBS, DMEM+10% FBS, and pure FBS. Monitor the hydrodynamic size by DLS for at least 15 days. Stable nanoparticles will show no significant size increase or precipitation [1].

Methodology: Investigating the Elasticity-Protein Corona Relationship

This methodology outlines how to isolate and study the effect of nanoparticle elasticity on protein corona formation and systemic circulation [4].

1. Synthesis of Core-Shell Nanoparticles with Tunable Elasticity

- Core Fabrication: Synthesize hydrogel nanoparticles (nanogels) with varying crosslinking densities (monomer-to-crosslinker ratios) to create cores with different elasticities (e.g., 75 kPa to 1700 kPa). Use bulk hydrogel measurements to assign Young's modulus.

- Shell Formation: Coat all nanogel cores with an identical PEGylated lipid bilayer (e.g., DOPC:DSPE-PEG2000, 90:10 mass ratio) to standardize surface chemistry.

- Characterization: Use Cryo-EM/TEM to confirm core-shell structure and DLS to ensure consistent hydrodynamic size and zeta potential across all samples.

2. In Vitro Protein Corona Analysis

- Incubation: Incubate a standardized amount of each nanoparticle type (differing only in core elasticity) in mouse plasma for a set time (e.g., 1 hour).

- Corona Isolation: Separate the nanoparticle-protein corona complexes from unbound plasma proteins via centrifugation and careful washing.

- Protein Identification and Quantification: Digest the corona proteins and analyze via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Identify and relatively quantify the proteins present.

3. In Vivo Circulation Lifetime Study

- Animal Model: Administer the different nanoparticle formulations to mouse models (e.g., via tail vein injection).

- Pharmacokinetic Sampling: Collect blood samples at multiple time points post-injection.

- Quantification: Measure nanoparticle concentration in blood over time using a relevant technique (e.g., fluorescence, radiolabeling, or elemental analysis for metal cores).

- Correlation: Plot systemic circulation lifetime versus nanoparticle elasticity and correlate with the relative abundance of specific corona proteins (e.g., ApoA1) identified in the in vitro study.

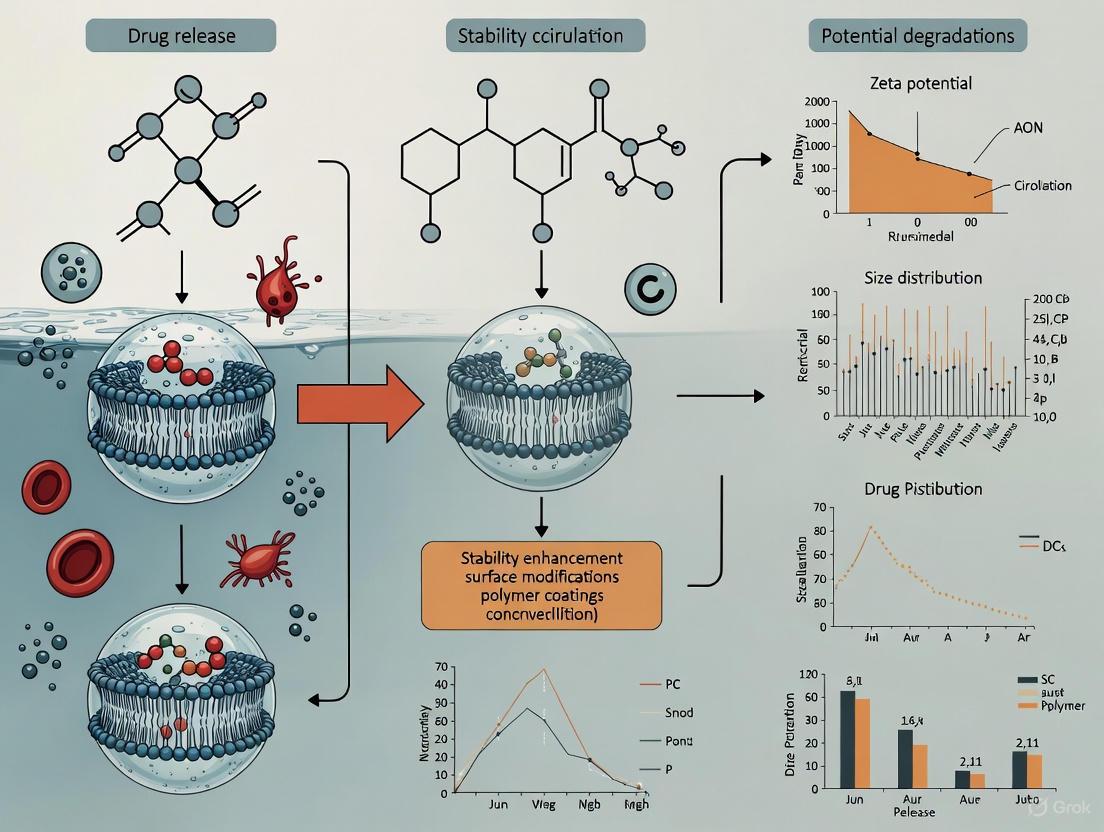

Essential Diagrams

Diagram 1: Mechanism of Nanoparticle Stabilization

Mechanism of Nanoparticle Stabilization\ This diagram illustrates the two primary mechanisms to prevent nanoparticle aggregation: creating a physical barrier with a dense PEG layer (steric stabilization) and increasing electrostatic repulsion between particles by modifying surface charge (electrostatic stabilization).

Diagram 2: Elasticity-Circulation Relationship

Elasticity-Circulation Relationship\ This flowchart shows how tuning nanoparticle elasticity to an intermediate range leads to the formation of a specific protein corona, enriched in ApoA1, which in turn promotes a longer systemic circulation lifetime.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Nanoparticle Stability

| Reagent/Material | Function in Stability Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | A "stealth" polymer that provides steric hindrance, reducing protein adsorption and aggregation [1] [2]. | Density and topology (linear vs. cyclic) matter. Cyclic PEG can offer superior stability without chemisorption [2]. |

| Triethoxysilylpropylsuccinic Anhydride (SAS) | A coupling agent that forms a stable, cross-linked siloxane coating on oxide nanoparticles, providing anchor points for PEG [1]. | Creates a robust, hydrophilic base layer for further functionalization. |

| Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1) | A specific plasma protein whose adsorption is correlated with prolonged nanoparticle circulation [4]. | Not a reagent to add, but a biomarker to track. Enrichment on nanoparticles indicates a favorable corona. |

| Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) | A coupling reagent used to covalently link carboxyl groups on nanoparticles to amine-functionalized PEG [1]. | Handle with care; ensures stable amide bond formation. Requires anhydrous conditions. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Used as a blocking agent to passivate nanoparticle surfaces and minimize non-specific binding in assays and in vivo [7]. | A common "dysopsonin" that can help reduce uptake by immune cells [6]. |

Key Biological Barriers to Circulation Longevity

For researchers in drug development, the systemic circulation lifetime of nanoparticles (NPs) is a critical determinant of therapeutic efficacy. A longer circulation time increases the probability of NPs reaching their intended target tissue. However, a complex array of biological barriers actively works to clear these particles from the bloodstream. This guide details the primary biological hurdles and provides evidence-based troubleshooting strategies to overcome them, directly supporting the broader thesis of improving nanoparticle structural stability in circulation research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the most significant biological event that determines nanoparticle circulation time? The formation of a protein corona is arguably the most critical event. Within minutes of entering the bloodstream, nanoparticles are coated by a layer of adsorbed plasma proteins. This corona defines the nanoparticle's "biological identity" to immune cells, overriding its synthetic surface properties. The composition of this corona directly influences opsonization—the process that marks the nanoparticle for clearance by phagocytic cells in the liver and spleen [4].

FAQ 2: How does nanoparticle elasticity influence their physiological fate? Recent evidence demonstrates that nanoparticle elasticity has a non-monotonic relationship with systemic circulation lifetime. This means that neither the softest nor the stiffest particles perform best. Instead, particles with intermediate elasticity (in the range of 75–700 kPa) have been shown to exhibit the longest circulation times. This is because elasticity selectively influences the adsorption of specific plasma proteins, such as apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1), whose presence correlates strongly with prolonged circulation [4].

FAQ 3: Beyond the protein corona, what other aging-related barriers affect circulation? The integrity of the body's physiological barriers, including the endothelium that lines blood vessels, decreases with age. This is due to age-related loss of homeostasis, changes in gene expression, and morphological alterations in cells and tissues [10]. Furthermore, the aging process is associated with chronic, low-grade inflammation ("inflammaging") and immunosenescence (the decline of immune function), which can alter how the body interacts with and clears nanoparticles [11] [12].

FAQ 4: Are there biological factors more important than nanoparticle design? Yes. A large-scale study on aging revealed that lifestyle and environmental factors (e.g., smoking, physical activity, socioeconomic status) have a significantly greater impact on health and mortality than genetic predisposition. This suggests that the patient's overall health and physiological status, which are shaped by these factors, could profoundly influence the performance and distribution of nanomedicines [13].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Rapid Clearance of Nanoparticles from Circulation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Protein Corona-Induced Opsonization. The nanoparticle surface is optimized for stealth but still adsorbs opsonic proteins (e.g., immunoglobulins, complement factors) that promote phagocytosis [4].

- Solution: Re-evaluate surface chemistry and elasticity. A high-density PEGylated surface can selectively suppress the adsorption of certain plasma proteins. Furthermore, tuning nanoparticle elasticity to an intermediate range (e.g., 75-700 kPa) has been shown to promote the enrichment of ApoA1 in the corona, which is associated with longer circulation [4].

Cause: Poor Barrier Integrity in Disease Models. If using an animal model with underlying inflammation or metabolic disease, the vascular endothelium may be more "leaky" or adhesive, facilitating nanoparticle extravasation or immune cell binding.

Problem 2: High Variability in Circulation Longevity Between Batches

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inconsistent Nanoparticle Elasticity. Even with tight control over size and surface charge, batch-to-batch variations in core cross-linking density or material composition can lead to significant differences in elasticity, which in turn alters the protein corona and circulation fate [4].

- Solution: Implement a standardized quantitative measure of nanoparticle elasticity (e.g., Atomic Force Microscopy) as a critical quality control check before in vivo studies. Ensure your synthesis protocol produces particles with consistent mechanical properties.

Problem 3: Failure in Active Targeting

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Protein Corona Masking. The protein corona can sterically shield targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) conjugated to the nanoparticle surface, preventing their interaction with the intended receptor on target cells [4].

- Solution: Design the targeting strategy with the corona in mind. Consider the density and spacer length of the targeting ligands to mitigate masking effects. Pre-forming the corona in vitro with a curated protein mixture is an advanced strategy to create a more predictable biological identity.

Table 1: The Impact of Nanoparticle Elasticity on Physiological Fate

| Elasticity (Young's Modulus) | Core Composition (Example) | Key Corona Protein Observed | Relative Circulation Lifetime | Key Cellular Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 kPa (Soft) | Liposome | Low ApoA1 | Short | High uptake by phagocytes |

| 75 kPa – 700 kPa (Intermediate) | Polyacrylamide Hydrogel | High ApoA1 | Longest | Reduced cellular uptake |

| 760 MPa (Stiff) | PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | Low ApoA1 | Short | High uptake by phagocytes |

Source: Data adapted from [4]. This study used core-shell nanoparticles with an identical PEGylated lipid bilayer shell, isolating elasticity as the sole variable.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Circulation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| DSPE-PEG2000 | A lipid-PEG conjugate used to create a stealth ("steric stabilization") layer on nanoparticle surfaces, reducing protein adsorption and opsonization. | PEG density is critical; too low offers insufficient protection, too high can cause unexpected immune responses. |

| Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1) | Not a reagent, but a key biomarker. Its preferential adsorption on nanoparticles of intermediate elasticity is a strong positive indicator of prolonged circulation. | Monitor ApoA1 presence in the protein corona via techniques like SDS-PAGE or mass spectrometry as a performance marker. |

| Model Nanoparticles (Core-Shell) | Systems with a hydrogel core and lipid shell allow independent tuning of core elasticity and surface chemistry, perfect for mechanistic studies. | Ensures that differences in circulation are due to elasticity and not other physicochemical parameters [4]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolating and Analyzing the Protein Corona

Objective: To characterize the composition of the protein corona formed on nanoparticles after exposure to biological fluids, a key determinant of their biological fate [4].

Methodology:

- Incubation: Incubate a standardized concentration of your purified nanoparticles (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in mouse or human plasma (e.g., 50% v/v in PBS) for a predetermined time (e.g., 0.5 - 60 minutes) at 37°C.

- Isolation: Separate the nanoparticle-protein corona complexes from unbound proteins. This is typically achieved by centrifugation (for large/dense particles) or size-exclusion chromatography for a cleaner separation.

- Washing: Gently wash the pellet or fractions containing the complexes with a mild buffer (e.g., PBS) to remove loosely associated proteins.

- Elution & Denaturation: Dissociate the proteins from the nanoparticle surface using a denaturing buffer (e.g., Laemmli buffer for SDS-PAGE or RIPA buffer for mass spectrometry).

- Analysis:

- SDS-PAGE: For a quick profile of the total protein corona.

- Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): For a comprehensive, quantitative identification of all adsorbed proteins and their relative abundances.

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact of Elasticity In Vivo

Objective: To systematically determine the relationship between nanoparticle elasticity and systemic circulation lifetime.

Methodology:

- Nanoparticle Fabrication: Synthesize a series of core-shell nanoparticles with identical size, surface charge, and surface chemistry (e.g., PEGylated lipid bilayer) but with cores of varying elasticity (e.g., from ~50 kPa to >1 GPa). Core materials can range from soft hydrogels to stiff polymers like PLGA [4].

- Characterization: Confirm that all batches are monodisperse and matched for hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential. Measure core elasticity via Atomic Force Microscopy.

- In Vivo Tracking: Administer the nanoparticles intravenously to animal models (e.g., mice). Collect blood samples at multiple time points post-injection (e.g., 5 min, 30 min, 1h, 2h, 4h, 8h, 24h).

- Quantification: Measure nanoparticle concentration in the blood over time. This can be done by labeling particles with a fluorescent dye (e.g., DiR) and using in vivo imaging systems (IVIS) or by extracting blood and measuring fluorescence with a plate reader. Calculate pharmacokinetic parameters like half-life (t1/2).

Visualizing Key Concepts

Protein Corona Formation and Its Consequences

Experimental Workflow for Circulation Longevity Studies

The Critical Role of Protein Corona in Determining Biological Identity

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

| Problem Description | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpectedly low transfection efficiency with LNPs despite high cellular uptake. | Protein corona-induced rerouting of LNPs to lysosomal degradation, compromising endosomal escape and cargo delivery [14]. | Pre-form a protein corona with specific proteins (e.g., ApoE) to promote desired intracellular trafficking. Optimize LNP surface chemistry to recruit beneficial corona proteins [14]. | Nature Communications (2025) [14] |

| Rapid clearance of nanoparticles by the immune system and short circulation time. | Opsonins (e.g., immunoglobulins, complement proteins) in the hard corona promote recognition and uptake by phagocytic cells [15] [16]. | Employ PEGylation or use surface modifications with zwitterionic groups (e.g., α-glutamyl) to create stealth properties and reduce opsonin adsorption [16]. | Biomedicines (2021) [16] |

| Inconsistent cellular targeting and unpredictable biodistribution. | Dynamic and variable composition of the protein corona, which is highly influenced by the biological medium and NP physicochemical properties [15] [17]. | Use machine learning models to predict the functional composition of the corona based on NP parameters. Standardize incubation conditions (e.g., plasma concentration, time) during pre-coating [18]. | PNAS (2020) [18] |

| Aggregation of nanoparticles in biological fluids (e.g., blood plasma). | Nanoparticle surface is screened by proteins and salts, overcoming electrostatic repulsion and leading to aggregation. This is common with citrate-capped particles [19]. | Use sterically bulky polymeric capping agents (e.g., BPEI, PEG) instead of small molecules (e.g., citrate, tannic acid) to enhance colloidal stability [19]. | nanoComposix (2018) [19] |

| Loss of catalytic or optical activity of functional nanoparticles. | Conformational changes in proteins adsorbed on the corona, or the corona itself shielding the active surface of the nanoparticle [15] [8]. | Design experiments to understand the hard corona composition. Consider engineering the corona to preserve specific active crystal facets or optical properties [15] [8]. | J. Phys. Chem. C (2019) [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between the "hard" and "soft" protein corona, and which one is more critical for determining biological identity?

The hard corona is a tightly bound layer of proteins with high affinity for the nanoparticle surface, characterized by slow exchange rates and relative stability. The soft corona consists of proteins that are loosely bound, often to the hard corona itself, with rapid exchange rates [16]. The hard corona is generally considered more critical as it is more stable and defines the initial identity of the nanoparticle that cells encounter, directly influencing cellular recognition and uptake [16].

Q2: How can I isolate the protein corona from my nanoparticles for analysis, especially for soft nanoparticles like Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)?

Isolating the intact corona from soft nanoparticles is challenging due to their low density and similarity to endogenous biological particles. Standard centrifugation can cause aggregation or disruption [14]. A recommended method is continuous density gradient ultracentrifugation (DGC) with extended centrifugation times (e.g., 16-24 hours). This approach gently separates protein-LNP complexes from denser plasma proteins and endogenous particles based on buoyant density, allowing for a cleaner isolation suitable for downstream mass spectrometry analysis [14].

Q3: Can I prevent protein corona formation altogether to maintain my nanoparticle's synthetic identity?

Completely preventing corona formation is extremely difficult and may not be desirable, as the corona mediates key biological interactions. The primary strategy is to engineer a stealth corona that directs favorable biological outcomes. While PEGylation is the gold standard for reducing opsonization and prolonging circulation, it does not fully prevent corona formation [16]. Advanced strategies, such as conjugating zwitterionic groups (e.g., α-glutamyl) to PEG termini, have shown improved stealth properties and reduced protein adsorption compared to conventional PEG [16].

Q4: How does the protein corona affect the stability of my nanoparticle formulation?

The protein corona can have dual effects on stability. It can prevent aggregation by providing steric stabilization; for instance, BSA adsorption has been shown to prevent the aggregation of iron oxide nanoparticles [15]. Conversely, it can induce aggregation if the adsorbed proteins cause bridging between particles. Furthermore, for certain materials like silver nanoparticles, proteins in the corona can influence the release of ions (e.g., by acting as a silver ion "sink"), thereby altering the nanoparticle's chemical stability and dissolution rate [15] [19].

Q5: Are there computational tools to predict the protein corona composition to guide nanoparticle design?

Yes, traditional linear models perform poorly for this complex task. However, machine learning (ML), particularly Random Forest (RF) models, has emerged as a powerful tool. By integrating meta-analysis of existing data, ML can quantitatively predict the functional composition of the protein corona (e.g., relative abundance of immune proteins, apolipoproteins) based on a nanoparticle's physicochemical properties and experimental conditions with high accuracy (R² > 0.75). This can then be used to predict downstream biological responses like cellular uptake by macrophages [18].

Data Presentation

| Parameter | Influence on Protein Corona | Impact on Biological Identity & Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Thicker corona on larger nanoparticles; influences protein binding capacity [15]. | Affects biodistribution, macrophage uptake, and circulation time. |

| Surface Charge | Positively charged NPs often adsorb more proteins, particularly those with negative charge [15]. | Influences colloidal stability, cellular internalization, and potential cytotoxicity. |

| Surface Chemistry | The most critical factor. Determines affinity for specific protein groups. Hydrophobicity and functional groups (e.g., -COOH, -NH₂) dictate binding [18]. | Directs organ targeting (e.g., ApoE binding for liver targeting), immune response, and blood circulation half-life. |

| Shape | Proteins retain more stable structure on spherical NPs compared to high-curvature nanostructures (e.g., rods) [15]. | Alters interaction with cell membranes and internalization pathways. |

| Incubation Conditions (pH, Time, Temp) | Alters protein conformation and binding kinetics; longer time leads to more stable hard corona [15]. | Defines the maturity and stability of the corona, affecting the reproducibility of in-vivo outcomes. |

| Functional Protein Category | Example Proteins | Common Biological Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Apolipoproteins | ApoE, ApoA-I | Facilitates targeting to specific tissues (e.g., liver via LDL receptor binding); can enhance cellular uptake [15] [14]. |

| Immune Proteins | Immunoglobulins (IgG), Complement Proteins | Acts as opsonins, promoting recognition and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), reducing circulation time [18]. |

| Coagulation Factors | Fibrinogen, Vitronectin | May trigger thrombotic responses or influence adhesion to vascular endothelial cells [14]. |

| Acute Phase Proteins | C-reactive Protein, Alpha-2-Macroglobulin | Modulates inflammatory responses; can either promote or suppress immune cell uptake [14]. |

| "Stealth" Proteins | Clusterin, Serum Albumin | Can confer stealth properties by reducing phagocytosis and increasing circulation time [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

This protocol is designed to minimize co-isolation of endogenous nanoparticles and preserve the integrity of the soft LNP-corona complex.

- LNP Incubation: Inculate your LNP formulation with human blood plasma (or other relevant biofluid) at a physiologically relevant concentration and temperature (e.g., 37°C) for a desired time (e.g., 1 hour) to allow corona formation.

- Gradient Preparation: Prepare a continuous density gradient (e.g., iodixanol gradient) in an ultracentrifuge tube. The density should range to accommodate the buoyant density of LNPs (typically low).

- Sample Loading: Carefully layer the LNP-plasma incubation mixture on top of the pre-formed density gradient.

- Ultracentrifugation: Centrifuge the samples at high speed (e.g., ~100,000 - 200,000 × g) for an extended period (16-24 hours at 4°C). This prolonged run is critical for effective separation from endogenous particles.

- Fraction Collection: After centrifugation, carefully fractionate the gradient from the top. The protein-LNP complexes will band at their buoyant density.

- Corona Characterization:

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the fractions via label-free quantitative mass spectrometry to identify and quantify the proteins in the corona. Normalize to the protein composition in the plasma control alone.

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity of the fractions to confirm LNP size and monodispersity.

- Functional Assays: Use the isolated LNP-corona complexes in downstream cell culture experiments (e.g., uptake, transfection efficiency) to link corona composition to biological function.

This protocol directly tests the functional consequence of the protein corona on mRNA delivery.

- Corona Pre-formation: Create two sets of LNPs:

- Experimental Group: Pre-incubate LNPs with a selected protein (e.g., Vitronectin) or full plasma to form a corona.

- Control Group: Bare LNPs in buffer.

- Cell Treatment: Treat human liver cells (e.g., HepG2) with both groups of LNPs. Use a consistent nanoparticle concentration based on particle number.

- Uptake Measurement: After a few hours, measure cellular uptake using flow cytometry (if LNPs are fluorescently labeled) or other suitable methods.

- Expression Analysis: After 24-48 hours, measure mRNA expression levels using techniques like qRT-PCR or fluorescence microscopy (if the mRNA encodes a reporter protein like GFP).

- Data Interpretation: Correlate uptake data with expression data. A key finding may be that certain corona proteins increase uptake but do not enhance, or even decrease, functional mRNA expression, indicating corona-induced trafficking to degradative pathways rather than productive endosomal escape [14].

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Protein Corona Impact on LNP Transfection

Diagram 2: Machine Learning Prediction of Corona & Bio-Effects

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application in Corona Research |

|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Commonly used model nanoparticles due to their unique optical properties (Surface Plasmon Resonance) which shift upon protein binding, allowing for real-time monitoring of corona formation [15]. |

| PEGylated Lipids | Used in LNP formulations to provide a steric barrier, reducing non-specific protein adsorption and opsonization, thereby prolonging circulation time. A key tool for creating stealth nanoparticles [14] [16]. |

| Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) | A critical functional protein in the corona. Its adsorption onto LNPs is a known mechanism for hepatocyte targeting via the LDL receptor. Used in pre-coating experiments to direct liver-specific delivery [14]. |

| Density Gradient Media (e.g., Iodixanol) | Essential for isolating intact protein-LNP complexes from biological fluids using ultracentrifugation, enabling proteomic analysis of the corona without contamination from endogenous particles [14]. |

| Random Forest Machine Learning Models | A computational tool used to accurately predict the functional composition of the protein corona and subsequent cellular recognition based on nanoparticle parameters, guiding rational NP design before synthesis [18]. |

Impact of Physicochemical Properties on Stability and Fate

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do the core physicochemical properties of a nanoparticle influence its stability in biological fluids?

Answer: The core physicochemical properties of a nanoparticle are fundamental determinants of its stability in circulation. Instability can lead to premature drug release, aggregation, or rapid clearance, undermining therapeutic efficacy. The following properties are critical:

- Size and Surface Charge: Nanoparticles must be designed with a negative surface charge to prevent accelerated blood clearance (ABC), a phenomenon where particles are rapidly cleared from the blood by the kidney and liver [20]. In contrast, a positive surface charge can increase cell affinity and uptake in diseased tissues via the Enhanced Permeation and Retention (EPR) effect, but it must be carefully balanced against circulation time [20].

- Surface Chemistry and Corona Formation: Upon injection into the bloodstream, nanoparticles are rapidly coated by proteins and lipids, forming a "corona". The composition of this corona is dictated by the nanoparticle's original surface chemistry and electrical charge, and it defines the biological identity that the immune system interacts with [20]. This corona can trigger opsonization, leading to phagocytosis and clearance.

- Mechanical Properties (Stiffness): The material composition (e.g., polymeric vs. metallic) determines nanoparticle stiffness. Softer nanoparticles (like lipidic ones) can deform more easily but may have a lower rate of cellular uptake compared to stiffer metal or silica nanoparticles [20].

Table 1: Impact of Key Physicochemical Properties on Stability and Fate

| Property | Impact on Stability & Fate | Consequence of Poor Control |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Determines the pathway and efficiency of cellular uptake (endocytosis) [20]. Influences circulation time and tissue penetration. | Off-target effects; accelerated clearance; reduced cellular internalization. |

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) | Affects particle affinity for cell membranes and protein corona composition [20]. A high zeta potential (positive or negative) prevents aggregation [21]. | Aggregation in suspension; opsonization and rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). |

| Surface Chemistry / Ligands | Directs active targeting to specific cells; can be engineered for "stealth" properties (e.g., using PEG) to evade immune detection [20]. | Non-specific binding; immune recognition; failure to reach the target site. |

| Hydrophobicity | Influences the interaction with biological membranes and serum proteins [20]. | Increased protein adsorption, leading to opsonization and aggregation. |

FAQ 2: My nanoparticle formulation is aggregating in serum. What are the primary causes and solutions?

Answer: Aggregation is a primary indicator of instability and is often caused by particle collisions that overcome repulsive forces [8]. In serum, this is exacerbated by interactions with proteins and ions.

Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Unfavorable Surface Charge. A low zeta potential (near neutral) reduces the electrostatic repulsion between particles, allowing them to agglomerate [21].

- Solution: Modify the surface chemistry to increase the zeta potential. This can be achieved by introducing charged functional groups or using stabilizers that provide steric hindrance [8].

- Cause: High Nanoparticle Concentration. A high particle density increases the collision frequency, raising the probability of aggregation [22].

- Solution: Follow recommended concentration guidelines and use a sonicator to disperse nanoparticles evenly before introduction into biological media [22].

- Cause: Non-Specific Protein Binding. Proteins in serum can bridge between nanoparticles, causing them to clump together [20].

- Solution: Incorporate stabilizing agents like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or use blocking agents such as Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) after conjugation to shield the surface from non-specific interactions [22].

FAQ 3: What advanced analytical techniques can I use to quantitatively monitor nanoparticle stability in complex biological media like plasma?

Answer: Conventional dynamic light scattering (DLS) can be unreliable in biological fluids due to interference from plasma proteins and other components [23]. More sophisticated techniques are required for accurate analysis.

Recommended Technique: Size-Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS)

- Methodology: This technique separates nanoparticles from biological matrix components (like free proteins) before analysis. The dual-angle light scattering detector then provides absolute measurements of molecular weight and radius of gyration without relying on column calibration standards [23].

- Application: SEC-MALS can elucidate degradation kinetics and physical property changes of nanoparticles in pure human serum and plasma. For instance, it has been used to discover that even a trace impurity (~1%) in a lipid component (ALC-0315) can greatly diminish mRNA-LNP stability in serum [23].

- Protocol Outline:

- Sample Preparation: Incubate your nanoparticle formulation (e.g., mRNA-LNPs) in human plasma or serum for designated time points.

- Chromatographic Separation: Use a dual-column configuration to attenuate interference from plasma components.

- On-line Detection: Pass the eluent through a MALS detector and a refractive index (RI) detector.

- Data Analysis: Software calculates the absolute molar mass and size of the nanoparticles in the solution, allowing you to track changes in integrity over time [23].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental protocol for analyzing nanoparticle stability using SEC-MALS:

FAQ 4: How does the "protein corona" form and how does it alter the intended fate of nanoparticles in the body?

Answer: The protein corona is a dynamic layer of biomolecules that adsorbs spontaneously onto a nanoparticle's surface upon contact with biological fluids [20]. This process fundamentally alters the nanoparticle's biological identity.

- Formation Mechanism: The formation is driven by the physicochemical properties of the nanoparticle, including its surface chemistry, electrical charge, and hydrophobicity [20]. The Vroman effect describes the competitive and time-dependent exchange of proteins on the surface, where proteins with high abundance and mobility adsorb first, and are later replaced by proteins with higher affinity.

- Impact on Fate:

- Altered Cellular Recognition: The corona, not the synthetic nanoparticle surface, is what cells "see." It can mask targeting ligands, rendering them ineffective, or create new, unintended biological interactions.

- Shift in Pharmacokinetics: A corona rich in opsonins (proteins that mark particles for phagocytosis) leads to rapid clearance by macrophages in the liver and spleen. Conversely, a corona rich in "dysopsonins" (like albumin) can promote longer circulation times [20].

- Changed Biodistribution: The ultimate destination of the nanoparticle in the body is largely dictated by the composition of the hard protein corona that forms within the first few minutes of entering circulation.

FAQ 5: What are the critical steps for conjugating biomolecules to nanoparticles without compromising stability?

Answer: Successful conjugation requires optimizing reaction conditions to maintain nanoparticle dispersion and biomolecule activity.

- Optimize pH: The pH of the conjugation buffer significantly impacts binding efficiency. For example, antibody conjugation to gold nanoparticles typically works best at a pH near or slightly above the isoelectric point of the antibody, often around pH 7-8 [22].

- Prevent Aggregation: Adjust the concentration of nanoparticles to prevent crowding and aggregation during the reaction. Sonication prior to conjugation is recommended [22].

- Determine Optimal Ratio: An inadequate or excessive amount of antibody (or other biomolecule) can hinder conjugation efficiency and lead to unbound particles that disrupt assays. Use precise ratios as suggested in conjugation kits or determined empirically [22].

- Use Stabilizers: After conjugation, incorporate stabilizing agents like BSA or PEG to enhance shelf life and prevent non-specific binding in diagnostic applications [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Nanoparticle Stability and Fate Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A "stealth" polymer conjugated to nanoparticle surfaces to reduce protein adsorption (opsonization) and prolong circulation time [20]. | PEG density and chain length are critical for creating an effective hydration barrier. |

| HEPES or Phosphate Buffers | Provide a stable pH environment for conjugation reactions and stability studies [22]. | Buffer capacity and ionic strength must be optimized to prevent nanoparticle aggregation. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used as a blocking agent to passivate nanoparticle surfaces and prevent non-specific binding in assays and in vivo [22]. | High-purity grades are essential to avoid introducing contaminants. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | For purifying conjugated nanoparticles from unreacted reagents and for analyzing stability in complex media via SEC-MALS [23]. | Column pore size must be selected to match the hydrodynamic size of the nanoparticle. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Polymers (e.g., pH-sensitive) | Used to design "smart" nanoparticles that release their cargo in response to specific biological stimuli (e.g., low tumor pH) [20]. | The trigger mechanism (pH, ROS, enzyme) must be highly specific to the target microenvironment. |

| HEPA-Filtered Local Exhaust Ventilation | An engineering control (e.g., fume hood, glove box) to protect researchers from inhaling airborne nanoparticles during synthesis and handling [24] [25]. | Required when handling dry powder nanomaterials to minimize inhalation exposure risk. |

For researchers in drug development, the journey of an intravenously injected nanoparticle is a race against time and the body's sophisticated defense systems. The therapeutic promise of nanocarriers—spatial and temporal controlled drug delivery—is often compromised by their rapid destabilization and clearance from the bloodstream [26] [27]. Achieving successful delivery requires navigating a series of biological barriers, where processes like aggregation, opsonization, and phagocytic clearance can prematurely eliminate nanoparticles before reaching their target site [26]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting methodologies to diagnose and overcome these destabilization mechanisms, framed within the thesis that rational design and precise characterization are paramount for improving nanoparticle structural stability in systemic circulation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Key Issues and Solutions

FAQ 1: My nanoparticle formulations are aggregating in biological media. How can I prevent this?

- Problem: Nanoparticles aggregate when introduced into blood serum or plasma, leading to increased particle size, potential capillary blockade, and altered biodistribution.

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Verify Concentration: Aggregation often occurs when nanoparticle concentration is too high. Follow recommended concentration guidelines and use sonication to disperse particles evenly before use [28].

- Optimize Surface Chemistry: Incorporate steric stabilizers. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) is the gold-standard for creating a hydrophilic, steric barrier that reduces interparticle attraction and aggregation [26] [27]. A common practice is to use PEG-conjugated lipids (e.g., DSPE-PEG2000) in the nanoparticle shell [4].

- Employ Blocking Agents: After synthesis and conjugation, use blocking agents like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or casein to coat the surface and minimize non-specific interactions that lead to aggregation [28] [29].

FAQ 2: My nanoparticles are being cleared from the blood circulation too quickly. What is the mechanism and how can I extend their circulation lifetime?

- Problem: Rapid clearance of nanoparticles, primarily by the Mononuclear Phonuclear Phagocytic System (MPS), limits their ability to reach the target tissue.

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Understand Opsonization: The primary mechanism for rapid clearance is opsonization, where blood serum proteins (opsonins) adsorb to the nanoparticle surface, tagging them for phagocytosis [26] [27]. Common opsonins include immunoglobulins, complement proteins (C3, C4, C5), albumin, and apolipoproteins [26].

- Implement "Stealth" Coating: The most effective strategy is PEGylation—grafting, entrapping, or adsorbing PEG chains onto the nanoparticle surface. This creates a steric shield that reduces opsonin protein adsorption and MPS recognition, significantly prolonging circulation half-life [27].

- Consider Nanoparticle Elasticity: Recent evidence indicates that nanoparticle elasticity non-monotonically affects systemic circulation lifetime, correlating with the composition of the protein corona. Tuning elasticity (e.g., to an intermediate range of 75–700 kPa) can promote the adsorption of specific proteins like Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1), which is strongly correlated with longer blood circulation times [4].

FAQ 3: I am getting inconsistent results in my diagnostic assay. Could nanoparticle conjugation be the issue?

- Problem: Inconsistent signal, high background, or false positives in nanoparticle-based diagnostics (e.g., lateral flow assays, ELISA).

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Check Conjugation Buffer pH: The pH of the conjugation buffer significantly impacts biomolecule binding efficiency. For antibody conjugations with gold nanoparticles, a pH around 7-8 is generally optimal. Use dedicated conjugation buffers to maintain stable pH and molecule integrity [28].

- Optimize Antibody-to-Nanoparticle Ratio: Inadequate or excessive antibody amounts can hinder conjugation efficiency and assay performance. Use precise ratio suggestions provided by kit manufacturers or determine the optimal ratio empirically [28].

- Prevent Non-Specific Binding: Use blocking agents like BSA or PEG in the assay incubation steps to prevent nanoparticles from attaching to unintended molecules, which causes high background and false positives [28] [29].

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

Protocol 1: Analyzing Protein Corona Composition

Objective: To isolate and identify proteins adsorbed onto nanoparticles after incubation in plasma, providing insight into opsonization potential.

Materials: Nanoparticle sample, mouse or human plasma, ultracentrifuge, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) system, mass spectrometry.

Method:

- Incubation: Incubate your nanoparticle sample (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in plasma (e.g., 50% v/v in PBS) for a predetermined time (e.g., 1 hour) at 37°C [4].

- Isolation of Corona-Coated Nanoparticles: Ultracentrifuge the mixture (e.g., at 100,000 × g for 1 hour) to pellet the nanoparticles with their hard protein corona.

- Washing: Carefully remove the supernatant and gently wash the pellet with PBS to remove loosely associated proteins. Repeat centrifugation.

- Protein Elution & Analysis: Re-suspend the pellet in SDS-PAGE loading buffer to elute the corona proteins. Analyze via:

- SDS-PAGE: For a gross profile of corona proteins.

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): For precise identification of individual corona proteins, such as ApoA1, whose abundance can be correlated with circulation lifetime [4].

Protocol 2: Evaluating In Vivo Circulation Lifetime

Objective: To quantitatively measure the pharmacokinetic profile and blood circulation half-life of nanoparticles.

Materials: Fluorescently or radio-labeled nanoparticles, animal model (e.g., mouse), IV injection setup, blood collection equipment, fluorescence spectrometer or gamma counter.

Method:

- Dosing: Intravenously inject a known dose of labeled nanoparticles into the animal model (e.g., via tail vein).

- Serial Blood Sampling: Collect small blood samples (e.g., 10-20 µL) from the retro-orbital plexus or tail vein at multiple time points post-injection (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours).

- Processing: Lyse the blood samples and isolate the plasma fraction by centrifugation.

- Quantification: Measure the signal (fluorescence or radioactivity) in each plasma sample and compare it to a standard curve of the injected formulation.

- Pharmacokinetic Analysis: Plot nanoparticle concentration in blood versus time. Calculate key parameters like circulation half-life (t1/2) and area under the curve (AUC) to compare the performance of different formulations [4] [27].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Relationships

Table 1: Impact of Nanoparticle Physicochemical Properties on Stability and Clearance

| Property | Effect on Aggregation | Effect on Opsonization | Impact on Circulation Lifetime |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Larger particles (>200 nm) are more prone to sedimentation and aggregation. | Optimal size for avoiding MPS is reported to be 10-100 nm [26]. | Smaller sizes (within optimal range) generally show longer circulation [26]. |

| Surface Charge | Highly charged surfaces (positive or negative) can cause electrostatic aggregation in high-salt media. | Neutral or slightly negative surfaces tend to reduce opsonin adsorption [26] [27]. | Neutral, "stealth" surfaces significantly prolong half-life compared to charged ones [27]. |

| Surface Chemistry (PEGylation) | Reduces aggregation by steric hindrance. | Dramatically reduces opsonization by forming a hydrophilic shield [27]. | Can increase circulation half-life from minutes to hours or days [27]. |

| Elasticity | Softer particles may be more prone to deformation and fusion under stress. | Non-monotonically affects protein corona composition; intermediate elasticity (75-700 kPa) enriches for ApoA1 [4]. | Shows a non-monotonic relationship; maximum lifetime correlated with intermediate elasticity and high ApoA1 adsorption [4]. |

Table 2: Key Opsonins and Their Roles in Nanoparticle Clearance

| Opsonin | Function in Clearance | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM) | Bind to foreign surfaces and engage Fc receptors on macrophages. | Major initiators of phagocytosis [27]. |

| Complement Proteins (C3, C4, C5) | Form "membrane attack complex" and tag particles for phagocytosis. | A key part of the innate immune response to nanoparticles [27]. |

| Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1) | Main protein component of HDL. | Recent studies show its enrichment in the corona is strongly correlated with longer systemic circulation lifetime [4]. |

| Fibrinogen | Acute phase protein; adsorption can trigger inflammatory responses. | High adsorption may lead to platelet aggregation and immune activation [26]. |

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram: Protein Corona Formation and MPS Clearance

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Stability Testing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Nanoparticle Stabilization and Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| DSPE-PEG2000 | A PEG-conjugated lipid used to create a sterically stabilizing "stealth" coating on lipid and polymeric nanoparticles. | PEG density and chain length are critical for effective protein repulsion [4] [27]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Used as a blocking agent to passivate surfaces and minimize non-specific binding in assays and formulations. | Can be chemically modified (e.g., BSA-c) to better overcome charge-based interactions [29]. |

| Poloxamers/Poloxamines (e.g., Pluronic F127, Poloxamine 908) | Non-ionic surfactants that can be adsorbed onto nanoparticles to reduce opsonization and MPS uptake. | An alternative to PEGylation; their effectiveness depends on the copolymer chain arrangement [27]. |

| Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (TRPS) | A high-resolution, single-particle technique for characterizing size, concentration, and zeta potential. | Crucial for accurately analyzing polydisperse samples and detecting nanoparticle subpopulations that may aggregate [30]. |

| Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1) | A specific plasma protein whose corona abundance is a potential biomarker for predicting nanoparticle circulation time. | Enrichment in the protein corona on nanoparticles of intermediate elasticity correlates with longer circulation [4]. |

Engineering Stable Nanoparticles: Design Strategies and Advanced Materials

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary mechanism by which PEGylation confers "stealth" properties to nanoparticles?

PEGylation creates a hydrophilic, steric barrier around the nanoparticle that reduces nonspecific interactions with blood components. The flexible PEG chains form a hydrated shield through hydrogen bonding with water molecules. This shield minimizes opsonization—the adsorption of proteins that mark particles for clearance by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS)—thereby prolonging circulation time. The stealth effect is influenced by PEG conformation, which transitions from a "mushroom" state at low density to an extended "brush" state at high surface density, with the latter providing more effective shielding [31] [32].

FAQ 2: What is the "PEG Dilemma," and how does it impact drug delivery efficacy?

The "PEG Dilemma" refers to the paradoxical challenge where the same PEG coating that provides beneficial stealth properties can also create a physical barrier that hinders the cellular uptake of nanoparticles by the target cells. This steric hindrance can prevent the nanoparticle from interacting with cellular receptors, thereby reducing the internalization and efficacy of the delivered therapeutic, especially for agents that require intracellular activity (e.g., DNA, RNA, certain chemotherapeutics) [33] [34]. Furthermore, PEG can trigger immune responses, such as the production of anti-PEG antibodies, which exacerbate this problem by accelerating blood clearance upon repeated administration [34] [35].

FAQ 3: What are the key structural parameters of PEG that influence nanoparticle performance?

The immunological safety and performance of PEGylated nanoparticles are highly dependent on several structural parameters of the PEG-lipid conjugate [35]:

- PEG Chain Length: Has a biphasic effect; both very short and very long chains are more likely to induce the Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) phenomenon.

- PEG Density (Surface Coverage): Also exhibits a biphasic effect, where both very low and very high densities can impact stealth properties and immunogenicity.

- PEG Architecture: Branched PEG conjugates often confer superior stealth properties compared to linear PEGs.

- Terminal Functional Group: The chemical group at the end of the PEG chain (e.g., methoxy, carboxyl, amine) can significantly impact immunogenicity and clearance rate.

- Lipid Anchor Structure: The hydrophobicity and length of the lipid moiety (e.g., DSPE, ceramide) anchoring the PEG to the nanoparticle influence stability and pharmacokinetics.

FAQ 4: What are the main alternatives being explored to overcome the limitations of traditional PEGylation?

Researchers are developing advanced strategies to move beyond the limitations of conventional PEG coatings [33] [35] [32]:

- Sheddable PEG Coatings: PEG is attached via linkers that are cleaved in response to specific stimuli in the tumor microenvironment (TME), such as low pH or overexpressed enzymes (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases). This allows the particle to shed its stealth coat upon reaching the target, facilitating cellular uptake.

- Alternative Polymers: Hydrophilic polymers like poly(oxazoline) (POZ), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and poly(glycerol) are being investigated as potential replacements for PEG to avoid anti-PEG immune responses.

- Zwitterionic Coatings: Materials that possess both positive and negative charges, creating a super-hydrophilic surface that resists protein adsorption effectively.

- Biomimetic Coatings: Using natural cell membranes (e.g., from red blood cells or leukocytes) to cloak nanoparticles, providing innate biocompatibility and active targeting capabilities [36].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Reduced Cellular Uptake of PEGylated Nanoparticles

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High efficacy in vitro but low efficacy in vivo. | Steric hindrance from PEG shield preventing interaction with target cell receptors [34]. | Implement a sheddable PEG strategy. Use a pH-sensitive (e.g., hydrazone bond) or enzyme-cleavable (e.g., MMP-2 sensitive peptide linker) covalent bond between the PEG and nanoparticle core [33]. |

| Confirmed long circulation half-life but poor tumor regression. | The PEG coating remains intact, creating a barrier to cellular internalization. | Optimize PEG surface density. A lower density might reduce steric hindrance while maintaining sufficient stealth properties; however, balance is key to avoid opsonization [31]. |

| Poor transfection (for gene delivery) despite good tumor accumulation. | PEG interferes with intracellular processes post-internalization [34]. | Functionalize PEG terminal groups with targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies) to promote receptor-mediated endocytosis, overcoming the non-specific blocking effect [33] [37]. |

Challenge 2: Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC Phenomenon) Upon Repeated Dosing

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| First dose shows prolonged circulation, but second dose is rapidly cleared. | Anti-PEG IgM antibodies produced after the first dose bind to the second dose, promoting opsonization and clearance by macrophages in the liver and spleen [34] [35]. | Adjust the injection schedule. The ABC phenomenon is most pronounced with dosing intervals of 3-7 days and attenuates by 4 weeks [34]. |

| Reduced Area Under the Curve (AUC) for subsequent doses. | The ABC phenomenon has an inverse relationship with the first dose quantity; very low first doses optimally induce anti-PEG IgM [34]. | Use a high first dose (e.g., 5 µmol/kg) to induce B-cell anergy or tolerance, reducing the anti-PEG antibody response [34]. |

| Increased hepatic and splenic accumulation of the second dose. | Anti-PEG antibodies trigger complement activation and Fc-receptor-mediated phagocytosis. | Modify PEG structure. Utilize branched PEG architectures or carefully optimize PEG chain length and density to make the coating less immunogenic [38] [35]. |

Challenge 3: Complement Activation-Related Pseudoallergy (CARPA)

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Acute hypersensitivity reactions (e.g., skin flushing, hypotension) in animal models or patients shortly after infusion. | PEGylated nanoparticles activating the complement system, leading to the release of anaphylatoxins (C3a, C5a) [35] [32]. | Pre-medicate with corticosteroids and antihistamines to mitigate inflammatory reactions. |

| Batch-to-batch variability in reaction severity. | Factors like PEG surface density, conjugation chemistry, and nanoparticle charge influence complement activation [32]. | Control nanoparticle surface charge. Avoid highly negative or positive charges. A near-neutral zeta potential is generally desired for stealth properties [31]. |

| Reactions occur even with low levels of anti-PEG antibodies. | Activation can occur via the lectin pathway or alternative pathway, independent of antibodies, especially with high molecular weight PEGs [32]. | Consider alternative stealth polymers like POZ or PVA for new formulations if PEG-specific issues persist [35]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating the Protein Corona and Opsonization

Objective: To analyze the profile of serum proteins that adsorb onto PEGylated nanoparticles, which defines their biological identity and fate.

Materials:

- Purified PEGylated nanoparticle formulation (and non-PEGylated control)

- Complete cell culture medium supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) or human plasma

- Ultracentrifuge

- SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis system

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) equipment

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Zeta Potential instruments

Methodology:

- Incubation: Incubate a standardized concentration of nanoparticles (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in 50% FBS or human plasma at 37°C for 1 hour to simulate in vivo conditions [33].

- Isolation of Corona-Coated NPs: Separate the nanoparticles from unbound proteins by ultracentrifugation (e.g., 100,000 g for 1 hour). Gently wash the pellet with PBS to remove loosely associated proteins.

- Protein Elution: Resuspend the nanoparticle pellet in a strong denaturing buffer (e.g., Laemmli buffer) to elute the hard corona proteins.

- Analysis:

- SDS-PAGE: Run the eluted proteins on a gel to visualize and compare the total protein amount and pattern between PEGylated and non-PEGylated formulations [34].

- Mass Spectrometry: Identify the specific proteins present in the corona to understand which opsonins or dysopsonins are adsorbed [33].

- DLS/Zeta Potential: Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and surface charge of the nanoparticles before and after corona formation. A significant change indicates substantial protein adsorption [37].

Protocol 2: Assessing Cellular Uptake In Vitro

Objective: To quantify and visualize the internalization of nanoparticles into target cells, evaluating the impact of PEGylation.

Materials:

- Fluorescently labeled PEGylated and non-PEGylated nanoparticles

- Target cell line (e.g., HeLa, MCF-7)

- Cell culture plates and standard media

- Flow Cytometer

- Confocal Microscope

- Inhibitors (e.g., chloroquine for endocytosis inhibition)

Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in multi-well plates (e.g., 24-well for flow cytometry, glass-bottom dishes for microscopy) and culture until 70-80% confluency.

- Dosing: Treat cells with a consistent concentration of fluorescent nanoparticles in serum-containing media. Include wells for negative controls (no nanoparticles) and pharmacological inhibitors if studying uptake mechanisms.

- Incubation: Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 2-4 hours) at 37°C.

- Washing: Thoroughly wash cells with PBS to remove non-internalized nanoparticles.

- Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: Trypsinize and resuspend cells in PBS. Analyze the fluorescence intensity of the cell population using a flow cytometer. A rightward shift in fluorescence indicates nanoparticle uptake. Compare PEGylated and non-PEGylated formulations [34].

- Confocal Microscopy: Fix cells (e.g., with 4% PFA), stain actin cytoskeleton (e.g., phalloidin) and nuclei (e.g., DAPI). Use a confocal microscope to obtain z-stack images and confirm intracellular localization of nanoparticles versus surface binding [37].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

PEGylated Nanoparticle Journey and Clearance Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Protein Corona Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Heterobifunctional PEG Linkers (e.g., MAL-PEG-NHS) | Enable site-specific, covalent conjugation of PEG to nanoparticles or proteins. The different terminal groups (e.g., Maleimide, NHS Ester) react with specific residues (thiols, amines) [39]. | Crucial for controlling PEG orientation and density. Choice of linker determines conjugation chemistry and stability. |

| PEG-DSPE (Distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine) | A common PEG-lipid conjugate used for post-insertion or co-formulation into lipid nanoparticles and liposomes. The DSPE anchor provides stable incorporation into lipid bilayers [35] [31]. | A workhorse for creating stealth liposomal formulations. The length of the PEG chain and the lipid anchor affect stability and pharmacokinetics. |

| Acid-Labile Linkers (e.g., hydrazone, vinyl ether) | Used to create sheddable PEG coatings. Stable at neutral blood pH but cleave rapidly in the acidic environment of endosomes/lysosomes (pH ~5.0), facilitating intracellular drug release [33]. | Key for resolving the "PEG dilemma". Enables the design of stimuli-responsive nanoparticles that shed PEG upon cellular internalization. |

| Aminosilanes (e.g., APTES) | Used as crosslinkers for the surface functionalization of inorganic nanoparticles (e.g., silica, metal oxides). Introduce primary amine groups for subsequent bioconjugation with activated PEG [37]. | Essential for creating a stable functional layer on specific nanomaterial surfaces as a first step towards PEGylation. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) / Zeta Potential Analyzer | Instruments to characterize the core physicochemical properties of nanoparticles: hydrodynamic size, size distribution (PDI), and surface charge (Zeta Potential) before and after PEGylation [37]. | Mandatory for quality control. Confirms successful PEGylation (often a slight size increase, shift towards neutral zeta potential) and colloidal stability. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most critical factors for ensuring the structural stability of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles (CMCNPs) in circulation?

The structural stability of CMCNPs is governed by a combination of core design, membrane integrity, and surface properties. Key factors include:

- Nanoparticle Core Elasticity: The stiffness of the core material significantly impacts circulation time. Studies using core-shell nanoparticles with identical PEGylated lipid shells but cores of different elasticity (45 kPa to 760 MPa) have revealed a non-monotonic relationship. Nanoparticles with intermediate elasticity (75–700 kPa) demonstrated the longest systemic circulation lifetime, which was strongly correlated with the specific composition of the adsorbed protein corona [4].

- Membrane Protein Integrity and Retention: The functionality of the coating relies on preserving the natural proteins and lipids from the source cell membrane during extraction and fusion. The extraction method (e.g., hypotonic lysis, sonication) and purification process (e.g., differential centrifugation) are critical to maintaining a intact membrane structure with full biological function [40] [41].

- Protein Corona Formation: Upon entering the bloodstream, nanoparticles are rapidly coated by plasma proteins, creating a "biological identity." The elasticity and surface chemistry of the nanoparticle determine the composition of this corona. For instance, a higher relative abundance of apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1) in the corona is strongly correlated with an extended circulation lifetime [4] [42].

FAQ 2: How can I troubleshoot poor targeting efficiency of my biomimetic nanoparticles in vivo?

Poor targeting often stems from issues with margination, adhesion, or off-target clearance.

- Margination: This is the process of particles moving from the center of blood flow to the vessel wall. The "4S" parameters are crucial:

- Size: Larger nanoparticles (e.g., >100 nm) marginate more efficiently than smaller ones [43].

- Shape: Non-spherical particles with higher aspect ratios marginate more quickly than spherical ones [43].

- Stiffness: Stiffer particles tend to marginate better than soft, highly deformable ones [43].

- Surface Functionalization: A stealth coating like PEG can reduce non-specific interactions and prolong circulation, allowing more time for margination to occur [43] [4].

- Cellular Uptake by Immune Cells: If your nanoparticles are being cleared by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) before reaching the target, consider the source of your cell membrane. For example, red blood cell (RBC) membranes are excellent for immune evasion due to CD47 proteins that signal "don't-eat-me," while macrophage membranes possess inherent tropism to inflammatory sites [40] [41].

FAQ 3: My biomimetic nanoparticles are aggregating during synthesis or storage. What are the probable causes and solutions?

Aggregation can be addressed by optimizing the synthesis conditions and characterizing colloidal stability.

- Cause: Incorrect Zeta Potential. A low zeta potential (typically between -10 mV and +10 mV) indicates insufficient electrostatic repulsion between particles, leading to aggregation.

- Solution: Aim for a high zeta potential, either highly positive or highly negative. For example, a chitosan-based nanosystem with a zeta potential of +73 mV demonstrated excellent stability, facilitating efficient interaction with negatively charged cell membranes [44].

- Cause: Membrane Fusion Process. The process of coating the synthetic core with the cell membrane vesicle must be controlled.

- Solution: Use optimized fusion methods like extrusion or sonication. Ensure the size of the core nanoparticle and the cell membrane vesicle are compatible for a uniform coating. Always characterize the final product's hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) using dynamic light scattering; a PDI below 0.3 is generally considered acceptable for a monodisperse population [40] [41].

FAQ 4: Are there methods to actively control the delivery and release of payloads from these nanoparticles?

Yes, beyond passive targeting, bio-inspired designs can incorporate active triggering mechanisms.

- Stimuli-Responsive Cores: Use polymer cores that degrade in response to specific stimuli in the target microenvironment. Common triggers include:

- External Triggers: Incorporate functional materials that respond to external fields.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Short Circulation Half-Life and Rapid Clearance

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Key Experimental Check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticles rapidly disappear from bloodstream in animal models. | Insufficient stealth properties; recognition by immune system. | Use RBC membrane or platelet membrane coating; increase PEG density on surface. | Analyze protein corona composition via SDS-PAGE; check for ApoA1 enrichment [4]. |

| Suboptimal elasticity; too stiff or too soft. | Tune core material (e.g., hydrogel cross-linking density) to achieve intermediate elasticity (~75-700 kPa) [4]. | Use atomic force microscopy (AFM) to measure nanoparticle stiffness. | |

| Incomplete cell membrane coating; exposed synthetic core. | Optimize membrane fusion protocol (e.g., extrusion pressure, sonication time). | Verify coating via Cryo-EM/TEM to visualize core-shell structure [4]. |

Issue 2: Low Targeting Specificity and Accumulation at Disease Site

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Key Experimental Check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low signal/load at target site despite long circulation. | Poor margination in blood flow. | Adjust the "4S" parameters: increase size, use non-spherical shapes, increase stiffness [43]. | Use microfluidic devices with blood flow to observe margination behavior in vitro [42]. |

| Loss of targeting membrane protein function during coating process. | Use gentler extraction methods (e.g., hypotonic lysis); avoid harsh detergents. | Confirm retention of key proteins (e.g., CD47) via Western blot or flow cytometry [40] [41]. | |

| Protein corona masking targeting ligands. | Consider "self" markers from cell membranes that are less masked. | Perform cell binding assays after pre-incubation in plasma to simulate corona formation [4]. |

Issue 3: Inconsistent Batch-to-Batch Performance

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Key Experimental Check |

|---|---|---|---|

| High variability in size, coating efficiency, or in vivo results. | Lack of standardized protocol for membrane extraction and fusion. | Strictly control cell source, lysis conditions, and purification steps (e.g., differential centrifugation) [41]. | Characterize each batch of membrane vesicles for size and protein content before fusion. |

| High polydispersity of final CMCNP product. | Optimize and control the extrusion process; use filters with defined pore sizes. | Measure hydrodynamic diameter and PDI via DLS; aim for PDI <0.3 [44]. | |

| Instability during storage. | Lyophilize with appropriate cryoprotectants (e.g., sucrose, trehalose) and store at -80°C. | Monitor size and zeta potential after reconstitution and over time. |

Quantitative Data for Biomimetic Nanoparticle Design

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Properties and Their Target Ranges for Circulation Stability

| Parameter | Optimal Range for Circulation | Impact on Fate | Characterization Technique | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | 100 - 150 nm | Avoids renal clearance; enhances margination [43]. | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | ||||

| Zeta Potential | > | +20 | mV or <-20 | mV | Prevents aggregation; influences protein corona [44]. | Zetasizer | |

| Elasticity (Young's Modulus) | 75 - 700 kPa | Maximizes circulation lifetime; influences protein corona (e.g., ApoA1) [4]. | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | ||||

| PEG Density | 5 - 10 mol% | Reduces opsonization and MPS uptake [4]. | NMR Spectroscopy, Colorimetric assays | ||||

| Membrane Protein Retention | >80% (vs. source cell) | Preserves biological targeting and "self" signaling [41]. | Western Blot, Flow Cytometry |

Table 2: Comparison of Cell Membrane Sources for Camouflage

| Membrane Source | Key Advantages | Potential Challenges | Ideal Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red Blood Cell (RBC) | Long circulation (CD47-mediated); simple isolation [40] [41]. | Lacks active targeting ligands. | Long-circulating "stealth" platforms; oxygen delivery. |

| Platelet (PLT) | Natural affinity to damaged vasculature and pathogens [40]. | Risk of initiating thrombotic events. | Targeted delivery to sites of vascular injury (e.g., atherosclerosis). |

| Macrophage | Innate tropism to inflammatory and tumor sites [40] [41]. | May be actively recruited to off-target inflamed tissues. | Therapy for inflammatory diseases, cancer. |

| Stem Cell (e.g., MSC) | Homing to injury and tumor sites; secretes reparative factors [40]. | Complex cell culture; risk of ectopic tissue formation (for whole cells, not membranes). | Regenerative medicine; myocardial infarction. |